Section 1: Developing Inclusive Educators

Continuous Professional Development for Staff for Diversity Sensitivity

Fetiye Erbil; Valeria Occelli; and Bodine Romijn

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Imagine that you are a middle school teacher. Alex, a pupil in your middle school, identifies as a young black man with a physical disability. Alex also comes from a low-income family. Alex encounters multiple obstacles as a result of the intersection of his identities. He faces obstacles associated with racial prejudice, ableism, and socioeconomic disparities in the school. You also realise that there is not much support allocated to help students like Alex. You are part of a group of teachers willing to learn more about diversity sensitivity, intersectionality and develop your practices for creating a more inclusive school culture. You also know that there is a group of teachers who avoid talking about these issues and who are reluctant to take part in professional development activities on topics outside their subject areas (e.g., teaching maths or science).”

Throughout the chapter, we will help you examine this case and reflect on what you have read.

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What are the different styles/types of CPD?

- What impact can CPD have on the students, the teachers, and the learning environment?

- How does ethos and culture affect CPD within a school?

- How can you avoid the learning from CPD from moving away from the school when the teacher leaves?

- What is the importance of CPD within the school environment?

Introduction to Topic

In many European countries diversity is increasing, creating super-diverse classrooms. Super-diversity (Vertovec, 2007, 2010) refers to the fact that diversity is a far too complex concept to be defined by single characteristics/differences, such as gender, learning abilities or cultural background. These characteristics interact with one another, creating rich personalities and unique experiences of people. Unfortunately, not all experiences are equally positive. Numerous studies show that diversity characteristics are related to disadvantages and inequalities. Looking at the school context, we for instance see that there are unequal (learning) opportunities for girls, children with disabilities, children with darker skin tones, children from cultural or religious minorities, and so on. Because the identity of children consists of an interplay of diversity characteristics, this also means that some children experience disadvantages and inequalities at more than one level (for instance when you are a black girl with a learning disability). This is called intersectionality (Bešić, 2020).

Let’s pause and reflect

Think about your student, Alex.

- How do his different identities intersect?

- How does this intersectionality result in more disadvantages for him at school?

- Think about the other students in the school. What might be similar cases?

Inclusive education is meant to tackle all students’ diversities (and their interplay) in order to reduce all forms of exclusion, marginalisation and inequalities and to guarantee quality education for all (see Goal 4 of the UN 2030 Agenda; UNESCO, 2015). To fulfil this role, schools should be a place where all students are equally supported in their well-being and development. This means we should unequally invest in students, because of their different experiences. Students should receive the best possible support adapted to their needs (equity), rather than giving every student the same treatment (equality). In order to achieve this, we need teachers who are sensitive to the diversity of the class. Diversity sensitivity is about the ability to acknowledge, accept and value diversity. These are important steps in creating an inclusive environment that supports students’ well-being (Pastori et al., 2019, 2020).

Many teachers indicate that they lack this diversity sensitivity and that they feel ill-prepared for teaching the super-diverse classroom (e.g., Banjeree & Luckner, 2014; Slot & Nata, 2019). This chapter describes how continuous professional development can be used to further support teachers in working in diverse classrooms.

Continuous Professional Development

Professional development refers to all the actions and activities focused on education, training and development opportunities for teachers with the ultimate goal of improving students’ developmental or educational outcomes (Sheridan et al., 2009). In other words, professional development is not about becoming a better teacher, but about becoming a better teacher for your students. Continuous professional development (CPD) emphasises that this learning should be a continuous and ongoing process. Teachers are learners themselves, and their initial teacher training is just a first step in the process, but they continue to develop as teachers long after that. With respect to diversity sensitivity, we should be aware that our understanding of “diversity” is evolving over time too, making it necessary to continuously develop on the topic.

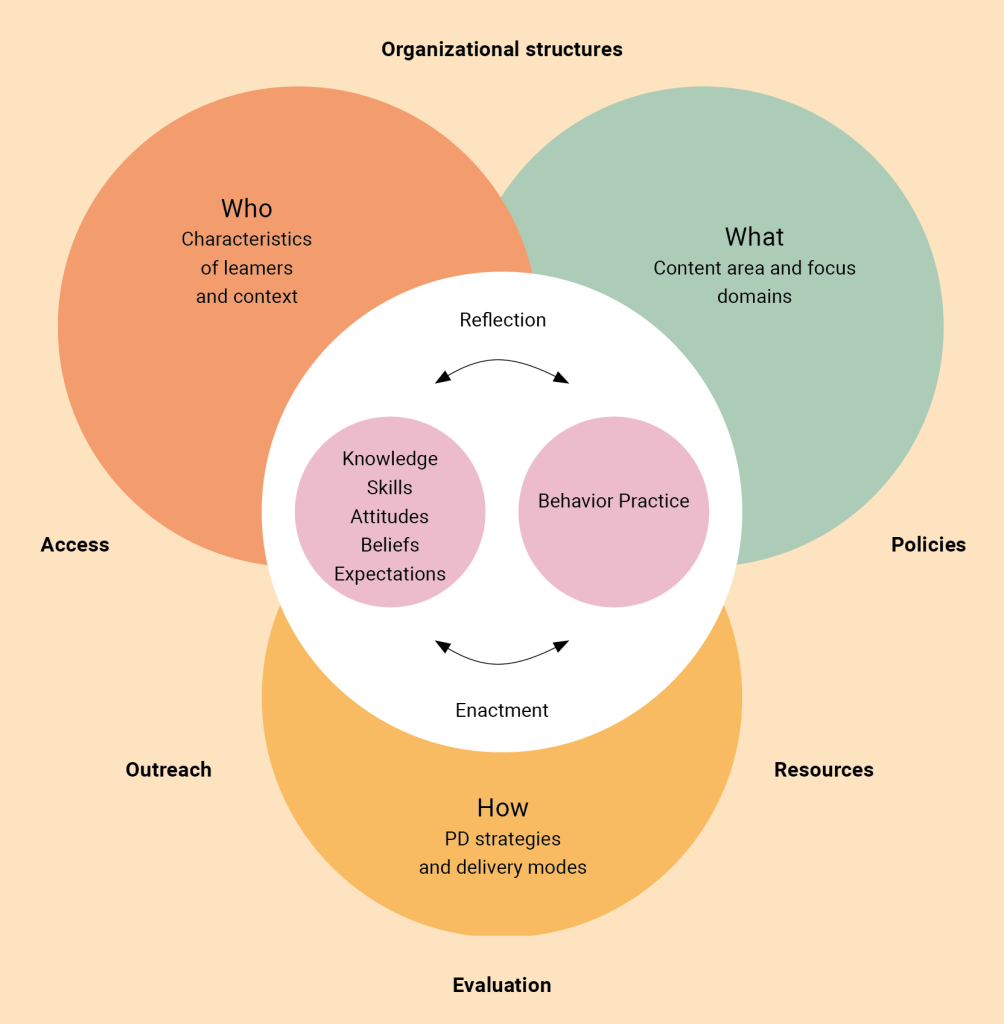

CPD can take on a lot of different forms, ranging from short workshops to extensive multi-year curricula. However, not all forms of CPD are equally effective (Civitillo et al., 2018; Parkhouse et al., 2019). CPD is most likely to be effective and sustainable if it follows an embedded and contextual approach (Romijn et al., 2021). Using the following model (see Figure 1), we will explain what this means.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of professional development

Based on Slot et al., 2017 as presented in Romijn et al., 2021

Key components of CPD

When choosing or designing a CPD activity, it is important to think about its key characteristics: who is it for, what is it about, and how is it delivered (Buysse et al., 2009).

Who. CPD is always for someone, so we should consider the characteristics of the learners and their context. For instance, a teacher who has a lot of experience with students with visual impairments, might need a different approach from a teacher who has never worked with such students before. A teacher with a minority background can make use of other strategies when trying to bond with students with a minority background, than a teacher with a majority background can. A teacher who is resistant to change will probably need a different strategy than a teacher who has an internal motivation to make a change because they want to solve a certain problem in their classroom. Thus, CPD is most likely to be effective when it is adapted to who the learner is.

What. CPD is always about a certain topic or targets a specific domain such as knowledge, skills, beliefs or behaviour. Depending on what your focus is, different strategies might be useful. For instance, if there is a need to learn new knowledge, reading a book (like you are doing now) can be a useful strategy. However, if teachers wish to improve their skills in communicating with children from different backgrounds, merely reading a book will not necessarily work. Thus, an important step in choosing or designing an effective CPD activity is to properly define what needs to be learned (learning goals).

How. A wide range of strategies and delivery modes exist, such as workshops, immersion experience (i.e., doing an internship), coaching, video-feedback, critical friendships, learning communities, online self-ratings. When learning goals are more complex, a combination of strategies and delivery modes is recommended. In general, research shows that strategies that are more intensive (in duration and dose) and have a collaborative component are more likely to be effective (Siraj et al., 2019). Later in this chapter, we will elaborate on what strategies and delivery modes are most common and how they can be effectively used.

Individual teachers in a wider context

Figure 1 also shows that while development happens within an individual teacher (intra-individual level), this individual teacher is always part of a wider context. To understand how development occurs, we must first investigate the underlying mechanisms within the individual. Teachers all have their own unique set of characteristics, related to their personal background and beliefs, previous experiences, knowledge and skills. This informs how they behave in classrooms and what practices they are likely to use with their students. However, this relationship between what one knows, feels or believes on the one hand and what one actually does on the other hand is not as straightforward as one might believe. Studies for instance show that teachers’ explicit attitudes towards diversity are not always in line with their implicit beliefs and actual behaviour (Álvarez Valdivia & González Montoto, 2018). By using the mechanisms of reflectionand enactment teachers can develop their knowledge, skills and beliefs as well as their behaviour and practice. In the next section we will elaborate on these internal mechanisms.

Though CPD is a process that primarily happens within the individual teacher, we cannot think of the teacher as a sole entity that is completely separated from their context. Teachers are always part of a classroom, part of a team of teachers and support staff and part of a school within a local community. Moreover, CPD has the ultimate goal to impact the students’ well-being and development. Therefore, it is necessary that CPD also has a sustainable impact that moves beyond the individual teacher. In the last part of this chapter, we will further discuss what needs to be done to make CPD more sustainable by properly embedding it within the wider context.

Let’s pause and reflect

Read this sentence one more time: “Teachers all have their own unique set of characteristics, related to their personal background and beliefs, previous experiences, knowledge and skills”.

- Think about your colleagues in your school. What do you know about their personal background?

- What do you know about their beliefs, previous experience, knowledge and skills about working with a diverse group of learners?

- With your group, what can you do to learn about the needs of all teachers so that you can have a starting point to build on in your professional development attempt?

Key aspects

Individual processes in learning and development

At the core, learning and development is an individual process. When engaging in CPD, teachers contribute a unique combination of characteristics encompassing their cultural background, upbringing, personal experiences, beliefs, as well as their existing knowledge, skills and competences. These individual variations impact how teachers approach their role as learners during CPD, their motivation and engagement, and the process outcomes. In this section, we will discuss the importance of individual belief systems for developing diversity sensitivity and elaborate on the mechanisms of reflection and enactment.

Teachers’ belief systems

All teachers have a belief system, which is a set of developed assumptions, beliefs, attitudes and values (Spies et al., 2017). Though these terms are related, they cannot be used interchangeably, and a relevant distinction can be made especially between beliefs and attitudes. Teachers’ ideas, beliefs and values encompassing the different factors involved in education, have been referred to as teachers’ beliefs (Pajares, 1992). When beliefs towards a specific object, for example, diversity inclusive education, are organised and predisposed to action, this cluster of beliefs becomes an attitude (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993).

The main components of attitude are cognitive, affective, and behavioural, indicating that attitudes concern the individual’s knowledge, feelings, and predispositions to (re)act toward a specific object (de Boer et al., 2011). When considered in relation to diversity in education, the cognitive component refers, for instance, to the teacher’s beliefs regarding the adequacy of their school to embrace diversity (for example, “I hold the belief that students with special needs should be included in mainstream schools”), the affective component to teacher’s emotions (for example, “I am worried that students with behavioural issues may disrupt the classroom environment”), whereas the behavioural component pertains to how the teacher is inclined to behave in relation to a specific scenario (for example, “I can offer afternoon activities to support non-native speaking students”). According to the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 2001), teachers’ attitudes play a role in determining their actual behaviour, insofar as attitudes are one of the factors influencing the intentions to perform it (for example, positive attitudes are likely to result in more open and welcoming behaviours, while negative attitudes are more likely to lead to avoiding and/or rejecting behaviours; see the box below for examples related to Alex’s case). Attitudes towards diversity inclusive education have been found to be influenced by a wide range of factors (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002), including years of teaching experience and higher perceived self-efficacy, which you will learn more about in Section 2.5 (Kunz et al., 2021).

Let’s pause and reflect

Think about Alex’s case and possible teacher reactions in your school. Do they reflect the cognitive, the affective, or the behavioural component of attitudes?

“I believe that students with disabilities can be better supported in other schools”

“I’m afraid students coming from low SES backgrounds can disturb the order and change our pace because they tend to be slow learners”

“I’m not sure if I have enough time to learn about the case of every student. They are all different. I don’t have enough resources to support all of them so I can’t do anything”.

Another distinction worth mentioning here is between explicit and implicit attitudes. Explicit attitudes are conscious and generally overtly reported. However, especially in relation to sensitive issues, such as diversity inclusive education, people might have opinions diverging from mainstream social norms. In this case, individuals might be more reluctant to overtly express what they think. For instance, a teacher might think “Dealing with diversity is so stressful that I would prefer to work in a special educational provision system rather than in an inclusive one,” but might feel that this would not be well received by colleagues and supervisors. In contrast, implicit attitudes are automatic reactions to an object, which can be observed even in absence of the individual’s awareness (Glock et al., 2019). We will see in Section 2.4 an example of how implicit attitudes affect teachers’ practice.

The individuals’ existing attitudes can influence the way they perceive and interpret new information. Indeed, to simplify information and make rapid decisions, individuals often activate cognitive patterns that align with their pre-existing beliefs and attitudes. These systematic patterns of thinking are known as biases (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Although biases allow people to handle the high amount and complexity of information in a time and resource efficient way, they can nevertheless lead to oversimplification and generalisation and thus open the doors to stereotypes and prejudices (Haselton et al., 2005).

Teachers, just as everybody else, may apply their generalised knowledge or stereotypical beliefs to their students, often without being fully aware of that (Glock et al., 2019; Turetsky et al., 2021). Examples include the assumption that students in culturally diverse schools are more prone to disruptive behaviours, that students with low socioeconomic background are less likely to be high achievers, that girls are more likely to excel in verbal tasks and boys in STEM subjects, or that all students have a canonical family. Teachers’ misconceptions about their students can significantly influence their interaction with them, the assessments and evaluations, as well as achievement expectations. Research shows that teachers’ biases have a profound impact on students’ actual learning outcomes and can contribute to the perpetuation of educational disparities (Pit-ten & Glock, 2019). However, while teachers’ attitudes towards diversity typically have a lasting impact on their behaviour, it is crucial to recognise that these attitudes can nevertheless be modified through targeted CPD activities (Kunz et al., 2021).

Let’s pause and reflect

Think about your school again and think about the different teachers who are teaching Alex.

- Do you think he has the same experience with every teacher?

- What are the different attitudes among teachers towards inclusive practices in your school?

- How do these attitudes differ and based on what?

- What might be the ways to understand the reasons for different attitudes so that you can start working on developing more inclusive and diversity sensitive practices?

The relation between belief systems and CPD engagement

Teachers’ beliefs towards diversity influence their motivation to take part and commit to CPD initiatives (Liu et al., 2019). Additionally, any CPD approach, by employing specific practices, establishes particular ways of knowing as more significant than others (Musanti & Pence, 2010). Hence, it is unsurprising to witness resistance among teachers when it comes to engaging in CPD initiatives (Musanti & Pence, 2010). The sources of resistance are usually classified as individual resistance and political resistance (Musanti & Pence, 2010). Individual resistance reflects the conflict stemming from a discrepancy between the expectations or requirements placed on the teachers and how those align with the teachers’ needs and evaluations. For example, teachers may perceive ad-hoc training on certain topics as relevant to only a subset of the category, leading them to implicitly question its relevance (for example “It is not my thing”, “Why should I be involved? This doesn’t apply to me”). Political resistance instead refers to the resilient act of reclaiming a sense of agency (“I didn’t choose this, what isn’t my voice heard when it comes to planning and designing such initiatives?”).

Let’s pause and reflect

What you can do in the professional development initiative that you start with fellow teachers in your community is:

- Gain an understanding of the existing stereotypes, prejudices and misconceptions teachers might have towards intersecting identities students?

- Create a safe and supportive space for all teachers to talk about what they know and what they want to know?

- Devise a plan on how you want to empower your school community in becoming more knowledgeable and skillful toward diversity sensitive practices?

Teachers’ questioning implicitly challenges the perceived necessity of such training, which, in addition to pre-existing attitudes toward diversity inclusive education, might undermine the initiative as a whole. Resistance can nonetheless offer an opportunity of reflection on the scopes and aims of CPD initiatives (Walter et al., 2023). Even individuals who are “on board” may still have questions or concerns about CPD initiatives (for example, “Do I have the necessary skills to embark on this?”, “What am I going to be exposed to?” “What am I supposed to learn?”). Some good practices help to promote resisting teachers’ compliance with the proposed activities. For instance, establishing a psychologically safe environment, where group members feel safe to share and contribute, without any fear of being judged, is of crucial importance (Edmonson & Lei, 2014).

Let’s pause and reflect

Your teacher learning community is working slowly but steadily. You have started getting together regularly with other teachers, organising meetings, doing readings and inviting experts. Not all of these events are initiated or followed by all the teachers in the school but most of the teachers care to join in at least a few of them and contribute to the community. However, you observe that there is a group of teachers who are hesitant, sometimes critical/judgemental of what you do.

- Why do you think they demonstrate resistance?

- What are their reasons for not joining?

- What can you do to create a channel for dialogue and communication to understand each other?

- What can you do to make them wonder about your community’s activities?

Transformative learning

Given the sensitive nature of the topics involved, it is highly recommended to adopt a comprehensive approach when designing and delivering CPD activities aimed at fostering diversity within the educational environment. Two methods have been demonstrated to robustly mediate professional practice improvement (Cole et al., 2022):

- Critical reflection: refers to the practice of applying critical thinking to personal experiences, while at the same time taking some distance from them. When teachers engage in critical reflection, they ask themselves questions to extract meaning from the experienced events (Cole et al., 2022).

- Reflective practice: it arises from the recognition of a disparity between a new experience and the existing beliefs and knowledge one holds. This awareness prompts teachers to reframe their implicit assumptions about practice, in search of a new and more promising course of action, eventually bridging the gap between theory and practice (Russell, 2018).

How are critical reflection and reflective practices implemented in CPD? How can CPD make the best use of them? According to some authors, the learning potentials of critical reflection and reflective practices in CPD can be fully realised within a transformative learning experience framework. This framework promotes a profound structural shift in thinking, as opposed to a superficial additive learning approach, where most existing beliefs remain unchanged (Wall, 2018). What does this mean in practical terms? This will be addressed in the following section.

Cognitive dissonance as a trigger of behavioural change

When considering the cases of two of Alex’s teachers; one, in an attempt to compliment him, might exclaim “If someone had made me guess where you live, I wouldn’t have bet on that neighbourhood!” Another one tends to constantly monitor him with the corner of her eye while in class. Both teachers might perceive themselves as treating Alex and the other students equally. However, with their behaviours, they are acting on their implicit attitudes, covertly denying or misvaluing Alex’s background, or implicitly making assumptions about his trustworthiness and compliance to the norms. Behaviours like these qualify as microaggressions, acts that subtly communicate disrespect, degradation, and/or hostility that are directed against people in marginalised groups, either intentionally or unintentionally (Lilienfeld, 2017; Steketee et al., 2021). If questioned about their action, these teachers might say that they are genuinely complimenting him or devoting the same amount of attention to all pupils. This might nevertheless induce a conflict, a cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957), between their overt egalitarian attitudes and covert biassed intentions.

According to cognitive dissonance theory, the inconsistency between what people know or think and new pieces of information makes them experience a state of psychological tension. In the attempt at alleviating the emerging psychological discomfort, they aim to make their beliefs and new information align, by either modifying their existing beliefs or by assimilating the new information, so that the discrepancy can be reduced (McFalls & Cobb-Roberts, 2001). Remember we mentioned the concept of a transformative learning experience process early on? CPD activities that foster a sense of cognitive dissonance in the teachers, just like the one experienced by Alex’s teachers, facilitate transformative learning (Thompson & Zeuli, 1999). To make the transformative learning experience more likely to be effective, other elements should be incorporated:

- Creating a structured environment that allows teachers enough time, the appropriate contexts and support, to allow teachers to reflect on and reconcile the conflict they experience.

- Incorporating activities that both stimulate and resolve this cognitive dissonance directly within teachers’ daily teaching situations and practices, ensuring they are not isolated from their classroom work.

- Empowering teachers to cultivate a fresh set of teaching approaches that align with their newly acquired understanding. This will enable them to effectively implement their newfound knowledge in the classroom, thus developing a repertoire of practices that are in harmony with their revised perspectives.

- Engaging and supporting teachers in an ongoing, continuous cycle of improvement and growth, providing them with the necessary guidance.

When we refer back to Alex’s teachers’ example, becoming aware of the biases being held and that some behaviours can be perceived as microaggressions act as the starting point to enable a progressive behavioural change. This, in turn, stimulates Alex’s teachers to monitor their behaviour, so that potential microaggressive acts can be detected before being enacted, and thus be progressively avoided. In more general terms, practices that are implemented within the educational settings feedback and become a matter of further reflection and, in turn, nourish further reflection, so that they are constantly improved and made more effective. Through this circular process, teachers become more responsible to their own learning, and more accountable as professionals (Walter et al., 2023; Yost, 2006), and eventually develop a higher perceived self-efficacy, a concept you will learn more about in the following section.

Teachers’ self-efficacy

The term “teachers’ self-efficacy” defines the complex set of beliefs teachers have about their capabilities to effectively handle the tasks, obligations, and challenges related to their profession (Lazarides & Warner, 2020). According to Tschannen-Moran and collaborators (1998), two cognitive processes contribute to the emergence and development of teachers’ self-efficacy. The first process involves examining the task and its context, identifying the challenges of teaching and weighing them against the resources at hand. The second process involves evaluating one’s own skills and acknowledging any areas where they fall short in relation to the task. Different sources of information contribute to these processes (Bandura, 1977):

- Mastery experiences: outcomes of direct personal action (for example, successes enforce self-efficacy, failures weaken it).

- Vicarious experiences: observation of others and comparison with one’s own experience. Useful when novel and challenging situations are faced, where personal accomplishments are still lacking or not yet mastered.

- Verbal persuasion: performance feedback from a supervisor or a colleague.

- Somatic/affective states: emotional or physiological reactions.

Interestingly, there is a reciprocal relationship between the information sources of self-efficacy, their interpretation by the individual, and the resulting self-efficacy itself (Bandura, 1977). This means that, if teachers believe that their performance is being successful, this belief will likely result in the enhancement of their self-efficacy perception and, in turn, contribute to their expectation of future success, thus establishing a sort of virtuous self-fulfilling prophecy (Ulbricht et al., 2022). The cyclical nature of teachers’ self-efficacy implies that, whenever a task is successfully completed, the positive outcome contributes to reinforce one’s self-efficacy beliefs and, in turn, good practice (Gutentag et al., 2018; Saglam et al., 2023). CPD can play a vital role in addressing the challenges of diversity while simultaneously enhancing teachers’ self-efficacy. By improving teachers’ self-beliefs and confidence, significant progress can be made in effectively managing diverse classrooms and overcoming the associated challenges (Lazarides & Warner, 2020). The methods used to achieve this goal will be the topic of the next section.

Useful Strategies for Effective CPD for Diversity Sensitivity for Teachers

Teaching requires continuous learning and adaptation to new methodologies, concepts, and topics (Desimone, 2009; Kyndt et al., 2016). To adapt to societal and educational changes toward diversity, instructors must increase their knowledge, question their beliefs, develop their skills, and reflect on their instructional practices (Brookfield, 2002). This necessitates the creation of professional learning environments for instructors that incorporate reflection, interaction, and collaboration as essential CPD strategies. These methods – the “How” and “What” components of the model presented in Section 1.1 – will be described in detail within this section.

The Role of Reflection

Reflection is a metacognitive action that helps us to think about our thinking, beliefs, or behaviours. It allows us to be critically aware of what we do, how we do, and this self-realisation allows us to understand the influence of our thinking and beliefs on our actions (Dewey, 1933; Habermas, 1971; Lempert-Shepell, 1995). Reflection is a valuable tool for teacher professional development, particularly when it comes to cultivating sensitivity to diversity among educators. Therefore, a reflective approach needs to be the key element of all teacher-learning environments (Postholm, 2008).

Through self-reflection, teachers can evaluate their own biases, prejudices, assumptions, and deeply rooted beliefs about differences. They can consider how their own cultural backgrounds and personal experiences shape their perceptions of and interactions with students from diverse backgrounds (Fiedler et al., 2008). CPD activities to foster diversity sensitivity need to present opportunities for teachers in which they can be reflective on their instructional practices, the type of classroom and school culture they cultivate, and the level of inclusive practices they embrace (Gay, 2010; Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017). Through the medium of self-reflective practices, teachers can be more aware of how their actions influence their students, which can open space for further discussion and room for improvement of more inclusive practices (Acquah et al., 2016; Ragoonaden et al., 2015).

Teachers can establish inclusive and supportive learning environments that celebrate and embrace diversity through the ongoing professional development of these knowledge, skills, and competencies. They can effectively meet the diverse requirements of children, promote social justice, and promote effective learning for all students (Gay, 2013; Leeman & Ledoux, 2003). It is important to note here that being self-reflective is a skill that needs to be practiced and refined over time. Reflecting on your knowledge and practices is an ongoing, cyclical process which requires practice, time and dedication. Also, it is not enough to be self-reflective. In professional development activities, teachers need to co-reflect with their colleagues on their teaching practices and challenges they have to address diversity issues in their school community.

Practical Suggestions:

At this point, it might be useful to provide some concrete examples of reflective questions teachers can make use of in CPD. If teachers want to be critical of their professional practices, they might consider asking such questions:

- Am I aware of the different backgrounds of my students? What do I do to learn more about it?

- Am I aware of my own biases and how they influence my students?

- Am I creating an inclusive classroom environment in which my students feel valued and respected?

As well as these questions, continuous professional development programs can use methods such as reflective journaling, structured reflection exercises, peer analysis of classroom scenarios on inclusivity, and feedback from peers (Arrastia et al., 2014). The incorporation of feedback and evaluation processes into professional development activities enables teachers to receive input from peers, administrators, and outside experts. These feedback mechanisms can focus specifically on diversity sensitivity, providing teachers with constructive feedback on their practices, identifying areas for development, and providing suggestions for enhancing their approach to diversity in the classroom. Teachers are motivated to refine their strategies and implement more inclusive practices as a result of the feedback and evaluation they receive, gaining an outside perspective and evaluation from other teachers.

Let’s pause and reflect

With your teacher learning community, you have read and learned about the importance of being self-reflective and also reflecting with your fellow colleagues. In your learning journey toward creating a more inclusive school environment:

- What kind of reflective questions can you ask?

- What kind of teaching practices do you think you should reflect on together?

- Can you reflect on any assumptions or biases that could affect your perception and interactions with the students of the community. How would you combat these biases and ensure that all students are treated fairly?

The Role of Interaction

As learners of all ages and backgrounds, teachers are also social learners (Wardford, 2011). They learn and develop through interacting with their fellow teachers, exchanging ideas, engaging in valuable discussions, and listening to different perspectives within their teacher community (Kyndt et al., 2016). Therefore, integrating elements of interaction in all forms of teacher professional development matters for their effective learning (Postholm, 2012).

Interaction plays an essential role in CPD for teachers in becoming more diversity sensitive. Interaction provides teachers with opportunities to engage with diverse backgrounds, allowing them to deepen their understanding of diversity, the intersectionality of differences, and ways to make classrooms more inclusive and safer learning environments for their students. Interaction enables instructors to engage in experiential learning in which they actively participate in discussions and simulations that promote understanding and empathy for diverse perspectives. By interacting with individuals from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and identities, instructors can acquire first-hand experiences and insights that heighten their sensitivity to diversity. This could be done by first learning about the teacher community’s diversity (Postholm, 2012).

Practical Suggestions:

In CPD, to promote diversity sensitivity, interaction can be used as a tool to encourage open dialogue and reflection among teachers. Teachers can challenge stereotypes and broaden their perspectives about the complexities through meaningful dialogues and discussions that they engage in with their colleagues.

Interaction can also be used as a way of engaging with diverse communities, including students, families, and larger communities. This can be done by inviting speakers from various backgrounds, organising cultural activities, participating in community initiatives, or forming partnerships with local organisations working on the intersection of diversity.

Let’s pause and reflect

You, as a group of teachers, came together to learn more about Alex’s case and to empower yourself to address all students in your school community. Most of the focus of your discussions was about diversity among your students. However, have you looked at the diversity within the teacher learning community you have formed? You can ask these questions in your meetings to deepen your understanding of each other and then you can talk about what you think of the group’s answers:

- How aware am I of the diversity of our teacher-learning community? Do I comprehend the unique experiences, origins, and points of view of my fellow educators?

- Have I taken the time to learn about my colleagues’ cultural, linguistic, and social identities? What have I learned? What didn’t I know?

- Are our teacher-learning community discussions and activities inclusive and available to all members of the teaching staff?

- In our conversations, do we actively search out and value diverse perspectives?

- Are there opportunities for instructors of varying backgrounds to share their knowledge and experiences?

The Role of Collaboration

In contrast to interaction, where teachers primarily engage in communication and learning from one another, collaboration in CPD involves actively working together, making joint decisions, engaging in collaborative tasks, and fostering communities of learners (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). Collaborative professional development allows teachers to learn from their colleagues and share their knowledge and expertise in the areas they feel competent (Garet et al., 2001). Teachers can contribute to a collective body of knowledge by exchanging ideas, strategies, and resources through collaborative interactions (Levine & Marcus, 2010). Teachers can observe and learn from one another’s instructional practices and approaches to creating a supportive and inclusive school climate when they collaborate. Peer support and feedback can help teachers in gaining new perspectives, refine their abilities, and overcome obstacles more effectively (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Collaboration also fosters the development of teacher-professional learning communities and networks within educational settings.

Collaborating becomes much more important when it comes to designing CPD on diversity sensitivity and inclusivity. It is an important element of teacher learning of diversity sensitivity because it offers opportunities for teachers to learn about the diversity within their groups, to work on cases and scenarios, and to find solutions for common problems based on classroom practices on diversity and inclusivity (Szelei et al., 2020). Collaborative learning brings together teachers with diverse experiences, backgrounds, and expertise. This diversity enriches the learning environment by providing a variety of perspectives, encouraging critical thought, and nurturing a broader understanding of complex and challenging issues (Pijl, 2010).

Practical Suggestions:

In CPD programs, collaborative interactions can take the form of group discussions, case studies, workshops, and joint reflective exercises, giving teachers the opportunity to learn from one another and increase their collective understanding of diversity and inclusivity. Regardless of their experience, teachers can form or join the existing professional learning communities within and outside their school community in which they can collaborate on broader projects, develop materials, resources and increase their understanding of diversity-sensitive educational practices.

Case studies and simulations can also be tools to work with as they provide teachers with realistic and classroom-based scenarios in which they must apply their knowledge of diversity sensitivity. By engaging in group discussions and problem-solving activities based on these cases, teachers can analyse the complexities of diverse student needs and develop strategies for creating inclusive and equitable learning environments for everyone.

Let’s pause and reflect

Working together with colleagues may not be as easy as it seems, especially when it comes to sensitive or challenging issues like diversity sensitivity. Here are some questions you can use to reflect on the collaborative practices of your teacher group:

- How well am I able to communicate and work efficiently with other teachers who come from a variety of backgrounds?

- How can we make our collaborative efforts to enhance diversity awareness in an environment that encourages sharing of ideas and information?

- How can we learn best from the perspectives of other teachers?

- How can we support one another in addressing biases and creating learning opportunities for all students that are equitable?

Delivery Modes

CPD programs vary in their forms depending on the available resources, the needs of the learners, the context, and the learning culture in the schools. Based on their needs and available options, teachers may enrol in one or more formats to continue their learning and development on any subject including diversity sensitivity and inclusive educational practices. These modes of delivery can be listed under four main categories: short training programs, mentoring, team-based learning, and professional learning communities (PLC).

Short training programs. Short training programs include formats like seminars, webinars, one-shot presentations, and courses (Waitoller & Artiles, 2013). The content is designed and prepared by experts for the teachers. They are the most common forms of professional development activities for teachers as they are practical and easily organised. They provide structured and focused learning opportunities for CPD on diversity. They are ideal for introducing new ideas, concepts, or topics on diversity sensitivity. However, they are mostly short in duration and there is not much room for interaction and collaboration among teachers in such formats (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

→ Mentoring. Another mode of delivery is mentoring, in which teachers work with more experienced colleagues or academics from the field (Hudson, 2013; Kennedy, 2005). Through mentoring, experienced educators provide individualised support and feedback to less experienced teachers to improve their practices (Anderson & Shannon, 1988). Teachers have opportunities to make individual plans, practice what they learn, and reflect on it with their mentors. It allows critical thinking and reflecting on the knowledge, beliefs, attitude and practices of the teachers on diversity sensitivity and inclusive practices (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Santoro & Forghani-Arani, 2015).

Team-based learning. In team-based learning, some teachers from the same school work in small teams on new concepts, skills, and practices (Coolahan, 2002). These are usually organised by the professional development units of the schools and experts present the newly introduced content. Team-based learning makes use of collaborative learning experiences, by encouraging active participation, self- and co-reflection, and cooperation of teachers (Thompson & McKelvy, 2007).

Professional Learning Communities. Lastly, Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) are collaborative structures that are designed for and by teachers of the school community (Keung, 2009). They are often built around a real need or a challenge that teachers have been experiencing; therefore, allowing them to get together, devise a plan to meet their own needs, and collaborate on reaching and sharing knowledge (Hord, 2009). Through PLCs, teachers take collective responsibility for their own learning along with their colleagues’ learning, work on problems they bring from practice, and take on new approaches to transform themselves and the classroom culture they create for their students (Antinluoma et al., 2021; Ohi et al., 2019). PLCs can be formed by teachers within and outside the school community, making use of available resources, and inviting experts and other teachers who are willing to work on the same topic (Opfer & Pedder, 2011). As they are initiated by teachers and allow space for the agency, contribution, and needs of the participating teachers, PLCs represent a sustainable model for CPD (Borko, 2004; King & Newmann, 2000). We will deal more specifically with CPD sustainability in the next section.

Let’s pause and reflect

The formats and design of teacher professional development activities change and the effectiveness of these depends on your needs and expectations, in addition to how well the CPD activities are designed and delivered. Based on the needs and expectations of your teacher group:

- How can you learn about the available CPD activities that you might be interested in?

- What are the existing communities and networks you can reach out and join to learn more about diversity sensitive practices?

- How can you contribute to the development of a learning community among the teachers in your school?

- Which forms of delivery may serve the needs of your contexts the best at the given moment?

How can we make continuous professional development sustainable?

Research shows that many CPD activities have a positive impact on teachers (Bottiani et al., 2018; Parkhouse et al., 2019). However, effectiveness is usually measured using self-reported data of teachers. In other words, asking teachers if they feel like they developed in a positive way after a CPD activity (Romijn et al., 2021). Though it is great that teachers feel CPD has an impact, it is also necessary to measure this impact with more objective measures, such as classroom observations or student development measures (like test scores). Ultimately, we want CPD to change teachers’ behaviour and practices to have an impact on students’ development and well-being. As discussed earlier, the relationship between what teachers think or feel and what they actually do is not that straightforward. Therefore, just investigating if teachers think they changed is not enough.

Unfortunately, regarding the topic of diversity sensitivity, there is less research on what CPD activities have a positive impact on students’ development and what activities are effective in the long run (Romijn et al., 2021). However, the consensus seems to be that short training, which has a rather individual and passive character, is not the most effective form for sustainable change. The impact of this training is likely to be very limited (one teacher, one classroom) and often fades over time, with teachers going back to their old habits. What is even worse, is that teachers and schools seem to invest most of their time and resources in short training CPD (Lumpe, 2007). Therefore, the school system needs a shift towards more sustainable forms of CPD. To achieve this sustainable change, we should ensure that CPD is embeddedwithin the wider context.

Embedded continuous professional development

Embedded means that CPD should not stand on its own in terms of time, people and context. If CPD is properly embedded, the impact is generally bigger and less likely to fade over time.

Time. CPD activities that have a higher intensity are more likely to be effective. The impact of a single workshop in one afternoon generally has a smaller impact than a multi-week training program. Thus, teachers should preferably engage in CPD activities that ask for a bigger time investment or should search for opportunities to intensify short CPD activities. For instance, after following a single workshop, one could schedule monthly moments to take the time to discuss the content of the workshops with colleagues, to reflect on how well newly implemented practices work, or to refresh the acquired knowledge.

People. CPD activities that target individual teachers, or the individual learning process are less likely to yield a big impact. Individual CPD can take many forms, from reading a book by yourself to reflecting on a video of your practice. Even if CPD is facilitated in groups, for instance when you complete training with fellow professionals from other schools, the focus of the activity is often still on the development of the individual teacher. Individual CPD activities can be very effective, especially when they are intensive and well-adjusted to the teachers’ context (like coaching-on-the-job). However, a change in one teacher will only affect a small group of students within the school. Once that teacher leaves their position at that particular school, the impact on these students is lost. Therefore, it is important that CPD activities are team-based. In other words, multiple members of the same school team should be engaged. These could be other teachers but also support staff. By sharing knowledge and good practices within a team, the impact of the CPD is likely to be more sustainable.

Context. There is no such thing as the perfect ‘one size fits all’ CPD activity. That is because the context in which teachers work are very different. If one training was very effective for one teacher, this does not mean that the exact same training will work equally well for another teacher. Properly embedded CPD considers who the teachers are, what their context looks like, and how the CPD outcome can be implemented in their classroom.

This calls for a needs assessment. Several studies show that when there is a mismatch between the CPD activity and what the teachers within their context need, CPD is more likely to fail (Spies et al., 2017). A needs assessment can take on several forms. Teachers could formulate their own learning goals or write down what problems they encounter. Also, other stakeholders in the school, like support staff, students or parents can provide useful information on what CPD is needed in the school. Besides such subjective measures of needs, information could also be gathered by more objective standards. For instance, by using observation tools or questionnaires to measure teachers’ diversity sensitivity, self-efficacy, or prejudice.

Let’s pause and reflect

Suppose that you have decided to engage in a long-term CPD process with all the teachers in your school community.

- What can you do to conduct a needs assessment before your CPD?

- How can you understand the needs of your context?

- How can you learn about the expectations, goals and preferences of your teacher learning community?

Important conditions to create embeddedness

Creating embedded CPD in schools is easier said than done. Only if the conditions are right, teachers can engage in embedded CPD. This comes down to four important considerations: the school’s resources, structure, culture and policies.

School resources. Teachers need sufficient resources to develop their school resources. The most important resource they need is time. In many countries, the school system is under pressure leaving teachers little time to engage in CPD activities. Teachers need time inside and outside of the classroom. CPD is not well embedded if the school cannot facilitate teachers with sufficient hours to learn new knowledge, prepare activities, discuss practices and perspectives with colleagues, observe each other, and reflect on your development. CPD is not properly embedded if the school curriculum is so full that it leaves teachers with no room to try out new training within the classroom.

Besides time, other important resources are materials and external expertise. Imagine a teacher who wishes to improve their skills in supporting neurodivergent learners. On a teacher forum they read about these special Pictionary boards that can help teachers to better communicate with their students. If the school cannot provide the necessary materials for this, the teacher is hindered in their professional development (Biasutti et al., 2019). The use of external expertise has a similar story. We cannot expect teachers to be knowledgeable and skilled for every form of diversity as soon as they finish their initial teacher training. To support their development, they might need external expertise. If the school does not have funds to hire expert coaches or to send teachers to specific training programs, CPD stagnates.

Let’s pause and reflect

After you have completed the needs assessment for the CPD for your community, it is time to look at the other factors that will affect the progress of your learning journey such as:

- What are the available resources that your school provides to sustain your CPD?

- How much time are teachers willing to allocate for the CPD activities?

- What can you do if the available resources are not enough, and you need more support?

School structure. As discussed earlier, CPD is preferably team-based on a regular basis. This is easier to achieve when there are structures within the school context that support regular evaluation, communication and collaboration within the team. Useful structures are for instance school wide study days in which the whole team takes the time to evaluate the schools’ performance and to decide on shared development goals. Another example is to assign buddies that can observe and feedback each other every now and then or to create smaller sub teams within the school that can meet up on a regular basis to reflect together on a specific topic. Or (in)formal boards of teachers, parents and students (either combined or in separate boards) with the explicit task to evaluate the schools’ quality every year. Furthermore, we should not forget that the staff in a school is more than a collection of teachers. It is important that support staff, such as special needs educators, care coordinators and those with managerial positions (like the school director) are included in these structures as well (Romijn et al., 2021).

School culture. Not just the formal structure, but also the more informal school culture is worth considering. As CPD should have a continuous character, teachers would benefit from a school culture that supports learning and development. Teachers should be supported by managers and colleagues to engage in CPD activities. Moreover, the school should be a safe environment in which teachers feel comfortable to reflect on themselves, to give feedback to others and to invent and try out new ways of working. A school culture where there is strong leadership but also a shared responsibility for development has a positive impact on the school quality (De Jong, 2022). This means that teachers try to motivate each other to develop continuously and that they collectively combat resistance to change. Moreover, it is about every teacher feeling like they can learn something from their colleagues, but also that they bring something to the table themselves. For instance, teachers with more experience are usually more skilled, while newly trained teachers tend to have more up to date pedagogical knowledge (Alkharusi et al., 2011).

Let’s pause and reflect

After reading about the importance of thinking of the school structure and culture in CPD for diversity sensitivity, it is important to reflect on your own school and then make some plans.

- How would you describe your school culture?

- Do you believe that there is enough administrative support for teachers’ CPD?

- How would you describe the cooperation between the teachers?

- How would you describe the existing CPD teams in your school?

- What are the areas to be improved?

- How can you and your teacher group contribute to this improvement?

School policies. Finally, a school is not without limits and all teachers must navigate their work and development within certain boundaries. There are regulations and policies they need to abide by. These policies can be created by the school or school board, but also by local or even national entities. CPD activities are ineffective if they are not aligned with these policies and teachers lack empowerment to implement new ways of working (Brown et al, 2016; Daniel & Pray, 2017).

Imagine a teacher that notices their multilingual students struggle with their literacy skills. This teacher is looking for ways to support their students and they find an online seminar that gives the teacher new knowledge on how literacy skills develop in multilingual students. The teacher learns that encouraging them to make use of all their language knowledge (not just their knowledge of the majority language) is beneficial for these students. If the school has a policy to actively ban the use of minority languages in the classroom, the teacher will not be able to enact on their newly gained knowledge, hindering the teacher’s (and students’) development. Thus, CPD should take these boundaries into account if we want change to be sustainable. Again, including key persons (like school directors) is crucial here as they often have the necessary power to push boundaries.

Let’s pause and reflect

Let’s go back to Alex’s case where the intersectionality of his identities makes his education experience more challenging for him and puts you in a more advantaged position. You are a group of teachers trying to improve the school culture and make it a more inclusive place so that you can support Alex and all students. So, think about the school policies now:

- Consider your role as an educator in influencing and shaping school policies. How can you effectively convey to administrators and other decision-makers the needs and benefits of inclusive policies for students with intersecting identities, such as Alex?

- How can you work with colleagues and school administrators to identify and address policies that may impede the development and well-being of students with intersecting identities? How can a shared comprehension and commitment to inclusiveness be fostered?

- Regarding policies, consider the significance of ongoing professional development. How can you ensure that CPD activities align with existing policies while simultaneously challenging and transforming policies that inhibit inclusive practices?

- What steps can you take to cultivate a culture of continuous improvement and learning in your school’s community?

Creating optimal conditions bottom-up and top-down

As a final remark, the described conditions above are created by both top-down as well as bottom-up processes. For instance, school leaders should take the responsibility to provide sufficient resources and create a school structure and culture that supports CPD. Simultaneously, teachers play a major role in the school culture and can take agency in shaping the organisation structure as well. Moreover, they can search for creative ways to engage in CPD, even when resources are limited. This combination of top-down and bottom up even applies at policy level. Policies that heavily support the development of diversity sensitivity have a strong top-down impact on teachers’ CPD (DeJaeghere & Cao, 2009). CPD can be hindered when the policies themselves are not inclusive or (implicitly) create inequalities (Leeman & Van Koeven, 2019). In that case teachers should try to include key persons in the schools to find ways to push the boundaries and create a new reality from the bottom up.

Conclusion

As detailed in the previous sections, diversity sensitivity is crucial for creating inclusive school environments . Many teachers, probably including yourself, need a higher sensitivity towards diversity in the classroom. CPD plays an important role in achieving this. This chapter has shown how your behaviour in the classroom is shaped by your belief system and what activities you can undertake to change both your beliefs and behaviour. Moreover, you have read that CPD can take on many forms, but not all forms are equally effective. What matters most is that you engage in CPD activities that are contextualised and well embedded. This means that the activity should fit with who you are, where you work, what you already know and what you want to achieve. In addition to engaging in individual CPD activities that align with your personal goals and context, it is essential to involve your school and colleagues in the process. By actively collaborating with your school community, you can create a significant and sustainable impact on student outcomes. Remember, CPD is not solely an individual endeavour but a collective effort that extends beyond the confines of your classroom. By embracing collaboration and leveraging the support and expertise of your colleagues, you can foster a truly inclusive educational environment. This way you create the biggest and most sustainable impact on student outcomes.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

After reading about the importance of Continuous professional development, it is important to reflect on your own school, your culture, your reflective journey and your CPD needs

- How would you identify your CPD needs after reflecting on this chapter?

- How would you embed CPD learnings into your practice?

- How would you build an ethos and culture of group CPD learning within your classroom or school?

You have been on this reading and reflection journey together with your colleagues in your school. Thank you for noticing the reality and needs of your students along with your professional development needs as teachers. We hope that the examples and questions have helped you relate the information with your experience and practices.

Your CPD journey only begins here. There is so much to learn about diversity in our schools. Your CPD journey with your community is going to be an enriching, ongoing process as long as you follow the essential strategies for teacher learning, pay attention to the contextual factors in your school and community, continuously reflect on your thinking and acting and be committed to become sensitive to diversity in educational settings.

Here are some resources that might help you. Select one of these links to read and maybe share with your colleagues: If you want to do further reading on the topic, here are some resources that might help you. Feel free to look for more and share them with your colleagues:

- OECD – Educating Teachers for Diversity: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/educating-teachers-for-diversity_9789264079731-en

- UNESCO Online Course on Equitable and Inclusive Education: https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/unesco-launches-professional-development-online-course-equitable-and-inclusive-education

- OECD – The Lives of Teachers in Diverse Classrooms: https://one.oecd.org/document/EDU/WKP(2019)6/En/pdf

- University of Antwerpen – Diversity Sensitive Teaching: https://medialibrary.uantwerpen.be/files/2848/545b0db1-332a-4554-af2b-1eb574ba8f55.pdf?_gl=1*wwm1kv*_ga*MjA5NDM5MTYwMy4xNjg3NDQ1NTY0*_ga_WVC36ZPB1Y*MTY4NzcwMjgwOS4yLjAuMTY4NzcwMjgzMS4zOC4wLjA.&_ga=2.145221620.1188588363.1687702810-2094391603.1687445564

- ATU – Intersectionality Guide: https://www.atu.ie/sites/default/files/2022-10/Intersectionality%20Guide.pdf