Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Formative Assessment for/as Learning

Eva Kleinlein; Valerio Rigo; and Alessandra Imperio

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Example of Learning Unit where learning and assessment co-occur in a perspective of formative assessment, assessment for learning (AfL) and assessment as learning (AaL).

Learning framework of reference: Thinking Actively in a Social Context (Wallace, 2001).

Topic: Counting with the help of the hand’s fingers.

Class: primary school – 1st grade.

Previous knowledge: numbers from 1 to 20, the concept of addition, counting on fingers to solve an addition with numbers from 1 to 10.

Lesson Plan

Table 1: Planning was designed and implemented by Dr. Alessandra Imperio in her classroom.

| N. | Stage | Activity |

| 1 | GATHER/ORGANISE What do I know about this?

|

What do you know about counting with your fingers? How do you count with your fingers when you do addition? Students reflect on their previous knowledge and respond. The teacher reports the collected information on the blackboard. |

| 2 | IDENTIFY What is the task? | The teacher explains that today the children will find out how to count by helping themselves with their fingers when the two addends do not fit together on their fingers. e.g., 7+5= |

| 3 | GENERATE How many ideas can I think of? | Try doing 7+5 with your fingers. Since we only have ten fingers, think of all the possible ideas to solve this addition problem, still helping with your hands. Children think individually about all the possible solutions. |

| 4 | DECIDE Which is the best idea? | Pairwise comparison of the solutions found and choice of the best one. |

| 5 | COMMUNICATE Let’s tell someone! | Pairs tell the class about the decided solution. Real solutions found by the children were: – I use my hands and feet. – I keep the first number in mind and place the second in my hands, then count. – I pretend that 7 is a 2 and put both 2 and 5 on my hands, then add up. – I use two hands and then use one hand again. |

| 6 | EVALUATE How well did I do? | Children experiment with the proposed solutions and assess them in terms of effectiveness (does it work or not work?) and efficiency (is it convenient? is it practicable?). Voting. |

| 7 | APPLY Let’s do it! | Children use the chosen method (I keep the first number in mind and place the second in my hands, then count) to perform some sums. |

| 8 | LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE What have I learned? | What have we learned? Children reflect on what they have learned and how they can reuse it with other operations. |

In the example given, children were guided and supported in the co-construction of new knowledge anchored in prior knowledge, which is the identification of a method for solving addition with fingers with numbers whose sum reaches up to 20. The teacher assessed the pair’s work during learning without formalising it, taking notes of evidence and feedback provided to each couple to document each student’s progress. Indeed, the learning plan allowed children’s thoughts and their progress in acquiring a new strategy to be visible without the need to schedule a written test. The teacher helped the children self-assess their solutions in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, supporting each one’s work with the feedback needed to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each proposal (see the paragraph “Purposes” for a better understanding of how inclusion can be supported). It is a clear example of formative assessment with the twofold purpose of assessment for learning (AfL) and assessment as learning (AaL). Indeed, the teacher used feedback and ongoing support to provide clear direction for students’ learning improvement (AfL). At the same time, she helped students develop and master thinking skills (AaL) to reflect on the task and solutions.

Dr. Alessandra Imperio, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- WHY do we do assessments?

- WHEN should assessment take place in the learning process?

- HOW are assessment processes generally structured?

- WHAT are the possible focuses of assessment in education?

- WHO should be involved in the assessment processes?

Introduction to Topic

The chapter maps out different aspects and concerns of assessment in education. However, it does not claim to cover all the issues that such a complex topic can address but only offers insights from where to start and which need further study. We highlight five areas of interest: First, we distinguish three distinct purposes of assessment (as, for, and of learning). Secondly, assessment can occur at different learning moments (before, during, and after learning). Thirdly, assessment processes are to be divided into three key steps (strategies, criteria, and outcome). Furthermore, it is essential to line out the overall focus of the assessment (competencies, environment, and capabilities) and to consider the various actors that can be involved in assessment processes (teachers, parents, students, peers, and other “experts”). We portray some of the most essential aspects, inherent questions, concerns, and potential within each area. By doing this, we conclude by elaborating on the role of inclusion in every subsection of the assessment process.

Building upon an example from teachers’ practice and experience with assessment, we will describe inherent challenges and risks that must be addressed as a crucial part of ethical considerations. Initial questions will then guide the structure of the chapter. Following the introduction of the topic, critical areas of assessment in education will be presented in detail. We will conclude the chapter by suggesting some closing questions for further discussion.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations must be addressed when elaborating on educational assessment. The following subsections outline the specific potential of formative assessment strategies for inclusive contexts, difficulties, dilemmas, and challenges. These must not be neglected but critically and carefully examined. First, it is crucial to keep in mind the societal system that schools are part of. Schools follow allocative functions within a society where performance and achievements are of great importance, like in meritocracy (Trautmann & Wischer, 2011). Therefore, schools significantly impact the social placement of learners in the greater society (University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing 2010: 602). In practice, the social order of individuals is influenced in some countries by the division of pupils among different types of schools and by the distribution of differently valued school degrees. These practices within the school system led to unequal opportunities in a meritocratic society. Even though these aspects counteract the overarching aim of community and school for all, they must be considered pre-conditions framing the topic of assessment in education.

In addition, questions on the fundamental aim and necessity of assessment and education arise within ethical considerations regarding assessment in education. Possible underlying and relevant questions in this context are, for example: ‘Why do we do an assessment?’, ‘What is learning, education, and development?’, ‘How can we measure learning and development?’, ‘What role does assessment have in education?’ While some of these questions are tackled more directly in the following subchapters, others can be understood as questions for (self-)reflection, and discussion and their careful consideration may promote more equality and justice within the field of educational assessment.

Assessment – What are we talking about?

Assessment is a contested and highly debated field, especially regarding inclusive education. To provide a comprehensive overview of related terms, concepts, and assumptions, it is first necessary to focus on the concept’s meaning and distinguish it from other associated words like diagnostics and evaluation. On the one hand, following Ingenkamp & Lissmann (2005), educational diagnostic aims to identify individual pre-conditions and learning processes through diverse diagnostic activities to optimise individual learning. On the other hand, depending on the source, assessment and evaluation can be treated as synonyms or as distinct concepts (Apple, Ellis & Hintze, 2016; Hus & Matjašič, 2017). We understand evaluation in education as the “process used for judging quality” (Apple, 1991, as cited in Apple, Ellis & Hintze, 2016: 53) which determines the extent to which goals have been achieved based on a standard (Apple, Ellis & Hintze, 2016; Surbhi, 2017).

Assessment, instead, can be described as “the process of finding and interpreting evidence to be used by learners and teachers to enable them to establish exactly where the learners are in their learning, where they have to focus, and what is the best way to get there” (Hus & Matjašič, 2017). Thus, assessment is process-oriented as it is based on continuous observations to provide feedback and identify areas of improvement, while evaluation is more product/outcome-oriented, for example, success and failure (Apple, Ellis, & Hintze, 2016; Surbhi, 2017). Therefore, even if the main focus of this chapter is the assessment, while talking about assessment these conceptual constructs (evaluation, diagnostics) are also taken into account. Furthermore, assessment can in general take place at an individual, classroom, school, regional, or even internal level; this chapter however mainly concentrates on the individual and classroom perspective.

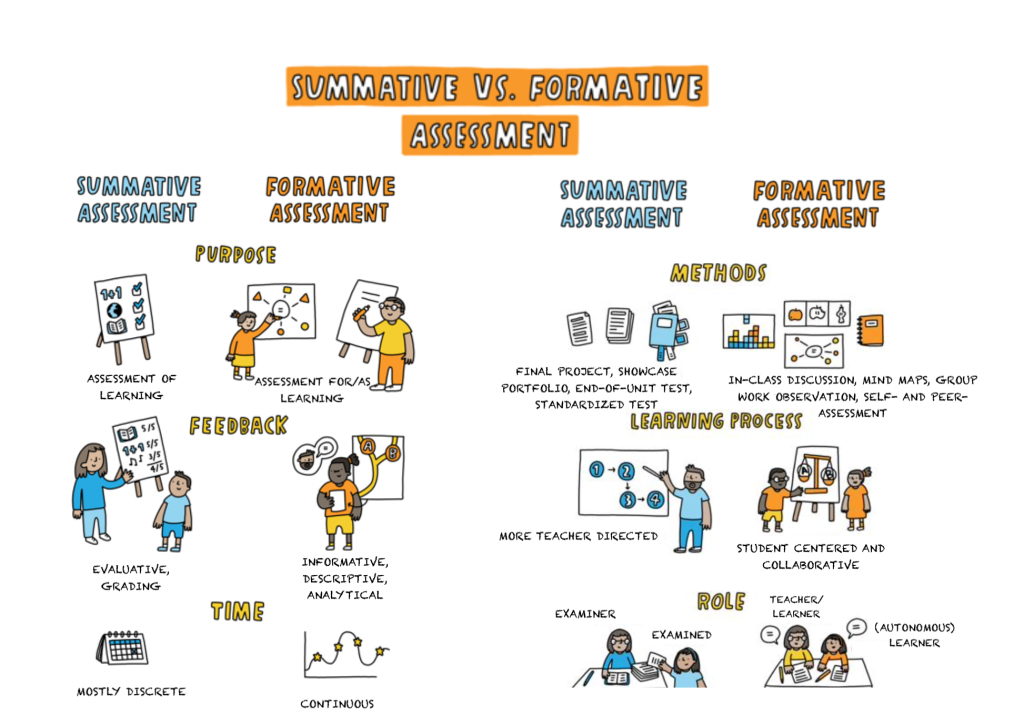

Building upon these considerations, two main types of assessment can be differentiated: summative and formative assessment. While summative assessment mainly serves “the purposes of accountability, ranking, or certifying competence by the judgement of students’ achievement” (Schellekens et al., 2021: 1), formative assessment primarily “supports and improves students’ learning” (Schellekens et al., 2021: 1). Originally, formative assessment was conceived as an aid to teaching to align instruction with the emerging needs of students (Bloom, 1969). Thus, the focus is on the teacher, who can adjust instructional choices based on their students’ learning needs. However, the term “formative” lends itself to various interpretations (Broadfoot et al., 1999).

For this reason, while the literature acknowledges that the expression formative assessment does not precisely align with those of assessment for learning or assessment as learning, in this chapter, we have considered the expression “formative” in a broader sense. Specifically, we define “formative” as encompassing all forms of assessment that actively influence student learning and refine their learning trajectory, similar to how life experiences shape personal growth.

Therefore, especially formative assessment is of great relevance for inclusive education and education for all. The formative role of assessment supports overcoming comparative and stigmatising perspectives on the students and thus has the potential to enable a more inclusive assessment. The picture below summarises the main differences between them.

Figure 1: Summative vs. formative assessment

Key aspects

Purposes – WHY do we do assessments?

As suggested by Earl and colleagues (2006), the first question a teacher should ask himself/herself is not “how do I assess?” but “why do I want to assess, or do I need to assess?” Therefore, this means identifying the purpose of assessment since this has several implications: the role played by teachers and students, the teaching-learning process, and the choice of assessment methods. All these mentioned aspects are directly related to the Teacher Habitus. Three distinct but interrelated purposes of assessment are highlighted in the literature: Assessment OF Learning (AoL), Assessment FOR Learning (AfL), and Assessment AS Learning (AaL). There are several definitions of the three, and, more generally, each purpose simply corresponds to a type of approach to assessment (Schellekens et al., 2021). For teachers, it might be more practicable to reflect on the three as purposes in order to guide their actions and consequently, their approach to assessment. Arguably, following this route is easier to handle the many definitions and nuances in the literature. Moreover, by thinking of them as purposes, it is relevant to be aware that it is difficult to fulfil the three purposes at the same time; however, it is valuable to know them and to recognise the need to find the right balance between them (Earl et al., 2006). The following information on the assessment of/for/as learning is a brief compilation that has considered some of the existing resources in the literature (Alberta Education, 2003; Earl et al., 2006; Harapnuik, 2020; Schellekens et al., 2021).

Assessment OF Learning

AoL is the best-known purpose of assessment, as it reflects the traditional assessment perspective for most of the 20th century. AoL aims to certify competence or inform parents or other stakeholders about the student’s proficiency concerning the learning outcomes of the curriculum. It is a summative assessment in nature, it is formal, and it usually occurs at the end of a training or a learning unit. It consists of collecting information on what extent students can apply knowledge, skills, and attitudes against a standard. There are many methods to collect this information, but they are not exclusive to this assessment purpose. For instance, they can be tests, presentations, or other written, oral, or visual methods. The assessment finishes with the assignment of a mark or comment on the product or performance. The role of the teacher is to grade achievement by considering students’ products and processes and reporting this information. Usually, the teacher’s grade or comment is used as an indicator of the student’s level of success.

Assessment FOR Learning

When the purpose is to improve learning, it is called AfL. It is a formative in nature and is an integral part of the learning process. Thus, it is an ongoing process involving formal and informal assessment activities designed to modify teaching according to students’ needs and to provide students with specific feedback that they can use to improve learning. Therefore, to adjust and target teaching planning to move students’ learning forward through precise feedback, it becomes necessary to make student learning visible. The main elements are descriptive feedback, as an example of what good work looks like, ongoing support, and peer collaboration. Feedback provides clear direction for improvement but also recognition of achievement. For gathering pieces of evidence, focused observation, videotapes, or audiotapes may be helpful; several strategies and methods can also be employed to make learning visible, including Cooperative learning activities. Teachers and peers play a central role in this.

Assessment AS Learning

Finally, when the assessment aims to give opportunities to students to critically reflect on their work, to understand how to independently pursue their acquirements or, in other words, to promote deeper learning, develop metacognitive strategies and learn how to learn, in that case, we are talking about AaL. AaL has a formative nature. Students use formal and informal feedback and self-assessment to figure out how to continue learning. Since it is a reflective process, it should take place continuously. There are many methods for students to reflect on their learning, such as criteria, rubrics, and checklists. This approach to assessment involves each student and their peers. In this case, the teacher’s role is to help students develop, master, and feel comfortable with these metacognitive strategies.

How can these assessment purposes sustain inclusion?

We can plan and employ inclusive assessment strategies with all three assessment approaches. In the case of AoL, assessment can be inclusive, for instance when you allow each student to decide in which form they want to show and make their learning visible. For example, a student can choose to show his/her learning in a written, oral, visual, or dramatic form. AfL might be more inclusive if the feedback is provided to each student individually or in a group since it is individualised for everybody in the class. Each student or group may receive specific material and guidance they need to progress. Finally, AaL gives you the foundation to be inclusive since students develop metacognitive skills that can help them become creators of their learning, with their own times and individual strengths.

Moments – WHEN should assessment take place in the learning process?

Time management is one of the most important things to remember when it comes to formative assessment. As the French pedagogist Philippe Perrenoud reminds us, we cannot introduce formative assessment in schools without a radical change in traditional educational institutions (Perrenoud, 2005, 1999). In fact, one of the crucial changes in this regard is related to time management. In the assessment process, we can identify three central moments in which assessment can take place: “before,” “during,” and “after” the learning process. How we give meaning to these three steps is different for each teacher and reveals the reasons why we decide to conduct an assessment and, more generally, why we teach. We can see the initial phase as a diagnostic phase, in which the teacher considers the level reached by the pupils and their needs. However, analysing needs as a diagnosis carries a risk: privileging the selective dimension of evaluation over the formative one, thus limiting oneself to giving a static interpretation of a given moment. We must encourage a dynamic and open understanding of the processes that take place within the classroom and are in constant flux. In this phase, the assessment process must establish the learning objectives and the criteria for success (Black and Wiliam, 1998). If we do not establish criteria, students are disoriented and do not understand what they can gain from this learning experience. Furthermore, the “before” phase is also the planning phase, which is also the phase we should refer to at the end of the learning process. The planning phase is not a simple conception of activities but aims to identify the final goals and the means we can use to achieve them. Planning is always a contextualised phenomenon in the classroom and, therefore, always starts from the needs of each student. It is not something implicit, and it is not something clear only from the teacher’s perspective. Still, it must be as explicit as possible to communicate to the pupils where they are in their learning journey and what gap separates them from the point they want to reach. Furthermore, the design must be open to new contributions and possible modifications throughout the school year. Finally, assessing is for learning and creating new learning opportunities. Therefore, the teacher must learn from the assessment journey and return to the planning to understand its possible developments and improvements. The ‘before’ phase is also a time when teamwork can take place (Teamwork in the classroom). Teachers at this stage can share their views on the planning and the objectives. In this sense, the possibility of having an interdisciplinary perspective is valuable for all those involved in the evaluation process. From an AaL perspective, for students, the “before” phase may represent an occasion to conduct self-assessment to better understand the level of knowledge already possessed when fragments of memory are collected and organised. They will eventually anchor this knowledge to the one they already acquired.

The “during” phase is the part of conducting activities, the stage in which pupils play an active role that can provide the teacher with an opportunity to gather evidence (Carr, 2012, 2001; Giudici & Rinaldi, 2011). It is not enough to have strong listening or observational skills, and the teacher must no longer be the leading actor in what happens within the classroom. If we want to gather evidence about what our pupils can do, it is first necessary to allow them to act freely. Celestìn Freinet (as cited in Bottero, 2021) reminds us that everybody wants to be allowed to choose their work freely, even if such a choice sometimes is not convenient. Leaving pupils free to choose allows them to discover more about their tastes, inclinations, and needs. At this stage, it is essential to rethink the value of observation and documentation. These tools allow teachers to gather evidence in a completely different way from a simple test or homework assignment. To observe, the teacher must ensure that the pupil can act freely without depending on the adult’s guidance. However, there is a second aspect that we must bear in mind when we speak of observation and documentation, namely the fact that it is impossible to observe and, therefore, document everything that takes place within the classroom. It is, therefore, necessary to have already prepared the time and way to conduct the observation in the planning phase.

The most characteristic phase to consider when reflecting on different moments is what we refer to as the “after.” There are several possible “after” types: we can mean the end of a unit of learning, the end of a school year, or the end of a study cycle. By and large, only if assessment becomes a tool that follows the student even after the learning journey can we call it formative. A purely summative assessment usually ends with the final return of the test result. In contrast, a practical formative assessment should pose as a continuous process that allows students to find in the assessment a functional element for any other future learning. In this sense, all learning never ends in itself but stimulates the search for new horizons of growth. One example of the “after” phase can be the simple use of the “ticket to leave” teaching strategy. It can reinforce new knowledge, provide a time for reflection, and/or allow the teacher to evaluate what students will take home. It will help the teacher decide whether to dwell on the topic further. Before students leave, they hand in a “ticket” with an answer to a question about what they learned (for example, what do you think you learned today? Do you have a question to ask about something you didn’t understand?) The exit tickets help you plan the next lesson or unit of learning.

How can these assessment moments sustain inclusion?

Of the three stages reported here, the last one, the after moment, is the one that would be most appropriate to look at from an inclusive perspective. On the one hand, this perspective allows teachers to look beyond the hindrances or difficulties encountered by pupils with special educational needs; on the other hand, it allows them to reconsider learning objectives from the student’s own needs (Lepri, 2021). The idea of adopting a long-range evaluative perspective that looks at students’ personal futures and their need for self-determination is an essential step if we are to ensure that schools truly help each student cultivate his or her potential. From this perspective, any assessment that claims to be formative must necessarily take time, seeking to understand learning processes in their complexity (Vertecchi & Bonazza, 2022).

Structure – HOW are assessment processes generally structured?

Even though assessment processes can have many different focuses and approaches, it can be noted that there is an overall structure of assessment that tends to stay the same: We apply certain categories, use certain strategies, and aim for a certain outcome of an assessment. These structural aspects of assessment are not only the same for educational assessment processes but can also be found in other disciplines that work with assessment, for example, in health care, medicine, and psychology (Madden et al., 2007; Schliehe & Ewert, 2013; World Health Organization, 2021). In the following, an overview of categories, strategies, and outcomes of assessment in education is provided. Within each of these aspects, a huge variety of embodiments that consequently lead to different kinds of assessment can be identified. The chapter aims at giving an overview of educational assessment by presenting how an inclusive structure of assessment could look like in theory and practice.

Categories of Assessment

Firstly, categories are one of the main issues of assessment processes. As the use of categories raises many concerns “such as stigmatisation, peer rejection, and lowered self-evaluation [as well as] […] problems of reliability and validity” (Florian et al., 2006: 37), a careful reflection of this aspect is important. Despite these concerns, it must be noted that categories are necessary for thinking, in general, and assessment, in particular (Katzenbach, 2015). With regard toassessment “systems of classification [thus] remain an important way of organising information so that it can be passed to others, and they provide a framework to guide intervention” (Florian et al., 2006: 37).

Therefore, especially in assessment, categories that suitably describe what has been or what will be assessed are necessary. The suitability of these categories, nevertheless, can vary in many ways. On the one hand, categories of assessment can be standardised, pre-defined, and for example, based on curricula or certain diagnostic tests. These types of categories can therefore be considered deductive categories, as they arise from theories or specific category systems, for example, ICD or ICF of the World Health Organization 2001, 2005. Deductive categories, in general, promise somewhat higher comparability as the same set of categories is used in different contexts and assessment processes. Hence, they are, for instance, used to justify the allocation of resources (Florian et al., 2006: 39). On the other hand,inductive categories can also be used. These kinds of categories of assessment arise during the assessment process and teachers, as well as students, can be creators of these categories. Consequently, their experiences and practices have a direct impact on the development of these kinds of categories. Therefore, inductive categories might generally be considered to be more accurate and precise, but at the same time, their specificity and individuality might complicate comparability.

With regard to categories for inclusive assessment, a critical examination of enabling and stigmatising effects thus is crucial (Florian et al., 2006: 39). While there are deductive criteria like those from the ICF (World Health Organization, 2005) that can contribute to inclusive assessment, other deductive criteria that focus on disabilities, for example ICD(World Health Organization, 2001) tend not to support this perspective. However, inductively generated criteria can support inclusive approaches as they are developed very flexibly, individually, and are practice-based. Nevertheless, this kind of category tends to bear the risk of overseeing aspects that are not at the centre of attention and generating new, possibly stigmatising criteria.

Overall, it is possible to assess development and learning with a variety of open, flexible, and inductively generated criteria as well as with pre-fixed, theory-based, and deductively generated criteria. While all these options go along with certain advantages and consequences, it is particularly important to keep the inevitable risk of categories in general in mind (Florian et al., 2006). As Boger (2017) points out, inclusion can always only fulfil two of the three basic propositions that are crucial for inclusion: empowerment, normalisation, and deconstruction. Following this, empowerment and normalisation are impossible when not using some kind of category (Boger, 2017). And as long ascategories are in place, there is a risk that they are used in discrediting ways (Katzenbach, 2015). In order to prevent and counteract stigmatisation, this risk must be considered when using standardised as well as more open categories.

Strategies of Assessment

In addition to the critical examination of appropriate and meaningful assessment categories, also a reflection on the suitability of possible tools of assessment, respectively assessment strategies are crucial. Within assessment strategies, we can broadly distinguish between two modes. Firstly, strategies of assessment can be designed in a rather obvious and standardised way and for instance rely on (multiple-choice) tests, quizzes, dictations, and examinations (Schäfer & Rittmeyer, 2015). Secondly, strategies of assessment can also be rather open and flexible and thus rely on the collection of evidence during the learning process for making learning visible (Mughini, Panzavolta, 2020). Materials such as students’ drawings, texts, or classroom observations could thus be of interest (Earl & Katz 2006: 17). Moreover, materials that develop in the contexts of students’ demonstrations, discussions, projects (ibid.), Inclusive Play, or on the basis of (Digital) media & materials for learning can be included in the assessment process. This way, learning and assessment processes take place simultaneously, as promoted by the formative assessment perspective.

In the light of inclusive assessment strategies, many of the before-mentioned forms are generally conceivable and verifiable if connected to suitable categories and outcomes of the assessment. While some situations, contexts, or needs might give valuable reasons to use standardised assessment strategies (for example, for official documentation or resource allocation), assessment strategies that are more flexible and student-oriented can especially be considered important for inclusive settings, as they provide very individual information on the student. Even though rather open approaches and inductive analyses might not withstand the quality criteria of standardised tests, they are of high relevance for inclusive assessment as they enable the collection of rich qualitative data on the student’s learning and development process. The flexible and reflected use of assessment strategies in light of the particular situation and aim of the assessment is thus necessary to gain deep and meaningful insights and conduct a suitable assessment, or as Bourke and Mentis (2014: 395) state: “Ultimately, teachers’ choices about the assessment practices they use for learners […] reflect their views about teaching, assessment, and learning and must therefore be both a conscious and informed decision, while weighing up ethical dilemmas that arise.”

Outcome of Assessment

The third aspect that must be highlighted when elaborating on the assessment structure is the outcome of the assessment. The main focus that is generally put on assessment outcomes is feed-back. Feedback is a crucial part of the process, as it provides an overview and insight into what has been done and what has been reached in the past process. Therefore, written and oral feedback, structured and semi-structured, as well as standardised and open feedback, can be used (Bastian et al., 2018; Halverson, 2010; Ibrahim et al., 2021). Very common assessment outcomes are marks and grades, whereas learning reports and other more open feedback formats are still used but these are used primarily in lower grades. In this respect, it is interesting to look at a specific case.

As of the school year 2020-2021, the Italian Ministry of Education has proposed a new, more formative-oriented mode of assessment in the final report. Instead of numerical grades, so-called ‘descriptive judgments’ have been introduced, which require the teacher to ask about four dimensions relating to achieving the set goals. These are the continuity with which learning occurs, the autonomy with which it is conducted, the type of resources the pupil uses spontaneously, and whether the learning situation was previously known or unknown. This tool allows pupils to reflect much more deeply on their learning-to-learn competence, enhancing metacognitive processes in a formative perspective.

In light of inclusion, feedback should provide a resource-oriented perspective with detailed information about the learning process, and achievements (Brooks et al., 2019). While feedback is a crucial part of the assessment process, one outcome that is often neglected is a form of feed-forward. Feedforward can be understood as the outcome of assessment contributing to the improvement of the situation that has been found in the past assessment process (Brooks et al., 2019:10). In order to promote the learning and development of students, feedforward thus plays a key role. It provides information about possible next learning steps and related ideas, adaptions, and interventions that could be considered to improve students’ learning and development. In this way, a feedforward can help to shift the view from the past and the question of ‘what has been reached or done?’ to the future and the question of ‘what could be reached or done?’

In order to develop inclusive assessment outcomes, it is generally important to not only provide meaningful feed-back but also feed-forward, as “the provision of feedback is no guarantee of it being used” (Brooks et al., 2019: 7). Therefore, the outcome of the assessment can be considered the most supportive for inclusive education if it is process-oriented and provides information that can be considered for the arrangement of future learning and development processes and thus promote learning (Brooks et al., 2019). Moreover, it is necessary to reflect on the question of to whom feed-back and feed-forward are addressed? The shape and content of the outcome must be aligned with the expected recipients in order to fulfil the aims that were fixed in advance. Building on that, the outcome should provide meaningful information for the involved actors on how future learning processes could be designed and what adaptations and changes can be done.

How can this assessment structure sustain inclusion?

With regard to an inclusive structure of assessment, it is necessary to carefully consider the inclusivity and suitability of all three before-mentioned aspects: categories, strategies, and outcomes must correspond with the addressed student(s) (for example, Relationships, Sex/Gender, interests, needs, prior knowledge,…), the situation, and the aim of the assessment. Only if all three structural aspects are extensively elaborated and mutually consistent, can assessment promote learning and thus can be considered as inclusive and wholesome.

Focus – WHAT are the possible focusses of assessment in education?

One of the main aspects to consider is, “what do we want to assess?” This is usually competencies. Competencies involve the individual in a holistic perspective and are related to skills and abilities; these three help convey a broad idea of what a student can do to activate cognitive, meta-cognitive, emotional, social, and physical processes. Precisely because of its multifaceted nature, we can only observe the manifestation of competence when the student is in action and is enabled to act and mobilise different types of personal resources (for example, knowledge, skills, and attitudes). Moreover, competence is not reducible to an abstract concept but is always related to specific social, cultural, and operational contexts. Content knowledge accounts for only a tiny part of these processes, but it is often the element teachers promoting purely summative assessment tend to value most. Conversely, students should be able to understand their strengths and weaknesses, be encouraged to act autonomously, and face new challenges and unknown problematic situations, which means to “know what to do when you don’t know what to do” (Claxton, 1998). However, we cannot limit ourselves to considering skills and competencies as the sole object of evaluation. The quality of the learning environment must be kept in mind when we look at all the potential inherent to the learning process. If it does not guarantee the student the fundamental elements for their development and growth, we must reflect on this aspect and try to change the learning situation. There are no neutral choices in education. To take care of the learning environment means reflecting on how students are enabled and supported to interact with each other, how free they are to explore the school environment and how they can be open to new knowledge and modes of exploration. Assessing a student without considering the potential offered by the learning environment and the obstacles it may pose does not help us fully understand the resources available to our students.

Now, let’s take a step back and ask ourselves for which purposes we assess. Undoubtedly, one of the main tasks of the school should be to help students discover their interests and passions. However, the possibility of making such a discovery should not be taken for granted. Although a student may have an idea of what they like as early as primary school, it may not necessarily manifest itself. Often, a child needs a long time to explore the world around them to understand what they like. The assessment process plays an essential role in this possibility of discovery and can inhibit or facilitate the exploration of yet unfamiliar activities and contexts. Self-assessment is a tool for students to gain critical awareness in this regard. To this end, we may use the so-called narrative assessment. This tool allows the pupils to recount what they consider to be the strengths and weaknesses of something they have experienced. Finally, it is possible to see the focus on the learning environment and the competencies in a new light, which is the development of capabilities. When we think about assessment, we must also ask ourselves what our pupils are capable of being and doing. This perspective would be helpful in considering well-being, happiness, and self-realisation as possibly essential acquisitions of the whole assessment process. Capabilities are the most important opportunities the learning context offers the students to start realising a kind of life they have reason to value. Assessment could be a powerful leverage to help them understand such opportunities’ existence and potential.

How can these assessment focuses sustain inclusion?

From the perspective of inclusive pedagogy, the development of capabilities provides for greater involvement of students’ voice to achieve personalised learning objectives. We should not forget that assessment on the one hand determines the balance of power in the teaching-learning process and, on the other hand, establishes what is important within it, giving relevance to one learning content over another (Cottini, 2021). Giving voice to the aspirations, goals, and life plans of students with special educational needs means recognising the pluralism of values that should be an indispensable element of democratic learning. It also means, above all, recognising people with their emotional and existential experience, truly making room for diversity.

Actors – WHO should be involved in the assessment processes?

Last but not least, the question to be tackled in this context is about who is and who should be involved in the assessment processes? As assessment processes are very complex, numerous actors may be involved. In particular, it is important to keep in mind that it is not only about who is contributing to the assessment and considered to have valuable information but also about who is being assessed. In order to line out more clearly which actors could, and possibly should, be involved in the different stages of assessment processes, the following subsections address this question in more detail.

Students

The first group of actors that must be considered in the assessment process is students. Especially in light of inclusive assessment, it is necessary to focus on all instead of focusing on some students (Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2011). Every student brings particular competencies, interests, capabilities, and needs towards their environment to the classroom. In order to address this diversity (for example, language, Sex/Gender education), and enable active and meaningful participation of all, it is necessary to consider each student. Therefore, group assessment, as well as self-assessment strategies, can be valuable. Students thus must not only be considered as the centre of assessment but also as valuable actors in assessment. According to the Social Childhood Studies paradigm, children take on the role of expert actors and main informants in their own lives and for this reason, they should be consulted and involved in decision-making processes that affect them (Kampmann, 2014; Levin, 2013; Melton et al., 2014). This paradigmatic shift through students’ voices and active participation can also have interesting implications in assessment practices. Alongside, in the case of students in higher grades and school orders, according to the Student Voice Movement (Grion & Cook-Sather, 2013), it is about empowering them to have a voice in the life contexts they experience. Active involvement and participation of children and teenagers in assessment practices can be realised not only in assessment and peer assessment activities, indeed, just students can, for example, co-construct checklists, assessment rubrics and, more generally, define assessment criteria with their teachers (or independently) (Grion, 2014; categories of assessment). They can also choose how to demonstrate learning and thus have a voice in the choice of the assessment tool (strategies of assessment). A helpful tool for stimulating pupil participation is what Celestin Freinet (Bottero, 2021) called brevet (patents), a term he took from the scout movement founded by Baden-Powell. It is a kind of certificate of acquisition of a skill or competence that the pupil demonstrates having acquired following a specific performance and comparison with the class group. The pupils freely choose when to try to achieve such recognition based on what they feel they have learned so far. This free choice allows pupils to gain an essential awareness of what they can do, or not, by facilitating the self-assessment process.

Teachers

In addition to the students, another critical role is played by teachers. Teachers interact with their students on a daily basisand have an immense impact on their students’ learning and development process. Therefore, their role in the assessment process is also crucial. All teachers should be considered here: class teachers, subject teachers and special educators.Depending on the aim and context of the assessment, it can be helpful and reasonable to involve only specific teachers, for instance, certain subject teachers or a wider group of teachers and educators (Galloway et al., 2013). In order to gain a broad overview of possible restraining factors and barriers for learners, and obtain a more holistic view of the situation, consultation and involvement of a wide range of (pedagogical) actors is often necessary. Therefore, also a reflected decision on Strategies of Assessment is crucial, and especially with regard to Relationships and Teamwork in the classroom, the inclusion of perspectives of different educators can be helpful.

Moreover, teachers’ self-reflection and habitus play a crucial role in assessment. Teachers, but also other actors that are involved in the assessment processes inevitably maintain certain presumptions or even biases that, as a consequence, can affect the assessment, if it is not critically examined and reflected upon. In addition, also trust between the different actors plays a crucial role in assessment processes. Teachers especially are thus asked to establish a mutual and trustworthy relationship among the involved actors. Another aspect to be considered here, is the possibility to assess teachers from the perspective of students, parents, and legal guardians. While teachers mostly are in the role of assessing students, it is thus also possible to assess the teachers’ work. This is especially of high importance, as teachers’ ability to provide meaningful learning opportunities has a great impact on the student’s learning and development process and thus should also be assessed. In particular, it must be borne in mind that if an assessment is indeed formative, then the responsibility for a negative outcome of the teaching-learning process no longer lies with the students. In an effectively formative perspective, those who must question their choices and ask why students did not achieve the desired results therefore are the teachers. Accordingly, teachers should rethink their design choices and improve the learning environment for their students’ learning in the future.

Parents & Legal Guardians

Another important role in the assessment process is played by parents, caregivers, and legal guardians. These actors often have another and very important perspective on the childs’ competencies, interests, capabilities, and needs towards the environment. As parents and legal guardians mostly interact with the child in situations and ways that are to a great extent contrasting to the teacher’s perspective, their knowledge and opinion are highly valuable for the assessment process and for a wholesome comprehension of the situation (Bastian et al., 2018; Galloway et al., 2013). Therefore, it is necessary not only to involve parents and legal guardians in the assessment, but to carefully pay attention to their views and experiences, to involve them equally, and to ensure favourable communication. A careful consideration of eligible Strategies of Assessment, and Outcomes of Assessment, therefore, are necessary to ensure good and purposeful cooperation.

Other “Experts”

In addition to the aforementioned groups of actors, also other “experts” can be involved in the assessment. The involvement often not only depends on regional or national rules and regulations for educational assessment, but also on the specific case, situation, and aim of the particular assessment (Galloway et al., 2013). Actors that are frequently considered experts for assessment processes are, for example, medical doctors, psychologists, social workers, and youth welfare workers but also health care workers, teaching assistants, and physiotherapists can and are valuable contributors to assessment. The benefit of contributions of the different kinds of other experts must be carefully reflected upon in order to include all views and opinions that are necessary to enable a comprehensive and meaningful assessment process.

How can these actors sustain inclusion?

With regard to actors of inclusive assessment, equal involvement and careful consideration of diverse groups must be stressed. Therefore, it is essential to pay attention to different perspectives and experiences that are in place and to enable communication and decision-making. This is especially crucial for the involvement of students and peers, as well as of parents and legal guardians, as their experiences are often not considered and valued enough in assessment processes. Moreover, it is necessary to keep in mind that the described actors are not only part of the assessment process but also of the learning and development processes that precede and follow. Careful consideration of the actors’ different positions, contributions, and demands thus is important in all steps of learning and assessment.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

While the chapter on assessment certainly provides a broad overview of the topic and outlines key aspects that must be considered, the flexible and reflected use of assessment in light of the particular situation and aim of the assessment is thus necessary to gain deep and meaningful insights and conduct suitable assessments in specific situations. In order to support this reflective process we provide questions for discussion and reflection that can be addressed individually or as a team. The questions tackle the various aspects that were mentioned in the previous sections and help teachers to develop specific assessment strategies for practical use in their everyday practice.

WHY: Why do we do assessment?

- Why do I want/need to assess?

- May I fulfil a summative and a formative assessment at the same time?

- How can I make assessment of learning inclusive and fair?

- How can I make assessment for learning inclusive and fair?

- How can I make assessment as learning inclusive and fair?

- Which of the three purposes/approaches to assessment should be pursued most? For what reason?

WHEN: When should assessment take place in the learning process?

- What happens before the assessment?

- What happens during the assessment?

- What happens after the assessment?

- Which role does planning play in the different phases of the assessment process?

HOW: How are assessment processes generally structured?

- Do I have a clear and well-founded aim and focus of assessment and what is it?

- Should I work with inductively or deductively generated categories and why so?

- Which categories can I use and what are possible risks and side-effects?

- Which strategies and tools of assessment can I use to gain deep and holistic insights?

- How do the assessment strategies compliment or overlap with one another?

- Is the outcome of assessment a feedback, a feedforward or both?

- What outcome is necessary to improve the student’s situation?

- Which categories, strategies, and outcomes are necessary to reach the pre-defined aim of the assessment?

WHAT: What are possible focuses of assessment in education?

- Which role do competencies, abilities, and knowledge play in the assessment process?

- Why is it important to consider hindrances and opportunities related to the classroom environment?

- How can the interests of every single student be better involved in the assessment?

- What kind of contribution could a capability-based perspective offer to the assessment process?

WHO: Who should be involved in the assessment processes?

- Who or what is in the centre of assessment / who or what is assessed?

- Which actors can contribute valuable information to the assessment?

- How can I establish a trustful atmosphere with all the involved actors?

- Are all necessary perspectives considered or did I inadvertently omit something or someone?

Moreover, it might also be interesting to reflect on or discuss the following questions that were posed at the beginning of the chapter:

- What are learning, education, and development?

- How can we measure learning and development?

- What role does assessment have in education?

Overall, careful consideration of all the above-mentioned questions is necessary to ensure and strengthen equality and justice within the field of educational assessment.