Section 6: Building Inclusive School Cultures and Policies

International Schools Fostering or Hindering Equal Educational Opportunities

Baran Yousefi; Kristina Pennell-Götze; and Linjie Zhang

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“The Peace School”

“The concept of The Peace School originated in 2005 in Iran as an innovative and alternative approach to education. Despite its progressive vision, the school faced significant challenges, as neither the government nor other organisations supported or approved of its methodology. Consequently, students graduating from the school were left without official diplomas and had to take mainstream assessment tests independently. After 19 years of suppressed operations in Iran, without national or international support or a platform for a voice, a new branch of The Peace School began operating in Toronto, Canada, in 2024 as a private, international elementary school.

The primary goal of establishing this new branch was to support Iranian students by providing them with recognised diplomas for their continued studies. The Peace School is a hub for international students, offering a unique environment where students from diverse backgrounds can learn, share experiences, and influence one another. The school’s philosophy centres on a humanistic, child-centred approach, anticipating that students will be motivated to learn beyond mainstream educational requirements.

Collaboration in decision-making and lesson planning is emphasised, involving families, students, and teachers to create a supportive learning environment. We believe unilateral decisions by any single group — students, parents, or teachers/staff — can compromise education. Regular communication among all parties helps tailor personalised curricula that cater to each child’s unique needs, abilities, and interests. We focus on sparking curiosity and creativity through project-based learning rather than a linear, textbook-driven approach. Instead of conventional numerical grading, we employ a descriptive evaluation process to assess a child’s progress. This holistic approach comprehensively explains each child’s growth and development.

We believe peace is not merely the absence of war; it encompasses principles such as love, empathy, and compassion, which must be learnt during childhood. Our vision is to create a community of positive, optimistic citizens equipped to make transformative impacts on their own lives, the lives of others, and society as a whole. We aim to nurture children who are aware of and engaged with the world, capable of addressing obstacles with innovative solutions, and can contribute meaningfully to a more compassionate and equitable global community.”

Initial questions

- International schools are microcosms of society. What are some of the gaps that exist within international schools?

- Diversity is the core of international schools. How can international schools effectively integrate diversity, equitable practices and foster inclusion?

- Students are agents for change. How can international schools empower students to better foster diversity, equity and inclusion?

Introduction to Topic

In this chapter, we focus on international schools and how they foster or hinder diversity, equity and inclusion. Through examining international schools as microcosms of society, clearly gaps exist within some international school ecosystems. What are the cultural, economic and social gaps? In addition, diversity is a core strength of international schools, so how can diversity, equity and inclusion be fostered? Finally, with an understanding that students are agents for change, how can international schools empower students to better foster diversity, equity, and inclusion as they develop as global citizens?

In an increasingly globalised world (Bittencourt & Willetts, 2018), the international education industry continues to develop and expand in countries around the world (Bunnell et al., 2017; Hayden & Thompson, 2015). Highly influenced by colonialism (Poole & Bunnell, 2021), neoliberalism (Robertson, 2003) and capitalism (Rojo & Percio, 2020), international schools historically cater to the elite social class (Silva-Enos et al., 2022), typically populations of international expatriates from diplomatic, missionary, military, and multinational business organisations (MacDonald, 2009). Over time this has increasingly shifted to include a higher proportion of local host nation upper-middle class children and their families (Hayden, 2011; MacDonald, 2009). However the purpose of international schools has largely remained the same on paper, which is to educate and develop individuals who were socially competent and accepting of political differences, while also highlighting the human rights of all people (UNESCO, 1974).

Some researchers began noticing differences and developed three distinct definitions for the types of international schools that exist (Thompson & Hayden, 2013). These are described below.

The definitions of international school types

“‘Type A’ ‘traditional’ international schools: established principally to cater for globally mobile expatriate families for whom the local education system is not considered appropriate” (Thompson & Hayden, 2013: 5).

‘Type A’ example: The first documented international school is the International School of Geneva (Ecolint), founded in 1924 by visionaries and officials of the League of Nations and International Labour Organisation (Ecolint, 2024). It was founded to cater for children of expatriate and transient families who often change from year to year (Heyward, 2002). These mobile students might also include a percentage of children referred to as Third Culture Kids (TCKs) or transnational youth (Tanu, 2018). ‘Type A’ international schools, like Ecolint, are often private institutions that cater to the diverse elite and globally advantaged (Gardner-McTaggart, 2018). International mindedness and global citizenship are overarching values of ‘Type A’ international schools (Tarc, 2018) due to their associations with accrediting bodies such as the Council of International Schools (CIS), Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC), and New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC). These schools also tend to adopt an international curriculum such as the International Baccalaureate (IB) (Silva-Enos et al., 2022), but may also specialise in more regional curriculums such as the French Baccalauréat, American Common Core or the British National Curriculum, with students aiming to complete their Baccalauréat (BAC) diploma, Advanced Placement (AP) courses, General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), or Advanced Level (A-Level) qualifications (Bates, 2011).

“‘Type B’ ‘ideological’ international schools: established principally on an ideological basis, bringing together young people from different parts of the world to be educated together with a view to promoting global peace and understanding” (Thompson & Hayden, 2013: 5).

‘Type B’ example: ‘Type B’ international schools are established with a clear vision of bringing together young people from different parts of the world to be educated in a shared environment. By doing so, they aim to foster a sense of global citizenship and mutual respect among students from diverse backgrounds. These institutions are not just centres of academic learning but are also hubs fostering cultural diversity, where students from various nationalities blend in, sharing their unique experiences while developing new, universal ones with their peers in the host country. In these ‘Type B’ schools, such as The Peace School, the emphasis is on creating a collaborative and inclusive atmosphere that transcends traditional educational boundaries. Students are encouraged to engage with each other’s cultural perspectives, leading to a richer understanding of global issues and the promotion of international harmony. This approach aligns with the schools’ ideological foundation, as they actively work towards building a more peaceful and interconnected world. By nurturing these values, ‘Type B’ international schools play a critical role in shaping the next generation of well-equipped leaders to navigate and contribute positively to our increasingly globalised society.

“‘Type C’ ‘non-traditional’ international schools: established principally to cater for ‘host country nationals’ – the socio-economically advantaged elite of the host country who seek for their children a form of education different from, and perceived to be of higher quality than, that available in the national education system” (Thompson & Hayden, 2013: 5).

‘Type C’ example: The initial step in the development of Type C international schools was recognising the growing demand among wealthy local families for an education that could provide a global perspective and competitive edge for their children. This demand was fuelled by the perception that the national education system was not adequately preparing students for the globalised world (Thompson & Hayden, 2013). To meet this demand, these schools designed a hybrid curriculum that integrates elements of internationally recognised programs, such as the International Baccalaureate (IB) or Cambridge International Examinations, with aspects of the local education system. This blend ensures that students receive a comprehensive education that respects local traditions and requirements while also providing a global outlook. Singapore International School (SIS) in Vietnam exemplifies the emergence of ‘Type C’ international schools. Established to cater primarily to the children of affluent Vietnamese families seeking a globalised education, SIS recognised the growing demand for an alternative to the traditional local curriculum (Nguyen, 2017).

International education’s illusion of an accurate definition is the result of the diverse and varied contexts schools are situated in (Poole & Bunnell, 2021), however it is acknowledged that international schools predominantly deliver curriculum in English, both in- and outside of English-speaking countries (Brummit & Keeling, 2013). It can be seen then that international schools are intricate social contexts (Grimshaw & Sears, 2008).

Defining diversity, equity and inclusion

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) has become public discourse across many industries. Much like international schools, defining DEI is a contentious topic, with various scholars and practitioners debating each component and its importance. Variations of DEI that you may come across include:

- Diversity, equity, inclusion, justice (DEIJ)

- Justice, equity, diversity, inclusion (JEDI)

- Diversity, equity, inclusion, belonging (DEIB)

- Equality, diversity, inclusion (EDI)

- Inclusion via diversity, equity, antiracism (I-DEA)

- Diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility (DEIA)

- Anti bias anti racist (ABAR)

For the purposes of our chapter, we will be using these definitions as defined by Arsel et al. (2022: 920):

“Diversity refers broadly to real, or perceived physical or socio-cultural differences attributed to people and the representation of these differences in research, market spaces, and organisations. Equity refers to fairness in the treatment of people in terms of both opportunity and outcome. Inclusion refers to creating a culture that fosters belonging and incorporation of diverse groups and is usually operationalised as opposition to exclusion or marginalisation.”

Key aspects

International schools: A global industry

The number of international schools is rapidly rising with currently over 5000 worldwide (Bates, 2023). According to Brummitt (2007, 2009), the most rapid growth is occurring in Asia (especially China), Europe and Africa. However, these figures may not reflect true reality due to the highly contested definition of international schools (Tanu, 2018). Our working definition for this chapter refers to three types of international schools as defined by Thompson & Hayden (2013; see above), and when discussing the rise of these types of international schools, two factors can be attributed. First, as a result of globalisation and the growth of the middle class in so-called developing countries (World Bank, 2007), there is support for the expansion of the ‘international school industry’ as theorised by Bunnell (2007) and MacDonald (2006), from an elite status to a more general status. Second, the education industry is generally gaining recognition as a global service industry worth billions of dollars (Bates, 2023), and its prospects for privatisation and commercialisation are highly valued (Susan Robertson, 2003). As a result, international schools are a global multi-billion dollar industry with double bottom lines, one educational and one business (MacDonald, 2006).

The growth of international schools is not purely numerical, as it has also coincided with the evolution of neoliberal ideologies in reorganising societies and social relations (Bates, 2023). Robertson (2008) elaborates that neoliberalism has three main goals:

“(1) the redistribution of wealth upward to the ruling elites through new structures of governance, (2) the transformation of education systems so that the production of workers for the economy is the primary mandate and (3) the breaking down of education as a public sector monopoly, opening it up for strategic investment by for-profit firms” (Robertson 2008: 12)

With this in mind, international schools vary widely, and the identities of these schools often deal with the tension between being market driven and ideology driven or falling on the spectrum between the two (Hayden & Thompson, 2008). As international schools are largely considered to be diverse hubs that are internationally minded and foster global citizenship (Tarc, 2018), the major issues that shape complex international school contexts and practices arise from the dichotomy between global culture and local culture in a global market (Bates, 2023). Tanu (2018: 5) explains that “international schools catered mainly to the children of expatriates, who made up 80 percent of the student body more than thirty years ago, rather than to local children, the trend has been reversed in recent years with local students making up 80 percent of the student demography.” It is clear that international schools are ecosystems full of tensions, differing interests and bottom lines.

Existing gaps in international schools

When international schools were first created and developed, the identity of these schools were often determined by Western countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada (Bates, 2011). With the specific target audience and clientele being largely expatriate, these international schools emerged to create a “school from home, away from home” (Gibson & Bailey, 2023: 410). As private institutions, international schools are complex social contexts (Grimshaw & Sears, 2008) that often form a community of diverse racial, cultural, and ethnic families (Brooks & Watson, 2019). In an increasingly globalised world (Bittencourt & Willets, 2018), where cultural, economic, and social divisions continue to widen (Putnam, 2015), schools need to be environments where diversity, equity and inclusion is fostered for all students (Riley, 2019). Interestingly though, Hayden (2011: 221) notes that “it is ironic, then, that schools that developed originally to promote greater social harmony and understanding between different people, as well as to facilitate mobility, seem to be contributing to a growing educational gap between social groups and thus to growing inequality in societies.”

Students spend a large portion of their youth at school, and developing a sense of inclusion and belonging is important (Maslow, 1954). At international schools, students are often forced to assimilate to the dominant culture, which is largely white and Western (Datnow & Park, 2008), and Anglo-Christian (Gardner-McTaggart, 2019). Reinforcing neoliberal and neocolonial ideologies, education sustains white supremacy at the most structural and societal levels, indoctrinating the dominant culture of whiteness and white privilege (Genao & Mercedes, 2021). This can lead to a divide between global and local culture, and identity confusion. Belonging, defined as being in a physical or virtual space where one can be confident and safe in one’s identity, while also feeling valued and at ease (Flewitt et al., 2017; Riley, 2017), is an important aspect within international school communities. Despite the need for international schools to foster belonging through diversity, equity and inclusion, across OECD countries there is a declining trend with 1 in 4 international school students feeling that they do not belong (OECD, 2017). This could be due to the dynamic and transient nature of expatriate international teachers (Caffyn, 2010), or the understanding that the diverse cultural, social and racial make-up of the school population adds another complex layer to developing a sense of belonging in a global community (Brooks & Watson, 2019). It is no longer enough to assume that diverse student populations (Khalifa et al., 2016) and core values of global citizenship and international mindedness (Hill, 2014; Tarc, 2018) are markers for belonging in international schools.

What are some of the gaps that exist in international schools that are hindering diversity, equity and inclusion?

Socio-cultural gaps

“International schools hold great potential as transformative spaces to initiate planetary action for peace, equality, justice and environmental change” (Gardner-McTaggart, 2020: 1).

International schools, particularly those offering the International Baccalaureate (IB), operate within a unique global space that is independent of any single nation-state’s political aims (Bourdieu 1996). Yet, while these institutions are unbound from national power structures, they often perpetuate a neoliberal ideology that has gained prominence in so-called Western democracies over recent decades (Gardner-McTaggart, 2020). This neoliberal orientation manifests as a form of cultural hegemony, where the international school landscape replicates Western, particularly Anglo European, values and norms under the guise of global education (Gardner-McTaggart, 2020). This globalised model not only reinforces social privilege and power but also promotes a largely uncritical adherence to Western ideals, cultivating a specific worldview in students that prioritises individual achievement and market-based values over communal or locally contextualised perspectives.

Despite a veneer of inclusivity, international schools often maintain an underlying framework of whiteness that pervades their curricula, staffing, and institutional culture. Predominantly led by white educators and operating with an unexamined Anglo-centric perspective, these schools risk advancing a limited view of global citizenship that may inadvertently obscure systemic issues such as colonial legacies and racial inequities. Even well-meaning initiatives, such as advisory programs and assemblies, that aim to address racism can fall short, treating it as an individual rather than a systemic problem, and leaving foundational power structures unchallenged (Bartoli et al., 2016). By examining the implicit racial and cultural biases embedded in international education policies and practices, it becomes evident that these schools play an active role in maintaining a globalised, Western hegemony, repackaging it as progressive education while neglecting critical interrogations of race and privilege (Gardner-McTaggart, 2016).

“How often did we as international students feel unrepresented in the course topics that were assigned to us? And how many of us, upon the death of George Floyd, felt the jolt of realisation that we know nothing about systemic racism, colonialism and its undiscussed modern successor?” (David, 2020: website)

In so-called developing countries, IB schools are typically private and cater to privileged demographics, whereas in Anglo European countries, the IB program is increasingly integrated within public (state) schools, appealing to middle-class families seeking high academic standards (IBO, 2012a; Resnik, 2012). Both of these reflect Type A and Type C international schools. This trend underscores the cultural capital linked to IB enrolment, which offers a sense of distinction and academic prestige (Bourdieu, 1984). The IB’s mission promotes so-called Western humanist ideals, encouraging intercultural understanding and lifelong learning with an appreciation for diverse perspectives (IBO, 2020a, 2020b). As part of a loosely regulated global market, IB schools are prized for their IB World School status, which positions them competitively within a neoliberal marketplace that capitalises on the demand for globalised, elite education.

Socio-economic gaps

Being international is an ideology that has shaped international schools and the transnational and national class structures of the global economy (Tanu, 2018). The theme of social class is not unusual in the literature on international education. Class analysis in the research on international education has been underscored to reveal the role of elite institutions in reinforcing the privilege of the elite class (Gaztambide-Fernández & Howard, 2010; Howard & Kenway, 2015; Kenway & Koh, 2015; Koh, 2014; Stevens, 2009). Therefore, the study of social class and international education overlaps with the research on elites and elite education to a large extent (Ball, 2015; Howard & Kenway, 2015; Weis, 2014; Weis & Dolby, 2012). The concentration of wealth in both so-called Western and developing countries has enabled emerging elites or ruling classes to afford enrolling their children in international schools. These parents hope their children will gain the qualifications and networks necessary to access their social class or the global professional labour market. MacDonald (2006: 198) estimated that these schools generate over 5.3 billion US dollars annually in tuition revenue. He also found that the average annual fee for international schools’ ranges from US$6,429 to US$10,451, with the highest recorded fee being US$54,264, which surpasses the fees of the British public-school Eton (MacDonald, 2006: 198). These statistics indicate that international school programs, regardless of their specific nature, are predominantly, though not entirely, attended by the wealthiest segments of the global population.

In contradiction with this line of research, Young’s (2018) case study on a type C international secondary school in Beijing discovered that most families under study held precarious social positions in an accelerating divergent society: most were members of ‘new rich’ entrepreneurial class or internal migrants. While these groups have a certain amount of economic capital, they lack other kinds of capital (for example social/cultural capital) to enable their children to progress or gain an academic advantage in the standard/local education system. For these families, the initial reason for enrolling their children in international education is not to obtain an ‘elite’ education or global citizenship mindedness, but to enable their children to pursue higher education. This type of international school provides a remedial rather than international environment when it comes to its academic program, which is a noticeable departure from the elite institutions depicted in the academic literature and popular media. In this case, the ‘new rich’ class families use their economic capital to help children accumulate cultural capital. This suggests that international education may accomplish different goals for different social groups, but financial resources are the condition for this education phenomenon.

Therefore, the socio-economic gap plays a significant role in shaping access to and participation in international education. On one hand, elite international schools tend to reinforce social class privileges by catering primarily to the wealthiest families, enabling their children to build the networks and accumulate the capital necessary for maintaining or improving their social status. These institutions serve as vehicles for the perpetuation of elite class structures and global economic advantages. However, not all families in international education fit this elite mould. As seen in Young’s (2018) study, some families, particularly from emerging entrepreneurial classes or internal migrant backgrounds, enrol their children in international schools as a way to overcome deficits in cultural or social capital. For these families, international education is viewed more as a remedial strategy to improve academic outcomes and secure future educational opportunities, rather than a path toward elite status. The primary unifying factor, however, is that financial resources remain the key determinant for accessing international education, although the motivations and benefits of such education differ across socio-economic groups.

In contrast to Type A and Type C international schools, Type B schools are less recognised as institutions that prepare students for advanced studies or an elite educational pathway. Instead, Type B schools primarily emphasise ideals of global citizenship, cultural diversity, and promoting peace through collaborative learning rather than exclusively prioritising academic advancement. This focus can create certain challenges for families when choosing these schools, as not all parents are primarily concerned with academic elitism or their child’s pursuit of advanced higher education. Some families may even consider alternatives, like homeschooling, to align more closely with their values and priorities.

Families choosing Type B schools often value a globally minded education and a supportive, inclusive learning environment. These parents may seek a balanced approach to education, one that combines personal growth with exposure to diverse perspectives, rather than focusing solely on academic achievement. It is difficult to categorise Type B school families within any particular socio-economic bracket. While not necessarily wealthy, these families prioritise a meaningful, well-rounded education and are willing to invest in it, even if it may require financial sacrifice. Ultimately, Type B international schools appeal to families who believe that fostering their children’s global awareness and intercultural understanding is as essential as traditional academic success.

There is yet to be a definitive solution to address the financial gaps faced by families considering Type B international schools. While some schools may offer financial aid or flexible payment plans to accommodate families from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, others provide no such support, leaving families to bear the total cost. Additionally, in certain countries, governments may offer financial assistance or tax reductions for families pursuing alternative education options; however, this is not universally available. Unfortunately, there is no consistent, globally applicable solution or support system for families interested in these schools, as Type B international schools are neither the dominant educational model nor widely recognised and supported by the public or governments.

Integrating diversity, equitable practices and fostering inclusion

Striving for diversity, achieving equitable practices, and fostering inclusion are essential components of a holistic educational framework that enhances learning and promotes belonging for all students. Holistic education recognises each learner’s uniqueness and diverse backgrounds, creating an environment where everyone feels seen, heard, and empowered. By incorporating diversity into the curriculum and facilitating collaboration among all participants, students are exposed to various viewpoints that foster empathy, respect, and appreciation for differences.

The Peace School emphasises the importance of collaboration in decision-making and planning, involving caregivers, students, and teachers and all staff. The school believes that education can be compromised if decisions are made unilaterally by any single group and underscores that people possess more power and ideas when collaborating, brainstorming, and sharing a common goal.

In traditional schooling, education and curriculum planning decisions in a behavioural approach or behaviourist schools are made solely by specialists. Education-specialised individuals decide what students should learn or study throughout their school years. The plan and schedule are mainly predetermined, with limited flexibility based on what students want to learn. In contrast, schools that follow a high-scope approach mostly rely on a student-centred approach, where curriculum and lesson planning revolve entirely around the students.

However, at The Peace School, we follow a humanist educational approach, where educational planning happens through the collaboration of all entities involved, including specialised people, teachers, parents, students, and even the community they live in. The curriculum is continuously prepared and adapted through ongoing interaction and collaboration among all entities, who constantly communicate to make the best decisions for the benefit of students.

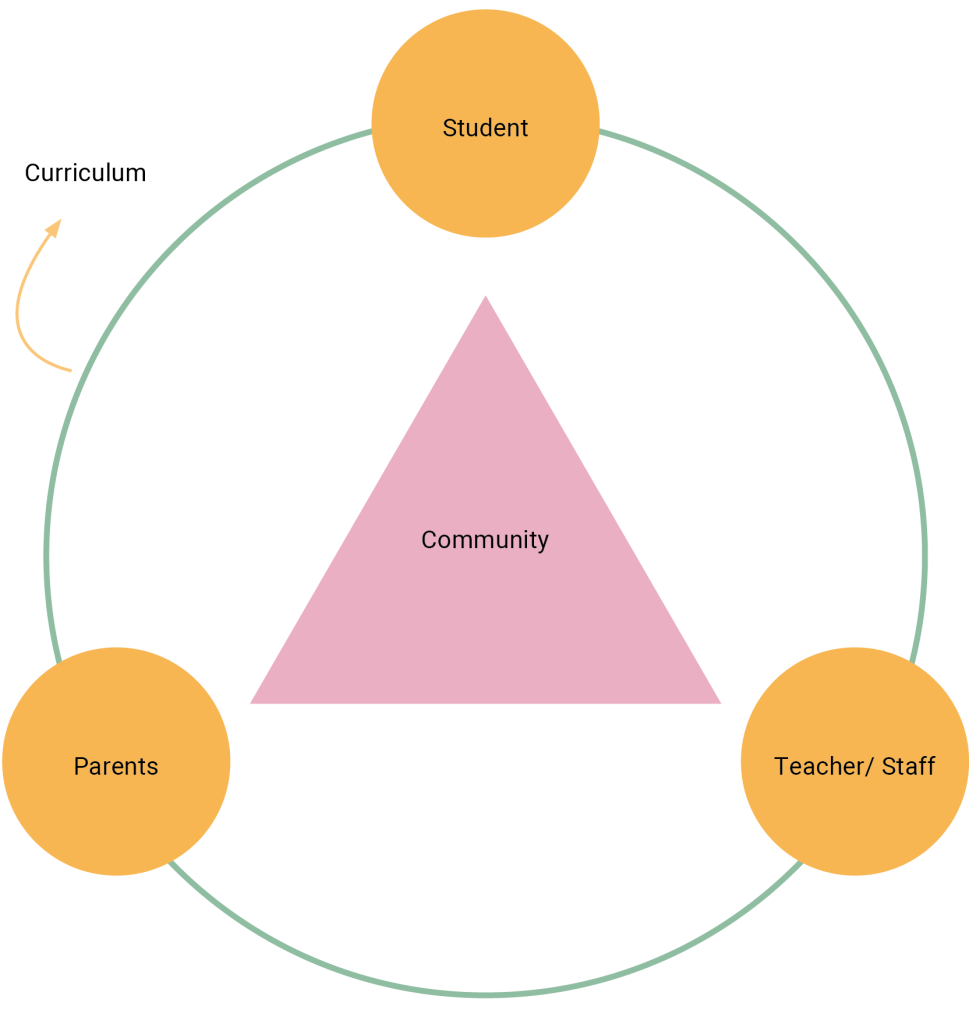

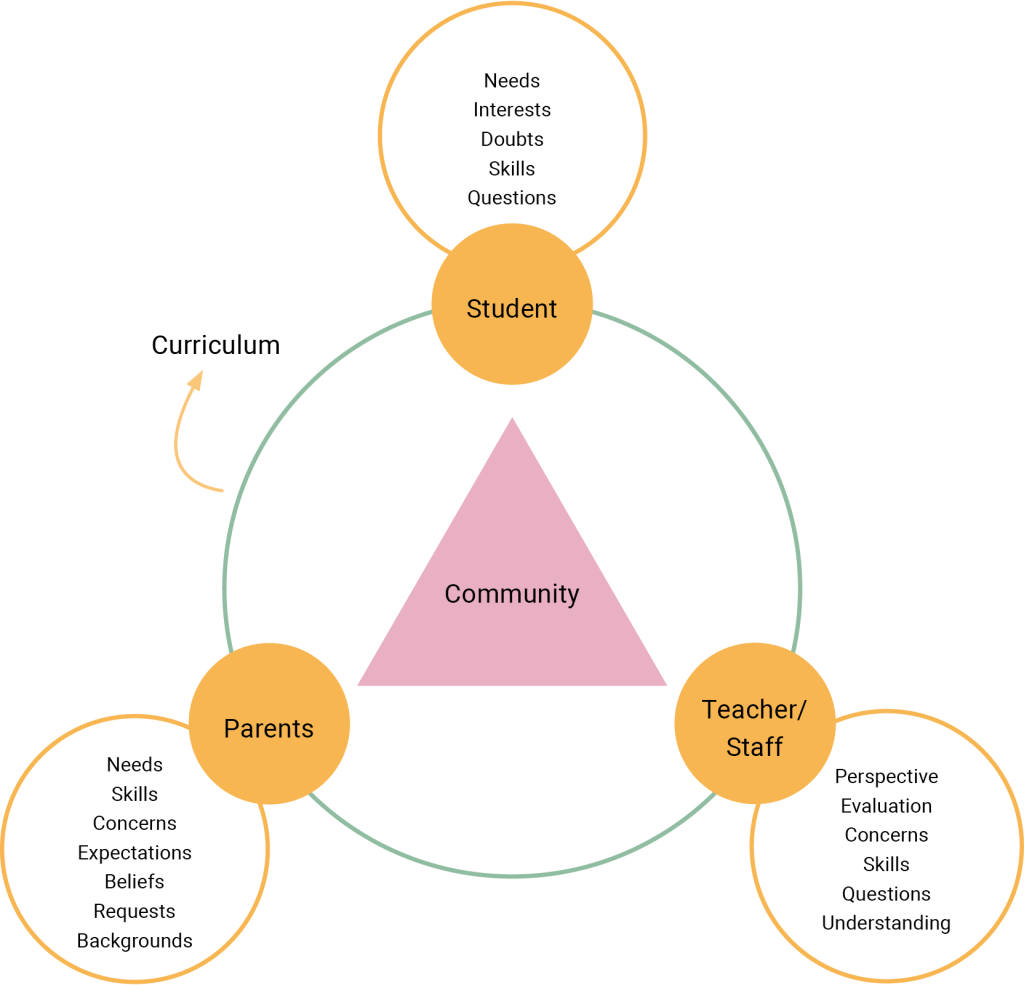

We have a framework we call the ‘Triangle’ (Figure 1). On the Triangle, the student is placed at the top, with parents and teachers/staff at the base, and the community in the centre. This triangle represents an ongoing, collaborative process among these three corners of education, connecting learning to our community and daily life. Each corner requires training, conversation, time, and a voice to express opinions without judgement.

Figure 1: ‘The Triangle’

Our approach begins with the child’s starting point, catering to their specific needs, abilities, and interests. We focus on sparking curiosity and creativity, emphasising project-based learning rather than a linear, behavioural approach based on universal textbooks. Teachers and staff provide valuable input on the educational process, as they spend several hours with students, observing their interests in learning. Parents’ input is also crucial as they can offer learning opportunities outside the school environment. Therefore, the essence of connectedness among these three corners is critical. The Triangle approach ensures a holistic, collaborative, and student-centred educational experience, fostering a strong sense of community and shared responsibility for each child’s growth and development.

Our approach begins with the child’s starting point, catering to their specific needs, abilities, and interests. We focus on sparking curiosity and creativity, emphasising project-based learning rather than a linear, behavioural approach based on universal textbooks. Teachers and staff provide valuable input on the educational process, as they spend several hours with students, observing their interests in learning. Parents’ input is also crucial as they can offer learning opportunities outside the school environment. Therefore, the essence of connectedness among these three corners is critical. The Triangle approach ensures a holistic, collaborative, and student-centred educational experience, fostering a strong sense of community and shared responsibility for each child’s growth and development.

Figure 2: ‘The Triangle’ – what each agent (student, parents, teachers/staff) bring to the classroom

Enrolment

Enrolment differs in each school type and requires its own specified process. The Peace School, a Type B international school aiming to foster collaboration and participation and committed to a humanist educational approach that integrates the principles of a culture of peace and living values, strongly encourages families to enrol their children early, ideally starting in preschool or Grade 1. The school’s experience has shown that students who join in the upper grades often face significant challenges in adapting to the unique educational system, which differs markedly from mainstream approaches.

To ensure that prospective families are fully informed and aligned with the philosophy, the school strongly emphasises caregiver involvement during the enrolment process. This begins with a general introduction session where they present the school’s values and educational approach. Following this, they invite families to participate in a 20-session camp held over 20 days, with each session lasting 2 hours specifically designed for new families. Each session focuses on a key principle or aspect of our educational philosophy, offering families a deep and comprehensive understanding of our school’s approach. This camp also provides an opportunity for families to meet and interact with the entire school community, including management, staff, and teachers.

The primary objective of these sessions is to equip families with the knowledge and insight necessary to make an informed and deliberate decision about their child’s education. Following the family sessions, the school conducts approximately ten orientation sessions for new students over the summer, with each session lasting an entire school day and held once a week, ensuring they are well-prepared and comfortable before the school year begins.

These orientation sessions are crucial in helping families and children acclimate to the school environment and culture. By making an informed decision after experiencing the school firsthand, parents and children can determine whether the school’s educational approach aligns with their expectations and aspirations.

Making an informed decision – after experiencing the school firsthand – caregivers and their children can decide whether the humanist educational approach aligns with their expectations and aspirations for their education.

Ultimately, this process fosters a strong partnership between the school and families, ensuring a smoother transition and a shared commitment to the child’s learning journey.

Recruitment

Like many educational institutions, The Peace School has evolved and refined its recruitment process over the past twenty years. While they have a preferred process in place, it remains flexible and can be adapted based on the individuals and circumstances involved. The school encourages all prospective teachers to immerse themselves in their school community by participating in regular department meetings. Each department, including science, mathematics, arts, literature, and more, holds weekly meetings where staff discuss lesson plans, share ideas, and develop collaborative projects across various grades.

In addition to these regular meetings, the school also holds inter-departmental sessions where, for example, science teachers may attend art department meetings to brainstorm and develop interdisciplinary projects for the students. It is essential for prospective teachers to attend these meetings before formally joining our teaching staff. This allows them to become familiar with the school’s methods and participate in several projects before they begin teaching classes.

The school also strongly encourages new teachers to enrol in a bespoke teacher training course. The course consists of ten classes over ten days, totalling 60 hours, and covers a wide range of topics, including educational approaches, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, living values and the culture of peace, children’s literature, play and games, drama, early childhood development, art, storytelling, project-based learning, and more.

This type of commitment to fostering collaboration and continuous professional development not only enhances the quality of education but also creates a supportive community where teachers can thrive and make a meaningful impact on their students’ lives.

Curriculum

As dictated by law, many international school teachers are working in schools and countries in which there are limitations on the kind of content educators can share with students. These limitations may range from content that accurately depicts shared racialised and ethnic history, to content that affirms LGBTQ+ identities. This is an acknowledged reality. Engaging in any approach to teaching and learning that centres diversity, equity and inclusion is going to be in direct opposition to the system that employs educators (Reid, 2024). Educators must continue to engage anyway, especially in international school contexts where the student body has a diversity of social identities in a myriad of ways.

For example, recent discussions of global citizenship education as a way to counter the “single narrative story” have noted the lack of critical analyses of global power relations and colonial histories that has left educators without frameworks to address the structures of inequality that shape students’ experiences of difference (Dyrness 2023). Taking a case study of an international school in Costa Rica, a typical Type A international school, many students perceived the IB’s formal curriculum as Eurocentric, finding it conflicted with the school’s goals for embracing diverse perspectives. An Eastern European student expressed disappointment that the curriculum sidelined cultural learning in favour of content dominated by Western perspectives. Another student from Asia, highlighted the prevalence of Western case studies in her Global Politics course, reinforcing the idea that the “global” is often framed through the lens of the Global North. Such critiques indicate a disconnect between students’ diverse lived experiences and the knowledge deemed valuable or relevant within the IB structure (Bourdieu, 1984). Students also noted how these limitations in the curriculum diminished opportunities to discuss pressing issues within their own communities, reflecting an implicit prioritisation of so-called Western knowledge systems.

In contrast, students found that co-curricular activities, such as Regional or Culture Weeks, allowed more space for sharing diverse perspectives, though they critiqued these events for their focus on celebratory and performative aspects of culture. A student from an Afro-Caribbean background, explained that these events often reduced cultural appreciation to superficial encounters with food, dance, and costumes, neglecting deeper issues like colonial histories or ongoing socio-political struggles. Similarly, a student from North Africa noted that while the school provided a platform to showcase culture, it rarely supported discussions of the challenges faced by their communities. Such events, as students observed, align with Melamed’s (2006) critique of “neoliberal multiculturalism,” where cultural diversity is idealised but stripped of discussions on race, class, and power. This sanitised approach to diversity promotes a form of “domesticated” tolerance (Andreotti, 2011) that leaves structural inequities unchallenged.

Students are crying out for a more affirming curriculum that really represents the diversity within the world, rather than an Anglo European or so-called Western perspective that is rampant in international schools across the globe, whether they teach the IB curriculum or any other internationally recognised state systems.

Assessment

In Type-A and Type-C international schools, one of the pervasive issues with assessment practices is their overwhelming focus on university admission requirements, which often distorts the broader educational experience. These schools tend to align their curricula and assessments with the standards set by higher education institutions, particularly international universities, rather than focusing on holistic learning or fostering critical thinking (Brummitt & Keeling, 2013). This phenomenon is especially pronounced in East Asia, where Type-C international schools cater to families seeking an alternative to the highly competitive local education systems. In these schools, teaching is often oriented toward preparing students for standardised tests, such as the SAT, A-levels, or IB exams, and meeting the specific criteria for applications to prestigious universities in the West (Bunnell, 2016). This narrow focus on assessment not only restricts the curriculum but also places students under immense pressure to perform academically, sidelining other important aspects of education such as creativity, emotional development, and extracurricular engagement (Doherty, 2009). Consequently, while these schools may provide a pathway to higher education, they contribute to an educational environment driven by instrumental goals rather than comprehensive learning.

At The Peace School (Type-B example of international schools) believes that the traditional model of individualised evaluation through exams and grades is inherently inhumane. The schools reject the behaviourist approach to education, which emphasises exams and grades as the primary tools for assessment. Instead, they advocate for evaluation methods that genuinely support students in deepening their understanding of subjects. In their view, evaluation should involve a collective effort that includes students, parents, teachers, staff, and the broader community.

Their assessment process is designed to focus on students’ holistic development, taking into account their emotional, social, ethical, and academic needs. They believe assessing aspects of a student’s growth that are often overlooked, such as their character, needs, interactions, and other values, is crucial.

However, they also recognise the importance of being mindful of our evaluation. What aspects of a child’s development should be the focus? Should we assess only their academic achievements or also their personal growth and memory? In humanistic schools like The Peace School, evaluation criteria are detailed, extensive, and adaptable. These criteria evolve over time and involve input from teachers, students, and families. For example, one student might be evaluated on their courage and encouraged to exhibit more courageous behaviours, while another might be guided toward greater patience and carefulness. In other words, the evaluation process is personalised to suit each student’s unique needs.

The schools employ various methods of assessment, including:

- Observation: A diverse group of observers, including teachers, administrative staff, counsellors, and families, continually assess students throughout different periods. This evaluation extends beyond the classroom to include observations during breaks, lunchtime, field trips, and other activities. Observing students in various contexts gives us a more comprehensive understanding of their development. All staff members are encouraged to share their insights and observations about students.

- Student Engagement: One of the most effective assessment methods is to involve students directly. This does not mean traditional verbal exams but rather engaging them in meaningful conversations. We ask questions that help identify their needs: Are there areas where you require additional support? Do you need to learn new skills? Are you struggling with certain subjects? This approach helps students become aware that their challenges have been noticed, and we are here to support them.

- Group Dialogue: Frequent group discussions where students can share their opinions and engage in discussions on various topics. This method allows the school to collaboratively assess their knowledge, awareness, and viewpoints.

- Collaborative Review: Teachers, staff, and caregivers – parents and on some occasions other family members, including the grandparents – meet regularly to discuss students individually and in groups. By gathering diverse perspectives, the team gain a holistic view of each student’s development and can tailor our approach to meet their specific needs.

These are just a few examples of how The Peace School integrates evaluation into our educational model, moving beyond quantitative assessment to create a more humane and comprehensive approach to student development.

How can international school teachers empower students?

In an increasingly interconnected world, international schools have a unique opportunity and responsibility to nurture global citizenship beyond traditional academic metrics. By embedding values such as diversity, equity, and inclusion into their curricula, international schools can empower students to become agents of positive social change. Programs like the International Baccalaureate (IB) facilitate this mission through courses and experiential learning opportunities that engage students in real-world challenges, such as the Theory of Knowledge (TOK) and Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS). Through these frameworks, students explore pressing global issues and cultural diversity while developing empathy, critical thinking, and a commitment to social responsibility. Partnerships with local organisations, initiatives on intercultural understanding, and active home-school collaboration further reinforce these values, allowing students to apply their learning toward creating inclusive communities. By integrating global citizenship into both academic and co-curricular activities, international schools prepare students to address systemic inequalities and advocate for a more equitable world.

Integrating Global Citizenship Beyond Academic Metrics in International Schools

International schools could play a vital role in nurturing global citizenship as a means of empowering students to become agents of change, particularly in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Global citizenship education focuses on fostering a deep understanding of cultural diversity, social responsibility, and global interconnectedness. Implementation of the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum could embed these principles through both academic and extracurricular activities. In the Theory of Knowledge (TOK) course, there are opportunities for students to critically examine global challenges, such as climate change, migration, and inequality, from multiple perspectives. Additionally, the Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS) program requires students to engage with real-world issues by participating in service projects that promote social justice and environmental sustainability. Teachers in their daily teaching practice need to be aware of the importance of implementing these values, rather than solely focusing on the quantitative results related to university admissions. For example, students at the International School of Geneva have engaged in projects to support Syrian refugee families through educational initiatives, helping to bridge language and cultural gaps while addressing immediate social needs. These experiences enable students to translate abstract concepts of global citizenship into concrete actions that promote equity and inclusion (Savva & Stanfield, 2018).

Intercultural understanding is another key component of how international schools promote global citizenship. By bringing together students from diverse cultural, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds, these schools offer daily opportunities for cross-cultural interactions. Schools often encourage these exchanges through structured programs like cultural festivals, language immersion days, and collaborative global projects. For instance, at the United World Colleges (UWC), students are deliberately recruited from different parts of the world to live and learn together, fostering an environment where intercultural dialogue is not just encouraged but is integral to the learning experience. UWC students are tasked with solving real-world problems collaboratively, often addressing issues such as global poverty, human rights abuses, or climate justice. One specific example is the UWC in Costa Rica, where students designed a sustainable community garden that integrates agricultural techniques from different cultures while addressing food security for marginalised local communities. Through this hands-on approach, students learn to see diversity not as a challenge but as a strength in solving global problems (Hill, 2012).

Furthermore, international schools can empower students to address systemic inequalities by integrating discussions of race, gender, and class into their academic programs. This helps students develop a critical understanding of how these issues manifest both globally and locally. For example, the British International School in Cairo offers a program called “Global Issues Network,” where students engage in debates and workshops on topics such as gender equality, racial justice, and economic disparity. These forums not only raise awareness but also require students to design and implement projects aimed at tackling inequities within their own communities. One notable project involved students working with local NGOs to develop an educational campaign addressing gender-based violence in rural Egypt, combining their academic knowledge with practical action. Through these initiatives, students are equipped with the skills and confidence to challenge discriminatory practices and advocate for more inclusive environments (Yosso, 2005).

Additionally, international schools can also support global citizenship through partnerships with local organisations that focus on social equity. The International School of Manila, for example, has partnered with Gawad Kalinga, a local nonprofit dedicated to eradicating poverty, to engage students in service-learning activities. Students not only participate in the construction of homes for underprivileged families but also work directly with community leaders to understand the social and economic barriers these families face. This kind of collaboration teaches students about systemic inequities and empowers them to take meaningful actions to address them. Such experiences help students see the interconnectedness of global and local issues, encouraging them to become advocates for change in diverse contexts (Gaudelli, 2016).

Empowering: A New Framework on Empathy, Compassion, and Responsibility

Every individual possesses a full range of human qualities, such as empathy, compassion, responsibility, freedom, etc. What matters is which of these qualities we nurture and provide opportunities for growth and expression. Many human values should be practised with children, allowing them to experience them. If we do not offer students these opportunities, we hinder their chance to develop and allow positive traits to emerge. As Gramsci (1971) states, “Men are not born free; they become free.” This illustrates that no values are inherently present in humans; rather, they require active engagement and practice to be acquired.

To provide opportunities to learn and practice values such as empathy, compassion, and responsibility, The Peace School dedicates classes titled “Understanding Living Values,” following the curriculum recommended by the Foundation for Living Values. However, they recognised that these important topics should be open to more than just one class. Subjects like empathy, love, respect, co-operation, and kindness are universal themes that should be woven into the fabric of every lesson across all subjects. This realisation led them to explore how to integrate discussions, or dialogues, on empathy, compassion, and responsibility into subjects like science, history, literature, mathematics, and beyond. While classes like art, literature, and history naturally aligned with this initiative, maths and science teachers were initially uncertain about how to incorporate these themes into their lessons.

In the science department, one class began by reading Frans de Waal’s insightful book on empathy and designed lessons, activities, and discussions around the concepts it introduced. However, many maths teachers initially wondered whether topics like empathy and compassion were relevant in a maths class. Despite these reservations, the school’s team discovered a unique way to experience and teach empathy through mathematics.

While preparing a lesson on percentages, one teacher posed practical questions to the students: What percentage of the school’s students are girls? What percentage are between the ages of 9 and 10? What percentage of parents are doctors? The students analysed various data points and calculated the percentages accordingly. One set of data focused on the mortality rate in traffic accidents, specifically the statistic that one out of every hundred people worldwide die due to a car crash. For some students, this 1% statistic didn’t seem particularly alarming; many believed that the death of one person out of a hundred was not cause for concern. Sensing the need for deeper reflection, the maths teacher encouraged the students to consider the human story behind this statistic.

Together, they began to ask: Who is this one person? They reflected that this individual, reduced to a mere number in the statistic, could be someone’s mother, father, sister, brother, or child. Is this “one” just a number for that person’s family? What if this one person out of a hundred was someone close to us? Would it still be just a number? What if this one person was you or me? Can we say that one person out of a hundred isn’t significant and doesn’t warrant concern?

This line of questioning sparked a transformative project. The students, guided by their teacher, reached out to families who had lost loved ones in traffic accidents. They listened to these families recount the emotional impact of their loss and how they coped in the aftermath. For a parent who has lost a child, is the number “one” in maths merely a number?

This project expanded into a broader initiative focused on preventing traffic-related deaths. Following this experience, the students’ empathy for the news and statistics they encountered grew significantly. They began to connect more deeply with the data on children suffering from malnutrition, those caught in war zones, displaced by conflict or facing other life challenges.

In the maths class, numbers took on a new, profound meaning. No longer could anyone dismiss a percentage as too small to matter. Even if just one person is harmed to these students, it is one too many.

In conclusion, by embedding values such as empathy, compassion, and responsibility into the curriculum, schools like The Peace School not only enhance students’ academic learning but also prepare them to become compassionate, engaged citizens. This holistic approach fosters a deeper understanding of the world and promotes the development of a caring and responsible community. Ultimately, cultivating these values from an early age empowers students to make meaningful contributions to society.

The Role of Home-School Collaboration

In international schools, the relationship between families and schools serves as a foundational pillar for empowering students to become agents of change, particularly in the realm of fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). This collaborative effort between educators and parents creates a dynamic environment where inclusive values are consistently modelled and reinforced, both at school and at home. Research has demonstrated that active parent engagement enhances student outcomes by promoting a shared understanding of the educational and social goals, including the importance of DEI in students’ daily experiences (Hill & Tyson, 2009). In the context of international schools, which often cater to diverse student populations from various cultural, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds, the family-school relationship is even more critical. By aligning the home environment with the school’s DEI mission, students are better equipped to internalise these values and apply them in their communities.

A key element of this partnership is clear and sustained communication between the school and parents. International schools can facilitate this through regular workshops, informational sessions, and open forums where issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion are discussed openly. For example, the International School of Kuala Lumpur (ISKL) has established a “Parent Engagement Program” where parents are invited to participate in DEI workshops alongside educators. These sessions provide a platform for both parties to discuss strategies on how to address and support diverse identities within the school community. The outcome of such communication fosters a collective responsibility for nurturing an inclusive school culture. Students, observing the collaboration between school and home on issues of DEI, are more likely to see these values as integral to their own actions, thus enhancing their capacity to be agents for social change. Indeed, while fostering a shared commitment to inclusive values is beneficial, it’s also essential to recognise and respect the diversity of perspectives that families may bring to the table. Acknowledging and navigating these differences can, in fact, enrich the learning environment, as it helps students understand and engage with the complexities of diverse worldviews and value systems. This approach not only prepares students to handle real-world contradictions but also underscores for teacher candidates the importance of flexibility and cultural humility in promoting DEI.

Moreover, international schools often encourage parents to participate in co-curricular activities that celebrate and promote cultural diversity. For instance, some schools, like the United Nations International School (UNIS) in New York, organise annual “International Fairs” where families can represent their respective cultures through food, performances, and art. These events highlight cultural diversity in a positive, celebratory manner and actively involve the school community in appreciating and respecting different cultural backgrounds. Through such involvement, parents help create a school culture that celebrates diversity, thus showing students the value of inclusion through action. The presence of parents at these events as active participants reinforces the idea that diversity is not simply an abstract concept discussed in classrooms but a lived experience that needs to be nurtured within the community. This can though, as discussed earlier in the curriculum section, be seen as performative, and should therefore be done in conjunction with a robust and diverse curriculum that sits alongside the co-curricular program.

In addition, governance structures such as parent diversity committees or advisory boards provide another avenue for parental involvement in DEI efforts. Schools that establish diversity committees with parent participation, such as the American School in London (ASL), empower both parents and students to take leadership roles in creating more equitable school environments. These committees often work on policy recommendations, develop anti-bias training, or spearhead initiatives like inclusive curriculum development. When students witness their parents contributing to such initiatives, they are more likely to view themselves as stakeholders in efforts to promote equity and inclusion. This active parental involvement not only enhances the school’s DEI initiatives but also serves as a practical demonstration for students on how they can take leadership roles in their communities and beyond.

Finally, home-school collaboration enhances students’ leadership and advocacy skills by fostering an environment where critical thinking about global inequities is encouraged. For example, at the International School of Brussels (ISB), the school’s collaboration with parents on sustainability and social justice projects empowers students to address global challenges in meaningful ways. Parents are invited to participate in and mentor student-led initiatives such as the “Green Schools” project, where students take the lead in reducing the school’s carbon footprint. By working alongside their parents and teachers, students gain the confidence and skills to advocate for global change on issues related to environmental sustainability, which directly aligns with broader DEI goals, as climate justice is deeply intertwined with social equity.

In conclusion, the collaboration between international schools and parents is essential for cultivating students who can act as agents of change in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Whether through enhanced communication, participation in cultural events, involvement in governance structures, or collaboration on global initiatives, parents play a crucial role in reinforcing the DEI values that schools seek to instil. By involving parents in meaningful ways, international schools not only create a supportive environment for students but also empower them to take these lessons into the world, advocating for inclusivity and equity in their future endeavours.

Reflection on the Concept of “International Schools”

The notion of “international schools” often conjures images of a globalised educational environment, designed to cater specifically to expatriate communities and students from diverse backgrounds. However, it is imperative to critically examine the implications of emphasising this concept. Why should the label of “international schools” be confined to certain institutions, and what does this mean for inclusivity within education?

Emphasising the international nature of these schools can inadvertently create a form of exclusion. By designating certain institutions as “international,” there is a risk of marginalising local educational systems and the students who belong to them. This distinction can foster a perception that international students are inherently different or superior to local students, leading to a bifurcated educational landscape (Perkins & Neumayer, 2014). The reality is that educational inclusivity should transcend these labels, as effective education is fundamentally about embracing diversity in all its forms.

The differences between international and local students often revolve around cultural, linguistic, and experiential factors. International students may come from various cultural backgrounds and possess different educational expectations and experiences compared to their local counterparts. Nevertheless, the distinction is not as clear-cut as it may seem. Local students may also embody significant cultural diversity and linguistic variations that deserve recognition and accommodation within the educational framework (De Jong & Harper, 2021). Therefore, the dichotomy between international and local students often oversimplifies the complex tapestry of student identities and experiences.

As educators committed to advancing inclusive education, it is crucial to recognise that the strengths of international schools lie not only in their global focus but also in their ability to embrace the rich diversity of students’ backgrounds. Respecting and valuing the different cultural, linguistic, religious, gender, sexuality, class and ideological perspectives of all students is essential for fostering an inclusive educational environment. This approach not only enriches the learning experience but also prepares students to navigate an increasingly interconnected world (Banks, 2019).

In conclusion, while the concept of “international schools” holds significance in promoting a globalised education, it is vital to approach this label with caution. Educators must strive to dismantle the barriers that these distinctions can create and work towards fostering an environment where all students, regardless of their backgrounds, feel valued and included.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

As authors of this chapter, we have only scratched the surface of international schools and their ability to foster or hinder diversity, equity and inclusion. Further questions that could be explored include:

- What are the specific impacts of the three types of international schools on inclusion? Do they offer different perspectives for the future or are they in “different stages of development?”

- How do educators deal with diversity, equity and inclusion in international schools within the neoliberal field of the education industry on a global scale?

- How can international schools grapple with the impact and influence of whiteness on power structures, hiring, curriculum and co-curriculum?

- What hidden curriculum is being perpetuated across international schools?

- How will international schools impact the future of so called developed and developing countries? What are the challenges, and do they pose issues of white saviourism?

- How can democratic education impact international schools?

Literature

About the authors

name: Baran Yousefi

Baran Yousefi holds a degree in Health Studies from York University in Toronto, Canada. As a graduate of the Participatory School, Iran’s first alternative and democratic school, she brings extensive hands-on experience in educating children through a humanistic approach. Currently, she serves as the coordinator and a key member at the Peace School in Toronto, and she is a board member of Humanist Kids. Baran is deeply committed to promoting humanistic values and fostering a culture of peace through education. She has completed numerous courses in educational methodologies, UN sustainable development programs, and participatory systems, all of which align with her dedication to humanistic psychology and UNESCO’s peace charter. Her unique blend of lifestyle, educational philosophy, lived experiences, and academic background has positioned her to make a meaningful impact in the field of children’s education.

name: Kristina Pennell-Götze

Kristina Pennell-Götze (she/they) (M.Ed) is a queer Filipino-Australian social change agent, focusing on diversity, equity, inclusion, justice and antiracism (DEIJAR) in international education. She is an educator and leader with experience working in public, private and international schools in England and Germany. She is the facilitator of the student Social Justice Committee and the Gender and Sexuality Alliance groups, providing support and opportunities for students to lead. Kristina is a leader within Association of International Educators and Leaders of Color (AIELOC), and a former fellow of the organisation, providing guidance and support to educators and leaders who are AIELOC school and community members, in addition to creating space for BIPOC to lead and share. Additionally, Kristina founded the Association of German International Schools’ (AGIS) Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Justice (DEIJ) working group and developed the first DEIJ student-led conference hosted at the Bavarian International School in 2024. She has led multiple workshops and keynoted on topics related to DEIJAR at various conferences around the world and online.

name: Linjie Zhang

Linjie Zhang is a researcher at the University of Vienna. Her primary research interests encompass structural inequality within the educational system, the development and management of international schools, elite education, neoliberalism and globalization, educational policy, and the application of capital theory in education.