Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Formative Assessment put into Practice

Vana Chiou; Janneke Eising; Pamela February; and Melike Özüdoğru

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Leah has just graduated and is a novice teacher who was given a grade 7 class at the beginning of the year. She has 32 learners in her class, and she is excited to work with her first class. From what she has learned so far, they come from diverse backgrounds with different interests, learning abilities, and needs. Their diversity is not an issue for her as she really wants to accommodate all her learners and create a safe, welcoming, and inclusive learning environment. Leah would like to try more formative assessments to assist her in catering to all her learners, but she has heard from others that it is time-consuming and difficult to execute in larger classes.”

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- Why should we employ formative assessments in inclusive classrooms?

- How can teachers be encouraged to use formative assessment in their classrooms?

- Can this be done in small steps without disrupting the class?

Introduction to Topic

Leah’s perception of formative assessment is similar to that of many teachers, be they novices or more experienced teachers. Formative assessment has been around for as long as summative assessment has and is regarded as essential to education. However, the implementation of formative assessment appears to create “assessment tension” in teachers, according to Chan and Tan (2022). Assessment tension is created when education policies and reforms around formative assessment appear to be “required” of teachers and they may not be ready for these changes. They may also see formative assessment as being time-consuming. In addition, teachers see large classes as a barrier when implementing formative assessment because the perception is that the activities related to formative assessment take even longer with larger classes. So how do we address these perceptions of teachers? According to Widiastuti and colleagues (2020), a positive belief by teachers in formative assessment is the result of having a strong understanding of the benefits of using formative assessment in the classroom. In turn, these beliefs impact the way teachers implement formative assessment and how they make decisions regarding the learning outcomes achieved by learners. Thus, the successful implementation of formative assessment depends on the knowledge and skills teachers have on the topic, their attitudes, and beliefs towards the value of using formative assessment and whether their classroom practices regarding formative assessment enhance the learning outcomes for their learners.

This chapter aims to unpack formative assessment as a concept, delve into five key strategies, and show its connectedness to classroom practices and ideologies that well-trained teachers already believe in. Furthermore, the chapter links these key strategies to success criteria that teachers use in their daily teaching. What makes the chapter distinctive is that it links the success criteria to formative assessment techniques that enhance these criteria. Specifically, each of the five key strategies will highlight a formative assessment technique, discuss how teachers can use it in the classroom practically, and pinpoint pitfalls (if any) that teachers need to note, for example, as related to classroom management. The aim is to demonstrate how teachers’ simple adjustments to assessment practices can lead to increased classroom participation, learners who are aware of their learning, and typically a more fun classroom experience for all.

It is believed that when teachers are willing to make changes to their current classroom practices regarding formative assessment, in small incremental ways, the learning and teaching experience can be enhanced. These small steps for a teacher can lead to greater learning opportunities for their learners and hopefully, encourage the teacher to venture into more complex formative assessment techniques (Yan et al., 2021). The chapter provides several formative techniques for each of the key strategies that range from the simple, quick, and easily implementable to the more complex techniques that may span over a longer time and require more input from both the teachers and learners. In addition, student/future teachers can also make use of the added resources provided at the end of the chapter.

This chapter can be read in conjunction with the chapter, Formative Assessment For-Of Learning (All Means All).

Key aspects

UNPACKING FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

How do we define formative assessment?

Two evaluation methods that teachers frequently employ to gauge students’ understanding of new content and compliance with learning goals are formative (assessment for/as learning) and summative assessment (assessment of learning). While summative assessment uses the information to determine students’ knowledge level upon the completion of a learning unit or sequence, formative assessment entails obtaining data to improve students’ learning (Dixton & Worell, 2016).

Formative assessment is a continuous, ongoing, and “forming” process that goes alongside teaching. Although there is not a commonly accepted definition in literature, it is widely acknowledged that this type of assessment occurs while teaching and learning are taking place and is considered a crucial component of the instructional process. Interestingly, formative assessment, as mentioned by Dodge (2009), is a part of learning. That is, we cannot regard it as a distinct phase but rather as a key piece of the learning and teaching process.

The main goal of formative assessment is to provide teachers with information on their students’ needs and learning progress during the instructional phase. It is a useful feedback source that empowers teachers with data and gives them a clear picture of their students’ learning journey toward the achievement of the learning goals. In addition, formative assessment can also provide students with information regarding their work and development throughout the lesson. Formative assessment typically has little to do with assigning grades to students. It aims to identify students’ needs in the classroom about the learning goals set by the teacher and the potential areas that need to be improved. Robert Stake’s maxim (Figure 1) describes formative assessment as taking place when a cook tastes the soup and summative assessment when the guests taste the soup. In the first scenario, the objective is to make adjustments while there is still an opportunity to do so, whereas in the second scenario, there is a sense of finality that accompanies the act of judgement (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013).

Figure 1: The difference between formative and summative assessment

There is a wide repertoire of activities, tasks, tools, and resources that can be used in the classroom to implement formative assessment, including observations, exercises, conversations, visualisations, and so on. In the classroom, two types of formative assessment can be implemented: spontaneous (indirect/informal) and planned (direct/formal) (Dixson & Worrell, 2016). Spontaneous formative assessment typically refers to unplanned, unstructured tasks because they require no dedicated instructional time to compile the data for each student and they provide teachers with information about their students’ development. Discussions, body language signs, question-answers during classes, and so on are indicative examples of such tasks. In this way, teachers learn about students’ interests, working styles that appear to help some students or hinder others, subjects or abilities in which some students are very proficient, or areas in which some students are lacking and use this information to plan for upcoming lessons. Planned (direct/formal) formative assessment refers to more structured tasks that are designed to provide information about students’ comprehension and require sacrificing instructional time for the sole goal of collecting data at the student level (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Pretests with paper and pencil, diary entries or writing exercises, quizzes, self and peer assessments, home assignments, and log entries are a few forms of planned assessments.

Formative assessment as an inclusive assessment method

The value of formative assessment in inclusive classrooms cannot be underestimated. Inclusive education aims to ensure equal opportunities for participation in education and learning processes for all students. The primary aim of inclusive pedagogical approaches is to avoid marginalisation in classrooms by applying strategies designed exclusively for specific individual needs (Florian & Beaton, 2018). Using formative assessment strategies provides opportunities whereby students are involved in similar assessment activities which are differentiated for their specific needs. This type of engagement with students can be a driving force to ensure an inclusive learning environment for all students regardless of their diverse needs, levels, and backgrounds.

The question that arises is why employ formative assessment in inclusive classrooms. How can it contribute to inclusion and what can be its impact on teaching in inclusive classrooms? Interestingly, Florian and Beaton (2018) mention that the key assumption for formative assessment is that it supports the engagement of all students in the learning process. In other words, we assume that formative assessment, when used consistently and methodically to enhance all students’ learning and understanding, may contribute to inclusion in classrooms by engaging all learners and teachers in the learning process.

Moreover, by engaging all students in the assessment process, teachers can also encourage them to take responsibility for their own learning, feel independent and included, and improve their metacognition skills and their sense of self-efficacy. Formative assessment can promote self-assessment and guide students to self-monitor their own learning and comprehension. Students may feel more involved in the learning process this way. Furthermore, formative assessment can help students demonstrate what they know, and offer their teachers helpful information so that they can tailor the instruction to their needs (Yan et al., 2021).

In addition, as previously mentioned, by using formative assessment, teachers gain valuable information about students’ needs and progress to adjust their instruction to their students’ needs and leverage their understanding and mastery of the content. This allows them to reflect on their teaching and better organise their instruction to meet the different needs of all students. It is important to highlight at this point that the formative assessment should be aligned with the learning goals to deliver accurate and clear feedback to the engaged learners and teachers. All formative assessment activities and tasks should be designed, pre-organised or spontaneously implemented with the learning goals set regarding the content area of the lesson (Andrade et. al, 2019).

Cizek (2010) provides a list of ten fundamental characteristics of formative assessment that should be considered when designing it.

Formative assessment:

- Focuses on goals that represent valuable educational outcomes with applicability beyond the learning context

- Communicates clear, specific learning goals

- Provides examples of learning goals, including, when relevant, the specific grading criteria or rubrics that will be used to evaluate the student’s work

- Identifies student’s current knowledge/skills and necessary prerequisites for the desired goals

- Requires development of plans for attaining the desired goals

- Includes frequent assessment, including self-assessment, peer assessment, and assessment embedded within learning activities

- Includes feedback that is non-evaluative, specific, timely, related to the learning goals, and provides recommendations to improve

- Encourages students to self-monitor progress toward the learning goals

- Promotes metacognition and reflection by students on their work

- Encourages students to take responsibility for their own learning.

Adapted from Cizek (2010) in Andrade et al. (2019, p. 8)

The aforementioned characteristics illustrate the multifaceted and multi-level opportunities that formative assessment can provide in an inclusive classroom, a classroom that welcomes all students.

HOW CAN WE PUT FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT INTO PRACTICE?

Now that we know what formative assessment is, how do we put it into practice in our classrooms? The next section will provide a step-by-step guide to doing this.

Step 1: Get to know your learners!

All good teaching starts with getting to know your students: knowing about their culture, gender, their well-being, their interests, prior knowledge, language level, organisational skills, the way they learn, etc. Tomlinson (2017) explains these aspects in 3 categories:

- Pre-assessing student readiness

Readiness is about students’ knowledge, understanding, and skills of the content (Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2009). Teachers can learn about students’ prior understanding of the content that the following learning goals will build upon via the pre-assessment of student readiness. Leah, in our example case, can assess her students’ readiness by asking questions, observing the points they find difficult or easy, conducting pretests using pen and paper, writing prompts or journal entries, interviews like think-aloud sessions, using graphic organisers or concept maps, problem sets among others. By assessing students’ readiness, it is possible to spot their misconceptions as well as their knowledge and skill gaps (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013; Tomlinson, Moon & Imbeau, 2015). Students are not blank slates. They might already have some level of knowledge of the new subject, even though teachers have not taught it to them. Due to this, it would be useful for teachers to discover the topics or skills that some students may have already mastered, or possible misconceptions or learning gaps (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Through the assessment of readiness, Leah as a teacher adjusts instruction by designing diverse learning tasks that are adequately challenging for her students’ readiness, allowing them to enhance their knowledge, comprehension, and abilities beyond their current comfort zones (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010).

In addition to assessing students’ readiness to learn new content, a pre-assessment of interests and learning profiles is also important.

2. Pre-assessing for Interests

Students’ interests are the topics or processes that provoke curiosity and inspire passion and, thus, promote attention, facilitate motivation, and encourage the involvement of students (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). In this way, students can connect what is being taught with things they already value. For instance, Leah may choose to differentiate key skills and materials by aligning them with particular students’ interests in several areas, such as music, sports, books, films, etc., which in turn affect motivation, creativity, as well as productivity (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). To make instruction more accessible to more students, it is essential to assess student interest (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Leah as a teacher can make several links between the subject matter she teaches and the interests of her students. For instance, math is easily related to architecture, construction, cooking, and video games. Literature’s themes are clearly visible in history, current affairs, art, and music. Politics, civic engagement, and international cultures are just a few areas where social science can be related. In this way, teachers improve student motivation, achievement, and the relevance of the curriculum.

3. Pre-assessing for Learning Profiles

A learning profile describes how students learn most effectively (Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2009). Students often have various learning preferences, such as different preferences for learning environments, cognitive styles, intelligence preferences, and group orientation (Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006; Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). In this sense, some students may prefer to interact with groups, the whole class, or work alone; in workspaces that are quiet, or with music playing; and/or workspaces with tables instead of desks (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). In addition, some students are visual or kinesthetic learners; others are verbal or auditory learners (Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2009); and another group of students might prefer learning through courses that take multiple intelligences into account (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013).

Leah as a teacher must pre-assess her students’ readiness, interests, and learning profiles because they make it possible for teachers and students to relate new learning to prior information, individualise learning, remind students of essential skills and knowledge, and support their metacognition. Teachers also use this information to change the teaching methods, the learning environment, and the assessment procedures.

For further resources on how to pre-assess your learners, see IRIS | Page 3: Know Your Students (vanderbilt.edu)

Also consult the chapter on Differentiation (All Means All)

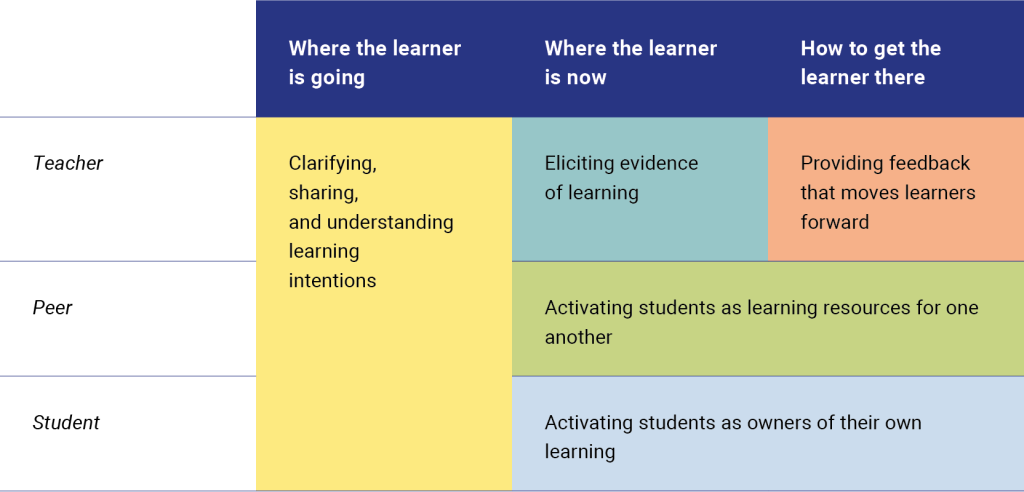

Step 2: Getting to know key formative assessment strategies!

Because every single student has their own individual challenge(s), as teachers we need strategies to assess all students’ learning towards the intended learning outcomes in an efficient way. Thanks to Dylan Wiliams’ work (2018) and others, we have five key Formative Assessment strategies, addressing the earlier mentioned ten characteristics (See sub-heading, How do we define formative assessment? ), which we can use in an inclusive classroom to assess all students’ learning. These strategies incorporate the idea that learning is an ongoing, cyclic process, learners working on goals (feed-up), looking at how far they are towards these goals (feedback) and what next activities should be done to make progress (feed-forward) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

Figure 2: Formative assessment is one cyclic process with three key questions

In general, teachers share learning goals with their learners (feed up) and provide feedback, but sometimes the real feed-forward is missing, implicit, or not clear for learners. However, they should know what to do to successfully complete the task and achieve the learning goal(s). Additionally, when learners are actively involved in this process, it implies that they have more awareness about what and how they learn, which will support their learning. This leads to the five key strategies below, which are all interrelated. Looking at the cyclic character of the five strategies, you can use different techniques in different orders, but keep in mind that the learning intentions and success criteria should always be leading and that your teaching activities and assessment activities are constructively aligned with the intended goals (Biggs, 2006).

Figure 3: Five key strategies of formative assessment

Before we dive into practical formative assessment techniques, we will explain the five key formative assessment strategies and how they are interrelated.

Key Strategy 1: Clarifying, sharing, and understanding learning intentions and success criteria – FEED-UP

Without clear learning intentions, where are we heading to? And if we do not know where to go, how should we assess progress? This seems obvious, but very often students do not know why they should learn something, what quality will be expected, or how to get there. Of course, most teachers will share learning objectives at the start of the lesson, but unfortunately, at that moment they might be meaningless for learners.

Think about how and when to share learning intentions and how to relate them to so-called big ideas, referring to real-life issues and addressing students’ feelings as well. Separate the learning intentions from the context of the activity in order to work on sustainable goals. Discuss what quality will be expected by working with success criteria, related to the learning intentions: key steps or ingredients to be covered to fulfil the task successfully.

Key Strategy 2: Eliciting evidence of learning – FEEDBACK

At different moments, based on learning intentions and success criteria, you would like to know where all learners are in their learning process. For instance, by checking their prior knowledge, checking the impact of your explanation, or halfway through a task. The challenge is to see in one go where all learners are, what progress all learners made, and to engage all learners. This could be done by engineering effective classroom discussions and making use of all-student response systems, digital or non-digital.

Key Strategy 3: Providing feedback that moves learning forward – FEED-FORWARD

Wiliam (2017) states that feedback should be more work for the recipient than the donor because it should cause thinking and not an emotional response. In addition, that feedback should be a recipe for the future. In other words, get learners to think about how to improve their work. To avoid a lack of motivation, there are some ‘rules’ to take into account: limit your feedback, be specific in your feed-forward and praise effort rather than ability, and use comments instead of grades. It is not the summative test yet! Do not forget to provide time to work on it, and check any improvements made.

Key Strategy 4: Activating students as learner resources for each other – FEEDBACK/FEED-FORWARD

As a teacher, you can provide feedback and feed-forward, but for both practical and educational reasons, it makes sense to ask learners to assess their peers’ work, to make them feel responsible for their peers’ and own learning. Bear in mind, that if learners are not used to this way of working, you should teach them how to do this in a safe manner and to engage all of them. This can be done, for instance, by making use of protocols, marking grids, and structured cooperative learning activities.

Key Strategy 5: Activating students as owners of their own learning – FEEDBACK/FEED-FORWARD

Self-regulated learning, metacognition, self-efficacy, and agency are fundamental concepts in education. While these terms may seem complex, simple yet effective techniques can help learners articulate their understanding, identify challenges, and express when they require additional support. Establishing these routines within a safe and structured learning environment creates a foundation for deeper engagement. Once this groundwork is in place, more advanced strategies, such as the use of learning portfolios, can be introduced to further enhance student autonomy and reflective practice.

Step 3: Let’s practice formative assessment!

For each key strategy discussed above, we will now:

- List the main success criteria,

- Provide you with several practical techniques you could use,

- Give examples of how to embed it in an inclusive classroom, and

- Address pitfalls you may encounter when using a particular technique and how to cope with these.

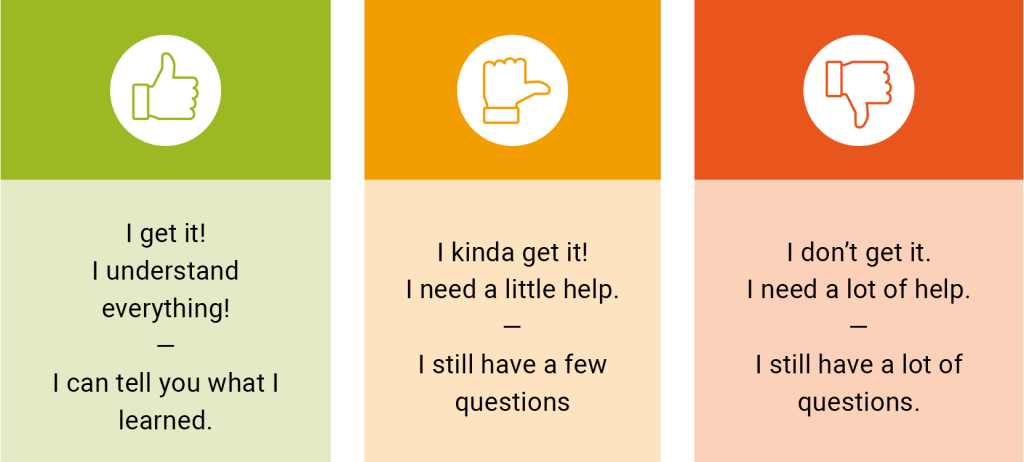

There are a lot of informal techniques you can use in order to check students’ progress and provide information about what to teach next. For instance, thumbs up (I understand), sideways (I may have difficulties in some areas), or thumbs down (I do not understand). There are also more formal techniques, which should be planned in advance and take more time, for example, if you ask students to work on a reading log with the use of a template you created (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). But do not make it too difficult because we know that with simple, small techniques, you can highly impact students’ learning and that ‘the shorter the assessment-interpretation-action cycle becomes, the greater the impact on student achievement’ (Wiliam, 2018, p. 51).

Figure 4: Thumbs check for understanding

All the techniques mentioned can be found on the internet, in Wiliam’s work, as well as other sources, see the list at the end of this chapter.

| Key Strategy 1: Clarifying, sharing, and understanding learning intentions – FEED UP | |

Success criteria:

|

Practical techniques:

|

Example 1

“Leah starts a unit of work about marketing and the role of advertisements. She wants her students to analyse techniques used to seduce people to buy something. Students are tasked to create, in groups of 3-4, a tempting advertisement for a product of their choice.

Instead of immediately sharing the learning intentions and explaining the task, Leah starts off by asking the students which advertisements made them think: ‘I would like to have this!’ and why. Next, she uses the Strengths and Weaknesses Discussion technique that shows her students four different samples of advertisements and asks all students to think individually about which one is the best. Students are then asked to write down at least two arguments to motivate their choice. After a few minutes, the students are told to pair up and compare and contrast their answers. They then come up with the two most important criteria for tempting advertisements, to be written down on two different Post-its. 32 Post-its are then collected on the wall, and the students are invited to walk around and order the Post-its by looking for the same criteria. This leads to a joint list with four success criteria for a high-quality advertisement, with some help from Leah:

- Visuals are used

- Related to the interests of the target group

- Including a quote you will never forget

- Including funny, unexpected elements

After this activity, Leah shares that this unit is about analysing techniques used to seduce people to buy something and asks why it might be important to be aware of how people are manipulated to buy things.

Reflecting on her teaching activity, Leah is happy with the drafted success criteria, but it took her a long time to find good samples of different quality adverts. Fortunately, next year it will be better because then she could ask students to allow her to show their work, of course, anonymously. She also realised that not all students were engaged in the classroom discussion. Some students were so eager to share their experiences that they started yelling and did not listen to the other students. In addition, some students looked distracted and did not come up with any ideas. Also, the final Post-it activity was a bit messy. These are some of the issues that Leah must keep in mind for a smoother classroom activity next time.”

What would you do differently if you were in Leah’s shoes?

If we look at the second formative assessment strategy, we will find techniques promoting all students’ engagement in a classroom discussion, and practical techniques to use to elicit all students’ learning in a structured way.

| Key Strategy 2: Eliciting evidence of learning - FEEDBACK | |

Success criteria:

|

Practical techniques:

Classroom discussion:

All-Student-Response tools:

Digital all response systems

|

Take note: We are aware that not all schools and/or learners have access to digital tools and thus the following example may not be applicable to them.

Example 2

“Reflecting on the Post-it activity, Leah decided to use the digital tool Padlet to make all students’ thinking visible instead of the physical Post-its. Using Padlet, a digital board where all students can upload their Post-its by name or anonymously through the use of nicknames. This avoids students having to walk around, and Leah would be able to move the Post-its to make groups/clusters, which supports her classroom management.

In addition, Leah might use one of the student response systems such as Kahoot, Socrative, Quizzes, Quizlet, etc. to assess her students’ readiness, interests, learning levels and misconceptions through surveys, quizzes, and dialogues. In this way, all her students are part of the classroom conversations and question-answer sections by using their mobile phones and publishing their answers. Through these game-based learning platforms, the motivation and interests of students to learn the topic are increased. Also, her students can examine their conceptual comprehension as well as compare it to that of their peers since they can see how they are doing in comparison to their classmates.

Engaging all students in a classroom discussion might even be more challenging. Leah asked some experienced colleagues how they do this and received different answers. Some of them make use of strict rules, such as asking a question, waiting for a few seconds, and then the students should raise their hand if they want to say something. Other teachers were more inclined to randomly pick students, using the Cold-Calling technique, so that they must pay attention. Leah agrees that this might be good to do but is wondering what to do with students, not really knowing what to say. She decides that in cases like this, she should bounce the question to other students, but will come back to the first one with a question easier to answer. Leah also noticed that she should not pose two questions in one, but that it would be better to start with one, and then ask a follow-up question to the same student or another student.

When Leah applied her ideas in the next lesson during a recap activity, starting with telling students not to raise their hands, they were pretty shocked. Some of them still did, and Leah struggled with being consistent by not rewarding their input and ignoring it. She decided to give it a try for a couple of weeks, realising that both she and her students need time to get used to it, and to make it a routine.”

| Key Strategy 3: Providing feedback that moves learning forward - FEED-FORWARD | |

Success criteria:

|

Practical techniques:

|

Example 3

“Before starting with the final advertisement to be created, Leah asks the groups to submit the set-up of their advertisement: product, target group, and ideas about how to make it attractive and convincing, based on the listed success criteria. She composed heterogeneous groups of 3-4 students with different academic levels and different ways of learning so that they could support each other (Buddy-up technique).

All groups came up with a topic, but the target group for the advert was not always well-defined where some groups were a bit more creative than others. Instead of immediately improving their work or giving ideas, Leah decided that it would be good to add improvement prompts leading to the next step or level. For instance, ‘define who should buy your product’. For one group, struggling with the activity, she gave some examples, making use of scaffolded prompts.

She also noticed that in some groups, one or two students did all the work, whereas some others were not as involved as they should be. Reflecting on this, she intended to make sure that all members of the groups were working in the next lesson. To do this, she needed to figure out what might hinder students from coming up with ideas and materials. Additionally, she thought that it might be good to make use of a cooperative learning activity, structuring group work and addressing students’ individual accountability.

Having nine groups of students with nine products to check in total, it took Leah quite some time to provide proper feed-forward to help students working on creating a good final product. After discussing the main feed-forward plenary, and returning the specific feedback to the groups, Leah asked the students to work on improvements and to show what they had changed. This went well, but Leah noticed that it might be better if the students were tasked with assessing their work and/or that of their peers, which may increase their agency, making them more responsible for their learning. This would also improve her class time management.”

| Key Strategy 4: Activating students as learning resources for one another – FEED BACK/FEED-FORWARD | |

Success criteria:

|

Practical techniques:

|

Example 4

“One lesson later the students drafted their advertisements and Leah decided to organise a peer-feedback/feed-forward activity by asking the groups to pair up twice with another group to compare their work. Aiming for high-quality feedback and feed-forward, Leah first did a recap on the four success criteria with the students, which she stuck on the wall since starting to work on the advertisement task. In her work instruction, she indicates that each group has two minutes to show their advertisement including motivating choices made. After these four minutes, the groups are tasked to discuss in their own groups two things they really appreciate in the advertisement of the other group and one thing that could be improved (Two Stars and a Wish) and then share it with the other group. She tells the students to assign a timekeeper. To increase the quality of the feedback and feed-forward Leah created some sentence starters to be used: “What went well? And better if…”. She re-emphasises that the feedback and feed-forward should be based on the success criteria. For this part of the activity, she planned to spend ten minutes in total.

Before starting it, she asked if all students understood what to do, by using thumbs up (Yes, got it), thumbs sideways (I am not completely sure), and thumbs down (I do not understand yet). Most students indicated that they know how to approach the feedback/feed-forward activity, but some showed that they were not sure yet. She asks some students who put their thumb up to repeat the work instruction in their own words (Say it Better Again) and checks all students’ understanding by randomly picking one student to explain it again.

After the two rounds, the lesson is almost done, and she asks the students to collect their received stars and wishes, to be used for the upcoming lesson. Before leaving, she asks students to individually reflect on the received feedback and feed-forward and to write down one thing they really would like to improve (Exit Ticket). All students submit their exit tickets while leaving the room, with Leah standing in the doorway.

After class, Leah reads all exit tickets and is happy with the planned actions about what to do next. She summarises them and plans to use them at the start of the next lesson. She realises that, thanks to this more structured cooperative learning activity, it was easier to manage the classroom. The only thing Leah is not sure about is how far individual students are in their learning. That makes her decide to conclude the unit of work with an individual activity to assess what students gained from it and make students aware of what they developed and how.”

| Key Strategy 5: Activating students as owners of their own learning – FEEDBACK/FEED-FORWARD | |

Success criteria:

|

Practical techniques:

|

Example 5

“In the next lesson, Leah starts by discussing the results of the exit tickets. Then she tasks the different groups to make a shortlist and to finalise their advertisements in order to submit it to the next lesson. In a classroom discussion, she evaluates with the students what kind of strategies marketers use to seduce people to buy their products. She also asks the students to reflect on working in groups: what helps and what to avoid?

At the end of the lesson, Leah wanted her students to individually reflect on their learning by writing a reading log, but some struggled with how to do this. She consulted Wiliam’s work (2018, p. 184) and found prompts she would like to use:

- In these lessons, I learned…

- I was surprised by…

- What I liked most about this unit of work was…

- The most useful thing I will take from this unit of work is…

- One thing I am not sure about is…

- I would like to learn more about …

- I might have gotten more from this unit of work if…”

HOW CAN YOU GET STARTED WITH FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT IN YOUR CLASS?

What we know from research (Wiliam, 2018) is that formative assessment in itself is not decisive for students’ success, but that the quality of the teacher makes the difference. But what makes a good teacher? Looking at the five key formative assessment strategies, they are all intertwined, which emphasises the holistic character of teaching. Good classroom management and creating a safe learning environment are prerequisites for embedding formative assessment and increasing student learning. On the other hand, this could be seen as a circular process, where using meaningful learning goals, engaging questioning techniques that involve all students, feedback activities that guide students on what to do next, and helping students become aware of how they organise their work and approach learning, will all contribute to supporting classroom management and learning culture.

With more experience and having your own classes it might be easier to work with formative assessment, but one of the benefits of student-teachers is that they are open to trying new techniques and have the time to experiment during micro-teaching activities and their internship. In this way, they might inspire their mentor-teachers and most of all their students.

In addition to this, here are some tips to get started with formative assessment, based primarily on Shirley Clarke’s work (2005):

1. Take your time

Formative assessment is not just about using one tool, it is a way of teaching. Think about where to begin and what steps to take next. Start by sharing learning intentions in a meaningful way, and consider comparing and contrasting different work samples to discuss quality and set success criteria.

- Do not rush

It will take time for both you and your students to get used to new routines. Be patient. - Share your insights

Talk with colleagues, lecturers, and peers. Sharing ideas helps everyone grow. - Learn from the experts

Consult the work of formative assessment experts like Shirley Clarke and Dylan Wiliam. Dive into more readings on the topic, and do not forget to check the references at the end of the chapter for further suggestions. - Keep a journal

Jot down notes about what worked well in lessons, what could be improved, and ideas for making things even better next time. - And most importantly, involve your students!

Ask students for feedback on the formative assessment strategies you’re using. Get their opinions and listen to how they feel about it.

When formative assessment is not part of the routine at your school and everyone is focused on grades and summative tests, it is common for students to say they prefer grades over comments, dislike random questioning, or would rather get feedback from teachers instead of doing detective work or receiving peer feedback. Do not be discouraged. This shows you’re on the right track, encouraging your students to think and engage more deeply. It also highlights the importance of having a school-wide formative assessment policy. Embedding formative assessment into regular practice across classes will support you in making it a part of your teaching. Keep communicating the why, what, and how of formative assessment with your colleagues, school leadership, students, and their families.

Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter is to emphasise the value of formative assessment in inclusive classrooms and to provide alternative paths to put it into practice. Literature review indicates that formative assessment, when employed consistently and continuously, may involve all students and instructors in a safe inclusive classroom environment that fosters equality and equity among its members.

Formative assessment is conceptualised as a dynamic evaluative process that serves two main roles in the ongoing instructional process: it informs students about their understanding of the content and engages them in the learning process, while also acting as a catalyst for teachers’ reflection on their practice and the selection of instructional strategies.

When formative assessment is put into practice, the following elements should be included for its success: clearly laid out learning goals, a variety of formative assessment techniques to elicit students’ learning, and feedback in a range of formats at appropriate levels. The diversity exhibited in the collection of formative assessment techniques reminds us that there can be no one-size-fits-all package (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Getting to know the students, the way they learn better, their academic readiness level, their needs, interests, and background assist in adopting multiple means of formative assessment that offer several evaluation paths to show their understanding. By ensuring the engagement of all students in the assessment and learning process, teachers create fruitful conditions for a safe inclusive environment where none is excluded or feels marginalised. In such a welcoming and safe learning environment, students may be comfortable clearly communicating their mastery of the content, thus providing useful information to teachers about their knowledge level, and any potential gaps or misconceptions.

The chapter highlights a wide range of formative assessment techniques from the conventional to more contemporary, providing teachers with a variety of options to select those they consider appropriate to help students demonstrate what they know. In several of these, technology plays an important and facilitating role.

Continuous training of pre-service or in-service teachers in a variety of assessment strategies and techniques will equip them with the knowledge and the flexibility to create or choose formative assessment techniques that are best suited to their classroom. It is crucial to emphasise at this point that even if a teacher is unfamiliar with all of the approaches presented in this chapter or other works, the process of assessing the current situation starts the moment the teacher enters the classroom, even in a more informal way. As a result, it is critical for teachers to enhance their knowledge of the value of formative assessment in guiding all students’ learning and growth. Typically, practising formative assessment in the classroom leads to a more fun learning experience for your students, and students tend to learn more, remember more, and see the connections to what they are learning more holistically. And who does not want to be a fun teacher doing fun things in their classroom?

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- How can students’ involvement in formative assessment be improved?

- How can specific learning targets relate to students’ future achievement goals?

- How favourable should an educational context be for formative assessment?

- What can be done to enhance the feasibility of assessment for learning?

- What is the importance of clarifying, sharing, and understanding learning intentions and success criteria? How can we do this in a meaningful way engaging all students?

- What makes an effective classroom discussion, eliciting evidence for learning?

- What is the importance of student agency and self-regulated learning?

- How do peer- and self-assessment contribute to student agency and self-regulated learning?

- If independent learning is so important, why does it happen so little?

- How do we balance formative and summative assessment?

Tasks

Activity 1: How to share learning intentions

Think about a topic to teach and how to introduce it, including big ideas, learning intentions and success criteria. Prepare a teaching activity in which you share your learning intentions in an engaging way and work with success criteria, related to a task for students. Teaching time depends on your activity, so do not rush yourself. Include ideas about what to take into account regarding how to manage the classroom.

Success criteria to consider:

- At least 3 learning intentions are formulated by making use of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom verbs).

- Learning intentions are connected to a big idea, related to a task, and by keeping the context of learning out of the learning intention.

- At least 4 success criteria are provided, giving clear steps or ingredients indicating how to successfully finalise the task.

- Learning intentions and success criteria are shared with students in a creative way, stimulating all students’ learning.

- Ideas about classroom management are included.

Activity 2: How to engineer a classroom discussion

A classroom discussion is meant to inspire all students to deepen their knowledge and develop their thinking skills about a specific topic. It is often used to introduce new materials but has to be built on expected prior knowledge, which explains its use as a formative assessment technique eliciting students’ prior knowledge. The teacher guides the discussion but is not involved in answering the questions themselves. Students need to be active, which emphasises the teacher’s use of effective questioning skills and efficient all-response systems. Think about a topic to discuss and how to organise your classroom discussion.

Success criteria to consider:

- The discussion lasts 10 -15 minutes .

- Prior knowledge of the students, related to learning objective(s), is elicited

- Questioning strategies are used in order to make all students think, i.e. wait time, no hands up, no opt out, etc.

- A range of different questions are used. They are at the right level, not only checking understanding, but to make visible what to teach next.

- Students are encouraged to develop their own questions and to ask them to the teacher as well as to peer students.

- At least one all-response system is used.

- Classroom lay-out is in line with the activity and motivated with reference to relevant theory.

- Classroom discussion procedure is announced to the students.

Activity 3: Providing feedback and feed-forward

Dylan Wiliam (2015) states: ‘Feedback should be more work for the recipient than the donor’. Explain the meaning of this statement and provide three concrete examples, related to your serial lessons, of how to organise feedback that is “more work for the recipient than the donor” and offers clear guidance on what to do next.

Activity 4: Peer assessment

Working on their task (accompanied by success criteria), organise a peer assessment activity, in groups of 3-4 students.

Consider the following:

- Describe the peer assessment activity you plan to organise and explain your rationale for choosing it.

- How do you prepare your students for this activity and what do you tell them before starting?

- Explain how you will create groups: homogeneous groups or mixed-ability groups. Give reasons for your answer with reference to relevant theory.

- Explain the importance of ‘individual accountability’ and how to safeguard it within your activity.

Activity 5: Self Assessment

Watch the video (5.46 minutes) about Self-Assessment and provide ideas about this strategy in this chapter.

Link to the video: Self-Assessment: Reflections from Students and Teachers – YouTube

Answer the questions below and share your ideas with a peer:

- What connections do you draw between the video and the text and your own life or other learning?

- What ideas, positions or assumptions do you want to challenge or argue within the video and the text?

- What key concepts or ideas do you think are important and worth holding on to from the video and text?

- What changes in attitudes, thinking, or action are suggested by the video and text, either for you or others?

(Based on The 4 C’s Thinking Routine (The 4 Cs_1.pdf (harvard.edu)

INTERESTING VIDEOS

1. Dylan Wiliam – The Classroom Experiment

The Classroom Experiment (episode 1): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J25d9aC1GZA

The Classroom Experiment (episode 2): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1iD6Zadhg4M

Short version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0TTgeSn7ys

In this BBC documentary Dylan Wiliam works with a school on implementing formative assessment techniques, such as no hands up, mini whiteboard and traffic lights. The full documentary lasts 2 hours, but you can also watch the short version of it.

2. John Hattie about Learning Intentions and Success Criteria

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvzeou_u2hM

This is a short video on how to make learning visible, discussing the high impact of sharing learning intentions and success criteria with students.

3. Austin’s Butterfly

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_6PskE3zfQ

This is a short video on how to discuss high-quality work, providing feedback and feed-forward and showing that practising really works to improve students’ work.

4. Peer-assessment: Reflections from Students and Teachers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqWCJZH8ziQ

This is a short video about how to put peer assessment into practice.

5. Self-assessment: Reflections from Students and Teachers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CkFWbC91PXQ

This is a short video about how to put self-assessment into practice.

6. Shirley Clarke: Formative assessment into practice

https://www.shirleyclarke-education.org/videos/

Six free short videos about different formative assessment techniques in action.

CONNECTED CHAPTERS

This chapter can be read in conjunction with the following chapters in the All Means All Book:

*Formative Assessment for/of Learning

*School Assessment in an inclusive education system – Do we measure what we value or do we value what we can measure?

*Differentiation