Section 4: Fostering Student Well-Being and Emotional Health

Sticks and Stones: Bullying and Microaggression at School

Clíona O'Keeffe; Evrim Çetinkaya Yıldız; Fatma Kurker; and Pamela February

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Below, we provide three example cases of people who have experienced bullying for various reasons. They describe a few of their experiences, and the chapter will refer to these cases throughout.

Example Case 1 – Sam

“I have experienced a lot of exclusion within school from age five up until about 16, 17 or potentially even 18. I was a really awkward kid. And I’m also trans (gender), so I was hanging out predominately with girls in school. I was always the kid that, they went, “Oh, we don’t want to be friends with her any longer. We don’t want to play with you, and we don’t want to be your friend anymore”. And I had that experience every year, all the way through my schooling. It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve realised I’m neurodivergent, and it explains for me quite a bit of what I had gone through. (I was probably the really awkward kid who was overly chatty). But then my peers basically decided that they didn’t want to associate with me any longer, and it became a very lonely space. I moved schools when I was 11 from a mixed school to an all-girls school. The reason I chose that all-girls school was that this school was a feeder school for the secondary school. So, actually the bullying continued and was quite an uncomfortable experience for me being a non-binary masculine person in an all-girls school.”

Sam Blanckensee, National University Maynooth Ireland, Ireland

Example Case 2 – Andrew

Bullied as a child

“My experience with bullying in schools. It happened in as early as grade one. You know, as a little boy, I was quite effeminate, but I was also very outspoken. And, you were told a lot to shut up. You know, the older you get, you realise shut up is not just verbal. It’s shut up physically. Shut up with your talent. Shut up with your gifts. Shut up with your ability. So that bullying for me, at a very early age, I realised it was shutting me down. Not just my voice, but my presence, my involvement, my inclusion. I would be told to shut up in the library, but I’d be shut up on the playground as well. And so you want to be kept silent. By the time I reached grade five, at age ten, I felt like they definitely didn’t want to see me at all. “Shut up” turned into “don’t be here”—they wanted me to disappear. It becomes a really, really strong exclusion. And then when I went to high school-grades seven, eight, nine, you realise you could feel it because you look around and realise, well, where’s everyone? And then you realise that you have been excluded, and that bullying came through the form of exclusion. Everyone is welcome but you. You get to realise that you are being excluded for reasons that sometimes you didn’t even understand. And that was something that I think bothered me when I got older, and I realised I was being bullied for things that I didn’t even understand. I remember, you know, being described as gay and all those strong words we used back in Jamaica for gay. At that time, I didn’t understand people what gay was. But you are being accused and labelled with those words, and it felt horrible. You know, I think we have to realise the impact that bullying has had on many of us. It was horrible.”

Bullied as an adult/a teacher

“The bullying is different because now it’s coming from outside of school. It’s coming from parents. And you kind of want to redefine what bullying is at that time because you wouldn’t think it was bullying. But those looks, the questions, the conversations that felt violent because, you know, we’re being questioned if it’s safe for you not only to be in school, but for children to be around you as a teacher. So it comes again with the assumptions, the stereotypes. And I can tell you for a fact that those assumptions and the stereotypes they follow you. It’s no longer the playground. I think a lot of the myth that I wanted to talk about is that we really think bullying is for just the classroom and the kids on the playground. Bullying is happening in the staff room in our schools. Bullying is happening in PTA meetings and parent council bullying is at every single level in our society. And it’s not just a school thing, it’s a people thing. When people are doing harm to each other. We bully and it’s harmful.”

Andrew B. Campbell, University of Toronto, Canada

Example 3 – Yuko

“To begin with, I have a brother who has a disability, and, although he’s physically okay, he cannot speak, and has intellectual impairment. When I was in elementary school, bullying started in the first grade. They imitated my brother’s voice or demeaned him in front of me to make fun of me and to make me feel really bad, but my family and I got through it. Although the adults also experienced discrimination as a family, we, collaboratively, encouraged each other. The bullying became severe at the age of 13, and, the whole classroom, became an enemy to me. They wanted to attack me. I got verbally, sometimes physically abused. They hid my shoes. They wrote graffiti, such as words like “die” or “get out” or “how is your brother doing?”, and so on, on my desk. I thought, I don’t have to erase the words using my eraser. They should. They should erase the words. So for four months, I didn’t do anything about the desk. Then, finally a classroom teacher noticed and he asked what happened to your desk? Did you write on it? I asked, why would I write this?” This is my desk. Then he realised that I was being bullied. But before that, nobody noticed. So the teacher wanted to improve the situation, but still the bullying went on after school when the teachers were not watching us. So at that time, I really felt I should get over it and one thing I saw as a strategy to survive was to study hard to defeat them, which I didn’t before. That’s really made me what I am today. And, of course, it was a blessing in disguise for me as it really enhanced and encouraged me. But it is difficult for all the people who are bullied in Japan to get over being bullied. Some killed themselves, and that’s happened a lot. Now that I have become a teacher, I really can relate to the students’ feelings, but I really didn’t want to share my own experience with them because I wanted to be away from my own hardship. So it was difficult for me to share my own feelings until only recently. I started to share my own experiences and found that the situation was better because sharing collaboratively felt great.”

Yuko Uesugi, Eikei University of Hiroshima, Japan

Note: For the sake of clarity for the reader, we have amended the direct transcript in the examples. For the exact words, please watch the full interview with Sam, Andrew and Yuko.

Initial questions

In this chapter, you will find the answers to the following questions:

- Who defines bullying and how?

- What are the different forms of bullying?

- What is the prevalence of bullying across different settings and contexts?

- What are the roles of those involved in a bullying situation?

- What is the motivation for and cause of bullying?

- Who to whom?

- What are the effects of bullying?

- Mechanisms of change: How can we prevent and address bullying in our schools?

Introduction to Topic

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me is an old rhyme, adage or proverb (the earliest seen around 1844), at times chanted by children who were taunted and teased. This chapter will prove that sometimes the pen (words) is mightier than the sword. King Solomon (Proverbs 18:21) stated that “Death and life are in the power of the tongue.” Or as the English comedian Eric Idle said: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will make me go in a corner and cry by myself for hours.”

If we asked the man in the street about their experiences concerning bullying, that is, whether they have been bullied or witnessed bullying, we would get a vast range of stories depending on who we asked. Their responses may also vary as to how to handle situations where bullying occurs, depending on these experiences. What will probably cut across all their experiences is how vividly they remember them, even if it happened way back in their childhood days. The three examples depicted above of Sam, Andrew and Yuko are cases in point.

The children’s rhyme referenced at the start of this chapter underscores that bullying has deep historical roots. First documented in 1844, this chant reveals that even 180 years later (in 2024), the concept of bullying is still widespread, complex, and often misunderstood. Despite the passage of time, confusion lingers, and efforts to address and prevent it continue as we seek effective strategies.

This chapter aims to unpack bullying as follows. The chapter starts by defining bullying and reflecting on who defines it. It looks at terms sometimes confused with bullying and the various forms bullying can take. We look at the concept of microaggression as a specific form of bullying. Based on our introductory remarks, bullying may regularly occur, but what do statistics say about its prevalence? We look at the roles of those involved in a situation where bullying occurs.

The chapter reviews theories of bullying and the related research carried out. We examine the motivation for and cause of bullying. We also scrutinise who is bullying whom. Furthermore, important aspects of the chapter are the effects of bullying on learners, the classroom, the school and the community as a whole. To mitigate these effects, the chapter examines the mechanisms of change, that is, what strategies could the learner, the classroom, the school and the broader community adopt?

This chapter is tailored towards student teachers who will come across situations where bullying occurs. The chapter poses questions throughout that are meant to make the student teacher reflect on bullying in relation to the learner, the classroom and the school community situation in which they find themselves.

Key aspects

What defines bullying, who are the individuals involved in bullying situations, and what are the different types of bullying?

Bullying can be interpreted differently. However, our aim in this section is not to focus on differences, but to develop a common understanding of the nature of bullying. With this understanding, we hope to help readers better understand bullying behaviour, be more sensitive to its detection, and develop effective intervention plans.

a. Bullying

One definition of bullying is “aggressive, goal-directed behaviour that harms another individual within the context of a power imbalance” (Volk et al., 2014). However, the most well-known definition of bullying is “being repeatedly subjected to harmful actions by one or more individuals” (Olweus, 1993). For this author, bullying is characterised by aggressive behaviour or intentional harm-doing, which occurs repeatedly and over time in an interpersonal relationship marked by a power imbalance. In addition to these two characteristics listed by Olweus (1993), power imbalance and harm are also among the characteristics of bullying (Volk et al., 2014). There are 4 key characteristics of bullying:

- Intentional: Bullying behaviours are intentional and driven by the intent to harm (Olweus, 2012). This characteristic distinguishes bullying from self-defence and reactive aggression. Bullying is not spontaneous or motivated by self-defence; it is carried out deliberately and with bad intention.

- Repetitive: Bullying is a repetitive behaviour and is not limited to a single incident. It occurs repeatedly over time (Olweus, 2012).

- Power Imbalance: A power imbalance exists between the parties involved in bullying, which can manifest in various forms, including physical, cognitive, and social power. Physical power refers to differences in strength or size, while cognitive power involves disparities in intellectual abilities, such as verbal fluency or social-cognitive skills. Social power arises from factors like popularity or social status (Volk et al., 2014).

- Harm: Bullying is harmful to those who are subjected to it. The harmfulness of bullying is the product of both the frequency and the perceived intensity of a behaviour (Harm = Frequency × Intensity) (Volk et al., 2014). In other words, as either frequency or intensity increases, harmfulness appears to increase as well (Ybarra et al., 2014). (Intensity examples: pinching (lower), stabbing (higher), etc.)

While there is no universally agreed-upon definition of bullying, a commonly accepted description emphasises its key characteristics: intentionality, repetitiveness, and the negative (unwanted or harmful) actions of one or more individuals directed at another person who cannot defend themselves. Bullying is often viewed as an aggressive act or deliberate harm that occurs repeatedly over time within an interpersonal relationship characterised by a perceived imbalance of power. A conflict cannot be considered bullying when both parties have equal strength. Therefore, in a school setting, teacher-targeted bullying is identified when a learner victimises a teacher who has authority over the learner, though the teacher may not use that power (Garrett, 2015).

Bullying is often confused with aggression, violence, conflict, and disputes. However, these behaviours have different characteristics.

b. Terms confused with bullying

Aggression: In social psychology, aggression is most commonly defined as a behaviour that is intended to harm another person who is motivated to avoid that harm (DeWall et al., 2012). This harm can be in various ways, including physical injury, emotional distress, or damage to social relationships. There are 4 key characteristics of aggression (Allen & Anderson, 2017):

- Aggression is an observable behaviour (not an aggressive thought or feeling).

- Aggressive behaviours are intentional and carry out the goal of harming another.

- Aggression involves people.

- Recipients of the aggression must be motivated to avoid harm.

Two characteristics that distinguish aggressive behaviour from bullying are repetition and power imbalances. Let us not to forget that not every aggressive behaviour constitutes bullying.

Violation: Violence is a risky behaviour characterised by intentional harm inflicted through physical or psychological means. This harm can be directed towards oneself, others, such as in student-on-student, student-on-teacher, teacher-on-teacher, or teacher-on-student scenarios, or objects (Steffgen, 2009). All violent behaviours can be considered as aggression, but not all aggressive behaviours can be considered violence (Allen & Anderson, 2017). Given that violence is characterised as an extreme manifestation of aggression (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010), it can be inferred that the distinction between aggression and bullying parallels the distinction between violence and bullying. This differentiation is mainly due to the repetitive nature of bullying and the presence of a power imbalance inherent in bullying situations.

Conflict: In its simplest definition, conflict refers to incompatibilities, disagreements, or dissonances within or between social entities (individuals, groups, institutions, etc.) (Rahim, 2002). There is a fundamental difference between conflict and bullying. From this perspective, two key aspects set bullying apart from conflict: (a) the perpetrator’s intention is not to resolve a mutual disagreement but rather to deliberately and actively harm the victim, and (b) the unequal power dynamic in which the perpetrators hold control over the victims due to a significant power advantage. This power imbalance is pre-existing and present from the onset of bullying. Perpetrators deliberately target victims based on this imbalance, choosing those who are weaker (Baillien et al., 2017; Keashly, 2020; Olweus, 1993). Despite the conceptual distinction between bullying and interpersonal conflict, the literature discusses the potential effectiveness of conflict management skills in reducing bullying in schools. However, studies have shown that there is no relationship between conflict management and bullying victimisation in schools (Burger, 2022). These findings highlight the need for distinct approaches when addressing bullying and conflict in educational settings.

Disputes: Disputes are short-term disagreements between people or groups (Burton, 1990). Two key aspects that set bullying apart from conflict also apply to disputes. In disputes, there is not always an imbalance of power between the parties, and there is no intention by the parties to deliberately and systematically harm each other. Disputes are more easily resolved than both bullying and conflict.

c. What forms can bullying take?

Examining the types of bullying can facilitate defining and intervening in bullying incidents. Therefore, this section provides explanations regarding the various forms of bullying behaviour.

Physical: In this form of bullying, the bully is directly involved in physical behaviours (Crick, 1996). Bullying that involves direct, physical, and obvious behaviours includes actions such as hitting, kicking, pushing, shoving around, locking someone indoors, damaging their belongings, or seizing or destroying others’ property as a means of intimidation (Crick, 1996; Gong et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2009). Physical bullying is a common type of bullying in schools, mainly due to the presence of individuals from various age groups in the school environment. Younger students who are behind in physical development are at higher risk for physical bullying (Crick, 1996).

Verbal: Bullying with cruel words involves hurtful name-calling, verbal abuse, ridicule, threatening, insulting nicknames, and spreading gossip or rumours, such as name-calling and teasing in a hurtful way, which refers to actively saying unfriendly words to harm, hurt, or scare others (Wang et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2024). Verbal attacks can be personal or sexual, or they may target the victim’s family, race, or religion (Sticks and Stones, n.d.). This type of bullying can occur in person, by phone, by email, or in other virtual environments. Due to its possibility to extend beyond the school environment and its insidious nature, it is more difficult to detect compared to physical bullying.

Relational: Relational bullying refers to an indirect form of bullying that “refers to the manipulation of social relationships to destroy or damage others’ social network or social reputation” (Gong et al., 2024, p.2) and includes social exclusion, such as being excluded from a group of friends or being ignored, and spreading rumours, including telling lies or spreading false information about someone (Wang et al., 2009). Although it has highly destructive effects on the bullied person, it is more difficult for others to notice and intervene. To better understand relational bullying in school environments, you can watch the 2004 movie “Mean Girls.“

Emotional: Emotional bullying is a type of bullying that targets a person’s emotional well-being, self-confidence, and self-esteem. It can manifest in non-verbal forms such as laughing, pointing, staring, or drawing pictures, as well as in psychological forms like isolation and rejection (Fried & Fried, 2004). Unlike physical or verbal bullying, emotional bullying does not involve direct physical contact or words, but rather focuses on disrupting the individual’s emotional state. Emotional bullying often overlaps with verbal and relational bullying, but its primary aim is to cause emotional harm through behaviours like constant criticism, blaming, emotional manipulation, and demeaning actions.

The types mentioned above are traditional forms of bullying, meaning they encompass all the characteristic elements of bullying behaviour (intentionality, repetition, power imbalance, and harm). In addition to these, there is cyberbullying, which has become a widely recognised concept in recent times. While cyberbullying is often evaluated as the online extension of traditional bullying, it also possesses its own distinct characteristics while still carrying the attributes of traditional bullying.

Cyberbullying: Cyberbullying can be defined as any behaviour performed through electronic or digital media by individuals or groups that repeatedly communicate hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort on others (Tokunaga, 2010). It can occur on social media, messaging, gaming, and mobile phones. Cyberbullying is a form of bullying that occurs through the use of digital technologies. This type of bullying involves repeated behaviours aimed at scaring, angering, or shaming those who are targeted. For example, spreading lies about someone or posting embarrassing photos or videos of them on social media, sending hurtful, abusive, or threatening messages, images, or videos via messaging platforms, or impersonating someone to send mean messages to others are all examples of cyberbullying. Face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying often occur alongside each other, but cyberbullying leaves a digital footprint—a record that can help stop the abuse (UNICEF, n.d.). The “Is Anyone Up?” website serves as a stark example of the severe consequences cyberbullying can have. This platform enabled targeted harassment and revenge porn, causing significant harm to individuals’ lives (Tallerico, 2022). It illustrates how cyberbullying can extend beyond individual actions, with its negative impacts spreading at the community level and reaching severe levels of harassment. This case underscores the need for legal regulations to combat cyberbullying, such as the Australian goverment’s Charlotte’s Law (Anti-Bullying Crusader, n.d.). Cyberbullying is distinguished by its feature of anonymity, which, along with a wide audience, increases the potential to harm victims. Unlike traditional bullying, where the victim knows the bully’s identity and witnesses their power display, cyberbullies remain anonymous, reducing their risk of being caught and encouraging more harmful behaviour. This anonymity can leave victims feeling powerless and inadequate. Moreover, cyberbullies often fail to grasp the consequences of their actions, leading to a lack of empathy and remorse. The public nature of cyberbullying further amplifies its impact, often resulting in more severe outcomes than traditional bullying (Slonje & Smith, 2008). You can find a cyberbullying case sample: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/06/technology/tiktok-fake-teachers-pennsylvania.html

There is also another classification that Smith (2016) suggested.

- Bullying based on disability

This type of bullying, often referred to as disability-based bullying, involves targeting individuals because of their physical or cognitive differences. This form of bullying can occur in various environments, including schools, workplaces, and online platforms. A study carried out by Aljabri, Bagadood, and Sulaimani (2023) addresses the significant issue of bullying experienced by learners with intellectual disabilities during their intermediate school years. Key findings from the study indicate that all participants reported being bullied, with the most common types being physical and verbal abuse, along with social isolation and ridicule. The emotional repercussions for these students included feelings of embarrassment, anger, and withdrawal, leading them to prefer associations with peers with disabilities over neurotypical students. In fact, students with intellectual disabilities often struggle with limited social skills, making them more vulnerable to bullying, which can result in decreased self-esteem and academic performance. The authors recommend promoting respect and appreciation for these students among neurotypical peers, encouraging active involvement from adults in fostering inclusive environments, and implementing peer support programs to enhance understanding and friendships. In conclusion, the study emphasises the necessity for schools to adopt proactive strategies to combat bullying and support the social integration of students with intellectual disabilities, ultimately aiming to create a safer and more inclusive school culture that benefits all students and promotes diversity and acceptance.

- Identity-based bullying

Identity-based bullying at school refers to harassment or discrimination that targets students based on various aspects of their identity, including but not limited to race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. It also includes disability, as discussed above. This type of bullying can take many forms, including physical violence, verbal abuse, social exclusion, and cyberbullying.

We briefly discuss a few of the identity markers that are common targets of identity-based bullying:

- Race and Ethnicity:

The study carried out by Galán et al. (2021) involving 3,939 participants reported a mean age of 15.7 years (SD = 1.3). Among these learners, 36.3% identified as Black/African American, 53.7% as assigned female at birth, 32.6% as belonging to a sexual minority group, and 10.0% as gender diverse. The findings indicated that race/ethnicity-based experiences of bullying were prevalent, with 9.5% (375 learners) reporting such experiences, while 5.8% (209 learners) were identified as perpetrators of bullying. Notably, youth with multiple stigmatised identities faced even higher rates of victimisation and perpetration. Gender-diverse Black and Hispanic youth reported the highest rates of experiences with identity-based bullying. The study also established a correlation between experiencing identity-based bullying based on multiple stigmatised identities and adverse outcomes, including delays in accessing well-care services. This underscores the significant impact of intersecting social identities on bullying experiences and highlights the importance of addressing these forms of victimisation within preventative and intervention strategies.

- Gender and Sexual Orientation:

LGBTQ+ students often face bullying related to their gender identity or sexual orientation. The research carried out by Atteberry-Ash et al. (2019) reveals significant concerns regarding the safety of LGBTQ+ youth in schools, noting that these students experience higher risks of feeling unsafe, being bullied, and skipping school compared to their cisgender heterosexual peers. Transgender students, irrespective of sexual orientation, face the greatest challenges, primarily due to societal homophobia and transphobia. Intersectionality is emphasised, revealing that students of colour face even greater safety challenges. The lack of inclusive anti-bullying policies and mechanisms in many school districts perpetuates these risks, stressing the need for systemic change. Their research shows that only 10% of school districts in the US have explicit anti-bullying policies that include LGBTQ+ youth.

These findings by Atteberry-Ash et al. (2019) highlight the urgent need for the educational system to implement inclusivity training for teachers and staff to adequately support LGBTQ+ youth. They are of the opinion that teachers informed about LGBTQ+ issues are more effective in intervening during bullying. Building relationships between students and supportive adults, as well as between peers can enhance feelings of safety, especially for LGBTQ+ youth. A comprehensive curriculum reflecting diverse identities is essential to foster a safe learning environment.

- Religion

The discussion will focus on two aspects of bullying as they relate to religion. The first is where individuals may be targeted for their religious beliefs or practices. The second is where individuals, especially those who are viewed to have “non-conforming” gender and sexual orientation, are harassed under the guise of religion.

- Bullied because of religious beliefs

The systematic review by Sapouna, de Amicis, and Vezzali (2023) outlines significant findings related to bullying victimisation among religious minorities. The studies reviewed indicate a strong correlation between visible expressions of religious identity (such as religious coverings) and increased risk of bullying victimisation. This was particularly relevant for Muslim and Sikh youth in the USA, Muslim and Christian youth in the UK, Jewish youth in Australia and Muslim youth in Nordic countries (Estonia, Finland, Sweden). Thus, the visibility of practising one’s religion becomes a target for bullying, highlighting the challenges faced by individuals in minority religious groups. The study also revealed that many of these bullying incidents are under-reported. This cycle of silence can perpetuate victimisation as schools remain unaware of the issues. Learners from religious minorities have perceived that school policies and practices may be biased against their beliefs. In addition, in certain cases, negative or dismissive reactions from teachers can lead students to internalise their victimisation as “normal”. Hence, the authors indicate a critical need for teacher training and awareness. In fact, research suggests that a sense of belonging and perceived support for cultural diversity can help reduce incidents of bullying based on ethnicity/race. This underscores the importance of fostering an inclusive environment in schools.

-Bullied/harassed due to gender and sexual orientation under the guise of religion

In contrast to individuals who are bullied for their religious beliefs, individuals who do not conform to the religious views of gender and sexual orientation can be bullied under the guise of religion. The study conducted by Newman, et al. (2018) aimed to investigate how religious discourse contributes to the bullying of sexual and gender minority youth (SGMY) by examining the perspectives of service providers and educators in Toronto, Canada. It focused on how religious beliefs and community dynamics operate within the broader social ecology affecting SGMY. The researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 key informants, including educators, service providers, and administrators who work with SGMY. The interviews were analysed thematically to identify patterns of religiously based bullying and potential interventions. The study found significant use of religious language to justify bullying behaviours, such as referencing scriptural condemnations of sexual and gender minority identities. This discourse often equates SGM identities with immorality, creating a hostile environment for affected youth (Homophobic Religious Discourse). Places of worship and faith-based schools perpetuated negative messages regarding SGM identities, often leading to direct harassment or exclusion of SGMY in these spaces (Religious Settings’ Influence). Victims of religiously based bullying exhibited higher levels of internalised homophobia and experienced rejection not only from peers but also from family and religious community members, leading to heightened emotional and psychological distress (Impact on SGMY). The study discusses “sexual orientation change efforts” (SOCE), where religious families and institutions pressure SGMY to change their sexual orientation, further entrenching feelings of guilt and alienation (Conversion Therapy and SOCE). The authors suggest that interventions should occur at multiple levels of the social ecology, including:

- Engaging religious institutions in discussions about acceptance and integration of SGM identities to counteract harmful narratives;

- Providing tools and strategies for educators and service providers to recognise and effectively respond to religiously based bullying; and

- Establishing safe spaces within churches and community organisations for SGMY to affirm their identities without fear of discrimination.

- Socioeconomic status

Typically, it is assumed that learners from lower-income families may experience bullying related to their economic situation. The meta-analysis undertaken by Tippett and Wolke (2014) investigates the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and bullying roles (victims, bullies, and bully-victims) in response to increasing public health concerns about the impact of bullying on children’s health and well-being. The study includes findings from 28 studies demonstrating that, while there are associations between SES and bullying, these relationships are weak. Victims of bullying are more likely to come from low SES backgrounds. Conversely, children from high SES backgrounds show a negative relationship with victimisation. The findings reveal that bullying perpetration has a weak connection to SES. Children from low SES backgrounds show a slight association with bullying others, while those from high SES show less likelihood to be bullies. Bully-victims (those who are both victims and bullies) are also more likely to come from low SES backgrounds, but no significant relationship exists with high SES. In conclusion, the analysis concludes SES plays a significant, albeit weak, role in predicting bullying behaviour and victimisation among children. Specifically, low SES is associated with increased risk of being victimised or being a bully-victim. The association between SES and bullying perpetration is minimal, suggesting that bullying behaviours are not limited to specific socioeconomic groups. The findings suggest that interventions to combat bullying should not be exclusively focused on low SES children. Instead, efforts should target all children, as bullying is pervasive across different socioeconomic backgrounds.

d. Microaggression

Because of the perceived subtlety of microaggression, it may not always be viewed as bullying, but it may be even more pervasive, hence the need for separate sections.

The term “microaggression” was first introduced by psychiatrist Dr. Chester M. Pierce in the 1970s to describe the verbal and non-verbal insults experienced by African Americans (Pierce, 1970). Since then, the concept has broadened to encompass a wide array of interactions that reflect and perpetuate societal prejudices based on various aspects of identity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and socioeconomic status.

Microaggression is characterised as “subtle, stunning, often automatic, and non-verbal exchanges which are “put-downs” of people from minority and marginalised statuses (Pierce et al., 1977). Microaggressions are examples of subtle, verbal, behavioural, or environmental offences, intentional or not, directed at individuals from marginalised groups or underrepresented groups (Sue et al., 2007). These groups include those defined by gender, race/ethnicity, sexuality, and socioeconomic status.

Microaggressions are distinctive in their subtlety; unlike overt acts of racism or sexism, they often manifest in daily interactions and may be perceived as innocent or even benign by those delivering them. However, the cumulative effect of these microaggressions can cause significant emotional distress for individuals who experience them. Research has shown that microaggressions can lead to adverse psychological outcomes, including increased levels of anxiety, depression, and stress among marginalised individuals (Sue et al., 2007; Nadal, 2011). These experiences can erode self-esteem and contribute to feelings of alienation or marginalisation in both social and professional settings.

Types of Microaggressions

To better understand microaggressions, it is helpful to categorise them into three main types: microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations. Each type differs in intention and expression, but collectively contributes to the perpetuation of systemic biases.

- Microassaults

Microassaults are explicit and intentional discriminatory acts that are often overt and aimed at inflicting emotional harm on another individual based on their identity. Unlike microinsults or microinvalidations, microassaults are consciously executed, reflecting a clear intent to demean or belittle. This type of microaggression can take many forms, including racist imagery, derogatory slurs, or outright refusal of service based on an individual’s race or ethnicity (Sue et al., 2007).

Microassaults include concrete actions such as displaying racist symbols (e.g., a swastika) in public, using racial slurs toward individuals of color, purposefully avoiding someone based on their identity, mocking accents or language disabilities, and making any theme discriminatory jokes. For instance, a white person using a racial slur to refer to a black individual or a business owner refusing service to a Muslim person due to their attire are clear manifestations of microassaults (Sue et al., 2007; McAndrews et al. 2017).

Unlike microinvalidations and microinsults (discussed below), microassaults are often conscious acts. According to researchers, racial microassaults are small-scale attacks directed at persons of marginalised or minority groups. While some microaggressions (e.g. micro-assaults) can fit the common definition of bullying, microaggressions can also be unintentional, do not always involve repeated interactions between specific individuals, and the power imbalance often reflects broader structures of oppression rather than individual power based on size, strength, or popularity (Walton & Niblett, 2013). As seen, although microassaults are categorised as “micro,” they are not so “micro” in terms of intentionality and obviousness (McAndrews et al. 2017).

- Microinsults

Microinsults involve comments or actions that unintentionally convey rudeness or insensitivity toward an individual’s identity. These statements often stem from ingrained stereotypes and can undermine a person’s self-worth by implying that they are lesser in some way. Microinsults may occur in the form of seemingly complimentary remarks that carry an underlying message of inferiority. Microinsults are generally unconscious behavioural or verbal slights that demean one’s heritage, racial identity, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, etc. (Sue et al., 2007, Minikel-Lacocque, 2013).

For example, telling an African woman, “You’re so articulate for someone from your background,” may be intended as a compliment but reinforces stereotypes about linguistic abilities based on ethnicity (Nadal, 2011). In the classroom, the following are regarded as microinsults (Kickboard, 2018):

- A learner’s academic potential is judged based on their racial background.

- A parent’s commitment to their child’s education is presumed based on their appearance, manner of speaking, or place of residence.

- Learners of colour are often denied the same opportunities as their white counterparts.

- A black or brown learner is often unfairly perceived as threatening or aggressive.

Such microinsults can accumulate over time, leading to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt among those targeted, particularly in professional environments.

- Microinvalidations

Microinvalidations occur when comments or behaviours negate or dismiss the experiences, thoughts, or feelings of marginalised individuals. These statements often convey disbelief in the individual’s lived experiences, significantly contributing to feelings of alienation and frustration. Microinvalidations are particularly damaging because they can make the individual feel invisible or unworthy of recognition.

An example of microinvalidation would be a white individual telling a black person, “I don’t see colour. We are all just people,” which dismisses the unique challenges and experiences rooted in racial identities and minimises the impact of systemic racism (Sue et al., 2007). This type of microaggression can be especially prevalent in discussions about race and identity, where the lived realities of marginalised groups may be glossed over or overlooked entirely.

Microinvalidations are often unconscious verbal or behavioural actions that exclude or neutralise thoughts, emotions, or knowledge of people of marginalised or minority groups (Sue et al., 2007; Minikel-Lacocque, 2013). For example, if you accuse someone of overreacting when they are simply responding to someone making racist statements, that dismisses the seriousness of the situation.

Microaggressions represent a significant yet often overlooked form of discrimination that can adversely affect the mental health and well-being of individuals from marginalised backgrounds. By understanding and addressing the different types of microaggressions — microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations — society can foster more inclusive and equitable environments. Recognising and addressing microaggressions, therefore, is crucial for dismantling systemic oppression and creating spaces where all individuals feel valued and acknowledged.

Recognising microaggressions and the messages they send

Before you can respond to a microaggression, it is necessary to recognise that one has occurred. The following examples are adapted from the University of California, Office of the President published in 2015 (Center for Educational Effectiveness [CEE], 2018).

Table 1: Recognising microaggressions and the messages they send

| Microaggressions | Examples | Messages |

|---|---|---|

| Ascribing intelligence. Evaluates someone’s intelligence or aptitudes based on their race and gender. | (To a woman of colour): “I would never have guessed you were a scientist!” Or “How did you get so good at maths?” | People of colour and/or women are not as intelligent and adept at maths and science as white people, and men. |

| Assumption of criminality/danger. Presumes a person of colour to be dangerous, deviant or criminal because of their race. | A white person crosses the street to avoid a person of colour, or a professor asks a young person of colour in an academic building if they are lost, insinuating they may be trying to break in. | People of colour don’t belong here, they are dangerous. |

| “Othering” cultural values and communication styles. Indicates that dominant values and communication styles are “normal” or ideal. | Structuring grading practices in such a way that only verbal participation is rewarded, failing to recognise cultural differences in communication styles, and varying levels of comfort with English verbal communication. | Conform and/or assimilate to the dominant culture. |

| Second-class citizens. Awards differential treatment. | Calling on male learners more frequently than female learners; mistaking a learner of colour for a service worker. | Men’s ideas are more important; people of colour are destined to be servants. |

| Gender/sexuality exclusive language. Excludes women and the LGBTQ+ community. | Forms that only offer male/female choice for gender; use of the pronoun “he” to refer to all people. | There are only two acceptable genders; men are normative and women are derivative. |

Adapted from the University of California, Office of the President published in 2015 (Center for Educational Effectiveness [CEE], 2018).

What is the prevalence of bullying across different settings and contexts?

Bullying remains a pressing issue with significant global implications. Understanding its prevalence is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. Current research provides a comprehensive overview of bullying rates, highlighting significant trends and variations.

- Global prevalence and trends of bullying

According to the 2019 UNESCO Report, a significant issue regarding school violence and bullying indicates that nearly one-third of school-aged children and adolescents experience bullying (UNESCO, 2019). In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 20% of youth experienced bullying in school, with 14% of adolescents facing bullying weekly. Additionally, 33% of middle school students experienced cyberbullying at least once a week. Research indicates that bullying affects a substantial portion of adolescents worldwide. According to data from over 279,000 youth in 44 countries and regions, the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) report (Cosma, Molcho Pickett, 2024) provides the following key insights:

- Bullying other students: On average, 6% of adolescents report bullying other students at school. Boys are more likely (8%) than girls (5%) to engage in this behaviour.

- Experiencing bullying at school: Approximately 11% of adolescents report being bullied at school, with no significant gender differences.

- Cyberbullying others: About 12% of adolescents, or 1 in 8, report cyberbullying others. Boys (14%) are more likely than girls (9%) to engage in cyberbullying, reflecting an increase from 2018 (boys up from 11% and girls from 7%).

- Experiencing cyberbullying: Around 15% of adolescents report having been victims of cyberbullying, with rates similar between boys (15%) and girls (16%). This represents an increase from 2018, with boys rising from 12% to 15% and girls from 13% to 16%.

- Physical fighting: About 10% of adolescents have been involved in physical altercations, with a clear gender disparity: 14% of boys versus 6% of girls.

- Variability in prevalence rates

Survey prevalence rates of bullying can vary significantly due to several factors, including the definitions used, the frequency of bullying considered, and the time periods investigated. Smith (2016) notes that variations in definitions—such as whether they include cyberbullying or different forms of bullying—and differences in how frequently bullying is reported (e.g. once a month versus once a year) can affect prevalence rates. Additionally, the timing of questionnaire administration (e.g. at the start or end of the academic year) can impact reported rates, making cross-study comparisons challenging.

- Prevalence regarding types of bullying

The prevalence of different types of bullying also shows significant variation. The results of the Global School-based Student Health Survey between 2003 and 2015 in 65 countries revealed that the most common type of bullying was verbal (66.36%), followed by physical (24.02%), and the least common type was neglect (9.62%). Geographically, verbal bullying was highest in the Americas (71.09%) and lowest in Africa (61.75%); neglect was highest in South East Asia (11.10%) and lowest in the Eastern Mediterranean (7.11%); physical bullying was highest in Africa (28.98%) and lowest in the Americas (18.84%) (Man, Liu, & Xue, 2022, p.7). Smith et al. (2016) aslo reported that cyberbullying is an emerging concern, with 15% to 20% of adolescents reporting involvement.

Understanding the prevalence of bullying, along with the factors influencing these rates, is essential for designing effective prevention and intervention strategies. Efforts must continue to address the varying types of bullying and adapt approaches based on regional and temporal differences to effectively reduce the impact of bullying on adolescents.

Let us pause and reflect

What are the “roles” of those involved in a situation where bullying occurs?

As earlier discussion demonstrates, the concept of bullying is difficult to define. Similarly, ascribing names or terms to the role players in the situation where bullying occurs is not simple either. The choice of language is crucial, as it can profoundly influence the dynamics of the bullying process, just as it does in many psychological contexts. It is essential to avoid language that either glorifies or excessively vilifies the individual engaging in bullying, as well as terms that diminish the agency of the person experiencing bullying, rendering them a passive victim. This section explores the diverse experiences of those involved in bullying, acknowledging that the terminology used is not exhaustive.

Numerous studies on bullying have typically categorised children into three groups: aggressors, aggrieved, and aggressor-aggrieved. Additionally, other roles include bystanders, defenders, assisters, and reinforcers.

Aggressor (bully, perpetrator, who starts bullying)

Perpetrators or bullies intentionally harm or cause suffering in others without facing retaliation (Menabo et al., 2024). While these individuals are generally viewed as disliked and aggressive, a significant portion is also perceived as popular, powerful, possessing leadership qualities, and having various competencies and advantages. The reason for this difference in perception is social power. Bullies who are socially more powerful are perceived more positively by their peers (Vaillancourt et al., 2003). Rettew and Pawlowski (2022) referred to these groups, which differ in terms of social power, as ‘alpha bullies’ and ‘delta bullies.’ Alpha bullies are described as a socially powerful group with fewer pathologies, whereas delta bullies are characterised by weaker social skills and a higher likelihood of cognitive and behavioural issues. Considering this distinction when assessing bullying behaviour is crucial to developing accurate and effective intervention strategies. However, a typical bully generally struggles with resolving conflicts and faces academic difficulties. Such individuals often hold negative attitudes and beliefs about others, come from families marked by conflict and poor parenting, view school unfavourably, and are negatively influenced by their peers (Cook et al., 2010). In addition to the bully’s social power, the level of hostility is also a notably variable in the bullying process. The bully’s hostility increases the emotional harm inflicted on the victim (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2018).

The Aggrieved (victim, target, bullied)

Victims are those who suffer attacks repeatedly over an extended period. They are typically characterised as being defenceless (Menabo et al, 2024). Anyone can become a target of bullying, even when they have not done anything to provoke it or make a mistake. Often, it only takes being in the wrong place at the wrong time (Sticks and Stones, n.d.). The ones who lack social skills, think negative thoughts, experience difficulties in solving social problems, and come from disadvantaged families, schools, and community environments are risky groups for bully victimisation (Cook et al., 2010). Bullies are often driven by the vulnerable and distressed reactions of their intended victims, which gives them a sense of power and control. Children who are hyper-sensitive, cautious, anxious, passive, or submissive —and lack determination, assertiveness, or decisiveness— are more likely to be singled out than other children. Those who respond to bullying with vulnerability and distress are often subjected to repetitive aggression. What differentiates children who are not victimised from those who are is not their physical strength, but rather their capacity to either stand up to or distance themselves from the bully’s aggressive behaviour (Sticks and Stones, n.d.). Victims may not always recognise that they are being bullied, and even if they do, they might not seek help. Therefore, it is essential to observe and identify signs of bullying. Here are some warning signs to detect bullying victimisation (UNICEF, n.d.):

-

-

- Unexplained physical marks, such as bruises, scratches, broken bones, or healing wounds,

- Fear of going to school or participating in school events,

- Signs of anxiety, nervousness, or heightened vigilance,

- Having few or no friends at school or outside of school,

- Suddenly losing friends or avoiding social situations,

- Personal belongings such as money, clothing, or electronics being lost or destroyed,

- Declining academic performance,

- Frequent absenteeism or calling from school asking to go home,

- Trying to stay close to adults at all times,

- Difficulty sleeping, including experiencing nightmares,

- Complaining of headaches, stomach aches, or other physical ailments,

- Regularly appearing distressed after spending time online or on their phone without a clear reason,

- Becoming unusually secretive, especially regarding online activities,

- Displaying aggression or having frequent angry outbursts.

-

However, observation alone is insufficient; prevention plans should also include raising awareness of threatening cues because research shows that bullies-victims are more aware of threatening cues like eye movements; in contrast, victims tend to avoid them by gaze (Menabo et al.2024).

The Aggressor-aggrieved (bully-victims)

A distinct group from the bully and the victim is the bully-victim who both perpetrates bullying and is a victim of bullying. While the exact cause of bullying-victimisation in certain learners remains unclear, prior research has indicated that characteristics such as diminished empathy, restricted prosocial conduct, weak familial ties, or issues with controlling their anger could contribute to their profile (Menabo et al, 2024). The typical bullies-victims (someone who bullies and is bullied) have negative attitudes and beliefs about himself or herself and others. They have trouble with social interaction, do not have effective social problem-solving skills, have low academic achievement, and are not only rejected and isolated by peers but also negatively influenced by the peers with whom they interact (Cook et al., 2010). In comparison to the other groups, bully-victims are the most despised and are more prone to self-harm and experience higher levels of depression (Menabo et al, 2024). Bullies-victims constitute the most aggressive group among those involved in bullying roles (Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002). Due to their aggression, they receive less support from teachers and peers compared to pure bullies and pure victims (Shao et al., 2014).

The Bystander (uninvolved)

School bullying is a collective issue involving not only the bullies and victims but also a significant number of witnesses who observe the bullying behaviour. There are four distinct bystander roles: assistant, reinforcer, outsider, defender (Salmivalli et al., 1996). Bystanders aren’t passive actors; in contrast, they are critical actors in deterring the demoralising and damaging impacts of bullying (Padgett and Notar, 2013). Also, even if they witness it once, bystanders (especially those who have previously been in the victim role) may experience depression, anxiety, substance use, and somatic symptoms related to bullying. (Rivers et al., 2009; Mishna & Van Wert et al., 2014).

Supporter of Aggressor (pro-bully/ assistant, reinforcer)

The assistant and reinforcer roles are described as being pro-bullying. The main and typical behaviour of these roles is supporting the aggressor. The role of the supporter of the aggressor or the pro-bully is composed of individuals who actively support the bully through either aggressive behaviour or laughter and jeering that encourages the bully (Menabo et al, 2024). Assistants do not initiate bullying; they join it after someone else does (Salmivalli, 2010). Reinforcers are present in the bullying case, as are other bystanders. However, they may display varied behaviours, which can be active or passive. They may be witnesses (not responding or acting regarding bullying) or support the bully. They also may be more active bystanders. Furthermore, they could laugh or actively encourage the bully, reinforcing the bully’s aggressive behaviours. The nuance between assistant and reinforcer roles is that reinforcers do not actively join the bullying (Monks & O’Toole, 2020).

Supporter of aggrieved (defender)

In sharp contrast, the defender (as a supporter of the aggrieved) actively stands up for the victim by encouraging them to tell an adult, protecting, supporting and (Menabo et al, 2024; Reinjtjes et al., 2016). Beyond these, defenders may also intervene in bullying, which could directly stop it (Reinjtjes et al., 2016). Defenders’ interventions can stop 60% of ongoing bullying within 10 seconds, and the victims whom defenders support have less psychological maladjustments and negative outcomes (Hawkins et al., 2001; Ma & Chen, 2019). Thus, it is clear that adding defenders to prevention and intervention plans is critical for effectively addressing bullying. While Pozzoli and Gini (2010) state that defending a victim can be risky because the defender may confront a powerful bully and their supporter, recent research suggests that defending was not significantly associated with future victimisation, suggesting that it is not generally a risk factor for victimisation (Malamut et al., 2023). As seen, defenders play an influential role in preventing bullying. Therefore, equipping them with the necessary skills and supporting them in potentially risky situations (even if the likelihood is low) is crucial for preventing bullying.

Theories related to bullying

Examining theoretical frameworks that shed light on the fundamental causes and contributing elements of bullying is necessary to comprehend and address it. Some of these theories are briefly summarised below.

- Social learning theory

According to Albert Bandura (1973, 1983), bullying behaviour is learned through imitation and observation. According to this theory, people who see that aggressive behaviours are rewarded or ignored are more inclined to bully others. This idea highlights how violent behaviour is shaped by role models such as parents, friends, and celebrities (athletes, singers, actors, social media influencers, etc.). According to Bandura’s research, children who saw aggressive behaviours were more inclined to imitate these behaviours. To better understand Social Learning Theory, you can watch the video of Bandura’s Bobo Doll experiment.

- Frustration and aggression theory

Frustration and aggression theory, first proposed by Dollard et al. (1939) and later developed by Berkowitz (1989, 1993), suggests that bullying and other forms of aggression are caused by frustration. It implies that people may react angrily out of dissatisfaction when they don’t succeed in achieving their aims. This theory defines bullying as a way of expressing anger or regaining power and explains reactive aggression as a reaction to perceived dangers or obstacles.

- Social dominance theory

According to the social dominance theory, bullying is a tactic used to create and uphold social hierarchies. Aggression is a tactic used by people to establish dominance and a better standing in social organisations. This idea contributes to the explanation of why bullying frequently entails an imbalance of power, with bullies wanting to maintain their social standing and influence over their victims. It draws attention to how social structures support and encourage bullying behaviour (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Furthermore, there is a personality trait known as social dominance orientation (SDO) represents a person’s “degree of preference for inequality among social groups” (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, Citation1994, p. 741).

- Ecological systems theory

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding bullying by accounting for multiple levels of influence. This concept examines the ways in which a person’s behavior is influenced by a variety of contexts, such as their family, peers, school, community, culture, and media. The importance of the broader social environment in shaping bullying behaviors and responses is emphasised (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Espelage & Swearer, 2003).

- Developmental psychopathology

This approach focuses on the interactions between environmental factors, developmental pathways, and risk factors that shape bullying behavior. The analysis considers the ways in which early experiences, personality traits, and contextual factors interact to shape bullying throughout time. Volk et al. (2012) claim that developmental psychopathology sheds light on the ways in which individual and environmental factors interact to shape bullying behavior and its outcomes.

- Attachment theory

According to John Bowlby’s attachment theory (1969), early relationships with caregivers have an impact on bullying and other subsequent social behaviors. Strong attachment relationships are the foundation of constructive social interactions, yet insecure attachments can feed aggressive or bullying behavior. This idea emphasizes how early relational experiences shape emotional and behavioral reactions (Bowlby, 1969; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

- Self-control theory

The self-control theory of Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) states that a lack of self-control is a major contributing factor to violent behavior, which includes bullying. Individuals who struggle with emotional regulation and behavioral self-control are more likely to act impulsively and violently. The theory states that self-control exercises are essential for putting an end to bullying and other antisocial behavior.

These theories, along with relevant research, provide a thorough knowledge of the intricate dynamics and underlying aspects of bullying. They offer insightful information that can be used to create interventions and preventative measures that effectively address and stop bullying behavior.

Motivating, risk, and protective factors of bullying

Motivating factors

Understanding the differences between instrumental and reactive aggression is crucial to comprehending the motivating factors. Responding to a threat with harm is the goal of reactive aggression, which is motivated by resentment and frustration (Berkowitz, 1989, 1993; Dollard et al., 1939). By contrast, instrumental aggression is associated with joy and excitement and is a planned activity to attain certain aims (Bandura, 1973, 1983). Gradinger, Strohmeier, and Spiel (2009) found that combined bully-victims (traditional and cyber) bullies displayed the highest levels of both reactive and instrumental aggression compared to traditional bullies, cyberbullies, and non-bullies. A subsequent study (Gradinger, Strohmeier, & Spiel, 2012) showed that cyberbullies are primarily driven by power and enjoyment, traditional bullies by anger, and combination bullies by a mix of anger, power, affiliation, and fun.

According to Roland and Idsoe (2001), aggressors have two main goals: power and affiliation. Students often resort to violence to gain control or form favourable relationships. Bullying motivations also vary by age. For instance, among eighth graders, bullying is associated with power and affiliation but not anger, whereas fifth graders show connections with power, affiliation, and anger. Gender differences reveal that girls’ bullying is more linked to affiliation and boys’ to power.

Fluck (2017) investigated the causes of bullying and found that one of the five causes (power, revenge, sadism, ideology, and instrumental) was not confirmed (instrumental), but the other four were confirmed. In addition, the qualitative data of the study revealed new reasons (peer pressure and self-control). The seven reasons mentioned in Fluck’s research are:

Power: Many bullies are driven by a desire for power and dominance over others. This can manifest in various ways, such as controlling or intimidating peers to assert their superiority.

Revenge: Some individuals resort to bullying as a form of retaliation for perceived wrongs or injustices they have experienced. This response is often driven by a deep sense of hurt, betrayal, or frustration, leading them to target those they believe have wronged them in some way.

Sadism: In some cases, bullies may derive pleasure from inflicting pain or suffering on others. This sadistic motivation is linked to a lack of empathy and a tendency to dehumanise victims.

Ideology: Bullying can be motivated by ideological beliefs, such as racism, xenophobia, sexism, or homophobia. Bullies may target individuals who they perceive as different or inferior based on these beliefs.

Instrumental: Bullying can be used as a means to achieve certain goals, such as gaining social status, securing resources, or influencing group dynamics.

Peer Pressure: The desire to fit in with a certain peer group can motivate individuals to engage in bullying behaviour, especially if the group values or rewards such actions.

Lack of Self-Control: Some bullies may have poor impulse control and act out aggressively without considering the consequences of their actions.

Bullies often cite retaliation as a key motivation, while victims report power and sadism. Understanding these motivations is crucial for developing effective interventions to address and prevent bullying behaviour.

What is the relation between empathy and aggression?

Zych, Ttofi, and Farrington (2017) found that bullies generally lack empathy and exhibit callous-unemotional traits, correlating with repeated bullying. Bullied individuals showed low empathy, while defenders exhibited higher empathy levels.

- Lack of empathy in bullies: Bullies typically have low levels of both cognitive and affective empathy. This means they struggle to understand others’ perspectives and do not feel concern for their victims’ distress. This lack of empathy allows bullies to inflict harm without feeling guilt or remorse.

- Callous-unemotional traits: Bullies often display traits such as a lack of guilt, shallow emotions, and insensitivity to others’ feelings. These traits are associated with persistent and severe bullying behaviour.

- Empathy in victims: Victims of bullying often have lower empathy scores compared to non-victims. This could be due to the emotional toll of being bullied, which can impair their ability to relate to others emotionally.

- Empathy in defenders: Individuals who stand up against bullying, known as defenders, generally possess higher levels of empathy. Their ability to understand and share the feelings of others drives them to intervene and support victims.

To sum up: The relationship between empathy and aggression highlights the importance of fostering empathetic skills in children to prevent bullying and promote prosocial behaviour.

Risk factors

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of an individual engaging in or becoming a victim of bullying and aggression. Here are some of the risk factors:

Individual factors: Traits such as low self-esteem, self-efficacy, aggression, and lack of empathy can make one more likely to bully or be bullied (i.e. Bandura et al., 2003; Donnellan et al., 2005; Jollife & Farrington, 2006; Salmivalli, 2001).

Family factors: A lack of parental supervision, harsh or inconsistent discipline, and exposure to family conflict can contribute to bullying behaviour (i.e. Bowes et al., 2009; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Stavrinides et al., 2015).

School factors: Schools with weak anti-bullying policies and mechanisms, lack of supervision, location of school, and a negative school climate are environments where bullying is more likely to occur (i.e. Bowes et al., 2009; Payne & Gottfredson, 2004).

Peer factors: Peer pressure, association with delinquent peers, and social isolation can increase the risk of bullying (i.e. Bowes et al., 2009; Salmivalli, 2010).

Neighbourhood factors: Neighborhood safety, neighborhood structural disadvantage, and residental instability can increase the risk of bullying (i.e. Choi et al., 2021; Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2012)

Protective factors

Protective factors can help mitigate the risk of bullying and bullying victimization and their effects. Here are some of the protective factors:

Strong social support: Positive relationships with family, peers, friends, and teachers can provide emotional support and reduce the likelihood of bullying (i.e. Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Mishna et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2009).

Effective school policies: Schools that implement comprehensive and regular anti-bullying programs and mechanisms and foster a positive school climate can reduce bullying incidents (i.e. Hall, 2017).

Emotional and social skills: Fostering empathy and assertiveness in and with children, and teaching conflict resolution strategies can protect against bullying behaviour and victimisation (i.e. Ttofi et al., 2014).

Parental involvement: Active parental engagement in a child’s life, including monitoring activities and promoting open communication, can serve as a buffer against bullying (i.e. Simmons-Morton et al., 2004; Wienke et al., 2009).

Whom to who?

Schools in many ways are just like all other types of organisations. As long as there are humans in an organisation, its operation will rely on relationships. The dynamics of these relationships can lead to individuals or groups feeling bullied at times.

When we think of school violence or bullying, we tend to think of it as something which happens between individual learners or individuals and groups. Whilst learners are the main group, they are not the only members of the school community who can experience bullying. Adult bullying occurs in schools as it does in other workplaces: teachers can feel bullied by leadership and vice versa (Fahie, 2014), parents can feel mum/dad-shamed by other parents at the school gate, and it is not uncommon for individuals or groups of parents to make a teacher feel bullied. In fact, it is notable that since the Covid pandemic this particular type of bullying is more spoken of within the teaching community. The lack of face-to-face contact between parents and teachers during the pandemic led to all communication happening online. Parents just like everyone else can feel a little braver in online communication: for example, it is a lot easier and quicker to press send on an abusive email than it is to arrange a meeting with a teacher and to say those same things directly to them.

This is not to say that teachers do not engage in this type of behaviour themselves. Depending on the culture of the school you work in, you may find yourself feeling bullied by a colleague, being ostracised in the staffroom or feeling harassed by school leadership.

Learners can often feel as though the teacher does not like them or is picking on them. They may feel as though they are always in trouble and can do nothing right. As teachers, we are human and just like our learners we will not like everyone we interact with on a daily basis. This may include some of the learners we work with. We have a professional responsibility to ensure that learners never pick up on this. We must ensure that learners feel valued and heard in our classrooms. Unfortunately, it does happen that some teachers cannot maintain their professionalism and bully particular learners. If you notice this in yourself or a colleague, you have a moral and professional obligation to raise it with school leadership.

An increasing trend in secondary and higher education is learner/teacher bullying, which is not as common in primary level education. Such bullying can include cyberbullying as well as traditional bullying. Learner/teacher bullying is most commonly trolling, creation of false profiles/accounts and posting of fake images. A recent study conducted by the Association of Secondary Teachers in Ireland found that 18% of respondents to their survey had experienced some form of cyberbullying from students or parents (RedC ASTI 2024 ).

Bullying behaviour has negative effects on all those at whom it is aimed. No group within a school community experiences bullying behaviour and remains unscathed. Learners however lack the life experience, resilience and understanding of bullying that adults have and are therefore more greatly affected.

What are the effects of bullying?

Bullying remains a significant issue that impacts both individuals and societies. Studies conducted in the twenty-first century have shown that bullying has a variety of negative consequences on the physical, psychosocial, and academic domains.

Physical consequences

Bullying can have immediate negative effects on one’s physical health, like physical harm, or it can have long-term consequences, like headaches, disturbed sleep, or somatisation. But it can be challenging to pinpoint the physical after-effects of bullying in the long run and connect them to previous bullying conduct as opposed to other factors like anxiety or other traumatic childhood experiences, which can also have long-term physical effects that persist into adulthood (i.e. Hager and Leadbeater, 2016).

Psychosocial consequences

The psychosocial ramifications of bullying are extensive and multifaceted. People who are bullied may experience internalising and externalising problems. Anxiety, dread, depression, self harming, and social disengagement are examples of internalizing symptoms (i.e., Juvonen and Graham, 2014; Vaillancourt et al., 2013). Anger, violence, conduct issues, including a propensity for dangerous and impulsive behavior as well as criminal activity, are examples of externalising behavior (i.e., Patchin et al., 2006). Substance use and abuse are examples of externalising difficulties. Bullying has been linked to long-term psychological suffering, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic anxiety (i.e. Nielsen et al., 2015). Bullying has an impact on social interactions and behaviour as well. Friendship formation and maintenance can be difficult for victims, which can worsen feelings of loneliness and isolation. According to research by Hawley and Williford (2015), social dominance is important in the dynamics of bullying since it causes problems for both bullies and victims in their interactions with peers.

“Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words can never hurt me.”Do you think that’s the case in reality?

Academic consequences

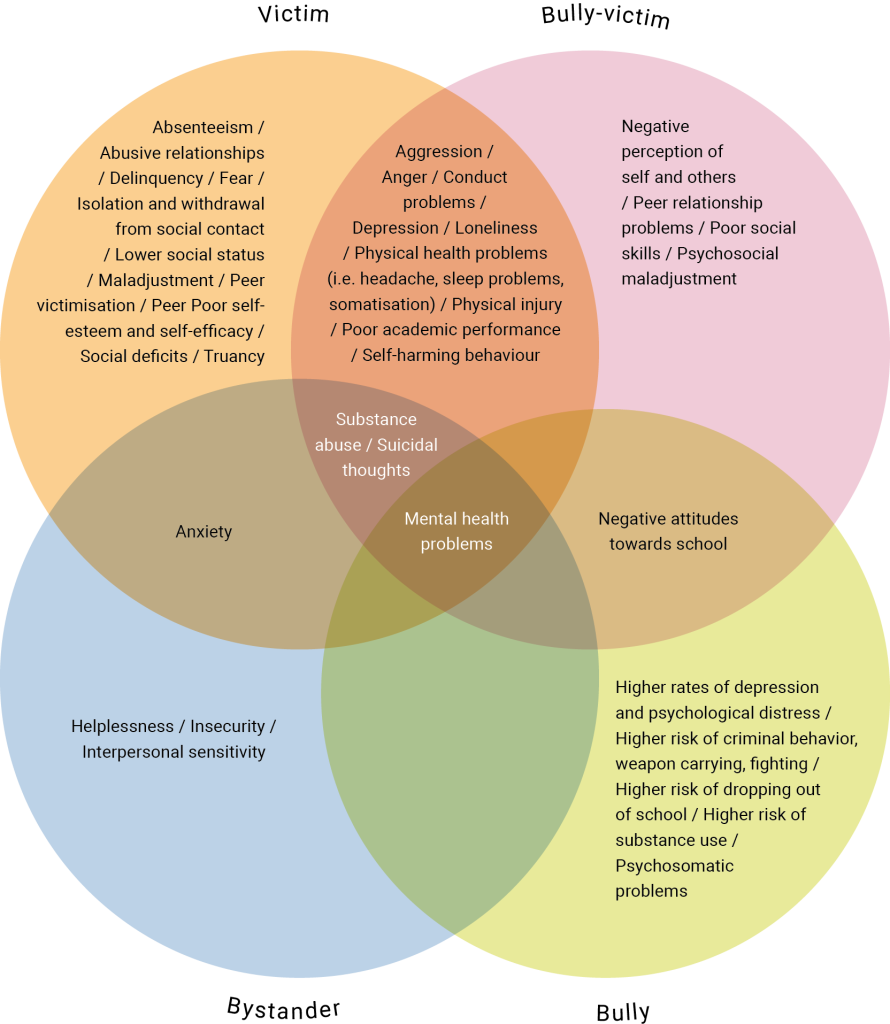

Bullying has an effect on kids’ academic performance and participation as well as beyond the classroom. Bullying victims experience lower academic accomplishment, as evidenced by an increasing body of research, regardless of how grades or test scores are calculated. Children who experience bullying are more likely to experience poor academic attainment (Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010) and higher absenteeism (Juvonen et al., 2000), according to cross-sectional study. According to multiple short-term (one academic year) longitudinal studies, academic problems do not predict being the target of bullying, but rather being the victim of bullying predicts academic problems (Schwartz et al., 2005). Speaking about the negative consequences of bullying that are limited to the victim would be inadequate. This is because bullying has negative consequences on the victims as well as the bullies, the bully-victims, and the bystanders. The figure below shows the negative consequences of bullying on all students in different bullying roles as reported in different studies (Rivara et al., 2016; Vanderbilt & Augustyne, 2010).

Figure 1: Negative effects of bullying for different bullying roles

The effects of bullying on people in different roles are presented in detail in the table above. We see that some of the same negative effects are experiened by different bullying “roles” (See the colour-code across the columns). For example, physical health problems, substance use/abuse, and suicidal thoughts are experienced by three of the four groups.

Another victim group related to bullying is poly-victims. Poly-victims are one subgroup of school-age children who might be more vulnerable to the negative immediate and long-term effects of bullying victimisation. According to Finkelhor et al. (2007), poly-victims are those who exhibit high levels of traumatic symptomatology and are exposed to the following: (1) violent and property crimes (such as theft, burglary, assault, and sexual assault); (2) child welfare violations (such as child abuse and family abduction); (3) the violence of warfare and civil disturbances; and (4) being the targets of bullying behavior.

Compared to youth who did not meet the criteria for poly-victimisation, youth who were poly-victims were more likely to meet criteria for psychiatric disorders, such as being up to five times more likely to use drugs or alcohol, two times more likely to report depressive symptoms, three times more likely to report post-traumatic stress disorder, and up to eight times more likely to have comorbid disorders (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Ford et al., 2010).

Understanding the comprehensive effects of bullying is crucial for developing effective interventions. Addressing bullying requires a multifaceted approach that includes improving mental health support for victims, fostering positive social relationships, and enhancing academic support systems. It also involves creating a school environment that actively prevents bullying and supports affected individuals.

By recognising the broad impacts of bullying on psychological well-being, social interactions, and academic performance, educators, parents, and policymakers can work together to implement strategies that reduce bullying and mitigate its adverse effects.

Mechanisms of change: How can we address and prevent bullying in our schools?

In this section, we discuss the need for collaboration and a common understanding in addressing and preventing bullying in our schools. This common understanding is found in policies that guide schools on the procedures to be followed in addressing and preventing bullying at school. In turn, schools need to ensure that all teachers and learners are fully aware of their role in addressing and preventing bullying at an individual level.

Mechanisms of change – Policy level

As discussed above, bullying will not end if it remains a situation that should be solved between the bully and the bullied only. Thus, the chapter discussed the need for classroom and school strategies. However, we know that what happens at school frequently spills out into the extended environment of the learner. Hence, there is a need to broaden the scope of the area that covers bullying and its impact. In fact, several articles describe bullying as a public health concern (Gong, et al., 2024). As a result, this section will examine the national policies that discuss bullying and the strategies needed to address and prevent it.