Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

‘To build up a Community’ – Collaboration with parents

Assimina Tsibidaki; Linjie Zhang; and Nico Leonhardt

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“I have many, many examples where we succeeded with parental involvement, but I want to give you one example. I have worked in a community that is still very nomadic, and they keep cattle, and it’s important for everybody in the family to participate in cattle grazing and other chores. So, the school was having parental meetings, and they were having these meetings at the school. The school reported to us that they have tried to bring in parents on different days of the week, but they always had to cancel or postpone the meetings because the parents wouldn’t come. So, when they approached my research team, asking how they should handle the issue, we asked them, how about doing this meeting in the community, which is about 50 kilometres from the school, and asking the parents what time would suit them for the meeting? The very first meeting they held in the community, they had almost 100% attendance (except for those who had responsibilities of going to find the lost cattle and so on), because the parents decided on the time of the meeting, felt at home in the community and felt free to speak in their language. The school reported to us that it was the first time that they had this kind of attendance and this kind of involvement. So, I think it is very important to first consult with the parents who you want to involve and to give them a choice about the time and how the meeting should occur. In my country, “parents” are not only the biological parents of the learners. Parents can be community members; a parent can be in the form of an uncle; they can be older siblings and so on. They say that if they had this kind of meeting at the school, they wouldn’t even have a place big enough to host the parents. But in the community, everybody attended because you qualified to be a parent. That’s my story.”

Initial questions

- Why is collaboration between parents and schools essential in fostering an inclusive educational environment?

- What are the main barriers that prevent effective parent-teacher collaboration, and how can schools address them?

- How do cultural and socioeconomic factors influence parental involvement in their children’s education?

- What strategies or models are discussed in the chapter to enhance meaningful partnerships between schools and parents?

- How can schools shift from a teacher-centered approach to a more community-based model of collaboration with parents?

Introduction to Topic

Collaboration with parents constitutes a process that requires a personal commitment based on a clear rationale and a high level of collective and personal self-efficacy. This commitment, honours the diverse structures and backgrounds of the families, employs real communication skills, provides curricula and problem-solving solutions that are aligned with the parents’ and students’ goals and occurs within a parent-driven relationship (Porter, 2008). Successful home-school collaboration is more about how individuals share their work, and it is characterised by voluntariness, mutual goals, parity, shared responsibility for critical decisions, joint accountability for outcomes, and shared resources (Friend & Cook, 2017).

This chapter aims to explore the importance of teacher-parent collaboration in inclusive education. In particular, it highlights what it means to collaborate, working with parents, and the key barriers and risks in collaboration. Finally, it seeks to provide key principles and examples of effective and efficient home-school collaboration.

It is worth mentioning that this chapter is based on the philosophy of inclusive education, focusing on human relations, and its main goal is to create an inclusive school and an inclusive society.

Key aspects

The meaning of collaboration with parents

The term “collaboration” is of high value and quality. A common definition of collaboration is a partnership to achieve a common goal or a set of goals. It refers to a reciprocal dynamic process that occurs among systems, schools or classrooms, and/or individuals who share decision-making toward common goals, solutions and decisions in order to support student success (Cowan et al., 2004; Gerdes et al., 2022; Minch et al., 2023; Witte et al., 2021). Collaboration is characterised by voluntary, co-equal, and authentic partnerships between parents and teachers (Cox, 2005 as cited in Minch et al., 2023).

The importance of good parent-teacher collaboration has been well documented. More specifically, promoting collaboration in education improves children’s academic and social outcomes, both in early education and beyond (Castro et al., 2004). When collaboration is focused on improving the well-being of children and adolescents, decades of research show that children benefit. Benefits include improved academic, social, behavioural and mental health outcomes (Witte et al., 2021). The collaboration continuum describes the three dimensions of co-work as cooperation, coordination and collaboration (McNamara, 2012).

Collaboration with parents constitutes a process that requires a personal commitment based on a clear rationale and a high level of collective and personal self-efficacy. This commitment honours the diverse structures and backgrounds of families, employs real communication skills, provides curricula and problem-solving solutions that are aligned with the parents’ and students’ goals and occurs within a parent-driven relationship (Barker & Harris, 2020; Jorgenson, 2023; Porter, 2008). Successful home-school collaboration is more about how individuals share their work, and it is characterised by voluntariness, mutual goals, parity, shared responsibility for critical decisions, joint accountability for outcomes, and shared resources (Friend & Cook, 2017).

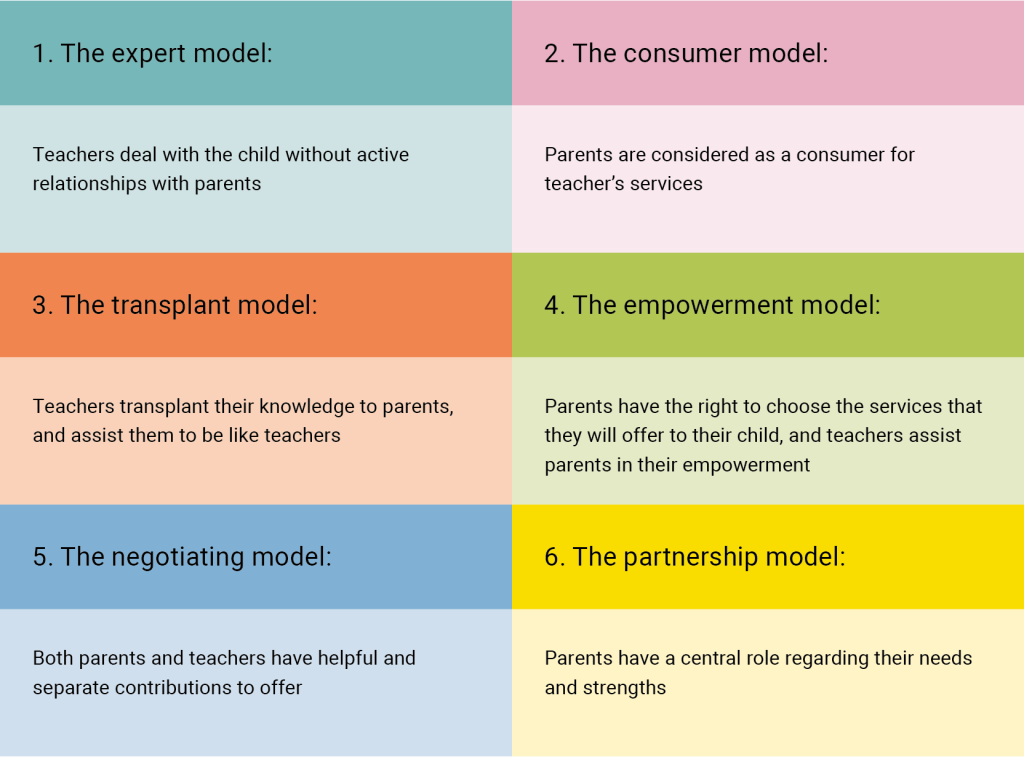

Various theoretical models for fostering cooperation and collaboration between parents and educators are delineated and scrutinised within the academic literature, utilising a range of adaptable frameworks (Sadownik & Višnjić Jevtić, 2023). Among the most prevalent models are (Figure 1):

- The expert model portrays parents as passive recipients of professional expertise.

- The transplant model endeavours to harness parental involvement by viewing parents as executors of received expertise and guidance.

- The consumer model positions parents as rational and well-informed decision-makers, while educators serve as purveyors of information and facilitators of various educational options.

- The empowerment model aims to promote collaborative decision-making and upholds the right of educators to create the necessary framework (Dale, 2008).

- The negotiating model promotes a partnership characterised by shared responsibilities. This model emphasises negotiation to reach mutual decisions and resolve any disagreements that may arise. Negotiation may result in a consensus or disagreement, and the model advocates for adaptable roles and mutually agreed-upon outcomes. It underscores the valuable and distinct contributions of both parents and educators, asserting that their differing perspectives are essential for fostering successful collaborations that yield positive outcomes for the child (Abed, 2014).

- The partnership model underscores the importance of collaborative decision-making and shared accountability (Hornby, 1989; 2011).

These models address diverse aspects and dynamics inherent in parent-teacher relationships, underscoring the necessity of tailoring approaches to suit specific contextual nuances and requirements (Sadownik & Višnjić Jevtić, 2023).

Figure 1: The models of parent-teacher collaboration

Aiming to meet the increasingly demanding tasks of parents as well as the complex requirements of school learning, a common understanding of collaboration is needed (Walper, 2021, 343). In the sense of inclusive education, it is about the design of inclusive learning and living spaces for pupils and a networked cooperation of many actors, especially parents and teachers. To reach the students, to get to know their situation, their lifeworld’s, we have to see parents or families as partners in education (Leonhardt et al., 2024, in press). We have to integrate parents into the school communication and relationship culture (Werning & Avci-Werning, 2021). An inclusive understanding of school and education not only ties school success to an increase in performance but also aims at the well-being of the students. This requires a systemic view of schools and students. This means that collaboration is not a bilateral negotiation, but rather the building of a community that includes teachers, parents and the social space of the school. This process is challenged by various aspects (see Section 3). Above all, however, it is to recognise the school as a powerful system (Leonhardt et al., 2023; Liebel 2020), especially in order to take into account the mentioned and necessary exclusion analysis.

The idea is not just to bring students with differences into the system, it is more a question about educational justice from a human rights-based perspective. In this sense, inclusive processes are always connected with a continuous determination of the relationship between inclusive and exclusive aspects (Oldenburg, 2021). For that, it is important to always analyse different kinds of exclusion also.

We must think about different kinds of aspects of school (like classes, social interaction, pedagogical relations…) and if they are really inclusive. We must also think about this for the parents. In this inclusive understanding, school is like a learning organisation and so it is important to integrate this thinking into school development processes.

International studies show that parents play a significant role in school learning success (Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003; Jeynes, 2005, 2007, 2011; Kruschel et al. 2023; Textor, 2009,). However, it is not so much ‘passive’ or formalised formats of parent collaboration that lead to student success (Pomerantz et al., 2007). Rather, the active participation of parents is central to creating successful learning environments and inclusive educational spaces for students (Sacher, 2013; Schwaiger & Neumann 2011). This is therefore central to the design of inclusive school development processes. Also, in relation to collaboration with parents, it is important to approach different levels together in order to uncover and reflect on possible exclusion processes.

Different backgrounds of parents and how these influence the collaboration

Research shows that parents, despite all their differences, share a multitude of perspectives and commonalities (Müller, 2014). Many parents are mostly satisfied with inclusive forms of learning if the necessary equipment is provided (ibid.). However, when it is about inclusion, it is not just the students who are very diverse, the parents are also. There are more parents with many different backgrounds. At the same time, there are many connecting aspects with parents that need to be considered. The ‘old’ ways of thinking about parents or collaboration doesn’t fit anymore, especially in inclusive schools.

To think teachers just must inform them isn’t enough. The lifeworld and the biography of families are very different, so we need to create different ways of working together. These different family backgrounds have a huge impact on the types of parent collaboration. For example, research shows that social background has an influence on successful education (see below). What is their experience and connections to school? What do they know about the school system? Those are just some of the questions that are very much related to teacher-parent collaboration. Also, other kinds of experience and dimensions can be very important in this case, for example, cultural, religious background or experience in relation to the sexual orientation or experience of disability.

As the example from Namibia at the beginning made clear, in some cases it is not exclusively the birth parents who are responsible for the students. It can also be family members, guardians or other community members. There is a lot of diversity to be considered in this regard also. Furthermore, in the sense of dialogue-based cooperation, it is important not only to keep the different life worlds of the parents in mind but also to critically and reflectively consider the previous experiences of the teachers. Expectations, ideas of normality, prejudices, and false ability requirements in the sense of classist or ableist attributions can decisively shape the actions within the cooperation (see also the → chapter ‘Teacher Habitus’ or ‘Labeling‘).

In the following, we would like to take this broad understanding of two dimensions (social/cultural & disability) as examples in order to show the influence of different backgrounds.

First dimension – social, cultural

Several studies indicate that there is an imbalance in parental participation even within the same school (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Lareau, 2003; McNeal, 2014). Disparities in parent inclusion and involvement are evident based on factors such as race, ethnicity, social class affiliations and students with and without special needs (Harry & Klingner, 2014; Hill & Tyson, 2009; Lareau, 2011). Additionally, when examining schools located in American low-income neighbourhoods and communities as the primary focus, researchers have frequently observed that parental engagement in school-centric activities and programs tends to be sporadic, minimal or entirely absent (Hill & Tyson, 2009). One of the reasons for this is that these parents are “not sufficiently perceived with their fears and concerns” (Paseka & Killus, 2021: 180, translated).

The existing research on parent involvement in low-income school communities highlights various intricate sociocultural and political factors that can contribute to limited parental engagement in activities initiated or centred around the school. The Corona period has made visible the dependence and linkage to family resources, as well as the close connection to the perpetuation of educational inequalities (Huebener et al., 2021: 182). Studies have shown that disparities in parental participation among different socioeconomic groups could be attributed to the conflictive relationships and interactions between teachers and low-income parents (Hill & Tyson, 2009; Lareau, 2013). These interactions are frequently marked by conflicts that stem from disparities in societal status and power (Delgado-Gaitan, 2004). Scholars in the field noted the prevalence of school-centric and ethnocentric communication patterns within the interactions between teachers and parents, which can further exacerbate these conflicts (Hannon & O’Donnell, 2022; Henderson & Mapp, 2002). Additionally, recent research has raised questions about the extent to which some low-income and ethnic minority groups could engage in institutional processes shaped by dominant cultural norms and frames of reference (Warren & Mapp, 2011). Moreover, Henderson and Mapp (2002) emphasise the critical role of recognising and addressing racial and cultural issues within educational institutions. Failing to acknowledge and address these issues, especially when there are disparities in treatment and opportunities, can reinforce racial and cultural divisions and boundaries between schools and families (Warren & Mapp, 2011). Parents in challenging life situations are less recognised as a resource and thus less actively involved in school (development) processes. At the same time, they themselves have fewer resources to become (self-)actively involved. This problem becomes even more acute in challenging neighbourhoods since the perception of students and parents in these areas tends to be more problem-oriented than appreciative (Fölker & Hertel, 2015). At the same time, it is evident that teachers are mostly middle-class-oriented, which can lead to difficulties in comprehension and a lack of habitus sensitivity. (see → chapter Teacher Habitus )

In low-income, ethnically concentrated school communities, the concept of parental engagement seems to be both constrained and constraining. It is constrained because of the fact that it is mostly defined and applied by educators within a relatively narrow, yet significant, school-centred framework. Its constraining aspect arises from the fact that parents often perceive and define the significance and roles of parental involvement beyond the confines of the school, whereas teachers’ predominantly technical interpretations suggest that the term might only capture a fraction of their understanding and expertise regarding school-family interactions.

When exploring the dynamics of role construction involving both educators and parents, parents and teachers in low-income school communities often find themselves in conflicting roles, subsequently influencing the extent of parental involvement in educational institutions. According to Pantić and Florian (2015), educators’ roles are typically characterised by specificity and limitation, which promotes a more objective and impartial assessment of children’s behaviour, development, and readiness. This perspective stands in stark contrast to the broader and boundless viewpoint of parents, who tend to perceive each child through the lens of their personal experiences and circumstances (Henderson & Mapp, 2002). In summary, these marked disparities are believed to engender discontinuities, disconnections, and cycles of blame between families and schools, with detrimental repercussions for children, families, and educators alike (Epstein, 2018).

Second dimension – Special Educational Needs-Disability (SEND)

Example case

“I work with children with severe kinds of disabilities and difficulties. If I need some kind of successful example, it should be to build an educational network which involves us as the school. It can involve all kinds of actors that are around the child or the young people, such as teachers, family therapists and doctors etc… We need to talk about this because when we talk about disabilities, it is a really complicated situation. We must have functional communication with all of these actors. I truly believe that school can play a central role in this. It is easier to have a school in which families and therapists can go inside and have a moment to dedicate to a particular child or a particular kind of problem.”

Francesca Mara Santangelo, teacher for special needs education, Italy

Collaborating with parents raising children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) is essential. The collaboration process brings educators, parents, and other specialists together to support children and adults with SEND. The goal of the collaboration is to ensure that students with SEND have access to the resources and supports they need to succeed in school and life (Saikat, 2022).

It is important to note the literature confirms a range of benefits associated with effective inclusive education (Sharma et al., 2022) and home-school collaboration for students with and without SEND (Hehir et al., 2016). Some parents of children without SEND may object to their children sharing a classroom with students with SEND, believing that their difficulties or needs could impact the learning of other children (Cardona, 2006). However, parents gain knowledge about inclusive education, they may change their perspectives and become advocates for inclusion (Kalyva et al., 2007). Moreover, they recognise the positive effects on their children without SEND, such as improved academic outcomes and greater acceptance of diversity (Hehir et al., 2016).

In addition, when working with a family raising one or more children with SEND, we need to follow a basic principle, that every family is unique. We may come across families that have one or two parents with a disability and/or one or more children with a disability. Disabilities vary in type and severity, so in every process of working with the family, we should have an individualised and holistic approach (Dale, 2008; Seligman & Darling, 2007). Collaboration with parents raising children with SEND is child-centred, providing parents with a voice on placement services. Both parents and children participate in the decision-making. Parents who are the most familiar with their children can contribute to a partnership by sharing information about their children. However, before they openly collaborate, they must trust the team (Bennie, 2023). Parents’ collaboration is not only beneficial for children there are also possible gains for all parties (Saikat, 2022):

- Parents increase interaction with their children with SEND, become more responsive and sensitive to their needs and more confident in their parenting skills.

- Educators acquire a better understanding of families’ culture and diversity, feel more comfortable at work and improve their morale.

- Schools, by involving parents and the community, tend to establish better reputations in the community.

The key components of effective collaboration in special education include:

- A common understanding of the goals of the student’s Individualised Education Program (IEP).

- Open communication between all members of the team. This includes both verbal and written communication.

- Respect for each other’s roles and responsibilities on the team.

- A willingness to work together towards the best interests of the student with SEND (UNICEF, 2014).

Main barriers to parent-teacher collaboration in inclusive education

In the context of parental co-operation within education systems, there are numerous barriers and challenges that can vary significantly from country to country. These differences are often rooted in distinct historical and cultural backgrounds that shape each education system.

Please be aware

Despite the strong theoretical and research acknowledgement of the benefits of family-school collaboration, there are many challenges to putting this into practice (Hornby & Blackwell, 2018; Minch et al., 2023). The barriers related to all parties involved. The various barriers to collaborating with parents can be considered as follows (Hornby & Blackwell, 2018; Minch et al., 2023): Societal factors (which influence the functioning of both schools and families), individual parent and family factors, parent-teacher factors, and child factors.

Common barriers from the parents’ perspective can include:

- Parents’ work demands and lack of time.

- Parents feeling overwhelmed and outnumbered.

- Language, cultural or socioeconomic difference.

- Parent attitudes about the school.

- Prior negative experiences with schools.

- Lack of parent education to help with schoolwork.

- Shared or complicated custodial situations.

- Limited access to technology.

- Unequal power relationship between parents with low status and mainstream cultural values.

Common barriers from the teachers/school perspective can include:

- Limited school resources.

- School policy versus reality.

- Inflexible work schedules.

- Staff attitudes toward parents.

- Unspoken expectations about family engagement.

- Lack of parental understanding.

- Language differences between parents and staff (IES – NCES, 1998; Parentpay Group, 2022; Understood, 2019).

- Teachers’ lack of ownership, withdrawal and scepticism caused by exclusion from schools’ program development

Teachers lack ownership of school reform initiatives in part because they are excluded from planning those programs. As a result, they are less likely to become involved and believe that new reform initiatives about collaboration will result in real change (Datnow, 2020).

- Teachers’ negative attributions caused by the school’s use of incentives

Incentives for parent involvement could lead to the negative effect that teachers feel caught in a value conflict. Even when parents get active in their children’s education, incentives drive teachers to believe that parents do not fundamentally value education (Henderson & Mapp, 2002).

Barriers from the children’s perspective can include:

- Children may have negative attributions of parent involvement which could lead to difficulties when establishing positive connections between teachers and parents (Loughran, 2008).

While parent-teacher collaboration has numerous benefits for all (parents, teachers and children), the literature has identified a variety of beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that act as barriers in collaboration in inclusive settings. Research has also revealed many facilitators of teachers-parents collaboration that we will discuss in the next section.

Core principles for effective school-family collaboration in inclusive settings

Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1997) suggested that parents usually become involved in their children’s education when three necessary conditions and preconditions exist:

- Parents have developed a parental role that is affirming to parental involvement in education.

- Parents have a positive sense of efficacy in helping their children succeed,

- Parents perceive positive opportunities and invitations to become involved in their children’s school.

The following suggestions might be helpful in achieving these three conditions (Turnbull et al., 2015):

- Communication: Teachers and parents communicate openly and honestly in a medium that is comfortable for the family.

- Professional competence: Teachers are highly qualified in the area in which they work, continue to learn, and communicate high expectations for students and families.

- Respect: Teachers treat families with dignity, honour cultural diversity, and affirm strengths.

- Commitment: Teachers are available, consistent, and try to ensure individual needs of the learner are successfully met.

- Equality: Teachers recognise the strengths of every member of a team, share power with parents, and focus on working together with families.

- Advocacy: Teachers focus on getting the best solution for the student in partnership with the family.

- Trust: Teachers are reliable and act in the student’s best interest, sharing their vision and actions with the family.

Loughran (2008) suggests that due to the diversity among parents and to best communicate with each parent, it is necessary to:

- Communicate succinctly and clearly. Organise your thoughts ahead of time and review written messages.

- Make clear to each one that he or she is respected and his or her participation is encouraged.

- Be flexible, encouraging working parents to participate actively and be involved when and where possible.

- Secure multiple methods of two-way communication: email, telephone, postal mail, face-to-face communication and apps (for example, WhatsApp, REMIND, Blackboard, ClassDojo, etc.) (Gerdes et al., 2022).

Lawson (2003) argues that schools play an important role with regards to building up school-community partnerships. Schools can:

- Create a cooperate-friendly environment in which parents, children and teachers are all involved and share equal power as well as access to resources, so that they can positively engage with each other.

- Help to build consensus on cooperation between families and teachers.

- Provide additional support for disadvantaged families as a social service referral agent.

Finally, think of the TEAM acronym (Bennie, 2023):

T – Together E – Everyone A – Achieves M – More.

Selection of some good practice examples for successful parental collaboration

Example Case – “I also have many examples. One that I can share with you would probably be about one of many Arabic families who came to Germany in 2015. I’ve been accompanying these people from day one until the present day, and I remember the first contact was difficult because they had a lot of expectations. There was a language barrier that we needed to overcome and there were cultural differences also. It was very difficult for me at first to establish a relationship because we had to work with translators. I found this very distracting because you never have direct communication between two people, it is always with somebody in between, no matter how nice they may be. The families started learning German and I started learning Arabic f. It was a lovely experience because I would so to their home for a coffee and try to learn Arabic. Not only was a learning the language but I also seeing a different context by getting an opportunity to see the families background and establish a different type of relationship with each other. It was really nice for them to teach me Arabic because, of course, I made a fool of myself because I did not speak Arabic proficiently. Of course, it is still something that we can laugh about together. In Arabic culture, they were very apprehensive to speak German, because it is often customary to laugh at you if you make mistakes. They found that if they made mistakes when speaking German to me, I would not laugh, and I would not judge. That was sort of the foot in the door to establishing this relationship. That relationship became really important in teaching them how to get by in the German system by explaining to them how the system works and what our values and traditions are. I also showed them what things they need to abide by. And it’s not just about telling somebody you must do this, and you must not do this, but for them to truly understand how it works, which is important for them to be successful. It takes many, many years to understand all of this. I recall a lot of situations when they were very overwhelmed by the German paperwork. You feel very vulnerable when you are in a different country, and you cannot read or write their language, and you don’t know what to do or you have to ask for help. They would ask me, and I would help them and I tried to establish some kind of system with them” (Chris Carstens, secondary teacher, Germany).

There are many successful examples of collaboration with parents. Some have already been presented at the beginning of this text. In order to gain further insight, we now want to present more good practice examples. However, these examples have always been developed in a specific individual and social context. The following are some examples of best practice to give the basic ‘idea’ of collaboration.

Examples of building ‘bridges’ between school and parents

In the context of appreciative and successful parental cooperation, the extracurricular programme of the so-called ‘bridge builders’ in Basel (Switzerland) was conceived (Leonhardt & Kruschel, 2023). The main questions that were addressed for this project were, how can we reach more parents and how can a dialogue be established and maintained?

The project has a goal-oriented effect on three levels:

- Parents: Strengthening and empowerment through information and resource-oriented support

- Children: Increasing equal opportunities through improved parental cooperation

- Professionals: Sharing background knowledge and strengthening intercultural competence.

The trained ‘bridge builders’ (https://www.heks.ch/was-wir-tun/brueckenbauerinnen) all have experience in intercultural mediation and/or in parental co-operation. Together they speak approximately 16 languages, have diverse cultural backgrounds and are themselves very familiar with the social environment. The target groups are parents with children in the age of pre-school to primary school. Contact is usually established through recommendations by the school staff, parents’ evenings, participation in school conferences or through written information channels (newsletters, press in the neighbourhood, flyers). The central tasks of the bridge builders are:

- Meeting with the families at agreed locations, determined by the families, to support, inform, advise and accompany them.

- Providing information and advice on educational support services.

- Accompanying them to the appropriate services or specialised agencies.

- Support in understanding forms, letters or information from schools.

- Help with orientation in the neighbourhood, for example, by providing information about services for families with children.

- Support in contacting the school and in exchanging information with teaching and specialist staff.

At the Burgweide school in Hamburg, so-called ‘parental mentors’ (https://www.burgweide.de/eltern-elternberatung.html) support co-operation with parents. Parents were trained to support other parents in challenging situations. On the one hand, this is intended to strengthen co-operation and, on the other hand, to give parents an understanding of school. A school culture has also been developed that considers parents who work here as part of the staff. The ‘parental mentors’ mediate between school actors and parents by creating awareness for each other through their services. They are ‘contact people’ and ‘networkers’ at the same time.

Concrete offers are:

- Organisation of counselling services within the framework of a parents’ café.

- Support with applications and communication (mis)understanding, for example, correspondence with the school.

- Organisation of further education, tailored to the parents’ living environment. These could include language courses, digital learning formats, reading and spelling courses.

- Language translation for important development talks or training courses.

- Representation and networking in the district/social space.

- Support in catching up on qualifications (parenting school).

In Groningen (Netherlands) there is a similar type of bridge building. Whereas in Basel the bridge builders are actors from outside the school, in the Dutch city positions are created by teachers directly in the respective school. There are now 20 positions in a total of 12-13 schools. The so-called ‘brugfunctionaris’ (https://gemeente.groningen.nl/brugfunctionaris) are teachers without current teaching duties with the task of intensifying co-operation with parents. The focus is less on cultural mediation and more on school connection and relationship building between school and parents.

The ‘brugfunctionaris’ are described by the school team as an important resource for building a trusting relationship with parents. An important task is also to make it easier for parents to access the school premises and to talk to them directly on site.

Further support and exchange opportunities

Some schools offer various thematic courses and training for parents. The schools offer a wide variety of topics and focal points, also because they are very much geared to the individual needs of the parents. Exemplary topics are:

- Parent-child courses.

- Language courses.

- First aid courses.

- Life skills.

- Digital learning media.

Some of these courses are designed to help parents better support their children in their learning journeys. Others are designed to empower parents to acquire educational skills themselves. These services are also supported by networking with other actors in the social space. In this way, individual meetings take place with actors from outside the school thus relieving the teachers at school. At the same time, parents have the opportunity to (re)gain trust in the school. Extracurricular partners also make use of such educational offers in order for parents to understand more educational processes.

A frequent form of easy contact is the so-called ‘parental café.’ Parents can meet at these cafés for a certain amount of time. They have some snacks and talk about various uncertainties and questions. This is also an opportunity for the schools to learn more about the needs of parents and the parents can build trust in schools and school stakeholders. This is a way for communication to increase and gain clarification on many topics ranging from information in letters the parents may have received to gaining a greater understanding of the structure of the school system.

Do we actually need ‘collaboration’?

Collaboration should happen necessarily with equal evolvement of each side. Both parents and teachers should be reflective of their predominant opinion of co-operation.

For example, some teachers perceive collaboration with parents as school-based parent involvement. They believe that parent involvement within the school setting should primarily aim to improve students’ learning experiences. It should contribute to students’ success by aligning with the school’s and teachers’ requirements. From this perspective, teachers see the welfare of students as contingent upon the presence of supportive parents and families. Therefore, teachers’ perception of collaboration can be characterised as both children-focused and school-centric.

Educators often perceive the importance of co-operation with parents because they understand that success in school is frequently associated with the socioeconomic capital and resources that parents can provide (Lareau, 2000). This perception leads teachers to hold the view that intergenerational patterns within families are reproductive, as not all parents possess equal ability or resources to offer the necessary support for their children’s success in the school system (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). For instance, parents with higher educational attainment and stable employment may have greater financial resources to invest in educational enrichment activities, such as tutoring or extracurricular programs, which can positively impact their children’s academic outcomes.

In contrast, families facing low educational attainment, negative social modelling, and unemployment often find themselves in an environment characterised by hardship and persistent educational challenges (Lareau, 2000). These challenges can perpetuate a cycle of disadvantage and contribute to a sense of inescapability. Teachers, recognising the influence of these external factors, do not believe that schools, or even themselves individually, can single-handedly reverse such complex and deeply ingrained cycles of inequality (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). This happens because teachers, influenced by the pre-existing subconscious acceptance of social reproduction theories, tend to integrate these beliefs into their practical approaches, resulting in specific causal chains of events that ultimately lead to predetermined outcomes.

Some parents’ theories of action are deeply rooted in their conviction that the school plays a pivotal role in fostering their children’s success. They believe that the school is not only capable, but primarily responsible, for ensuring their children’s academic achievements (Epstein, 2018). This perspective often results in an expectation that the school should take full responsibility for their children’s learning, from providing high-quality instruction to addressing any challenges or obstacles their child may encounter during their educational journey. For example, these parents might expect the school to provide extensive academic support, such as additional tutoring or specialised interventions, if their child faces academic difficulties. They may also look to the school to address non-academic issues, such as behavioural or social challenges, assuming that the school should take the lead in resolving these issues. In this regard, parents’ conceptions and strategies for parent involvement are both child focused and community centric.

As a result, and somewhat ironically, the theories of action held by teachers and parents exhibit a dual nature of simultaneous alignment and near contradiction. They align in their child-centred focus, yet they diverge significantly due to teachers’ school-centric and parents’ community-centric perspectives, which consistently lead to conflicts between them.

These intricate (adverse) exchanges arise due to the divergence in perspectives, conflicting knowledge frameworks, and action theories held by teachers and parents: they have varied interpretations and understandings of the purposes and roles of parental engagement.

School as a social institution serves as the society and has a significant role of creating the school-community partnerships. The concept of a partnership typically implies a collaborative relationship where individuals or groups are perceived to have equal influence and equitable access to resources (Lareau, 2013).

It is recommended that individuals and processes should establish clear provisions when shaping and guiding the framework for mutually beneficial school-family practices. These provisions should consider issues such as recognising and addressing power imbalances and dynamics. Efforts to acknowledge and respect the strengths and perspectives of parents should be implemented without creating a division that devalues school-centred involvement activities that can enhance children’s learning and well-being, and without diminishing the genuine needs of teachers for meaningful support, professional growth, and acknowledgment (Lawson, 2003). In doing so, it is possible to align teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of collaboration, thereby reducing the disparities caused by school-centred parental involvement.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Why is it important to collaborate with parents in inclusive education?

- In your opinion, which barrier is the most significant to teacher-parent collaboration and how can we work with it?

- What opportunities do teachers in schools have to support parents in co-creating and understanding structures and practices?

- What could a non-judgmental culture of dialogue and cooperation with parents in schools look like?

- How the educational inequality could be reproduced during collaboration with parents? How to improve that?

- Why it’s important to develop a consensus of collaboration between parents and teachers?