Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Democratic Schools: How they work and why they are cool

Halil Han Aktaş; Abdellatif Atif; Andreas Hinz; and Konstantin Korn

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

The backbone of Democratic schools

“This is an example of our experience from a democratic School in Hadera. When the school was established in 1987, there was no clear educational programme. We came with ‘a stomach-ache and ideas.’ It was clear from the beginning that there was no obligation for the students to participate in anything. Everything is free and they can choose whatever they want to do. There were some lessons that we offered, but they were not compulsory. There were playgrounds with a football field and a basketball court, and there were Art Centres, where they could go and draw. There were also areas where the students could complete an internship, for example, with a blacksmith or a hairdresser.

Then we also said, okay, we offer the students all of this, but what else can we do? So, then we said, okay, we’ll help them obtain the tools they need to do whatever they want to do. We noticed that the power dynamic between us and the students really decreased because we were not in charge of lessons that are part of a compulsory program, we were not in charge of the overall discipline, but there was a discipline committee. So, what else can we do?

Then the students began to verbalise their thoughts and feelings about certain scenarios that were happening in their lives. For example, a five-year-old comes and says, “my friend, he always wants to decide what we’re playing, and he’s calling me bad names. And I’m not sure I want to be his friend.” Another example is, let’s say an eight-year-old will come and say, “My parents told me that it’s very important to learn maths and English. And if I don’t take these classes, they will take me out of the school. I don’t want to go to those classes.” Also, a 12-year-old comes and says, “I have a boyfriend and he wants us to kiss and I don’t know if I want to kiss. I’m not sure.” Finally, some kids might say, “I really like computers and I’m good at computers and my father works with computers. However, I started playing guitar and maybe I would like to be a musician, and not work with computers.”

Then we understood that it’s not just about doing whatever you want, it’s your choice; choose your friend, you’re free to choose. It’s not as simple to decide what you want to do for the rest of your life. There’s a whole big range of questions here, and that’s the place we are needed because before you understand what you want to do and enjoy it, you must build an inner self and understanding of what your values are, not moral values. What is important for me when I make decisions? Then I decide what things are most important to me, for example, friendship, play whatever I want to play, be connected to my boyfriend because I like him, or to say, okay, I don’t want to kiss you. Also, what is the most important thing for me to build my point of view about the person instead of only listening to what’s around me. A point of view that considers my parents, my culture, my neighbourhood, and not just what’s popular with my friends. This is a large inner piece that needs to be built and it’s not easy to build it. That is where mentoring came in and this is why mentoring began to be the most essential part of our work.

This is why mentoring became the backbone of our practice. However, there was also another layer in mentoring. Mentoring is one of the best ways to apply human rights. If we want to apply human rights then mentoring is the best place where you say whatever you think is important, you think about the main areas to you and then we discuss it. I really want to listen to it. I really want to see what is important to you. I also want to see and listen not just to what you say or do, but to what’s behind it and what’s under it. I really want to make your existence visible. I want you to be safe. I want you to feel sure. I want you to be open. These are your human rights. That’s children’s rights. This can all occur through mentoring. This is why mentoring, in my opinion, is the backbone of democratic education.”

Dror Simri, teacher, psychologist, mentor and mentoring supervisor in Hadera Democratic School and at Kibbutzim College for Education Tel Aviv, Israel

The need for more democratic schools

Traditional systems of education and schools are linked to the idea of measuring and grading children[1] by more or less the same standards. Therefore, it tends to divide young people into groups of successful, or unsuccessful, based on predetermined definitions, and associates these statements with chances in their future life. These decisions are not fair and not grounded on their actual performance, highlighting the misleading nature of neoliberal output-oriented (meritocratic) orientation. They are, in fact, more linked to socio-economic backgrounds, structures of discrimination, and societal power relations. Therefore, they can’t be inclusive. Most of the time, traditional systems of education and schools are also defining what and how to learn through fixed curricula. Those fixed standards are defined by experts, influenced by societal power relations, and linked to dominant wisdom. Therefore, marginalised wisdom, individual interests, needs, and desires are likely to be ignored. Prescribed curricula therefore stand against the ideas of inclusion and anti-discrimination. It is not by accident that the lyric ‘We don’t need no education’ from Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall’ has widespread and enduring appeal among young people across various generations.

Initial questions

- How to overthrow structural disadvantages for inclusive education?

- How do democratic schools solve those structural problems?

- How could traditional education be influenced by democratic schools to work on those disadvantages?

Introduction to Topic: what idea could stand behind democratic schools?

Imagine a school where everyone can decide what to learn, when to learn, where to learn, how to learn, and with whom to learn. That’s very close to the definition of democratic education from the European Democratic Education Community (EUDEC, 2005). These schools exist in many countries, and they are quite successful.

Imagine a school which has no classes, no grades, no fixed timetable, no fixed curricula, no fixed subjects. However, this school has a space for activities. It has lots of ateliers, maybe for music, for art, for theatre, for languages, for anything you could imagine.

There, children have the chance to be subjects of learning instead of objects of teaching. Or in the words of the German critical psychologist Klaus Holzkamp (1995, p. 558): It’s leaving the “defensiver Lernweisen” (defensive mode of learning) where you primarily react to the impulses of others, mostly adults, building strategies to survive in school. Instead, it is moving to an “expansive mode of learning” where you can go delve as deeply or as broadly as you want into a subject matter. So, you become responsible for your own learning and you get support from others.

Some time ago, I saw a video from the famous jazz bass player Avishai Cohen and his new trio. There was a woman, born in 2000 playing the drums, her name is Roni Kaspi.

She played the drums in such a fascinating, virtuosos, and complex way that I immediately thought she must have been in a democratic school and have been able to learn and practice drums during her whole school time. I was right; she grew up in a democratic school, and later she attended a conservatory and went on to learn the drums.

So, reflecting the vision of such a different school – maybe this vision could be a dream school, or it also could be a nightmare school – it depends on your perspective.

Key aspects

What are the basic principles of Democratic Schools?

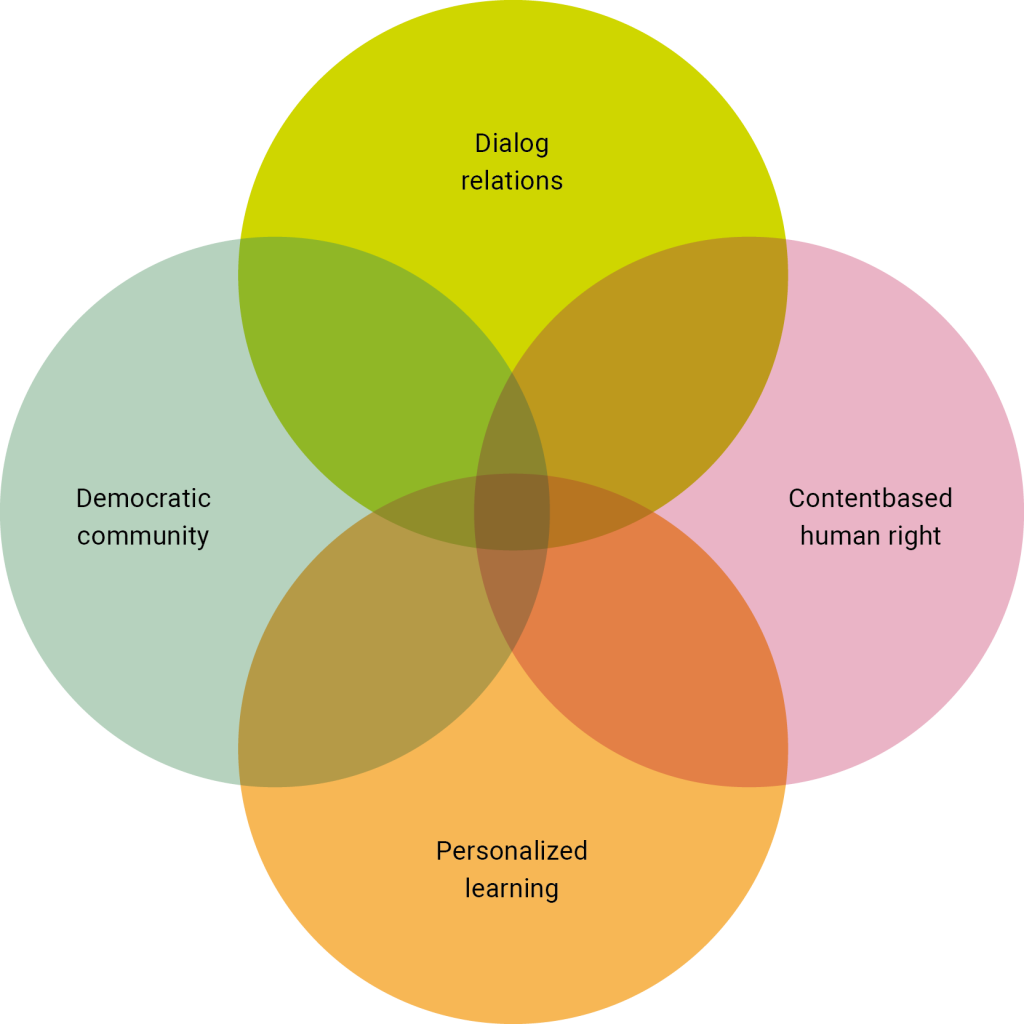

Following Yaacov Hecht (2017), one of the international pioneers for democratic education, it is clear that every democratic school, of course, is different. If there are two the same, one of them has stopped thinking! However, there are four basic principles, and we will give you an overview of these four principles (see Fig. 1). Later in this chapter, we will discuss these in more detail.

Figure 1: Basic principles of Democratic Schools

Dialogic Relations

Dialogic relations are the basis of everything in Democratic schools. There are practices of a partnership culture instead of a domination culture (Eisler, 2000democratic; Eisler & Fry, 2019). There are no people – traditionally mostly adults – who tell others what to do and how to do it. Instead of that, there is a culture of talking on the same eye-to-eye level. So, they try to reduce or to eliminate adultist tendencies. They practise what Martin Buber (1999) called a “ich-du-Beziehung” (me-you-relationship). In this, there is a holistic view of the whole child. It’s not just focused on some ‘mathematics problems’ as the exclusive aspect. So, in dialogic relations the whole person is in focus, and how the whole person thinks about who he or she is.

In this context, we see the heart of dialogic relations in mentoring (see the chapter about → Mentoring). Every child chooses a mentor, usually for a year. It is not the task of the mentor to say what the child should do or how they should behave. This understanding is not about case-management or strategic support for carriers. Instead, it is about thinking together with the child about who the child is, and in many situations, there are some “unconscious backstages” (Goffman, 2010 ), that are bringing the child to some decisions and the child doesn’t realise it – and here the task of the mentor is to ask if the child wants to think about it, always showing respect for the child. Of course, the decisions still belong to the child. It is not about taking away the decision or taking away the power of the child. This task is quite challenging, especially for pedagogues, because many of them are used to taking over, to guide children and teach them something. Therefore, dialogic relations has mentoring at the heart of it.

Personalized Learning: Individual and collective learning

From our perspective, personalised learning is based on a balance of individual freedom on the one hand and the formation of a common social space on the other. Personalised learning doesn’t mean that every child gets an individual programme of work for the next week or month, like in an open-plan office where no collaboration is needed. There is a lot of space for collaboration with others. So, the idea is a connected combination of collective learning and individual learning based on the free will of everyone.

For example, a 15-year-old boy could be extremely interested in black holes, and maybe there is an eight-year-old girl who hears about that and says: Oh, that’s also interesting for me. Then maybe there is someone 17 years old who also joins the group. So, there is a constant change and supplementation of autonomous and common interdependent situations. That’s what personalised learning means.

By collective learning, we don’t mean to learn in a collective; we mean learning as a collective. A common misconception about collective learning is that everybody should learn the same things at the same time, in a uniform way. Learning as a collective is not just about collaboration between individuals to explore and learn about specific topics. It is more or less learning as a group, for example, to solve conflicts or to support someone or something as a group. If you learn how to solve a conflict as a group, it is not just through collaboration, you have to learn how to inquire about a solution as a group also. Therefore, the solution changes, if members change and the group – the collective – has to find new solutions that fit all. Therefore, you grow not just as individuals, but also as a collective. Another example would be if a group of children learns how to support members and assures this support not just through some other group members but as a collective.

Democratic community

Almost every democratic school has a school assembly, and it works under the principle of “one person, one vote,” based on the equality for everyone, like in the former motto of the ANC in South Africa: “one man, one vote.” The school assembly makes every important decision connected to the school. Also, before collective decision-making, there will be a lot of dialogue, or controversial discussion, paying attention to diversity with different perspectives, different opinions, and different interests. One thing is very clear to us: the majority in the school assembly are children. That changes the power structures. However, there is the question of how to decide democratically – by majority, by consensus, or maybe by “sociocratic consent” (Owen & Buck, 2020 , p. 11) which means ‘good enough for now, safe enough to try’.

The school assembly is supported by some committees. There are a lot of different committees. Most democratic schools have a financial committee, some may have a committee for journeys, a committee about juridical questions, a committee about staff, and some may have more. Children make up the majority within these committees, supported by adults as facilitators. The role of the adults is to make sure that every child – even the young ones – understand what’s going on. It’s not about taking the power away from children.

For example, if one child is extremely interested in the finances of a school and learns a lot about that in mathematics, they also get an opportunity to learn about it through life experiences in the school. Whereas in most state schools, children must learn some mathematical techniques without the connection of life experiences. However, here it is really connected to life in the school. This creates a wonderful opportunity to learn so much in mathematics. Another example is, in the committee about staff, one big question is about hiring and firing adults. Children also make up the majority in this committee. So, in many democratic schools the question of ‘is it true that children could decide about hiring and firing of adults?’ The answered is ‘Yes, of course.’ However, it never happens because if there is an adult who offers something for learning and nobody chooses it, this adult will start to reflect about what’s going wrong. So, there is no need to fire someone.

Another aspect of the democratic community is that there is no fixed timetable. Every child decides their own timetable. They decide how many lessons per week they want to take (often around ten), and which lesson they want to have. Indeed, the cliché of boys playing football for years (and “doing nothing all day,” a documentary film by Hentze, 2015) can be a reality in some cases. So, a big question could arise about the patience of parents: How long are they able and/or willing to wait until, for example, a child starts to learn how to write. Mentoring is also an important part of this.

There is also another aspect that we believe is important: boring time. At a conference, children from democratic schools shared their experiences: Oh, it was always interesting, there were always interesting things going on. A former student of a democratic school reacted with the question: Really? So, something went wrong. If you never had a boring time, you never had the chance to find out what’s really really important for you. And what’s really really interesting to you. You need boring times. To make it a bit clearer: It was not about being bored like in many state schools, where every Tuesday at 10.30 you have to be interested in biology – and if you are not, that’s boring, one could say ‘cold boredom’, because you are forced to be there. Boring time in a ‘warm’ sense is a time where you wait to find out what’s really important to you. It is ‘warm’ because you can finish it when you have found out what is really, really interesting to you for the next time(Boban & Hinz, 2016).

Content based in Human rights

The fourth basic principle is that the content is based on human rights and especially on children’s rights. They are formulated in the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC; UN, 1989) which is based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that children are human beings, having human dignity, and human rights.

There are three aspects in human rights education (Gerber, 2011; CoE, 2018; CoE 2020, 19; Tibbits & Sirota, 2023, 54; UN, 2011). One is “learning about human rights” which involves acquiring information and knowledge. The second is about “learning through human rights” which aims at learning processes themselves by accepting and basing them on human rights – for example, the right for leisure or the right to play, also in secondary school age children. The third is “learning for human rights,” which is about attitudes and actions. This could be a tricky one because it could be a starting point for being influenced in a manipulative way by adults: You have to do something for human rights. Also, of course, that would be dangerous because manipulation is an excellent adultist strategy.

The consensus behind this topic is that it is not only about information and knowledge about democracy, but also about the preparation for life in society following school. A lot of questions arise from this. One of them is, how far the influence of parents and their idea for a ‘good future’ of their child can be accepted (Macleod, 2023: 355). Another is about how to be critically aware of any discrimination considering the “long and ugly history of racist and sexist discrimination in the provision of education to children” (Macleod, 2023: 354), additionally questions about classist and other aspects of discrimination (Haruna-Oelker, 2022) – and no one is free from these.

There is also another important discussion – different human rights can be in conflict with each other. For example, is it a violation of children’s rights to force them to go to school? Or is it a human right to go to school? Or both? The answers to these questions are quite different (Graner, 2023).

Interim conclusion – core aspects of democratic and inclusive schools

From our perspective, it would be functional that schools become places with such a high potential and attractiveness that everyone loves to be there and has the chance to fall in love with learning.

At this point it makes sense to think about the connection between democratic and inclusive schools. Both seem to be highly linked:

- Both are based on children’s rights.

- Both are radical approaches, so – despite the all-inclusive and democratic rhetoric – they are not part of the mainstream.

- Both are fighting against discrimination, marginalisation, and othering.

- Both highlight the “beauty of difference” (Haruna-Oelker, 2022 ).

- Both build on participation.

- Both aim on a balance of individual learning and a common creation of a social space.

- Both try to make children – or better – keep children as subjects of learning.

Democratic education without inclusive education stays selective, inclusive education without democratic education stays hierarchical (Simri & Hinz, 2021; Hinz, 2023). Therefore, one without the other is neither democratic nor inclusive. They are linked inseparably if they have any transformative claim.

Why Democratic schools now?

Why do we need democratic schools now? Although the answer might sound theoretical, it addresses concrete and interconnected difficulties where both democracy and education find themselves. We think that democratic schools have the potential to keep democratic and educational projects alive and vivid.

Regarding the crisis of democracy, political debates seem to be replaced by market calculations and planning. According to this logic, political contestations are useless, and thus we should only focus on practical and realistic financial economics (Mouffe, 2013). Words such as, critic, revolt, change or progress that have drawn the democratic horizon of Europe for the last centuries seem to be replaced by one word, which is: consensus and conflict foreclosure (Mouffe, 2005). The promise behind that is a foreclosure of political (often labelled as violent) discourse. However, an attentive look at this may be able to show its hidden politics and uncover the damaging results it may have for the democratic project inside and outside of schools (Atif, 2021).

We can see this concretely in the context of our interest here, the one of schools. Many right-wing parties seem to use this logic of the market to introduce politics under the excuse of being politically neutral and end up being very political against many groups. Take for instance the refusal of sexuality education in Ontario under the slogan Maths not masturbation! (Bialystok et al., 2020) or the refusal of teaching the history of slavery in Brazil by the movement that its name represents its claims, School Without a Party (Oliveira, 2022), or how in Germany the right-wing party ‘Alternative for Germany’ could not find a better way to present its position towards education than a movement called Neutral schools. Such movements use this logic of political neutrality to negate the rights of many social groups that find themselves in unjust situations. According to this, populist movements argue that schools should abandon the emancipatory project and aim at schools that are exclusively interested in the development of productive skills, lifelong learning, and productivity.

We consider that democracy, as the current rise of authoritarianism in several countries shows, is not a guaranteed state. Instead, it is a project that needs to be protected and defended (Hinz, Jahr, & Kruschel, 2023). The protection of democracy can be done through democracy, which reveals and keeps the core of democracy alive. This core is the assumption that once we move from our private spaces to those of living together, our projects are meant to be different and contrasting, and that this is not a limit for democracy but the reason why it is needed. By accepting this situation and trying to deal with it, we can keep the democratic horizon possible. In such moments of being able to dialogue, decide, contrast, argue, and articulate, we can be at the heart of democracy rather than closing it with projects that present themselves as post-political.

It is in these contemporary elements and factual characteristics of the relation of schools with their economic and political context that we look at democratic schools as an emergent necessity to both defend the democratic and educational projects. As presented before, democratic schools are built on the principles of democracy, equality and they are primarily concerned with leveraging them. Democratic schools function through an encouragement of questioning, debating, and articulating. While in traditional schools these may seem like only ideals that are not constantly pursued, democratic schools put them at the centre, from the very format of classroom setting until assessment and evaluation are organised around the principle of debate and freedom. Hence, children in schools have the right to choose what and how they want to learn, and for democratic purposes, they are even encouraged to think about their needs to articulate the demands of their communities.

In an age where the ultra-prioritisation of learning is an input-output process, the reasons for the existence of democratic schools may seem alien to what schools should be. Nevertheless, a closer look at recent developments in educational theory shows how much the principles of democratic schools are making their way back to the conception of how traditional classrooms should function. Theoreticians such as Snir (2017), Ruitenberg (2010), and Atif (2023) argue for schools open to the acceptance of a state of contingency where every social activity finds itself and that reflectively, schools should offer spaces where children and adults can articulate political and identitarian differences instead of preaching them.

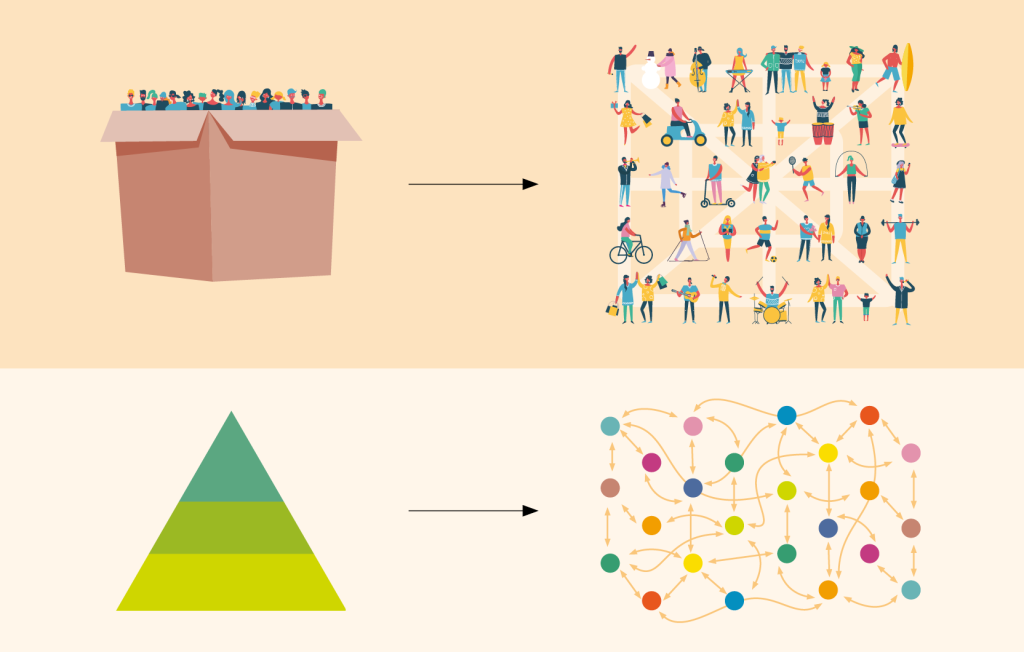

In the discourse about democratic education, there are two main aspects of fundamental criticism of the international democratic community on traditional education, which both constitute structural violence (Ram, 2009). They can contribute to sharpening the understanding of democratic education (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Two main changes from traditional to democratic education

First, there is the construction of two parts of constantly changing and expanding world knowledge, symbolised as a flexible bubble. In traditional education, experts put a box in it by defining a fixed curriculum. This makes knowledge important, which is included and makes excluded knowledge unimportant[2]. So, it does not accommodate the individual areas of strength of every individual person. If an individual is extremely interested in windsurfing, traditional education will exclude this from the ‘important knowledge’ into leisure time. In contrast, a democratic school will fully accept this as part of the uniqueness and the areas of strength of this person. So, the knowledge of the whole world is potentially important for individuals as well as for society in general.

Second, in the box of the fixed curriculum, there isn’t just a box but a pyramid. This means that traditional education constructs a few excellent, many mediocre, and even more weak students by measuring them all with the same hurdles. Students have to climb over them for the next level of education – with all the well-known organisational procedures. Democratic education criticises this logic of pyramids fundamentally and replaces it by a system of connected circles on the same level which – again – contain individual and collaborative learning processes in the sense of personalised learning (see above).

These two main criticisms of traditional education get even more importance since nowadays, education is increasingly being approached with a market-oriented view, undergoing a commodification process where economic outputs in education are preferred over the holistic development of individuals due to the influence of neoliberal ideologies (Apple, 2004; Hill & Kumar, 2008). Standardised tests and accountability measures, which are used to discriminate among students to reach these economic outputs and are assumed to enhance efficiency, are being criticised for transforming education into a test preparation process. As such, education is reduced to measurable outputs and productivity through a reductive approach, stripping it of creativity and broad societal, cultural, and ethical dimensions. It seems that structural violence in traditional education is being increased by neoliberal approaches.

How do democratic schools function?

In this part we focus on the four basic principles from mentioned earlier in this chapter, again by deepening, concretising, and making them more specific.

How to build dialogical relationships in democratic schools?

To understand how a democratic school operates, it is helpful to begin with the concept of dialogical relationships in these schools and how they are established. By ‘dialogical relationships’, we refer to interactions where both parties engage directly with each other, communicate face to face, eye to eye, knee to knee, and meet on equal grounds (Freire, 2005; Rietmulder & Marjanovic-Shane, 2023). From this viewpoint, the first step is recognising children as genuine parts of school communities. This can be initiated by offering positive channels of communication and showing genuine respect to all members actively participating in the school. The goal is to shape a space where everyone’s voice is valued. This means building learning environments that emphasise these principles, and turning schools into places where collective and inclusive decision-making processes thrive, thus giving the authorial agency to children for their learning (Neill, 1960).

A practical example of this is ‘sociocratic circles.’ These are essentially self-directed, voluntarily formed, semi-autonomous groups that come together for decision-making (Strauch & Reijmer, 2018; as showcased in the documentary “school circles” by Osório & Shread, 2018). Imagine a scenario where a group of children voluntarily assembles because they have identified a challenge within the school and want to address it together.

Here is an example from a particular democratic school in Turkey.

The adults posited that fostering children’s participatory skills might be enhanced by offering them hands-on experiences in settings akin to school councils. Consequently, a platform was established where these young minds met weekly to deliberate on pertinent school matters. However, as time passed, these elementary-aged pupils felt the weekly gatherings to be excessively recurrent. They began to find these sessions monotonous, often engaging in discussions devoid of any accompanying activities to enliven the experience. This sentiment led them to initiate a sociocratic circle dedicated to evaluating the structure and frequency of the school council meetings. Within this circle, many questions and suggestions surfaced: “Could we possibly reduce the frequency of these meetings? What if we incorporated engaging games at the onset of each session?” After these deliberations, they envisioned a reformed model of the school council and proceeded to present their proposals to the broader school council. Upon careful consideration and discussions, the collective consensus emerged: “Indeed, a shift is required. Let’s change it to bi-weekly meetings and infuse a gaming element at the start. The objective would be to foster warmth and enjoyment before transitioning to the more serious discussions.” Implementing this revised approach proved successful, resonating well with the children.

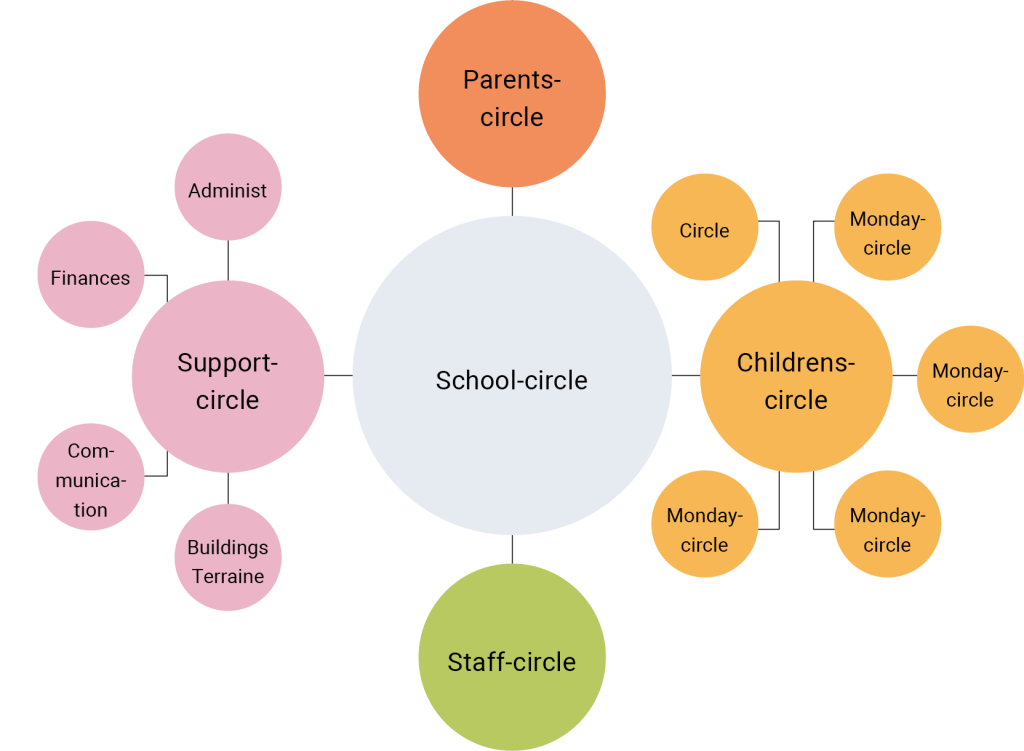

This entire excerpt epitomises a scenario where children, by amalgamating diverse perspectives, actively shaped their school life. Another option could be to organise the whole school in sociocratic circles. In the documentary, there is an example from the Netherlands (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Circle-structures of the sociocratic school De Frije Ruimte

The central school circle with members of all groups in this school is connected to other circles: the children’s circle (connected to age-oriented group circles every Monday), the staff circle (called the learning facilitator-circle), and the support circle (again connected to circles about administration, finances, buildings and terrains, and communication). Children have access to most of the circles except those for parents and staff. All circles are connected by two (children by three) members who care about the flow of information between them all. Also, they all have specific procedures and roles for talking and decision-making.

For democratic schools to thrive, it is vital to embrace dialectical thinking. Essentially, when we reflect on schools, we are looking at diverse communities brimming with varied beliefs, interests, needs, and viewpoints. If we solely rely on the premise that one person should guide the school’s direction, we risk overlooking these rich differences. Rather than that narrow approach, it is beneficial to adopt a dialogical mindset. This means understanding and valuing the range of voices and perspectives present in our school communities. Instead of sidestepping challenges or disagreements, it is about creating a safe environment for children in school to freely participate in decision-making and collaboratively address issues (McDonnel, 2014).

To foster such an open environment, it is essential to factor in the social and emotional aspects of learning (Cohen, 2006). For example, before any productive discussion can take place, there is a need for trust among participants. When trust exists, it paves the way for mutual respect. We also need to create rooms and opportunities for children to actively listen to their peers. Active listening allows for constructive conversations, fosters collaboration, and recognises diverse viewpoints. For these dialogues to truly resonate, participants need to feel confident in themselves, be in touch with their emotions, and be equipped to share their thoughts and listen to others in group settings (Read, 2021).

Another key point is the importance of joyful learning (Waterworth, 2020). For learning to be truly engaging, children need to have the autonomy to shape their educational journey (Freire, 2005; Griffiths, 2012). To successfully do this, children also need certain skills and attitudes, like critical thinking, setting goals, regulating their own progress, and taking initiative. These attributes empower children to steer their educational path. Moreover, when disagreements arise, it is these very skills that enable children to articulate their ideas, present alternate views, or stand up for their beliefs (Dobozy, 2007; Slater, 1994). These social and emotional elements are crucial in democratic schools. Without them, any rights or opportunities we offer children might only be symbolic, appearing good on paper but not truly realised in the actual school environment.

How to organise learning in democratic schools?

Delving into the etymological roots of certain concepts can illuminate the potential pathways that can be adopted in democratic schools. The term “democracy” is borrowed from the Greek, consisting of ‘demos’—representing the people of a shared territory, although in ancient Greece, this did not include women, children, or slaves—and ‘kratos,’ which signifies the power or capacity to govern. Bringing these together, democracy encompasses a collective of individuals striving for individual and mutual growth. When examining the term “curriculum,” its origin traces back to the Latin word ‘currere,’ suggesting a journey or perhaps an individual’s unique trajectory. The curriculum, at times, is perceived as rigid and predetermined; yet, it can be approached with flexibility – for example the National Curriculum of Iceland – which permits learners to engage with it selectively or even bypass it entirely (Carr, 1998; Hinz, 2024). For instance, instead of being accepted as a predetermined blueprint of the experiences to take place at the school, curriculum can be defined as “a set of events, either proposed, occurring, or having occurred, which has the potential for reconstructing human experience” (Duncan & Frymier, 1967:183). Merging these ideas, a democratic curriculum embodies the spirit of communal living, emphasising collective progress by elevating each member’s individual growth. These concepts can be viewed as complementary. An offer-based curriculum, influenced by members of the school community can be designed and implemented in democratic schools.

When planning learning in democratic schools, it is beneficial to start with the childrens’ previous experiences by considering child-centred curriculum perspectives (Brough, 2012). Why? When we bring these children together, our goal is to foster connections among them. To do this effectively, we need to be familiar with their past experiences, interests, and needs. By using this knowledge as our foundation, we can shape the learning in democratic schools, focusing on integration as a key element of curriculum design (Beane, 1997). This approach is what gives these schools their unique and meaningful learning atmosphere. In such environments, the individual benefits and collective well-being are aimed to merge seamlessly. As children achieve their personal social-emotional goals, they naturally become more cooperative, understanding, and respectful — qualities at the heart of democratic schools. Keeping these factors in mind is invaluable when organising learning in such settings.

In democratic schools, it is also essential to blend both the humanities and science for a well-rounded education. This is not just about broadening knowledge; it is about nurturing both intellect and empathy in children (Dewey, 1930). Democratic schools are not just about academic growth. They are communities where children are encouraged to connect and thrive harmoniously together. Of course, the social and emotional learning components of these schools are vital. To genuinely prepare children for the broader democratic society, we need diverse activities that nurture a range of skills. In a democratic school, the goal is to grow individuals who can keenly observe and analyse their surroundings and, using that understanding, offer fresh insights to their community; thus, a holistic approach touches on both their emotional and intellectual capacities (Ricci & Pritscher, 2015). Therefore, a “curriculum” in democratic schools should give equal weight to the humanities, arts and sciences. It is about fostering a complete, balanced learning experience for every child. However, it is worth noting that the way democratic schools handle the curriculum may change in their own contexts, and there are democratic schools that do not employ a specific curriculum intentionally.

In planning lessons for democratic schools, using tools like mind maps or curriculum matrices can be beneficial to allow us to visualise the links between academic subjects and the effects of how we handle them on both a child’s intellect and emotions. Unlike traditional schools, where the primary focus may be a teacher passing on knowledge, in democratic settings, we recognise that everything we do elicits reactions in children, both mentally and emotionally. So, it is essential to be conscious of our teaching actions and their broader impacts on children. By understanding this, we can tailor our approach to nurture not just academic skills, but also emotional and social well-being.

In democratic schools, valuing diverse viewpoints is essential, reflecting our unique experiences and backgrounds. It is not just about harmony; disagreements, or dissent, have a place too (Matusov & Marjanovic-Shane, 2015). These varied experiences can often become powerful learning moments. So, while mutual respect is crucial, so is acknowledging the importance of dissent. However, as adults, we have a task to ensure children feel safe when expressing their opinions. If we are not careful, disagreements can become destructive. It is our responsibility as adults to create a safe space where children can discuss differing views openly and without harm, with the help of support and guidance (Orzel, 2013).

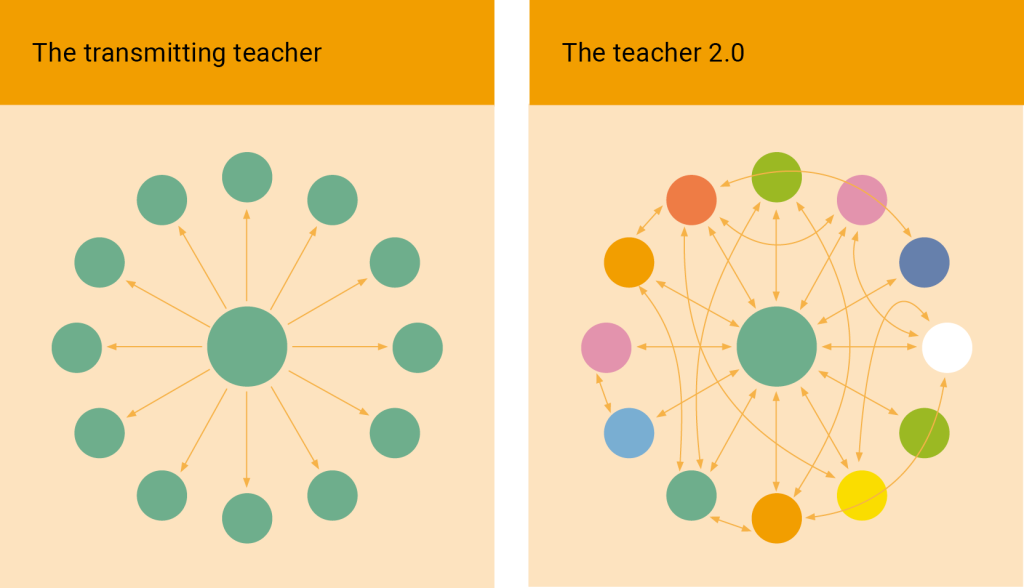

In traditional schools, students often find themselves sitting and listening to teachers, essentially in a state of stillness. They do not actively engage or decide their learning path; they are mostly passive, enduring what might feel like a “cold boredom.” However, a democratic school offers a different approach. Instead of this passive learning, children are given opportunities to navigate their school experiences, whether they be joyous or filled with conflict, and they learn from these lived experiences (Davids & Waghid, 2019). It is about allowing them to voice their views and actively participate in the school environment. Drawing from the German educational approach, ‘arbeitsplan’ or weekly planning tools can illustrate how children can be given autonomy over their learning. By implementing such behavioural-contract tools that encourage self-assessments, we can empower children to shape their educational journey as active participants and organise learning democratically (Pass, 2007). Without such mechanisms, our aspirations for democratic education might fall short. Simply telling kids, “you decide your learning,” can be overwhelming if they lack the tools or understanding of how to go about it. However, by creating semi-structured methods, we may assist them, much like mentoring. Importantly, this reshapes the teacher’s role. Instead of being mere information dispensers, teachers in democratic schools become connectors, linking children in a myriad of ways, a significant shift in role (fig. 4). Plus, children get the unique opportunity to reflect on their learning since they have played a pivotal role in it. Engaging with adults about these processes becomes more meaningful because children can draw on their direct experiences. They can witness their growth and navigate learning using these benchmarks.

Figure 4: Transmitting and connecting role of the teacher

Also, portfolios or learning progress reports are effective tools to organise learning and create democratic spaces for dialogic assessments and feedback in democratic schools (McDonnell & Curtis, 2014). These documents making progress visible for children, they can check what they have learned, and how they learnt it. They can reflect on whether it was difficult or simple. Otherwise, it is just a task to be completed for grading. However, by using this strategy we can enrich evaluation through authentic feedback that strengthens learning. Therefore, it is important to give them a chance to reflect on their learning progress. Also, strategies like the “black market of knowledge” are good examples (Boban & Kruschel, 2015).

The black market of knowledge is a social space in which ideas, topics, and children’s learning are exchanged. They present whatever they want. It may be something they worked on, or they have experienced. This was an idea that some children, brought to the school assembly, and later it was used by student teachers within teacher education (in the Kibbutzim College Tel Aviv, where foreign visitors practised it together with the students).

Such experiences inherently foster a deeper alignment between individual and collective learning endeavours. For instance, following an event like the “black market of knowledge”, some children might gravitate towards the presenter, forming a cohesive group. This group might then pursue diverse learning pathways originating from their own interactions. In this context, the children’s own interests, skills, and needs naturally shape the trajectory of the learning journey, encompassing all facets such as activities and topics. Importantly, this dynamic is not dictated by an external force determining the worthiness of knowledge.

How to develop a democratic school community?

Schools function as complex social entities. They are far from being uniform spaces; instead, they welcome diverse people groups. Thus, for the establishment of a democratic community, it is essential that we recognise and address the varied needs of children. By crafting mechanisms that highlight these diverse needs and cater to them, we lay the foundational aspect of democratic schools.

Moreover, the essence of democratic schools is to offer room for children, educators, and the entire school community to foster autonomy (Taylor, 2017). A common misconception is that autonomy is something that can simply be handed from one individual to another. However, in reality, it is an attribute that grows through lived experiences and social interactions (De Jaegher & Froese, 2009). When children engage in activities, the culmination of those experiences contributes to their cognitive, emotional, and social growth. This engagement and growth through experiences stand central to forming a democratic ethos within the school environment. Committees, for instance, showcase an effective way of distributing power amongst members and collaboratively experiencing it in the school setting.

For instance, the Alpha School in Toronto (Canada) practises a juridical committee. The meetings are organised like a court if there are some children breaking a rule. So, a group of, most of them quite young, children sit together, and just one adult acts as a facilitator, making sure that each and every child is able to understand what was said before and what the case is about. The adult doesn’t influence the content of the meeting or the verdict of the court. In almost every case the verdict is not about punishment but about restorative actions.

Consequently, the objective is to allocate roles to individuals, specifically allowing children to assume responsibility for their surroundings. Integrating the broader community, or the vicinity in which the school is situated, is pivotal. This might involve inviting external individuals to the school or planning outings for the school community. Such initiatives are vital because they facilitate the transference of outside experiences into the school setting. Furthermore, they aid children in understanding the societal norms and codes prevalent in their communities. Ultimately, our goal is to cultivate individuals who are deeply cognisant of the societal fabric they inhabit and reflect on it. Thus, facilitating experiences beyond the school’s boundaries can be quite beneficial.

Another example is from some state schools in the eastern part of Germany during the implementation of the all-day school; though it is not explicitly a democratic school, they were on the way to democratisation. The facilitators from the university asked them to include one person from outside of the school on to the steering group for school development, in addition to children, parents, teachers and other staff. Some of these people had wonderful ideas and practices. One school thought about inviting the mayor, maybe also for strategic reasons, and some had real difficulties in finding someone whom they could include in the steering group. However, in general, it is a good example showing that the connection between the school and the environment or the community around the school is much more intensified. At the end of the day, children are individuals, some of whom might be the mayor in the future. Therefore, supporting them to observe these environments is important.

Concluding on the topic of participation within school environments, the concept “participation” can sometimes be elusive. To clarify, we might consider specific examples of how participation manifests in these settings. For example, when a collective of children take on a decision-making role in school, this is a clear indication of participation. Similarly, if a group of children, perhaps through a school council framework, independently resolve an issue, that too is a form of participation. Another instance might be when children proactively set discussion topics for future council meetings, or initiate new ideas, or even voice their disagreement on a proposed idea, saying “this doesn’t resonate with us.” All of these scenarios exemplify participation.

We can envision participation through these lenses. Feedback mechanisms are equally vital, whether it is from children to teachers, teachers reciprocating, parents to teachers, or even children giving feedback to parents. This significance stems from the fact that it represents mutual observation, active listening, and ongoing communication, establishing a dialogue-centric relationship. Keeping such modes of participation in the forefront can offer clarity on the essence of participation and its implementation in democratic schools.

Here is a final example, from a school in Iceland which is not an explicitly democratic school, but one with a strong democratic tradition and continuous developments over the years (Jörgensdóttir Rauterberg & Hauksdóttir, 2024). Some children had this idea: “Oh, we don’t have enough space and time to talk about some social things. So, we need a new subject in the plan for the next school year.” They brought it to the children’s council and later to the school council. During a visit, the vice principal said: “Yes, they asked for that and we will give it. But we didn’t tell them until the end of this school year. In the next school year, there will be a new subject in the plan.”

So, that’s an example that includes flexibility in curriculum and a huge influence of children in it (Jörgensdóttir & Hinz, 2024).

How to define common goals based on human rights education?

Democratic schools are based on human rights essentially; therefore, they have the common goal to strengthen Human Rights Education (HRE). HRE focuses on the realisation of human and especially children’s rights and has been a growing field since the 1990’s with a big growth in publications (Tibbitts & Sirota, 2023: 56). The most widespread definition is given by the UN in the Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training, Art. 2 (1) (UN, 2011: 3): “Human rights education and training comprises of all educational, training, information, awareness-raising and learning activities aimed at promoting universal respect for and observance of all human rights and fundamental freedoms and thus contributing, among other things, to the prevention of human rights violations and abuses by providing persons with knowledge, skills and understanding, and developing their attitudes and behaviour, to empower them to contribute to the building and promotion of a universal culture of human rights.” As said earlier, three aspects are included: Learning about, through, and for human rights (UN, 2011, Art. 2, 2) and they have an immense impact on learning and teaching.

Internationally, HRE is linked to diverse efforts “to overcome colonialism, the aftereffects of authoritarian governments, structural problems related to poverty, gender inequality, discrimination and interethnic conflict” (Tibbitts & Fritzsche, 2006: 5). In some countries it is also linked “with local and national efforts to fight racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism and the extreme right” (Tibbitts & Fritzsche, 2006: 6). Critical comments, from the Global South, say, there is an “unacknowledged conceptual diversity and ambiguity” (Keet, 2006:1).

Following Bajaj’s (2011: 491) analysis, three main ideological backgrounds can be differentiated:

- HRE for Global Citizenship – aiming for a new global political order with more equality,

- HRE for Coexistence – aiming for healing and reconciliation after brutal oppression and crimes against specific groups, like indigenous peoples in Canada or elsewhere, and

- HRE for Transformational Action – with “radical politics of inclusion and social justice” (ibid.).

This picture of approach does not mean that HRE is in practice everywhere. On the contrary, HRE is still only partially implemented. As the research by UNICEF (2015) shows, 11 out of 26 countries have implemented HRE (more specifically: children’s rights) into their school curricula. In seven countries, implementation only took place in parts, and in 15 countries not at all (UNICEF 2015: 8). There is still no international entitlement for HRE, and therefore, there is no linear connection from signing the convention on children’s rights to the implementation in classrooms. Also, the implementation in teacher education is important, but it is not realised systematically anywhere (UNICEF 2015: 9). Therefore, it is not surprising that in 2010 “HRE is still not widespread, especially in schools” (Gerber, 2011: 247). Nevertheless, good examples exist, for example, in Iceland, “human rights and democracy” are one of six pillars in the National Curriculum (MESC, 2011: 14-22; Hinz, 2024).

One interesting aspect of this field is that almost every literature emphasises the growth of democratic practices and ideas. This begins “in small places, close to home – in the neighbourhood, school, college, factory, farm, or office” (CoE 2020: 403). Some good examples of this are in India where more than 500,000 “inclusive neighbourhood children’s parliaments” are in place where all children of the neighbourhood automatically belong; they themselves decide about the topics and the actions, and they are supported by an adult facilitator (Boban & Hinz, 2020b). This is more than being asked to tell the parliament of the city or the state about needs and wishes once a year, as in many countries.

It is very often stated that this is a long-term process, and it is never finished, and never perfect. Sometimes it is criticised that it needs changes because it is “western-centred and ‘top-down’” (Tibbitts & Sirota, 2023: 58). For example, the role of teachers must change from a declarationist approach to a dialogical approach (2023: 58). However, a reflection of the existing power relations in schools is hard to find, except when a transformational action approach is used with its “radical politics of inclusion and social justice” (Bajaj, 2011: 491). Bajaj writes that with this approach, which is a “critique of power and unequal power relations (local, national, global),” is needed (2011: 491). Otherwise, the research results regarding the very low expectations of children about their influence in school could be validated. With this approach, HRE is quite close to any other transformative and emancipatory learning, “associated with critical pedagogy and Paulo Freire” (Tibbitts & Sirota, 2023: 57). The methodologies can be described as “justice-oriented, decolonising, experiential & activity-centred, problem-posing, participative, dialectical, analytical, healing, strategic thinking-oriented, goal-and action-oriented” (Tibbitts & Sirota, 2023: 57).

It is obvious that the understanding of HRE as a call for transformative actions is very close to the approach we stand for. Schools practising democratic education consequently have a much easier task ahead to abide by children’s rights. For schools on the way to more democratic practices, it is much more contradictory to practise democratic processes in a hierarchical system without balanced power relations. Nevertheless, connecting learning to human rights is a continuing challenge for every school.

One material for the support of HRE is Compass, published by the Council of Europe (CoE, 2002, 2020) and translated into 30 languages, supplemented by Compasito for children from 7 to 13 with 40 activities (CoE, 2007, 2009). These materials want to support accessibility to HRE (CoE, 2020: 26) with a European perspective (CoE, 2020: 29). The heart of the material are 58 activities in 20 global themes for the reflection of human rights and taking action, surrounded by introductions about human rights and approaches to HRE. The “pedagogical basis” is explained in detail (CoE, 2020: 32-36). This includes, among others, “HRE must let young people decide, when, how, and what topics they wish to work on” (CoE, 2020: 33), and the role of teachers has to change to a “facilitator, guide, friend, or mentor, not one of an instructor” (CoE, 2020: 33). Nevertheless, there is no reflection about power relations in school. Instead, you, as a facilitator, friend, or mentor (see above) “need to be very clear in your own mind about what it is you want to achieve; you need to set your aims. Then you can go on to choose an activity that is relevant to the topic you wish to address, and which uses a method that you and the young people will feel comfortable with” (CoE, 2020: 48). Friend, facilitator, mentor? This sounds quite contradictory, here the teacher still seems to be the instructor, setting the frame – and within that frame children are more or less free to decide about their learning, and about human rights. Is this democracy? It seems to be not less than or more than a step towards democracy in a structurally non-democratic institution.

All the content in schools based on human rights is, of course, connected with an anti-discrimination and inclusion approach. It is no coincidence that a lot of democratic schools are part of social movements for peace, for reasonable living, for ecological survival, and/or for a better future. Democratic schools are, in most cases, no idyllic bubbles far away and at the margins of society. Power structures might recreate themselves in democratic schools, so it requires investing time and effort to prevent it (Wilson, 2015).

Therefore, as a final comment on this principle, there is a big need for reflection of power relations. There will always be a big difference between the principles and the realities of societies, and of course, democratic schools are part of society. Hence, it is important to reflect again and again on what a school, or a group, can decide autonomously and what is already decided by others.

What are the specific challenges for democratic schools?

You might think that democratic schools are perfect, but we don’t think that. They are not perfect at all. There are some specific challenges for democratic schools.

In the realm of educational discourse, there is a palpable debate concerning the children’s composition in certain democratic schools, which might show elitist and exclusive children’s body characteristics. Central to this debate is the representation of varying social groups within these institutions. Sometimes it is observed that children from more privileged backgrounds often have a heightened presence in these schools. Intriguingly, some of these institutions took shape during what is known as the ‘second wave’ of democratic schools, a period intertwined with the aspiration to craft ‘islands’ within the broader conventional school framework (Hecht, 2011). These ‘islands’, in certain cases, are cited as practising what some term ‘elitist democratic education’; essentially, they impart democratic values and practices predominantly to children stemming from affluent socioeconomic strata (Sant, 2019). However, it is crucial to note that not all schools fall under this critique. For some, the demographic characteristics of their geographic location play a defining role. Yet, for others, it is the predispositions and financial capabilities of the parents that is changing the situation. Such parents, with more substantial means to invest in their children’s education, exhibit a proclivity towards enrolling their children in private institutions, which sometimes includes democratic schools. This trend has roots in the ‘school choice’ philosophy—a perspective that may compartmentalise education into distinct categories like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ schools, offering the liberty of choice to a select demographic, undermining the ethos of fostering educational establishments that champion democratic values for the collective welfare.

Furthermore, the broader structural landscape of the state’s educational system holds influence. In general, it depends on the rigidity of the state school system. If there is a high rigidity and state schools have big problems with a lot of children, there will be a high percentage of children in democratic schools who have been in state schools, and they changed to democratic schools (Hecht, 2011). Hence, democratic schools could be seen as a good place for children, who had some difficulties in a traditional learning environment or in state schools. For these children, democratic schools could be islands that they can feel secure, that they can feel comfortable in.

There can also be some parents of children with disabilities who may have doubts about democratic schools. Some of them may fear their child could get lost due to the ‘big freedom’ in democratic schools. They may assume the responsive structures their child may need are not there and, therefore democratic schools are not a good solution or perspective for their children. However, democratic schools of course are very able to put structures around a child, for example, they could start with a group of children who are close to that child, and they could think together about how they can establish a good situation for this child through dialogic relations. So, it is not about getting lost in freedom but about creating structures through democratic communities.

There might also be challenges about the diverse cultural backgrounds of teachers, children, and parents linked to the exclusivity of the children’s body. Especially, if these backgrounds affect the way of the ‘right’ and ‘common way’ of communication. As communication is so important for democratic schools, it is a special issue. There are rules of communication that are different in different cultures. Therefore, there are also different understandings of democratic ways to solve conflicts and interact with each other. For instance, most Germans find it disrespectful if they are interrupted. Therefore, they believe, in a ‘good’ and ‘democratic’ conversation, no one interrupts each other. To understand this, you must first know about it. In the German language some important words, mostly the verb, are located at the end of the sentence. So, you must listen to the end of the sentence to understand each other. However, this is not the case for many other languages. The structure of sentences is different, and therefore it is not disrespectful to skip the end of the sentence and jump right to the important subject. That’s one example of how the way of communicating interferes with the way of understanding how ‘good democracy’ works. Another example is, in Turkish, it is a practice to overlap when speaking, and it is considered normal and polite to do this. What we want to show with these examples are that we don’t want to reproduce the dominant use of language and the discrimination within it. However, instead to practise cultural sensitivity in democratic schools, there has to be a precise look at the practice of communication and reflection about it. Practices of talking are so deeply anchored inside us, it is difficult to question and reflect on their roots. This is highly demanding for democratic schools, because dialogic relations are so much the basis for all that is happening inside these schools.

As we can see, democratic schools are not the perfect way to deal with every problem, but they have one big advantage, democratic schools are always in a mode of change. They are more likely to find the challenges of exclusive children’s bodies, diverse cultural backgrounds, and establishing special structures for children who need them easier. They can handle it within their ritualised way of changing instead of first creating change management.

There are many different models of democratic schools and their view of the role of adults and the wider community. Some might argue that adults are just there to wait for the children to come up to them and want to learn or get something, like in the Sudbury Model. Others argue they should offer specific things and be more interactive with the children about what could be learned, like in a common social space. We don’t want to judge which way is better, we just want to highlight there are different ways to practise that aspect in democratic schools. What’s important is the knowledge about the different connections to the community that are implied by different views of adults. Sometimes schools really benefit from the experience of parents. They might transfer their knowledge to the school settings and share their expertise. Through this, they may support children to find their interests and what to learn, but this may also cause some difficulties if not handled well.

In a particular instance from Turkey, a school was established through the initiative of a group of parents. This co-operative school had a foundational ethos: the incorporation of democratic governance. The intent was clear: children should actively engage in the decision-making processes within the school. However, having been the driving force behind the establishment of this institution, parents viewed themselves as the primary stakeholders or the owners of this educational establishment from time to time. As such, they felt entitled to influence areas like the instructional methods, curriculum, and other core aspects of the educational process. This proactive involvement sometimes took on a domineering tone, leading to challenges. The underlying issue was a presumption among some parents that their insights were superior to those of trained teachers.

In discussions surrounding such situations, it is important to remember the professional background of teachers. Teachers undergo specific training and possess extensive expertise in their domain. Regrettably, there are times when this expertise is overlooked or underestimated. However, it is also heartening to acknowledge instances where their contributions are recognised and valued. Regardless, it remains undeniable that they are hands-on professionals in their field. Their role, therefore, requires respect. As efforts intensify to embed democratic values in school environments, it is crucial to emphasise inclusivity. This encompasses the well-being and participation of all of the members of the school community, from the children to the teachers and parents and other staff. Thus, fostering respectful and considerate relationships becomes integral. To foster an enriched learning environment, it is necessary to carve out spaces and opportunities for educators to engage in mutual learning, thereby cultivating a tradition of continuous professional enhancement (Blick über den Zaun, 2011). Such initiatives not only augment teachers’ competencies but also chart a progressive trajectory for their professional journeys. Equally vital is the role of educational institutions in enlightening their surrounding communities about the intricate nature of quality education. By doing so, they can nurture an informed community, fostering greater understanding and support for the educational process (Kim & Bryan, 2017). To encapsulate it, the essence of dialogic relationships is not confined solely to the dynamic between children and educators. It extends to encompass all stakeholders – be it parents, teachers, or children, essentially every individual, both young and old, involved in the educational journey.

Democratic schools may also face criticism for potentially embodying neoliberal and individualistic values in their educational approach. It is worth noting that in numerous democratic societies, neoliberalism either dominates or is steadily gaining ground in the education sector. While some democratic schools push back against this trend, others seem to embrace it. From an analytical standpoint, there are two core challenges with neoliberalism when viewed through the lens of inclusivity. The first issue stems from how neoliberalism conflicts with the ethos of greater participation and self-expression as envisioned by democratic schools. In the neoliberal paradigm, self-expression is geared towards optimising individual productivity within society and its economic structure. This angle risks misinterpreting the personalised learning ideal, aligning it more with the development of individual human capital than with genuine personal and civic growth. The second concern revolves around the neoliberal perspective on democracy and its seeming indifference to the principle of inclusion. Under this model, one’s inclusion hinges on their economic productivity. Take, for instance, the realm of human resources, where there is a belief that diverse teams boost creativity and productivity. Here, inclusion appears to be a byproduct of economic benefit — you’re included because of the added value you bring, not necessarily because it’s a fundamental right (Boban & Hinz, 2017).

What can we do then?

While a multitude of concepts and examples surrounding democratic schools exist, one might wonder, “What steps should I take?” Amidst the plethora of ideas and seemingly flawless models, it is crucial not to be daunted. Remember, no democratic school sprang into existence instantly. This underscores that there is a role for you to play, even if it begins as a modest stride, always keeping the grand vision in sight. A pivotal point to embrace is the understanding of democracy not as a static ideal to replicate but as an ongoing journey of democratisation. It is about amplifying participation, championing inclusion, and continuously challenging societal norms and conventional boundaries.

Diving deeper, consider the dynamics among the three neighbouring households. They, like any close-knit community, might encounter disputes. Confronting these differences, they might engage in intense dialogue, but eventually, harmony is restored. Just as with democracies or our daily interactions, the essence is not an external facade but lies in our interpersonal exchanges. It is not a plateau you achieve and then rest; it is a continuous endeavour.

Crafting a democratic school is essentially a journey where community members actively shape and redefine themselves and their collective identity through their shared experiences over time. The fruits of this journey manifest as more deliberate decisions, practices, and engagement within the community occurs. Central to this idea is the belief that autonomy is not just handed over; it emerges from experiences and in turn, shapes them. These experiences are deeply intertwined with the other core principles of a democratic school. Emphasising the foundation for such experiences, growth involves immersing individuals in certain experiences consistently. Moreover, this growth thrives in relationships guided by specific frameworks. Within the democratic school framework, growth is perceived holistically. Such growth takes root in a community engaged in continuous self-reflection, utilising tools and methods that prompt particular experiences at just the right moments. This suggests growth is a timely process, underscoring the need for patience within the community. This understanding stresses a step-by-step learning evolution and highlights the importance of diverse learning avenues vital for holistic skill development. From this vantage point, the sustainability of these shared experiences is pivotal for genuine growth. As these structured experiences accumulate, paired with guided relationships, it paves the way for the evolution of both individual members and the larger community, and their autonomy and heteronomy.

Every educator, each institution, and perhaps each human being has the potential to embark on the path toward a more democratic educational setting. Democratic schools across the globe did not just appear; they were crafted and continue to evolve. For those aspiring to absorb insights from these schools and integrate aspects into their conventional settings, initiating change could be as straightforward as addressing an existing minor challenge, something already recognised as an inconvenience by peers. The thought could be, “This has become bothersome. Why not rectify it democratically?” An excellent starting point might be the ‘index for inclusion’ (Booth & Ainscow, 2002, 2011). This index presents an expansive list of questions, beginning with hundreds and escalating to thousands, none of which have a single answer. The purpose is to foster collective introspection and dialogue within the educational community, offering a plethora of queries related to the school’s culture, policies, and practices. The emphasis is not on seeking perfect solutions, but rather on discerning beneficial and manageable subsequent steps. At the heart of the index lies the dual aim of diminishing obstacles to both participation and learning, seamlessly intertwining the ideals of inclusion and democracy.

In wrapping up, numerous entry points exist for embarking on this journey. Regrettably, a universal, one-size-fits-all approach remains elusive. The solution should align harmoniously with the unique attributes of each school, the educational milieu, and the encompassing community.

That said, structured methods to foster school growth and professional evolution for educators do exist. For instance, the chapter on continuing personal development offers guidance on collaboratively addressing prevalent inclusion challenges alongside colleagues. Should personal growth be your focus, the chapter discussing diverse teaching staff and role models might serve as an insightful foundation. For those inclined towards initiating more extensive transformations within their institutions, there are two chapters about school administration and about implementation of a democratic policy in different parts of this open access material.

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

To teacher-candidates/students

- Which teaching style of your professors/lecturers do you like? Why? How do they interact with you and your fellow students? Which element is dialogic?

- Which method of learning fits for you and which doesn’t? Why? Which form of learning is this? Individual, collaborative, in a group, etc.

- In which situation did you learn the most about inclusion / about democracy? Who (teacher, peers, yourself) had which role there? Why was that situation possible? What would have made it impossible? Identify the specific aspect that made it impossible and turn it upside down!

To teachers

- What is a problem you and your colleagues could easily face?

- Which question of the index for inclusion surprised you?

- What really annoys you at your school?

- What is the most attractive aspect of a democratic school for you?

- What aspects of human rights education are already part of your practice? What aspects do you wish would be a part of it?

- Where do you give your children space for change in your school?

- How and where are parents and other community members involved in your school?

- How do you give feedback to your children about their learning process? How do children give feedback to you?

Literature

- In this chapter, we use the term “children” in the sense of the Convention for the Rights of Children (UN 1989), which contains children up to the age of 18. Alternatives would have been to say “students”, “pupils” or “learners” but we prefer a term which has a holistic view on the whole person and is not fixed on a specific role, being in danger of ignoring other aspects. The only exceptions are students at university or when the traditional role of students is in focus. The same way the term “teachers” could be problematised - and replaced by “learning assistants”, “learning supporters” or others. A wide field of reflection… ↵

- These decisions are highly linked to power relations in society and thereby tend to exclude marginalised knowledge, for example from wisdom from minorities or about discrimination (Kress, 2022). ↵