Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Differentiation

Silvia Dell'Anna; Jessica Lament; Frank J. Müller; and Yasemin Acar Ciftci

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Sarah, a novice teacher, is confronted with a very heterogeneous class: some pupils have already fully mastered much of the proposed content, while others are struggling. She realizes that the “one size fits all” formula is not only counterproductive, as it demotivates some and leaves others behind, but also ineffective.

She turns to a colleague for advice and receives some suggestions on how to approach differentiated instruction. Instead of proposing a series of adaptations, which, while meeting the needs of some, tend to stigmatize, she decides to revolutionize classroom teaching by relying on the principles of differentiation. Her gaze quickly turns to the potential and uniqueness of each pupil’s learning profile rather than their deficits. Instead of offering a single approach with minor adjustments, she introduces a wide variety of options in her lessons: hands-on, visual activities like building models, videos, and artistic expression through drawing and coloring. Throughout the activities, she moves between the groups, offering personalized guidance and feedback. Sarah understands that students do not all learn the same way, so she allows different ways to express their understanding: some students write reports, others give verbal presentations, and some create posters or models.

Not only are the tools available multiplied, but also the opportunities for pupils to interact with the content and demonstrate what they are learning. More than anything, the teacher notices the excitement in the eyes of the pupils, who are motivated and more self-confident, less concerned about measuring up or comparing themselves with their peers. By the end of the lesson, every student has engaged with the material in a meaningful way that suited their strengths and interests. The class finally begins to appear as a learning community. Initially, the change in perspective requires a planning effort on the part of the teacher, but this is amply rewarded.”

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is differentiation, and how does it support all learners?

- Why is differentiation crucial for inclusive education?

- How can teachers implement differentiated goals to address diverse needs?

- What strategies help teachers adapt content, process, and product for all learners?

Introduction to Topic

Differentiation is a pedagogical approach to instruction that embraces the various needs of students, increases meaningful learning, and encourages motivation. It is an important practice for teachers at every level and subject area to develop consistently, because it fosters a positive learning environment, as well as, students’ self-determination and engagement in the learning process.

The term “differentiation” is frequently mentioned in international pedagogical literature, although it does not always convey the same meaning (Graham et al., 2020; Lindner & Schwab, 2020). It is often, erroneously, associated with individualisation strategies for students with disabilities and other special educational needs or to curriculum differentiation for gifted and talented students. With differentiation we, instead, refer to all classroom teaching strategies planned, taking into account the characteristics, abilities, interests, talents, experiences and needs of all students, and based on the main principles of inclusive education: respecting and valuing diversity, encouraging participation, and fostering active and meaningful learning of all students (UNESCO-IBE, 2021).

The most recognised author in the field of differentiation is Carol Ann Tomlinson, a former teacher who has developed not only a conceptual framework but also an operational model, showing its applications in all school levels, from preschool to upper secondary school, and in multiple subject areas, as well as in classroom management (e.g. Tomlinson, 2001, 2014; Tomlinson & Cunningham Eidson, 2003; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Other authors dealing with differentiation tend to refer to Tomlinson’s model to develop guidelines for teaching planning (e.g., Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Renzulli, 2015).

Tomlinson (2017) presents differentiation as a philosophy of instructional design based on two main principles: the recognition of all students’ differences and, therefore, the importance of tailoring learning for all; the acknowledgement of commonalities within the class group, needed to create a community of learning. According to Tomlinson’s model, teachers can differentiate through content, process, product, and assessment.

This approach aims to overcome both the traditional model “one size fits all” and the “micro-differentiation” strategies, which design instruction for a hypothetical average student and provide support and adjustments only for students experiencing difficulties (Tomlinson, 2001, 2017).

The application of this ‘philosophy’ of instruction requires a set of knowledge, awareness and self-reflection on the side of teachers. Tomlinson (2017) affirms that differentiation needs to be ‘proactive’ (planned in detail in advance), ‘qualitative’ (requiring a transformation of the assignment and not only its mastery levels) and ‘multiple’ (in terms of content, process and product).

Approaching this teaching model means transforming one’s set of beliefs about learning and teaching. Planning differentiated instruction for a specific class group requires multiple techniques of pre-assessment, ongoing monitoring and summative assessment. Moreover, to ensure full implementation, teachers need to consider contextual constraints and available resources. First of all, teachers need to collect information on their students, in order to define individual profiles for each and to acquire a deep knowledge of the relational dynamics of that specific class. These documents provide for each student a detailed description of their characteristics and learning profile, information which are needed to plan the most appropriate teaching strategies and to offer relevant learning contents.

Based on these profiles, teachers exercise their instructional strategies to meet all needs, experiment with them and, at the end, verify their effectiveness to constantly improve the quality of their instructional proposal.

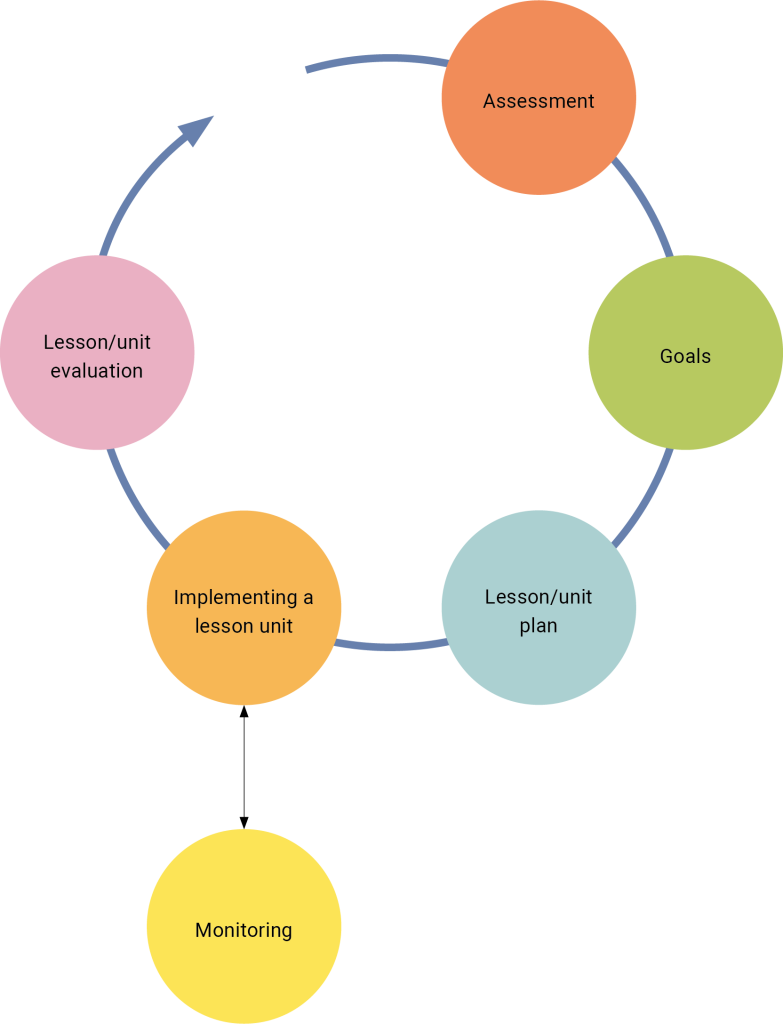

Figure 1: The cycle of differentiation (inspired by Chapman & King, 2013)

The planning cycle in differentiation therefore involves a self-reflective effort on the part of the teacher who, aware and informed of the heterogeneity of their class (interests, skills, expectations, preferences), takes this into account at every stage (planning, implementation, evaluation), and considers this data as an opportunity for monitoring and self-improvement, in order to make the proposals increasingly effective and personalised.

Why is differentiation important?

Differentiation is a perfect example of an approach that puts the principles of inclusive education into practice. This is true for two main reasons. On the one hand, it considers the globality of each student’s learning profile, encompassing not only curricular competencies but also social-emotional skills, life skills, motivation and interests. This way it ensures full accessibility of educational activities, it responds to individual needs and supports the overall development of the individual. On the other hand, differentiation tries to balance individual needs with the effort to build and maintain unity in the learning community represented by the class group or school context. Therefore, attention is also paid to social participation and the quality of relationships in the classroom(Linder et al, 2019).

Is differentiation always inclusive?

An educational proposal tailored for a specific class group, which proves to be effective and inclusive, may not be successful for another class. At the same time, some teaching proposals that may, apparently, fall under the concept of differentiation, such as ability grouping, are not necessarily consistent with the principles of inclusion and may lead in opposite directions to those initially pursued.

Planning “with all students in mind” (UNESCO-IBE, 2021, p. 17) might not be sufficient to plan inclusive teaching strategies, even when the teacher has tried to take into consideration all the information at their disposal about the students. So, every time you try to apply the principles of differentiation to your teaching proposal, question their ability to ensure not only learning but also participation and well-being for all students. It is a delicate balance between the needs of each individual student and that of the whole class, where students share meaningful learning experiences and build a community with a sense of belonging (Norwich, 1994).

How is differentiation the same or different from accommodations or modifications?

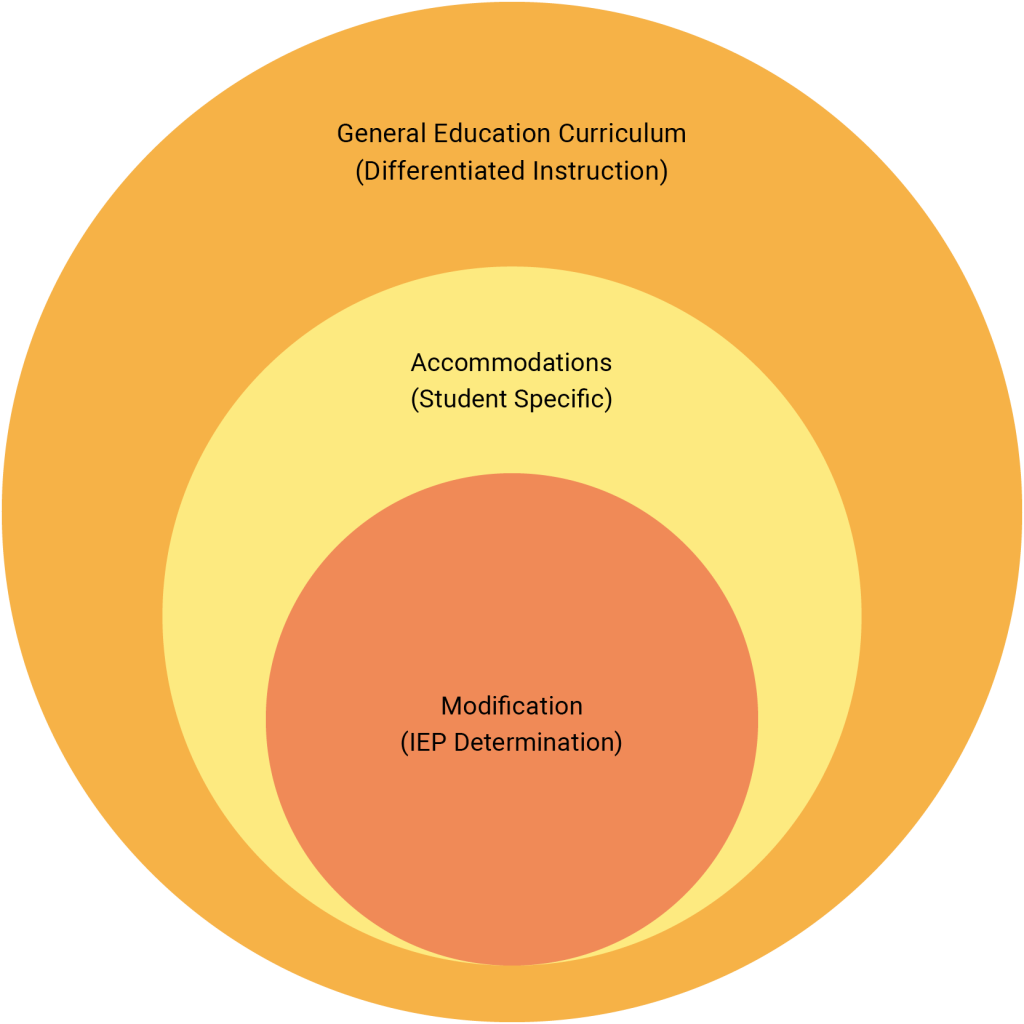

Any tailoring that is made to the general education curriculum is considered differentiation. Both adaptations and modifications fit under the umbrella term differentiation. When a student’s needs go beyond differentiation to the general curriculum, then that student, or group of students, requires specific changes to how the learning happens. Those students have moved into a more targeted kind of differentiation called accommodations (Education Service Center, 2020).

If general differentiation and specific accommodations to the learning environment do not allow the student to reach their full potential, then that student may need targeted modifications that actually alter what the student is learning. Whether it is changing the learning targets to reduce the amount of content that the student needs to know at the end of the year or teaching the student at a lower grade level, if the goals are different than the curriculum, that is considered a modification (McGlynn & Kelly, 2019).

As seen in Figure 2, differentiation, accommodations, and modifications have their place in supporting student learning. They fit together to provide the appropriate amount of support to create optimal student learning.

Figure 2: Differentiation versus accommodations or modifications

When we consider how specific accommodations and modifications fit within differentiation, it becomes clear that differentiation is essential for all students. Every learner has unique strengths and areas of potential that can be built upon, and differentiation provides the opportunity to nurture these. Students with disabilities require tailored approaches, just as neurotypical students or those working at grade level do. Similarly, all students possess areas of ‘giftedness’—whether in academics, creativity, social skills, or other domains—and these talents can flourish with differentiated learning opportunities (Seitz Pfahl, 2013). By embracing this inclusive perspective, differentiation benefits everyone, ensuring each student is challenged, supported, and engaged in meaningful ways.

How can teachers provide differentiated learning opportunities?

How can teachers approach differentiation for the first time?

Tomlinson (1999, 2001) affirms that all teachers differentiate, with different modalities and gradations. Some teachers differentiate only some aspects but do it for all students (e.g., learning contents, learning materials), others differentiate only for some students.

A good way to approach differentiation for the first time could be to ask yourself what you are already differentiating (content, processes, product) and for whom (for the whole class, some students or only for one student), and then to define what are your goals in this matter. What would you really like to improve in your teaching strategies to make them more inclusive? What are the aspects that do you perceive as most important to your class group right now? Define a short list of goals for planning according to differentiation model, such as establishing new routines in classroom management, organising learning groups or assigning learning materials. When you are clear about what you would like to accomplish, you start thinking about what information you need about your students and your classroom.

How can teachers use assessment for differentiated instruction?

According to the differentiation approach, assessment is a key element in instructional design. To plan effectively differentiated instruction, many authors suggest relying on multiple forms of assessment (Tomlinson et al., 2009; Chapman & King, 2013). Specifically, we can distinguish three main phases of assessment:

- pre-assessment or diagnostic assessment: to know students, define initial competences and needs and plan goals;

- on-going monitoring and formative assessment: to monitor students’ progresses and well-being, and to provide constant feedback;

- final (summative and/or formative) assessment: to inform students about their outcomes and to provide useful feedback on the whole unit learning experience.

Moreover, this information constitutes a significant indicator of teaching effectiveness, as they allow teachers to reflect on the appropriateness of the learning objectives and teaching strategies chosen, as well as enabling an update of the students’ profile and more careful and targeted future planning.

What data are teachers going to collect for initial multidimensional assessment?

To consider the globality of each student’s learning experience and needs, teachers need information not only on academic but also social-emotional and adaptive skills, as well as motivation and interests. Tomlinson (1999, 2001, 2014) underlines, in particular, three aspects: readiness, interests and learning preferences. Based on the principles of inclusive education, we believe that the list could be more extensive and articulate (see Table 1).

Table 1: Collecting information on your students

| Academic readiness | Knowledge (know and understand) |

|---|---|

| Skills (do) | |

| Socio-emotional competencies | Self-awareness |

| Self-management/Self-regulation | |

| Social awareness | |

| Relationship skills | |

| Responsible decision-making | |

| Social relationships in the class | Friendships |

| Collaboration | |

| Marginalisation / Bullying | |

| Attitudes towards… | School / Learning (motivation) |

| (Specific) subjects | |

| Diversity | |

| Learning profile | Preferences about learning materials (e.g., reading, listening, watching a video) |

| … about the learning environment (e.g., outdoor learning, silence/music, light, etc.) | |

| … about types of activities (e.g., verbal/linguistic, visual/spatial, bodily/kinaesthetic, musical/rhythmic, logical/mathematical) | |

| … about preferred product (e.g., oral presentation, written task) | |

| … about relations during class activities (individual/pair/group) | |

| Interests | Interests in curriculum areas |

| … related to out-of-school activities (e.g., sports, music and other free-time activities) | |

| Basic skills | E.g., using scissors, going to the bathroom, … |

| Others | Critical thinking |

| Self-determination | |

| Ambitions (e.g., further education and training, working career) |

Not all of this information is essential for all students and all situations. Each teacher decides what is relevant for that class group, for that specific context, for that specific subject. Therefore, the list could be even longer or include only a couple of elements. Teachers approaching differentiation for the first time may choose to select a few items and, as time progresses and the experience accumulates, continue to enrich the individual student records and class group descriptions.

As differentiation tries to balance individual needs with the effort to build and maintain unity in the learning community represented by the class group or school context, attention is paid to individual aspects but also to social participation and the quality of relationships in the classroom. For example, in a poorly cohesive class a teacher might give priority to social-relational aspects and attitudes, in another where there are many students who show little interest and behavioural problems, to motivation and hobbies, in another where there are multiple levels of readiness to analyse curricular knowledge and skills.

This way, on a case-by-case basis, teachers ensure full accessibility of educational activities, respond to individual needs and support the overall development of the individual.

How to collect data for initial multidimensional assessment?

Teachers have a variety of tools at their disposal to obtain this information, such as individual interviews, questionnaires or observation, and can select the most appropriate ones according to the situation and the type of information needed. For example, when working with small children, teachers may opt for observation, while when working with adolescents could prefer questionnaires. They may also decide for a certain type of instrument according to its ease of administration (e.g., time and resources constraints). Much therefore depends on the teacher’s decision, on their considerations and on their creativity. Teachers can take inspiration from tools proposed in the literature or develop their own. The same applies to the choice between instruments that are more quantitative (e.g., standardised tests) or qualitative (naturalistic observation, class discussion). To ensure reliability of information, however, we suggest combining several different instruments.

Furthermore, for qualitative instruments or for instruments aimed at understanding classroom dynamics, we suggest a comparison with colleagues, who might offer a different perspective (e.g., observation, Moreno’s sociodrama).

Table 2: Instruments for gathering information on your students

| Instrument | Examples |

|---|---|

| Standardised test | Entrance test in maths, science, English, … |

| Class/group activities | Brainstorming on initial competencies (e.g., defining a concept and making concrete examples), know/want-to-know/learned, … |

| Questionnaire | Self-evaluation of initial competencies questionnaire, questionnaire on attitudes, questionnaire on wellbeing, … |

| Playful activities | Ice breakers games, … |

| Observation | Structured observation with a grid during individual or group activities, recording critical incidents, … |

| Sociogram | Sociograms to identify popular and isolated students, clusters and/or group dynamics. |

| Self-representation | Glyphs, drawings about learning preferences or learning environment, …. |

| One-to-one meetings with the students | E.g., to discuss individual challenges and competencies, …. |

| Group discussion | E.g., about relationships and wellbeing in the classroom, about interests, … |

| … | … |

Let’s take an example. At the beginning of a new school year and cycle, such as the first year of middle school, a teacher may need to assess his or her students’ study strategies, self-regulation and collaboration skills, and motivation. The quickest and simplest way might be to administer a brief self-assessment questionnaire and, afterwards, organise a short class discussion on the students’ answers. This could be a good opportunity to identify possible strategies to support each student’s learning and motivation.

EXAMPLE 1: Self-evaluation questionnaire

| 1 (rarely) | 2 (sometimes) | 3 (often) | 4 (always) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I can ask for help if I am having difficulty | ||||

| I can handle stress and frustrations at school | ||||

| I can be self-motivated when I learn | ||||

| I can work in groups and collaborate with my peers | ||||

| I can organise myself effectively when studying alone (e.g., timing, strategies) | ||||

| I listen to and respect opinions different from my own |

Example inspired by Tomlinson, C.A., & Imbeau, M.B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. Association Supervision for Curriculum Development.

Let us take another example. Suppose that a teacher wants to organise group activities but, the first time, encounters difficulties in managing the class group. She/he could set up a semi-structured observation grid to monitor each student’s difficulties and the relational dynamics in the classroom during group activities. She/he could also ask a colleague to apply the same instrument during his/her group activities with the same class, to understand whether the problem concerns specific students, who need more support or specific adaptations, or if the challenges are due to unsuitable instruction strategies or materials. This would represent an opportunity to enhance collaboration between teachers, to share perspectives on a group class or on specific students, and to exchange ideas on classroom management and learning material design.

EXAMPLE 2: Semi-structured observation grid (author-created example)

| Group activity STUDENT: ________________ |

|||||

| 1 (rarely) | 2 (sometimes) | 3 (often) | 4 (always) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication/Interaction | |||||

| Collaboration | |||||

| Focus on task | |||||

| Self-regulation | |||||

| Autonomy | |||||

| Time management | |||||

| Activity engagement | |||||

| … | |||||

How can teachers make use of differentiated goals?

Often national or local curricula provide an orientation framework, which is then adapted to the respective context in school-internal curricula. The selection of appropriate targets should be based on the current competencies and interests of the students and the requirements of the national/local curriculum and the school’s internal curriculum. The conditions of learning recorded in the assessment play an important role in ensuring that learners are not over- or under-challenged. When students with completely different learning needs learn together, it is important to keep in mind that some of the goals might be different. At the same time, it is important to realise that the goals of students with very different starting points do not have to be different. As we will show in the section on teaching and learning strategies, changing framework conditions (support systems, time, space) can also contribute to achieving essentially the same goals.

How do the goals relate to the curriculum and class objectives?

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that some learners will not be able to achieve certain goals regardless of the support they receive. These learners will especially benefit from differentiated learning goals. Even with differentiated goals it is important to offer everything to all learners (materials of all levels) to prevent limiting them and to support them to reach their highest potential. Also, learners might jump ahead or take more time to reach essential goals.

How can goals relate to social skills?

In some countries, social, personal and action competences have been included in the curricula alongside subject-related competences (e.g., Germany, Ireland).

For inclusive education central goals, that are not subject related is to ensure children are:

- able to relate to others,

- can communicate and work together with others,

- can express their needs and

- can ask for support to reach their goals as tools to develop autonomy.

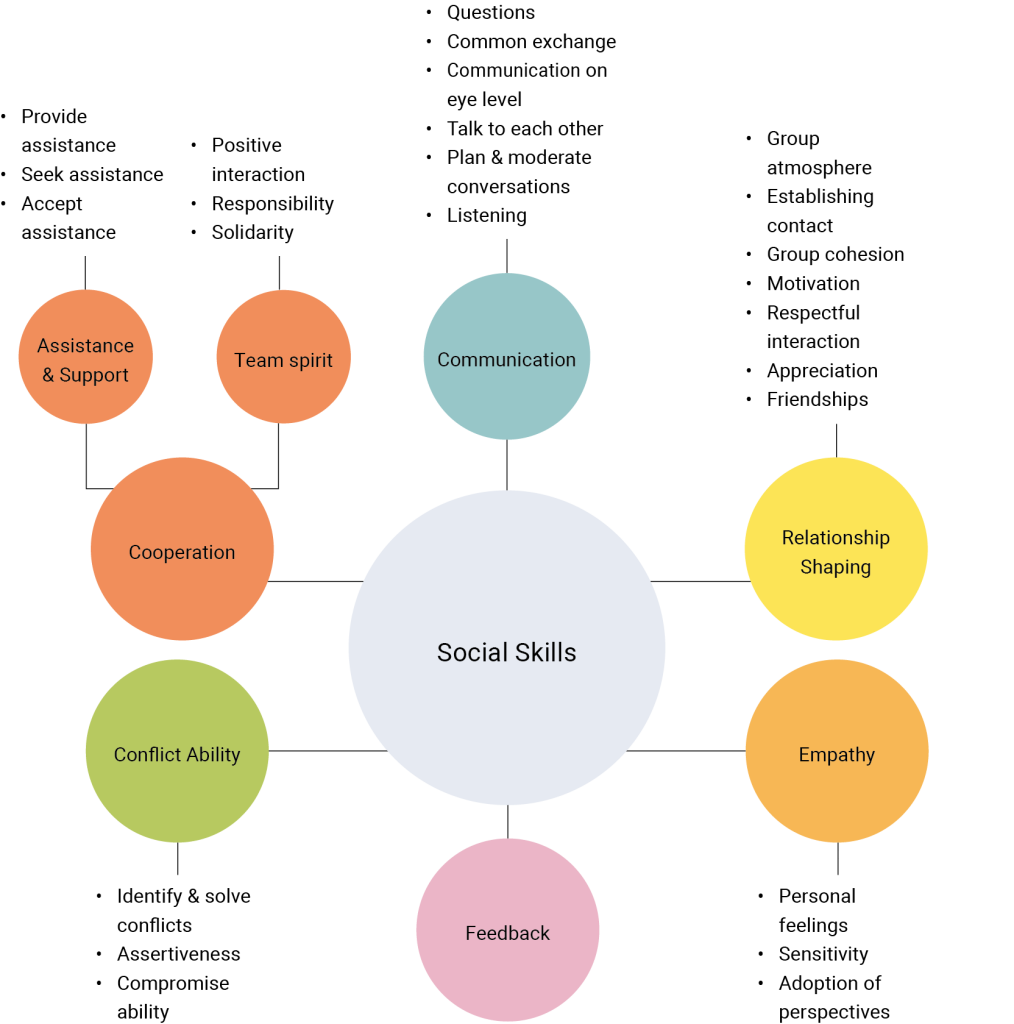

These social skills may need differentiated goals for some learners as well. The individual goals might be related to the different dimensions of social skills (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – The empirical-adapted “Dimensional Model of Social Skills – DMSS”.

The dimensions of social skills outlined in Figure 3 provide a structured framework for understanding and addressing these goals within inclusive education. For example, the ability to relate to others connects directly to the “Relationship Shaping” dimension, which includes elements like group cohesion, motivation, and respectful interaction. Effective communication and collaboration align with the “Communication” dimension, emphasizing skills such as common exchange, planning and moderating conversations, and listening. Expressing needs is supported by the “Empathy” and “Feedback” dimensions, focusing on personal feelings, sensitivity, and adopting perspectives. Finally, the ability to ask for support is encompassed within the “Cooperation” dimension, with components like providing, seeking, and accepting assistance. Differentiated goals for individual learners can draw on these dimensions to create tailored pathways for developing autonomy and fostering inclusive environments.

How can teachers include students’ perspectives (needs and interests) into the selection of goals?

Teachers can use 1:1 interviews, group feedback, and mentoring models to understand students’ perspectives. It is essential to be mindful of power dynamics within the group and between students and teachers, creating structures that enable all students to voice their thoughts freely—including the opportunity to question and critique teaching practices—without fear of negative consequences.

For students who do not communicate verbally, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools such as visual aids, communication boards, or speech-generating devices can enable expression. Observational methods are equally crucial—teachers can analyse gestures, facial expressions, and engagement during activities to understand preferences and needs.

Collaborating closely with parents and caregivers is essential, as they offer valuable insights into the child’s communication style, interests, and behaviors across different contexts. Regular exchanges of information through meetings, communication logs, or informal check-ins help build a comprehensive understanding of the student’s needs and preferences, ensuring consistency between home and school environments.

Incorporating multisensory activities and tools like eye-tracking technology can further reveal students’ choices and interests, even in the absence of spoken language. Teachers can also collaborate with parents and caregivers to leverage shared knowledge about the child’s communication style and preferences. Frameworks like the SCERTS model (Social Communication/Emotional Regulation/Transactional Support) and the Mosaic Approach provide structured ways to include diverse forms of communication, helping teachers interpret nonverbal cues and create opportunities for students to express themselves. By combining these strategies, teachers can meaningfully include all students’ voices in goal-setting and ensure their needs and interests are prioritised.

By adopting these strategies, teachers can create learning environments that are responsive to individual student needs and promote active participation in setting learning goals. This student-centered approach is reflected not only in daily classroom practices but also in broader educational models.

One example from progressive secondary schools in Germany, such as Stadtteilschule Winterhude, illustrates how structural changes can support student agency. In these schools, structured learning modules are offered for each subject in dedicated rooms (e.g., one room for Math, one for German, and one for English), allowing students to choose daily which room to attend and which subject or topic to focus on. Students set their own daily learning goals based on their interests and needs, which they document in personal logbooks. This practice encourages self-reflection and helps track progress over time.

To ensure balanced learning and prevent any subject from being overlooked, students participate in bi-weekly evaluation talks with teachers. These reflective conversations provide an opportunity to review progress, discuss challenges, and adjust goals as needed. Assessments are tied to individual modules and can be taken multiple times, emphasising the documentation of learning and understanding rather than serving as a judgment of abilities. This approach fosters a growth mindset, where learning is seen as an ongoing process rather than a one-time performance.

How can we balance the curriculum and the needs and interests of the students?

Achieving a balance between the structured curriculum and the diverse needs and interests of students is a critical aspect of differentiated instruction. This balance can be attained by adopting a flexible approach to curriculum delivery, where educators integrate student interests into the framework of the existing curriculum. Teachers can start by identifying core learning objectives and then explore creative ways to connect these objectives with students’ interests and experiences. For instance, a lesson in history could be linked to contemporary issues that resonate with students, making the subject more relevant and engaging. Additionally, incorporating a variety of instructional strategies, such as project-based learning or inquiry-based approaches, can cater to different learning styles while adhering to the curriculum standards. It is also vital to create a classroom environment that values student voice, encouraging them to express their interests and learning preferences. This ongoing dialogue helps educators to continually adapt and refine their teaching methods to suit the evolving interests of their students. Through such practices, educators can not only ensure curriculum fidelity but also create an inclusive and stimulating learning environment that motivates all students to engage deeply with their education (Schiefele, 1991).

Can the computer select the goals?

In the realm of differentiated instruction, the role of technology, particularly computers, in goal setting is a nuanced topic. While computers offer immense potential in analysing student data, providing personalised learning paths, and even suggesting learning goals, the selection of these goals should ideally remain a human-driven process. This is because computers, despite their advanced algorithms, may not fully comprehend the complexity and subtleties of individual student needs, interests, and socio-emotional factors. Teachers, on the other hand, can interpret data with a deeper understanding of the students’ context, backgrounds, and classroom dynamics.

Additionally, the process of goal-setting should actively involve students, empowering them to take ownership of their learning. When students collaborate with teachers in defining their goals, it fosters self-regulation, motivation, and a deeper connection to their educational journey.

It is also critical to consider the ethical implications and potential biases in algorithms. Decisions based solely on computational suggestions could unintentionally reinforce inequities or overlook the diversity in classrooms. Teachers, therefore, play a vital role in ensuring that the ethical dimensions of goal-setting are addressed, aligning technological inputs with inclusive, equitable practices.

The fluid nature of classroom environments and the broader contexts of students’ lives—such as their emotional states, cultural backgrounds, or personal experiences—further underscore the limitations of technology in this area. Computers, despite their precision, cannot fully account for the dynamic and multidimensional aspects of human development.

As technology continues to evolve, teachers’ roles may shift, requiring them to act as critical facilitators who assess and adapt technological recommendations to align with the holistic needs of their students. Preparing teachers for this evolving role through professional development and equipping students with the digital literacy necessary to critically engage with AI tools is essential to maintaining a balanced and future-ready approach.

Even in times of multimodal AI and the rise of multimodal robotics, the selection of goals should remain in the hands of students and teachers. This ensures that while benefiting from technological advancements, educational goals stay rooted in a holistic understanding of student development, encompassing academic, social, and emotional learning needs.

How can teachers differentiate content in their classrooms?

Content is what students need to know, understand and be able to do as a result of a section of study (IRIS Center, 2022; Tomlinson, 2001). That is, it is the “stuff” we teach and want students to learn (Tomlinson & Cunningham Eidson, 2003). National, state, and local standards for teaching content provide teachers with guidance on what they should teach. However, a set of standards is unlikely to provide complete and consistent content. The content is therefore defined also by local curriculum guides and textbooks. Content is typically derived from a combination of sources. However, one of the most critical factors in determining the content is the teacher’s knowledge of both content and students (Tomlinson & Cunningham Eidson, 2003).

Content knowledge refers to the body of knowledge (facts, theories, principles, ideas, vocabulary) that teachers must master to be effective (UNESCO, 2022). Although effective teaching relies heavily on a deep understanding of the subject matter, mastering this alone is insufficient. Shulman (1986) emphasises that teaching requires not only knowledge of the facts and concepts but also a comprehensive grasp of how the subject fits into its broader discipline and curriculum (UNESCO, 2022). In addition, he also states that teachers need to understand why a particular subject is particularly central to one discipline, while another may be somewhat secondary (Shulman, 1986).

According to Shulman (1986), in addition to content knowledge and curriculum knowledge, teachers need pedagogical content knowledge. “Pedagogical content knowledge is a type of knowledge specific to teachers and is based on the ways in which teachers relate their pedagogical knowledge (what they know about teaching) to their subject knowledge (what they know about what they teach). It is the integration or synthesis of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and subject matter knowledge that constitutes pedagogical content knowledge” (p. 14). Pedagogical content knowledge enables teachers to “know how to organise and present content in ways that make it accessible to increasingly diverse groups of learners” (Shulman, 1987, as cited in Cooper & Alvarado, 2006, p. 5; UNESCO, 2022). The link between content and pedagogical knowledge determines teachers’ decisions about materials, teaching approaches, assessment of students’ learning, and feedback, among others (Cooper & Alvarado, 2006; Bold et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2022). In this context, pedagogical content knowledge is “a conceptual map of how to teach a subject” (Villegas-Reimers, 2003, p. 39).

Another critical factor in determining the content is teachers’ knowledge of their students. Content can be differentiated in response to the student’s readiness level, interests, or learning profile, as well as in response to any combination of readiness, interest, and learning profile (Tomlinson, 2001). Because students’ readiness, interest, and learning profiles vary, it is important to diversify or differentiate content in response to these students.

Building upon these foundational concepts, the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework extends Shulman’s idea of pedagogical content knowledge by incorporating technological knowledge (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). The TPACK framework highlights the dynamic interplay between content, pedagogy, and technology, emphasising that effective teaching requires not just expertise in these areas individually, but an integrated understanding of how they interact to enhance student learning.

Technology plays a pivotal role in differentiation by providing diverse and adaptable tools that meet the varying needs of students. Digital tools such as interactive simulations, educational software, and learning management systems allow teachers to present content in multiple formats, catering to different learning styles and preferences (Koehler, Mishra, & Cain, 2013). Additionally, technology enables the creation of adaptive learning environments where content can be personalized based on students’ readiness levels and progress, offering both remediation and enrichment opportunities as needed (Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005).

Moreover, technology facilitates differentiated assessment practices, providing immediate feedback and data-driven insights into student learning. Formative assessment tools, such as online quizzes and e-portfolios, allow for real-time monitoring of student progress, enabling teachers to adjust instruction accordingly (Puentedura, 2013). This continuous feedback loop supports a more responsive and inclusive approach to teaching, ensuring that all students receive the support they need to succeed.

In summary, the integration of technology within the TPACK framework is essential for implementing differentiated instruction effectively. By leveraging technological tools in conjunction with strong content and pedagogical knowledge, teachers can create flexible, engaging, and inclusive learning environments that address the diverse needs of their students.

How do teachers differentiate content according to student readiness?

Readiness refers to a student’s level of knowledge and skill regarding the given content and is a student’s proximity to learning goals at a given time (Tomlinson, 2014); it is the place where the student is according to where the learning objectives say the student should be (Hockett, 2018). Students’ readiness levels can be affected by their background knowledge, life experiences, or prior learning about a course or content, and their readiness levels may also vary according to courses or content areas. Student readiness is not a fixed factor. Sometimes a student who has a marked difficulty in learning one subject may have a surprisingly large amount of background knowledge on another subject. In this case, the student may be ready for more advanced studies than is usually expected. On the other hand, students who are usually quite advanced may miss some prerequisites in a subject or be distracted by other subjects in their life. In this case, they may need more solid experience to be successful. For this reason, teachers should use various assessment methods in order to determine the readiness level of students for any content and differentiate the content according to student needs based on the assessment data they have obtained.

How do teachers differentiate content according to student interests?

Another student characteristic considered in differentiated instruction is interest. Interest is what the student enjoys learning, thinking and doing and is a great source of motivation. Students’ interests are topics and/or processes that arouse curiosity and inspire passion (Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2009; Tomlinson, 2005a, 2005b). The purpose of interest differentiation is to help students connect with new knowledge, understanding, and skills by promoting intrinsic motivation by uncovering connections to what they already find attractive, intriguing, relevant, and valuable (Tomlinson, 2003). Differentiation by interest means creating instruction based on the interests students bring to the classroom, or offering students options within an instructional stack that they want to dive deeper into (Tomlinson, 2001) and this allows educators to connect students and engage them in a lesson (Tomlinson, 2001, 2003).

For example, environmental pollution, global warming, recycling, etc., which constitute a unit related to the environment. The student’s choice of topics will reveal the student’s interest in any of these topics.

How do teachers differentiate according to learner profiles?

The learning profile, on the other hand, refers to the wide variety of ways in which students differ in how they prefer to deal with the content, process, and product, according to Tomlinson (2003). A student’s learning profile is a complete picture of their learning preferences, strengths, and challenges. According to Tomlinson and Imbeau (2010), a student’s learning profile is shaped by four elements and the interactions among them: learning style (a preferred contextual approach to learning), intelligence preference (a hard-wired or neurologically shaped preference for learning or thinking), gender (approaches to learning that may be shaped genetically or socially for males versus females) and culture (approaches to learning that may be strongly shaped by the context in which an individual lives and by the unique ways in which people in that context make sense of and live their lives). The purpose of differentiation by learning profile is to help students learn in the ways they learn best and to expand the ways in which they can learn effectively. Because students are more productive in their learning when they are allowed to work in ways that are comfortable for them.

The three basic characteristics of students, briefly described above, are critical in differentiating the content. Strategies such as tiered content, learning contracts, compacting, providing a variety of materials, presentation styles, scaffolding are used to differentiate content (IRIS Center, 2022).

What kind of strategies could teachers use to differentiate content?

Tiered Content

The strategy of tiering content is based on students’ readiness levels. The purpose of differentiating content according to readiness levels is to match the material or information students are asked to learn with their reading and comprehension capacity. Tiering content according to student readiness levels encourages students to start learning from where they are at the moment and allows students to work on challenging tasks in a way that suits them. When teachers differentiate content, all students complete the same type of activity (e.g., worksheet, report) (IRIS Center, 2022), but the difficulty or complexity of the content varies.

A task matched to student readiness takes the student’s knowledge, understanding and skills slightly beyond what the student can do independently. A good readiness match pushes the learner slightly outside their comfort zone and then provides support in bridging the gap between the known and the unknown. Tomlinson and Cunningham Eidson (2003, p. 30) provide examples of small group experiments based on preparation and interest as follows.

Divide students into groups of three or four and give each group the instructions for its assigned experiment. There are seven experiments in all, designed at varying levels of complexity and listed here from most complex to least complex:

- Experiment A: How can we determine relative humidity? (version 1)

- Experiment B: How can we determine relative humidity? (version 2)

- Experiment C: How can we determine the direction of the wind?

- Experiment D: How does air move?

- Experiment E: Does air have weight?

- Experiment F: Does air take up space?

- Experiment G: Does air have movement?

Each group carries out its experiment based on the question. Students are provided with a recording sheet as a place to collect their data as they work towards answering their questions, which has different levels of scaffolding. For students who need more support they have more specific steps or sub-steps versus students who are ready for a greater challenge who have just questions and space for documentation on their worksheet. They record all of the information required to sufficiently answer their science question. The ways that students can record their knowledge may also differ depending on how comfortable they are with scientific measurements and quantities or if they are explaining themselves using more common words. Lastly, students create a plan for how they will share their work with the rest of the class including the methods that they used and what they found in their research. Ultimately, the class will want to know if they answer their questions and what proof they have. Each group will have the opportunity to share their work and their experience based on the level of learning that they accomplished.

Differentiation Through Open and Closed Tasks

Differentiation through open and closed tasks is an effective instructional approach (Tomlinson, 2021, 48) across subject areas, including mathematics, sciences, and humanities, that caters to diverse student needs and abilities. This method involves using both structured (closed) and flexible (open) activities to engage students at various levels of understanding and skill. By blending the strengths of both types of tasks, teachers create inclusive classrooms that value student diversity and provide multiple entry points into learning.

Closed Tasks

Closed tasks are structured with predetermined outcomes and clear instructions. They are particularly effective for assessing foundational knowledge and skills, benefiting students who thrive on structure and need concrete guidance (Tomlinson, 2021, 48). These tasks are widely applicable across disciplines.

Examples in mathematics include:

- Multiple-choice questions (e.g., “What is the sum of 15 and 9?”)

- Fill-in-the-blank exercises (e.g., “Solve for x: x + 7 = 12.”)

- Step-by-step math problems (e.g., “Simplify: 2(3x + 4) – 5.”)

Examples in other subjects include:

- Labeling tasks in science (e.g., labeling given parts of a plant or an ecosystem).

- Identifying elements of a story in English literature (e.g., “Identify the protagonist and setting in the story.”)

- Timeline tasks in history (e.g., “Place these historical events in chronological order.”)

Open Tasks

Open tasks, in contrast, allow for multiple solutions and approaches. They encourage creativity, higher-order thinking, and problem-solving (Bahar & Maker, 2015), making them particularly effective for fostering deeper engagement (Hertzog, 1998). Open tasks also provide opportunities for students to showcase their unique abilities and strengths, making them a powerful tool for differentiation in inclusive classrooms. Unlike closed tasks, open tasks do not require the creation of separate materials for different levels of readiness; instead, they can be used by all students, allowing them to engage with the task at their own level and in their own way (Zohrabi & Hassanpour, 2020).

Examples in mathematics include:

- Finding multiple fraction pairs that add up to 7/8.

- Constructing rectangles with a given perimeter using various dimensions.

- Creating word problems using a specific fraction but allowing for different correct answers. (e.g. Create a story problem where 3/4 of something equals a number you choose. Solve for the total.)

Examples in other subjects include:

- Designing a poster for a historical event, including important figures and outcomes.

- Writing a diary entry from the perspective of a character in a novel or a historical figure.

- Creating a piece of artwork inspired by a theme discussed in class, such as “community” or “change.”

- Developing a science experiment to explore how light travels through different materials.

To help students orient themselves and succeed with open tasks, teachers can provide examples of possible approaches, offering inspiration while leaving space for individual creativity (Tomlinson, 2021, 48).

Medium-Open Tasks for Balance

Medium-open tasks provide a balance between open and closed tasks, offering enough structure to guide students while still allowing for creative expression. These tasks are particularly effective for scaffolding students into more open-ended problem-solving.

Examples include:

- Drawing (of) an ecosystem and labeling all the parts the student knows (without blanks).

- Creating a timeline with optional categories for additional historical events.

- In mathematics:

- Turning a closed question into an open one:

- Closed: What is half of 20?

- Open: 10 is a fraction of a number. What could the fraction and the number be?

- Removing constraints:

- Closed: There are 12 apples on the table and some in a basket. In all, there are 50 apples. How many apples are in the basket?

- Open: There are some apples on the table and some in a basket. In all, there are 50 apples. How many apples might be on the table?

- Using adaptive tasks:

- These tasks contain multiple starting points and solutions for students of different levels, allowing every student to participate and be challenged appropriately . For example: “Here you have 24 wooden cubes. Which cuboids can you build with them? Make a note of the ones you have already found. How many can you find?” (Leuders & Prediger, 2016 in Bardy et al., 2021, 33)

- Turning a closed question into an open one:

Benefits of Open Tasks

Open tasks are a versatile and effective strategy for differentiation.

They:

- Accommodate mixed abilities by allowing students to engage at their own level.

- Empower students to make decisions and develop their own thinking processes.

- Encourage students to make connections, generalise ideas, and justify their reasoning.

- Provide opportunities for creativity and self-expression across a variety of subject areas.

Balancing Open and Closed Tasks for Differentiation

Using a combination of open and closed tasks enables teachers to:

- Cater to diverse needs: Closed tasks ensure foundational skills are addressed, while open tasks encourage creativity and exploration.

- Support different learning profiles: Students who thrive on structure benefit from closed tasks, while those who enjoy autonomy excel in open tasks.

- Encourage inclusive participation: By providing both types of tasks, all students can engage meaningfully and demonstrate understanding.

By combining these approaches, teachers foster an inclusive learning environment that values both structure and flexibility. This ensures all students can engage meaningfully, build confidence, and express their strengths in unique ways.

Differentiation matrix

The differentiation matrix developed by Ada Sasse (2014) offers a structured tool to design lessons that address the heterogeneity of a learning group. This matrix enables educators to balance cognitive and thematic complexity in their lesson planning, fostering inclusive learning environments where students with varying levels of ability can work collaboratively on the same topic.

Figure 4: Differentiation matrix for the “Europe” lesson plan for a mixed-age class with grades 1 to 4

| Abstract operations | – Mountains – Places of interest |

– Capitals of neighbouring countries – Flags |

– Greek yoghurt – French cheese – Italian pasta – Dutch cheese |

– Famous Italians, footballers | – Famous Frenchmen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic operations | – Map work: Berlin, Thuringia | – Location of the capital and flag | – Meaning of the word European Union | Presentation | Presentation |

| Fully imaginative action | – Saale, Jena – Rivers, lakes, seas, transport routes |

– Assignment of certain countries to individual colours (material) | – Buy goods from other countries with different money, export different goods from other countries | – Capital city: Places of interest | – Capital city, sights |

| Partial imaginative action | – Federal states on a map Thuringia and its neighbouring countries | – Assignment of countries via colours and plot | – European puzzle, assignment via colours | – Prepare something from Italy, Count to 10 in Italian | – Prepare something from France, Count to 10 in French |

| Practical and illustrative action | – Jena in Germany – Germany puzzle; capital city |

– Germany puzzle and its neighbouring countries | – Money from the EU, Differences commonality (play money) | – Food from Italy – Italian vocabulary |

– Food from France, French vocabulary |

| Germany | Neighbouring countries | Europe | Presentation topic | Country 2 |

by Sabine Lada and colleagues at the Maria Montessori State Community School in Jena (Sasse 2014)

For instance, the “Europe” matrix used at the Maria Montessori State Community School in Jena illustrates how teachers can tailor activities to different cognitive levels while maintaining thematic unity. Practical actions, such as recreating Italian dishes or building puzzles of Germany’s neighbors, are paired with more abstract operations, like analyzing famous figures or creating presentations on capitals and flags. This layered approach allows students to engage with content at a level appropriate to their skills while exploring the same overarching theme. By enabling collaborative planning among teachers and emphasizing student agency—students select tasks aligned with their interests and abilities—the matrix ensures both individual and social connectivity. This dual focus supports inclusive education by providing equitable access to meaningful learning experiences across diverse student profiles.

Learning Contracts

“A learning contract is a written agreement between teacher and learner that outlines mutually agreed upon goals, tasks, and expectations” (adapted from Greenwood, 2003, p. 1). These contracts are inherently collaborative, involving both parties in a negotiation process that respects the student’s voice and learning preferences. While the teacher brings expertise in curriculum and pedagogy, the student contributes vital insights into their own learning style, interests, and goals. In a well-structured learning contract, both the teacher and student make commitments. The student typically agrees to complete specific tasks, meet certain quality standards, and adhere to agreed-upon timelines. The teacher, in turn, might commit to providing necessary resources, offering regular feedback, or adapting instructional methods to suit the student’s learning profile. Contracts can contain both skill and content components and are well suited to a differentiated classroom as the components and terms of the contract can vary according to the student’s needs (Tomlinson, 2017). Through this process, teachers can differentiate the curriculum based on student readiness or learning profiles, while students gain agency in their learning journey (IRIS Center, 2022). During the negotiation process, both parties collaboratively determine:

- The tasks to be completed

- The timeline for completion

- The quantity and quality expectations of the work

- The evaluation criteria

- The support and resources the teacher will provide

This mutual approach not only motivates students who may have difficulty accomplishing academic tasks but also empowers them by giving them a voice in their education. By jointly committing to specific, positive study and learning behaviors, both teachers and students create a more engaging and personalized learning experience (Frank & Scharff, 2013).

Compacting

Teachers can differentiate instruction by compressing the curriculum for advanced students who already master certain content or skills. Curriculum compacting is a technique for differentiating instruction that allows teachers to make adjustments to curriculum for students who have already mastered the material to be learned, replacing content students know with new content, enrichment options, or other activities (NAGC, 2022; Renzulli & Reis, 2014). Curriculum compacting allows students to skip content they know or to proceed quickly through content. This strategy targets students’ readiness levels and it can be applied to any subject and at any grade level (IRIS Center, 2022).

How do teachers use differentiated teaching strategies in their classrooms?

What does differentiation look like in the classroom?

How differentiation looks in the classroom depends on the age group and profiles of the students, the content area, and the unit of study. As there is an endless variety of possibilities, we know that no two differentiated classrooms look the same, though we can see common strategies and practices. The following strategies are some possibilities to look for in the learning process of a differentiated classroom.

Proactive

Instructional strategies in the differentiated classroom are, first and foremost, proactive. They are carefully designed in advance based on assessments data, student feedback, and class or student goals. Seen in the previous sections, the importance of collecting data and formatting goals is critical to ensuring objectives are clear and appropriate strategies are chosen (Carolan & Guinn, 2007). The next step is to verify what content pieces are being taught and choose the strategies by which students will interact with the information.Using a clear and concise planning template helps to see the connections between assessment, goals (based on student assessment data), and curriculum.

Figure 5: Example of a Differentiated Lesson Plan(self-created)

| Teacher Name: | Class/Subject: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiated Lesson Plan | ||||||||

| 1. Standard/Concept/Unit/Topic/Subject: | 2. As a result of this less/unit, students will Know (facts, vocabulary), Understand (concepts), and/or Be able to DO (skills): | |||||||

| 3. Pre-assessment: | ||||||||

| 4. Grouping Decisions and Choices: | ||||||||

| 5. Learning Experiences | Instructional Resources | Content | Process | Product | ||||

| Exceeds Standard | ||||||||

| At Standard | ||||||||

| Approaching Standard | ||||||||

| 6. Post-assessment: | ||||||||

| 7. Notes/Reflection for future reference: | ||||||||

Flexible Groupings

As shared in the content related section, groups play an important role in a differentiated classroom. There are opportunities for whole group instruction around concepts, important vocabulary, or at the introduction to a topic, but the majority of the time students are working in other groupings – small groups, pairs, individually, or another combination. The classroom allows for opportunities for the group to come back together as a whole class to address questions or clarify instructions before breaking back into other groupings again (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011; Wormeli, 2007). The differentiated classroom is one in which students are rarely all working whole-group settings.

Example 3

In this example, the teacher uses different groupings to meet the needs of her students and is able to support them to work on critical thinking towards their unit of student. There may be more physical movement than a traditional, didactic classroom and the volume of noise produced by students busily working on an engaging project might be greater, but a differentiated classroom is meeting its students’ needs.

Inclusive classrooms use these groupings to encourage peer interaction and promote social integration, enabling students with diverse abilities to work together and learn from one another.

Time & Space

Flexibility also allows for changes to framework conditions like support systems, amount of time spent, or use of space which also contributes to achieving essentially the same goals. Allowing a group of students longer time to finish their work or providing multiple physical spaces for students to do independent work or have multiple check in points with one student are ways to create opportunities for flexibility throughout the school day (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011).

Opportunities to differentiate through space can be about where groups work and how students have access to materials, but it is also about the feeling of being in the classroom space. Do students feel welcomed and comfortable in the space? Are there places for calm relaxation versus more active group work? Are there places that students are invited to explore independently? How does the space invite the students to participate in their learning? Flexible learning spaces are ones that reflect the student population that use them regularly (Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014).

Another chance to show flexibility is how we allocate time in our classrooms. Following a consistent routine with a structured schedule is an important part of managing a classroom. When we look at our schedules, we can see where our priorities lie as those are the activities that we have allocated the most time or in some cases the most opportune times slots. We know that students are more ready to learn in the earlier part of the school day versus the later part, so how do we structure our time accordingly?

Presentation Styles

Students’ learning profiles are taken into account in the presentation of any content. The term learning profile refers to a student’s preferred learning mode, which can be influenced by a number of factors such as learning style, intelligence preference, gender and culture. The learning profile is shaped by these four elements and the interactions between them (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Students’ learning profile includes learning preferences (for example, is the student a visual, auditory, tactile or kinaesthetic learner?), grouping preferences (for example, does the student work best individually, with a partner or in a large group?) and environmental preferences (for example, does the student need lots of space or a quiet area to work?).

Students learn better when students’ learning profiles match teachers’ presentation styles. Therefore, teachers need to consider students’ learning profiles when presenting any content. Various methods such as narration, discussion, asking questions, reading aloud, verbal explanation, picture/graphic, transparency, whiteboard, headings, thinking aloud, taking action, creating/constructing, using manipulatives can be used in content presentation. While presenting teachers’ lessons, multimedia and formats also allow students to develop a deeper understanding of concepts by providing opportunities to interact with these concepts in a variety of ways (IRIS Center, 2022).

Materials

The choices of materials are as varied as there are projects in the classroom. As a teacher develops or collects materials for student learning, there are classic examples, such as texts or workbooks. Shared ideas will become catchier when teachers use materials suitable for the students that can attract the attention of the students in their lessons. Thus, sound (for example, the voices of others, sounds that make a term or concept clearer, music), pictures, stories, charts or figures, models, photographs, works of art, body language, movement, and other things that engage the senses and engage the mind. Elements should be integrated with the content (Tomlinson, 2001). When we work to differentiate our classroom for learners, we are looking for opportunities to create a varied collection of materials for our students to engage with over specific topics. We can expand our classrooms to include magazines, newspapers, posters, and advertisements in our literacy work. We can think about access to IT tools, emails, web-based searches, and online libraries. We can expand our thinking further to bring content area materials to our students through videos, zoom interviews, and virtual field trips. We want to ask ourselves, in how many different media can I get my student access to this information? Using multiple texts and combining them with a wide variety of other supplementary materials increases all students’ chances of accessing content that is meaningful to them. Such differentiation allows students to access information in the way that suits them best. The point to be considered here is to match the complexity, abstraction, depth, breadth and similar levels of the source materials used with the learning needs of the student.

Teachers can build in materials that support students without having to ask the teacher directly.

Example 4

Building these opportunities into the classroom is a win-win situation. The teacher benefits from the students working independently and the students benefit from being in control of their work. Differentiating materials also requires teachers to consider access to materials (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011). Who might struggle with this material and what are the ways that I can facilitate better access through that struggle? A language learner might need more vocabulary reminders with a text than a dominant language student. A student with specific learning needs might need a text-to-speech option or an audio recording to enhance their reading comprehension.

When teachers include varied resources like videos, tactile models, or interactive digital tools, they increase the likelihood that all students can engage with the content in ways that resonate with them. This variety reflects a commitment to honoring diverse learning needs and experiences.

Choice

One way to ensure that students are highly engaged in their learning is through allowing choice. When students are given options, either structured by the teacher or freely chosen by the students, they are given multiple means through which to process and show their learning (Carolan & Guinn, 2007). For example, students are allowed to choose a final project instead of taking a written exam. They are given the options of giving a presentation, performing an original piece, or writing a story.

Choices that take into account students’ interest inherently push student thinking towards engagement as it makes the learning feel more relevant. To create authentic experiences in the classroom, and therefore make learning meaningful, we need to consider why students have to know this information and the ways that they may have already engaged with this knowledge in the past.

Scaffolding

Scaffolding refers to the process by which the teacher provides additional support to enhance learning and assist in mastery of tasks for students struggling to learn a new skill or content. It is a basic support to “enable children to independently perform tasks that they could only perform with the help or guidance of the teacher” (Gibbons, 2002, p. vii). Scaffolds facilitate the learner’s ability to build on prior knowledge and internalise new knowledge. An important aspect of the scaffolding strategy is that scaffolds are temporary. As the learner’s abilities increase, the scaffolding provided by the more knowledgeable is gradually withdrawn. As children’s skills develop with support, scaffolding decreases and children are eventually able to perform on their own (Bıkmaz et al., 2010; Chang, Sung, & Chen, 2002).

The scaffold teaching strategy is often used to focus more on the learning needs of an individual student during the completion of a teaching lesson or specific task rather than on a group of students, so differentiation and core teaching strategies can be used simultaneously to better meet students’ individual teaching needs (Ray, 2022).Many different facilitative tools can be utilised in scaffolding student learning. Among them are: breaking the task into smaller, more manageable parts; using ‘think aloud, or verbalising thinking processes when completing a task; cooperative learning, which promotes teamwork and dialogue among peers; concrete prompts, questioning; coaching; cue cards or modelling. (Elandeef & Hamdan, 2021). Scaffolding is “a supportive instructional structure that teachers use to provide the appropriate mechanisms for a student to complete a task that is beyond their unassisted abilities” (Lipscomb, Swanson & West, 2010, p. 19).

For example, for a student who has difficulty multiplying two-digit numbers, after the teacher has done a task analysis, he can divide the task into manageable steps and model each step in the task, giving the student time to practise. Support is gradually removed as the student masters the task.

Another example of scaffolding can be seen when teachers use questioning to guide students’ work. Based on the students’ skill levels, the teacher can develop lines of questioning that challenge students appropriately.

Example 5

Product

If we have clearly differentiated the process of learning and yet require all the students to take the same test to demonstrate their knowledge then we are not following our obligation to support all our students. To differentiate the final product of a unit of study, we need to ask ourselves how can students show their learning? What formats are required for students to demonstrate their learning? What choices are there? How often is it done? Is it always done individually or in a group? What are the ways that you will measure students’ success (Carolan & Guinn, 2007)?

For example, a teacher can offer students a choice board of options she/he has pre-selected to match the students’ learning profiles and complete a final project. Another teacher can pose four questions and ask students to answer them in four different ways based on their own choice.

Figure 5: Tools and strategies for designing inclusive differentiated classrooms for diverse learners

| Climate | Knowing the Learner | Assessing the Learner | Adjustable Assignments | Instructional Strategies | Curriculum Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Gregory & Chapmann (2013)

As you can see in Figure 5, there are a wide range of ways to differentiate teaching instruction and make use of strategies to ensure that students are working at their readiness level. The selections in this chapter are a few of many different ways to use differentiation in the classroom. There are other models, such as inquiry-based models, that lend themselves to differentiate because of how they incorporate students’ knowledge and allow for different points of entry into learning. Exploring more about inquiry models, authentic learning, and project based/problem-based learning are other avenues for developing differentiation practices in your classroom.

How do teachers determine what strategies to use?

Teachers determine which strategies to use based on their student data – completed assessments, either formal or informal, that demonstrate students’ feedback. Having already collected this information and determined the appropriate student goals, teachers are familiar with their learners’ profiles and readiness. Therefore, they select strategies that offer the best opportunity for students to reach success.The access to materials, support, and a varied experience in the process of learning are also important determinants in choosing strategies. Strategies should be chosen to enhance access to the process as well as the product by which the students demonstrate their learning.

Finally, teachers determine useful strategies for their group through trial and error. We can find the best selection of strategies for students on a given day by approaching the process of differentiation through the constant collection of feedback (Renzulli, 2015).

How can teachers monitor learning progress?

Generally, teachers tend to design whole units of learning and check learning progress at the end of the whole course. Differentiation, however, requires activating monitoring procedures throughout the unit as well. Since activities are highly personalised, according to students’ learning preferences, interests, readiness and needs, teachers need to collect data about each student’s learning path. Normally, these monitoring activities are incorporated into the design of learning activities. For example, when teachers structure different learning materials regarding the same content. Teachers can let students choose or they can assign tasks but, in both cases, they need to monitor whether the type of activity completed by the student is adequate.

EXAMPLE 6: Activity options

| Lesson about: ________________ |

|---|

| Structured learning materials and supports ☑ Multiple options regarding the type of task/activity ☑ Multiple options for support ☑ Multiple options in terms of additional learning materials Options are structured according to ☑ Mastery level ☑ Learning preferences ☑ Interests Options are ☑ Assigned by the teacher ☑ Chosen by the student |

Example inspired by Gregory, G.H., & Chapman, C. (2013). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: one size doesn’t fit all (3rd ed.). Corwin.

EXAMPLE 7: Activity options

| Listening | Reading | Writing | Speaking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listen to a song and summarise the content of the lyrics. | Read a short narrative text and identify key words. | Write a dialogue between two characters. | Play a scene from a film. |

Example inspired by Tomlinson, C.A., & Imbeau, M.B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. Alexandria, VA, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

EXAMPLE 8: Activity options

| Verbal/ Linguistic | Visual/ Spatial | Bodily/ Kinaesthetic | Musical/ Rhythmic | Logical/ Mathematical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Make a presentation. Write a text. |

Draw a comic. Paint an illustration. |

Simulate an experiment. Organise a role-play game. |

Record a song. Invent a choreography. |

Create a diagram. Write down the sequences of an experiment procedure. |

Example inspired by Gregory, G.H., & Chapman, C. (2013). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: one size doesn’t fit all (3rd ed.). Corwin.

Similarly to the planning phase, teachers can opt for multiple instruments to collect information on the adequacy and effectiveness of learning tasks. For example, they can make observations, administer self-assessment questionnaires or organise brief class discussions at the end of the activities to obtain some feedback.

Here there are two examples of possible instruments to monitor individual learning.

EXAMPLE 9: Self-evaluation questionnaire

| Individual task STUDENT: ________________ |

1 Strongly disagree |

2 Disagree |

3 Agree |

4 Strongly agree |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The task was challenging for me | |||||

| I was able to focus during the activity | |||||

| I was not motivated during the task | |||||

| The time assigned to complete this activity was enough for me | |||||

| … |

EXAMPLE 10: Monitoring mastery

| What I have learned STUDENT __________ |

1 I am beginning to understand |

2 I could use more practice |

3 I need some help |

4 I can do it alone |

5 I know it so well, I could explain it to anyone. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designing a PowerPoint presentation | |||||

| Writing a summary | |||||

| Creating a flow chart | |||||

| … |

Examples inspired by Gregory, G.H., & Chapman, C. (2013). Differentiated Instructional Strategies: one size doesn’t fit all (3rd ed.). Corwin.

How can teachers evaluate the effectiveness of teaching practices?

At the end of the learning unit, the teacher collects, within the student profiles, the materials gathered throughout the lessons on students’ progress, difficulties and preferences. Again, as it would usually happen, they may administer a common final test. Or, even for the final summative assessment they may foresee differentiated products, allowing students to demonstrate what they have learned according to their preferences.

It is important to point out that the differentiation model does not impose minimum levels of differentiation or specific types of differentiation. It only offers guidance on how to design. Teachers can choose which ones to implement and to what extent, depending on their skills, experience and preferences, and also depending on the specific situation of the class they are working with. What is critical for an effective deployment of the model is to maintain, throughout the whole process, a strong link between instructional design and the procedures of assessment, monitoring and evaluation. Lastly, differentiation requires an aptitude for professional self-training. Each implemented unit is one more building block toward more effective future unit planning.

Conclusion

This chapter has examples of some of the ways to strengthen your differentiation practices in the classroom. At times it might feel overwhelming to consider all the elements at play in a differentiated classroom, but remember to start at the beginning of the ‘differentiation circle’. Always begin first with collecting information on the needs and interests of students. Use that information to plan goals accordingly. There will not necessarily be the same goals for everyone. That information will inform how to differentiate the content and the materials. Finally, evaluating the practices and strategies used is always the appropriate way to complete a session, activity, or project.

As this system is used, there will be more and more ease and confidence with applying differentiated strategies in the classroom. Note that not all forms of differentiation are helpful for inclusive education. There are ways that differentiation can be used which actually limit students in their learning. For example, by using Artificial Intelligence (AI) based computer programming to challenge students without an opportunity to consider the knowledge in other ways, or when students are continually offering the same strategies over time without an opportunity to assess and reevaluate student needs.

A final point to know about differentiation is that it is constantly changing. As students learn and change, a teacher needs to be adapting to those changes. There is not a perfect material or strategy that you can use effectively forever. There is not a final point of arriving at “doing” differentiation. It is an ever-evolving, a way of thinking, a framework that shifts and moves as students do. Be prepared to move with them.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.