Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Language Learning for All

Silver Cappello; Julia Schlam Salman; and Merja Kauppinen

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Tracy is a language teacher who works with newly arrived immigrants in Sweden. Here she describes some of the strategies and techniques she uses to ensure that her classroom is inclusive for all.

“I’ve been teaching in Sweden for the past 12 years and I work with newly arrived immigrant students who come to Sweden from a variety of backgrounds. They come and they are put together in a preparation class for a maximum of two years. So we have a group with different ages, abilities, ethnicities and backgrounds, all together in one class. It’s quite a challenge. In general, we are seeing a rise in multilingual classrooms. So it’s something that teachers everywhere really need to be aware of— how we recognize the diversity of our students, what they’re bringing to the classroom in terms of background and cultural experiences, and how this experience of being together with many different people is enriching and that we should celebrate it. It’s also important to think about how this experience might affect their learning identity and mark them for the rest of their school career. Therefore, we have to be positive and encouraging about their own home languages. In Sweden, we support them by using techniques such as translanguaging. We use that as a method for recognizing where they’re from, but also for integrating them into a new system.”

Tracy Fletcher-Tjernberg, High School Teacher and Researcher, Sweden

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- How do you know that your students understand you? What signs do you look for in the classroom?

- How do you get to know the linguistic and cultural background of your students?

- How do you promote and support the languages of all your students in multilingual classrooms?

Introduction to Topic

Schools today are increasingly multilingual with learners bringing different home languages and ethnolinguistic identities to the classroom. The language of instruction may be the learners’ first language (L1), their second language (L2), an additional language or a foreign language (for example, in contexts where English is a foreign language and is being used as the language of instruction) (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022). In order for the learning space to be fully inclusive, care must be taken to make the language of instruction accessible to all learners.

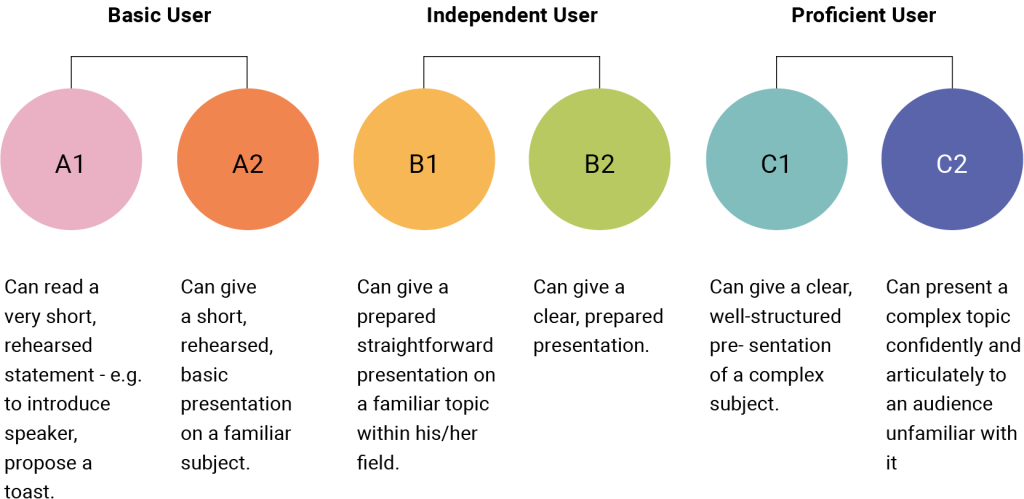

Many factors are at play when we take into consideration how learners understand the language being used in the classroom. A helpful initial starting point is a framework developed by the Council of Europe entitled the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). This provides a framework around which curricular and educational initiatives can be developed which prompt and support multilingualism and multiculturalism. The CEFR was designed to “protect linguistic and cultural diversity, promote plurilingual and intercultural education, reinforce the right to quality education for all, and enhance intercultural dialogue, social inclusion and democracy” (Council of Europe, 2022). The CEFR outlines clear standards and performance indicators for each level of language learning and includes descriptor scales which run from A1 to C2. The first level, A1, is a beginning language learner and user and C2 is someone who can use a language in all facets of their life – personal, public, professional/occupational and educational. These spheres are significant because they emphasise authentic, real-life ways in which learners use language to function and communicate.

Figure 1: CEFR Scale and short descriptors of spoken production

Another important component of the CEFR framework is the distinction between receptive language skills—what a language user can hear and understand or read and understand and productive language skills—what a user can say or write. When we focus on checking for understanding and making sure the language of instruction is accessible to all learners, this is an important distinction to bear in mind. As with language learning in early childhood, learners may be in different stages in their language acquisition. They may be able to access content and understand the subject matter in the classroom but they may not yet feel comfortable “producing” responses—for example participating in a classroom discussion (Lightbown & Spada, 2021).

It is also critical to provide learners with different modes and modalities for showing their knowledge and understanding. Termed multimodality, this practice emphasises the integration of not only written texts but also images, aural resources, video resources, movement and technology (Choi & Yi, 2016). Some learners might prefer a more “traditional” approach such as reading a text and answering questions while other learners might prefer listening to a reading text and then making a video about what they have heard. Both approaches enable learners to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding.(Sousa, 2017; Tomlinson, 2017).

Additional dimensions of the CEFR expand on receptive and productive language skills and include interaction and mediation. Both of these dimensions highlight the social component of language learning. Language usage is a social act that enables participation and interaction within a society. Particularly in multilingual classrooms, learners need to be given time to practise interacting and mediating meanings in the target language. This is especially critical for students who do not share the language of instruction and the often implicit, sociopragmatic expectations. As previously discussed, these opportunities for practice provide scaffolding for subsequent, real-life, day-to-day situations when learners will need to use the language to communicate.

A final aspect of the CEFR that is important to highlight is its framing as a “competence-based approach” to language learning (Council of Europe, 2020). In the CEFR, language learning primarily focuses on activities and interactions that are related to real world tasks. Language learners are assessed on what they can do with the language around specific communicative tasks (and not what they cannot do or do not yet know). This additive approach ensures a focus on real-life communicative competences learners are developing. It is a motivating approach that highlights the ongoing nature of language acquisition. There is always more about language to be learned but everybody, including, for example, non-verbal communication, knows and can do something with language.

With the CEFR framing our thinking, in this chapter, teachers will be introduced to three dimensions for making language more accessible to learners: mindsets, models and methods. The first, mindsets, are the epistemological frameworks—in other words the belief systems— teachers bring to the classroom which inform their teaching and learning. The second, models, are the structures teachers use to think about and organise their classrooms. Finally, methods are the actual tools and techniques teachers use in the classroom to make language more accessible to learners.

Due in part to migration, globalisation, technologization and mobility (The Douglas Fir Group, 2016) classrooms are increasingly diverse and plurilingual. Teachers may have four, five, six or more different home languages present in their classrooms. Mindsets, models and methods have a major impact on how inclusive and accessible these classrooms can be and how well learners can use the language of instruction to access the content being learned.

In this chapter, we provide resources that can be used for different kinds of language users including for example, learners studying in their first language, learners studying in their second language, bilingual learners and learners who are speakers of other languages and are studying, for example, in an English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) classroom. Irrespective of the linguistic circumstances in the particular school or classroom, in this chapter teachers will find general resources for increasing their students’ access to language. It is important to bear in mind that the provided resources are designed to be used in multilingual classrooms. Another chapter will be devoted to language learners with special educational needs (SEN). That said, the provided resources must be adapted to the local, sociocultural context. Teachers need to take into consideration aspects within their specific contexts such as local identities, ideologies, values and priorities which may impact the ways in which the provided resources can be implemented in their classrooms. Some learning contexts, for example, may readily encourage multilingual mindsets while others may prioritise majority language usage and therefore would need greater guidance in adopting a mindset shift. Ultimately, teachers need to consider the language being used and the linguistic makeup of their classrooms—which are increasingly multilingual (Ortega, 2019).

Description of a structural disadvantage and how to address or prevent it

Content in the classroom is mostly delivered through language. In multilingual, bilingual and monolingual classrooms, learners have different levels of accessibility to the language of instruction. In order to make the subject matter accessible to all and to ensure that the classroom is fully inclusive, teachers need to relate explicitly to language. They can do this by (1) scaffolding language and by (2) defining content learning objectives while remaining aware of the role language(s) play in the learning process in general.

Scaffolding covers the systematic support for learners to carry out tasks successfully. The aim is to assist learners in moving, step-by-step, towards acquiring new skills. Scaffolding “is a special kind of help that assists learners in moving toward new skills, concepts, or levels of understanding. Scaffolding is thus the temporary assistance by which a teacher helps a learner know how to do something so that the learner will later be able to complete a similar task alone. It is future oriented and aimed at increasing a learner’s autonomy” (Gibbons 2015, p.16). In the terms of language education, scaffolding refers to breaking up language learning into manageable chunks. Scaffolding relates not only to vocabulary, syntax and grammar but also to semantic and pragmatic meanings as well as the prerequisite knowledge needed to access particular content. For example, learners reading about a snowy day in Finnish, might need to understand the difference between “tykky” (large chunks of snow) and “viti” (fresh powdery snow), a difference that in other languages might be marked by adding adjectives to describe snow. Similarly, learners listening to a cooking show about a common Middle Eastern food, “kubba” or “kibbeh” will need background knowledge about the more than twenty varieties of these meat-filled dumplings in order to understand the program. Scaffolding is important not only for language teachers but for all teachers who are guiding learners who are using language to access subject areas.

Defining both content learning objectives and language learning objectives is also an important part of language awareness pedagogy. Along with this, the teacher has to ensure that all learners have access to the language of instruction. A component of this is encouraging teachers to reflect on the prior knowledge needed within the realm of language and within the realm of content. Therefore, it is important to guide teachers towards asking and reflecting on how they are scaffolding language, the medium of instruction, to access content and also to consider how they are defining their content learning objectives to include language. These steps help ensure that all learners can access the subject areas being learned.

Key aspects

This chapter proposes three M dimensions (3m’s) for thinking around language and accessibility within multilingual classrooms:

- Mindsets, the epistemological or belief systems for grounding teaching and learning;

- Models, the structures and frameworks used for organising instruction;

- Methods, the concrete practices and techniques for making language more accessible for all.

Dimension 1: Mindsets

The first dimension discussed is Mindsets. This relates to the epistemological or belief systems teachers bring to the classroom. In our case, these mindsets specifically relate to multilingualism and language accessibility. Teachers need to be aware of the kind of language of instruction their students are familiar with and which other languages are present in their classrooms.They need to know which linguistic resources their learners bring to the classroom. Only then, is it possible to make sure that all learners also have access to the lesson’s contents. In general, classroom linguistic awareness means that teachers are conscious of the role languages play in teaching and learning. They pay attention to language use in different situations and support learners’ development by focusing on language and content skills interchangeably. As will be addressed in the subsequent section on methods, teachers who promote accessibility to language pay attention to language and content-learning objectives even if they do not explicitly adopt a content and language integrated approach (CLIL) to learning. They maintain a mindset that continuously bears in mind the role languages play in learning. According to previous research, language awareness significantly influences teachers’ beliefs related to multilingualism and teaching multilingual learners. Teachers who consider home languages as a resource and maintain positive beliefs about multilingualism are more likely to promote multilingual ideologies and inclusive practices such as translanguaging (Alisaari, Heikkola, Cummins & Acquah, 2019).

Multilingualism can be defined as “the use of more than one language by a community of speakers; a society in which different languages coexist side by side” (p.13). In contrast, pluralingualism refers to “an individual’s ability to communicate in a number of languages and switch among them to suit given circumstances, taking into account the trajectories and dynamic nature of language acquisition and use” (Council of Europe, 2001). In language education, the notion of plurilingualism “particularly highlights the relevance of learners’ language repertoires and the necessity to take these into account in teaching and assessment” (p.14) https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Mazkirut_Pedagogit/English/framework2020.pdf

Students’ who are multilingual demonstrate language varieties, which have been developed through prior instruction and also at home, through hobbies and during their free time. Students’ extracurricular and personal resources, especially their media environments, have a lot of learning potential irrespective of their subject or content. For example, students who follow football league fan sites or play online games in multilingual communities acquire particular words and phrases that can also be useful in formal learning settings (see Pitkänen-Huhta, 2019). As the above examples demonstrate, multilingualism and multisemioticity are key resources in multilingual classrooms in order to promote students’ thinking and expressing of their ideas (for further information see Duarte and van der Meij, 2018; Leppänen & Kytölä, 2017).

The above describes a mindset that recognizes the cultural and linguistic background of the learners. It can be meaningful when planning and implementing instructional choices. When teachers are aware of the learning potential found in, for example, students’ text worlds and media environments, they can better facilitate learners’ agency, and sometimes give learners tools for connecting the learning transpiring in formal classroom settings to the learning transpiring in non-formal settings. Teachers who, for example, acknowledge the linguistic competences present in their classrooms and design activities that build on their learners’ linguistic strengths can ensure that students are a part of the linguistic and cultural learning environment.

Another important aspect of mindsets is the relationship between students and teachers, which is fundamental and influences the pupils’ attitudes towards learning and knowledge (Rudduck, Chaplain & Wallace, 1996). Students will have difficulty learning from those they do not love (D’Amore & Fandiño Pinilla, 2015). Only when teachers obtain admiration from their students, can they promote enthusiasm and interest in the school subject (Petracchi, 1993). This is especially true for language learning where the content and the language are intertwined. Students generally do not decide the content being studied but can only build their knowledge based on their relationships with teachers and to the materials the teachers have chosen (D’Amore & Fandiño Pinilla, 2009). Therefore, students’ engagement depends on their personal relationship with the teacher and the ways in which the teacher mediates the content.

This is particularly relevant in multilingual classrooms where learners are accessing the language of instruction in different ways and from different starting points. The feelings and emotions they bring to the classroom, what the linguist Krashen (1986) referred to as “the Affective Filter” impact language acquisition. When learners feel anxious, embarrassed or afraid and exhibit a “high affective filter,” it becomes difficult for language acquisition to occur. In contrast, teachers who are invested in promoting wellbeing, including building connections with their learners and creating positive learning environments, will ultimately nurture more successful language learners (Mercer & Gregersen, 2020). Language teachers should be encouraged to promote positive emotions around knowledge as well as strong human relationships.

A final aspect of mindsets worth mentioning relates to beliefs, stereotypes and errors. Empirical studies such as those carried out by Donaghue (2003) and Borg (2019) have shown that teachers’ beliefs about language learning and teaching inform the mindsets they bring to the classroom. Therefore, it is worthwhile spending time reflecting on beliefs about teaching and learning in general and specifically as they relate to language.

One area where this is particularly important is around stereotypes and errors and specifically attitudes towards language “errors.” How can teachers approach errors in order to encourage and motivate learners? First, errors should be framed as “appropriate” and “inappropriate” rather than “correct” or “incorrect.” For example, if learners were writing a letter to the prime minister of their country, they would need to learn and practise formal letter writing including official and formal registers. However, these forms and structures would be quite “inappropriate” (albeit “correct”), if learners were writing an informal email to their new friend. Errors are very context dependent, and, in most situations, it does not matter if the grammar or syntax is “perfect.” The goal is usually to communicate something which the CEFR refers to as communicative language (Council of Europe, 2020). Therefore, the focus should be on whether the point the learner is trying to convey is being successfully communicated. Another important mindset shift is seeing “errors” in a positive light and as a source of information. Often, errors can provide insights into what the learner knows and can do with the language. For example, a language user who adds an “ed” ending to an irregular verb in the past simple (such as ‘fighted’), is showing awareness of the regular “ed” ending.

When considering errors, it is always important to think about the linguistic and cultural background of the learners, their prior knowledge and the home languages present in the classroom. These all have an impact on how learners grapple with and access language.

The way that teachers relate to language “errors” also connects to the perpetuation of stereotypes and the erroneous assumption that learners who do not use the language of instruction “correctly” or “perfectly” are less capable or knowledgeable. The distinction between receptive comprehension and linguistic production can again be useful here. All language users, and particularly plurilingual language users, have receptive linguistic knowledge, meaning they can understand many things being said to them before they can actively produce the same words and constructions. Moreover, they may be able to actively produce these same items in their home language but cannot yet do so in the language of instruction (for further discussion see Stubbs, 2002). As will be discussed in the section on methods, varying instruction and techniques and making use of multimodalities such as visual, non-linguistic representations can facilitate access to the content being addressed and provide opportunities for learners to successfully demonstrate their knowledge. Equally important is adopting a mindset that challenges assumptions around ability and “correct” language usage. Appropriate language usage depends on the social context and situation at hand. Teachers can openly discuss such constructions and differences while dismantling evaluation and judgements. Stereotypes sometimes used to describe variations of language (or those that are considered “nonstandard”) include “uneducated, improper, impolite and bad” (Crovitz & Devereaux, 2017). Such presuppositions can have detrimental effects on students’ evolving identities both as learners and language users. Encouraging teachers to reflect on their attitudes and biases towards language differences is a critical part of the process of debunking stereotypes and validating all learners.

Dimension 2: Models

Example

“UDL is about thinking about our learners in terms of variability instead of ability and disability. It is about the different ways that our brain learns. UDL breaks up how our brain learns into three strategic networks – UDL principles – which we can use to engage students in their learning. These principles are engagement, representation and action and expression. If you think about these principles in terms of the learning in your classroom, I can give you some really nice examples. In terms of engagement, you can think about bringing in the students’ first language where they can see themselves in the classroom. If you ask them what their primary word is for a word you are teaching or for a word you taught yesterday, that is engaging them in the lesson and is bringing in that contextual aspect to the learning as well. If you think about representation, this is about the content you are delivering to the students and how they are able to access that content. If you are teaching new words and you just give the words on a worksheet with some sentences for the students to fill in, they are not necessarily going to be able to do that if they are not able to access the new words in different ways. So another way could be through audio where the words are phonetically spelled out for them. Or another way could be through visual signs. I was walking through the corridor today and the classrooms here have subjects written in Italian and German. I do not speak Italian or German. So in most rooms I don’t know what subjects are being taught. But in one door, they had Italian, they had German, and then they had a music note. I know music is happening in that classroom. So that is an example of representation in terms of action and expression. It is about understanding the goal. It is focusing on that accessibility, knowing your goal and making sure that there are no barriers to the students demonstrating that they have achieved the goal. […] That is UDL in a very short nutshell and I hope some good examples of how it can be used to foster language accessibility.”

Margaret Flood, Assistant Professor, University of Maynooth (Ireland)

The variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds of students describes nowadays best the fact that every teacher is actually also a language teacher. The diverse needs of learners have to be taken into account despite the school subject. For ensuring language accessibility for all learners, the universal design for learning (UDL) framework works as a pedagogical tool in order to assess classroom activities (Connell et al., 1997). Instead of the speaking abilities and disabilities of learners, the different ways that our brain learns can be observed and used as resources of learning. Our brain learns into three strategic networks: engagement, representation and action and expression. These are UDL principles, which we can use to engage students in their learning. We present in the following section four models that are based on the UDL principles. The PID model, thinking skills relating to the linguistic competences, languaging in mathematics, and arts-based meaning making represent the models that facilitate the learners to use their various linguistic capacity also for content learning.

The core of student-centred language pedagogy is acquaintance of students including their hobbies, reference groups, reading histories, and studying techniques. Systematic classroom observing in language settings is a part of teachers’ competences and a part of teacher professionalism, it is something that can be learnt (Stürmer & Seidel, 2015). When the planning process of instruction begins, we can encourage teachers to explicitly reflect on the prior knowledge needed with respect to language and content issues and, after that, to define the learning objectives. In their reflection process, teachers can use a framework entitled the PID model (perception – interpretation – decision-making).

The PID model encourages teachers to pay attention to both language and content issues affecting students in their classrooms. In the first phase, the perception phase, teachers’ attention should focus on a specific component of language and interaction or other content present in the classroom. Then teachers interpret their perceptions based on their experience, knowledge, and familiarity of the group. In the last phase, the decision-making phase, teachers come to conclusions about the activities being implemented in the classroom. The activities arise organically based on students’ situational interests which, ideally, harnesses motivational aspects of learning (Swarat, Ortony & Revelle, 2012).

Even for experienced teachers, the PID model gives tips to get in students’ engagement (Stürmer & Seidel, 2015). For example, students may not appear to be involved in the lesson, although they are actually doing intensive thinking work. Therefore, practising observation is needed to notice students’ engagement. Further, co-teaching is a great opportunity to maintain and to develop observation skills. When co-teaching, both teachers’ observations can be compared. It is critical to notice that students are unique with respect to their linguistic and learning resources. The observation process needs to be carried out by teachers at both the group and individual levels in order to enable teachers to recognize learners’ strengths and to develop learning objectives related to linguistic competences.

Students’ thinking work is closely connected to linguistic competences. For example, the ways in which learners work with text sources is intimately related to thinking skills. According to Lipman (1988), good thinking means critical reasoning, which includes the thinking skills of estimating, evaluating, classifying, assuming, inferring logically, grasping principles, noting relationships among other relationships, hypothesising, offering opinions with reasons, and investigating and making judgements with criteria. All of these skills contain linguistic elements which some learners grapple with. Further, multimodal text interpretation and production requires transferring from one textual mode to another (from audio to visual etc.), which can be challenging to students, while the meaning-making systems use different semiotic resources. What teachers need to do is to clarify the connections between actual thinking and learning processes and their connection to linguistic choices. Scaffolding is critical so that the linguistic elements can support students’ thinking processes.

Teachers can combine language with content in several ways (see Bunch, 2013). For example, in mathematics teachers can use languaging when there are expressions of mathematical thinking through language in the classroom. In this case, drawings, diagrams, body language and other multimedia forms of expression can be a part of the instruction. For example, learning geometry in investigating tessellations gives learners many multimodal resources for content learning despite their linguistic background (Hähkiöniemi et al., 2016). In this way, teachers can combine the content learning and language learning objectives through careful planning of the components of the learning environment (see Hähkiöniemi et al., 2016).

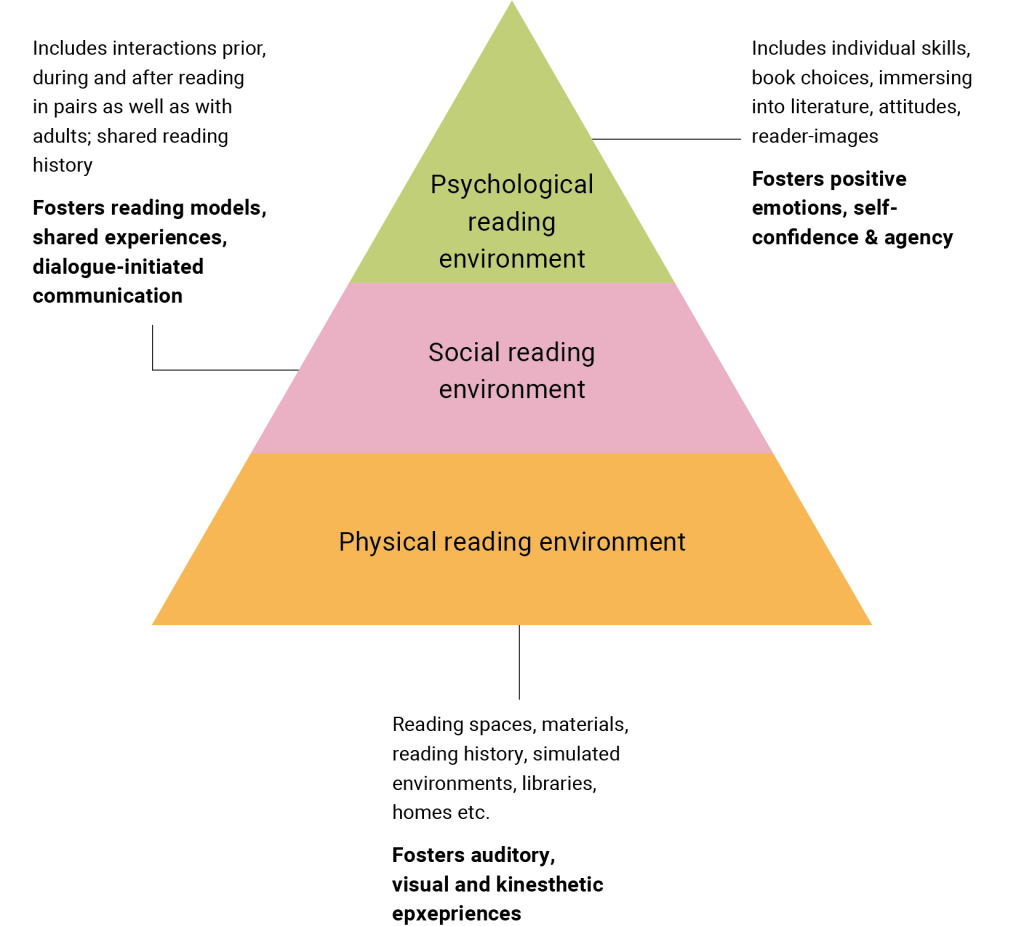

Arts-based meaning-making provides ways to activate multimodal expression and thus promote multilingualism as a resource of learning. It is based on the StoRE® – Stories make readers programme, which Aerila and Kauppinen (2017) developed together with Finnish teachers. The arts-based meaning making lies on the ASM model for literacy learning. There are 3 cornerstones of the ASM model for reading and writing literacy as follows:

- A refers to the amount of reading and also enough time for reading. Any kind of text can be the material of reading.

- S refers to the suitability of text material for the reader. Suitability includes reader’s interest in topics, popular genres, language choice etc. as well as adequacy to the level of reading skills.

- M refers to meaningfulness to the reader so that the action around the texts makes sense to them, and the reading environments and activities are meaningful to them rather than repeating and rote reading without meaning. Especially arts-based activities have inspired the students to literacy learning.

The ASM model as part of the StoRE®-programme can be applied to various linguistic and age groups of the learners with diverse reading and writing skills (Pathways-training | Polku-täydennyskoulutus). The programme develops academic literacy skills as well as aesthetic and emphatic stances towards reading, where readers focus on the experiences and emotions they have with a text. The ASM model lies in the reading setting consisting of physical, psychological, cultural and social factors (Brooks, 2011; Figure 2). The arts-based meaning-making activities can be the part of all these reading environments so that all capacity of expression by students is largely promoted.

Figure 2: The elements of reading environment in the ASM model for literacy learning

The following example concerns the Finnish school applying language awareness pedagogy in science. It concretely shows how the ASM model is used in transversal learning combining biology and domestic science in language learning settings. In one school, there was a greenhouse in the school yard, where students could grow plants and also different types of herbs. They learned what various herbs need in order to grow properly; namely oregano needs different soil than basil. As the herbs grew, the students made notes about the plants’ properties and collected them on a table. The notes consisted of pupils’ observations via senses, for example how the herbs smell, what they look like, etc. Vocabulary in the field of biology related to observations and phenomena concerning the plants’ growth was learnt at the same time. Furthermore, the students searched for information about the medical purposes of the herbs as well as the herbs’ history and prevalence globally. After that, they created posters that related to all of the content and material learned. At the end, the students made a menu in which dishes were spiced with herbs.

Picture 1: Students’ poster representation of Basil.

In this task, the linguistic as well as other multimedial meaning-making resources were diversely used in the classroom, while content information was collected and defined via various modalities. In addition, students learned Latin words when they searched for information about how herbs can be used for medical purposes. They also became familiar with meaning making through the visual mode of posters and other visual and graphic forms. Students reported that the learning task was meaningful and also useful for them. The choices of layout like the position of each element were an authentic learning experience for them. The teachers noticed how important it was to give multimodal meaning-making tools for learning in the multilingual classroom. In that way, each student could choose the tools which they found to be suitable for their situation and purposes.

In this task, the linguistic as well as other multimedial meaning-making resources were diversely used in the classroom, while content information was collected and defined via various modalities. In addition, students learned Latin words when they searched for information about how herbs can be used for medical purposes. They also became familiar with meaning making through the visual mode of posters and other visual and graphic forms. Students reported that the learning task was meaningful and also useful for them. The choices of layout like the position of each element were an authentic learning experience for them. The teachers noticed how important it was to give multimodal meaning-making tools for learning in the multilingual classroom. In that way, each student could choose the tools which they found to be suitable for their situation and purposes.

Afterwards, the students who have studied herbs in the greenhouse organised a Herb Path for younger students with special needs. The older students planned and prepared activities that consisted of several stations where their classmates learned about different herbs. The older students guided the younger ones to smell, taste and recognize each herb and put their notices on the table. At each station, they searched for words and information about herbs together. At the end, there was common discussion about herbs and the learning experiences.

Dimension 3: Methods

Employing innovative techniques, methods and approaches can help ensure learners have access to the language used for learning in the classroom. There are many methods in terms of tools teachers use in the classroom to make language more accessible to learners, for example, cooperative learning, peer tutoring, laboratories, and open-space learning. Methods and techniques abound. However, it is critical to bear in mind a fundamental principle: no one method is superior or best for meeting the needs of all learners. Rather, teachers should make use of and alternate different teaching methods, thus increasing the possibility that students with different personalities, characteristics and learning preferences are involved in the learning process. Even if it constitutes the most recommended method at the time or is based on “traditional” teaching, focusing the teaching-learning process on a single teaching method is almost always a source of error (D’Amore & Fandiño Pinilla, 2015). Instead, what is important is to consider the difference between teacher-centred methods and pupil-centred methods. In the first case, the focus is on the teacher, who can implement a range of teaching methods. One example is a frontal lesson. When it is the main method used and it assumes the structure of a purely transmissive lecture where the teacher explains and students listen and take notes, without moments of elaboration and feedback, the students mainly play a passive role (Trinchero, 2013), even if they could learn something. In the second case, in pupil-centred methods, students are the protagonists of the learning process. They actively experiment and act, constructing their own learning under the guidance and supervision of the teacher. This approach can include, for example, active workshops, cooperative or group learning and learning technologies. In particular, methods based on technology can help learners to use language to access content, using different modes and modalities for scaffolding language. Learning technologies can support students’ learning in different ways and reinforce their motivation. Educational technology increases learner agency and helps further motivate searching for information, knowledge and for developing texts for different purposes.

Another method for fostering access to the language embedded in specific subject areas is Content-Based Instruction (CBI) or Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) (Wiseman, 2018). Such approaches involve teaching certain school subjects in a language other than the learners’ main language of school instruction. In these types of lessons, the focus is on the topic or school subject, and the students access the content using the language they are learning. In particular when adopting CBI, it is important to define both content learning objectives and language learning objectives so that all learners can access the language being used (Wiseman, 2018). CBI is a helpful method and an important example for ensuring language learning for all, but before planning and simply applying this strategy, it is necessary to consider the relationship between learners and their school subjects, in terms of pleasure and displeasure to learning a particular school subject (Ghaith & Shaaban, 2005). If students like the subject but they do not like the language used in CBI, they might end up not liking the subject as well. By contrast, using this method might be helpful for learners who love languages, helping them to approach the school subject positively. It is always better to consider students’ relationships and feelings towards the topic being taught in the classroom. Teachers can take into account the affective aspects that can be interposed, positively or negatively, between the students and the subject. These aspects have repercussions on students’ attitudes towards the language used and the school subjects, in terms of success or failure in a language acquisition process (Balboni, 2012; Freddi, 2012).

Another useful method is “Task-Based Language Learning” (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011) which is an approach to language learning where learners are given an authentic and interactive task to complete. In order to complete the task, learners need to communicate with each other. Every student has a part in completing the task. A nice example is the creation of a weekly activities chart where each student writes down the activities they do in a weekly calendar. For example, in the column for Monday, a student named Jack might write “every Monday Jack plays basketball.” The task is complete only when every student in the group has written their activities. This ensures that all students are taking part, but they can help and support each other in filling out the weekly activities chart (for further information see Larsen-Freeman and Anderson, 2011).

A final method for fostering language learning for all is encouraging translanguaging in the classroom. Translanguaging can be defined as an approach or method that considers multilingualism at its core and uses learners’ full linguistic repertoire – the home language and the language of instruction. Methods based on translanguaging relate to language and content competences and include planning activities in two or more languages. This approach is learner-centred and endorses the support and development of all the languages used by learners. Pedagogical translanguaging can be applied in language and content classes and it can be valuable for the protection and promotion of the non-majority languages present in the classroom (for further discussion see Cenoz and Gorter, 2022). In this way, it is possible to include all students in a respectful and authentic manner.

This chapter addresses three dimensions for making language accessible for all: mindsets, models and methods. A final point of consideration is that the provided resources for content learning must be adapted to specific contexts. Classrooms as well as curricular expectations vary, and it is up to teachers to modify and apply their practices to local contextual needs.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions

- How do you take into consideration pupils’ different starting points in the language of instruction? What tools or strategies do you use?

- How do you build on pupils’ prior content knowledge when introducing new subjects and topics?

- How can you preserve the cultural and linguistic background of your students?