Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Inclusive Play: Norm Creative Approaches to Transform Integrative Play to Inclusive Play

Deirdre Forde; Sebastian Nemeth; Dean Vaughan; and Georga Dowling

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

This is an example from a Danish school:

“It is a regular school day in a school-class for children between 8 – 9 years old. Thilde, one of the children, has just started in the class, as she moved from another school. After having their lunch, they are all sent out to the playground. Thilde asks her new classroom teacher if she (the teacher) is also joining the class outside. The classroom teacher replies “No, but Helle (another teacher) is outside at the school playground.”

Thilde makes it out the door and not that long after, another child approaches the classroom teacher while holding Thilde’s hand. Thilde is visibly crying. The classroom teacher asks Thilde “Why are you crying?” and Thilde explains that she couldn’t find any adults and it was very noisy outside. The classroom teacher reaches for Thilde’s hand and takes her, outside to the playground. Here on the other side of the building, in the shade of canopies, a few of the adults are standing. The classroom teacher explains: “There’s always an adult present here.” And Thilde nods. Helle, one of the other adults, goes to the playground with Thilde and participates in a free play-activity by the sandpit. The bell rings and Thilde goes back inside.

The next break Thilde is outside again, and she is looking around for an adult. The adults outside have changed to another group and there is no one she recognizes. A few minutes later, one of the children comes into the teacher’s room with Thilde, looking for her classroom teacher. Thilde is crying and the classroom teacher once again shows her where the adults are standing, then tells her, that there’s always adults around here, and no one is leaving her alone. Then the classroom teacher leaves Thilde at the playground. After this, Thilde is no longer observed participating in play at the playground, she walks around the corner of the play-area and for a few weeks has little to no interaction with any of the adults.”

Initial questions

There are several questions that we pose to unpack what is happening within the scenario above.

- What is play?

- What is inclusive play?

- How might a teacher foster inclusive play?

- How can we create a culture of inclusion and participation?

- What are the effects of exclusion from play on children?

Introduction to Topic

Play has been at the heart of children’s learning for many years and the learning potential rooted within play in terms of social and cognitive abilities is routinely recognised by scholars and theorists from around the world (Ginsburg, 2007; Hayes, 2013; Hayes & Filipovic, 2018; Moore & Lynch, 2018). Understanding that children have individual needs, views, cultures, and beliefs that deserve to be listened too (UNCRC, 1989), is imperative to ensure children develop positive self-identities (NCCA, 2009).

The notion of inclusion should not be viewed in isolation, but together with autonomy, participation, rights and listening to the voice of children (Clark & Moss, 2005; Lundy, 2007). The concept that knowledge is socially constructed is integral to the notion of a children’s rights-informed approach to participation (Lundy & McEvoy, 2012). Children’s meaningful and authentic participation is fostered through the implementation of rights-based approaches (Byrne & Lundy, 2019) that are responsive to the increasingly diverse cultural and social worlds we live in (French & McKenna, 2023; O’Toole, Walsh & Kerrins, 2023). Teachers are constantly adapting to the ever-changing landscape of their classroom and the needs of each diverse group they teach (Brennan, 2012; French & McKenna, 2023). Children learn these skills through a playful environment (Hayes, 2013; Hayes & Filipovic, 2018; NCCA, 2009). Play, and especially inclusive play, is a vehicle to meaningful participation for children (Hayes, 2013).

Key aspects

What is play?

Play is the highest stage of the child’s development at this time; for it is a freely active representation of the inner . . . It produces, therefore joy, freedom, satisfaction, repose within and without . . . (Froebel, 1885: 30)

Anthropologists have studied play throughout the centuries and there has been evidence of children telling stories, playing games, and dancing in the most primitive of eras (Flood & Hardy, 2013). Plato was a big believer in the value of children’s play and even offered advice to mother’s on promoting playful approaches at home (Flood & Hardy, 2013). Plato also believed that the experiences children had in early childhood have a lasting impact on their final development leading into adulthood. Friedrich Wilhelm Froebel and his philosophies have not only contributed to the development of many play-based programmes globally but through his gifts and theoretical workings he exemplifies investigative and experiential play opportunities while maintaining the theme of unity within his philosophy (Bruce et al, 2019). Unity in the sense of play practices that cater for the wide variety of needs within our education settings (Bruce et al, 2019; Froebel, 1885).

Defining Play

There are several definitions and understandings of play. Play has been at the heart of children’s learning for years and open to interpretation and scrutiny from many theorists’ perspectives (French, 2018; Pyle & Danniels, 2017). Therefore, it is extremely difficult to narrow the philosophy of ‘play’ into one succinct definition.

Play-based learning has been described as a teaching approach involving playful, child-directed elements along with some degree of adult guidance, and scaffolded learning objectives (Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2013). It is moulded in Vygotskian and Froebelian theory where a socialist approach to teaching and learning is encouraged and teachers facilitate new ideas and knowledge within a modelled and purposeful framework of play (Vygotsky, 1987). Rather than offering a universal definition, contemporary literature on play and play-based learning draws on multiple perspectives regarding its complexity (Bubikova-Moan, Hjetland & Wollscheid, 2019), which includes, but is not limited to: play and whether play-based approaches translate into meaningful learning for children (Brooker, Blaise & Edwards, 2014), the content within play and distinguishing between different play types (Vorkapić & Katić, 2015), the importance of role-play (Bonilla-Sánchaz et al., 2022), the role of the adult during play (Hayes, 2013; Loizou & Loizou, 2022; Pyle & Danniels, 2017), compatible assessments (Pyle & DeLuca, 2017; Pyle et al, 2022) and what we will explore throughout this chapter; inclusive play (Danniels & Pyle, 2022).

For the purpose of this chapter, we are looking at inclusive play through the lens of the classroom and the school community. What does inclusive play look like in the classroom and how can we promote it within our teaching pedagogy?

Inclusive Play

When inclusion is being considered within a classroom there are two main schools of thought: academic inclusion and community inclusion (Goransson & Nilholm, 2014). That is how we, as teachers and educators, support the inclusion of children with diverse needs on an academic level and on a community level. Viewpoints and understandings of this differ greatly within the teaching communities (Danniels & Pyle, 2021). Kruse and Dedering (2018) posit that differing views of the conceptualisation of inclusion leads to the implementation of alternate inclusive teaching strategies. Now, with more and more children with diverse needs attending mainstream school (Gottfried & Kirksey, 2019) teachers need to unpack what their understanding of inclusion means.

Play is espoused as a sacred right of childhood, as a way in which young human beings learn to be happy, mentally healthy human beings (Cannella, 2008). Inclusion refers to the social justice principle that all children, including children with disabilities, belong to the school community and are entitled to share in all the social and academic opportunities a school has to offer (Fleisher & Zames, 2001). An inclusive environment where equality is upheld and diversity is respected is fundamental to supporting children to build positive identities, develop a sense of belonging and realise their full potential (DCYA, 2016).

There is a necessity to provide opportunities for all children to thrive through the promotion of positive identities and abilities, the celebration of diversity and difference and the provision of a participative culture and environment (Ministry of Education, 2017; NCCA, 2009). Thus, research shows that it is imperative that play, as a social opportunity afforded to children, underlines the right of every child, regardless of their ability or culture, to participate, in a way which ensures that their sense of identity is affirmed, so that all children can be happy and healthy mentally (Bruce et al, 2019; Flood & Hardy, 2013; French, 2018; Moore & Lynch, 2018). There are three fundamental components that we believe need to be present within an inclusive classroom: a desire to ensure children’s rights are upheld (UNCRC, 1989), the need for children’s voices and agency to be central to the curriculum (Ministry for Education, 2017; NCCA, 2009) and the culture of the classroom to be one that embodies inclusivity (DCYA, 2016).

Frameworks that support inclusivity in the classroom

A dialogical framework

Throughout this chapter we will dissect different frameworks. We will begin by reviewing inclusive play through the lens of a dialogical framework (Alexander, 2020) while placing children’s voices, right, and agency at the centre of their learning (NCCA, 2009; UNCRC, 1989). A dialogic framework utilises the power of talk to allow children and teachers to unpack and make sense of the topic they are discussing (Mercer & Hodgkinson, 2008). Through dialogue and communication, the children are making sense of the world around them (Alexander, 2020; NCCA, 2009) and the teachers are learning how the children understand and disseminate the information (Alexander, 2020). This sparks an interest in learning (Mercer & Hodgkinson, 2008), higher-order thinking (NCCA, 2009), encourages social and emotional skills through democratic engagement (Alexander, 2020) and empowers life-long learning (Mercer & Hodgkinson, 2008). This coupled with the use of a multimodal curriculum allows for jointly constructed knowledge within a classroom setting (Alexander, 2020; Mercer & Hodgkinson, 2008).

Play can be self-directed, child-led, child-centred or guided by an adult, but the critical importance of these approaches is that the child is at the centre of the learning experience (Baker, Le Courtois & Eberhart, 2023). Teaching, especially in early years education has shifted from a traditional didactic form of teaching where the teacher stands at the top of the classroom to a more holistic and inclusive dialogical approach where children’s agency is respected and valued (Tovey, 2016). Dialogical perspectives originate from the idea that knowledge can be co-created, ideas developed, and misunderstandings overcome through teacher and student collaboration (Alexander, 2020). Developing this agency in a learning context fosters important attitudes and values towards learning such as motivation and self-regulation (McClelland & Cameron, 2011). Play allows children to experience agency in their learning through “participation, willingness, and endorsement” (Baker, Le Courtois & Eberhart, 2023:373). Learning through a dialogical framework is a playful process where children have agency to be active participants in their learning journey (Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, 2011).

We argue, for the purposes of meaningful inclusion, this dialogical framework needs to be expanded to include the parents/guardians of the children. Their funds of knowledge will allow for a deeper understanding of the needs of their child and could, therefore, enhance the child’s learning. We also believe, for the purposes of inclusion, that dialogue could be interpreted as communication. The spoken or written word are not the only vehicles through which children communicate their thoughts and understandings to us (Clark & Moss, 2011). Children also communicate through drawings, facial cues, and expressions. Therefore, for the purposes of this chapter, to conceptualise the concept of ‘dialogue’ and reframe it to meaning ‘communication’ would be more inclusive.

The capabilities approach

The capabilities approach highlights people’s capabilities and functioning’s (Nussbaum and Comim, 2014). It emphasises differences and builds on the understanding that difference is part of human diversity (Reindal, 2009; Reindal, 2016). Difference is not something to ignore, instead it is something to highlight through a capabilities lens. By acknowledging what children are capable of, ensures that strategies can be put in place to support these developing capabilities with human dignity (Unterhalter & Walker, 2007). This allows teachers to provide inclusion within their classroom. By acknowledging capabilities, and using this knowledge to implement strategies, teachers can support inclusion within the classroom. The capabilities approach encourages teachers to look beyond merely the physical capabilities but also uncover the broader holistic diverse needs of the children (van Engelen, 2021). Inclusive play involves children meaningfully participating socially, emotionally, and physically in all activities undertaken within the classroom (van Engelen et al., 2021). The necessity to focus on a broader holistic view of children with diverse needs in play is pivotal for teachers to look beyond the physical environment as the only barrier to inclusive play (van Engelen et al., 2021).

Making play inclusive can provide enhanced opportunities to build upon sensory, motor, language, relationships, coping and emotional skills (Fjøftoft, 2001). Through the exploration of social situations and self-expression children learn to understand the world around them (NCCA, 2009). Ensuring all children are included in these play activities helps children to unpack feelings and emotions and understand social norms (van Engelen et al., 2021), thus encouraging children to connect on an emotional level (French, 2018; Hayes, 2007). When play is made inclusive it encourages a social play culture to exist. The capabilities approach encourages teachers to highlight that social and attitudinal barriers can impact on inclusivity in spaces where physical inclusion exists (Barron et al., 2017). Being aware of these dynamics means that teachers can question the normative culture of their classroom on a structural level (Nussbaum & Comim, 2014).

There are tensions between inclusion strategies and marginalisation strategies and the prevalent strategy tends to be one that is deemed the cultural norm within the school (Berg, 2013). Berg (2013) uncovered another tension when examining teachers’ narratives on inclusion. This is the variance between the individual beliefs of teachers and the collective ‘agreed’ response to inclusion within a school.

According to Nussbaum and Comim (2014), capabilities are the actual possibilities to realise and gain access to functionalities in life. Capabilities within our approach in inclusive play refer to the actualised possibilities for accessing and participating freely and fully in play.

By viewing a child’s position through a capabilities lens, helps to identify how the child can be supported through play within the classroom, ensuring that no child becomes marginalised or misdirected from the normative playfield. Not because they are not invited into play, but perhaps because they do not have access to the capabilities, that are required from the structures formed around the normative playfield.

Children’s right to play

The elusive nature of play makes it difficult to conceptualise succinctly (Bonilla-Sánchez et al, 2022; Danniels & Pyle, 2022; Hayes, 2013; Loizou & Loizou, 2022; Pyle & Danniels, 2017; Pyle & DeLuca, 2017; Pyle et al., 2022). What is agreed upon however, is the learning potential rooted within playful approaches in quality educational settings (French, 2023; Hayes, 2013). Even at a young age, children have a pre-dispositioned preparedness to learn (NCCA, 2009) and this cognitive cycle and learning stems from generating knowledge from the world around them and experimenting with various ideas and concepts that allow children to explore their own identity (Tovey, 2016).

Children have a right to play and explore the world around them (Brooker & Woodhead, 2013; Lester & Russell, 2010; Paya Rico & Bantula Janot, 2021). Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the child (UNCRC) states that every child has the right to “rest, leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts” (CRA, 2010: 29). Play has transitioned from an informal activity to pass the time to an educational mechanism through which to drive meaningful learning (Tovey, 2016).

There is a direct correlation between Article 31 of the UNCRC, the right to play, and the general comment on the rights of children with diverse needs issued by the United Nations (UN) where it highlights full inclusion and playful approaches as a means of children with disabilities to feel included and respected no matter what the setting (CRA, 2010).

Lundy’s (2007) model of participation for conceptualising Article 12 includes four key elements: space, voice, audience, and influence. Bae (2012) posits that to ensure Article 12 is upheld teachers need to provide more than the tokenistic choice for children. Instead, they need to create relationships through deep and meaningful communication strategies for and with the children. She believes that this transparent communication between the teacher and the children will create a “democratic atmosphere that will enhance participation” (Bae, 2012: 66). We argue that this ‘transparent communication’needs to continue to the wider community of the classroom and include the main stakeholders that advocate for the child (their parents/guardians).

We propose that the main outcomes of inclusive play for children are an increase in their autonomy, agency, rights, and participation. Therefore, increasing an inclusive culture within the group, and elevating the sense of belonging, and well-being through peer-to-peer relationships and genuine involvement within a group can support inclusion. Hence, the need for inclusion to be viewed through an academic lens and a community lens are imperative for inclusive teaching strategies to have a genuine impact.

This leads to unravelling another layer of inclusion: children’s right in play. There is a plethora of literature relating to children’s rights to play and the need for play within an educational setting as a vehicle to enhance learning and meaning making for children (CRA, 2010; Lester & Russell, 2010; Lundy & McEvoy, 2012). However, we argue that for children to have the right to inclusive play the discourse on children’s rights in play needs to be explored.

Children’s rights in play

Play is publicised as being an optimal learning context for typically developing children, however, discussions around play and our more diverse learners are progressively negative (Danniels & Pyle, 2021). Some children with more diverse needs may choose to engage in more solitary play and less cooperative play than their peers (Lagerlöf, Wallerstedtand & Pramling, 2022; Olsen et al., 2019). If children do not have the capabilities to engage in more co-operative play, then their right to play is still upheld but their right in play is not.

Children who exhibit social isolation, may not be as accepted into peer-to-peer friend groups within the classroom (Kasari et al., 2011). Furthermore, children with English as an additional language tend to make fewer friendships in native English classes when not afforded the opportunity to engage in playful ‘children’s talk’ (Lagerlöf, Wallerstedtand & Pramling, 2022). The way some children with diverse needs play may differ from a typically developing child and these needs should be noticed, discussed, and utilised as funds of knowledge to further support all children (Barton, 2016; Messier, Ferland & Majnemer, 2008). The capabilities of children to interact, make friends, and socialise with their peers may be hindered due to their diverse needs. Therefore, the opportunity to play may be available to them, but their experience in play is not inclusive.

They may not understand the concepts of some imaginative play games, they may not be able to comprehend the dialogue within the play scenario they are embarking on. The role of the teacher is imperative here to investigate the capabilities and emergent capabilities of the children and to scaffold them. This scaffolding will encourage the inclusion (not just integration) of children with diverse needs on both an academic and a community level (Goransson & Nilholm, 2014; Olsen et al., 2019). The role of the teacher will be explored later in this chapter.

We advocate that at a classroom and practical level, teachers and educators who consider the rights of children to play andin play will provide a more inclusive classroom environment.

Factors affecting inclusivity

Social norms and power dynamics in play

In examining play through the lens of ableism (capabilities) often social inequalities develop unconsciously and most people have the privilege of benefiting from ableist systems that have evolved of and for the majority (Goodley, 2014). In the early childhood setting ‘friendship play’ is positioned as a possibility for everyone (Watson, 2018). Friendship and playing with friends are considered phenomena that naturally take place when children gather. It takes for granted the coming together of children so that play often develops unconsciously as a social opportunity for those who are able (have the capabilities) to participate without any barriers.

Young children actively draw on normalising discourses around their own and others’ identities and the homogenous group (Watson, 2018). They adjust their behaviours and observe the behaviour of others around them and can decide whether or not they might be the same (Watson, 2018). According to Watson, sanctioned discourses in the classroom contribute powerfully to the way children come to understand themselves. They also assist them in identifying differences in the classroom.

There are many power relations visible within children’s friendship play, this can sometimes go unnoticed, as friendship play is often uninterrupted and seen as ‘innocent’ (Grieshaber and McArdle, 2010). Power dynamics are often at play as children negotiate where they belong within a group. Leaders will emerge, some more able to take other children’s opinions and suggestions on board than others. Children make sense of the world through play and their competencies become visible as they engage in friendship play. Thus, children who are in the normative group are at an advantage and thus friendship play can work to conceal how children use play to position themselves more powerfully, often to the unconscious detriment of others (Watson, 2018).

The role of the educator is extremely important in friendship play to ensure that exclusionary practices do not go unnoticed (Weisberg et al., 2013). The notion of a teacher intervening is often at odds with the concept of children being able to navigate their own play. We totally acknowledge that there is a fine line here. We are not suggesting that teachers dominate friendship play, instead however monitor it to ensure that any unconscious exclusionary practices do not become the norm within the culture of a class.

Children may also need support to join a group and build those peer-to-peer friendships. Teachers can monitor and support those children to enable them to build these emerging competencies through role modelling, and by being their partner in play. When a child is partnered with a teacher, this is seen as a coveted position, and more of his/her peers may be interested in joining in their play then. This elevates the image of the child, builds social connections and enhances inclusivity in play (NCCA, 2009).

The social, emotional, and physical environments influence inclusivity within play

Inclusive classrooms have demonstrated positive learning outcomes for children, including high levels of academic performance, social skills, language competency, and a greater acceptance towards children with diverse needs (McDonnell & Hunt, 2014). However, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, typically developing children and more diverse learners have different needs that must be met (Watson, 2018). The social and physical environment of the play area have been highlighted as influential factors in catering for a more inclusive environment. It is important that although play areas are typically created with developing children in mind, consideration must be given to these aspects to promote inclusion within the classroom (Danniels & Pyle, 2022). The physical mobility and accessibility of all students is imperative. Access to all learning materials and areas within the room is a primary concern, from a physical aspect. However, if the social and emotional environment is not inclusive and meeting the needs of the children, accessibility is immaterial. This is evident in the example at the beginning of the chapter.

Thilde had access to the playground, but she did not engage in play within the playground environment. That is why it is so important to review the social and emotional aspects of the environment before the physical one. If the other elements are not there then inclusion may not exist at all.

Before creating a space for inclusive play to flourish, we must consider how we are going to first create a culture of participation that is crucial in the implementation of inclusive play (Casey, 2010). Practitioners of play can create vibrant playful environments that are visually stunning and encompass key learning centres for play to happen. However, we must always consider the needs of individual children in our settings.

Teachers’ skills, knowledge, attitude, and understanding of inclusive play environments

The landscape of classrooms has altered dramatically since the 1990’s, as discourses, policies and social attitudes changed and the inclusion of students with additional needs in education began. A number of key events accelerated these discourses: the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994) which encouraged governments to review how they respond to the diverse needs of students; the Education for All movement (UN, 2000) as it attempted to overcome inequalities within the educational systems, and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2006) as it recognised the rights of all children to be included and receive the individual support they may require throughout their education. These not only altered the landscape of the classroom but also the competencies, skills, and knowledge that teachers needed to ensure their diverse students progressed within their classes. The notion of inclusive play as a vehicle to achieve the necessary learning outcomes for their students became well documented (Grieshaber & McArdle, 2010).

The European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education specifies that teachers not only need to have the appropriate understanding, knowledge and skill set, but they also need to have certain values and attitudes to effectively work within inclusive settings (Borg et al., 2011). Also, the diverse range of students’ needs alter year on year. Thus, teacher training is still evolving to incorporate new skills and competencies that teachers need to succeed in the ever-changing diverse environment.

We posit that there are several elements that inclusive environments require to ensure they thrive. These include teachers who are willing to embrace collegiality and collaboration to enhance their knowledge and understanding of diverse learning abilities, nurture an inclusive school culture, and a willingness to reflect on and review our biases to ensure they are grounded in research.

Embrace collegiality and collaboration to enhance their knowledge and understanding of diverse learning abilities:

The word collaboration has its origin in “colabre or co-labor,” which refers to working together (Welch, 1998: 121). That notion of pooling resources together among professionals who have shared values and where a positive interdependence exists allows for inclusive learning environments (Snell, Janney and Elliot, 2005).

Nurture an inclusive school culture:

A school culture is a set of collective understandings (Carrington & Elkins, 2002), based on shared values (Noddings, 1992), with a common goal (Welch, 1998). A school culture that also embodies inclusivity ensures that biases are unpacked ethically (Palaiologou, 2014), diversity is celebrated (Kruse & Dedering, 2018), and collegiality and collaboration are inclusive and valued (Carrington & Elkins, 2002).

Why inclusion is so important

When inclusive strategies are not enforced the negative outcomes can be detrimental to all children. Therefore, inclusive strategies promote a positive self-image for all children and increase the self-efficacy for all children (Carrington & Elkins, 2002; Noddings, 1992). It creates a community that accepts and celebrates differences and ensures that developing and emergent capabilities are scaffolded (van Engelen et al., 2021). Noticing and acknowledging the signs of stress and anxiety in children is imperative to supporting them to accomplish a task they are concerned about. Children learn at an early age how to attract the attention of an adult. This tends to involve loud noises or gestures, signalling the need for support. However, stress and anxiety are not always visible through these gestures (French, 2018). Ensuring that children can self-express, and if they remain in control this does not hold less value or not get a response from teachers.

If Thilde, in our example at the beginning, had been expressing herself and her experience with abandonment through crying it would garner the attention of a teacher. This is a response that needs to be dealt with as it is challenging the normative play. However, in this scenario Thilde does not respond in that manner but she is in a position of stress and anxiety. However, it is not disturbing the normative play scenario and Thilde does not get any support to help her bridge the gap to socially participate within the play scenarios in the playground.

Thilde has no practice with these social norms, and she is not given any ‘training wheels’ or support to help her develop these capabilities.

Putting on the training wheels

For a more inclusive play environment to exist, and for children to step into the field of play confidently and competently, we argue that there might be an incentive to put on the ‘training wheels,’ and design didactical and pedagogical approaches towards play-competence. As the teacher creates a safe community (Lundy, 2007) and co-constructs a culture with the children, important relationships are formed (French, 2018; Hayes, 2007). This allows the teacher the perspective of resonating with the child and encouraging them to experience a connection with the world around them, by putting themselves into or stepping into the world around them (Pope, 2017). Those steps resonate with the field the person wishes to practice, transforming both the field as well as the person’s experience and skills in some way. These steps into play require engagement from the teacher who is teaching the child, but it also requires a spark, an engagement, a willingness to resonate with the rest of the playgroup from the child’s perspective (Baker, 2018). If the child sees no way into this culture or if they cannot mirror themselves even slightly within the activity at hand, the educator’s planning failed to create that spark.

Prior to the child putting on the training wheels there is a requirement that there is trust and safety between the child and the teacher. The experience, and reflection on the experience, is dependent on both the trust between the teacher and the child and also the trust the child has in his/her owns experience. Once this trusting collegial and honest community is established the continuity of this becomes central for inclusion to thrive and competency levels to increase.

Didactic and pedagogical strategies towards creating environments where inclusive play can thrive

Teacher Observation and Reflection as a vehicle to creating inclusive play environments

To create a collaborative and inclusive play environment we must first observe children at play. A distinctive feature of observations is the ability to obtain ‘live’ data on the spot, so teachers are not trying to remind themselves what had happened after the event occurred (Merriam & Grenier, 2019). The ability to observe and reflect on the observations is a skill all teachers need to acquire. Through observation teachers can create a holistic view of the child’s habits, social interactions, needs and capabilities, to inform a collaborative, collegial, transparent, dialogue between the whole team of teachers, outside agencies, parents, and the children themselves (Conn, 2014).

This skill allows teachers to pause and process their observations. Through reflection teachers can theorise and create strategies, environments, and play scenarios to support competencies recognised and scaffold emergent competencies (Moon, 2006).

This can only happen when teachers are frequently acting on their observations and amending the play environment in a meaningful way to suit the children. Creating a classroom environment that is fluid and changes to suit the needs of the child allows their voices and interests to be visible within their classroom. Applying these simple strategies of observation and reflection ensures our practice is informed by ‘live’ data that creates positive play scenarios for children and ensures their competencies are central to the environments they play in.

Accessing children’s voices to inform inclusivity within the classroom

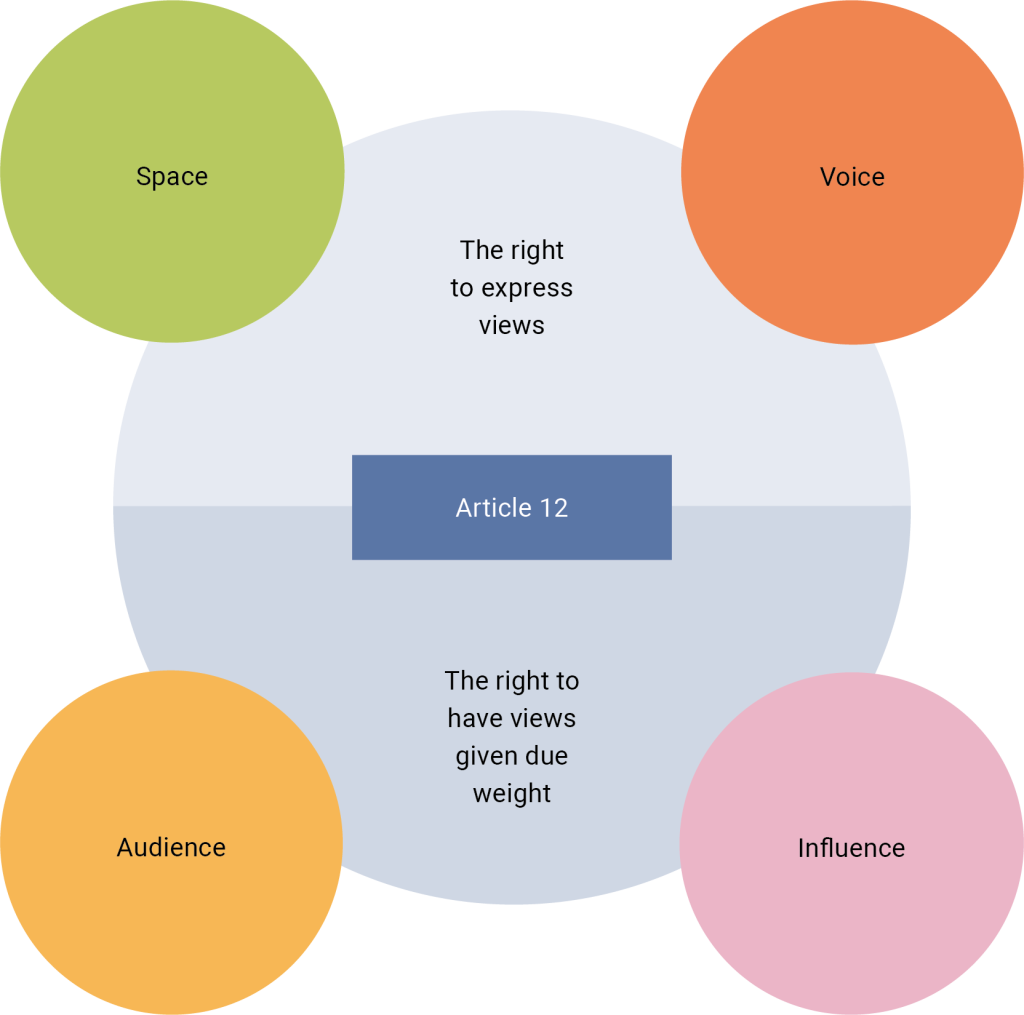

For the purposes of inclusive play, we propose that two participation models be used in conjunction with one another to improve inclusivity within the classroom: Lundy’s model of participation (Lundy, 2007) and Clark and Moss’s mosaic approach (2005).

Lundy’s (2007) model provides a way of conceptualising a child’s right to participation, as laid down in Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989). Lundy explores participation through four lenses that have a rational chronological order: space, voice, audience, and influence.

Figure 1: Lundy’s Model of Participation

Here she is proposing that teachers give children safe, inclusive opportunities to form and express their views and opinions. This ‘space’ allows their opinions to be formed. Children then must be facilitated to express these views. The children’s ‘voice’ needs to be heard. These opinions and views then need to be listened to. This is where the ‘audience’ (the teachers) listen to these views. Then, finally the views and opinions must influence change.

The ‘space’ is created to form opinions. Then the ‘voices’ of the children are accessed. The ‘audience’ listens with a view to allowing change in practice to occur. The opinions of the children ‘influence’ changes in practice (Lundy, 2007).

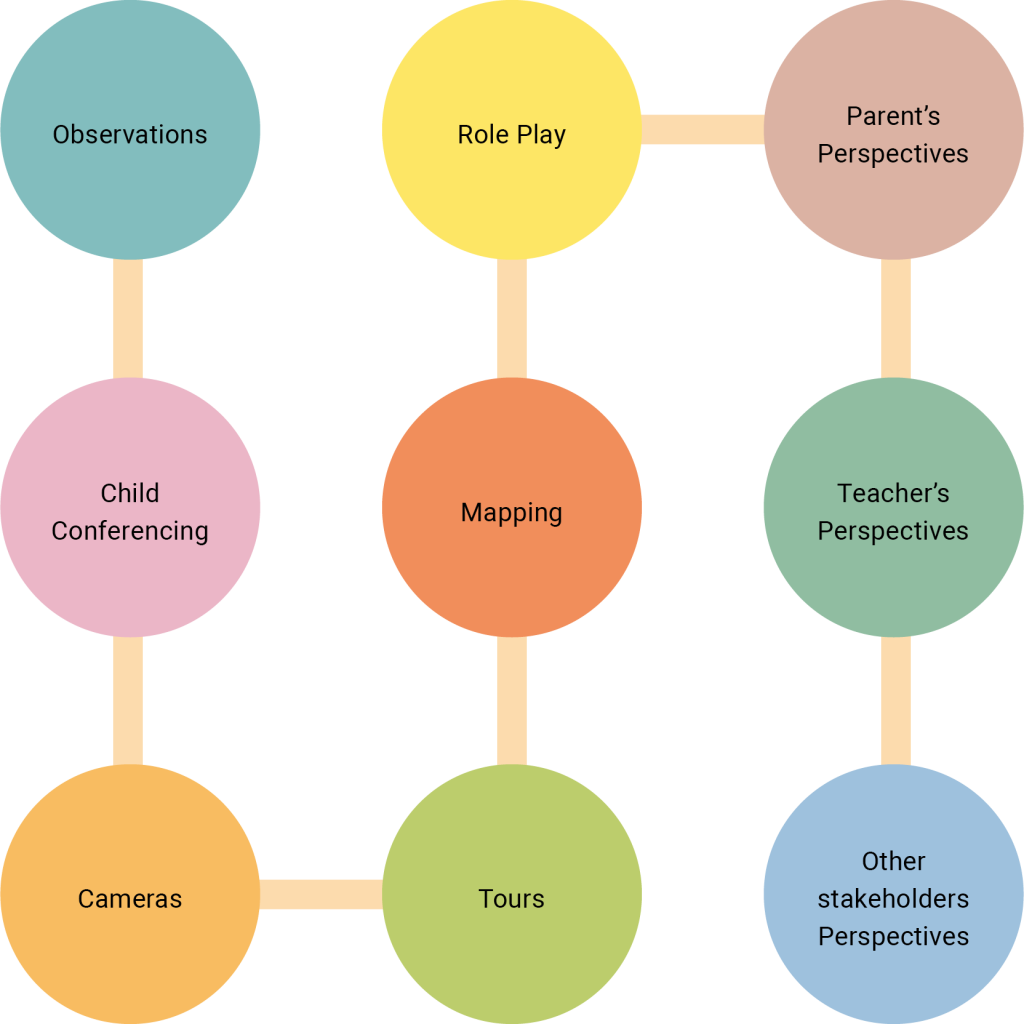

Clark and Moss’s (2005) mosaic approach fits nicely into Lundy’s (2007) accessing the voices of children section.

Figure 2: A depiction of Clark and Moss’s Mosaic Approach

Clark and Moss (2005) use multiple mediums to access children’s voices. We discussed earlier in their chapter about broadening the term ‘dialogue’ to include other forms of communication. This Mosaic approach fits directly into this concept.

Observations are used, as mentioned earlier in this chapter. Child conferencing is gathering a small number of children together to talk to them about a particular topic. There are some key points to note: a place that is familiar to the children will ensure they are relaxed, there are some strategies that can be used to ensure all voices are heard (the use of a puppet, ask each child a different question), and where possible record it so that it can be used as a reflection tool (Clark & Moss, 2005).

Using cameras as a tool to access children’s voices explores giving the children cameras and asking them to take photos of (whatever the topic you want to explore), for example, ‘What do you like playing with in the classroom?’ Then you can use the photos as a tool of reflection and dialogue with the children (Clark & Moss, 2005).

By creating role play scenarios for the children this allows them to act out real-life experiences. This encourages problem solving and higher order thinking and creates a safe space for children to give their opinions and feelings about a situation (Clark & Moss, 2005).

Tours and mapping both afford children the opportunity to express their thoughts and opinions through art and drawing. Children can go on a ‘tour’ of their room or their school or community and take pictures or draw areas that mean something to them. The children can create a ‘map’ of something using their drawings or photographs they took to express their opinion about an area in the room or how they feel in a space. Drawing can be considered as being in the same field of expression as play and speech (Bland, 2012). Children can learn to communicate through drawing, build a sense of trust, and develop fundamental skills for learning which help them feel included (Anning & Ring, 2004). This can be an important tool for those children who have limited or poor language skills as it is inviting and draws on the emotional side of a child’s wellbeing (Pope, 2017). Children can use drawings as a map through which to build on their own narratives of what is included in their drawings. In essence, it serves as a medium for emotion, where words, thoughts, and opinions can be expressed in a way other than words.

Clark and Moss (2005) also discuss reviewing parents, teachers, and other stakeholders’ perspectives. We discussed the importance of this open, honest, collegial, relationship earlier in this chapter and the relevance of the ‘funds of knowledge’ (Velez-Ibanes & Greenberg, 1992) that all parties can bring to ensure that a holistic image of the children is established.

We propose that the integration of these strategies into a classroom environment increases children’s rights, autonomy, and participation. It creates a framework for inclusive play and inclusive learning to exist.

Reflecting on our original example at the beginning of the chapter:

If these frameworks were explored with Thilde the teachers could gain valuable insights from Thilde about how she felt in the outdoor yard during play time. This information could inform their actions and would have afforded them the opportunity to support Thilde to have a more inclusive experience in the outside play spaces in the school. This would also support the teachers to highlight some of her capabilities and work on supporting her emergent capabilities.

Implementing the capabilities approach within a classroom

In our opinion, the capabilities approach can be used as a framework to support inclusion in play within the classroom. It is rights-based, holds the dignity of the child as a cornerstone and values difference.

Information gathering and relationship building:

To utilise the capabilities approach through a communicative framework within a classroom the starting point would be collaborative, transparent dialogues between the teacher and the parents/guardians. These reciprocally respectful conversations would be a vehicle to share relevant information for the good of the child. This becomes the foundation of a meaningful relationship, where the rights and dignity of the child are at the centre. Then the teacher would use a multimodal technique to gather information about the capabilities and needs of the child, with the child. This can be done through the use of the mosaic approach (Clark & Moss, 2005) and Lundy’s model of participation (2007). Collaboration with other professionals and colleagues would further enhance the knowledge base and ensure a holistic view of the child was used to inform inclusive strategies.

Capabilities of the child:

When the information is gathered, a holistic picture of the child is visible to the teachers. A child’s developing capabilities can be used to support inclusion into peer groups and meaningful play.

Supports to be put in place:

Support systems to ensure capabilities are utilised and can be put in place.

Reflect and review:

Remembering that this is a snapshot in time and these capabilities may be developing capabilities and may alter over time. New supports will be necessary as the supports in place work.

The role of the teacher

The importance of questioning the ‘norm’

Within this chapter we have used the word ‘normative’ frequently. We discussed normative playing fields, and normative culture. We looked at inclusive play through a ‘normative’ lens to unpack what this looks like for more diverse learners. We argue that a major role of the teacher is to question ‘normative’ ways of doing, thinking and being. We argue that by questioning the ‘norm’ teachers are saying they are willing to change and alter their practices. Reviewing Lundy’s model (2007) suggests the audience needs to want change to occur for the child’s ‘voice’ to ‘influence’ their learning environment. Therefore, an important role of the teacher is to question ‘normative’ practices and advocate for change. We posit that the ability to constantly alter our environment, practices, and approaches to suit the needs of our ever-changing diverse students is paramount to the composition of a good teacher.

When we reflect on our example at the beginning of the chapter, we saw Thilde putting her faith in the teacher’s ability to alter ‘normative’ practice. We saw the negative impact it had on Thilde when the teacher did not do this. Thilde was creating her own ‘space’, for her ‘voice’ to be heard, then Thilde’s ‘audience’ did not listen and therefore her voice did not ‘influence’ change. This meant that Thilde’s experience in the yard was not one of inclusion and the teachers missed an opportunity to support inclusive play.

Another important point is that for Thilde, in this example, to find help required that she had the capability of even asking for help when expressing her position of stress. Thilde found a way to voice her concern, in part through another, possiblymore communicative child, but her concerns were not met directly. Thilde was expressing that her developing or emerging capabilities were not strong enough yet and she needed help to step into this ‘normative’ playground. Had the Lundy model and the mosaic approach been used here in conjunction with the capabilities approach then these developing capabilities would have been acknowledged, and strategies could have been put in place.

Finally, this throws up another nuance that we discussed at length within this chapter. Teachers’ attitude to play and what their role is within play. We discussed the difference between children’s rights to play and children’s rights in play and how the role of the teacher becomes one of observer, facilitator, and sometimes a participant of play with the children to ensure that children’s rights in play are met.

In the example at the beginning of this chapter the teachers stood separately in a particular spot in the yard. They did not engage in play with the children and did not step in to support play with the children. It would be fair to assume that their view of their role was within a supervisory capacity. The children’s rights in play were not reviewed nor did they appear to be a concern for them. Therefore, we argue that for teachers to support children’s rights in play they need to review their position and impact on play. The value of play should be paramount for teachers to ensure they support these rights for children.

Had the teacher’s questioned this ‘normative’ role within the playground then the lack of inclusive play could have been addressed and Thilde’s experience in the yard may have altered dramatically. Play as a position to explore the normative, to challenge what the child already knows and to push boundaries, values, and practice as an attempt to work into and reproduce the normative is an important part of the role of a teacher. Sommer et al (2020) argue that the kind of pedagogy that favours guiding children’s imaginative play and negotiating while playing, in kindergarten helps them to step into the school system, and in this chapter the argument is, that this kind of play encourages the children to practice social skills. This also supports children within primary school to include each other and gain access to a broader collection of social capabilities (Sommer et al., 2020).

The reconceptualisation of the role of the teacher

As teachers we have an innate desire to help children learn. To learn through exploration, reflection and presenting broad horizons. To learn math, languages, and science; why the world is the way it is, to learn about morals and ethics. However, for children to learn there needs to be a trusting and collegial relationship between them and the teachers in their class.

Therefore, we posit that we as teachers implement the strategies put forward in this chapter to encompass inclusive play into our practice and to reinforce play as both a formal and informal learning possibility acknowledging the capabilities, and developing capabilities, of each child.

We believe the conceptualisation of the role of the teacher should be viewed through four lenses:

- The lens of an entrepreneur. The entrepreneur is constantly questioning the ‘norm’ by consistently creating and recreating new ideas, practices, and methods of doing things.

- The lens of a detective, constantly observing and working out the children’s capabilities and competencies. A detective who questions the experiences of every child in every play scenario, accessing their voices and identifies clues to highlight participation, inclusion whilst recognising marginalisation and exclusion.

- The lens of a coach who values the structure and elements of inclusive play. A coach who is willing to participate in play, to ensure that children’s rights to play and in play are met. A coach who encourages relationships between social skills and play skills, in a safe and trusting environment to elevate all children’s capabilities to encourage participation in all activities.

- The lens of an active participant. Looking at a classroom as an active participant instead of a facilitator allows you to see the classroom as the children see it. By being an active participant, it allows you to co-construct a play culture, participate in play scenarios, and therefore co-create the values of inclusive play within the classroom. Active participants can encourage all voices to be heard, to be valued and to influence change.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

Reviewing the example at the beginning of the chapter. How do you think you would answer the following questions?

- By implementing the capabilities approach in our example above with Thilde heading out to the classroom what would you have done differently?

- What do you think her capabilities were?

- What supports do you think she needed to scaffold her integration into play in the yard?

Reviewing your practice and pedagogy:

- What methods would you use to access your students’ voices through the mosaic approach?

- How would you implement Lundy’s model of participation within your classroom?

- How would you ascertain your students’ capabilities?

Creating a collegial and inclusive culture in the classroom:

- What is your view of inclusive play?

- How do you value inclusive play?

- What ‘normative’ behaviour could you question within your school?

- How could you bring other teachers on this journey with you?

Inclusive play and your part in it:

- What is your understanding of inclusive play?

- How can you participate in play to ensure your student’s rights to play and their rights in play are met?