Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Accessibility of Media and Materials

Thomas Joseph O Shaughnessy; Pamela February; and Sam Blanckensee

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

A School-wide application for Accessible Documents

Mx May had a student with low vision join their class and required all class media and materials in an accessible format. Mx May had realised that she had never really considered making her curriculum accessible before, so she decided she would make a concerted effort to change the structure of her digital content to support this student.

Mx May followed the Accessibility Resources and Know-How (ARK) online resource by the Association on Higher Education and Disability and learned how to create accessible content. She began to add headings to her documents, alternate text for images and include descriptive links. She also added accurate captions to all her video content.

However, Mx May noticed that other students in the class, not just disabled students, began interacting with the documents. She realised that the learners could navigate and engage more with the material she was providing. She also noticed that students who used assistive technology voices, including screen readers, and text-to-speech, could access the material more readily. For one student with a disability who used text-to-speech, found this new approach had been a life-changing event.

Mx May also witnessed that learners who were learning in a language that was not their first language also seemed to benefit. They commented that the captions on videos had made it so much easier to comprehend what was discussed in the video content.

Mx May had not foreseen the wide-ranging benefits of introducing accessible materials. Mx May felt obliged to share this information with her peers and the broader school network during staff training. Mx May saw it as pivotal to developing inclusive culture within her school.

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What are the benefits of providing accessible media?

- How can educators create accessible media?

- How does stigma on technology affect accessible media?

- How can we expand the communities of practices to the broader community?

Introduction to Topic

Every classroom is unique, with learners from various social and cultural backgrounds demonstrating different abilities and exhibiting diverse interests and preferences for engagement. As a result, educators need to be cognisant of the needs and supports of this diversity if they are to create a more inclusive classroom environment. Moreover, the level of diversity in our classrooms has never been so prevalent. For example, over 15% of people in the European Union, almost 80 million people, have some form of disability (Mehigan et al., 2022). However, disability is only one aspect of our inclusive sphere. Globalisation due to migration, conflict, political differences, and commercial and social opportunities has resulted in increasingly diverse societies (Rios & Markus, 2011). These changes have significantly impacted the diversity within our school environments, as schools tend to be microcosms of society (Bialostocka, 2016).

Increasingly socio-ethnically diverse classrooms are also reshaping classroom interactions (De Schaepmeester et al., 2022). This socio-ethnic diversity can also impact the need for accessibility and more accessible practices. Parton (2016) echoes this sentiment noting a link between diversity and accessibility where accessibility can impact learners from every nationality. Accessibility is also about equity of access, no longer a niche requirement solely used by learners with a disability (Edyburn, 2010). Therefore, policies and practices in teaching and learning must be reviewed to guarantee that education is inclusive to everyone, not focusing simply on one cohort, the learners with a disability (Moriña, 2017; Zorec et al., 2022).

Although equity of access in education is a human right, there is a lack of emphasis on assistive technology and accessibility across the continuum of teacher education. There is a particular need for more training in accessibility and assistive technology in Initial Teacher Education (Michaels & McDermott, 2003; O’Sullivan et al., 2021; Van Laarhoven & Conderman, 2011; Wynne et al., 2016). While educators may have a moral and ethical rationale to develop accessible media and materials, it is often policy and legislation, both domestic and international, that drive accessible practice. Examples like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) from 2006, an internationally recognised and supported treaty, includes sections specifically related to accessibility and equity of access under Article 9. This well-supported convention additionally commits member states to support people with a disability so that they receive the necessary support within the mainstream education system under Article 24, including instruction on assistive technology.

More recently, the European Union Web Accessibility Directive (WAD) 2016, requires all new public sector websites and mobile applications to be accessible by 2021. This EU directive has two primary objectives, one which focuses on the promotion of accessibility and the inclusion of everyone, and the latter which targets the reduction of litigation based on issues related to accessibility (Lewthwaite & James, 2020). Interestingly, the WAD is not disability-specific legislation, instead reinforcing the benefits of accessibility for everyone. This directive has the potential to significantly impact accessible and pedagogical practices (O Shaughnessy, 2021). The WAD also aims to ensure EU citizens can participate in society on an equal basis while guaranteeing member states must amend their laws to meet the need of this legislative framework (Mehigan et al., 2022). The Web Accessibility Directive requires Member States to report on the results of their monitoring activities every three years (European Commission, 2023).

In addition to the WAD, policies such as the Digital Education Action Plan (DEAP) also impact accessible practice (European Commission, 2020). This European Union (EU) policy initiative supports the sustainable and effective adaptation of EU member states’ education and training systems. The DEAP noted how the global pandemic highlighted several existing challenges and inequalities in education and confirmed the need for improved levels of digital capacity in education and training (European Commission, 2020). The DEAP, which has inclusivity embedded across many of its key actions, was seen as a cooperative long-term strategic vision for high-quality, inclusive, and accessible European digital education. European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [EASNIE] (2022a) reiterates the Digital Education Action Plan commitment to include the accessibility of technologies and digital content. However, they also note the strong influence of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) on both accessible design and accessibility-centric legislation.

However, the DEAP is not without its critics. Some emphasise the DEAP’s lack of financial strategy for implementation, while others highlight concerns about its language and remit (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022a; Mauraille, 2020). Despite this, the DEAP has begun to influence and shape practice and policy. For example, the release of the Irish Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027 refers explicitly to its alignment with the Digital Education Action Plan, acknowledging its European expertise and suggesting it as a valuable tool to guide and assist approaches in Irish education (Department of Education, 2022). Accessibility is also an integral part of the inclusive teacher role. EASNIE’s ‘Profile for Inclusive Teacher Professional Learning’ includes valuing learner diversity and concepts of inclusion, equity, and quality education and supporting all learning (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022b). Despite a lack of specific reference to accessibility within this professional learning, the approaches within the publication entwine with a universal whole-school approach to accessibility, one which targets inclusion, equity, and access for all.

Divided into several sections, this chapter adopts a holistic approach to accessibility. The first section begins by discussing accessibility and assistive technology. The subsequent section examines the accessibility of media and materials, providing examples of how they can make their classrooms more accessible. The following section discusses the benefits and opportunities created when educators ensure that the media and materials used in schools are accessible. The next section will focus on the barriers educators encounter when creating accessible media and materials and will show some solutions to these barriers. This chapter shows what is currently available, although this is an area that is constantly changing with the availability of technology and new developments, this availability differs geographically, and access may vary depending on the technology currently used within the educational setting. The chapter then discusses the role of communities of practice and school management in shaping the inclusive culture within schools, which supports and promotes accessible media and materials. The chapter concludes with a summary of the chapter and possibilities for the future.

Key aspects

Accessibility & Assistive Technology

It is challenging to discuss accessible media without first mentioning what is meant by accessibility. Accessibility can have a range of meanings and is often used in an educational context to signify availability rather than ease of access, inclusion, or assistive technologies. Even when used within this context, the literature identifies varying definitions of accessibility (O Shaughnessy, 2021). Several authors have defined accessibility as providing equitable services and systems that support everyone and prevent practices from excluding anyone (de Witte, Steel, Gupta, Ramos, & Roentgen, 2018; Shachmut & Deschenes, 2019). However, given the increasingly socio-ethnical diversity of today’s classrooms, the authors have decided to embrace a more open view of accessibility. They draw on a publication from 2015 which discusses accessibility as a ‘celebration of diversity’ which ensures all learners are included within the learning process (Ahmad, 2015: 73).

There is also an intrinsic link between assistive technology and accessibility. This link exists because assistive technology is decisive in promoting accessibility and inclusive education (Ismaili & Ibrahimi, 2017). However, the definition of assistive technology provokes widely varying responses from the education community (Boone & Higgins, 2007). The U.S. Assistive Technology Act (2004) defines assistive technology as both the device and a service where assistive technology is “any item, piece of equipment, our product system, whether acquired commercially off-the-shelf, modified or customised that is used to increase, maintain and improve functional capabilities of the child with a disability” (U.S. Department of Education, 2004: 8). A common thread within the definition of assistive technology is its role in ‘increasing the functional capabilities’ of a person with a disability (Bowser et al., 2015; World Health Organisation, 2019). However, in terms of supporting a social approach, this chapter broaches assistive technology more as accessible and inclusive tools that may increase functional capabilities and as tools that can promote access, foster collaboration, and enhance productivity. These tools include text-to-speech, speech-to-text, graphic organisers, and inbuilt accessibility tools. These tools are often used as basic arguments behind classroom requirements for accessible media and materials. This chapter’s approach to accessibility and assistive technology is rooted in the knowledge that equity of access is no longer a niche requirement solely used by disabled learners (Edyburn, 2010; Moriña, 2017).

Creating Accessible Media and Materials: Benefits and Opportunities

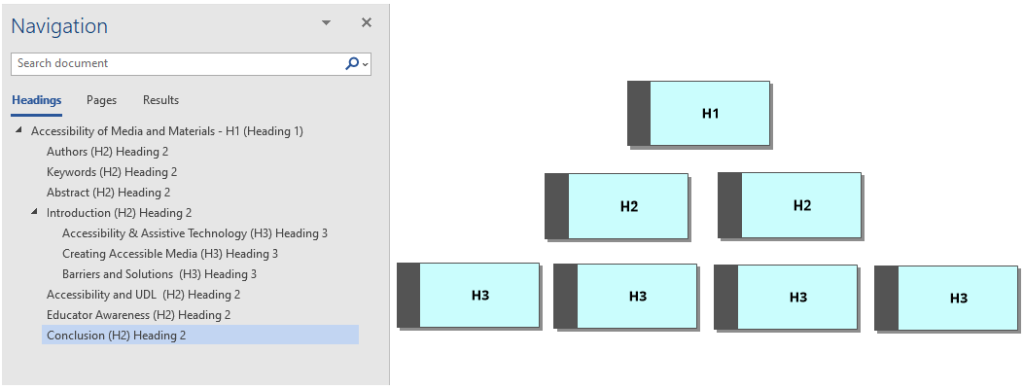

Creating accessible materials may seem like a daunting task to many educators. Often, they may not even know how to start the process. Of course, creating accessible content may depend on the technologies available to educators within a particular school. However, a simple start in supporting accessible media lies in creating documents and materials with structure. Materials, including long documents, especially books, are much easier to navigate for everyone when they have structure applied to them. There are multiple ways to do this, depending on the platform and software being used. In this example, Microsoft Word, a common word processor used across educational institutions from primary to postsecondary is used. However, alternatives like Google Docs and OpenOffice have similar supports around accessibility. Document structure in Microsoft Word is achieved by applying headings throughout your document using the Styles section on the Home ribbon. Screen readers, voice recognition, and keyboard users rely heavily on document structure for access and navigation, but Headings also allow everyone to engage efficiently. Applying Headings using a tiered approach creates a document tree, allowing all users to move up and down the headings contained within the document (as shown on the left in Figure 1). This makes navigation easier for both learners and educators.

Figure 1: Headings in Microsoft Word

Outside of the structure, other factors can affect the accessibility of a document (see Table 1). For example, font type, font size, and bullet/numbered lists are essential to enhance accessibility and are easy to apply. In terms of font size, word processor documents should be a minimum of 12 points (pt). Accessible font types include Century Gothic, Tahoma, Calibri, Helvetica, Arial, and Verdana. All these fonts are plain sans-serif fonts. The decorative nature of serif fonts can make them much more difficult to access and read. However, Comic Sans font, sometimes prescribed for students with dyslexia, can make documents inaccessible to assistive technologies used by some dyslexic students. When making lists in Word, always use the bullets and numbering feature. Marking items as a list informs the reader that there are a set of steps or a numbered sequence to a process (McGinty, 2020).

Outside of the structure, other factors can affect the accessibility of a document (see Table 1). For example, font type, font size, and bullet/numbered lists are essential to enhance accessibility and are easy to apply. In terms of font size, word processor documents should be a minimum of 12 points (pt). Accessible font types include Century Gothic, Tahoma, Calibri, Helvetica, Arial, and Verdana. All these fonts are plain sans-serif fonts. The decorative nature of serif fonts can make them much more difficult to access and read. However, Comic Sans font, sometimes prescribed for students with dyslexia, can make documents inaccessible to assistive technologies used by some dyslexic students. When making lists in Word, always use the bullets and numbering feature. Marking items as a list informs the reader that there are a set of steps or a numbered sequence to a process (McGinty, 2020).

The appropriate use of alternative text, link descriptions, and tables all play a role in creating accessible Word documents. Alternative text (alt text) is a text-based substitute for non-text elements, including images and tables. The alternative text aims to describe relevant information contained within non-text elements concisely. When applying alternative text, there is no need to begin the text with ‘Picture of’ or ‘Image of’, as it is superfluous and automatically assumed by the user accessing the alternative text. When describing the image, context is everything, so there is no need to include every piece of information within the non-text elements. Instead, the educator should focus on conveying the insight, the main trends, or the point of the graph or image. Link or hyperlink descriptions allow the user to understand the context of where the link will take them. While this is essential for screen reader users, its logical approach provides clarity and should benefit everyone, not just those using specific technologies. Poorly labelled links include common non-descriptive links ’Click here’, ‘Learn more’ or ‘link’. Moreover, document or page links with a long and complex link name with special characters may also create access barriers. Providing descriptive naming conventions or utilising link shorteners can alleviate these accessibility concerns (Chee, Davidian & Weaver, 2022).

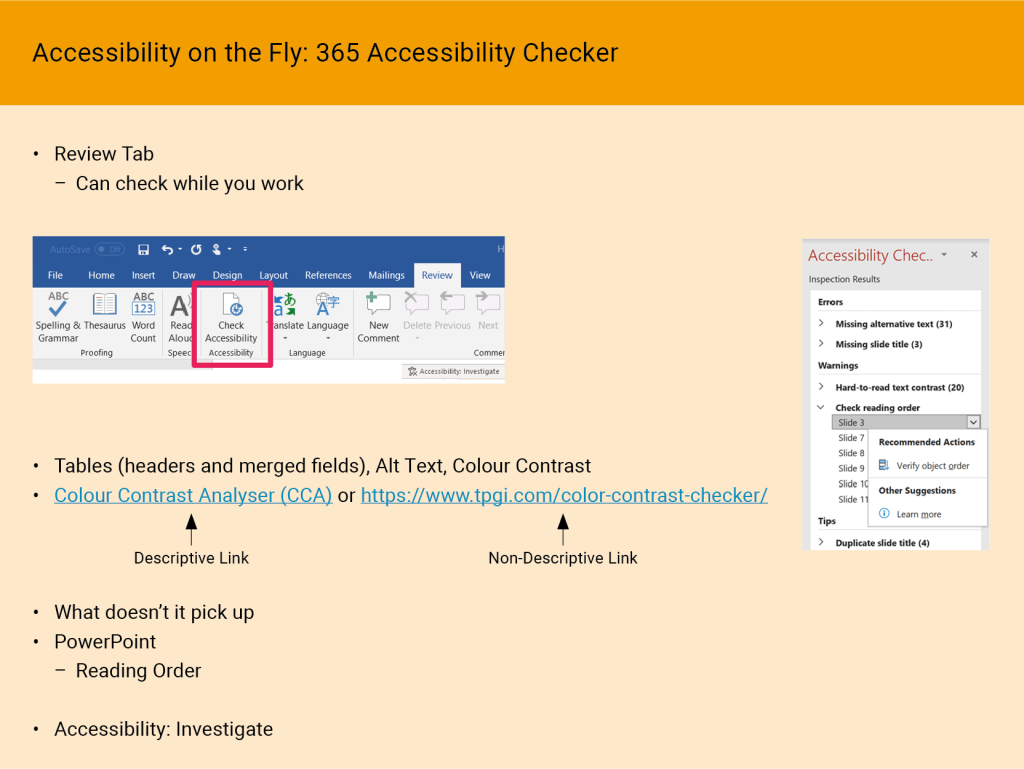

Figure 2: Accessibility in Microsoft Office

Table accessibility is usually more specific to screen reader users. Tables are read by the screen readers using header column cell and row cell to give the user context, especially if the user is blind or has low vision. Therefore, each cell in a table needs to have an associated header cell, so that when a screen reader user reads cell by cell the appropriate header data is read and the data within each cell is read. For more information see here an Introduction to accessible tables and a screen reader demo. If a header row is not applied, this creates an access problem for screen reader users. A similar situation occurs if fields within a table are merged as the screen reader cannot correlate the header column cell with the correct row cell. For more information see JAWS Reading Combined Tables.

Table accessibility is usually more specific to screen reader users. Tables are read by the screen readers using header column cell and row cell to give the user context, especially if the user is blind or has low vision. Therefore, each cell in a table needs to have an associated header cell, so that when a screen reader user reads cell by cell the appropriate header data is read and the data within each cell is read. For more information see here an Introduction to accessible tables and a screen reader demo. If a header row is not applied, this creates an access problem for screen reader users. A similar situation occurs if fields within a table are merged as the screen reader cannot correlate the header column cell with the correct row cell. For more information see JAWS Reading Combined Tables.

By applying accessibility throughout your content, educators make it easier to create more accessible alternative formats, for example, braille files, audio files including DAISY files, portable document format (pdf) files and HTML files. Web services like Robobraille at https://www.robobraille.org/ offer free format conversions for learners.

PowerPoint works on a similar premise to those mentioned above. However, reading order can play a vital role in this presentation tool. Screen readers navigate through slide content based on a structured order beginning with the title and then working through the slide in the order elements were added to the slide. If a teacher adds content outside of the template layout the reading order may be affected and require fixing. The Reading Order Pane can be accessed via the Check Accessibility drop-down pane in the Review Tab in PowerPoint. To enhance PowerPoint accessibility further, educators can use verbal descriptions of non-text elements when presenting their slides to support a more diverse audience. The application of colour is another integral part of accessible practice in Word and PowerPoint. Applying sufficient colour contrast ensures learners can visually access educational content. Although accessible colour contrast can be difficult to gauge, downloadable tools like TPGi’s Colour Contrast Analyser (CCA) offer learners and educators a contrast support solution. This tool allows you to compare colours and provides pass/fail results based on WCAG standards for colour contrast. For accessibility, colour contrast ratio between the text and the background above 4.5:1 and 3:1 for large text. This ratio can be checked using the CCA. Regarding accessible font size in PowerPoint, 24 pt should be the minimum applied. PowerPoint also allows educators to search for pre-designed accessible slide templates which utilise accessible colours for contrast and reader-friendly font styles. For many reasons, including for learners with low vision and colour blindness, educators should never use colour to convey meaning alone. Moreover, when emphasising a point, it is best practice to use plain text where possible and to not use colour or bold font as a sole way for relaying important information as this can create barriers for a range of learners, for example, screenreader users, learners who have low vision, and learners with colour blindness (Arch & Abou-Zhara, 2008).

The issue of time is sometimes a factor when it comes to creating accessible media and materials. Schools, management, and educators need to develop school environments where implementing accessible practice is the new norm. Tools to support this initiative already exist, for example, Google Docs has an option to turn on screen reader support. Microsoft has the Accessibility Checker, a tool in a range of Microsoft products, including Word, PowerPoint, and Outlook. When applied correctly, it can offer real-time accessibility-specific feedback. Furthermore, the Accessibility Checker can take a lot of pressure off educators when checking for accessibility and makes accessibility checking easier for everyone (Fichten et al., 2019). Educators can significantly reduce the work needed to ensure their content is accessible by actively screening in real-time. However, the Accessibility Checker does not spot all accessibility issues, for example, subjective meaning in links and headings means that incorrectly labelled links can go unnoticed. Therefore, educators need to be knowledgeable in accessible practice, even when these tools are available.

Educators must also be aware of all these practices which are more conducive to supporting accessibility. Educators also need to understand the application of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to scanned media and materials and how it aids a range of diverse learners. The OCR process converts an image of text into a machine-readable text format. OCR allows technologies to select and interact with individual words and characters within a document. The application of OCR can be highly beneficial to students using assistive technologies, including text-to-speech or screen reader software. A study of 143 students with low vision and 29 blind students noted how almost 90% of students who were blind and a third of those with low vision used scanning with OCR software (Fichten et al., 2009). The application of OCR is usually a quick process. However, it can depend on many factors, which include the quality of the original text, the font and spacing used, and the quantity of scanning required. The complexity of the content is also a factor, i.e., graphics, images, maths, and scientific notation.

As we move into a more mobile age for technology, new solutions are beginning to emerge. Students and educators no longer have to rely on large scanning devices to apply OCR across media and materials. Microsoft Applications, including Seeing AI and Lens provide a free, flexible, and mobile way to scan OCR documents and materials. While these apps are free, they often require a mobile hardware device to operate. The Lens app also allows users to open scanned documents in an ‘Immersive Reader’ view, a feature that allows for personal customisation and text-to-speech application. Other mobile apps also facilitate learner autonomy, for example, the free application Adobe Fill & Sign enables learners and educators to capture a picture of a paper form and fill it in digitally. This can provide access to a range of learners who struggle with traditional class workbooks and require technology to access the curriculum.

Table 1: Accessible Issues in Microsoft Word & PowerPoint

| Accessibility in Word & PowerPoint | Good Practice | Bad Practice | Accessibility Checker Detects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headings

|

Apply Styles in logical order – Helps Define structure | Bolded Headings, no structure | No |

| Alternative Text

|

Succinct and meaningful or decorative | Auto Description or use of ‘Picture of’ or ‘Image of’ | Yes |

| Link Descriptions

|

Describe link succinctly | Click here or a long address | No |

| Table Header & Merged Cells | Include Header and exclude Merged fields | Merged Fields & Missing Headers

|

Yes |

| Use of Colour | Use Colour Contrast Analyser & High contrast | Low Contrast, Emphasise with colour | Yes |

| Font Size and Type

|

Minimum 12 pt Sans Serif / 24 pt in PowerPoint | Commonly used Font 11 with Serif | No |

| Reading Order

(PowerPoint only)

|

Set Reading Order properly | Add content without checking the Reading Order | Yes |

PDFs are often a contentious point regarding accessibility (Fichten et al., 2009). The dilemma with PDFs is that their accessibility depends on how it was created. Ensuring PDFs are accessible can be difficult but providing a PDF with OCR already applied is a good start for those relying on text-to-speech. However, a PDF that has OCR is potentially inaccessible to a screen reader unless the PDF is tagged correctly. Each PDF tag identifies the type of content and stores some attributes (for example, paragraphs, headings, lists, and tables), creating a hierarchical tree structure within the document. The tag tree forms the logical reading order structure making the document easier to access and navigate. However, tagging PDFs can be a time-consuming and arduous task.

There are a range of free applications for OCRing PDFs that exist; some are web-based others come in the form of a free feature in paid tools like Adobe Pro or literacy software including Read & Write or ClaroRead. Microsoft’s Edge Browser with Windows 10 and 11 allows learners and educators to open PDFs, although it does not apply OCR to inaccessible documents. However, Edge empowers learners to read OCR’d PDF documents using text-to-speech and offers them various editing features.

Creating accessible media and materials can sometimes be laborious and costly. One example is the creation of transcripts and captions for video and audio content. Mainstream applications like Microsoft Stream and YouTube offer this auto-captioning service, including post-editing solutions. However, the accuracy of the original auto-caption dictates the amount of time needed to edit the captions. Unfortunately, auto-captions are limited and often depend on factors which include the microphone’s quality, the speaker’s voice, and the content. Significantly, the time taken to edit the captions may often exceed the time required to create the original video/audio content. However, tools exist that provide real-time human-based captioning solutions. These real-time human-based captioning solutions are often complex for students who need captioning services. The cost and logistics issues of acquiring a stenographer can be challenging. These stenographers/captioners can integrate within common online platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams (organised through the meeting administrator settings). However, they can also operate through third-party software for face-to-face interactions.

Newer paid solutions like Caption.Ed software by CareScribe allows for a more mainstream and flexible approach to real-time captioning while supporting several international voices. Despite using auto-captions, this software has quite a high accuracy rate and can be applied to any audio or video content on your device. It also provides a transcript in conjunction with the captions and therefore provides for real-time classroom notes. While this may provide a real-time, time-efficient solution, it is a subscription service which also requires some financial outlay. Caption.Ed also supports a range of different languages. Another tool, OtterAI, also works on a similar premise and may be more financially viable, it has a monthly subscription, and it also has a free version. It can also provide a transcript of the captions.

For shorter video content, apps, including Clips (free) and Clipomatic (paid), can offer quick video creation with editable captioning options. There are also post-production human-generated captions solutions. These solutions are often expensive and outside the budget of most schools. Companies like Cielo24 and Rev offer these solutions to allow educators to upload content to the cloud and receive back caption files within 12-72hrs. They also support translated captions and a range of standard file types like SRT or WEBVTT. However, for these solutions, the quicker the turnaround, the more expensive the cost. Ultimately, utilising captioning services that require time-sensitive approaches requires significant financial outlay from educational institutions. The alternative is a time-consuming process where educators must manually edit the auto-captions. However, a new captions-based solution is becoming mainstream in the form of Live Captions for Windows 11. Live Captions will allow all captions to be automatically generated from any audio content. Live Captions will also allow the captions box to float in a window or be exhibited at the top or bottom of a screen.

Although this is one of the newer accessibility features inbuilt in Windows, the inbuilt accessibility features across the main operating systems like ChromeOS, iOS, macOS, Windows and Android devices are continually improving. Accessibility and assistive technology features now come almost as standard with new appliances. These features include text-to-speech (for example, iOS Speak Screen, Safari Reader, Immersive Reader), speech-to-text (for example, Dictate, Google Voice Typing), voice assistants (for example, Siri, Alexa, Cortana, Google Home), screen readers (for exmaple, NVDA, VoiceOver, Narrator), screen magnification, contrast customisation including dark mode and night light. Moreover, a range of additional tools and features exist within the accessibility and access settings of almost every well-known operating system.

Another method for supporting accessible content is the creation of braille. Braille is a tactile writing system used by people who are blind or who have low vision. Despite the well-documented value of braille literacy, braille literacy is declining (Hoskin et al., 2022). From an education perspective, there is also a low incidence of learners who read braille in schools (Herzberg & Stough, 2007). Moreover, braille production requires specialised technologies, which are unavailable to many if not most schools. As a result, the production of braille in schools is often the remit of organisations set up to support students who are blind or who have low vision. Euroblind provides information on access to these resources in each country within continental Europe. To produce braille, educators or learners usually need access to a braille embosser. Braille embossers emboss braille characters onto paper for tactile reading. Before the braille can be printed, the device attached to the embosser must perform braille translation from text. This translation occurs through specialised braille software such as the Duxbury Braille Translator. This software supports over 170 languages, and it supports literary, mathematics, and technical braille. However, produced braille texts are often quite bulky and regularly need to be divided up into more manageable volumes.

Electronic texts are more transportable and less burdensome than these large braille volumes (Suzor et al., 2008). As a result, more people who are blind or have low vision are moving towards technology-driven braille solutions. Hoskin et al. (2022) agree, claiming that many braille readers also use technology such as refreshable braille displays to access braille. These braille displays provide access to data on a computer screen by electronically raising and lowering different combinations of pins in braille cells. They can show up to 80 characters from the screen, which refresh as the cursor moves around the screen. Braille displays have their advantages over traditional braille by allowing for a more practical solution for the digital age that engages more readily with electronic-based reading environments (Russomanno et al., 2015).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital solutions provided access for those requiring remote sign language interpreting. This remote approach was seen by many as a flexible and efficient way to facilitate sign language interpreting services (De Meulder & Haualand, 2021). Interestingly, this practice is still being employed in educational settings today. However, to enable more inclusive access to media, educators need to understand how best to support remote sign language interpreting services, for example, the Center for Excellence in Universal Design states a list of directions and techniques to ensure an interpreter is easy to see and read (National Disability Authority, 2022). These include capturing the entire signing space and ensuring the signer is the required size and visibility. Moreover, the provision of content-specific terminology for the interpreters before the class is essential and reduces the potential for complex translations.

Another accessible solution centres on the growth in audiobooks and text-to-speech-based solutions. Audiobooks can support a range of diverse learners, and it has been shown to improve language and reader competence while also increasing school performance, attitude, and motivation (Alcantud-Díaz & Gregori-Signes, 2014; Milani et al., 2009; Padberg-Schmitt, 2020; Whittingham et al., 2012). Free text-to-speech tools, including Balabolka, can create audiobooks, but professional audiobooks are also available through Bookshare and professional services like Amazon’s Audible. Available in many countries, Bookshare is an accessible digital library for all people with print disabilities. Unfortunately, Bookshare is only available for individuals with a qualifying reading or perceptual disability, a visual impairment, or a physical disability affecting their ability to read printed works. The Bookshare library, which supports over 34 languages, has over a million titles, including books for schools has the largest collection of accessible digital books in the world.

Alternatively, Amazon’s Audible is an online audiobook and podcast service that allows users to purchase and stream audiobooks. This platform will enable users to download and stream content from Audible’s substantial online database of audiobooks and podcasts. Similar to Bookshare, Audible utilises professional human voices to narrate its products. However, it is limited in terms of educational material. Audible can also be synced with Kindle to provide a human spoken text-to-speech with highlighting known as WhisperSync. For flexibility and to support different learners, WhisperSync lets users readily switch between reading the text and narration. While time can be a barrier to providing accessible solutions like captioning, there are additional barriers to creating accessible content.

Barriers and Solutions

There are many barriers and challenges that educators can face when promoting accessible media and materials in their classrooms. These barriers, in addition to time, include cost, knowledge, and other social factors, including stigma.

Finance and sustainability solutions are high priorities in most of today’s schools. However, accessible technologies, including many assistive technologies, invariably come with a high price tag (King & Allen, 2018). This high cost can deter schools and educators from utilising assistive and accessible technologies. Additionally, in many low-income countries funding may not be available to ensure access, and even less so in rural areas within the countries (Gulati, 2008). However, inbuilt accessibility and assistive technology features across most mainstream operating systems and applications may alleviate some of this cost associated with procuring assistive technology. Assistive technology freeware and open-source technologies also provide alternative options instead of expensive bespoke technologies. Many of the technologies available also have a free version, which in some cases may not be as effective. Trialling examples include Inspiration , Read & Write and LightKey. However, these free versions allow for the trialling of technologies to test their effectiveness. Therefore, educators can experiment with a program to see if it meets the needs of learners before investing in expensive technology that may not be suitable.

Another significant barrier throughout much of the literature is the time required to learn and support these technologies (Ault et al., 2013; Courduff et al., 2016; Flanagan et al., 2013). However, time does not only impact on these inclusive technologies, as many educators do not have enough time to explore, experiment, research and implement mainstream educational technologies (Khlaif et al., 2021; Polly et al., 2020;). Priority must be given to inclusive technology across teacher education, from pre-service and in-service training to whole-school approaches to inclusive education. This may alleviate some of the time concerns noted in adopting and understanding these technologies.

Learner barriers are also an issue for educators. Stigma can prevent people from using accessible or assistive technologies and accessible media and materials by garnering unwanted attention (Zapf et al., 2015). Learners who experience learning disabilities can feel ashamed about their learning difficulties. The stigma may not emanate from an individual learner’s functional limitations but from societal and social responses to disability. In that respect, stigma is caused by framing the conversation around disability, accessibility, diversity and not the use of technology itself. As a result, young people using specific adaptive technologies might feel that this makes them different to their peers, and additionally, their peers may see them as ‘other’ (Barbareschi et al., 2021; McNicholl et al., 2023).

Integrating accessible technologies into daily school life creates a new norm and reduces the stigma attached to these technologies, for example, smartphones either come equipped or require the download of applications which allow them to support reading, writing and organisation, text-to-speech, and dictation technologies. Having these technologies in a device everyone uses may hide the fact that the learner relies on a particular tool. Moreover, if assistive technologies like these mentioned above are used by many people using the same device, this can significantly reduce the stigma. Interestingly, newer mainstream technologies that support assistive technologies and accessible practices are already perceived to be more acceptable in this regard (Ok & Rao, 2017). The mainstreaming of assistive technologies across Microsoft applications under the umbrella of inclusion for all learners may further reduce the stigma associated with such tools.

Support for assistive technology and its implementation are known barriers to access for some learners (Ault et al., 2013; Bell et al., 2010; Donne & Hansen, 2016). Educators are often inadequately equipped to consider and implement the types of support (Naraian & Surabian, 2014). Moreover, keeping abreast of these changes can also be daunting and overwhelming for many educators (Dawson et al., 2016). The number of technologies available and changes in accessible practice can significantly impact educators and therefore emphasises the need for hands-on teacher training on accessibility tools, and technologies, for both initial teacher education and through lifelong learning and continuous professional development (Alkahtani, 2013; King & Allen, 2018; Michaels & McDermott, 2003; Schaff, 2018; Van Laarhoven & Conderman, 2011). However, social media is another potential way for educators to upskill and stay alert to changes related to accessible practice. Many teacher networks are already utilising social media which can influence teaching and learning practices (Willems et al., 2018).

Many of the barriers related to accessibility discussed previously can be addressed through training or more open and inclusive approaches to supporting learners. Whole-school and whole-classroom approaches can also mitigate some of these concerns. However, knowledge and information sharing is key to an inclusive culture and creating an accessible environment for everyone. In addition to knowledge, adopting frameworks like the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework allows schools and educators to promote accessibility as a tool that supports everyone.

Accessibility and UDL

Accessibility and the provision of accessible media and materials complement more inclusive frameworks, including Universal Design for Learning (UDL). A full chapter also exists on UDL elsewhere in this book. An innate bond exists between UDL and accessibility, a relationship educators need to understand if they are to support more inclusive practice (O Shaughnessy, 2021). After all, a universal approach must be an approach that aims to cater for everyone, including those with accessibility needs. Moreover, assistive technologies make UDL more accessible, efficient, robust, and financially sustainable (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2017). While UDL is not a technology-based framework, the flexibility offered by technology-enhanced learning options means that technology often plays a significant role in implementing UDL practices. By combining technology and UDL, schools can deliver more profound, accessible, and engaging learning environments for everyone, including those with diverse learning needs (Rose & Meyer, 2002). However, there is still a need for Initial Teacher Education programmes to emphasise UDL, instructional practices, and technology-enhanced pedagogy (Basham et al., 2010).

A UDL-based approach also creates opportunities to address potential accessibility-related issues (Al-Azawei et al., 2016; Zorec et al., 2022). Importantly, UDL emphasises both the accessibility of learning and the accessibility of educational material (Scott et al., 2015; Tobin, 2014). The application of accessible practice across the UDL framework is evident, for example, guaranteeing that teaching materials are usable, structured, and accessible is pivotal in promoting the UDL representation principle (Boothe et al., 2018). This approach ensures that all learners, including those using assistive technology, have access to the necessary materials. Nieves et al. (2019) also note how the UDL principle of action and expression facilitates accessible options for demonstrating learning and knowledge expression. By supporting learners with accessible content and using accessible systems, educators can support learner autonomy and paths that promote self-directed learning. Through regarding multiple means of engagement, accessible, and assistive technology tools can support and foster collaboration, facilitate coping skills and provide a range of options to minimise threats and distractions.

Adopting a UDL approach for educators, schools or institutions can sometimes be intimidating. However, the key to success can reside in taking a small-steps approach. By starting small, the UDL process becomes more manageable, and educators reduce the risk of becoming overwhelmed (Boothe et al., 2018; Novak & Rose, 2016). Tobin and Behling (2018) promote a similar approach called ‘Plus One’, a process that advocates adding one small thing each time along your UDL journey. O’Shaughnessy (2021) posits that an increased focus on accessibility can be that ‘Plus One’ or that first small step in an educator’s UDL journey. However, when introducing UDL, planning for accessibility needs to happen from the outset due to difficulties that often come from trying to retrofit UDL, for example, using accessible templates in PowerPoint increases the accessibility of the slides, this saves time and effort in trying to edit slides for accessibility afterwards.

Educator Awareness of Accessibility & School Culture

While designing from the outset may not always be possible, schools and educators can take steps to ensure staff are aware of tools and technologies to make lessons more exciting and grant better access to more learners. This section discusses two approaches: training for educators and communities of practice.

In terms of inclusive education, assistive technology and accessibility training must be included in Initial Teacher Education (Drelick, 2022). However, there is a need to address assistive technology and accessibility across all facets of the teacher education continuum. This need is reflected in the CPD needs of educators, where technology and special education needs loom high on the list of teacher priorities (Murphy & De Paor, 2017). Moreover, educators need to stay abreast of new approaches to instruction to meet the demands of today’s classroom (Thurlings & den Brok, 2018). Training for educators on accessibility should include practical tips and solutions with simple strategies for integrating within the classroom. Hands-on training should enable educators to experiment and become comfortable accessing, creating, and using accessible materials. Training should include giving educators guidelines to critically select and evaluate the available media and materials regarding the relevance for their learners and the topic at hand. To encourage and promote more accessible practice in schools, the development of a more cooperative peer learning approach is proposed in the form of a Community of Practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Communities of Practice have the potential to provide educators with information about the use of accessible media and materials (Lewthwaite & Sloan, 2016; O Shaughnessy, 2021). Their cooperative approach facilitates the dissemination of knowledge and personal experience, which can be highly beneficial in education. Educator Steven Anderson states on Twitter that “alone we’re smart, but together we’re brilliant” which captures the essence of communities of practice and their potential role in education (Anderson, 2013). Belonging to a group, using whatever means, be it in person or virtual, via some shared social space enables educators to create connections and discuss common issues surrounding the accessibility and use of media and materials. They also provide options for reflective practice, assessment, and ways to enhance student engagement (O’Shaughnessy, 2021). Establishing what worked for a colleague and what should be avoided can save a lot of time for educators. Moreover, these communities can play an integral role in the professional growth of educators (O’Sullivan, 2008).

A Community of Practice is just one approach that can benefit educators in promoting an inclusive agenda regarding accessibility. The whole-school approach to inclusive practice demands that senior management take proactive steps to ensure educators’ continuous professional development through workshops and seminars. Accessibility begins with creating an inclusive school culture. In keeping with this inclusive school culture, principals and senior management must invest in school-wide licences for technology that will enable universal access to media and materials. These technologies can promote learner independence and reduce the need for individualised accommodations and differentiation while supporting a more UDL-based approach to education that empowers the learner. A shift in focus from educators to a whole-school approach supported by school management may impact the inclusive culture within a school.

Principals also play a pivotal role in fostering inclusive schools (DeMatthews et al., 2021). This influence can be even more critical because educators may sometimes not know the right course of action when promoting inclusive education (Spratt & Florian, 2015). Communities of Practice and buy-in from senior management are vital components of inclusive culture in schools. Teotia (2018) argues that an inclusive culture’s diversity and unique perspectives enhance the school community including parent-teacher perspectives. Through the lens of the parent-teacher perspective, it is important for educators to be sensitive to the parents, as they can play an important role in inclusive education (Mann & Gilmour, 2021). Parents can create a platform that they can use to support each other and support their learners and their use of technology. Parents’ communication platforms support communication from schools regarding the progress of their child, school meetings, homework, and important notifications. Additionally, parents can communicate with each other on common issues that affect them. Communication and sharing are integral to inclusive school culture and promoting accessible practices. Inclusive cultures empower stakeholders, drive inclusive change, and break down barriers. Communities of practice, school management, and other stakeholders each play their own part in driving an inclusive agenda that supports and fosters accessible practice.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this chapter highlights the importance placed on educators providing accessible media and materials. The advantages of accessible practice, while essential for access and the promotion of learner autonomy, benefit far more learners. Moreover, while technologies including screen readers, speech-to-text and text-to-speech require material to be accessible, creating an accessible structure behind accessible media and materials makes it more engaging and navigable to every learner.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- How could you make the media you create daily more accessible?

- What tools could you integrate into your classroom to make your media and materials more accessible?

- Describe the communities of practice (COP) you already engage in which enhance your practice in accessible media and materials.

- How could you improve these communities of practice so that they operate more effectively?

- If you do not have any communities of practice which enhance your practice in accessible media and materials, how can you establish these? Think of COPs among staff, parents, learners, etc.