Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Creating a Framework for Inclusive Learning Environment

Deirdre Forde; Chris Carstens; Cynthy K. Haihambo; Ulla Sivunen; Claire O'Neill; and Alessandra Galletti

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“At the start of the school year, I decorated my fifth-grade classroom myself—posters, window pictures, and laminated rules assigning responsibilities like sweeping, watering plants, and wiping the blackboard. But an issue quickly emerged: students only did their assigned tasks, ignoring anything beyond them. If the floor wasn’t swept because the responsible student was sick, no one stepped in. Three months in, I scrapped the system and replaced it with a single rule: “If you see a problem and can solve it, do so.”

It took time for students—fresh out of primary school and used to running to the teacher for every issue—to adjust. We had discussions about responsibility, perception, and helping others. As they adapted, they also began rethinking the classroom itself. If they were to take responsibility for the space, they should have a say in shaping it.

At first, their ideas were wildly creative and sometimes unrealistic. Financial constraints were also a reality at this low-income school. To teach accountability, I told them that before we could invest in new items, they had to prove they could care for the classroom as it was. Bit by bit, as they showed responsibility, I rewarded them with small touches—posters, carpets, plants.

Eventually, the class earned a small sum of money, which they voted to spend on two cream-colored armchairs. Many colleagues were skeptical, convinced they wouldn’t last a week. But because the students had made the decision, they took full ownership. The chairs quickly became the heart of the classroom—a place to gather, work, and relax.

Encouraged, we kept improving the space: a reading area that doubled as a mini home cinema, a picnic table for group work, a , a computer corner, and finally, a foosball table. I was hesitant about the foosball table—it was expensive and heavy—but the students insisted. So, I told them if they wanted it, they’d have to raise the money. They organized a falafel sale outside the school, handling everything from preparation to logistics. My only role was placing the order once they’d earned enough.

As the classroom evolved, it became more than just a learning space—it became a home. Students wanted to stay before school, during breaks, and after class. Instead of imposing strict rules, we made a simple agreement: “You can stay as long as your presence doesn’t interfere with someone else’s relaxation.”

To my surprise, this worked seamlessly. The students self-regulated, took responsibility, and showed that even in a school with limited resources, they could create something meaningful through teamwork and accountability.

This experience reaffirmed my belief: when young learners are given real responsibility—not just token tasks—they don’t just meet expectations. They exceed them.”

Chris Carstens, Werkstattschule, Germany

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- Why are there perceived barriers in creating inclusive learning environments?

- What needs to be addressed to make learning environments more inclusive?

- What is the importance of culture in terms of linguistic minorities?

- What is the importance of the curricular and sensory components of an inclusive learning environment?

- Is it solely the teacher’s responsibility to create an inclusive learning environment?

Introduction to the Inclusive Environment Framework

A group of teachers, advocates, researchers with diverse backgrounds, and other professionals worked collaboratively to design this chapter. It aims to answer some key questions about inclusive learning environments. The authors’ varied backgrounds and experiences of different learning environments adds richness and complexity to the shared content.

In engaging with this chapter, the reader should be able to:

- Have an increased understanding of the dimensions of an inclusive learning environment.

- Identify some barriers and enablers to an inclusive learning environment.

- Consider an inclusive learning environment through the lens of the learner and, in particular, through the lens of a bilingual deaf learner and a neurodivergent learner.

- Identify ways in which the inclusive learning environment framework can be used to enhance professional practice and learner experiences.

This chapter follows a similar structure to other All Means All Project chapters, beginning with opening questions that set the stage for exploration. The main body then delves into core content, while closing questions prompt readers to engage in reflective practice and support their ongoing professional development.

While collaborating on this chapter, we each found that we needed different elements from our environment at different times, which made it challenging to decide what to prioritise. As we worked to condense the complexities of inclusive learning environments into a single chapter, the scope of our task became clear. Readers may notice some variations in the chapter’s structure as we endeavoured to blend our perspectives on this multidimensional concept that lies at the heart of truly inclusive education. To simplify this complexity, we developed an inclusive environment framework, which we share here with the reader.

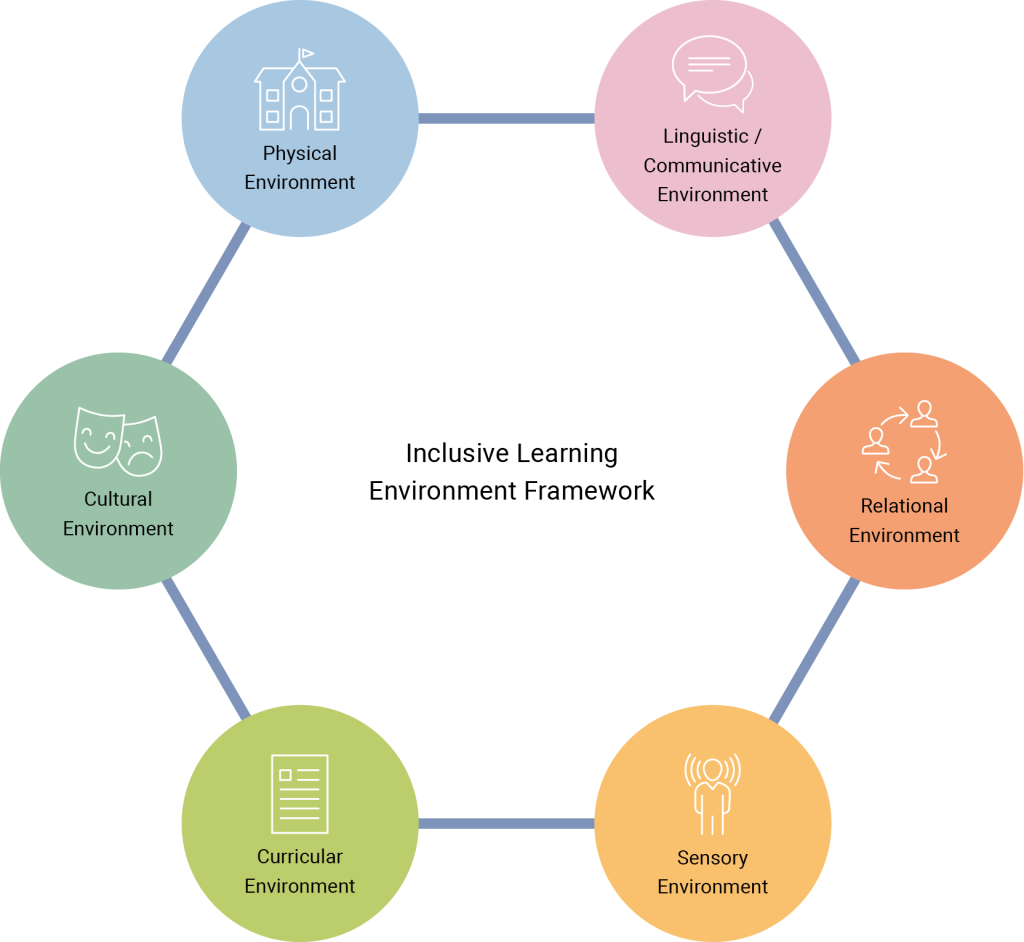

Figure 1: Inclusive Learning Environment Framework

When collaborating on this chapter, it became apparent that a framework was necessary to provide structure to this vast topic and the myriad ideas that we wanted to include. We share it with the intention for it to be a tool for teachers to plan, design, evaluate, collaborate, and reflect upon inclusive learning spaces. The components of the framework are physical, cultural, curricular, sensory, relational, and linguistic / communicative [Figure 1].

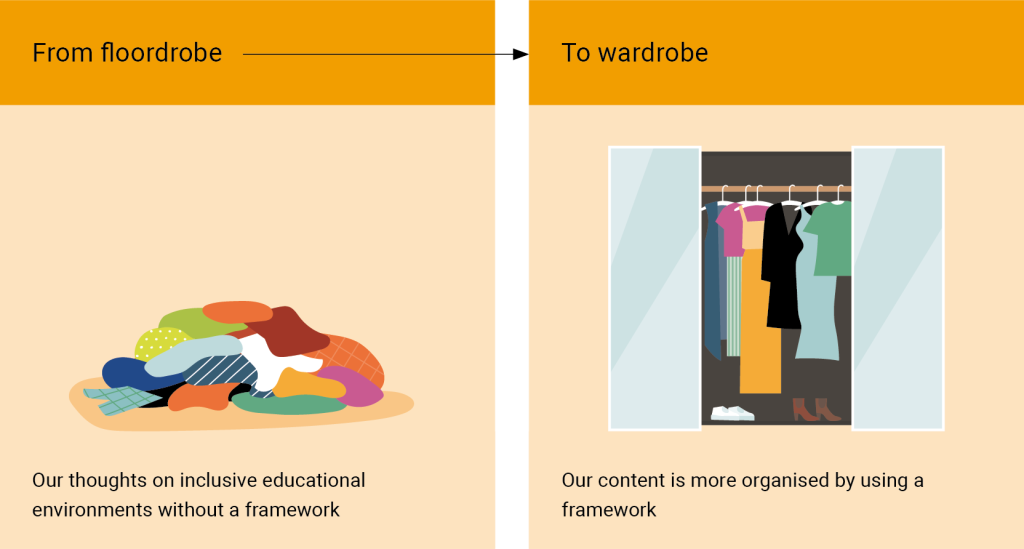

The analogy of a floordrobe or a chairdrobe [Figure 2] is helpful in explaining why to use a framework (Hargreaves, 2019). A framework can organise a work process into a streamlined, visually appealing, and organised “wardrobe”; the different framework components operating like hangers and shelves, organising ideas, and communicating written information in a structured way. Moreover, the visual representation communicates the interconnectedness of the six components, thus further emphasising the importance of fluidity of thought when conceptualising inclusive learning environments.

Figure 2: Using a Framework

Our diverse writing group needed to create a flexible space that accommodated each member’s individual differences, making the process of building an inclusive environment a kind of real-life case study. For instance, one author, whose neurodivergent thinking style and multilingual background influenced their approach, found visual representations helpful in organising collaborative ideas and information. Additionally, the group embraced significant linguistic and communicative diversity. To ensure accessible communication, we used signed language interpretation services, facilitating effective collaboration between a deaf author who uses Finnish Sign Language and the rest of the team, who do not use signed language. By adapting to each member’s needs—such as providing visual supports and sign language interpretation—the group embodied the principles of Universal Design for Learning and Inclusive Pedagogy. This collaborative approach provided multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression, resulting in an accessible, equitable, and inclusive working environment for all.

Frameworks are valuable tools that, like effective learning environments, help to clarify, organise, and support the learning process. Some alternative frameworks are included in the resources section of the chapter. The framework is offered here as a flexible tool to be adapted depending on the user, purpose, and context. Please make it your own.

We now turn to the six components of the framework. While the All Means All Project identifies thirteen dimensions of diversity, a detailed exploration of each is beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead, we focus on selected components through our own unique perspectives. We encourage the reader to use dimensions of diversity applicable to one’s context, learning environment or learners, as an opportunity to operationalise and individualise the framework.

- The framework has six components:

- Physical

- Cultural

- Curricular

- Sensory

- Relational

- Linguistic / Communicative

- Suggested Uses:

- Plan

- Design

- Evaluate

- Collaborate

- Reflect

- The framework is a living example of an inclusive environment in action.

- The components are interconnected and non-hierarchical.

- The framework is adaptable and flexible.

- Other frameworks are available and may suit the reader’s needs better.

Six components of the Inclusive Education Framework

Physical

The physical environment is conceptualised as a space that is socially produced through the interplay of objects, structures and actions (Aristarchi & Venini, 1985). School space is often perceived as a void by those who occupy it, something inherited and difficult to change, whose function is almost taken for granted: the theatre of the lesson, the still scenery of school life. Instead, it can be inhabited, adapted, transformed and made more compatible with the activities that take place there (even without making particularly onerous interventions). We can perceive it through our senses and interaction with the people and the furniture there. It can be smelled, touched, heard, seen, written on, scratched, soiled, stained, painted, moved, opened, closed, dressed, occupied, washed and covered. It can make one feel safe or in danger, sheltered or exposed, comfortable or uncomfortable. How a physical school space is designed and used can determine the extent of levels of participation and how successful social interactions are. In considering the processes of inclusion and exclusion, school spaces can exude a sense of welcoming and warmth where participation is a possibility for everyone.

It can indicate how to be used based on its conformation (Gibson, 1979). Space can increase levels of well-being based on how well it meets the needs of the people using it, thus it has the power to influence levels of inclusiveness (Kaplan, 1983). A clear pedagogical idea can be shaped through space design (Weyland & Attia, 2015) and therefore, the classroom environment is considered important in terms of influencing students learning and achievement and student attitudes (Vasquez & Oury, 2010).

Space can give information about itself, communicating where the resources one needs are located, through wayfinding (Lynch, 1960). Space, depending on its use, can enhance autonomous enjoyment and increase the perception of well-being. Perceived well-being provides a good basis for being able to increase inclusive practices (Cohen, 1980). In addition to providing equal use for all, it can be set up to serve as an interface for inclusive learning practices to make them more effective (Saffer, 2007).

The implication of space in the generation of exclusion is a topic in the international architectural, pedagogical, sociological and political debate (D’Alessio, 2012). The design and organisation of space can be elements that foster inclusion because accessibility can create inclusion or exclusion, and society is responsible for the exclusion of categories of people due to the presence of barriers within public space: it is society that makes people disabled, it is society that must adapt to people and not vice versa (Lettieri, 2008).

The awareness of school leaders is important in order to achieve the possibility of adaptive adjustments on the space, but the whole school community can also participate in this sense (Weyland & Galletti, 2016). If the whole school is conceived and designed to offer different opportunities for use – in compliance with inclusive teaching methodologies it could include places to work in small groups, places to work alone, places for meeting with the teacher, places dedicated to well-being and relaxation, spaces to be able to take different positions, informal spaces for discussion, open laboratories where one can try out what one has learnt directly, spaces to be used ‘autonomously’ by students (Caprino et al., 2022). Proposing a differentiated school environment can provide a good basis for responding to different needs, making the necessary adjustments according to individual situations, through the use of furniture. Alternatively, even small adjustments based on the organisation of the classroom and the outdoor environment can serve as a means to raise awareness throughout the school in the future (Weyland & Galletti, 2022).

To a large extent, the classroom environment is considered important in terms of influencing pupils’ learning and achievement, learner attitudes and their sense of belonging. The use of space by a teacher to ensure a sense of belonging is cultivated and whether learners are participating with their peers and fully engaged in learning is central to whether a child is included in a school or not.

In conclusion, when considering the inclusiveness of space, it is important to refer to the features of the actual people for whom this space needs to be inclusive. For the school, a Universal Design approach can help lay the foundations for an inclusive welcoming. The next step will be to adapt the space to individual needs, for which designers and teachers can define an intervention strategy with a multidisciplinary approach, where barriers to participation need to be removed. Spaces with glass partitions communicating to the classroom, bookshelves with wheels, whiteboards and movable screens, informal seating, shared and illustrated rules of use, orientation signs, furnished atriums for small group activities outside the classroom, are some of the elements that can positively influence the school’s possibilities for inclusive uses.

Cultural

In this component of the framework, we discuss inclusive school culture and the teacher’s role and responsibility in creating diverse and inclusive cultural environments. International mobility and digitalisation have increased linguistic and cultural diversity, and societal change (Blommaert & Rampton, 2011), which can be seen also in schools. UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (Stenou, 2002) states, that we need cultural diversity, because it is a source of innovation, creativity and exchange. Cultural diversity is part of common heritage of humanity and we as educators should recognise and affirm it: “As a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature. In this sense, it is the common heritage of humanity and should be recognized and affirmed for the benefit of present and future generations” (Stenou, 2002, p.4). For these reasons cultural diversity should be seen as an asset.

Inclusive school is about diversity of all people, including teachers and staff. When diverse learners see similar role models, they can identify with these adults and experience belonging to the school community as they are. All learners and adults get used to working with children and adults from a wide range of backgrounds. Diverse people create multicultural representations and cultural meanings that create a diverse and inclusive school culture with a sense of belonging.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of people with Disabilities (2006) emphasises the importance of diversity amongst the staff of a school: It states that in order to help ensure the realisation of this right,

“State Parties shall take appropriate measures to employ teachers, including teachers with disabilities, who are qualified in sign language and/or Braille, and to train professionals and staff who work at all levels of education. Such training shall incorporate disability awareness and the use of appropriate augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication, educational techniques and materials to support persons with disabilities.” (UNCRPD, Article 24)

An inclusive school reflects a democratic philosophy whereby all students are valued, educators normalise difference or diversity and a school culture reflects an ethic of caring and community (Baglieri & Knopf, 2004). Ideally, the school reflects the diversity of its surrounding society, like a mirror. In moving towards inclusive education for neurodivergent children, the response to education requires stakeholders to address the deficit disability discourses which permeate the system. What is needed is a willingness to examine attitudes and to challenge the status quo and commitment to collaboration among all stakeholders (Forde, 2022). In order to address deficit-based cultures, schools must empower neurodivergent and other children with diverse background by accepting and celebrating their diversity in thinking, feeling and communicating rather than making them ‘fit in’ or shape them into meeting ‘neuromajority’ or other majority norms. The Neurodiverse Paradigm, which is underpinned by a social model of disability is an alternative to deficit models of disability. It provides an inclusive and holistic world view that is welcoming of all kinds of minds and celebrates and values the differences inherent in humankind. Rooted in biodiversity and cultural diversity, the neurodiverse model recognises that different children need different support, and that society has a role to play in how ‘disabling’ a child’s impairments are. In this domain, education is an essential catalyst for achieving change and representation of disability must be at the heart of transforming integrative approaches to more inclusive ones (Forde, 2022). There is no more powerful transformative force than education to build a better future for all (Baglieri & Knopf, 2004). With the mobilisation of a neurodiverse model of disability, which is a radically different model of practice and antidote to the medical model of disability, comes the possibility of disrupting the normative of the current system, to expand it and create social change for neurodivergent children, so that they can occupy the system as valued members (Forde, 2022). Indeed such activism could be expanded to include all difference in mankind and to disrupt the status quo, thus including not just neurodivergent children but all children who do not fit the ‘norm’.

Curricular

As a student-teacher or a novice teacher, you probably have formed ideas about what a curriculum is. Most likely, you associate “curriculum” with the plan for academic content, including assessment. According to Stotsky (2012), “a curriculum is a plan of action that is aimed at achieving desired goals and objectives. It is a set of learning activities meant to make the learner attain goals as prescribed by the educational system. Generally, it includes the subjects and activities that a given school system is responsible for. Moreover, it defines the environment where certain learning activities take place. Furthermore, curriculum defines what happens in any formal educational institution, and no school or university can exist without it. The concepts governing curriculum are dynamic in nature because of the changes that occur in everyday lives” (p. XX).

The curriculum is broader than the formal document that comes from your education governing body and determines what to be taught and how it should be taught. It includes school cultures, the school spaces and approaches to teaching and learning. It includes activism to address attitudes towards diversity and to address exclusion. It may also involve the active movements to decolonise curriculums so that children can see themselves reflected in its content. The curriculum in schools is supposed to enable all children to acquire knowledge and skills that will help them become independent, socially- and emotionally sound, adaptable and productive citizens of their communities and countries. Marsh and Willis (2009) view curricula as all the “experiences in the classroom which are planned and enacted by the teacher, and also learned by the students” (p. XX). In this chapter, we describe curriculum as a plan of what should be learned and how it could be learned. It further entails who the learners are and how they can be enabled to learn through various means. We also consider who the facilitators of learning and socialization are and what values and attitudes they adopt to facilitate learning for all learners. The curriculum further entails the environment in which teaching and learning take place and how this environment is constructed and re-constructed to allow for creativity and diversity of learning and being.

We are writing this chapter from the perspective of inclusive education, with a deep belief that all children and young people can learn and should be enabled to learn irrespective of their diversity. Societies are diverse and so are schools. Learners in schools are different and so are their teachers. Some learners have typical needs and can perhaps learn through any curriculum presented to them. Others might have neurodiverse conditions that will require the teaching and learning environments to be adapted to suit their learning styles. Others could have sensory difficulties, social-emotional and behavioural difficulties, physical and cognitive disabilities. Some learners are gifted or talented in specific areas while others are from under-resourced families in which their most basic needs are barely met. Learners with migration histories might have experienced trauma; those from racial and religious minority backgrounds might be stigmatised and suffer emotional trauma and rejection. Learners who identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual, Transgender or Queer plus (LGBTQ plus) could experience repeated criticism, confrontation and labelling. Schools, through their curricula, have a responsibility to afford this diverse population of learners opportunities to experience belongingness, participate in learning and develop to their maximum potential, free from bias, ableism, prejudice, discrimination and stigmatisation. Please refer to the section on frameworks and ableism for a better understanding on the role of institutions of exclusion in schools and communities.

Most countries have adopted the learner-centered and competence-based curriculum models for their education systems. Unfortunately, academic achievement remains the most important measure and assessments remain rigid, without consideration for learner diversity. Learner-centeredness means child-centeredness. Child-centred means that the aspirations, potential and drive of each individual learner should be considered. Learners should be enabled to learn in the best way they can learn. An important part of learning is participation. We do know that learners are diverse with regard to physical, emotional, intellectual, linguistic, social, economic, sexual, racial, religious and personal development. Most curricular are developed for the typical learner and do not consider the diversity of learners. Teaching and learning happen in average classrooms, based on the ideal assumptions of the conventional learner who, in accordance with typical development, lives in a family that loves them; have at least two nutritious meals a day; sleep on a relatively comfortable bed; come to school content and find happy classmates and teachers that are excited to engage the learners. We do know that this picture is flawed. Around the world, children are excluded from schools because of dis/ability, race, language, religion, gender, and poverty. It is the duty of the curriculum to reduce biases and inequities in education. This is despite various national and international legislation and conventions which suggest that education is a right of every child and that every child should receive education that is suitable to their needs. These include the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Salamanca Declaration (1997), the Convention of the Rights of the Child (1990), the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) and many others. Globally, these international conventions have been domesticated and local policies developed to propel inclusive education and ensure that no child or young person shall forfeit their right to education by virtue of their diversity. However, millions of children across the world experience school as a hostile environment in which they are expected to fit in. Students can feel excluded in an education system when learning through a curriculum that is not friendly to diversity. While it is primarily the responsibility of school principals to create and oversee the implementation of inclusive learning environments, teachers have a key role to play as they deal with children and young people on a day-to-day basis and have deep insights into their classroom and school dynamics. Teachers should respond to diversity in a manner that shapes learners’ attitudes and influence their behaviours by addressing negative attitudes such as racism, stigmatisation and prejudice and rewarding good attitudes and behaviours. While policies at all levels of the education system can support and help create diverse learner friendly environments, curricula should be developed and adapted to suit the strengths and interests of learners in your class (Wood & Haddon, 2020,). An inclusive curriculum helps learners from diverse backgrounds feel relevant and valued as they feel more connected to the course material.

Learners feel more included and develop a sense of belonging within the school community when the curriculum reflects and celebrates their diversity. Moreover, when students leave their comfort zones and step out into the real world outside the perceived protective environment of school, they should be prepared to deal with other cultures and people from diverse backgrounds. An inclusive curriculum prepares them for this by exposing them early on to the different viewpoints, cultures and identities of people. It instils in students values such as open-mindedness, empathy and cultural sensitivity so that they are better able to adjust to different working environments. An inclusive curriculum incorporates the social and cultural aspects of the community it serves and includes locally relevant themes and contributions by marginalised and minority groups. By ensuring an adapted accessible curriculum, learners are enabled to succeed and are motivated to learn in a welcoming and safe environment.

Sensory

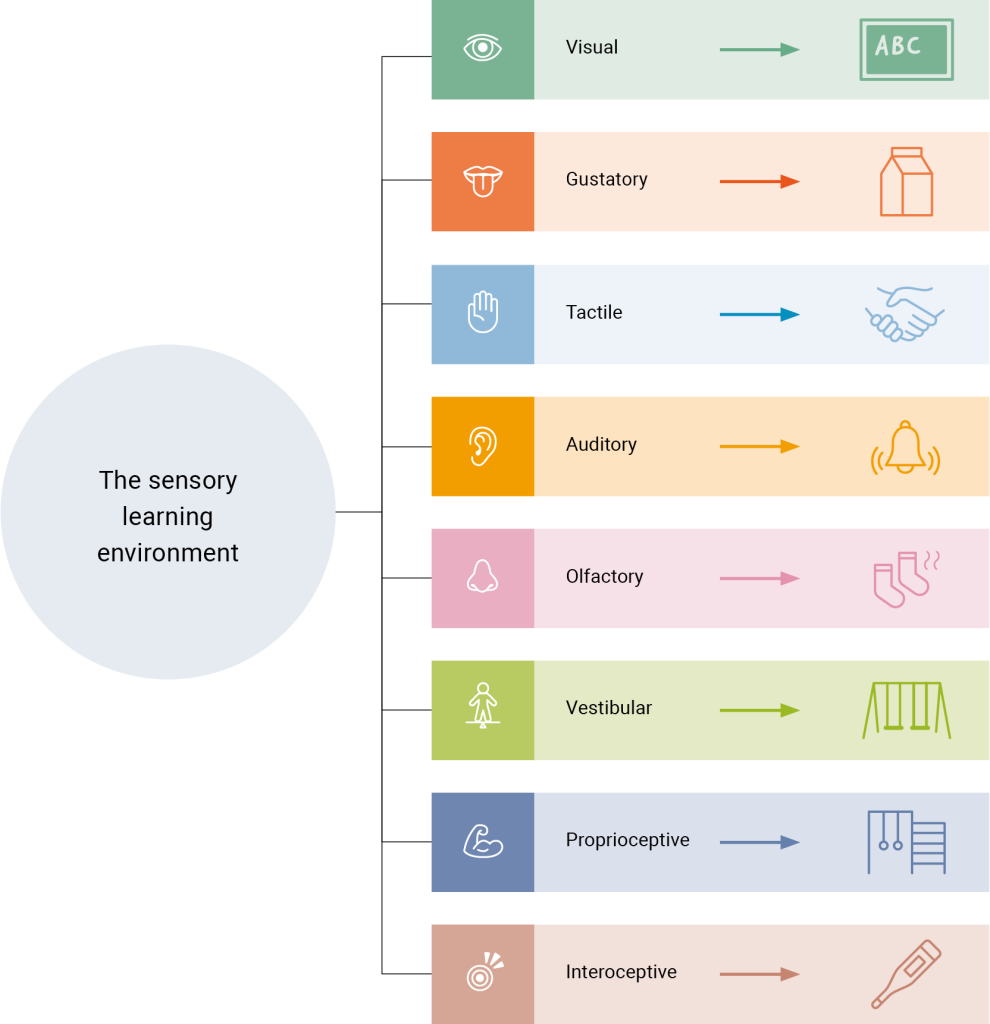

Figure 3: The Sensory Learning Environment

The sensory component of a learning environment has a significant impact on all its inhabitants and not only the learners. That being so, some learners, including (but not limited to) neurodivergent learners, may experience significant differences in how they experience the sensory environment. This interaction between the person and the sensory environment can impact not only learning, but also wellbeing. In this brief introduction to sensory environments, we will focus on neurodivergent users of the learning environment. We will also use the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to represent this information visually in diagrams and tables throughout the section. In addition, the resources section of this chapter includes a video related to this topic. It is important to note that this section is not offered as a comprehensive overview of sensory systems, processing, integration or regulation. That being so, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) from an Occupational Therapist (OT) with a neurodiversity-affirmative approach and a specialist in supporting sensory differences is highly recommended.

A Brief Overview of Our Sensory Systems

With that caveat aside, when supporting neurodivergent learners, we consider how the educational environment interacts with eight main sensory systems. Rather than describing these systems in a text-heavy way, we have instead used the table below to summarise some key points. The table can be used as an evaluative and planning tool to consider how the sensory learning environment can influence inclusion or exclusion in your learning space.

Figure 4: Making sense of the Sensory Learning Environment

Table 1: An explanation of Figure 4

| Sense | Where in Body | Consider in the Learning Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Visual – Sight | Eyes |

|

| Gustatory – Taste | Mouth, tongue and throat |

|

| Tactile – Touch | Skin, tongue and mouth |

|

| Auditory – Hearing | Ears |

|

| Olfactory – Smell | Nose |

|

| Vestibular – Balance | Inner ear |

|

| Proprioception – Movement and Sense of body in space | Muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint receptors. |

|

| Interoception – Internal | Nerve receptors inside and outside body |

|

In looking to theorise the interaction between the person and the sensory environment, there are many different avenues to explore. For instance, Merleau-Ponty (1962) considers the body as a key to understanding of our relationship to the environment that our bodies and sensory systems are immersed within. Overtime, the realm of theorising the individual’s interaction with their sensory environment has become a focus for Occupational Therapists (Ayres, 1972; Schoen et al., 2019). More recently a new wave of writing is emerging from neurodivergent individuals that explores the lived experiences of the users of these sensory environments (Milton, 2012; O’Neill & Kenny, 2023). What is clear from synthesising these different perspectives is that neurodivergent learners experience the educational environment in a highly embodied way. For example, challenging sensory experiences in the learning environment are frequently reported by autistic people (O’Neill & Kenny, 2023). The interaction between a poorly considered sensory learning environment and neurodivergent sensory systems can lead to overwhelm, distress, exhaustion, and significant health difficulties, including BIMS (burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown) (Phung et al., 2021).

In order to provide balance and not be overly deficit-focused, it is vital for us to share that inclusive learning environments can also offer experiences of sensory joy for all learners, including those who are neurodivergent. There is satisfaction in experiencing these occasions with learners. This reference to sensory joy, although effectively marketed by companies offering sensory products, is not as well researched. However, this topic is active and live in the folk knowledge within neuro-minority communities. The following is a mind map from one of our group members that represents the neurodivergent sensory joy they experience and observe in their educational environment.

Figure 5: Sensory Joy and Inclusive Learning

In practical terms what can we do as teachers to support learners who may experience the sensory environment of school in a different way?

- Firstly, include a sensory checklist in when completing environmental audits of your school and classroom. Ideally, a neurodivergent individual with some knowledge in this area would help assess the environment too. There are many checklists available and Gareth Morewood has developed checklists that incorporate learner voice (http://www.gdmorewood.com/author/gduser/).

- Get to know your learners and their sensory preferences and aversions. Some neurodivergent learners may have an occupational therapy report with recommendations. If you get the chance to collaborate with an occupational therapist in considering the sensory needs of learners in the educational environment, seize it!

- Be understanding of the fact that sensory preferences, aversions and sensitivities can change over time. Many factors both micro and macro affect these changes. Stress, rest and illness are but a few of these factors.

- If a learner is telling you (by their words or in another way, their behaviour for example) that there is something in the sensory environment distressing them, please believe them. Please do not invalidate their experience, for example, by saying “you’ll get used to it”. This type of invalidation can lead to learners not trusting their own sensory and body signals and this neither inclusive nor healthy.

- Be cognisant to create a low arousal environment. This can offer a retreat for a learner who is over stimulated.

- Please be sensitive, responsive and adaptive to the sensory needs of learners. In keeping with the principles of UDL, offer different sensory options in your classroom in the form of sensory toys, seating options and adjustable lighting and acoustics. Do not be overly-prescriptive with scheduled sensory breaks and sensory diets are not as inclusive as a person-led and flexible approach. A sensory break should not be offered as a reward and never withheld as a consequence.

Relational

Good relationships can have a deep impact on a child’s self-esteem, belonging, social functioning, academic success and resilience (Dooley et al., 2012). There is a plethora of research which shows that a high relationship quality between teachers and learners is one of the most important and effective ways to promote development, both socially and in terms of learning and achievement (Allen et al., 2018; Holzerberger et al., 2019; Pianta et al., 2012; Roorda et al., 2011). Two psychological theories are frequently used to explain the importance of high-quality teacher-student relationships: the attachment theory and the self-determination theory (see glossary) (Pianta et al., 2003; Roorda et al., 2011). In order to feel socially included, students should experience schools as reliable places of learning and support, which in turn is based on the quality of their relationships with teachers and peers. This is even more important for students with special educational needs (SEND), who are often more exposed to isolation and victimization (Murray & Pianta 2007). When good relationships at school are lacking, children can see themselves as outsiders, isolated from the school environment (Skinner et al., 2014). The fragility of student-teacher relationships has been brought into question now that many European countries are being influenced by neoliberal policy discourses and are dominated by the values of self-interest, individualism, competition and comparisons (Hall et al., 2019). With education coming to be more closely linked to economic growth and global competitiveness, there is an increasing emphasis on standardisation and out-comes based assessment, test-based accountability as well as corporate forms of school management. Thus, the tensions produced by the clash of conflicting philosophies that underpin inclusive learning environments and schools that narrowly focus on academic achievement over relationships means that while education is meant to be for all, education is becoming a commodity, a private good to be consumed. Neoliberal policy discourses shift the focus of teachers care away from students, as performative pressures on pupils and teachers are contributing to rather than ameliorating the marginalisation of pupils who do not fit the normative homogenous group of learners. Therefore, now more than ever, educators have a responsibility of care to all students and in Nell Nodding’s words “we should want more from our educational efforts than academic achievement and second, we will not achieve even that meagre success, unless children believe that they themselves are cared for and learn to care for others” (1984).

The concept of care refers to concern for others, responsibility for a relational caring (Noddings, 2002, 2012) and teacher care is defined as teacher behaviours which enhance or maintain the quality of positive interpersonal relationships among teachers and students (Bieg, Backes & Mittag, 2011). Teachers must put care at the core. Strong relationships with teachers and support staff create the foundation for inclusive education. Schools play an important role in providing a safe, caring environment for children and building connections and relationships with trusted adults. Relationships are central to children’s sense of belonging and well-being (Treisman, 2016). Promoting positive school staff relationships and supporting emotional well-being is paramount for teachers working to build deep relationships with students. One of the strongest predictors of stability and well-being, in young people, is the existence of at least ‘one good adult’ in their lives. Crosby (2016) emphasises that teachers can be a significant attachment presence for vulnerable students, a connection, who is safe and available to a child in their time of need. This good relationship can have a deep impact on a child’s self-esteem, belonging, social functioning, academic success and resilience (Dooley et al., 2012).

The role of the teacher in creating an inclusive learning environment is of key importance. Within the traditional systems of school culture and structure it is still widely believed that the role of the teacher within the school context is to teach and evaluate certain subjects as well as the pupil’s performance. There can be a lot of pressure to achieve certain objectives from the curriculum within a given time frame and this in turn can impact on other vital elements of successful and inclusive teaching. That however is only a fraction of what we need to be doing in order to truly make our schools inclusive. We would strongly argue that creating a welcoming and safe learning environment, is the foundation of any successful learning experience, enabling a child to participate and learn.

As demanding as the task of educating and caring for young learners may be, fortunately educators often have a lot of freedom in choosing our working methods, modelling and preparing content, or making changes to our work environment. This not only requires the critical reflection of our own presuppositions and biases but also the willingness to make an active effort in redefining teacher-student relationships and challenging the status quo in order to promote social change.

Elements of successful teaching and inclusive education

In order for us to gain a general understanding of what successful and inclusive education entails, we want to introduce the four elements which Naukkarinen (2018) proposes of successful teaching and inclusive education:

- Addressing the basic needs of the students

- Applying group dynamic skills

- A learner-centred approach to learning

- Striving for on-the-job learning and school improvement

Arguably, considering point one: addressing the basic needs of the students, children need infinitely more than having merely their basic needs met. According to Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs apart from the basic needs such as physiological needs and safety, children also require a sense of belonging and love, self-esteem and self-actualisation for them to really thrive. Being one of the most important attachment figures to interact with students on a daily basis, it is up to us to fulfil these needs on various levels (Naukkarinen, 2018).

The nature of a group within a learning environment is an important factor in order for children to develop social skills and learning, motivate them and help them form their own concept of self. Understanding a group’s specific dynamic, applying group dynamic skills, and assessing its emotional nature are responsibilities which ultimately fall to the teacher. The sense of home and belonging cannot solely stem from a space itself but also from the relationships, rules and boundaries of the people within it. Essentially home is where your heart is. Getting to know and respect the other group members with their individual needs, learning to take others’ perspective for the sake of better understanding them and feeling seen and validated as an individual, are equally important factors to feeling at home and welcome in a learning environment.

Balancing a heterogeneous group of individuals can be very challenging and overwhelming at times and often requires a certain skillset and amount of leadership (Naukkarinen, 2018). This does not however have to indicate an authoritarian and more traditional approach but is more about fostering a culture of showing respect, giving responsibility and encouraging critical thinking within the group. Especially the feeling of being taken seriously and being validated are aspects which are of great importance to young learners and are experiences which many of them remember and apply to other situations in later life.

Being validated, respected and represented are also vital and overlapping elements of a learner-centred approach to learning. We need to be representing the children’s lived experiences, their family backgrounds and topics which are relevant to them in everyday life so that their identity is validated in an inclusive school environment. In order to achieve that we need to give learners more autonomy and responsibility concerning school culture and classroom environment, and curriculum and subject matters. Of course, there needs to be a framework for these choices, but it is still often the prevailing practice to exclude children from these decisions and processes completely when we should be letting them take ownership of their learning and develop learner agency. This frequently makes it difficult for children to relate and engage (Naukkarinen, 2018).

In the beginning it may feel unfamiliar to hand over responsibilities and control to the rest of the group, especially since the traditional perception of the role of the teacher is often associated with authority, working alone and being solely responsible for the wellbeing and development of a group of young learners. While we will admit that it takes relationship building, group work and practice, we can promise that relinquishing some of that control and collaborating with the students on relevant factors of school culture eventually does pay off.

Figure 6: Principles of learner-centred instruction

For us to successfully fulfil the requirements of inclusive learning mentioned above, it is of primary importance that we are willing to strive for on-the-job learning and school improvement (Naukkarinen, 2018). Learning and improvement are terms which might suggest that there are workshops to be visited or scientific literature to be read in order to meet expectations and become better versions of ourselves. While those are of course valid approaches they are not always mandatory for moving towards our goal. A democratic school culture, collaborating with children and parents, cooperating with colleagues and actively reflecting upon our own belief systems are elements to incorporate into our everyday practice which can go a long way. Essentially, we invite you to reflect on and question your belief systems, to be explorative and curious and ideally let others accompany you on that journey.

Importance of teachers to be reflective and reflexive

Many people would consider teaching as being a calling more than simply a job. It undoubtedly has a huge impact and might arguably be one of the professions with the most potential to actually enact change – offering young learners’ inspiration, a positive outlook and encouragement to actively participate in society (Jones, 2009). Hansen (2001) indicates that it should be viewed as more of a ‘moral practice’ while Fullan (2013) additionally proposes that this moral purpose cannot go without “the skills of change agentry”.

That being said, ironically, in most parts of the world, school culture still remains a traditional and somewhat hierarchical work environment in which people tend to hold on to their familiar belief systems and find it hard to free themselves from conventional perspectives to actively promote social change. We limit ourselves by preserving structural and cultural features of school organisation, frequently making school a very inflexible environment unable or unwilling to adjust to the individual’s needs.

Reasons for this are possibly teacher’s defensive routines, retaining prevailing practices because they offer a sense of safety and control and thus undermining critical evaluation and constructive discourse (Naukkarinen, 2018). Being responsible for a group of young learners can be daunting to say the least and it is understandable for us to gravitate towards authoritarian approaches at times – essentially often restaging our own childhood experiences in school. The thought of relinquishing control or even power can be very unnerving because notions such as classical reward-punishment solutions for example are something familiar for us to hold on to. If we want to strive to fulfil Naukkarinen’s fourth element of successful teaching and inclusive education as mentioned above, it is imperative that we are inquisitive and willing to establish a new learning relationship between teachers and students since otherwise a constructive discourse becomes impossible.

So, how is it possible for us to implement Naukkarinen’s fourth element to strive for improvement and become explorative and more open minded? A good aspect to start off with is critically reflecting upon our biases, our mindsets, values and belief systems. A task which is more complex than it might seem especially since reflection alone is not sufficient unless it is put into action. We need to be willing to make necessary changes and apply and incorporate them into our understanding of the world and our role within the microcosm of school. Mezirow (1991) suggests, that teachers need to be engaged in critical reflection of their experiences, which in turn leads to a perspective transformation: “Perspective transformation is the process of becoming critically aware of how and why our assumptions have come to constrain the way we perceive, understand, and feel about our world; changing these structures of habitual expectations to make possible a more inclusive and integrated perspective; and, finally, making choices or otherwise acting upon these new understandings” (Mezirow, 1991, 167).

As heterogenous as our learners may be – due to the implementation of inclusive school systems all the more so – teachers are still more often than not part of a majority group. Being subconsciously biased and having prejudices or presuppositions about others is human even for the most open minded among us. Suttie (2016) suggests four steps to reflect upon and fight our own biases including the cultivation of awareness, working to increase empathy and empathic communication, practicing mindfulness and loving-kindness and developing cross-group friendships in our own lives.

Psychologically prejudices often serve the purpose of making quick judgement of a group or situation thus helping us make decisions and react accordingly. It is a part of human behaviour which we cannot simply shake. Our biases become a problem if we are not aware of them or their impact upon others: “Teachers are human and therefore influenced by psychological biases, like the fundamental attribution error, when we assume that others who behave in a certain way do so because of their character (a fixed trait) rather than in response to environmental circumstances” (Suttie, 2016). Especially learner’s behaviours which are perceived as problematical or children who are frequently referred to as “difficult” are often sending a clear message and may be displaying a very rational reaction to very inappropriate circumstances.

Empathy in this case refers to our willingness to take another person’s perspective. That itself is not always an easy matter and requires us to develop an understanding for our student’s backgrounds, communities and their everyday life. We need to actively communicate and learn more about each other in order not to be blinded by our own stereotypical views. Not only does this help forge a more profound bond with our students but it certainly has a huge impact on school culture in general.

Practicing mindfulness in our job and everyday routines undoubtedly helps us better manage our own emotions and stress levels thus impacting our reactions to certain situations in the classroom. Suttie (2016) goes on to suggest that decreasing stress levels of teachers can also indirectly reduce their bias additionally to having a positive influence on their wellbeing.

Developing cross-group friendships outside the workplace does not only have a positive effect upon our relationships within the classroom but can also have a great effect upon a community as a whole. It is of vital importance for us to understand that neither our school nor our students exist within a vacuum but are closely linked to their surrounding environments and communities which makes it all the more important for us to reach out thus decreasing our prejudice towards outgroup members. Additionally, this is a major part of the teacher as a role model and can have contagion effects on our students and how they perceive the world since young learners are much more likely to do what we do than to do what we tell them to (Suttie, 2016).

As important as awareness and reflection on us may be, the positive changes that teachers from minority cultures can bring to a school environment are well documented. Not only can teachers of minority groups serve as role models but also as advocates helping students identify and make a connection between their lived experiences in school and at home (Pellegrino, Bransford & Donovan,, 1999). Villegas and Irvines (2010) found that teachers from ethnic minority groups, for example, managed to successfully establish helpful bridges to learning for students who might have otherwise remained disengaged from schoolwork. Such culturally-relevant practices, if used widely in schools, hold potential for reversing the persistent racial/ethnic achievement gap. Here too the awareness and reflection however are not enough and the presence of teachers of minority groups alone is not sufficient to change a school’s climate. They need to be willing to draw upon their own lived experiences working with and educating students and colleagues alike (Villegas, Strom, & Lucas, 2012).

Linguistic and Communicative

Inclusive multilingual education

In this chapter we discuss inclusive education from the view of linguistic and communicative environment, that consists of multilingual learners, linguistic minorities, and accessible communication, especially for the deaf and hard-of hearing (DHH) learners.

Every school is a rich language and communication environment with its diverse people, traditions, and cultures in a globalised world. Open discussions about the diversity of individuals and their diverse needs, the visibility of diverse people, among pupils and the staff, in the school environment is essential also from this point of view. Discussions about language awareness and linguistically responsive classroom pedagogy have become a permanent part of the normative framework of basic education (Piippo et al., 2021.). When we talk about minority and multilingual learners, we automatically approach the subject from the perspective of multilingual education in the field of pedagogy and language education. The school is a key institution for language socialisation (Ochs & Schieffelin, 2012), which gives teachers, educators and curriculum work a central role when building spaces for participation and language learning. Inclusive methods, materials, and digital environments in the learner’s first or heritage language, especially in small minority languages, can support the development of individual’s multiliteracies and well-being. Media, digital learning materials and interpreting services as examples of resources are good tools to promote multilingual learners and young people’s linguistic agency, participation, and access to their first language(s).

A minority/heritage language speaker or signer must learn the majority language in order to succeed well in the society. Using the student’s own linguistic resources contributes to the learning of other languages and multiliteracies. Inclusive multilingual education consists of managing learning environments in a way that supports learners’ language learning and linguistic-cultural identity also in their first/heritage languages. It can mean, for example, collaborative teaching, peers, and adults using the same minority/heritage language, translanguaging, using multilingual media materials, teaching each other and linguistically sensitive curriculum planning (more examples and solutions for teaching are described in the chapter → “Language Learning for All”).

Linguistic accessibility in learning environments and values for communication

There has been more awareness about accessible information and communication, especially during the COVID-crisis due to the visibility of signed language interpreting, and the growing number of subtitles and multilingual information in the media. Linguistic accessibility and linguistic-communicative environment are a kind of umbrella concepts that applies to many different groups of users. Below we give some examples of different user groups and solutions to apply also in learning environments.

Most people communicate through an auditory-oral-modality and traditionally services and education have been built around this way of communicating. For visually oriented people, such as deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) learners, as well other diverse learners’ multiple use of semiotic resources is important for accessing information and communication. For example, deafblind people communicate in a tactile way and therefore information should also be carried in tactile mode.

Simplified language is useful for people with cognitive challenges or for immigrants and second language (L2) learners making language more readable. For DHH people, visual and multimodal communication, language concordant communication, signed language or text-based interpreting and translation services removes communication barriers, supports learner’s multiliteracies and their participation.

There is plenty of normative expectations about a language and its norms. One example of norms concerns distantism, which constructs the ideal human being “as a rational and literate being, whose sensual engagement with the world is through eyes and ears” (Pennycook, 2018: 71). However, deaf, deafblind, and neurodivergent learners often use more semiotic resources and multimodal means creatively such as gestures, touch, and drawings in addition to language (De Meulder et al., 2019; Snoddon, 2022). Snoddon and Paul (2020) argues that access to a language should be framed as a health need especially with DHH learners in their early years, because language deprivation causes deleterious effects on cognition and emotional development. Language deprivation often occurs among those DHH children who were not offered a signed language (Snoddon & Paul 2020). Also, The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) supports the recognition of DHH children’s right to a signed language.

For hard of hearing learners who use spoken languages and benefit from hearing aids, learning environments can be designed in many ways to create a better listening environment. Sound-absorbing structures and many technical solutions make listening easier for these learners, and a better listening environment is more comfortable for all other learners too. There are various hearing solutions that can build a better hearing environment in class or at school. Traditionally there have often been arrangements on optimal listening conditions, but constant dependency on the learner’s weaker sense can be stressing for the DHH learner (Kiili & Pollari, 2012) causing hearing fatigue. Visual methods, speech-to-text, or national sign language interpreting services are very important and needed for the DHH learner but serve also peer-to-peer communication in a way which is not dependent on the degree of hearing.

Interpreting services are vital ways to make communicative situations more equal and accessible when thinking about the participation of all minority language speakers or signers, especially from the view of DHH people who use a signed language of their country. Interpreting service grants access to contents, gives diverse learners a chance to understand given information also in group level, express themselves with confidence and to build relationships with other people.

Access to interpreting services varies greatly from country to country. In the Nordic countries, for example, interpreting service is free of charge for users with disabilities. In Finland and Norway, public interpreting service for persons with disabilities is planned to be always available, both at school, at work, or in free time, and for studies or work abroad. Interpreting service can be delivered between a national sign language and national or other spoken language, or as speech-to-text-interpreting, and other more specified ways.

In an inclusive education and learning environment, both spoken and signed languages are seen as equal languages, as well all other diverse learner’s use of appropriate means and formats of communication that diverse learners might use, which requires various measures.

When discussing linguistic and communicative environments in schools, all learners benefit from a learning environment where communication and interaction is multimodal. Educators should therefore explore the means and tools available to ensure accessibility of the environment and communication.

Conclusion

Often the focus in school lies on the perceived responsibility of changing the learner or the content and curriculum, not so much on modifying the learning environment or reflecting upon ourselves. Our approach to these situations often lacks reason, since we would hardly change, much less become irritated at a plant for failing to grow but would try to devise ways to adjust the environment in which it is growing. That responsibility ultimately falls to us as teachers being the primary attachment figures for our students and key figures within the school context as well as playing an important role in bridging the gap between school and society as a whole. Achieving that goal requires the willingness to question our values and belief systems, taking other’s perspective and constantly striving to improve school, making it a more welcoming and safer place for all of us. Teachers committed to fostering inclusive learning environments will listen to neurodivergent professionals and neurodivergent learner voices when conceptualising, designing, planning, using, and evaluating sensory spaces and places (Neilson, 2021). Actively building a school environment which provides a sense of belonging and feels like home is not only essential for our own wellbeing but also for that of our students. Meeting all those requirements is undoubtedly a major challenge, it is however one which we do not have to face alone. It is important for us to redefine teacher-student relationships and invite parents and other stakeholders to actively participate in the journey. School is often a microcosm which excludes the environment that surrounds it. If we manage to make schools more welcoming and open places for everybody that will not only have a positive impact on the learning environment itself but in turn can be an important factor in making a change in society altogether.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- What is your personal definition of an inclusive learning environment? In considering this question, think about the vital components of an inclusive learning environment.

- Please take one of the other 13 dimensions of diversity. Use this as a lens to explore the inclusive learning environment framework.

- Compare the framework used in the chapter with some other conceptual frameworks that you are familiar with.

Literature

Resources

A video on sensory supports: https://t.co/1LwEjXwkWX

A basic guide to the eight sensory systems discussed in the chapter: https://sensoryhealth.org/basic/your-8-senses

Gareth Morewood’s Sensory Checklist for Schools – http://www.gdmorewood.com/resources/sensory-checklist-for-schools/ (Accessed, 16th September, 2022)