Section 4: Fostering Student Well-Being and Emotional Health

Identity Politics – Labeling in Education

Sam Blanckensee; Özge Özdemir; Lina Render de Barros; and Josefine Wagner

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

The examples we chose are multilayered and a complex part of our everyday experiences at school. You might have already witnessed similar or very different, but equally complex incidents. You might have engaged spontaneously, tried to overlook it, felt helpless, angry or shocked or even confident. With the example cases, we suggest taking a closer look at different angles of these complex situations. This might help you to navigate complexity and dilemmas in the future. Feel free to add your own experiences, questions, worries and good practice. It might be helpful to read the examples and discuss the questions that follow each situation with a partner.

Example Case 1 – Negotiating friendships and (group) identities between religious dogma, racist stigma, liberal values and LGBTIQ* rights

“So I remembered an example from school where a group of otherwise very well-adapted girls, friends even, excellent students, were suddenly found split in two different groups, shouting at each other in the courtyard. They looked like they had ganged up against each other, like a mob. People in one group were shouting: “If you don’t respect LGBTQ rights, we don’t respect your religion”. And the other group started to shout: “You’re a bunch of racists” and then some boys entered the group and started shouting “Allahu Akbar”.

- What is going on here?

- How are you going to deal with this as a teacher? How can you make sense of this situation?

- How can you interfere without reproducing racism or discrimination against LGBTIQ* or Muslim students?

- How could this have been prevented? How could this be mediated?

- How can we develop solidarity between marginalised groups? What kind of feelings could this situation provoke in queer muslim kids or colleagues?

- Who is being homogenised? By whom or what?

- How were your immediate emotional responses? Did you take a side? Which one was it? Why? Try to imagine yourself taking the other side. What is different?”

Example Case 2 – The Girl that was a Horse

“In one of my internships at primary school, the class teacher referred to one of the girls, let’s call her Elen, as a horse. Not because she really believed Elen to be a horse, but because Elen would refer to herself as a horse. Elen had been diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and had had difficult school experiences with other teachers. Apart from the FAS label, she had been labelled as being unable to sit still or concentrate. This teacher was an experienced primary school teacher in her late 50s. Her radical acceptance of Elen’s self-identification manifested in her use of Elen’s language and adopting and expanding it. Elen did quite well at school and got along well with classmates and the teacher. When she had difficulties concentrating or started acting out by neighing or pawing the ‘hooves’ in class, the teacher would remind her that the classroom was not very well suited for wild horses. She would ask her whether she was a domestic horse, a racehorse or a wild horse at that moment, and would suggest the courtyard as an appropriate environment for wild horses. The girl then sometimes chose the courtyard and ran around neighing until she came back to play and interact with the people in class, or she would choose the domestic or race horse and start with exercises or games in the classroom.

- What is going on here?

- How are you going to deal with this as a teacher? How can you make sense of this situation?

- Have you ever been in a situation where somebody’s reality is radically different to your own?

- What role does power (teacher-student, adult-child, rich-poor …) play in affirming, accepting, playing with or attacking people’s versions of reality, especially with regard to the sense of self?

- In what respect is the teacher in a position of power in this situation?

- How does the behaviour of the teacher likely affect the behaviour of Elen, the behaviour of the class and of other parents?

- Imagine a different approach of the teacher, where she negates Elen’s version of reality. What effect would this have on Elen, the class, or other parents?

- In Q5, you have reflected on the position of power of the teacher, in how far is Elen in a position of power, or the class and the parents?”

Initial questions

- How do you describe yourself? Are there any ways that you describe yourself that are especially important to you?

- Have you ever been labelled in a way that made you feel uncomfortable? How was that? Did it have any impact on how that person treated you?

- How do labelling and identity politics influence students’ learning experiences and full participation in education?

- What are the challenges teachers face with regard to identity politics and labelling?

- How can we recognise that students are affected by structural discrimination and how can we empower students with multiple identities?

Introduction to Topic

We, the authors, of this text write with sometimes divergent understandings of difference as we come from different schools of thought and also different biographical experiences, privileges and experiences of discrimination. All Means All is a collaboration of teachers, students, activists and academics from different fields. We speak to you as educators, and as people, whose perspectives on the world have been shaped by theory and academia as well as by activism motivated by the experiences of exclusions that sexist, trans-misogynistic, heteronormative, capitalist, racist societies create. We would like to sensitise teachers and trainees for the struggles students face as they try to develop a sense of who they are.

However, we also want to engage you with our own voices as teachers who are personally affected by discourses that deny us, our friends or our families the right to expression and existence. As we advocate for full personhood of students and educators – inside and outside of the classroom – we also want to highlight, and reflect, on the difficult decisions teachers need to make during everyday classroom dilemmas. It is not easy to generate effective solutions to bullying or to find the correct words when children’s views or actions limit the abilities of others. It is also no small feat to understand, work with or confront the structural conditions of schooling. Mass institutions, such as public education systems, designate certain roles and tasks to children and adults in ways that appear to be driven by the logics of bureaucracy and austerity politics, instead of the wellbeing of those involved. Nonetheless, schools are important spaces with regard to personal and social learning, in which we can set examples for living peacefully with each other and for learning how to navigate conflict, negotiate, argue, or reconcile, and how to stand up for ourselves and others and be part of a community.

Throughout this chapter we invite you to reflect on your own experiences, biographies, overwhelming feelings, powerlessness, agency and privilege. In our group of four, we combine people with backgrounds in disability studies, teaching, teacher training, political education and anti-discrimination work. We have German, Irish, Kurdish and Brazilian roots, and we hold passports from three continents. We identify with the journeys and struggles of neurodivergent, trans* and queer people. We have been labelled and have applied labels to ourselves and to others. All these experiences help us to better understand the sometimes conflicting demands that are put on recognising differences, normalising differences, but also emancipating ourselves from prescribed norms and oppressive structures.

Our chapter starts with scenarios from everyday school experiences, which illustrate some of the core questions and challenges that teachers deal with on a daily basis. A key challenge is the difficulty between naming yourself and being named by others. The case studies help to understand the practical consequences of this dilemma around identities. On the one hand, while labels are used to allocate resources, they can also be used to categorise marginalised and disenfranchised people, without their consent and consequently result in further stigma. At the same time these labels can be adapted, (re-)appropriated or (re-)invented by groups of people to make claims for participation and share of resources.

As a potential tool to navigating this dilemma on how best to support young people in their way of being, in encouraging playfulness around identity with or without labels, while at the same time understanding and drawing boundaries to protect those affected by discrimination, we introduce May-Anh Boger’s concept of the trilemma of inclusion. Her empirical study and model offers a theoretical framework which contextualises the dilemmas, or rather trilemmas, that we encounter and exemplify in our interviews with Danielle, Özge and Sam.

Having a look at our example cases

The example cases in the introduction illustrate the value, and necessity, of respecting and understanding our students’ expressions of who they are. In the second example, adopting Elen’s language and developing it into pedagogical metaphors helped her to become aware of her behaviour and needs, without feeling rejected. She learned to differentiate her needs and develop an awareness of when she wanted to sit and concentrate on a task, or when she needed to self-regulate impulses through exercise. Instead of merely seeing Elen through the lens of deficit or her special needs label, the educator worked with the student’s imagination. She followed her lead and was able to pick up on the individual student’s creativity, resources and needs. The student’s imagination then started to become a resource for communication of needs and a tool for self-regulation. This illustrates how our perception of students can be transformative?

On a superficial level the first example at the beginning of the chapter seems to be a miniature reproduction of conflicts between religious dogma, on the one hand, and LGBTIQ* rights on the other. If we see only mutually exclusive templates or prototypes of religiousness and LGBTIQ*, it is very hard to mitigate this very real conflict in the present. Conflicts at school that seem to appeal to a supposed opposition of religion and homosexuality, transgender[1] and queer identities are often rooted in a secure world view. As students mature, they begin to explore their place in society, and begin to develop their political standpoints and opinions. This is particularly challenging, especially if one feels that these positions are mutually exclusive. Students play with, provoke, and change their positions and attitudes, if they are given the opportunities. Individual positions often reflect belonging or isolation from a social group. So if a student comes from a conservative Muslim family that teaches their children to respect others independently of their gender or sexual orientation, this student may still feel the need to experiment with expressions of queerphobia, since the social discourses in Europe construct Islam as being in opposition to LGBTIQ* rights. Students who try to find their Muslim identity in the midst of predominantly Christian societies, and where anti-Muslim racism is increasingly viewed as a concern, might be experimenting, rather than conveying, a fixed mindset or being aware of the fact that they are (re-)producing hate. It is important for teachers to know exactly where freedom of expression ends and discrimination begins. It is equally important to be able to see that students are still developing and experimenting with ideas, opinions and boundaries and finding ways to view students not according to tabloid headlines, but rather in their complexity as a whole. As teachers, we need to face social and political realities inside and outside of the classroom.

If these example cases seem straightforward to you, you may want to focus on the questions in the following paragraphs. If you also wonder, or worry, about how to act or react in complex everyday interactions with students, the following paragraphs may help. We have collected suggestions and questions for self reflection which requires you to think, and respond, to. Every student becoming a teacher needs to find his, or her, own personality in the classroom within a professional, pedagogical and ethical framework. You can use the theory-loaded ideas as guidelines with regards to the creation of your pedagogical framework and the questions can help you to reflect on what kind of teacher you would like to be, and on how best to develop, sharpen, and (re-)invent your professional identity.

Teachers today are expected to create a surrounding where every student can reach their potential and thrive. They are expected to negotiate boundaries and support the development and practice of ethics and behavioural expectations. Teachers are currently struggling to understand and negotiate the complexity of identities, the language around identity discourses, student’s needs and the structural discrimination and violence of various types students may face in schools.

How can teachers navigate these complexities of classroom realities: identity construction, individuality, belonging, discrimination, violence? You are already working on the first step: becoming aware of the complexity. We need to respect that complexity, to avoid reproducing exclusionary discourses or erasures. Becoming aware of power and social hierarchies is another important step in preventing (structural) violence. I, as a teacher, can only intervene if I recognise violence, so I need to educate myself about it. Apart from academic education and activist literature, an important source of information are the students themselves. We need to learn to listen. One possibility to protect students from structural discrimination and violence in the classroom is to create spaces and relationships in which they feel seen and valued as a person with multiple aspects of their identity. In these spaces students are visible to the teachers as more than simply their role as students. Students get the chance to determine themselves, with which part of their identities they want to become visible to the class and/or the teacher. The feeling of security stemming from these kinds of relationships is one central aspect for the prevention of violence. Furthermore, it also offers possibilities for interventions. Only if we are aware, witnessing or being told about boundaries can we successfully intervene. In the following paragraphs we will further develop this first step of becoming aware of the complexity of identity and identity construction in postmodern societies, we will then take a closer look at labelling and its critique as well as identity politics and its critique. We will see that a conflict arises between a strong critique of labelling and an identity politics approach. We will sketch Boger’s model (2023), the trillmatic theory of inclusion, to navigate this conflict and show how the model can be a tool to increase your own tolerance of ambiguity and also your agency in the classroom.

Naming Yourself and Naming Others: Why does it matter?

What is the difference, you might wonder, between claiming an identity and being labelled? To make it short, the latter is creating knowledge about “others”, ‘objects of knowledge’ so to speak, while the first is actively taking a subject position. It is crucial to understand the context within which “claiming an identity” emerged as a liberatory and emancipatory act, rooted in social movements that advocated for solidarity and gaining political power for marginalised groups in a pluralistic society. “Labelling” on the other hand is a passive experience as it implies the individual is being given a marker that it may or may not identify with. Labels organise and structure reality, they influence expectations and in the field of education, disability studies and social services are often a prerequisite to access to the social and health systems.

A central argument in this article is that an understanding of theory, theoretical models and politics on identity, society, discrimination, power, labelling will help you navigate the complex everyday interactions taking place in schools. We want to encourage everybody to understand the theory, as this can affect your ability to analyse everyday situations in their complexity and provide you with opportunities to (re-)gain agency in otherwise often overwhelming situations.

What is identity?

The question of identity can roughly be translated to the question “Who am I?”. While the answer to that question may change over time, places and contexts, it also suggests a kind of stability and continuity, since the answer can only be understood if it refers to the object the question has been about. The following argument is based on a non-essentialist sociological and social-psychological concept of identity as presented by Heiner Keupp, Jean-Claude Kaufmann and Zygmunt Bauman. Identity is understood as the concept with which an individual makes sense of one’s experiences. It is a central point of reference for the interpretation of all experiences internal and external and initiating everyday task solving (Keupp et al., 2008: 60). Identity construction is not only an individual’s choice. It is the process of constructing a subject that has the ability to act, despite contradictory environments and the resulting contradictory demands. The production of coherence and the ability to bear ambiguities are no oppositional goals, instead they complement each other in making identity possible and balancing out different areas/aspects of life (Render, 2014).

There are social and historical reasons behind the emergence of the concept of “identity” and the omnipresence of the question “Who am I?”. Society has changed rapidly and many shared belief systems and stories (known as meta-narratives) are being deconstructed or drastically altered. Processes such as globalisation, migration movements, emerging democracies, and the internet have contributed to this change, along with the availability of information online and the acceleration of social interaction through technology. These processes lead to changes in the way societies organise themselves and established concepts such as families, nation states, religion and gender are now increasingly being challenged and questioned. As these concepts are being broken down, people are less and less bound to external determination (e.g. farmer, clergy, nobility or husband, wife, child, grandparent). This situation is simultaneously liberating (offering possibilities to be different – not determined by birth), violent (uprooting from communities and concepts that had offered orientation and a sense of belonging) and creating a need / obligation of identity construction. If your faith and future are not determined by birth – if it is not clear to everyone who you are, or have the potential to become, people will ask themselves and others who they are and want to be(come) in order to make sense of the social world. This historical period is called Late Modernity or Liquid Modernity (Bauman, 2010).

This loosening of social ties brings freedom of choice on the one hand, and uncertainties on the other. The institutions that structure and give meaning to life are increasingly being questioned. Institutions and ways of organisation that offer alternatives to institutions such as religions, hetero-normative family models, gender binary, and the power of nation-states. So while this might feel like freedom to some, it might feel like a loss or an uprooting from community to others. People now not only can choose what they believe in, they also have to choose in order to construct their identity. You can choose who you are and want to be, but you also have to choose. Create your identity. Social Media, Tiktok, Instagram and others can be regarded as a means of creating and sharing an image of oneself, but also as creating and (re-)inventing oneself.

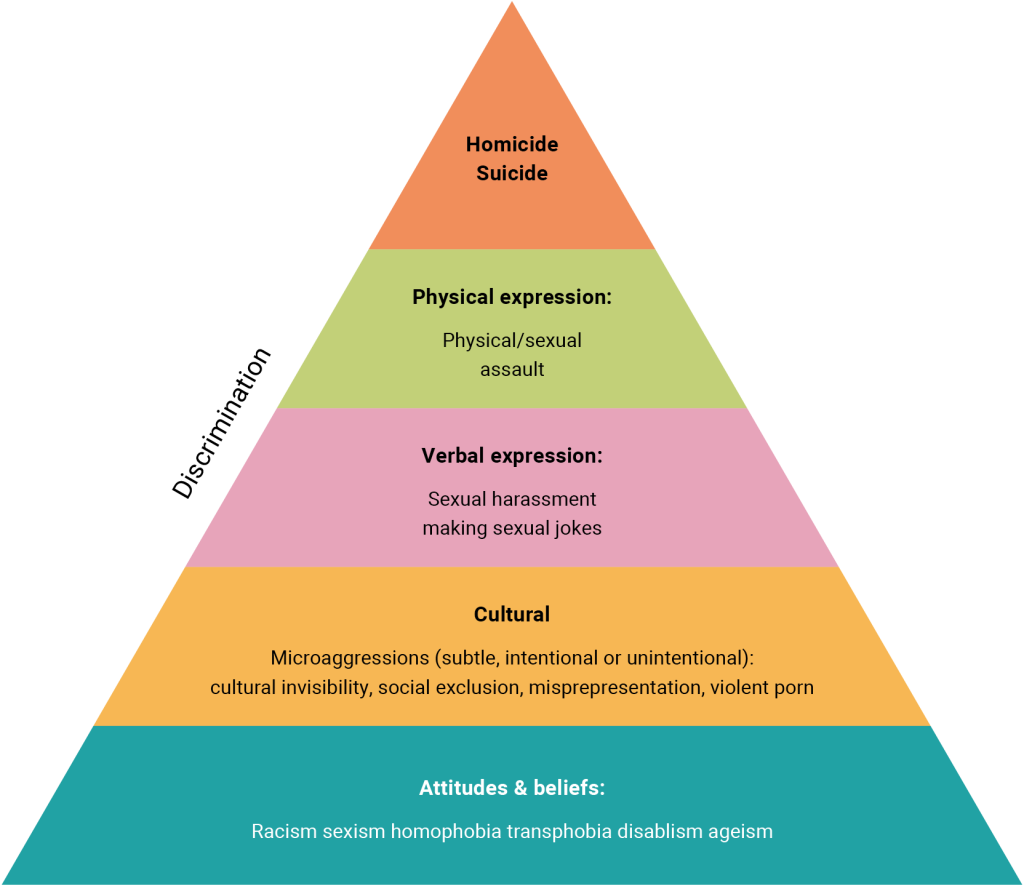

In a society where “identity” holds such a prominent place, it is valid to conceptualise “identity markers” which can be considered as a new form of capital interchangeable with economic, cultural and social capital (Bourdieu, 1997). Since identity construction is not only an individual choice, but also depends on recognition by others through validation and confirmation, the need for the construction of identities introduces a new dimension of suffering for marginalised individuals (Render, 2014). There may be less resources available for some individuals to construct their identities, and the flexibility of constructing one’s identity can offer more or less opportunities. In regard to the identity- process, the unequal distribution of resources is not only important on a material-existential scale, but is also of existential importance on the psychological constitution level. If I am a member of a marginalised community, there may be people who wish harm upon my group. Ignoring or avoiding the naming of the part of my identity that others want erased is a collaboration in this erasure. The erasure of people through language is a form of violence that mirrors the erasure of people through killings.

Figure 1: The Anti-Violence Continuum/Pyramid Model

Example

Anonymous – Germany

Everyone feels the need to belong or to feel connected to other people. In the context of teaching, it is important to understand the student’s emotional and social need of belonging and how it shapes their identities. In the case of poverty and stigmatisation, individuals can be denied access to recognition and identity and belonging at the same time. This implies that identity has structural determinants. Through a process of over-generalisation and elevation of identity to the state of a collective ‘identity’, identities can become powerful instruments of exclusion. At the same time, these overgeneralised aspects of identities can also be used in political struggles for example, to raise awareness of these structural determinants that benefit one group and deprivilege, or discriminate, the other.

Labelling: Being named by others

In most education systems, children with special needs are categorised according to a special educational needs status in order to allocate resources in support of these students. In Germany, for example, there are up to eight different categories that students can qualify for: sight, learning, emotional and social development, speech, mental development, hearing, physical and motor development and instruction for sick pupils (KMK, 2023). In other education systems, differentiation varies. Usually, special educators, doctors or psychologists, diagnose students with specific needs through standardised testing. Students are either already registered at schools with special needs labels, or are later indicated for testing by teachers, parents or educators. When difficulties in the classroom arise and they are unable to keep up with tasks, they are frequently mentally or physically absent, or show sexualised or overly provocative or violent behaviour. Their “disability” becomes translated into a pedagogical special needs diagnosis that offers different types of support measures. For example, a student who is diagnosed with a learning disability has the right to special assistance by a special needs teacher. A student who is diagnosed with intellectual delay, receives the right to more hours with a special needs teacher. What is common to all special needs diagnosis is that they are formulated under a deficit hypothesis. This means that a student is assessed through the lens of what they are not able to do, and compared to an (imaginative) average child. This view might be “thickened” through repeated iterations which in-turn produces a limiting belief set and likely impacts students’ sense of self (Wortham, 2006; Pfahl, 2011; Wagner, 2023).

The history of separating students according to different educational needs, and creating a divide between regular students and those deemed ineligible to participate in mainstream education, became institutionalised through the first special schools. These were established to cater for the needs of children with sensory impairments, i.e. schools for the blind or the deaf. Such developments took place in Western Europe during the late 18th century. With the turn of the 20th century, so-called “help schools” were established in Germany and were mostly attended by children from lower socio-economic backgrounds to address the needs of children who lack care and support. Help schools also alleviated the stresses of mainstream schools. Therefore, they had two main functions: provide education to those who need more support and alleviate the need for regular schools to create provisions for children seen as morally and intellectually “inferior”. Later, these schools continued to support children with learning disabilities, social and emotional development or cognitive delay. During the Nazi era, children that attended special schools were targeted for sterilisation and those who did not succeed in special schools were considered ‘ineducable’ which served as a criterion for murder under the term ‘euthanasia’ (Hänsel, 2006). After World War II, special schools continued to operate. A special educational needs label has now become a bureaucratic mechanism for which students are referred to different types of schools. While it is important to mention that children with intellectual impairments did not receive any education for many decades, the establishment of special schools also led to stigmatisation by communities (parents, other children, teachers, etc.) and by the students attending special schools (Schumann, 2007). With the emergence of inclusive education in the 1970s, a number of students who were labeled with severe additional needs (often labeled as special school students) could continue their education in primary schools and received additional support by former special school teachers in a regular classroom. The label also served as a prerequisite for the allocation of additional resources.

In contemporary inclusive schools, children often become affiliated with certain labels to administer extra support. Children with learning difficulties or disabilities might have a special needs status, whereas children whose families migrated to a new country may need more support and are seen as children with a migration background or second language learners. These additional markers are not typically diagnosed, but rather attributed through (first) subjective impressions and often do not lead to the allocation of further resources. In other words, they are not necessarily connected to a deficit, but they often imply a deficitary lens and thus create differences. A favourable reading of markers allows us to say that they are intended to offer additional support for children through state funding. A label could allow a child to receive more time during a test or assistance from specialised members of staff or extra language classes. These measures are intended to support students within an inclusive setting. However, research on stigma and subjectification (Goffmann, 1963/2010; Pfahl, 2011; Pfahl & Powell, 2014) has shown that labels can have an impact on students’ self-concept and thereby ability to perform. In the German context, this mechanism has been described as the “Etikettierungs-Ressourcen-Dilemma” (Füssel & Kretschmann, 1993), highlighting the predicament how resources are linked to labelling, while a label usually carries a set of expectations and behaviours that a child must exhibit to access the necessary resources.

It can be said that labels are an approach used by an education system to guarantee individual legal entitlements, and these legal entitlements have changed over time in terms of the location and form of special support (United Nations, 2006). However, the stigmatising element is problematic, both in terms of outside attribution and from the learners themselves. As students with labels like special educational needs often have access to resources (e.g. special education teachers, assistants), it can sometimes lead to a differentiation of “my students”/”your students”. This is different to other dimensions of diversity, as resources are rarely allocated based on such differences.

The concept students have of themselves plays an important role in the way they view themselves as capable members of the classroom community (Rubin, 2007). This is particularly the case at the intersection of racialised minority status, socio-economic conditions and learning difficulties, where some school systems are poorly equipped to offer teaching content that is accessible for students with a variety of different needs – whether due to mental health or abilities, stigma, different first languages, bullying, discrimination or violence. In Germany and Austria, for example, children who speak Turkish or Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian at home are more likely to attend special schools than mainstream institutions (Statistik Austria, 2022/23: 25). Waitoller and Ammanna (2017) have emphasised the importance of space and location in how student identities are viewed negatively in relation to expectations around performance and success. Individual districts as well as urban versus rural neighbourhoods offer very different interpretations of student backgrounds. In rural settings, comprehensive schools are often the only choice for all children in the community, whereas in urban centres competition around specific schools creates hierarchies between academic bourgeois secondary schools and comprehensive schools. The latter is often dominated by students who are designated as more disadvantaged, such as migrant children or those whose abilities are considered below average. While such schools may exist in rural settings, they become a place to divide student populations according to specific identity formations (Nasir & Saxe, 2003).

Therefore, we are concerned with questions around naming differences and creating specific realities around labels and identities. When does it serve a child to be labelled in a particular way? How invisible can a label really be? When does visibility cause suffering and when does invisibility create pain? How can we grant special provisions to students who need support without labelling them publicly? And when do these practices preclude the possibilities of participation of children and limit their engagement with teaching content and classroom peers? While schools often encourage children to introduce aspects of their culture in the mainstream classroom, these events can become token incidents that blur the much more subtle preconceptions around students’ cultural backgrounds. When do children feel seen and appreciated? And when do students’ multiple perspectives – due to their presumable differences – strengthen the understanding of the group regarding complex issues?

Identity politics: Naming yourself

Claiming Identity as an emancipatory practice

The term “identity politics” was introduced by the Combahee River Collective, a black feminist lesbian socialist collective: “as children we realised that we were different from boys and that we were treated differently – for example, when we were told in the same breath to be quiet both for the sake of being ‘ladylike’ and to make us less objectionable in the eyes of white people. In the process of consciousness-raising, actually life-sharing, we began to recognise the commonality of our experiences and, from the sharing and growing consciousness, to build a politics that will change our lives and inevitably end our oppression” (Combahee River Collective, 1977).

The central idea of identity politics lies in turning around a shared experience of marginalisation, humiliation or discrimination by adopting a label, derogatory term or external definition (crip, queer, f-gg-t, black, N*Word, …) for oneself (Alick, 2023; Worthen, 2023). This process is called reappropriation and holds the possibility of using the language of power that has separated and degraded human beings. This language of power, with its derogatory terms, turns people into projections that serve self-identification. It turns them into objects of a range of emotions such as hate, fear, fantasy or pity. The seemingly counterintuitive act of appropriating a term that is often used to humiliate or belittle, can be extremely powerful, if done collectively. Through the collective process of identification and redefinition of the labels or categories, individuals are no longer mere objects of this process. They become powerful subjects, claiming spaces in public discourse, politics and (re-)gaining access to rights and resources formerly withheld. The function and purpose of identity politics is consequently to point out how universal promises implied in the declaration of human rights, often fall short and are being used to protect the rights and interests of particular social groups (Dowling et al., 2017). When the advantages of some groups become normalised and accepted and almost invisible to those growing up with them, we call these advantages privilege. The status quo is already a type of identity politics, we just tend to label it as “normal”. Have you ever thought of Christian Democratic Parties in predominantly Christian European countries as actors in the field of identity politics? Some prominent examples of emancipatory movements that are also publicly viewed as identity politics on the other hand are: The black Lives Matter movement, Kanak Attack (Germany), the Zapatista resistance (Mexiko), the MST Landless Worker Movement (Brasil) or the #Metoo movement, just to name a few.

Identity politics is controversially discussed, often by those who are unaware of their own privileges, but not necessarily in positions of power. This is not surprising since identity politics is a tool to call for a redistribution of resources, such as money, access to health care and education, and access to social and political participation. If people are not in positions of power and economically disenfranchised, and unaware of e.g. white privilege, they might feel threatened by calls to redistribute resources that do not centre or even further decenter their own experiences. Instead, they may understand a shared oppression and include the fight for BIPoC rights, people with disabilities, queers in their own struggles for dignity and liberation.

The Dilemma

With all of the above in mind, it can be said that labels can be problematic as they can limit our capacities of self-expression, they can also be mistaken and tend to be somewhat reductionist since they can never encapsulate a person’s complexity and reality of their experiences. However, labels are also a pragmatic way to claim special support that enables individuals to access resources and spaces. Some of the information that labels carry might also hold useful insights to the individual or might be taken on voluntarily as an emancipatory act. Therefore, labelling can be perceived as a balancing act, weighing the pros and cons of being named, on the one hand, while claiming an identity on the other. In the next part we will discuss a model that helps understanding the challenges and also this act of balancing.

Working with the Trilemma

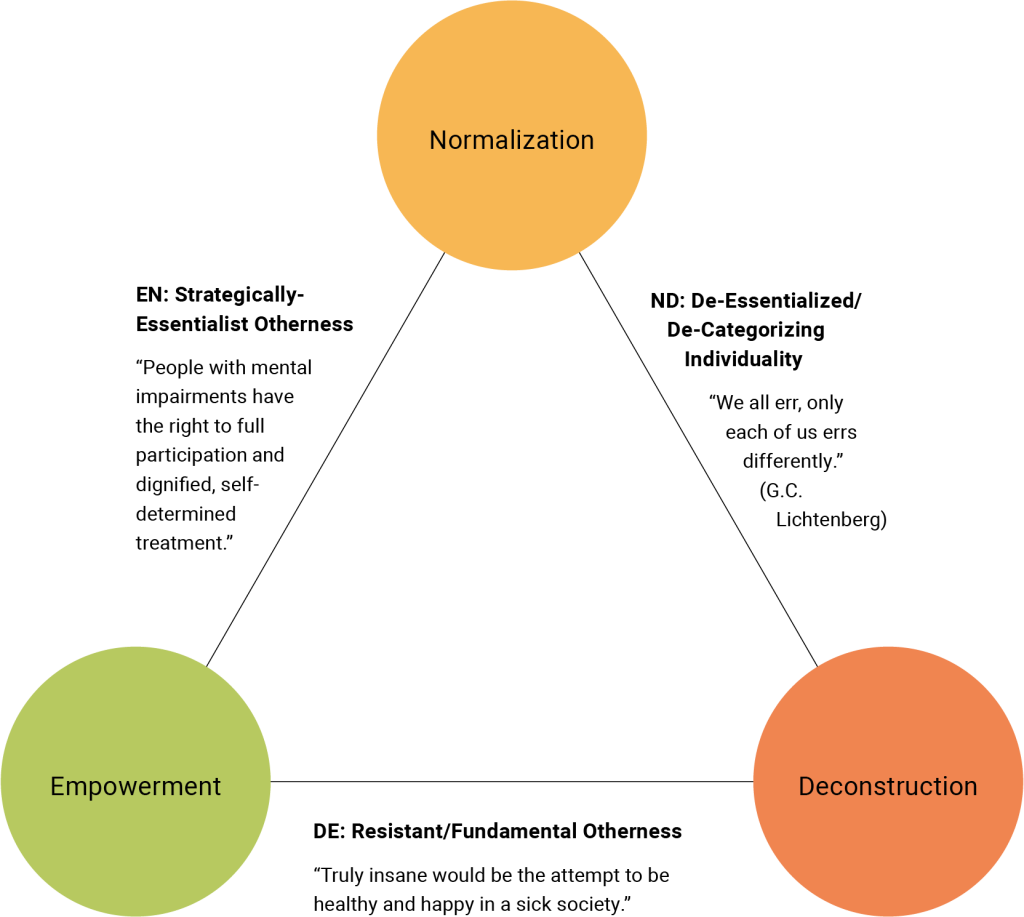

The trilemma of inclusion is a theoretical model by May-Anh Boger (2023) that helps us navigate the dilemma between identity politics and a radical critique of labelling. It offers insights into the dynamics of how groups deal with oppression. Through empirical research, she highlights how the struggle against oppression manifests in various ways. She challenges the notion that what is expected from oppressed people is very often contradictory, and therefore the solutions to oppression are also often contradictory.

Three Dimensions

May-Anh Boger outlines the three dimensions of the trilemma; empowerment, normalisation and deconstruction. Her findings show that it’s impossible to follow the three different strategies at the same time. You can follow one. But if you follow two, the third is automatically excluded. So when labelling in education is critically discussed, this often occurs within a deconstructionist approach (‘labels are bad, because they limit our capacity of self-expression and they are wrong, because they never cover the complexity of reality’), while for identity politics this is often undertaken through empowerment and normalisation (‘I am x and as x I should get access to y’).

When we discussed the role of labelling and the role of identity politics in inclusive education, there was some controversy in the beginning. The perspectives of the four authors of this text included self-advocacy with regard to working class identity, neurodiversity, trans rights, queer rights, lesbian and gay rights, racisms and also cis, straight, white perspectives, formal teacher training special education and secondary schools, political educator in NGOs, sociology, HR, activism, feminism, care work and mental health.

From the biographical perspective of a special education teacher and researcher in the field of special education teacher training, there was a strong need to deconstruct labels and show the harm they do in the school system with regard to migration background, class and disability. As a reaction to the strong activist position for a call for deconstruction, one of the authors felt threatened and maintained the empowerment and normalisation position. This could be summarised as follows. The special education teacher says: “Since labels are bad, because they limit students’ development and they are for the most part oversimplifications and never fully accurate, we should abolish labels altogether.” The queer activist says, on the other hand: “I’m a Lesbian and am not giving up the labels, ‘Lesbian’ nor ‘Queer’”.

The first step of working together was understanding the difference between naming yourself and being named by others. The trilemma then helps us to understand what is happening among us on a deeper level. While all three aspects empowerment, deconstruction and normalisation are important, not all of them can be adopted at the same time. It gave us a way out saying that all the points are valid.

Practical Consequences of the Trilemmatic Theory of Inclusion

This experience can be very helpful for teachers to understand that, if you make any emancipatory statement with regard to a marginalised group, it can at most follow two of three emancipatory strategies: empowerment, normalisation or deconstruction. Since it automatically excludes one of the other strategies, for example, a student or a colleague might take the excluded position as they feel that their strategy has been threatened by the position you have taken. A practical consequence of the trilemma is an understanding of this dynamic and taking a step back and realising its impact, and attempting to include different strategies in similar statements and to encourage conversations on this topic with older students or colleagues.

Figure 2: Examples of self-understanding as (not)in_sane applied to the trilemma

Example Cases of three individuals navigating the trilemma

As discussed in the paragraphs about identity, the process of answering the question, ‘Who am I?’ is both individual and collective. While every person’s journey is different, there are some common experiences marginalised groups share. When we refer to marginalised groups, we see this as encompassing LGBTIQ* people, disabled people, racialised people including Roma and Traveller groups, Jews, working class people, single parents, migrants, poor and homeless people and all of those living on the margins. However, there are also significant differences among people who are targets of the same ideology of inequality. Ignoring these differences within groups can contribute to tensions and render invisible specific pain and inequality (Crenshaw, 1991).

Intersectionality, as coined by Crenshaw, is a key concept that helps understand how identities work for individual learners. The intersection between two or more identities creates a different experience of marginalisation. Crenshaw (1991) argued that black women are discriminated in ways that are a combination of both racism and sexism (though not neatly fitting into the legal definitions of either), as the behaviour in the case of sexism is compared to the experiences of all women including white women, and in the case of racism to all black people including black men. This leaves the experiences of black women largely unseen, as their blackness cannot be removed from their womaness (Crenshaw, 1991).

In the context of the classroom, intersectionality speaks to how teachers and students with intersectional identities, for example, a black disabled person, would not just experience disadvantage due to racism and ableism, but also another form of disadvantage experienced when ableism and racism combine. Therefore, in this instance, an approach may be taken to recognise the complexity of identity, combining the learnings of studies in the inclusion of disabled people and anti-racism and considering the additional barriers created at the intersection. Although individuals have different experiences (due to a combination of their own identities and the relationship between those identities), there are commonalities between people who share an identity and it is useful to be aware of this.

In the video that accompanies this written chapter, you will find two of the authors (Özge and Sam) speaking with Dr. Danielle Farrel on their experiences of identities, labelling and the role of schools and teachers in facilitating students to express themselves, participate and thrive as people with complex and some marginalised identities. For the purpose of the discussion they describe themselves briefly as follows: Sam describes themself as a non-binary trans neurodivergent person, as an activist, a partner and a family member; Özge describes herself as a woman of colour, student and activist. Below we will take a few examples from the discussion to illustrate the trilemma and how it may be used within the classroom to identify solutions and strategies.

Normalisation

Normalisation, as part of the trilemma, can also be described as integration or transnormalism (Boger, 2023). Boger explains:

Normalisation (N) is defined as the process of opening privileged positions and institutions to enable full participation. Others, having multiple identities can create a stronger sense of community when engaging with others with a similar identity, similar experiences and similar emotions even if not all of those identities always overlap (2023: 21).

Normalisation can play out in a desire to raise the ‘other’ voice within normalised structures or to create a society where everyone is equally normal or equally different. As Sam explains:

“I was in a Catholic Girls school and stayed in the Catholic all-girls school until I finished, and my teachers did not know how to cope at all [with Sam being trans]… The focus was that I have to keep wearing the school uniform. Not on how I was getting on and whether everything was okay at home. My parents and I weren’t really getting on very well, and I was trying to finish my schooling but it wasn’t about supporting me. It was about making sure I follow the school rules.”

Sam (Ireland)

In this example the school was prioritising normalisation, potentially as a means of protecting the student. However, they did not support the position of normalisation with either empowerment or deconstruction, either of which may have enabled greater inclusion for the student.

Consider some strategies the school could have used using the lens of normalisation:

- They could have enabled Sam to be empowered and have a conversation about trans people in the school. If Sam identified as male, this might have meant the introduction of a boy’s uniform option and the identification of boys’ toilets. As a non-binary person it would be including non-binary options within the school setting and creating a space for non-binary people within the categories of the school.

- They could have brought in more uniform options for all students, with a focus less on gender, and the deconstruction of norms.

- Can you think of any others?

- What about strategies that empower and deconstruct rather than normalise? Could that be to take away all uniforms and gender categories and enable students to express themselves away from labels?

Deconstruction

Deconstruction within the trillemmatic framework for inclusion can also be described as dissolution or resistance (Boger, 2023).

Deconstruction (D) is defined as the process aiming at the dissolution of dichotomous orders of difference (as, for example ‘men vs. women’, ‘disabled vs. able-bodied’, ‘white vs. black/of colour’) in which the normalised is represented as desirable and as the centred position from which the others are constructed as the others and thereby

decentred.’ (2023: 21).

Deconstruction is a rejection of categorisation and the pursuit of fundamental change in how society orders itself. Danielle spoke of her experience being labelled by doctors, before she had had the opportunity to progress through life:

“And so I think it is difficult when you have or you’re faced with labels of medical diagnosis before you even meet milestones like going to school and progressing through school.”

Danielle (Scotland)

Those labels assumed a deficit in her abilities and her potential. It determined whether she could go on a school tour, go on sleepovers and how much she was expected to achieve in the eyes of her teachers. A deconstructionist look at disability would require an examination into the assumed truth, to show the power relationships and how social inequalities are presented in the lives of children. On a basic level it would mean removing labels from the classroom, and removing practices where children are categorised.

- Consider some strategies the school could have used using the lens of deconstruction:

- Paired with normalisation, they could have treated Danielle as an individual with individual needs in the classroom, while treating her classmates in the same manner. Instead of categorising students by ability or needs, they would each be treated as individuals and given individualised support, outside of any categorisation.

- Paired with empowerment, this could have meant Danielle refusing to be normalised, or expected to fit in within that space. In this respect, Danielle would be seen and heard as a member of this classroom with her needs met within and by the collective (Boger, 2023). This could mean being within a group of exclusively disabled people, away from the ableist gaze. Danielle spoke about finding the experience of being outside the mainstream empowering, as in secondary school there were less limits put on her by others with assumptions of her abilities.

- Can you think of any other strategies?

Empowerment

Empowerment can also be described as emancipation or participation:

Empowerment (E) is defined as the political process in which an oppressed or discriminated group forms a collective to gain power and raises the other voice that has been silenced and not listened to’ (Boger, 2023: 21).

Educators build relationships with their students. This relationship should be built on mutual trust and validation. Students need positive experiences in school, to feel believed in, and supported in their efforts to excel and to achieve. Özge describes her positive experience:

“I think for me it was in secondary school. Well, I don’t really remember a lot of primary school, but in secondary school, I had the feeling that my class teacher… she was believing in me, and like trying always to motivate me and trying to find ways in how I would understand the content of the subjects. And I had the feeling she was like really supportive and always telling me, you can do it and you will make it.”

Özge (Germany)

Marginalised people may or may not see their marginalisation as core aspects of their identities. However, due to others perceptions of marginalised identities, these identities can be suppressed or erased. More complex identities can be found, expressed and fostered through representation and empowerment. Danielle does not see cerebral palsy as the core aspect of her identity and explains:

“Cerebral palsy is only a small part of who I am. It’s not insignificant because without it, I wouldn’t be the person I am, but it doesn’t define me. I am also aware that other people, other disabled people, aren’t able to voice that. So I have a passion for disabled people in general to be able to embrace their own identity, whatever that might be, and to advocate for the fact that identity doesn’t need to be just an appearance.”

Danielle (Scotland)

- From above, have we thought about strategies the school could have used using the lens of empowerment paired with deconstruction or normalisation. Are there any others that you can think of?

- Can you think of times where empowerment would not be a good approach or may come into conflict with other perspectives?

Reflecting on Identity and Labelling in Practice for Teachers

During their school years, many students are grappling with the question of who they are, and this process can often appear overwhelming. Rather than labelling them, we should aim to structure and shape the classroom in a way that enables students to go through this process of self-naming independently.

We, as educators, have the responsibility to create a space where students are not discriminated against based on their identity. While we cannot guarantee that discrimination will never occur – as classrooms inevitably reflect societal structures thus reproducing discriminatory discourses and actions – we can work on raising our own and our students’ awareness of the complexities of identity. Through our actions, methods, and language, we influence the overall dynamic in the classroom, which can reduce discriminatory behaviour. One of our goals should be to create a learning environment where students do not feel pressured to identify with specific categories, groups, or communities, but where they have the freedom to choose to do so if they wish. Being labelled by others, especially by teachers, can be an inherently violent act, as it can strip students of their agency.

Labels often come with preconceived notions about students’ abilities. Their bodies and identities are already coded and constructed by outsiders – including teachers – before they even enter the classroom. This process is inherently biased and does not give all students an equal chance for fair treatment. Our identity is not solely defined by what marginalises us, but often, because of these marginalised aspects, others make assumptions about our capacities and our ability to be individuals. Consequently, these assumptions become part of the everyday experiences of discrimination that students face in schools.

In every classroom, there are students who experience this structural inequality due to different or overlapping aspects of their identity. To help these students build new narratives about themselves, educators need methods that show them that characteristics or skills society labels as deficits are, in fact, powerful resources. This is particularly true for multilingual students. Society often leads them to believe that growing up with multiple languages can have a negative impact on the language they use in school. However, the opposite is true: being able to understand and speak different languages provides students with access to diverse cultures, literature, and knowledge systems, making it a valuable resource. In order to support students in this way, it is crucial to get to know them well, to understand their unique needs, and to be aware of potentially discriminatory situations they might face. The need to empower students is crucial to providing them with the necessary tools to assert their identities and their self-worth.

Students have complex and nuanced identities, and some may want to label their experiences, while others may feel restricted by labels. Students benefit from feeling seen and valued, not just as marginalised individuals, but as complete persons, including their marginalised identity. Throughout their school years, students will explore their own identities, learning more about themselves and the communities they belong to or could potentially belong to. For some, these identities will be shaped by the norms of the communities they were born into, and as they grow older, they may begin to challenge these norms. It is important to question those norms and create space for students to explore their own sense of self.

As educators, we encounter emotionally charged situations on a daily basis, particularly when identity is involved. Identity touches the core of who we are – our sense of self, self-esteem, and personal beliefs – making these moments inherently emotional. The process of exploring one’s identity is not just social, but deeply existential. This is why such situations can be so intense. By recognising this, we can maintain composure and professionalism in these charged moments. Being “professional” does not mean being devoid of emotion; it means being aware of both our own emotions and those of the students, particularly the existential struggles they may be facing. Identity formation is not just a social process, but a deeply personal one, and threats to one’s identity can cause significant existential pain. Being mindful of this allows us to stay centered and offer the support students need during these crucial developmental moments.

Questions you could ask yourself as an educator:

- What actions am I taking to help students get to know each other better, and to foster a deeper understanding of each student’s individual background?

- Am I staying informed about political or societal changes that could impact my students and, in turn, affect the classroom dynamic? (For example, elections, issues affecting diasporic communities such as war or family living situations abroad, or incidents of racism, sexism, or queer and transphobic violence.)

- Do I feel unsure or overwhelmed when conflicts arise in the classroom, and struggle to find effective ways to address them?

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- How can teachers be questioning themselves and open while at the same time – have enough confidence and have tools to navigate the complex situations? (not one solution, but different…)

- How can we make sure educators refer to students by name and not by labels (administrative or self-constructed like stars-, sun- and moon-kids)?

- How can we ensure rights to support for students who need it without stigmatising them?

- How can we create a safer space for students to develop their identity with peers, while staying part of the school/classroom community?

Literature

- The language surrounding transgender and queer identities has been rapidly evolving over the past number of years. We have chosen to use trans or transgender without an asterisk. See here: Why We Used Trans* and Why We Don't Anymore for further information. ↵

About the authors

name: Sam Blanckensee

Sam Blanckensee (they/he) is a equality, diversity and inclusion practitioner based in Ireland with extensive experience in equality in Higher Education through their role as the Equality Officer at Maynooth University. Sam holds an MA in management for the nonprofit sector. Sam has worked within Irish LGBTQ+ organisations in voluntary and professional roles since 2013. Sam’s work covers a broad range of equality, diversity, inclusion and interculturalism initiatives including LGBTQ+ matters, gender equality, anti-racism, disability awareness and access for those within the international protection system. Sam is a non-binary trans person who is also neurodivergent and queer, All Means All is a project where the personal meets professional for Sam.

name: Özge Özdemir

Özge Özdemir works in extracurricular political education with a strong focus on anti-racism, anti-discrimination and empowerment. During and after her studies of political science and sociology in Frankfurt am Main, she specialised in working with young people and adults in educational work. Her activist experiences form the basis for both her practical educational work and her academic career.

name: Lina Render de Barros

Lina Render de Barros is a queer of color activist from Pernambuco and Münsterland. She completed her first state examination (teaching degree) and her master’s degree in bilingual European education at the University of Education in Karlsruhe and her master’s degree in sociology at the Goethe University Frankfurt. She researches, lives and works in Cologne, always with the aim of taking a stand against group focused enmity and contributing to a more peaceful coexistence.

name: Josefine Wagner

Josefine Wagner is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Education and Social Work at the University of Luxembourg.

She has completed several postdoctoral fellowships with a focus on inclusion and the origins of special needs education, including a visiting fellowship at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2020), at the Departments of Education and Anthropology at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth (2024) and the Department of Teacher Education and School Research at the University of Innsbruck in Austria (2021-2024).