Section 4: Fostering Student Well-Being and Emotional Health

Being Afraid of ‘The Other’ – Phobias in Education

Anna Frizzarin; Damini Sharma; Jean Karl Grech; and Valerio Ferrero

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

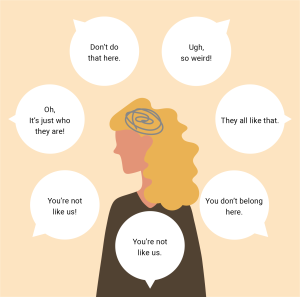

Figure 1: Example case.

Take some time to look at Figure 1 above. It depicts an unknown person who is receiving the comments displayed around them. You may notice that these comments do not specify an identity but mainly are using words such as “you” and “we”, or “us” and “them”. This is being done so that you, our reader, firstly reflect on who you think this individual could be and secondly to think about the emotions that they may be feeling as they hear them. As a teacher in training, it would be also beneficial to reflect on this scenario taking place in a school environment and apply the same two questions to this context. We suggest that you list or write both the identities and feelings you think of, so that you can refer to them as you read this chapter.

Take some time to look at Figure 1 above. It depicts an unknown person who is receiving the comments displayed around them. You may notice that these comments do not specify an identity but mainly are using words such as “you” and “we”, or “us” and “them”. This is being done so that you, our reader, firstly reflect on who you think this individual could be and secondly to think about the emotions that they may be feeling as they hear them. As a teacher in training, it would be also beneficial to reflect on this scenario taking place in a school environment and apply the same two questions to this context. We suggest that you list or write both the identities and feelings you think of, so that you can refer to them as you read this chapter.

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- Who is “the other”? How do you construct “the other”?

- What are the emotions at play, in the process of (re)producing othering?

- How does othering manifest itself in schools?

- What can teachers do to counter othering processes in their classrooms/schools?

Introduction to Topic

Difference, diversity and otherness are classic themes in education generally and specifically in teacher education. Schools, as key sites of interaction, are where individuals often encounter “the other” – i.e., those who differ from themselves in various ways. Teachers play a pivotal role in shaping these encounters, influencing how diversity is navigated and understood within a given classroom or school. The concept of “the other”, along with associated phobias, significantly impacts educational environments and the experiences of both students and educators. Phobias linked to race, sexuality, gender identity, and other dimensions of human diversity can foster climates of fear, exclusion, and discrimination in schools. In educational discourse, terms like xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, and Islamophobia are often used to describe specific forms of prejudices and discrimination. These phobias can trigger strong emotional reactions, and for those who are marginalised, the resulting discrimination can lead to feelings of fear, anxiety, shame, and social isolation. Consequently, addressing these issues is essential for creating inclusive, supportive educational environments where all students can thrive.

This is precisely why teacher education programmes should explore this topic beyond rhetoric. This means in the first place defining what otherness and diversity mean and understanding the experiences linked with them in educational environments. Various disciplines deal with this from a particular perspective: inclusive education, intercultural education, social psychology, cultural and educational anthropology, sociology, etc. However, given its extremely extensive and complex nature, defining the concept of “otherness” is a very complicated task and involves the examination of related and crucial notions like identity, difference, normality, culture, social order, etc. Therefore, interdisciplinary exchanges are necessary and allow us to go beyond simplistic explanations for overly complex phenomena whose understanding cannot be compartmentalised by a single disciplinary view (Morin, 2008). That is the reason why in this chapter we will refer to different theories and authors, trying to merge their perspectives in defining and addressing othering processes in education.

In doing so, this chapter focuses on the need to appreciate the uniqueness of each person without losing sight of the sameness that characterises us as persons. Our reflections concentrate on schools. Nonetheless, in every context there is an encounter between people with different baggage (Ainscow, 2016; Bernstein et al., 2020). An idea of unity (e.g., sharing a condition, a context, a perspective, a communicative code, etc.) and at the same time an idea of diversity (e.g., the different origins, biography, reference value system, etc.) are necessarily recalled (Granata, 2018). Unity and diversity are not antinomies, but dialectical polarities that are in constant dynamic relationship with each other (Granata, 2016; Ianes & Demo, 2023). Therefore, pedagogical action must take these two different and complementary dimensions into account. An excessive focus on the dimension of diversity runs the risk of forgetting the common humanity of people. Conversely, a strong focus on the dimension of human equality risks perpetuating an indifference to differences that can lead to inequalities, and a dynamic of exclusion and marginalisation.

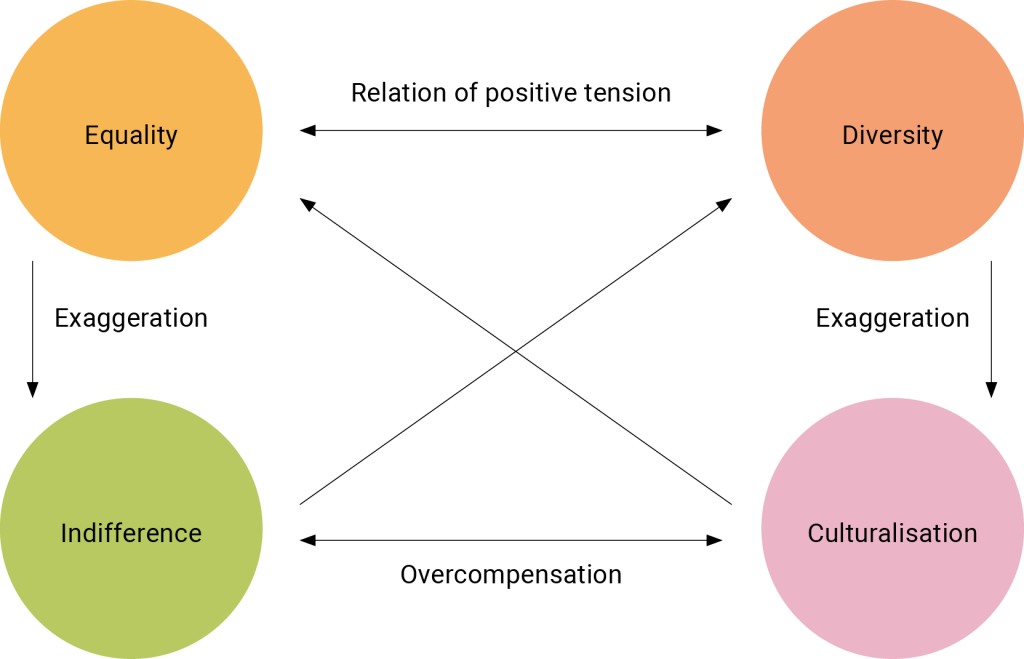

The dialectical model of cultural diversity elaborated by Ogay and Edelmann (2016) explains these dynamics and the resulting need to find a never-final balance between the dimensions of diversity and equality in order to highlight the uniqueness of each individual without falling into a dynamic of exclusion that is difficult to overcome (see Fig. 2). This elaboration refers specifically to cultural diversity, but we can imagine that the risk of culturalisation is present in any type of diversity, as will be explained throughout the chapter.

Figure 2: Dialectical model of diversity

In the following sections, we address this issue from a theoretical-practical perspective. Firstly, we examine the academic debate and the various theories that describe the processes of othering and their consequences for people’s lives, and in particular for their educational experience. Secondly, we focus on the emotions associated with othering, both from the perspective of those who perpetrate it and of those who experience it. Thirdly, we concentrate on school systems and schools, showing, on the one hand, how they produce and reproduce these phenomena and, on the other, how they can act to overcome them.

Key aspects

“The other” as a social construct

As you may have noticed from our example case, this chapter deals with the general concept of “the other”/otherness, without framing it in specific dimensions of diversity and/or groups. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, we are reflecting here a constructivist stance in the definition of otherness. This means understanding otherness as a social product emerging from the interactions among individuals and groups which, in turn, reflect power relations and dynamics present at the societal level. Within this framework, diversity and otherness are not fixed or given once and for all, but socially produced through socio-cultural practices and discourses (Wieworka, 2004). This, in turn, implies that they have nothing to do with the intrinsic characteristics of individuals, but rather on the meanings that are attributed to them in specific contexts (Goffman, 1968). It follows that “the other” can be considered as such only as far as he/she/they is/are perceived and identified as “different” by someone else. All this leads to the rejection of the idea of an ontological and/or biological foundation of diversity, which can instead be interpreted as the result of a relation involving certain individuals and their respective cultural systems and structures of signification (Burbules, 1996).

The process through which “the other” is “produced” in the sense we have just described is called othering. The term was originally coined within post-colonial theory, but the notion itself has deeper roots and draws on several philosophical and theoretical traditions coming from sociology, psychology and anthropology, amongst others. The concept of othering is used to describe the processes through which someone (usually the majority or dominant group) is ascribing difference or otherness to someone else or to some other group (usually the minority or non-dominant group) to categorise and form individuals’ and groups’ identities (Udah, 2019). Otherness is indeed an essential category of human thought, given that it is constitutive of the self: there must be the other for the self to exist and vice versa, and by defining self, one defines “the other” (Canales, 2000). This dichotomy, by putting emphasis on the differences between individuals and groups, is reflected in and based on a dualistic or binary thinking, which distinguishes and marks a border between self and other, us and them, ingroup and outgroup, and centre and margins (Brons, 2015; Dervin, 2012; Udah, 2019). This could for example be based on differences in terms of ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, language, ability, dress, religion or other characteristics. Specifically, people tend to emphasise “negatively” what differentiates them from others, in terms of some positive or desirable characteristic of the self or ingroup that “the other, /the outgroup, does not have. Conversely some negative or undesirable characteristic that “the other”, the outgroup, possesses and the self or ingroup does not (Crang, 1998, cited in Brons, 2015) is emphasised. Stereotypes and prejudices play a crucial role in such differentiations. In this way, both the identity of the self and of the others are constructed, but while the former is not defined by difference – but is rather recognised as “the norm”, or the standard to conform with – the latter comes to coincide with otherness, being often stereotyped and thus usually excluded or discriminated against (Canales, 2000).

All of this finally leads us to the second reason why, in principle, we are not referring in the current chapter to any specific diversity dimension: because we do not want to (re)produce othering processes by defining some individuals or groups as “the others” ourselves. Nevertheless, there will be examples in the text that refer to some specific groups and experiences: these must be understood as an attempt to raise awareness about exclusion and discrimination processes that need to be overcome, and not as an occasion to reinforce them.

Different forms/the roots of othering

As mentioned above, the concept of othering was first used by authors from the post-colonial, feminist and cultural studies to analyse “the lived experiences and oppressions of colonised, enslaved, marginalised, misrepresented and exploited people marked as Other” (Udah, 2019: 4). In the following section, we will provide examples of some of these authors’ analysis of different forms of othering to exemplify how such processes take place and can affect different identities or individual characteristics.

Post-colonial theory concerns itself with the study of the impact of colonialism on the colonised people and their societies. This suspected impact has been on language, politics, economy, and culture. In particular, language affects how people view and engage with the outside world: colonisers utilise language as a means of control and dominance to oppress the colonised. Within this framework, Gayatri Spivak first coined the term othering and used it systematically in her essay “The Rani of Sirmur” (Spivak, 1985) to describe how Europeans and Westerners have created differences between themselves as the norm and the others as inferior, using the example of the relationship between the British colonisers and Indian population. According to the author, the latter are silenced and denied their subjectivity through the dominant discourses, and thus relegated and forced into a position of inferiority and subalternity.

Similarly, in his writings on orientalism, Said (1979) explores how the Occidental scholars have built and portrayed the Orient (East) as barbarous, subpar, and strange to establish its inferiority and thus justify its colonisation, while reaffirming at the same time the cultural superiority of the West (Udah, 2019). According to the author, Occidental scholars indeed disregard the traditions, languages, and knowledge of the East and seek to justify colonial dominance via oppression and the need to “civilise” the local population. In this sense, the process of othering indeed upholds colonial legacies and strengthens societal hierarchies by not including the knowledge of the marginalised groups who do not appear to fit in and whose experiences are not valued (Young, 2009).

The same reasoning was used almost 30 years before by de Beauvoir ([1949] 2011) to describe how women have essentially been constructed as “the inessential other” by men to explain their subaltern position in society. According to the author, this is the result of a historical process of definition and mystification that ultimately relegated them to a position of inferiority and dependence on men. To put it in the author’s words, “she is determined and differentiated in relation to man, while he is not in relation to her; she is the inessential in front of the essential. He is the Subject; he is the Absolute. She is the Other” (de Beauvoir, 2011: 26). De Beauvoir’s notion of “the other” – understood as a social construct opposed to and therefore constitutive of the self – is the one upon which the concept of othering is based (Brons, 2015).

Foucault also examined this in the light of sex and sexuality, where he contested that “by the Age of Reason, what was involved was a regulated and polymorphous incitement to discourse” on the subject leading to a repressive understanding of the nature of sex, as a “genitally centred sexuality devoid of the fruitless pleasures” (Foucault, 1978: 34-36). The rise of science and medicine in the 18th and 19th century brought forth a focus on and development of terminology on the subject, which until then was devoid of language to distinguish it. This judiciary-medical rise of knowledge and discourse on the subject, referred to by Foucault as Bio-Power, had the capacity to categorise sex and sexuality into, ‘notions of “normal development” and “instinctual disturbances;” and it undertook to manage them’ (1978: 67). Thus, society became obsessed with eliminating the dangerous and perverse practices of sexuality through medical terminology.

These same processes are related to the cultural discrimination and social oppression often experienced by people with disability, as highlighted by Disability Studies and advocates for the disability rights movement. According to them, the category of disability stems from the dichotomy “abled” vs “non-/dis-abled”, based on a certain idea of the normal body and its functioning, both of which are socially constructed notions (Davis, 2013; Monceri, 2018). This is the result of a dominant discourse defined by the so-called medical-individual perspective (or “deficit model”), which considers disability as an internal characteristic of the person and sees a causal link between the individual impairment and being disabled. According to Medeghini (2010), this creates a condition of isolation for people with disabilities, by locating “the problem” within them instead of relating it to the possible causal role of contexts in the construction of disability.

Bourdieu’s theory of capital and social reproduction provides a critical lens through which to examine processes of othering and exclusion in society. He posited that different forms of capital – economic, cultural, and social – are not equally distributed, leading to the perpetuation of social inequalities (Bourdieu,1986). Cultural capital, in particular, plays a crucial role in this process. Bourdieu argued that educational institutions, while ostensibly meritocratic, actually serve to reproduce social hierarchies by valuing and rewarding forms of cultural capital possessed predominantly by the dominant classes (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). This unequal distribution of capital contributes to what Bourdieu termed “symbolic violence”; a form of non-physical violence manifested in the power differential between social groups. Bourdieu’s theory thus unveils the subtle mechanism through which social exclusion is perpetuated, challenging the notion of a truly meritocratic society and highlighting the deeply ingrained nature of social inequalities.

This is what happens in the caste system in India which, as analysed by Ambedkar in “The Annihilation of Caste”, provides an insight into “the other” within society (Ambedkar, [1936] 2022). Ambedkar’s concept of graded inequality illustrates how the caste system establishes a hierarchy where each group is superior to those below. The persistence of caste-based distinction leads to deeply entrenched discrimination in this form of social stratification. For instance; restricting access, participation and opportunities of individuals belonging to the lower castes especially Dalits. Students who belong to the lower structure of caste experience discrimination based on caste and are denied a share in the cultural and social capital of society (Sukumar, 2022).

As is evident from this overview, otherness and therefore othering processes are and can be linked to different individuals’ characteristics or identities and serve different “dominant” groups’ purposes by producing and reinforcing power dynamics and relations. Before describing how this is achieved, it is fundamental to highlight that some people may experience othering also on different levels because of their multiple identities. This is known as intersectionality. The concept has its origins in black feminism (Crenshaw, 2015; Hill Collins, 2019) and invites a multidimensional view of inequalities and discrimination: gender, geographic origin, religion, culture, sexual orientation, skin colour, education, socioeconomic status, age, nationality, (dis)ability are all dimensions that can add up and lead to inequalities and injustices that combine in unprecedented ways.

The construction of “the other”

As discussed above, othering is strongly hierarchical and lies on power dynamics between individuals and groups, as well as relationships of inclusion and exclusion (Canales 2000; Udah, 2019). However, one might ask at this point how othering is concretely achieved – i.e., how others’ otherness is defined – and how it manifests itself. It is indeed not enough for one individual to define another as “the other” to give rise to othering processes or, at the very least, to reach its most extreme consequences. This requires that practices and discourses related to otherness are shared and deemed legitimate within a given community. In this sense, the construction of “the other” is deeply rooted in power dynamics, discourse practices and knowledge production. This process is fundamental to understanding how social exclusion and discrimination operate within various contexts, including educational settings.

Power dynamics and exclusion

Those in positions of power, often representing dominant social groups, have the means to create and disseminate knowledge about themselves and those they regard as ‘the others’ (Foucault, 1980). This power allows them to shape the discourse by establishing power and reinforcing stereotypes about how society perceives other different groups. For instance, as seen above, Said’s Orientalism (1978) demonstrates how Western scholars constructed “the Orient” as backward, exotic and irrational, justifying colonial domination. Additionally, in line with Bourdieu’s (1984) concept of cultural capital, dominant groups maintain their power by valuing certain forms of knowledge and cultural practices over others. In Indian educational settings, this might manifest as curriculum choices that prioritise urban, upper caste perspectives, marginalising the experiences of rural, Dalit, and Adivasi communities (Nambissan & Rao, 2013). Those in power often have the means to widely disseminate their views through various platforms – social media, media, education systems, and cultural institutions. This influence shapes societal norms and values; often normalising the marginalisation of certain groups (Hall, 1997).

Power, discourse, and knowledge thus intertwine to create and maintain exclusion, discrimination, and othering in society. As Thomas-Olalde and Velho (2011) explain, drawing on Foucault and Laclau, “discourses produce subjects” (Thomas-Olalde & Velho, 2011: 35), shaping them through dominant narratives and power structures in society. These hegemonic discourses establish what is considered “normal” and construct distinctions between those who belong (the “inside”) and those who do not (the “outside”). Laclau’s concept of the “constitutive outside” is particularly relevant here. It suggests that powerful groups define themselves by creating “the other” – often marginalised groups, such as migrants or religious minorities. This process of othering is reinforced through various channels, including academic discourse, media, and public debate, which often present these groups as homogeneous and fundamentally different from the majority. For instance, the media representation of LGBTQI+ individuals can influence how they are perceived in society, which extends to educational institutions. McInroy and Craig’s (2015) research highlights this through their study of LGBTQI+ youth perspectives, where participants emphasise that media representations often reinforce problematic stereotypes. For example, transgender individuals are frequently portrayed as “sex workers, mentally ill… and as unlovable” (McInroy & Craig, 2015:607) or as individuals conforming to heteronormative gender expectations. The impact of these representations extends beyond media representations. The study found that over 20% of transgender individuals reported experiencing verbal harassment directly stemming from these media portrayals, with participants noting that negative media representations significantly influenced how they were treated in various social contexts, including educational settings (McInroy & Craig, 2015). These representations often reinforce existing stereotypes and contribute to the othering process.

This cycle of power, discourse, and knowledge production makes exclusionary practices seem natural and unquestionable, thereby maintaining existing power structures. By presenting certain perspectives as “factual and given” (Thomas-Olalde & Velho, 2011: 36), this system makes it challenging to recognise and confront discrimination and othering in society. In this way, the oppressor, holding societal power, can therefore reinforce their position by keeping “the other” away from centres of influence and decision-making (Freire, 1970). This exclusion prevents marginalised groups from challenging existing narratives or contributing to knowledge production, which results in perpetuating their otherness. In educational settings, for example, this implies that the dominant group’s culture and practices become the norm, which can make it difficult for marginalised students to feel included and can lead to their experiences and perspectives being overlooked or undervalued. For instance, history curricula often present a eurocentric perspective, while literature courses may feature few authors of colour. These omissions send powerful messages about whose knowledge and experiences are valued in society.

In this sense, power dynamics in educational settings – often mirroring broader societal hierarchies – play a crucial role in shaping students’ experiences and outcomes. Paulo Freire’s (1970) critique of the “banking model” of education highlights how traditional teaching methods can reinforce existing power structures. In this model, teachers are positioned as knowledge holders who deposit information into passive students, reflecting and perpetuating societal power imbalances. The content of curricula significantly contributes to these power dynamics. Stuart Hall in his work “Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices” conveys that cultural representation helps us understand how the systemic omission or misrepresentation of certain groups in educational material shapes societal perceptions and reinforces marginalisation (Hall,1997). For educators, understanding such power dynamics is therefore crucial. They shape not only the content of what is taught but also how it is taught and who has access to educational opportunities. As teachers navigate these complex dynamics, they must be aware of how their own positions of power can influence student experiences and outcomes, particularly for those from marginalised communities.

Among the various authors who have dealt with the processes of othering and the possibilities of overcoming them, bell hooks[1] (1994, 2003, 2010) is particularly noteworthy. This scholar and feminist has long emphasised the importance of looking at the dynamics of otherness, discrimination and racism from an intersectional perspective. Furthermore, she has emphasised that educational contexts are not neutral, but themselves produce and reproduce dynamics of inequality, dominant discourses and narratives, practises of subalternity and social exclusion. Only the construction of new narratives, the transformation of the classroom into a space of possibilities and the abandonment of transmissive modes in favour of dialogical and collaborative processes of knowledge construction, can promote marginalised voices and the awareness that there is not only one belonging, but multiple belongings that belong to us all. Education has a central role to play, but it too must be transformed from a decolonial perspective: diverse stories, narratives and experiences must be given a voice and space so that they can enter into a dialogue, so that pluralism is lived as a daily experience, in school and in society.

In this sense, intersectionality represents the key to interpreting educational and social contexts “in the plural”, taking into account all identity variables that can lead to exclusion and marginalisation due to their non-conformity with the dominant norm and the non-membership of subjects to dominant groups (Al-Faham et al., 2019; Cho et al., 2013). At the educational level, the intersectional approach shows us, on the one hand, the need to pay attention to all those aspects of identity and personality that can lead to exclusion due to their distance from dominant narrative and on the other hand, it emphasises that people are not monolithic but are composed of several variables that are mixed in a unique way. The encounter with “the other” thus becomes an opportunity for self-knowledge, for discovering “the other” within us and for overcoming all those cognitive, emotional, social and psychological barriers that produce othering processes.

Stereotypes, prejudice formation and discrimination

As mentioned above, the (collective) knowledge of “the other/s” promoted via dominant discourses is often based on negative representations and stereotypes about them (Brons, 2015; Udah, 2019). These are in turn incorporated in individuals’ social representations which influence their attitudes and behaviours, ultimately leading to the discrimination of those “othered”. In this sense, othering processes are fuelled by stereotypes and prejudices. In the following section, we will try to define these concepts and explain where they stem from – i.e., the psychological mechanisms behind them.

The formation of stereotypes and prejudices is often a result of the overgeneralisation of social categories. Stereotypes are general and often inaccurate beliefs about a group and serve as the cognitive foundation of prejudice. Allport (1979:191) defines stereotypes as “exaggerated belief(s) associated with a (social) category”. When internalised by society, these contribute to the formation of in-groups (those perceived as similar to oneself) and out-groups (those perceived as different or “other”). The theory of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) suggests that individuals belonging to the same social group (ethnic group, socio-economic class, caste, gender) naturally tend to favour members of their in-group over members of their out-group. The out-group perceives its “members as undifferentiated items in a unified social category, rather than in terms of their individual characteristics” (Tajfel & Turner, 1986: 279). This often leads to in-group favouritism and out-group discrimination. Hence, a stereotypical view of the out-group justifies discriminatory behaviour towards its members. In educational settings like schools, this process is evident in the formation of caste-based, class-based or language–based cliques, reinforcing existing social divisions. Research from educational settings indicates that educators often assume that students from the “dominant” groups hold the same views as fellow students from the “other” group (Garibay, 2015). This situation results in students feeling “othered”, like some form of difference from the norm.

Prejudice, instead, is defined as a “bias which devalues people because of their perceived membership of a social group” (Abrams, 2010:3). This bias can lead to negative attitudes towards out-groups based on stereotypes and has both cognitive and emotional components (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). The cognitive aspect involves the stereotypical beliefs about the out-group, while the emotional aspect involves an element of fear, uncertainty or anger towards them. These prejudices lead to discrimination, which is the unfair treatment of individuals based on their group membership. Prejudiced attitudes form ideologies and beliefs that justify discrimination (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995).

Members of privileged groups legitimise their position with positive regard of the in-group and negative regard of the out-group. This also applies to educational institutions like schools where teachers and/or students belonging to in-groups discriminate against students from out-groups. In an educational context, this might manifest as lower expectations for students from marginalised communities, leading to academic achievement gaps and social participation. For instance, teachers may unconsciously hold lower expectations for students with disabilities, which influences their participation and academic achievements in the classroom. Discrimination and isolation were found to result in increased school dropout rates, poor academic performance and impact on the mental health of students (D’Augelli et al., 2002; Kauffman & Landrum, 2012; Priest et al., 2014; Ruijs et al., 2010). Further research highlights that students who are discriminated against spend more time struggling with discrimination in the classroom instead of focusing on learning (Anjorin & Busari, 2023).

All of this shows how the concepts of othering and discrimination are deeply intertwined with emotional and psychological processes as they evoke a range of emotions and feelings, both in those who are othered and those who engage in othering.

What are the emotions at play, in the process of (re)producing othering?

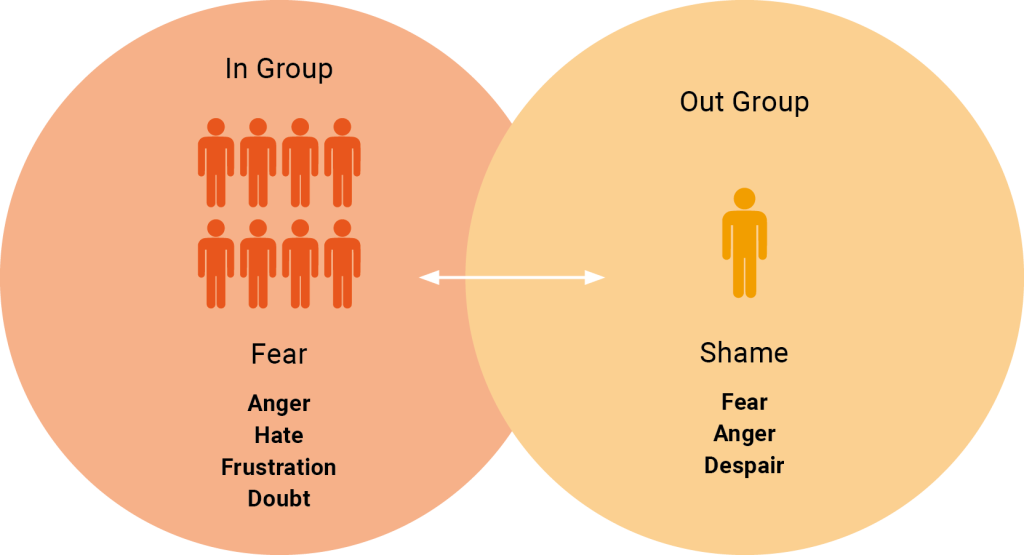

Figure 3: A depiction of some of the emotions at play in othering processes.

In the sections above we focused on the roles that knowledge and dominant discourse play for the majority to maintain power over those who are perceived as “the other.” We also elaborated on how this manifests itself in different forms of prejudice which are consolidated cognitively through beliefs and thoughts about the subject (i.e., internalised discourse and knowledge) and then manifested behaviourally (ie., through externalised action and expression of the former). This section focuses on the affective elements that are evoked in humans as they perpetrate and experience cognitive and, consequently, behavioural biases towards individuals and groups considered as “different others.” It further elaborates on the emotions that are at play in the process of categorising what is a part of “the us” and “the other” (Dovidio et al., 2010; Hovland & Rosenberg, 1960).

Ahmed (2004) explains how emotions are not just personal feelings, but are deeply intertwined with cultural and social contexts. Emotions shape and are shaped by the social norms, influencing identity and power structure between those constructing them and those abiding by them. This takes place through a continuous process caused by the nature of human relations, and the role that emotions play in the processes of socialisation and internalisation of the self in response to the reactions of everyone else. As Butler is quoted in Kahil (2017: 162),

For I am confounded by you, then you are already of me, and I am nowhere without you. I cannot muster the “we” except by finding the way in which I am tied to “you”!

Since there exists an inseparable and inevitable emotional connection between the individual and the social, the emotions of both those contributing to processes of marginalisation (in-group) and those who are othered (out-group) need to be considered here. Moreover, since the expression of these emotions is sometimes outwards, there is also an interplay between these two sets of emotions (see Fig. 3. This element exemplifies the capacity and power that emotions have at (re)producing constructions of othering. Figure 3 lists only a few of the emotions experienced, because literature suggests that these are at the core of establishing and maintaining power over individuals or different forms of minorities elaborated on above. This is especially the case for fear and shame, which are marked in colour in Figure 3 (Ahmed, 2004; Kahil, 2017). However, it is to be noted that there are other emotions which can be manifested in such interactions. This is why our example case asks our reader to list some of their own and we here once again encourage you to refer to them.

Fear & Hate

Fear is presented in both circles of our diagram because it is an emotion experienced by both groups. While the resultant impact of the emotion is common, that is to maintain and reproduce constructions of othering, it affects the people in the two circles differently. Focusing on the fear which is experienced by the in-group brings back to light the processes of negative stereotyping explained above (Dovidio et al., 2005: 7). The latter are needed because it is through these identifiable signifiers of a different “other” (object) that fear evokes itself as a consequential negative emotion. By establishing these characteristics as a threat, fear manifests itself in members of the in-group (Ahmed, 2004: 64). This requirement for an identifiable object to stir up aversion, through fear, is what comprises phobia. In fact, the same object being feared is often included as a prefix to the word “-phobia”. A subgroup of phobias is related to signifiers that make up the characteristics of an individual or a group within society. These include but are not limited to Islamophobia, anti-semitism, racism, ableism and queerphobia. Through such phobias, fear acts as a primary emotion which often triggers other emotions and also even mobilises the in-group to act on these. This, as history has repeatedly shown, results in mechanisms which seek to exclude and at times even exterminate feared figures who are perceived as a threat.

Following fear, other emotions then often manifest themselves in ways which further strengthen this divide, especially since these are directed toward the marginalised group, rather than being felt by the in-group witnessing a feared object’s approach (Ahmed, 2004: 66). Hatred is one of such key emotions. It is defined as a long lasting emotion involving bitter feelings usually towards a collective group and many times expressed in the face of “the other” (Smith & Mackie, 2005: 361). Hence, when it is expressed towards the out-group it directly impacts the individual witnessing and absorbing this emotion being thrown at them. In sum, while fear helps with classifying and establishing the threat, hatred is a resultant execution which directly impacts this threat through the distribution of various forms of violence. Anger and frustration are included in our diagram because these tend to play a similar and important role in intrinsically energising a population, which is trying to justify or make sense of the difficulties that they themselves may be experiencing. These are often the emotions that politics feed on to (re)produce power by locating the blame on a specific list of identities. Allport coins such type of hatred as character conditioned, whereby the individual thinks up some convenient victim and some good reason (Smith & Mackie, 2005: 362). An example of this in the context of schools is when “the other” is blamed for their inability to behave like the norm or for failing to catch up with their peers. This perception often fails to criticise the institutions which are failing to address the needs of both the student and provide the right support. This can often cause frustration which further propagates and strengthens the parameters through which the individual is perceived as “the other”.

On the other hand, the fear experienced by the “the other” is a consequential and reactionary emotion. The fear felt by those in the out-group is a reaction to the hate or other negative emotions thrown at them for failing to conform and thus of being excluded. Naturally, this further legitimises centres of normalised majorities and margins of minorities to which people respectively belong. As the minority succumbs to the feelings of being othered, it strengthens the power of those establishing the norms and practices for belonging. Unless contested, this fear experienced by “the other” manifests itself in different spaces in the form of active silence. Active silence refers to the deliberate, conscious choice of avoiding the subject and often it has the loudest voice in its impact (Humphry, 2012: 484). This is so because it further strengthens the visibility of the majority against the invisibility of “the othered” groups.

This pathologizing and repressive interaction between the two groups leads to dominant discourses not being contested by the opposing experiences of the silent other. Subsequently, inclusive, reparative and positive change fails to take place (Freire, 1970: 61). Kahil (2017: 135) suggests that such “pathologizing, repressing, excluding, and discounting the experiences of those othered within their own communities [have] a direct route to [the feeling of] shame”. In fact, shame is considered to be a leading emotion prompted by oppression and often it is said to hide itself behind other emotions including fear, anger or despair. This is why we will now delve further into this emotion.

Shame & Pride

“Shame is sensed as a result of a feeling of negation, which is taken on by the subject as a sign of its own failure, […] usually experienced before another” (Ahmed, 2004: 103). It is characterised by a threatened social image; Image Shame, or a threatened moral essence; Moral Shame (Allpress et al., 2014: 1270). Naturally this threatened image is based on the expectations and reactions of the same person or group in front of whom one is feeling shamed (the social). “The shaming targets any expression of subjectivity outside the boundaries of those ideals and is considered a trespass against the social” (Kahil, 2017: 138). The latter further affirms the location of both the in-group and the out-group since it requires a hierarchical system where the shamed is “the inferior” with the threatened image and “the superior” who is the one threatening the image of the other (Johnson, 2013: 90). In short, one cannot feel ashamed outside of a social interaction involving other people and the expectations established by them. It is experienced once the ego of the individual experiences a form of deviance from the norm which is pointed and even more so, if they are asked to change or address it.

Shame binds us to others in how we are affected by our failure to ‘live up to’ those others, a failure that must be witnessed, as well as be seen as temporary, in order to allow us to re-enter the family or community (Ahmed, 2004: 107).

On the other hand, this resultant feeling of shame is in itself a declaration of our interest, love and need to belong to the centre and not the marginalised other, according to Rula (2017: 138-139), which highlights the productive power that is contained within this emotion. In feeling shame, the self exposes its need for belonging with others and unless it contests this feeling, it submits to potential forms of oppression which decide who gets to belong and who does not. The latter is maintained through the established discourse and knowledge which distinguishes between the characteristics of the two parties. This sees the act of “colonisation” move away from the overt, physical and geographical colonisation of land and people, to “the colonisation of the psychic space” (Oliver, 2004: 43). This takes place when the psyche of the individual or group becomes colonised by that of the dominant individual or group through socialisation and the production of oppressive emotions.

The colonisation of psychic space is the occupation or invasion of social forces – values, traditions, laws, mores, institutions, ideals, stereotypes, etc. – that restrict or undermine the movement of bodily drives into signification…The psyche is the ‘place’ where bodily drives intersect with social forces (Oliver, 2004: 43).

Amidst all the emotions at play in this space, Kahil (2017: 135) explains how this colonising effect manifests itself mostly through shame because this emotion is expressed inwards, towards the self and not outwards. Other emotions such as melancholia and despair are then related to shame and likely to manifest since the subject takes on the “badness” as its own, by feeling bad about “failing” loved others.

We have so far mainly focused on the negative impact that emotions have in the process of othering, thus, picturing “the other” as a powerless individual absorbing and submitting themselves to this power. However, as we have seen throughout history, from different social movements, this is not always the case. The Black Lives Matter, MeToo and LGBT+ pride marches around the world are all recent examples of this. Pride and courage are also resultant emotions that stem from such experiences of shame. This is especially the case when these emotions experienced individually are spoken about, gathered and collectively raised by a marginalised group, through which, the same yearn for longing to a group, finds solace and energy in the experiences of more marginalised others. This emancipatory journey is deemed by Kahil (2017) as the productive face of shame.

Shame’s productivity stems from its capacity to motivate self-reflection on a lot of things, among which are the structures we take for granted, our complicity within such social structures and the validity of the norms/social codes we live by. (Kahil, 2017: 142)

Being able to question the established power structures and knowledge has the potential to lead the way towards emancipation. As the othered no longer confines themselves in fear and silence, powerful and normative discourse is challenged by that conceived as non-normative.

Having considered this productive face of shame, it is to be noted that sometimes, contesting and revolting against established structures and powers may not be an easy thing. Therefore, those choosing to be in silence and absorbing these negative emotions, may not necessarily be unaware of these structures or simply absorbing them. However, they can be in situations where they would be at greater loss if they had to speak up, especially if they do so on their own. Therefore, as Kahil (2017: 136) explains, “revolt ought to be accompanied by assurances that one will be forgiven by the same community or by an accepting/loving third”. Thus, if forgiveness is not possible, revolt may not necessarily manifest itself through major social movements calling for changes in communities. It can also be grasped individually by choosing to leave that community through migration.

All the structures and emotions at play described here are not new to the dynamics of the school culture. As a teacher in training, you, our reader, may be wondering as to how you can contest against experiences of othering that you witness in schools. The next section examines the different levels of people and stakeholders found in school communities and how they exert such colonising power and emotions on each other. After that, we try to provide some practical solutions and ways you can yourself challenge these structures.

Education systems and schools as (re)producers of othering processes

Othering processes often take shape in schools (Borrero et al., 2012; Canales, 2000; Wright, 2010). As shown by the several examples provided throughout the present chapter – educational contexts are indeed not neutral, but themselves produce and reproduce dynamics of inequality, dominant discourses and narratives, practices of subalternity and social exclusion. As such, as highlighted by Anjorin and Busari (2023: 3), “schools are cultural contexts that have the power and potential to promote students’ cultural assets or to ‘other’ youths in a way that keeps them from creating meaningful academic identities”.

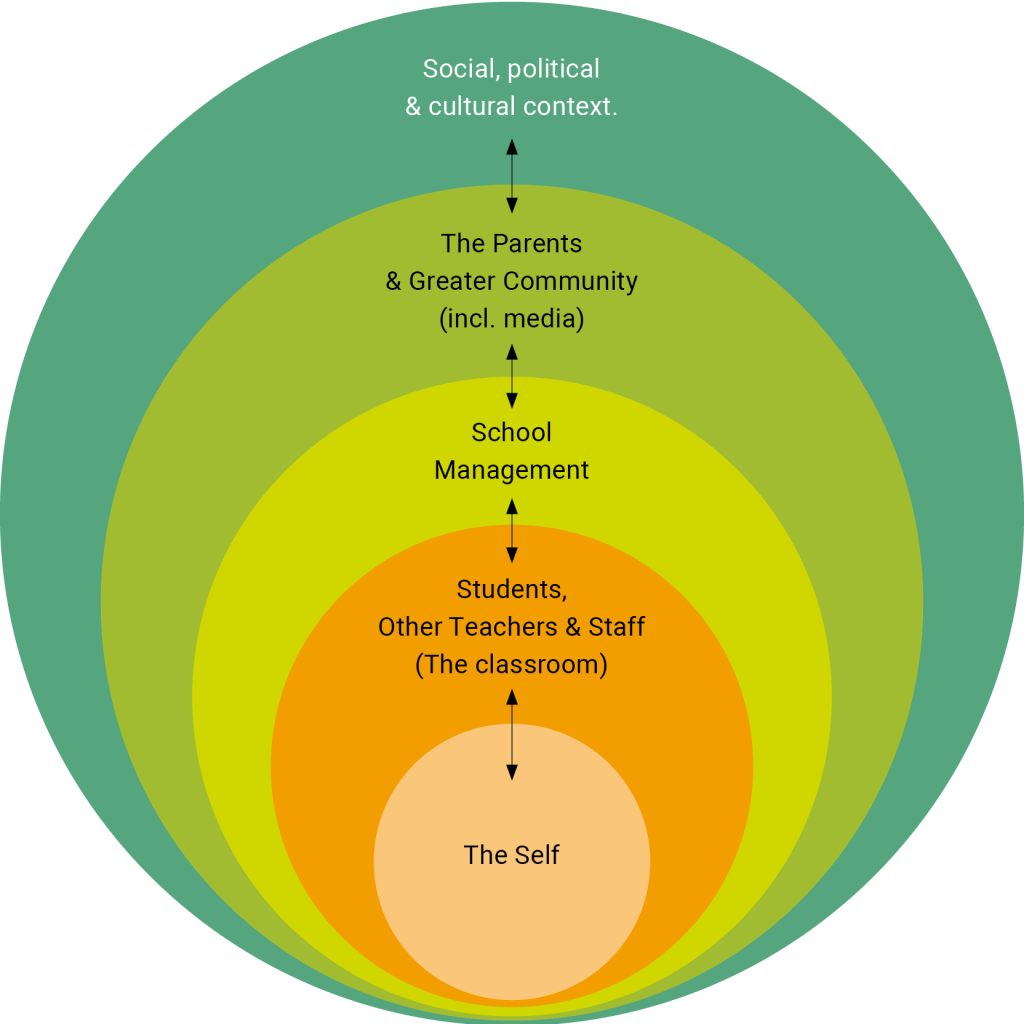

The search for the causes of such manifestations is a very complex undertaking, as various factors and actors come into play at different levels. Between structural and cultural aspects, we can distinguish the level of the self, the dynamics in the classroom, the decisions at the level of school governance and what is happening in the broader social and cultural context (Boeren, 2019; Ferrero, 2023), according to Brofenbrenner’s ecological-cultural model (1981; see Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Bronfenbrenner’s ecological-cultural model

Reflection on the dimension of the self is crucial and involves different actors: teachers, students, school leaders, families, etc. Within a kind of cognitive economy, each of us interprets the world through categories and schemas: we need to be aware of this dynamic in order to avoid developing stereotypes and prejudices that can lead to real discrimination and a compartmentalised understanding of reality. Going to school with stereotypical and prejudiced views runs the risk of othering processes (Brons, 2015; Dervin, 2012): based on a false and non-existent idea of the norm, certain groups of people are defined as different because they differ from the dominant group. This, as discussed above, creates real inequalities that have a major impact on pupils’ well-being and their chances of success at school.

At the level of the classroom, this means that the history and perspective of the country one lives in, and Western countries in general, take centre stage (Azada-Palacios, 2022; Bull & Alia, 2004): often there is no space for other visions and meanings, and everyone must conform to the dominant discourse. In many cases, the idea of co-construction of knowledge is not realised, instead we witness forms of cultural transmission where it is necessary to adapt to the thinking of the majority. This affects both the pedagogical relationship between teachers and students and the relationship between peers: the school culture (MacNeil et al., 2009; Roach & Kratochwill, 2004; Glover & Coleman, 2005) conveys a hierarchy in terms of languages, countries of origin, genders, social classes and many other dimensions, in turn conveying a colonial view that excludes those who are perceived as different.

The role of single school governance, in which teachers, head teachers, parents and sometimes students are entrusted with more institutional tasks, is also crucial. This is where rules and forms of organisation are established (Allen & Mintrom, 2010; Fullan, 1995): this is where a colonial, elitist school culture based on the idea of the norm can be changed. In fact, any attempt to approach homogeneity is artificial and doomed to failure (Dupriez et al., 2008): heterogeneity is a characteristic inherent to all social groups; creating situations of homogeneity in school means to be the bearer of a mindset that is not open to diversity and to the recognition that everyone has multiple belongings. Phenomena of school segregation and curricula that do not include histories other than the national one are two clear examples of how the institutional level can generate processes of othering with negative consequences for the educational pathway (Frankel & Volij, 2011; Watras, 2007).

Finally, the social, political and cultural context has a major impact on both school systems and individuals (Thomas-Olalde & Velho, 2011; Weiguo, 2015). When inequities exist at the structural level in terms of access to resources and social and civil rights, in terms of social norms and values, at the level of dominant policies and discourses, and when inequalities become institutionalised, a change on the part of the individual, but also, and more importantly, a paradigm shift involving policy makers and society as a whole is urgently needed. In this sense, individuals can play a crucial role in recognising forms of injustice and oppression and making their voices heard by the institutions that can change the social order (Hackman, 2005).

The dynamics we describe here are certainly complex and have been layered over the course of thousands of years of history. Therefore, it is difficult to unhinge the dominant discourses and practices of the subaltern, and there are no ready-made solutions. Yet, there is a lot that schools can do at each of these levels in order to counter othering processes. In the following section, we will provide some examples of how this can be concretely achieved.

Cultivating “the other” in us: the role of the school

If we think of the school context, work on the individual and professional self at the institutional level must be mediated through the dimension of collegiality (Bovbjerg, 2006; Shah, 2012). It is essential to promote self-awareness of groups in which positions of privilege or marginality can emerge that affect professional practice, in relationships with students and between teachers, in relationships with school leaders and families. Being aware of these dynamics is the first step to unhinge what produces processes of othering and inequalities in pedagogical action.

At the institutional level, it is important to develop educational policies that promote equity, inclusion, belonging and valuing the uniqueness of each individual (Karlsson et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2015). As also specified in Agenda 2030 (UN, 2015): the curriculum needs to be decolonised by giving importance to other languages, other histories and other narratives, giving voice to marginalised groups and those who cannot normally participate in decision-making processes, and imagining new forms of teaching and learning. This also has an impact on pedagogical practices in the classroom: from the transmissive model, we are moving to forms of teaching that typify active learning (Settles, 2012), where the student’s diverse and unique perspective is valued through dialogic and collaborative processes.

School systems, schools and all their actors can play an essential role at the policy level when it comes to activism and social change (Youdell, 2010). As teachers, principals, parents and students, we must have the courage to bring demands for equity and social justice to the public debate and to raise broad awareness of othering processes and all those groups that are excluded or marginalised because they bring some diversity to the dominant model (Apple, 2012). This political role of schools has been repeatedly emphasised by us and in other chapters: a pedagogical attention and awareness of the colonial mechanisms that characterise our societies is indispensable to promote diverse discourses and practises at every level (personal, classroom, institutional and political) against dominant thinking and to go beyond the classification “us/them” in order to be able to cultivate “the other” in all of us.

Practical implications

Focusing on the school and classroom level, the literature offers several approaches and strategies that teachers can apply to create inclusive learning environments valuing each individual’s identity/identities and promoting equity, inclusion, belonging for all. With a view to counteracting othering and its consequent forms of marginalisation in educational settings, we deem three of these as particularly important: (1) culturally responsive teaching; (2) anti-bias education; and (3) pedagogy of coming out (see Table 1).

Table 1: A summary of the three practical implications

| Culturally Responsive Teaching | Anti-Bias Education | Pedagogy of Coming Out |

|---|---|---|

| Requires educators to develop cultural competence through self-reflection, curriculum diversification, and support for linguistic diversity to promote belonging.

|

Helps students understand and build positive relationships with difference by creating learning environments that acknowledge and celebrate students’ different identities and encourage them to recognise and confront discrimination and inequities stemming from them. | Adopts notions of coming out to allow students and all those involved in the classroom to present their true authentic self rather than a conforming self. |

Firstly, as mentioned above, this implies a decolonisation of the curriculum so as to value different languages, histories and narratives, including those of usually marginalised groups. In this respect, culturally responsive teaching emerges as a powerful approach to address issues of othering and promoting belonging in educational settings. As Ladson-Billings (1995: 17) notes, it is a pedagogy that “empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes”. However, this observation underscores the critical role that educators play in fostering an inclusive environment that promotes belonging for all students. Instead, this pedagogical approach recognises and values students’ cultural references in all aspects of learning, creating inclusive spaces where everyone feels valued and respected (Gay, 2000, 2002). In this way, educators can create learning environments that not only address othering but actively promote a sense of belonging for all students.

To effectively implement culturally responsive teaching, teacher education programs should focus on developing cultural competence among pre-service teachers. Firstly, self-reflection is crucial. Educators must understand their own cultural background, biases, and assumptions. Ladson-Billings (1995) suggests that teachers engage in exercises that explore their cultural identity and how it influences their teaching practices. This self-awareness is the first step in recognising and addressing instances of othering in the classroom. Secondly, curriculum diversification is essential. Teachers should be trained to critically examine and diversify their curriculum to include perspectives from various cultural backgrounds. This might involve incorporating literature from diverse authors or using historical accounts that represent multiple cultural viewpoints. As Ladson-Billings (1995: 17) notes, “Culturally relevant teaching uses student culture in order to maintain it and to transcend the negative effects of the dominant culture”. By seeing their cultures reflected in the classroom, students from marginalised groups are less likely to feel othered or alienated. Addressing linguistic diversity is also crucial in creating inclusive environments. Teacher education should equip future educators with strategies to support linguistic learners, encourage the use of students’ home languages as resources for learning and promote the value of multilingualism. This approach not only supports academic achievement but also affirms students’ linguistic identities, countering language-based othering (García & Wei, 2013). Therefore, fostering belonging through culturally responsive teaching is not just about a welcoming atmosphere; it’s about fundamentally changing how we approach education to ensure that all students, regardless of their background, feel valued, respected and capable of success.

Alongside this decolonising effort, it is also important for teachers to actively address prejudices and discrimination in their classrooms and schools. The Anti-Bias Education (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2019) approach could provide a useful framework in this regard. Anti-bias Education aims to create learning environments accepting, understanding and celebrating students’ differences (i.e., different identities) while acknowledging and tackling the discrimination and inequities deriving from them (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010, 2019; Wagner, 2009). The approach requires teachers and students (and the whole school community) to identify and confront unfair and discriminating beliefs and behaviours. To do that, the approach proposes four lines of action (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2019):

- Building positive personal and social identities for all students (Goal 1: Identity);

- Enabling students to understand and build positive relationships with difference (Goal 2: Diversity);

- Developing students’ empathy, sense of justice, fairness and critical thinking, so that they will be able to recognise discrimination around them (Goal 3: Justice);

- Enable students to stand up against discrimination (Goal 4: Activism).

These four objectives should permeate all aspects of the school life and be reflected in the values and culture of the school, the curriculum, the teaching methods and materials used in the classroom, in the relationships among individuals within (but also beyond) the school, as well in its policies and activities, etc. In this way, students are likely to develop an inclusive mindset and develop the necessary knowledge, attitudes and skills to positively relate to and deal with “the other” also beyond the school walls.

Another way for teachers to address different forms of discrimination as the result of one’s identity/identities is constituted by the “pedagogy of coming out”. While the term “coming out” is mostly associated with the LGBTIQ+ community as they allow their identity to be shared with others, as a pedagogy in the classroom, this does not restrict itself to this one specific community. It is instead a teaching strategy which can be exercised by all those involved in the classroom. In essence it strives for visibility as opposed to the silencing of the individuals often experiencing othering. “It places [a primary focus] on the power and politics involved in the production of knowledge, and the political-economic circumstances of teaching and learning” (Pykett, 2009: 103), and contests it by making other forms of knowledge visible and accessible.

This pedagogy does not only address the exclusion of “the other” but also challenges the social location of “the normal” together with “the normal”, that is the majority itself. Therefore it is a pedagogy both for the oppressed and the oppressors. Freire’s (1970) work in “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” is instrumental to it because the author embraces such principles. The mere promotion of respect towards “the (different) other” in schools, falls in line with what Freire refers to as a ‘false charity, which constrains the fearful and subdued, the “rejects of life,” to extend their trembling hands,’ rather than ‘striving so that these hands … need be extended less and less [as] they become more human hands which … transform the world’ (1970: 19). Applying this to the subject discussed here implies that what a liberating pedagogy of coming out should do, is beyond only celebrating diverse identities. It should instead, provide the space for all humans to understand their unfinishedness and their potential to be othered in some shape or form and to allow for the critical self to transform reality, in the continuing process of the humanisation of all human beings. As a pedagogy it is mostly achieved during day-to-day life in the classroom, through authentic interaction with different realities of the lives that make up the community itself and the emotions that are at play. Authentic interaction for teachers with students, strives to let go of the soulless disseminator of knowledge and instead transforms into a being with their own story that can be shared. The latter is naturally evermore crucial if the teacher is a part of the othered minority. On the other hand, authentic learning and teaching for the student sees also transformation, as they no longer remain a lifeless vessel of content but instead an active participant in the formation of new knowledge. Students are encouraged to talk about their identities and experiences. These are used together with the classroom to build a community.

Through such a strategy, liberation no longer remains as another deposit to be made into men, but it is praxis, “the action and reflection of men and women upon their world in order to transform it” (Freire, 1970: 61).

These are of course just a few examples of ways through which teachers and educators can counteract othering processes in their classrooms and schools. In this handbook you will find several other possible approaches and strategies, addressing all the levels of the model depicted in Figure 4.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

We would now like to suggest some open questions for you to reflect on yourself as a person and as a pedagogical professional. Do not consider these questions as exhaustive, but as a possible opening for other questions to think critically about the processes of othering, the binary “us/them” categorisation and the need to engage in ways of decolonising our minds.

- Have you ever felt like “the other”? How did you feel? What feelings did you experience?

- Have you ever been in a situation in which you saw other people as different from you, in which you carried out othering processes? What attitudes did you adopt? What provoked them?

- Are there differences that you dislike less than others? And why?

- What can you do in the classroom to cultivate a culture of diversity that does not ghettoise, but unites, so that everyone discovers “the other” in us?

- What ideas could you bring to the leadership of your school to avoid othering processes and decolonise the school experience?

- How do you envision your political role?

Literature

- A pseudonym for Gloria Jean Watkins. The American scholar and activist chose it in reference to the name of her grandmother, Bell Blair Hooks. She decided that it should be written with lowercase initials so that the focus would be on the content of her writings and not on who she is. ↵