Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

Navigating Horizontal Transitions: Building Participation and Support for Young Learners and Families in Educational and Community Settings

Chris Carstens; Francesca Mara Santangelo; and Nariko Hashida

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Let us start by reading about this experience of a horizontal transition and the development of an educational network that took place in southern Italy.

“Three years ago, I worked with a boy who had severe behavioural difficulties and a total lack of control over his emotions. As you may know, the Italian school year begins in September. From September to December, this boy had four special needs teachers, each of whom shortly thereafter abandoned their position due to the difficulties of managing the child, his aggression, and other behavioural issues. One day, the last support teacher to arrive called me because she had known me for some time, and they were desperate at the school. I went to the school and met this boy, his teachers, and his classmates. He was eight years old at the time and was as tall as me. I had a fun and creative time with them at school. My initial goal was to build a relationship with the young learner and gain mutual trust. This is because I strongly believe that in any educational and care relationship, the person must be placed at the centre, with the resources revolving around them in a harmonious manner and in dialogue.

Around the young learner, we built a network made up of the family, the school director, the teachers, me as a pedagogist, the psychologist, the neuropsychiatrist, and the managers of two social communities responsible for designing personalised educational and health interventions through laboratory and occupational activities.

For all of us, the first step was to identify the most important need of the child and his family. In Italy, we have a very important official document, namely the community educational pact, drawn up by all the actors involved in an educational project: the family, school staff, therapists, and the rehabilitation and educational associations or communities involved. Within these agreements are the educational objectives that are intended to be achieved for the well-being of a young learner and their family.

In our case, we identified the actors involved and defined not only their roles but also the spaces and times to develop the educational project for this child. After several conversations with the young learner and his parents, we came to define his educational project, of which I’m going to list only the most important features.

Political institutions made a free transport service available to the family, responsible for accompanying the child to various places during his day: school, the rehabilitation centre, the headquarters of an association, and finally home. Together with the head teacher, the parents, and the health facility managers, we decided that the young learner would spend 3 to 4 hours at school with his classmates, carrying out normal teaching activities with the support of a special needs teacher in the classroom. Then, he would be taken to the rehabilitation centre, where he could participate in therapeutic activities to improve his behaviour and gain emotional control. Before returning home, on some days of the week, he would take part in educational and recreational projects with other peers at the school or at the headquarters of other associations.

Over time, the results highlighted a reduced stress load for the family, who, having other children, were unable to manage the entire situation, including the necessary travel. Even more importantly, the therapeutic objectives achieved allowed for more peaceful teaching activities in the classroom, better family management, and a greater sense of well-being for the young learner, who never lost contact with his classmates and peers and was able to benefit from a strong support system created with and for him.”

Initial questions

In this chapter, you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What does horizontal transition mean, and what situations does it include?

- What are the barriers to building an educational network for horizontal transitions?

- How do horizontal transitions between different educational settings (e.g., public to private schools, or between different school districts) affect young learners’ performance and their social and emotional well-being?

- What are the primary challenges faced by schools and educators in managing horizontal transitions, and how can these challenges be mitigated?

- What strategies and support systems are most effective in facilitating successful horizontal transitions for young learners?

Introduction to Topic

Horizontal transitions in education refer to the changes young learners’ experience within the same level of education, such as moving between schools, shifting from one classroom to another, or transitioning between educational programs. Unlike vertical transitions, which follow a clear progression from one life stage to the next (e.g., moving from primary school to secondary school), horizontal transitions occur when young learners move across similar educational environments. These shifts can result from various circumstances, such as family relocations, changes in educational needs, or placement in specialised programs.

It is essential to remember that not all individuals experience a wide range of horizontal transitions, and the types and impacts of these transitions can vary significantly. For some, horizontal transitions may be infrequent or limited to a single shift between schools or classrooms. Others may face multiple transitions in a short period, each requiring them to adapt to different social, academic, and environmental factors. For instance, while one young learner might transition from a mainstream to a specialised program within the same school, another might shift between multiple schools due to frequent relocations, each time confronting new routines, peer groups, and expectations.

These transitions are often complex and layered, as they require learners to adjust to new surroundings, teaching styles, peer dynamics, and support systems—all while trying to maintain academic progress and emotional stability. For vulnerable young learners—such as those with disabilities, learning difficulties, or emotional and psychological challenges—horizontal transitions can be particularly demanding. The unfamiliarity of each new setting may heighten anxiety, disrupt learning continuity, and amplify feelings of isolation or instability. For such young learners, additional resources, personalised support, and careful planning are crucial to ensure they continue to thrive in their new environment.

Furthermore, the nature of these transitions varies not only across individuals but also within different educational or cultural contexts. For example, an adult refugee moving between countries due to political or economic instability may experience horizontal transitions that are more radical than those within a single country or educational system. A young learner with a disability may need to transfer between mainstream education and a rehabilitation or specialised educational community, each with distinct support structures and expectations. Recognising these variations in horizontal transitions underscores the importance of personalised planning that is responsive to each individual’s unique needs and circumstances.

Effective management of horizontal transitions is vital for minimising disruption and promoting continuity in a young learner’s education. Schools and educational institutions play a key role in facilitating these transitions by creating supportive, inclusive environments and by coordinating efforts among educators, families, and specialised services to meet each learner’s specific needs. Addressing the emotional, social, and academic aspects of these transitions is essential to help young learners feel secure, resilient, and empowered in their new settings.

As you read through this chapter, keep in mind that each learner’s experience with horizontal transitions is distinct, shaped by their personal, social, and educational context. Developing an awareness of the diverse ways these transitions manifest will enhance your understanding of how to create effective, tailored support plans that enable learners to adjust smoothly and maintain their educational progress.

Key aspects

Definition

Understanding transitions requires recognizing the multiple layers influencing a learner’s experience, as outlined in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model. This model emphasises that a young learner’s ability to adapt is shaped by immediate settings, such as family, peers, and school, as well as by the interactions between these groups. Beyond these, broader societal factors—including policies, cultural norms, and the availability of resources—further impact transitions. By acknowledging these layers, educators and stakeholders can better identify the barriers that may hinder a young learner’s adjustment, as well as the support structures that can help them succeed. This holistic perspective sets the stage for creating educational environments that foster smoother, more supportive transitions for all learners (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

We can distinguish between two types of transitions: vertical and horizontal. Vertical transitions refer to the major chronological events in life, such as progressing from birth, to nursery, to primary school, and eventually entering the workforce and retirement. These transitions, mapped on a vertical axis, reflect the stages everyone passes through. However, comprehensive planning for these transitions is often lacking (Ginger & Patton, 1996).

Horizontal transitions are less visible than vertical transitions and occur frequently. They refer to the everyday moves that children (or any person) make in different parts of their lives, such as going from home to school or from one care setting to another (Cappello, Ferrel, Pallokosta, and Iturria, 2023). In other words, all those things happening on the same temporal plane, placed precisely on a horizontal axis. Such transitions could be, for example, the transition from public schools to private schools, a transfer to different school districts, or a change in educational programs within the same institution. These transitions are common due to various factors such as family relocations, academic demands, or personal preferences. However, the implications of these transitions on young learners’ academic achievement and social and emotional well-being are profound and multifaceted. Understanding the challenges and opportunities presented by horizontal transitions is critical for educators, policymakers, and parents.

Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model as a lens, these transitions reveal how support structures at different ecological levels—family, school, peer groups, and the broader community—impact the young learner’s ability to adjust. For instance, vertical transitions may demand strong institutional support and curriculum alignment to bridge educational gaps. Horizontal transitions often depend on more immediate support systems, like consistent peer and teacher relationships, to create stability and continuity in the learner’s educational and social experience. This figure underscores the importance of tailored support systems that respond to the specific nature of each transition, helping young learners with special needs navigate new environments and maintain their well-being.

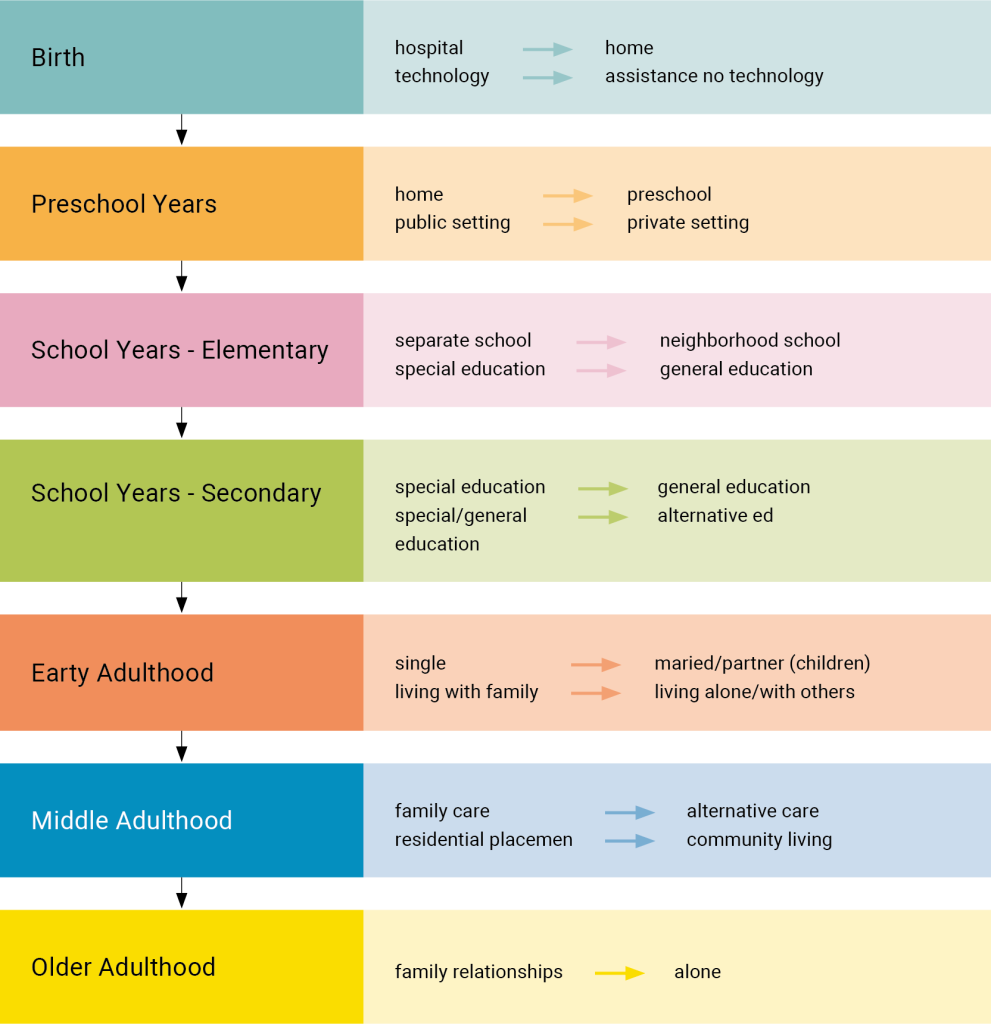

Figure 1: Vertical and select horizontal transitions. Note. From Transition From School to Adult Life for Students with Special Needs: Basic Concepts and Recommended Practices

The figure above illustrates both vertical and horizontal transitions specifically for young learners with special needs. Vertical transitions, shown as milestones like progressing from primary to secondary school, signify shifts to new educational stages with increased expectations and challenges. Horizontal transitions, in contrast, represent moves within the same educational level, such as transferring between special education programs or changing schools due to family relocation.

One of the most important and frequently discussed horizontal transitions is the movement from separate settings to less restrictive, more inclusive ones (Ginger and Patton, op. cit.). Moving from segregated to more inclusive settings is important for the horizontal transition of people with disabilities. Figure 1 highlights several such transitions for individuals with disabilities from a chronological perspective.

The need for transitions into inclusive communities, though not always labelled as “horizontal transitions,” has been a topic of discussion since the 1980s. Fish (1986) argued that the objectives of these transitions should be the same for everyone, regardless of disability. He identified four key, interrelated objectives for successful transitions:

- Employment, useful work, and valued activity

- Personal autonomy, independence, and adult status

- Social interaction, community participation, leisure, and recreation

- Roles within the family

The objective of social interaction, community participation, leisure, and recreation highlights that greater community involvement can promote increased personal autonomy, independence, and shifts in family roles and relationships. In essence, participation in a more inclusive society can foster greater independence and autonomy for learners with disabilities or other needs, ultimately transforming their relationships and helping them achieve personal and social milestones.

Throughout this chapter, we will analyse the process of horizontal transitions, starting with the framework of Schlossberg’s theory and identifying four key concepts that, in our opinion, outline the fundamental aspects of a horizontal transition.

Schlossberg’s Transition Theory

Schlossberg’s transition theory, named after Nancy Schlossberg, professor emerita of counselling psychology at the University of Maryland, can be really helpful in understanding not only what transitions are but also how people experience change and what could help them cope well with this process.

Whatever type of transition we are discussing, they tend to exist on a continuum, so they can be formal or informal. For example, it could be leaving one school to move to another. It could be planned. It could be something that was planned for two years and then gradually happens. Or it could be completely unplanned. This could be someone having to flee one country to move to another or transitioning between occupations. As we can already imagine, some of these transitions may be easy, while others are exceptionally difficult.

The theory was developed by Schlossberg, who conducted research on a group of adults who had been unexpectedly fired from their jobs. Suddenly facing unemployment and an unplanned transition, these individuals responded to the situation in different ways. Schlossberg was curious to understand why some people were able to navigate this transition positively, achieving favourable outcomes, while others struggled. Originally, the theory was part of research on adult development, designed to help understand and manage life transitions as part of the “ordinary and extraordinary process of living” (Evans, Forney, Guido, Patton, & Renn, 2010). Over time, it has become a guiding framework for understanding and explaining horizontal transitions in other life phases, beyond just adulthood.

Referring to Schlossberg’s theory to understand and intervene in a transitive process, understood by the authors as “any event or non-event that translates into a change in relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles,” we can outline it as follows (Anderson, Goodman, and Schlossberg, 2012):

A. Look carefully at the transition

a) Identify the type. Schlossberg’s theory identifies three: anticipated – refers to foreseen events, unexpected – refers to sudden and unplanned transitions, non-events – concerns events that should have occurred but did not take place.

b) Clarify the context – the circumstances in which the transition occurs.

c) Evaluate the impact – the reactions that arise from a specific transition.

B. Create the resources framework

The theoretical model identifies the so-called 4 S, i.e. four main factors that influence a person’s ability to face a transition. These factors are:

a) Situation – the context in which we find ourselves: what are you starting from? What or where are you moving towards?

b) Self – personal resources: who are we? What kind of psychological resources do we have? What are our prospects? What is our perspective or what values do we have?

c) Strategies – how we deal with events in our lives, especially unexpected ones? It is a fact that we all go through transitions throughout our lives. But what are our strategies when we discover that something stressful is happening? Do we deal with the situation by avoiding it or pretending it’s not happening?

d) Support – external resources: what support do we receive from family or people in our networks? Having relationships that generate support and support plays a fundamental role in transitions, as it represents a protective factor against the risk of negatively facing a sudden event and experiencing situations of marginality, social isolation and vulnerability.

C. Strengthen resources and intervention

The resources available during a transition can either provide opportunities for growth and improvement or, conversely, lead to decline. According to Goodman et al. (2006), transitions can be broken down into three phases:

- Moving in: This represents the moment in which you learn the characteristics of the new situation, including the rules, expectations, and new roles.

- Moving through: This is about finding balance in the new dimension of life.

- Moving out: This represents the end of the transition process and the continuation of life, awaiting new transitions.

In this process, the person will face the transition in a positive, neutral, or negative way, based on the resources they have available. Regarding the first “S” (Situation), key factors include the nature of the event, its timing and duration, the level of control the person has over the situation, changes in their role, and any simultaneous sources of stress. The second “S” (Self) refers to how personal attributes—such as age, gender, cultural background, socio-economic status, health, values, beliefs, ego, resilience, and psychological resources—affect how someone navigates a transition. The third “S” (Strategies) involves developing flexible and varied action plans, which offer a wider range of responses to challenging events. This includes coping strategies, the ability to adapt and adjust, and the capacity to manage stress while maintaining a focus on self-care and well-being. Finally, the fourth “S” (Support networks) comprising emotional connections with family, friends, intimate relationships, institutions, and other community resources, are crucial in creating a protective environment around the individual during times of transition.

Barriers to horizontal transitions

Transitioning to a new educational environment often requires young learners to adapt to a curriculum with different levels of progression and difficulty and to form relationships with new peers, teachers, and staff. Young learners are expected to navigate these significant changes in a short period, but not all young learners experience a smooth horizontal transition. This section discusses possible barriers to horizontal transitions between schools or education systems at the same level.

Differences in curriculum

It is well known that the vertical transition between primary and secondary school is often challenging. Hanewald notes that during the transition from primary to secondary school, young people move from small, self-contained classrooms to larger, more heterogeneous schools with increased expectations of independent academic performance and less teacher support (Hanewald, 2013). Galton et al. suggest that around 40% of pupils experience a hiatus in progress during vertical transitions, particularly when moving from primary to secondary school, due to a lack of curriculum continuity between these educational stages (Galton et al., 2000).

However, this type of difficulty can also arise during horizontal transitions between schools or programs at the same level of education. Higher levels of school mobility are associated with lower academic performance, more emotional or behavioural problems, and greater difficulties with social adjustment (Snozzi et al., 2024). As this type of transition is not necessarily experienced by many young learners, little attention has been paid to the issue.

Young learners experience horizontal transitions and difficulties in different ways, even within the same stage of education. Slightly higher rates of young learner mobility are reported for young learners with special educational needs (SEN) than for young learners without SEN, and mobility appears to be particularly high for young learners with emotional disturbance (Snozzi et al., 2024).

When a young learner with SEN moves from a special education program (school or class) to a mainstream program (school or class), the young learner may find it difficult to adapt to the faster paced and more advanced curriculum. Demetriou et al. explain the decline in motivation in terms of a loss of self-esteem in a larger and more overtly competitive environment (Demetriou et al., 2000). Conversely, young learners moving from mainstream to special classes may find the content too easy and unengaging (Tsutsumi 2019), leading to decreased motivation to learn. Thus, differences in content and learning levels resulting from school transfers can reduce motivation and hinder young learners’ ability to learn in a new environment.

Furthermore, migrant and refugee young learners attending schools in different countries need to study subjects through a foreign language other than their mother tongue. Japanese research suggests that acquiring a foreign language as a language of study takes longer than learning it as a language of life (Kinnan 2024). This presents unique difficulties for migrant and refugee young learners, extending beyond mere academic catch-up and impacting their overall learning progress.

Changing relationships

As Spernes’ review shows, the transition from primary to secondary school may elicit social and emotional challenges for young learners (Spernes, 2020). Traditionally, schools have facilitated a smoother transition from primary to secondary school by ensuring that pupils move to the new school or class with at least one good friend (Demetriou et al., 2000). Having a peer helps young learners meet their social needs for familiarity and companionship in the “big school,” easing some of the anxieties that come with the transition (ibid). As Blatchford (1998) points out, “friendships can help reduce uncertainty and thus facilitate adjustment to school.” Additionally, a positive relationship with teachers plays a key role in promoting young learners’ commitment to learning. When a young learner moves to another country or state or switches to a different educational program, maintaining previous friendships and relationships with staff becomes increasingly challenging. They must rebuild relationships with others in a new community. However, migrant or refugee young learners may face additional barriers, such as limited proficiency in the local language, hindering their ability to connect with their peers.

Additionally, some teachers and young learners at the new school may view new young learners as ‘newcomers’ and struggle to empathise with their feelings. Demetriou et al. describes a ‘good teacher’ for young people as someone who consults them, who is fair, who makes them feel important, and who treats them in an respectful way (Demetriou et al., 2000). To facilitate a smooth transition, it is necessary to support both young learners and teachers in the new school to cultivate positive relationships.

Schools, classrooms and communities that exclude diversity: Barriers and reasons for horizontal transition

Traditionally, schools and classrooms have played a role in perpetuating and reinforcing homogeneity, often at the expense of valuing diversity. Therefore, children who belong to a minority group are more likely to face exclusion due to their perceived ‘differences’. International research has emphasised the exclusion and bullying experienced by vulnerable children, including those with disabilities, refugees, and children affected by migration (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017).

Considering that positive relationships between children can influence their academic performance, there is concern that excluded and bullied children may underachieve. Furthermore, poorer performance or difficulties in adjustment may lead to children being placed in segregated educational settings, such as special classes and schools. The over-representation of children from migrant backgrounds, as well as children with disabilities, in special education is also believed to be linked to the high level of exclusivity in mainstream education (Kinnan, 2024).

Therefore, inclusive schools and classrooms that recognize and embrace diversity and do not exclude children from different cultural and social backgrounds, are essential. Holistic school programs to prevent bullying are often successful, and in several countries, it is a legal requirement for schools to have an anti-bullying policy (Menesini and Salmivalli, 2017). In schools in England, disability equality training has been led by disability organisations to eliminate bullying of children with disabilities and promote diversity inclusion (Hashida 2024).

Difficulties in sharing information and coordination

When young learners transition between schools or education systems, seamless coordination and information sharing between the local education authorities, schools, families, and young learners are crucial.

Teachers and coordinators at the previous school are familiar with their young learners’ learning achievements, special educational needs, and social dynamics, such as how they relate to their friends. Sharing such information enables teachers at the new school to effectively support the learning and relationships of transferred young learners. This requires developing systems to share data on young learners’ learning, friendships, and support needs. If the previous and new schools fall under the same inter-municipal authority, communication and information sharing are relatively easy. However, when young learners move to schools in a different country or region, communicating and information sharing become significantly more challenging.

Even when information is shared, there is no guarantee that the new school can offer the same learning content. In England, for example, the introduction of the National Curriculum was intended to ensure continuity and coherence of learning across schools. However, Galton et al. found that in spite of this curriculum framework, there were still serious discrepancies between the work pupils were given before and after the transition from primary to secondary school. Their research in the English education system shows that these gaps in curriculum alignment can significantly disrupt young learners’ progress during this key educational transition (Galton et al., 2000).

Moreover, young learners with special educational needs may not receive the same level and quality of support in their new school due to potential differences in inclusion policies, staffing structures, and teacher attitudes between schools. These difficulties in information sharing and coordination can disrupt the smooth transition of young learners to their new school or educational program. Snozzi et al. said that if a young learner transferred from a special class to a mainstream class, it could be determined that the young learner received SEN support in the special class, but there was no information in the data about whether the young learner continued to receive SEN support after the transition (Snozzi et al., 2024).

Collaborative strategies and support systems for successful horizontal transitions

Effective strategies and support systems are essential for ensuring successful horizontal transitions, such as moving between schools or educational programs. Addressing not only academic but also social and emotional needs is critical to helping young learners adjust. Collaboration between teachers, peers, families, and the wider community plays a key role in this process. Strong communication among all parties ensures that personalised support is in place, while peer and teacher relationships provide young learners with a sense of belonging and stability. Family and community involvement further reinforces these support networks, helping to create an inclusive environment where young learners can confidently navigate their transitions and thrive.

Collaboration and communication

Collaboration and communication are key components in managing horizontal transitions within the educational system. Effective collaboration and communication between various stakeholders – including young learners, teachers, parents, and administrators – can significantly impact how well young learners adjust to these transitions, ensuring both their academic progress and emotional well-being.

Let us read this example case from Germany:

Germany is reputed to be extremely bureaucratic and any kind of legal procedure involves a large amount of paperwork going backwards and forwards. Even though the standard procedure requires mandatory meetingsconcerning childrens’ welfare or educational paths, these rarely involve authentic communication between participants or with children and their respective families. Because of this we often lack transparency and real human connection. A school I used to work at for example was in an area which had extremely high rates of crime and poverty which occasionally made it necessary for us to report certain incidents, seek assistance or even relocate children if their home environment was deemed unsafe. Despite this the school had a notoriously bad relationship with Child Protective Services (CPS), which made collaborating almost impossible. Mails went unanswered, appointments were denied and any kind of feedback concerning the young learners who needed assistance was non-existent. Case workers would simply show up in my classroom unannounced and try to arrest young learners in order to take them to a general holding facility – this was both traumatic and catastrophic considering school needs to be a safe environment for everyone. I used to have a huge problem with that, until one day we wanted to take a young girl into care because there was a very dramatic situation in her home, and it was clear she would not be able to return.

First of all, I sat down with the girl and I explained to her what the situation was and how the procedure worked so that she would understand exactly what the next steps would be. Transparency and predictability are extremely important in such stressful and traumatic situations. She had her bag packed beforehand and we discussed the phone call she and I would now have to make. We were optimistic because we had planned this transition in advance and had selected a lovely foster family who knew the girl in advance and was willing to take her in. In my eyes it was the best you could have made out of a drastic situation. But CPS does not work that way in Germany. You basically have to call a hotline and you do not know who is going to pick up the phone, and it is more than likely that they will simply take over the case without any further collaboration or planning. That usually ends up in the child being taken to a general holding facility until further evaluation. I had to explain this to the girl, because I think it is very important to prepare them for all the possible scenarios, so that they can brace themselves. In this case, luckily enough, a gentleman whom I had not met before, picked up the phone and was extremely laid back and helpful when I explained the situation and our ideas to him. He agreed to let me take the girl to the foster family in my own car and met us there to evaluate and assess the situation on the same afternoon. We actually sat outside in the family’s garden and had coffee and cake, and the girl got to explain her situation and the case worker got to know everybody and wrote his respective report. This was the smoothest transition and the most ideal outcome for a very dramatic situation.

Additionally this turned out to be a very fruitful development for my collaboration with CPS because over coffee I got to explain the troubles our school had been having with their institution and how I wished it could be different. From that we struck up a kind of friendship and started meeting on a regular basis to discuss cases, ideas or just vent about everyday work problems. Meanwhile we have included many others in our meetings, organiseworkshops together and have formed a very constructive and supportive network which transcends school and CPS themselves. I now have an insight into who the people on the other end of the paper trail are and what their work schedule looks like. Our regular meetings have broken down barriers and helped form trust and an authentic human connection in order for us to successfully work together.

The role of collaboration in horizontal transitions

Collaboration among educators, young learners, and families is essential in facilitating smooth horizontal transitions. When teachers and school staff work together to coordinate young learner transitions, it reduces academic disruptions and ensures continuity in learning. This collaboration often involves sharing information about a young learner’s learning needs, academic progress, and social-emotional status to ensure that the receiving teacher or school is well-prepared to support the young learner.

Collaborative strategies such as team meetings, joint planning sessions, and professional development programs allow educators to align their practices and expectations. This is especially critical in transitions involving diverse learning needs, such as young learners with disabilities or English language learners. For instance, ensuring that there is sufficient planning beforehand such as the US model of Individualised Education Plans (IEPs) or that language acquisition programs are seamlessly implemented across different schools or classrooms requires close coordination between educators and specialists (Willis, Doutre, Jacobsen, 2019).

Additionally, collaboration between schools and outside organisations, such as community centres or after-school programs, can enhance the support provided to young learners during transitions. These partnerships often provide additional resources, such as tutoring or mentoring, which can help young learners adapt to new learning environments more successfully (Graham et al., 2022).

Communication as a critical factor

Open, consistent communication is critical in ensuring successful horizontal transitions. When communication between schools, families, and young learners is strong, it promotes transparency, reduces anxiety, and allows for proactive problem-solving. One key aspect of effective communication is providing clear, timely information about the transition process, expectations, and available resources. Studies show that when families are well-informed about what to expect during a transition, they are better able to support their children, helping them feel more confident and prepared (Harper, 2016).

Teachers and administrators must maintain ongoing dialogue with young learners to understand their concerns and ensure that they feel supported throughout the transition. This may involve regular check-ins, feedback sessions, and creating a culture where young learners feel comfortable expressing their challenges and needs. Open communication between young learners and educators helps identify potential issues early, allowing for timely interventions that address both academic and social-emotional challenges.

Parent and teacher communication is another vital element of successful transitions. When teachers engage with families and actively involve them in the transition process, young learners benefit from a more cohesive support system. This is especially important when young learners are transitioning between different learning formats, such as in-person to online learning, as families play a more active role in facilitating their children’s learning in virtual settings. Communication tools such as parent-teacher conferences, newsletters, and digital platforms can help connect home and school, making sure that families stay informed and involved.

Collaborative models for successful transitions

Schools that implement structured collaborative and communication frameworks see more successful transitions. For example, multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) integrate both academic and social-emotional support strategies through collaboration among teachers, counsellors, and administrators. These systems use data-driven decision-making to monitor young learner progress and adapt interventions to meet individual needs (McIntosh & Goodman, 2016).

Similarly, teacher collaboration networks, where educators from different schools or departments share best practices and strategies for supporting young learners during transitions, have been shown to enhance the overall effectiveness of the transition process. As Hargreaves (1999) emphasises, simply working alongside one another is insufficient; genuine collaboration and open dialogue are crucial. Meaningful collaboration and collegiality are key to fostering educational change. Collaboration and communication are essential to managing horizontal transitions in the educational system. Through collaborative efforts among educators, families, and communities, young learners can experience smoother transitions with minimal disruption to their learning and emotional well-being. Effective communication ensures that all stakeholders are well-informed and engaged in supporting the young learner’s adjustment to new learning environments. By fostering these connections, educational systems can better meet the needs of young learners and create a more inclusive and supportive transition process.

Social and emotional support

Social and emotional support during horizontal transitions can play an important role in how young learners adjust to new environments and maintain their academic performance. Additionally, emotional support systems help develop resilience, supporting young learners to cope with the challenges of transitioning without feeling isolated or overwhelmed.

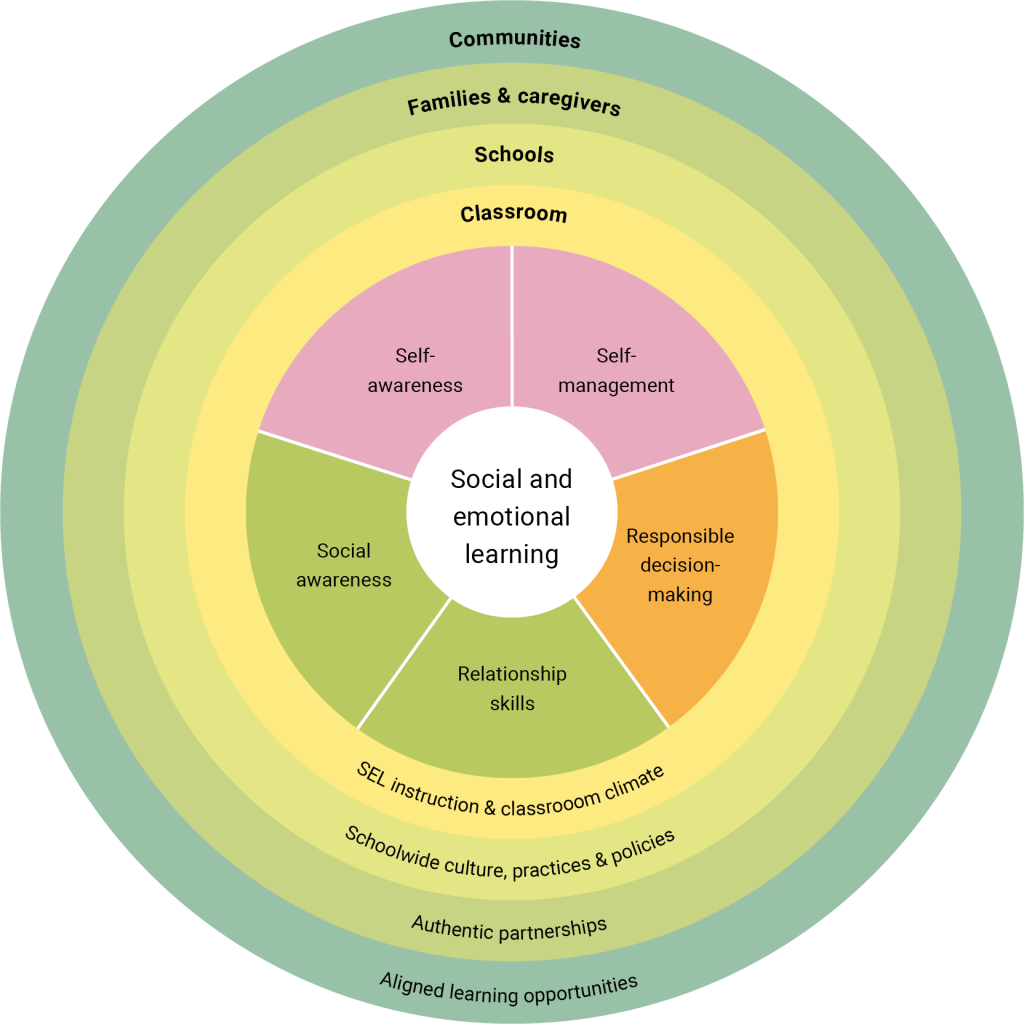

Support systems that focus on social and emotional well-being can reduce the potential for disconnection, which often leads to academic decline or disengagement from school. According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), incorporating emotional learning strategies into school environments helps young learners develop crucial skills such as self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness, which are essential during transitions.

Figure 2: The CASEL Social and Emotional Learning Framework

Peer and Teacher Support

One of the most effective forms of social support in educational transitions is peer support. Peer relationships offer a sense of belonging and shared experiences that can ease the stress of new environments. Peer mentoring programs, for instance, have been shown to positively impact young learners who are transitioning by providing them with role models and a peer network that can answer questions, offer guidance, and create social bonds (Stapley et al., 2022).

Teachers also play a key role in creating an emotionally supportive environment. When educators are attentive to the emotional needs of young learners during a transition, they can create a sense of security and stability. Teachers who prioritise social-emotional learning (SEL) in their classrooms can help young learners manage their emotions, build healthy relationships, and stay engaged with their studies despite the changes in their environment (Jones & Kahn, 2018).

Family and community involvement

In addition to support from peers and educators, family involvement is a significant source of emotional security for young learners navigating horizontal transitions. When families are actively engaged in the transition process – communicating with teachers, offering reassurance, and maintaining open lines of communication – young learners are more likely to feel supported both at home and at school. Research by Eden et al. (2024) shows that young learners whose families are involved in their education tend to exhibit higher academic achievement and better emotional adjustment during transitions.

Communities also play a role in supporting young learners during transitions. Community-based programs, such as after-school activities, provide young learners with additional opportunities to build social connections and access emotional support networks, further buffering the potential stress of transitioning between schools or learning formats (Mahoney et al., 2005). Social and emotional support is a vital component in ensuring that horizontal transitions in the educational system are smooth and successful for young learners. Through the combined efforts of peers, teachers, families, and communities, young learners can develop the emotional resilience and social connections needed to thrive in new learning environments. Without adequate support, transitions may lead to feelings of isolation, anxiety, or disengagement. However, when properly supported, young learners are more likely to experience positive academic and emotional outcomes, ensuring long-term success in their educational journey.

6. Participation and learner-centred approaches

A young learner-centred approach recognizes that each young learner is unique and gives priority to young learners’ needs, interests and experiences rather than strictly adhering to a standardised, one-size-fits-all, teacher-led model. This approach helps to welcome individual differences as a source of richness and as a starting point for teaching and educational action, considering that within this diversity young learners learn and adapt to new contexts. Furthermore, this approach allows us to listen to the voice of the young learners, to take care of their point of view, creating ample space for open discussion. Unfortunately, it is customary in educational work to take it for granted that we educators know what is best for our young learners and evaluate them, because this is our job. We believe we know what they are capable of doing and what is best for them without asking. A young learner-centred model can encourage young learners to take more responsibility for their own learning and improve their motivation, strengthening personal resources during transitions and helping them develop the skills they need to cope with change.

This approach involves adapting instruction to different learning styles and needs of young learners. For example, it is possible to implement differentiated instructions and personalised learning plans to help young learners improve their autonomy and awareness of how they learn, helping to adapt to a new environment effectively. By allowing flexibility in how young learners demonstrate mastery of content, such as through project-based learning, portfolios, or assessments that reflect individual learning goals, teachers can create more inclusive environments that support all young learners during transitions (Tomlinson, 2017).

Finally, the young learner-centred approach focuses on the importance of creating a classroom environment that creates a sense of belonging and emotional safety. This is especially important during horizontal transitions, when young learners may feel uncertain or disconnected from the new environment. A welcoming and inclusive school environment helps ease the transition and helps young learners feel valued and understood as they adapt and acclimatise to their new environment.

Participation in the transition process

Student participation in decision-making and the learning process is another key component of successful transitions. When young learners are actively involved in shaping their educational experience, they develop a greater sense of ownership and agency, which can help them manage the challenges of moving between learning environments. Participation not only empowers young learners but also helps educators and administrators understand young learners’ needs and preferences, allowing for better support during transitions (Eden et al, 2024).

One effective way to promote student participation during transitions is through student-led conferences or transition meetings. In these meetings, young learners, parents, and teachers come together to discuss the young learner’s strengths, challenges, and goals, giving the young learner a voice in their educational journey (Eden et al, 2024). Bailey and Guskey (2001) point out that student-led conferences encourage young learners to actively engage in their own educational process. By discussing their progress, strengths, and areas for improvement directly with parents and teachers, young learners gain a stronger sense of responsibility and ownership over their learning journey, which can be especially beneficial during times of transition

It must be considered that one of the greatest risks of a transition, in our opinion, is that of losing one’s identity or part of it. Consider a child facing vulnerabilities who, despite great effort, works to discover and build their strengths. With each transition, this process can be disrupted, slowed down, or even undone. Similarly, think of an adult refugee, forced to leave their home, culture, and everything that is familiar. Having grown up in a certain environment that shaped their identity, they now face the challenge of adapting to a new culture, language, and people. Without a support network to guide them through this transition or a welcoming community to create a safe space in their new environment, there is a risk that they may lose important parts of their identity.

Peer collaboration and mentorship programs can enhance young learner participation during transitions. When young learners are encouraged to work together, whether through group projects or peer-led activities, they develop social skills and build relationships that help ease the stress of transitioning. Peer mentoring programs, where older or more experienced young learners guide those who are new to the school or classroom, have been shown to improve social integration and academic outcomes (Graham et al., 2022). These programs provide young learners with both academic support and a sense of community, making the transition process smoother.

The benefits of a learner-centred and participatory approach

In summary, implementing a learner-centred and participatory approach during horizontal transitions has several benefits. First, it increases engagement, which is particularly important during transitions when young learners may feel disconnected or overwhelmed. Engaged young learners are more likely to be motivated, participate actively in class, and demonstrate better academic outcomes. By focusing on student interests and involving them in their own learning, educators can help maintain engagement even during challenging transitions.

Furthermore, a learner-centred approach promotes the development of critical skills such as self-regulation, problem-solving, and adaptability, which are essential for managing transitions. When young learners are given the autonomy to make decisions about their learning and are supported in reflecting on their progress, they become more independent learners who can adjust to new academic environments with confidence (Evans & Boucher, 2015).

While autonomy and a learner-centred approach are important in transition processes, challenges arise due to inherent power imbalances in educational settings. It is important to keep in mind that young learners may not always have the authority to make decisions about their learning, as policies, school expectations, and curriculum standards often dictate certain aspects of their educational experience. Additionally, some decisions—particularly those involving transitions or support needs—are made by teachers, administrators, or parents who may feel they are acting in the young learner’s best interest. This dynamic can limit young learners’ agency, requiring educators to be mindful of these constraints and strive to create opportunities for genuine choice and involvement within the structure of their roles.

Finally, this approach creates a sense of belonging and community within the school, which is crucial for successful transitions. Young learners who feel supported and connected to their peers and teachers are more likely to adapt positively to new environments. Research indicates that schools that emphasise student participation and a learner-centredapproach see lower dropout rates and improved social-emotional outcomes for young learners during transitions(Crosnoe, 2011). A learner-centred approach that promotes active student participation is essential in managing horizontal transitions in the educational system. By tailoring education to individual student needs and involving young learners in decision-making, schools can create a supportive environment that fosters academic success and emotional well-being. Encouraging student participation through peer collaboration, mentorship, and reflection activities helps young learners develop the skills needed to adapt to new environments and remain engaged in their education. Ultimately, this approach supports young learners in navigating the challenges of horizontal transitions with greater confidence and resilience.

Developing an educational network

A network facilitating information sharing among teachers, support staff, families, and young learners involved with a transfer student is essential for a smooth horizontal transition. This network can communicate and share details about the young learner’s achievements, learning progress, and friendships.

Communication and coordination between schools are particularly important in the case of children with SEN, as different schools are likely to offer different resources and support. Effective liaison and coordination between schools and local authorities are vital, given the diverse policies on inclusive education, support, and funding across countries, local authorities, and schools.

In the London Borough of Newham, England, the SEN team facilitates a smooth transition by attending transfer reviews for young learners with EHC (Education, Health and Care) plans in the summer term prior to the young learner’s admission. They meet with pupils with SEN and coordinate appropriate provision when a child with SEN changes schools (Little Ilford School, 2022). Student profiles are devised for all young learners on the SEN Register; these profiles are issued to teachers and teaching assistants so that they are aware of the needs of these young learners (ibid). Appropriate information sharing and coordination through such networks can support seamless horizontal transitions for pupils.

In some US schools, transition coordinators have been introduced to prepare young learners with disabilities for life after school. They have valuable resources and support smooth transitions for young learners with disabilities by linking them to resources within and outside the community and school (Scheef and Mahfouz, 2020). In this way, the coordinators support smooth transitions between schools and from school to community.

Training programs for teachers, support staff and young learners

To develop a support system for transfer students, a training program is needed for all teachers, support staff, and volunteers. This program creates an understanding of the psychological challenges associated with transitioning to a new environment and the various barriers that such a transition presents. In these training programs, teachers and support staff should participate in role-playing and reflection exercises that focus on two key areas: (i) the challenges a young learner might face when changing schools, and, (ii) how they would want to be treated by teachers, peers, and support staff if they were in a similar situation.

In addition to understanding these difficulties, teachers and staff should explore the human and material resources available within the school and community that can support transfer young learners in precarious situations. They should contemplate specific support strategies such as individualised learning support, utilising local networks, offering pre-school during long holidays, and other concrete measures. Through such training, teachers and support staff can gain insights into facilitating a smooth ‘horizontal transition’ for each young learner, effectively utilising available resources in the school and community.

The Spanish government’s National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training also places a particular emphasis on inclusive education, student diversity and intercultural education with the provision of professional learning programs for teachers (Brown et al, 2022). These programs focus on raising teachers’ awareness of young learners’ academic as well as social and emotional needs (ibid).

Such a training program could also be useful for children to prevent bullying of transfer students. In some cases, organising training or workshops for children to reflect on the difficulties faced by transitioning pupils can be beneficial. Through such opportunities, children can gain empathy for learners with different needs, foster positive friendships, and value their unique backgrounds and roots.

Conclusion

In conclusion, horizontal transitions in education are complex and require a coordinated approach to ensure young learners’ academic, social, and emotional well-being. The case from southern Italy at the beginning of the chapter demonstrates the importance of building a collaborative network involving teachers, families, health professionals, and community organisations. This network successfully tailored a support system that improved the young learner’s behaviour, reduced family stress, and maintained social connections. Schlossberg’s transition theory highlights that resources such as coping strategies, support networks, and personal attributes play a key role in determining whether a transition is positive or negative. Vulnerable young learners, including those with disabilities or displaced due to migration, are especially in need of personalised interventions to prevent disruption to their development and identity. Peer and teacher relationships are crucial, as they provide stability and a sense of belonging. Involving families and communities further strengthens the support system, ensuring a holistic approach to transitions. Open communication between stakeholders is essential to managing expectations and addressing challenges proactively, while professional development equips educators to better understand and support young learners through these changes. Ultimately, successful horizontal transitions are driven by a student-centred approach that recognizes individual needs and creates flexibility, emotional support, and inclusive environments. By engaging all stakeholders, schools can help young learners navigate transitions with confidence, resilience, and continuity in their personal and academic growth.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- In what ways can peer support and teacher relationships reduce the stress of horizontal transitions, and what strategies can schools implement to cultivate these supportive relationships?

- What factors should be considered when designing personalised educational plans during horizontal transitions, especially for young learners with complex needs or behavioural challenges?

- How can educators and support staff ensure that vulnerable young learners—such as those with behavioural difficulties or special needs—receive personalised interventions during horizontal transitions without disrupting their development or sense of identity?

- In the context of horizontal transitions, how can communication and collaboration between schools, families, and external organisations be improved to provide a seamless and supportive experience for young learners, particularly those moving between different educational programs or systems?