Section 6: Building Inclusive School Cultures and Policies

Inclusive School Culture

Angele Deguara; Jessica Lament; Thomas Joseph O Shaughnessy; and Leah O'Toole

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Don’t judge a book by its cover

ORGANISING A HUMAN LIBRARY TO FOSTER A CHANGE IN ATTITUDES TOWARDS DIVERSITY IN SCHOOLS

“The town in which Westfield primary school is located has experienced a changing demographic in recent years due to increased global migration. Across the country and indeed across Europe, the rise of right wing politics has led to increasing incidents of discrimination, and Westfield has not been immune to this trend. Following some disturbing incidents of bullying based on gender, class, disability and ethnicity, the staff team of the school decided that something proactive needed to be done to address the changing school climate, rather than simply responding to incidents as they arose. After conducting research on various approaches to developing an inclusive school culture, they decided to organise a Human Library (see below for details on how to organise one yourself!). In the Westfield Human Library, members of the school community had the opportunity to meet people who they normally do not have access to. These included refugees, persons with disabilities, ex-prisoners, ex-drug users, victims of domestic violence, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, people who have gender atypical jobs, people of different skin colour, parents representing different family structures such as same sex or lone parents and people from religious and ethnic minorities. The human books available in the library were chosen depending on the school context and the demographics of the school population, especially the students. Similarly, the conversations, use of language, the stories told depended on the demographics of the readers. The Human Library was a safe space where members of the school community were able to ask difficult questions and to be provided with honest answers about different realities and human experiences. Readers of these human books learned not to judge books by their cover; that there is a human being inside every cover; they learned to reflect upon their prejudices and attitudes towards the social categories represented by each book. Visitors to the Human Library who came themselves from a minority, disadvantaged or stigmatised background appreciated being represented by human books with whom they could identify, from whom they could learn about challenges and how they may be overcome. The aim of the human library was to challenge attitudes, assumptions and taken-for-granted stereotypes about a social category of people. While it didn’t solve every problem of society, the feedback to the principal from the school community of Westfield was very positive, and teachers noted a reduction in incidents of bullying afterwards. In reflecting on the activity afterwards, the general consensus of staff, children and families was that the Human Library was a hugely successful and effective way to allow people to reflect on their attitudes towards diversity and work to create a school culture where everyone feels welcome, safe and represented.”

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is an inclusive school culture?

- Why is an inclusive school culture important?

- How is an inclusive school culture implemented?

Introduction to Topic

What is an inclusive school culture?

Nowadays societies are increasingly socially and culturally diverse, and school communities are often a reflection of this diversity (Killen & Rutland, 2022; Mallia Borg, 2007). Social exclusion, discrimination, bullying, and expressions of hate are also widespread (Killen & Rutland 2022). Therefore, the need to create an inclusive school environment and to address prejudice and discrimination has become more urgent. Building and fostering an inclusive school culture within the school community in order to respond to these trends has been recognised by the international educational community and by local learning communities and educational leaders as well as by policy makers who legislate in favour of inclusivity, diversity and equality. The foreword to A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education (UNESCO, 2017) refers to the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and to Sustainable Development Goal 4 whose aim is inclusive and equitable quality education for all. The goal is for educational institutions and learning environments to be sensitive to the needs of all learners, to be inclusive, safe, non-violent, child-friendly, gender-sensitive and to cater for all abilities.

Inclusion policies have become more common within educational systems and are increasingly becoming incorporated within teacher education curricula in different countries, as educational institutions and educators are expected to be skilled in ‘inclusion’ even if there is no universally accepted definition of inclusion, or how best it can be promoted and implemented (Essex, Alexiadou & Zwozdiak-Myers, 2021). Consequently, student teachers may have to deal with different approaches to inclusion and diversity which may at times also be conflicting or contradictory (Essex, Alexiadou & Zwozdiak-Myers, 2021).

Within the social sciences, there is also no universally accepted definition of culture. It may be considered a contested concept since different scholars have provided different definitions and approaches to defining the concept (Spencer-Oatey, 2012). Jahoda (2012) claims that culture is difficult to define as it is a social construct created from a wide range of complex phenomena. However, others are more explicit in terms of phenomena and state that culture flows from standards, values, beliefs, habits, and practices developed gradually over a period of time (Peterson & Deal, 1998).

On the basis of Spencer-Oatey’s (2012) discussion on the various attempts at defining culture, we may broadly define culture as a set of norms and values, attitudes, beliefs, rituals, ways of doing things, assumptions and expectations that are shared by a social group. Culture is learned from one’s social environment through the various agents of socialisation such as the family, the school, religion, peer groups and so on. Similarly, defining a school culture is not straightforward but it has been described (Deal & Peterson, 2016) as having a powerful effect on school life. According to the authors, it is something which is not easy to pinpoint but rather affects how things are done at school, how people interact, norms, forms of dress, and various other elements within an educational institution. Therefore, we may define it as the set of norms, informal rules, values, rituals, traditions, goals and practices that is developed, shared, promoted, learned and reproduced within an educational setting and learning community but which, at the same time, remains slightly “elusive” and hidden, as Deal and Peterson (2016, p. 7) describe it. Cultures include both material and non-material elements, that is those aspects of a culture which are tangible or visible and those aspects which are abstract such as values and attitudes (Hahn, 2018).

For a school culture to be inclusive, it needs to create an atmosphere which is embracing of diversity and which ensures that every member of the school community is treated with respect and dignity and embraced as a unique person regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, religion, belief, sexual orientation, parental or family status, geographic origin, political views, socioeconomic background, age and ability. Material aspects of an inclusive school culture would include physical structures such as accessible buildings, universal bathrooms, religious symbols representing different belief systems, teaching resources and materials such as images representing diversity or dolls of different skin colour and body shape used with early learners. Non-material aspects would include non-tangible elements such as the values, norms, philosophies, beliefs and attitudes which are often the drivers behind the realisation of such a culture. Values of social justice, equality and inclusion, feelings of belonging, ideas about schools being safe spaces for all, an appreciation of diversity in all its forms are all examples of non-material elements of inclusive culture.

An inclusive school also strives to go beyond the idea and practice of integration, where, for example, students with disabilities learn alongside students without disabilities. An inclusive school is not only concerned with social categories that are more likely to be stigmatised or marginalised such as gender non-conformers, persons with disabilities or those coming from minority ethnic groups, but emphasises the inclusion of all members of the school community. It strives to put into practice the concepts of universality and equality in education and considers diversity, regardless of how it is manifested, as a positive source of enrichment, within a broader scheme based on the value of social justice (Moliner Miravet & Moliner García, 2013). Inclusive schools embrace and celebrate diversity to ensure that all students have the same rights and opportunities to fulfil their potential in all areas (Hannigan, Grima-Farrell & Wardman, 2019; Villa & Thousand, 2005).

An inclusive school culture aims to foster a sense of community and belonging within the educational community (Osterman, 2000) and to ensure that all members of the community consider their school as a safe space where they can be themselves, and where they can flourish academically and find care and support. For a school culture to be really inclusive, it needs to be shared by the whole school community, as its values and principles guide everyday interaction, decisions, policies and attitudes, both on a macro and micro level within an educational institution and learning community.

An inclusive school culture is not static. In order to adequately respond to changing trends in social and cultural diversity, inclusive school cultures are developed, reproduced and reconstructed through everyday interaction, activities, initiatives, reflection, decisions, procedures, objectives of the institutions and the communities within them. It becomes an essential element of the institution in the sense that it underlies the whole structure and day to day operations and is reflected throughout, both in its formal and informal practices (Moliner Miravet & Moliner García, 2013). In other words, it is a way of thinking.

Why is an inclusive school culture important?

Educational institutions, educational leaders and educators play a crucial role in the creation of inclusive learning spaces. When schools take proactive action to bring about change, they are more likely to succeed in reducing social and cultural exclusion as well as bias and discrimination and to create and maintain a safe and inclusive environment for all. An inclusive school culture creates a more conducive learning environment, even if it does not necessarily guarantee academic success. These include students who; do not feel accepted or who lack friends, experience rejection, discrimination or bullying, are less likely to engage or perform well academically, who lack motivation, whose attendance is poor or are likely to drop out of school, and their social development suffers (Juvonen et al., 2019; Killen & Rutland, 2022).

In recent decades, the educational community has become more sensitised to the varying needs of students. While all students have needs, some students may have more needs and may require more support and attention. Mallia Borg (2007) notes a paradigm shift in education where instead of perceiving students as failures, the onus is placed on the educational system for failing to cater for their needs. In literature, considerable attention has been given to the benefits of including learners with special needs. However, research shows that the benefits of inclusivity extend beyond students with special needs. Utomo and Thaibah (2021) describes how inclusive education is particularly beneficial for character building among all students, as experiences of inclusionary practices teach life skills and promote positive attitudes towards others who have different needs. An inclusive school culture also encourages students to take the side of those who are willing to offer support and assistance to those who need it (Killen & Rutland, 2022).

A review of initiatives in various countries, aimed at promoting an inclusive educational environment particularly for transgender young people (Domínguez-Martínez & Robles, 2019), suggests that educational institutions which have in place policies protecting gender minorities are beneficial in a number of ways. Educational spaces where binary notions of gender are challenged, where students can express their gender without fearing the consequences and which embrace diversity, tend to create a more positive and safe school climate, enhance overall wellbeing, decrease instances of victimisation and harassment and reduce absenteeism. A positive practice implemented in several countries is the formation of gay-straight alliances, which has proved to have a number of positive effects, particularly for young transgender people. School curricula which are representative of minorities also tend to have a positive impact on enhancing wellbeing and reducing victimisation and harassment of students who are considered different (Domínguez-Martínez & Robles, 2019).

A qualitative study conducted with five school principals who adopted an inclusive approach in their schools found that inclusive cultures, based on a philosophy of inclusion as “a way of thinking and acting”, ensures that all members of the community become meaningfully involved and gain equally from it (Osiname, 2018). An inclusive school culture strives to eliminate social exclusion and barriers that hinder students from enjoying their rights and from feeling valued, respected, protected, and safe. This, in turn, motivates members of the school community to express themselves freely, openly, and honestly, knowing that they will be listened to and have their views respected. Staff and students have the opportunity to approach the principal and express their feelings and concerns without the fear of being punished or chastised. Adopting an open-door policy can be an effective way of encouraging openness as it conveys a message that everyone can contribute to building an inclusive school environment (Osiname, 2018).

The rapid advances and dependence on technology since the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of digital inclusion and investment in digital technology. Research by Kim, Yi & Hong (2021) describes the inequalities of access to digital technology at home or school and noted that disparities were greater when other factors such as socio-economic background are taken into account. School cultures should be digitally inclusive as unequal access to digital technology is likely to have long term implications.

Inclusive school cultures are important as they respond to students’ need for belonging (Osterman, 2000). In a context where mental health concerns are becoming increasingly critical, inclusive school cultures may prove vital for enhancing psychological well-being, and for highlighting how exclusion, disengagement from school, education-related stress, marginalisation, lack of friends or popularity may all have a significant detrimental impact on the mental health of students (Hannigan, Grima-Farrell & Wardman, 2019).

How is an inclusive school culture implemented?

Diversity within a school setting does not automatically ensure inclusion. Inclusion is a goal that needs to be developed and promoted proactively (Juvonen, 2019). The Council of the European Union reiterates the importance of implementing inclusivity in schools in its 2018 Recommendation on promoting common values, inclusive education, and the European dimension of teaching:

“Ensuring effective equal access to quality inclusive education for all learners, including those of migrant origins, those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, those with special needs and those with disabilities — in line with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities — is indispensable for achieving more cohesive societies” (Council of the European Union, 2018, point no. 16).

Responding to social and cultural diversity in our educational systems is no easy task. It is a challenge that many schools, colleges and universities are now implementing. Educational institutions striving to foster a culture of inclusion often need to implement radical changes which require commitment and hard work involving both deconstruction and reconstruction. Fostering a culture of inclusion often requires the dismantling of all that hinders its development such as attitudes towards diversity and may necessitate the transformation of the whole educational institution. It also requires the motivation of the whole school community in order to ensure the contribution of all involved (Moliner Miravet & Moliner García, 2013).

In his foreword to A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education, Dr Qian Tang (Unesco, 2017) writes that:

“To achieve this ambitious goal, countries should ensure inclusion and equity in and through education systems and programs. This includes taking steps to prevent and address all forms of exclusion and marginalisation, disparity, vulnerability and inequality in educational access, participation, and completion as well as in learning processes and outcomes. It also requires understanding learners’ diversities as opportunities in order to enhance and democratise learning for all students” (Foreword).

Research by Fine-Davis & Faas (2014) into how schools in six European countries address cultural diversity revealed that European societies approach diversity in education based on different models. In countries such as Germany, Greece and Ireland, the concepts of interculturalism and intercultural education were preferred while in Britain, the Netherlands, Canada, the United States and Malaysia, the term multiculturalism is used. The authors also cite research which shows that national historical and political legacies as well as the topics taught also influenced educational policies and practices in different European countries (Fine-Davis & Faas, 2014).

The authors of this chapter have identified four major components that play a crucial role in the implementation of an inclusive school culture. These include attitudes, collaboration, knowledge, and leadership.

Attitudes – A multi-layered approach aims to bring about attitudinal and behavioural changes among students as well as administrators, educators, and other members of the school community (Juvonen et al., 2019; Killen & Rutland 2022; Mallia Borg, 2007; Moliner Miravet & Moliner García, 2013).

Collaboration – Different stakeholders, entities and communities working together, supporting and learning from each other. It involves educators working together, facilitating a leadership and educational authority structure and a supportive legal framework, involving parents and students, collaborating with other school communities, and sharing a determination to reach common goals (Lave and Wenger, 1998).

Knowledge – Knowledge, more specifically research-based evidence, that guides the realisation of school inclusion in terms of different beliefs, needs and cultures, family situations and socio-economic backgrounds of everyone in the school community. Acknowledging the importance of knowledge and recognising different sources of knowledge, e.g., through interaction with students and their parents, the provision of training or learning from the good or bad practices of other schools (Razer, Friedman & Warshofsky, 2013).

Leadership – The role of educators and administrators as role models whose behaviour may be reflected in the attitudes and behaviour of their students (Juvonen, 2019) and the whole school community. Educational leaders may take on the roles of facilitators, innovators, visionaries and strategists, as well as enablers of an inclusive school culture and must be open to change.

All of these above combine to create ‘safe spaces’ in educational settings where all staff, students, and members of the wider educational community feel welcome, respected, safe and visible.

Key aspects

Attitudes

Attitudes refer to how societies, communities and individuals learn to perceive issues, people, things, objects, and events in a particular way which could be positive or negative but which could also be ambivalent at times (Cherry, 2024). According to the same author, psychologists tend to consider attitudes as having three components. These include; an affective component referring to how one may feel about a social group of people such as Muslim students; a cognitive component relating to the beliefs and ideas that one may have about an issue such as the inclusion of trans students; and a behavioural dimension where attitudes about someone or something may influence how people act, even in an unconscious manner, such as addressing the assistant of a learner with disability rather than the learner.

Moliner Miravet and Moliner García (2013) consider two factors as being crucial for the promotion of a culture of inclusion: “(a) a set of objectives agreed on by the educational community, and (b) shared values” (p. 1376). They identify a number of factors as contributing to the achievement of consensus among the teaching community such as the degree of teaching experience, the position one occupies within the school as well as the gender of the educator and the subject one teaches. Although there are convergent views about the issue of how to establish “a common language” throughout an institution, they argue that a shared culture of inclusivity reinforces the sense of community and belonging within an educational setting (Moliner Miravet & Moliner García 2013). The question remains on how to achieve this.

How does a school community come to embrace a common set of objectives and values? This is a long-term goal which can only be achieved through a passionate, committed, joint and continuous effort and involves challenging taken for granted assumptions, transgressing boundaries, orthodox views and methods. Attitudes are shaped through socialisation and learning at home and at school, through media influence, social experiences, and observation, and while they may become ingrained, it does not mean that they are incapable of change (Cherry, 2024).

The Recommendation on promoting common values, inclusive education, and the European dimension of teaching (Council of the European Union, 2018) suggests that educational staff should be able “ to promote common values and deliver inclusive education, through:

- measures to empower educational staff helping them convey common values, and promote active citizenship while transmitting a sense of belonging and responding to the diverse needs of learners; and

- promoting initial and continued education, exchanges and peer learning and peer counselling activities as well as guidance and mentoring for educational staff”.

Heads of school play an important role here as they are often the drivers behind a change in attitudes. Acting as both role models and facilitators, heads of schools who facilitate openness, accessibility, critical feedback, democratic participation and involve all members of the school community are more likely to bring about an attitude change towards inclusion (Osiname, 2018). Embarking on a project which strives to bring about a change in attitudes towards diversity within a school setting may necessitate both direct and indirect interventions as well as strategies targeting different processes and practices. These include; developing an inclusion policy and multicultural curriculum as well as indirect ways through which messages about inclusion, acceptance, equality and social justice are conveyed, e.g., through the use of images in class or, if working with small children, through the use of dolls, soft toys or puppets having different body shapes or skin colour and hair textures (Juvonen et al., 2019). The hidden curriculum is a primary tool through which inclusivity may become a way of thinking within an educational institution.

Changing attitudes towards diversity could be encouraged by facilitating communication among members of diverse groups. This helps to reduce negative stereotypes and biases about those who are different. Within their classrooms, teachers may find ways of encouraging inter-group interaction, e.g., through seating arrangements or group work. Interaction across groups may also be encouraged through extracurricular activities or themed clubs which attract students from different backgrounds. It may also be encouraged through a peer mentoring system (Juvonen, 2019, Killen & Rutland, 2022). Creating a school and classroom context where students interact with those who are different from themselves is an excellent opportunity to promote openness to diversity. Intergroup interaction enables young people to see both the differences and the similarities that exist between them and their peers, and to appreciate differences as alternative realities rather than as threats (Bayram, Özdemir & Boersma, 2021).

Research suggests that how educators respond to diversity in schools and in their classrooms is of utmost importance since their attitudes are reflected in their classroom practices and will have an effect on student social wellbeing and educational performance (Wang et al., 2022). Garmon (2004) suggested six factors that seem to carry central significance in bringing about effective transformation in the attitudes of teachers towards diversity. These factors include openness, self-awareness/self-reflection and commitment in terms of disposition and intercultural, educational, and support group experiences. As societies and classrooms continuously change and become more diverse, teachers need to be equipped with the necessary skills, knowledge and attitudes to address these realities in an effective way. They need constant training and preparation to address the needs of all learners and to promote inclusivity in their everyday practices and interactions with students and colleagues (Fine-Davis & Faas, 2014; Mallia Borg, 2007). The importance of revisiting teacher education has also been recognised. In light changing demographics of our education systems, many Europeans countries are reforming teacher education policies to ensure that teachers will be equipped to face the challenges of inclusive education (Florian & Camedda, 2020)

Initiatives aimed at attitudinal changes towards diversity strive to eliminate biases, negative stereotypes and other exclusionary practices that have negative consequences on both victims and perpetrators. During the transition from childhood to adolescence, students become increasingly aware of social inequalities and of the possible links between social stereotypes and of being unjustly treated by peers or other members of the school community (Killen & Rutland, 2022). Adolescence is an age where youngsters are trying to better understand the world around them and to form opinions and attitudes about it. Research suggests that as they become more independent of their parents, they tend to be more open to ideas about diversity and that schools have an important role to play in fostering positive attitudes about diversity (Bayram, Özdemir & Boersma, 2021). At such a sensitive stage in their development, school experiences can have a significant impact on attitudes of adolescents towards classmates, according to Eckstein, Miklikowska & Noack (2021). They also note that school climates which promote democratic participation and supportive attitudes towards classmates tend to minimise prejudice among young adolescents. The authors also suggest that schools should take into consideration differences in students and across the school context. For example, student age when implementing initiatives which may facilitate the development of positive intergroup attitudes (Eckstein, Miklikowska & Noack, 2021).

Students in preschool and primary school are actively developing their attitudes and understanding about their culture and society. They learn from both their own direct experiences as well as from their exposure to their environment, media, and other people around them. Additionally, experiences that young students have in their primary social groups, like school, have a great impact on their attitudes (Triandis, Adamopoulos & Brinberg, 1984).

For example, a range of research has shown that gender stereotyping becomes embedded in young children’s experiences in education and in life more generally from their earliest days. This video shows examples of how adults subtly and not-so-subtly direct children’s attention towards gender stereotyped toys, often unconsciously: Girl toys vs boy toys: The experiment – BBC Stories – YouTube. Children may internalise these messages about what is ‘right’ for them based on their gender, and so begin to choose gender stereotyped activities, perpetuating behaviours and limiting their opportunities for learning, development and play. For example, Coyne’s research has explored how exposure to stereotyped super-hero content (Coyne et al., 2014) or Disney Princess content (Coyne et al., 2016) influences children’s play and gender stereotypical behaviour. Perhaps even more worrying is evidence that children’s attitudes towards children who play in gender atypical ways (as traditionally defined) tend to be negative, and children may police each other’s gender conforming behaviour, even to the extent of bullying (O’Toole and Hayes, 2020). Kuvlanka and colleagues (2014) also showed that gender non-conforming and trans children can be at risk of difficult peer interactions. This emphasises the importance of educators reflecting on their practice to ensure that they are not consciously or unconsciously communicating discriminatory messages to children. Practice that helps to counter such narratives in education includes ensuring to offer equal experiences to students regardless of gender, choosing resources mindfully (for example books in which characters challenge gender stereotypes) and ensuring opportunities for all genders to mix together so that stereotypes can be challenged through direct experience (see → Sex/Gender Education chapter of this book).

These examples apply to multiple dimensions of diversity. Studies have found, for example, that direct contact experiences with students with disabilities in primary school positively influenced non disabled students’ attitudes about inclusion (Allport, 1954; Diamond et al., 1997; Okagkai et al., 1998; Pettigrew, 1998). Students who had contact with a peer with a disability or had a family member with a disability had more positive attitudes towards students with disabilities compared to students who were simply attending an inclusive class who did not have any direct contact with peers with disabilities or had a family member with a disability (Goncalves, 2014; Schwab, 2017). The Human Library approach described in the example case is one strategy to support this.

A Human Library may be simply described as a library where instead of books, there are people who are willing to share their stories with readers. These human books are volunteers and would typically represent social categories of people that tend to be the target of stigma, discrimination, prejudice, hate, bullying and marginalisation due to factors including colour of skin, religion, body shape, disability, gender nonconformity, sexual orientation, health status, beliefs and so on. The aim of a human library is to challenge stereotypical ideas, attitudes, feelings and beliefs about these social groups through contact and dialogue.

Visitors to a Human Library, such as members of the school community, teachers, students and parents should be informed beforehand of the significance and scope of the activity. Apart from the practical dimensions of this, the school has the opportunity to put the organisation of the library within its broader agenda of promoting positive attitudes towards diversity as part of a holistic, inclusive school culture.

‘Books’ sit around small tables or on an armchair where visitors can join to listen to the stories. Some ‘books’ might also sit on carpets and visitors could sit in front of them on cushions on the floor. Each book should have a sign, representing the book title indicating the social category that is being represented. At the entrance to the library, there could be a colourful visual displayed with the list of books available on the day.

Example of Human Library with children and teenagers: Kids Meet A Deaf Person | HiHo Kids – YouTube

Evidence exists of the effectiveness of such approaches to contact and dialogue for reducing stigma and prejudice. For example, early exposure to information about peers with disabilities can increase children’s acceptance of peers with varying abilities (Okagaki et al., 1998). Loeber and colleagues (2022) also found that “learning new information about peers with non-compliant classroom behaviour by students can correct their negative views and existing misconceptions and ultimately lead to positive attitudes” (Loeber et al., 2022, p. 4). These findings were reflected in a study by Ostrosky et al., (2013) where preschool students spent time reading and discussing books with characters with disabilities in their classroom as well as at home with their families. The study found that preschool students had an increase in their positive attitude from the combined effect of contact with peers with disabilities and from information shared through books (Ostrosky et al., 2013).

This type of intervention on inclusion can be extrapolated to other dimensions of diversity and is likely to result in desired outcomes such as developing positive attitudes towards inclusion. As young students are exposed through direct contact experiences in addition to literature and multimedia, they are also developing their sense of the world and their understanding of how things work together.

Challenges to attitude change

The benefits of having a shared set of values and attitudes which are positive and open to inclusion are widely recognised. Yet, bringing about an attitude change is not an easy task. Despite the importance of implementing, and sustaining, an inclusive school culture, schools face a number of challenges. While School leadership and the teaching staff are major drivers of change, some may not be open to change or be unwilling to embrace inclusion themselves, or act as role models in the process. Existing literature highlights where teachers may be less receptive to the idea of inclusive education (Revelian Steven & Tibategeza Eustard, 2022). School leaders, or any agents of change within the school, are likely to face resistance (Zimmerman, 2006) and lack of resources or legal frameworks may also pose difficulties. Teachers may resist change for various reasons such as an unwillingness to change their habits, or because they lack the knowledge and resources or necessary skills to implement change (Yılmaz & Kılıçoğlu, 2013). Changing cultural attitudes is demanding in any context. Nevertheless, it is a key driver to facilitating change and in light of the social and cultural realities of our schools.

Collaboration

Inclusive school culture can be supported and developed through a collaborative approach with school staff, children, families and the wider school community. Collaboration in schools is rooted in, and depends on, the relationships that are made up from repeated interactions across time (Pianta et al., 2003). It could be argued that relationships underpin all learning, and that a focus on creating positive relationships (or in German ‘Beziehungsarbeit’) is a crucial element of an inclusive school (see → Relationships chapter of this book). In terms of collaboration, each participant in an inclusive school brings different orientations, knowledge, expectations, priorities, and interests (Foong et al., 2018). In the context of supportive relationships, such diversity can be leveraged so that these become more than the sum of their parts, but within hostile, defensive or disrespectful relationships these differences can become a source of tension. Recognising this and working towards the creation of inclusive school collaboration, does not suggest that we all have to agree with each other or be homogenous in our thinking. In fact the opposite may be true: for example in an inclusive setting the needs and wishes of individual parents may not always align with the needs and wishes of the community as a whole or of individuals within the school. However, the negotiation, rather than avoidance, of these tensions is part of a democratic society (O’Toole, Dowling & McElheron, 2023) and an inclusive school climate allows for them to be deconstructed in respectful ways. This is just one of many ways in which relationships impact on the inclusivity of a school culture. Some examples of collaborative approaches for the establishment of inclusive school cultures include communities of practice and co-teaching.

Communities of Practice

A Community of Practice (CoP) is just one way to support and foster collaboration within a school environment. A CoP consists of a network of people who frequently come together to share, learn, and work to achieve agreed targets or goals. A CoP is important as it also allows educators and other educational professionals to assemble and share insights from their previous experiences (Ostrowski et al., 2017). The development of a CoP can be a complex undertaking as it tends to have a multitude of moving parts and requires buy-in and time investment from other stakeholders. From a leadership perspective, CoP provide a safe space for school leaders to learn, gain new perspectives, test new ideas and engage in meaningful, authentic feedback and reflection (Bickmore et al., 2021). This type of safe space can foster deep conversations and build educator confidence (Patton & Parker, 2017).

CoP can also play a monument role in igniting and driving teacher professional development (Schlager & Fusco, 2003). Evidence has shown that the adoption of a teacher CoP can result in more positive views of teacher professional development and enhanced leadership behaviours (Bickmore et al., 2021). Moreover, for some teachers, a CoP provides teachers with the opportunity to engage in dialogue with others on topics including research, teaching practice, and student learning (Patton & Parker, 2017). As a CoP gradually matures, it may also begin to produce its own cultural artefacts, norms, and values (Schlager & Fusco, 2003). Schlager & Fusco (2003) contend that an effective CoP can enact policies, spread innovation and foster change. They further argue that a significant characteristic of a successful CoP is its ability to flourish, evolve, and reproduce its membership where new members can begin a journey towards mastery and leadership. However, some concerns have been highlighted around the use of CoP. For example, a dysfunctional CoP can have a detrimental effect on a school environment. Rather than driving collaboration, they are hijacked and employed to resist progress, impede innovation or subvert policies (Schlager & Fusco, 2003). In this instance, leadership is essential to ensuring communities of practice are not co-opted in this way.

Co-teaching

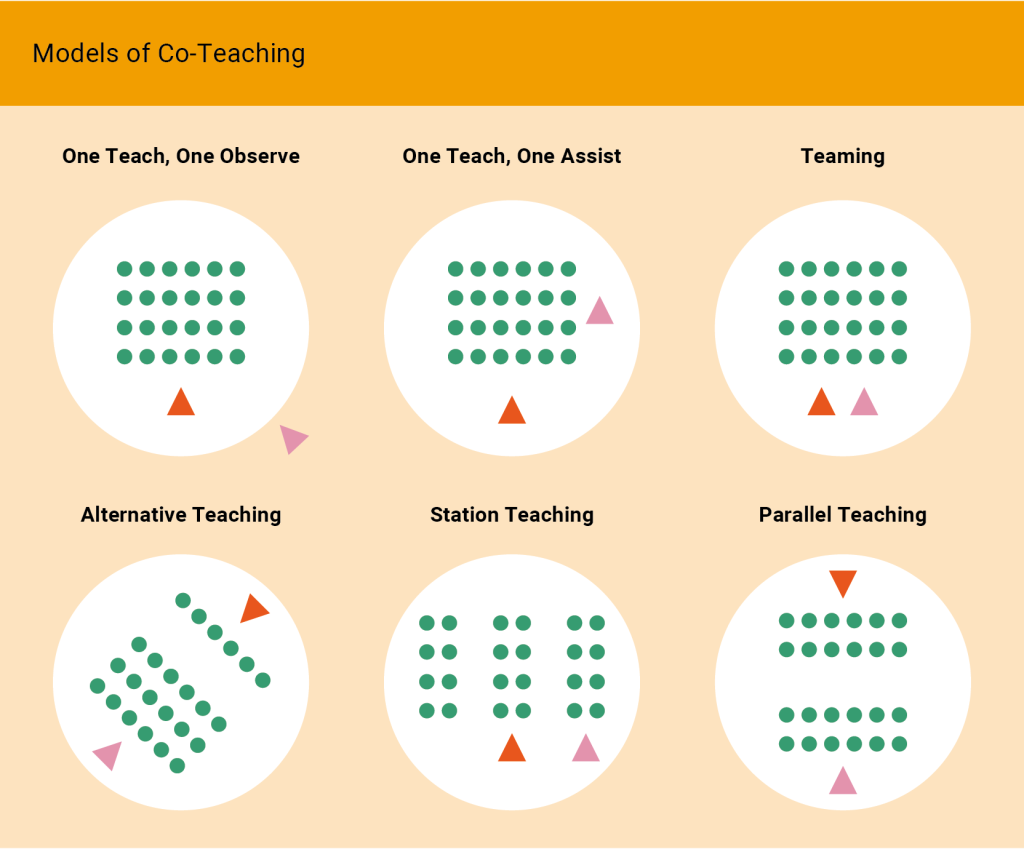

Another means to foster collaboration within a school community is by facilitating and empowering teachers to co-teach (see → Teamwork in the classroom chapter of this book). Firstly, it is important to recognise that there are many models of co-teaching including; whole class team teaching, parallel teaching (with either heterogenous or homogenous groups), one teach and one assist, station teaching, or whole class and small group instruction (Brendle et al.,, 2017; Solis et al., 2012). As co-teaching is an intimate relationship, it requires the teachers to first agree on the model that they will be using. Agreement on the roles and responsibilities before beginning to teach results in better outcomes for both students and teachers who have co-taught (Trent et al., 2003).

Figure 1: Models of co-teaching

After the model is determined, teachers can then collaborate on how to meet the outlined curriculum objectives and execute their plan. The highly collaborative nature of co-teaching draws on the strengths of both the teachers and has been shown to provide positive outcomes for students, specifically those with disabilities (Brendle et al.,, 2017). Co-teaching has also been proven to increase positive attitudes of teachers towards the inclusion of students with disabilities (Solis et al., 2012).

There are many challenges to effective co-teaching such as time and expertise. The role of administrators in advocating and allowing for collaborative planning time is critical to ensure that co-teachers have sufficient time to plan together. It also has been well documented that teachers lack that knowledge of how to effectively co-teach (Brendle et al.,, 2017; Solis et al., 2012, Trent et al., 2003). Further practice and coaching on how to co-plan, co-teach, and co-assess is necessary for the success and positive outcomes to be measured.

Juvonen and colleagues (2019) make similar arguments. They consider challenging the norm and adopting a proactive approach in promoting a culture of social inclusion. Like Killen and Rutland (2022), they also call for the facilitation of interaction among members of diverse groups which helps to reduce negative stereotypes and biases concerning those who are different. Within their classrooms, teachers may also find ways of encouraging inter-group interaction, e.g., through seating arrangements or group work. Interaction across groups may also be encouraged through extracurricular activities or themed clubs which attract students from different backgrounds. It may also be useful to have a peer mentoring system (Juvonen, 2019).

Knowledge

In order for a school to develop an inclusive culture, the educators, administrators, and the school staff must first know about their community and the community that they serve. To know a community requires knowledge about all the dimensions of diversity that affect the unique makeup of that population such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language, nationality, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, geography, disability, and age.

Multi dimensional

The interplay of the different dimensions of diversity is complex and requires an awareness of the implications of certain elements of diversity. For example, as seen in Figure 2, there are elements of someone’s profile (as seen in the inner portion of the wheel) that are more or less fixed and potentially visible to the wider community. There is a recognition here that gender and gender identity may not be fixed, but fluid for some people. The outer portion of the wheel indicates pieces that evolve over time or are not necessarily visible to the outside observer.

Figure 2: John Hopkins University Diversity Wheel

Knowledge of school and wider community demographics is just the first step in this process. It is also necessary to analyse that knowledge to understand how power dynamics affect one’s experience in that community. Fostering and promoting inclusion in a school setting requires knowledge about social exclusion and how to prevent it and address it on different levels (Razer, Friedman & Warshofsky, 2013). As deeper learning is acquired regarding the dynamics of a community, the resulting implications become more clear. For example, if there is a large community of non-religious families in an otherwise predominantly Muslim area, what implications does that have on the inclusion of these families into the school culture?

Fostering and promoting a culture of inclusion may necessitate both direct and indirect interventions and strategies targeting different processes and practices. Educators need constant training and preparation to enable them to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to be able to cater for the needs of all learners as well as to promote values of inclusivity in their everyday practices and interactions at school both with students and colleagues (Mallia Borg, 2007).

In-depth knowledge of the multiple dimensions of inclusion must begin with pre-service teacher training (Bishop & Jones, 2022). As Yuan (2017) states, “It is central to educate pre-service teachers and students in teacher education programs in a culturally responsive way, as well as to facilitate teacher candidates construct effective teaching pedagogies which draw on experiences and knowledge developed in their professional training processes” (2017, p. 3). This knowledge comes from the composition of the community as well as from examination of one’s own background. Whether as an educator, staff member, or administrator, each person brings their own experiences and beliefs with them to the school community.

Learning and developing culturally responsive or inclusive practices does not conclude with pre-service teacher training. While it is important that teachers are exposed early on, it is equally important that it continues throughout a teacher’s career. Continuing professional development is critical for teachers in order to grow their understanding of how to be as inclusive as possible (Carrington and Elkins, 2002; Uçan, 2016). The act of being inclusive is an ongoing process. As the community evolves, so too do their needs, and inclusive school cultures must reflect that. Furthermore, the need for constant evolution does not rest only on teachers, it is necessary that the administrators of the school, as well as school staff and parents, continue to develop their multi-dimensional understandings of their community.

For example, when a community welcomes an increasing number of refugee families over the course of a year, what can be done to understand their cultural or linguistic needs? More recently, there has been an increase in students identifying as LGBTQIA+ and we must question how we can adapt to support their needs. We want to be more inclusive of students with disabilities, therefore what needs to be done to promote more teacher training? What types of programmes do working parents, for example, need to have in order to feel supported?

Members of the community can also be encouraged to explore areas of need within the community. Recognising shifting demographics or evolving concepts in the wider society are essential to having an open attitude towards inclusion, but further research is necessary to fully understand how that change affects a specific school community (Hawkins et al., 2017; Raffo & Gunter, 2008).

Juvonen and colleagues (2019) cite research which shows that when members of minority groups are in larger numbers, the negative effects, such as lower achievement or mental health issues, are reduced. Although this is not possible in many educational settings, it points to the importance of relative student representation (and ethnic characteristics) which may lead to stigma and discrimination (Juvonen et al., 2019). When members of a school community understand this important point, policies can be enacted that reflect the school population and include minority students in the community.

Intentional

An inclusive school culture does not happen spontaneously. There is a great deal of intentionality behind gathering knowledge and using the information to create policies, programs, and practices that foster inclusion and continue to reflect the community that they serve (Carrington & Elkins, 2002). For example, as administrators are intentional about setting up spaces for teachers to collaborate, teachers are proactively seeking to understand the cultural make-up of their new class community or in the instance of the parent community reaching out to new members of the community, we see the thread of intentionality playing an integral role in creating an inclusive school culture.

When an inclusive curriculum is implemented, intentional choices are made including having an understanding of the school’s community characteristics and being committed to including everyone. For example, schools that use Universal Design for Learning (UDL) are one means of ensuring all students, and not just those with disabilities or learning differences, are included and highly engaged (see → UDL chapter of this book).

Intentionality is implicit in the use of language and vocabulary to explicitly include those otherwise marginalised. In the classroom, teachers’ use of inclusive language sends a strong message to students such as respect for students’ preferred pronouns. Gender-neutral language is important in terms of challenging gender inequalities and including students who are non-binary or gender non-conforming (Bastian & Rohlik, 2022). In order for teachers to be able to implement this level of inclusivity in their classrooms, they first must understand their community’s needs and how it works.

We can examine the intentionality of our inclusion by understanding accessibility and what barriers to access may exist for some students. Barriers to access include attitudinal barriers (whether intentional or unintentional), environmental or structural barriers, technological barriers, policy and communication barriers (Pivik, McComas & Laflamme, 2002). When we use this lens to examine what students with a disabilities experience in school, teachers perceptions concerning issues such as lack of access to the classroom or a belief that coursework is too demanding and therefore inaccessible for the student, or that the technology (i.e., screen reader or a assistive device) required by the student is not available, can all prevent inclusion. Viewing barriers to access and participation through an individual’s lens can further promote inclusion.

Another facet of intentional inclusiveness comes from who, and what, is visible and represented in the school environment. This shows a newcomer what is valued in the school community (Ryan, Jerome & Lynch, 1994). Examples of this can be seen by who is represented on the school’s marketing or external communication materials – for instance, is there a variety of races, ethnicities and genders? Are individuals with disabilities visible? What else does the school’s physical environment show us about who is included? Does the physical space demonstrate who is valued here? For instance, accessible bathrooms, parking spaces, classrooms, and offices show that there has been an intentional thought into who makes up this school community. Books and resources that depict multicultural values including different cultures and languages and other visible signs of inclusion. Using culturally responsive teaching practices increases student participation, and has a positive outcome on student achievement as well as the student’s understanding of their own identity (Byrd, 2016; Larson et al., 2018; Piazza et al., 2015). The use of flags – such as pride flags or indigenous flags – can also be an outward sign of the inclusivity of the school culture, provided that they are not used as tokenism, but rather have come from the community (Wolowic, 2017).

Challenges

The greatest challenge is the need to maintain an inclusive school culture. There is a constant need to build knowledge around the evolving nature of a school population. While there are elements of an inclusive school culture that persist over the years, e.g., the policy on inclusion or the ramps and elevators that allow physical access, however, the language used and representations of who makes up a school community will evolve.

The knowledge of legal frameworks and the resulting implications on inclusion within regional or national settings can be challenging. If, for example, there is explicit policy which does not acknowledge one group, religion, or language, it can pose possible legal challenges to how to actively include the entire school population effectively. The policies surrounding education are political by nature and are at risk for change, either to the benefit or detriment of the people, according to changes in political power.

Lastly, maintaining adequate resources is always a challenge. In the case of knowledge building, affording teachers the time, and accompanying financial compensation for their time, to continually increase their knowledge is not always a primary goal for schools given limited budgets. There may not be the financial resources available to purchase materials, equipment, and resources that represent and support the current population of the school.

So, what can a teacher do with these challenges?

Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can. Inclusion may not be big sweeping initiatives supported by a whole school community. Inclusion might be small acts within a classroom of a teacher that welcomes all children in with an open mind and actively builds their own knowledge. Schools play a critical role in reducing vulnerability to exclusion by developing pupils’ sense of self-efficacy, self-worth, and sense of belonging (Raffo & Gunter, 2008) and that can happen on a small scale if necessary until the movement of inclusion grows into a greater school culture.

Leadership

Leadership plays a crucial role in the development of an inclusive school culture (see → Leadership chapter of this book). Zollers and colleagues (1999) contend that an inclusive school culture is born through three key characteristics: a broad vision of the school community, a shared language and values, and inclusive school leadership. They further argue that a thriving school culture may be needed to ensure inclusion flourishes within a school (Zollers et al., 1999). However, creating an inclusive school campus is complex and so often requires a fearless leader (Ainscow, 2001). Strong inclusive leaders explore ways to ensure a collaborative and engaging school environment where everyone is valued, and where staff and students feel safe and have a true sense of belonging. Inclusive leadership’s primary focus is on achieving inclusion and ensuring the necessary processes and goals are in place to achieve that inclusion (Ryan, 2006). Despite what one might think, leadership and inclusion tend not to be mutually inclusive, but instead focuses on a number of factors to create a synergy between them (Ryan, 2006). These include how leadership is understood and planned, and how roles and activities for fostering inclusion are allocated (Ryan, 2006). Promoting and fostering inclusive school culture is a leadership choice, with schools choosing to move in a clear philosophical direction. However, it is often school principals, or the school heads, who are involved in making this decision.

Principals are often viewed as leaders in driving school culture (Francis et al., 2016). Principals are seen as having the most knowledge, access to resources and are in the best position to drive change (Leithwood & Jantzi, 1990). As a result, principals play a key role in the development of inclusiveness ethos within that school culture. An inclusive principal must be morally strong and advocate for inclusion for both staff and students. Evidence suggests that these types of principals are also more likely to support creativity and allow extended levels of risk to be taken (Black & Simon, 2014). Being a leader often requires making difficult decisions. Moreover, promoting an authentic inclusion environment means making daily decisions that include or exclude students and staff (Banks, 2023).

To foster inclusive practices and attitudes, principals should mirror the inclusive practices in their everyday practice. Principals also need to understand, recognise, and value the individuality and diversity of the student population (Ainscow, 2001). They also need to understand that the path to an inclusive school culture is a continuous journey and not a predefined destination. Inclusion is never complete; schools can always learn more ways to be more inclusive. Causton-Theoharis and Theoharis (2008) echo this by arguing that inclusion should be viewed more as a way of thinking than a set school target to be achieved. Moliner Miravet and Moliner García (2013) also contend that two essential components are necessary to foster an inclusive and intercultural culture in schools. These components are a set of objectives agreed on by the educational community and a set of shared values.

However, Ryan (2006) reasons that inclusive leadership is underpinned by a specific set of practices. He purports that these practices include advocating for inclusion, the education of all stakeholders, encouraging debate and discourse, developing critical consciousness, and implementing inclusive decision and policymaking strategies. They also state that inclusive leadership should promote the adoption of whole-school approaches with a particular focus on student learning and classroom practice. Others such as Ainscow (2020) have championed this whole-school approach. The practices mentioned above highlight how inclusive school leadership is very much an intentional process. However, inclusive leadership is only one part of the inclusive culture. For inclusive leadership to have an optimal impact, all stakeholders must promote and support inclusive ideals that foster an inclusive school culture (Ryan, 2006). From a cultural perspective, it is important that leadership examines the cultural needs of not just the students but also parents and teachers alike (Khalifa et al., 2016).

Staff values and attitudes also play an integral role in the creation of an inclusive school culture. Schools need to be staffed by teachers who believe all students can learn and have a responsibility to teach and support every learner (Rose, 2023). These values should include openness and celebration of diversity if teachers are to include and support the participation of every student (Kugelmass, 2003). Sometimes, it is about understanding the climate that is already present within your school. Principals have noted that inclusive leadership can be about knowing what the school’s current baseline is and working from there (DeMatthews, 2021). Moreover, Black and Simon (2014) argue that teachers need to critically reflect on their assumptions and behaviours, inclusive practice and build partnerships with parents and others in the community. They further note how principals are responsible for leading these processes of reflection and collaboration that shape teacher values.

Inclusive practice and the development of an inclusive culture is a shared enterprise. From a sustainability perspective, leadership needs to plan and develop a sustainable approach that commits to the inclusive agenda that is everyone’s responsibility (Black & Simon, 2014). To achieve this goal, a certain level of cooperation and collaborative work is required. This collaboration is at the core of inclusive school cultures and leaders play a critical role in supporting and developing a collaborative culture within a school.

Ryan (2006) states that “for leadership to be genuinely inclusive, it must foster equitable and horizontal relationships that also transcend wider gender, race and class divisions” (p. 8). However, for openness and more fluid collaboration and relationship building, leadership needs to facilitate relationships across both the horizontal and the vertical. These relationships, partnerships and collaborations should not be limited and include, for example, parents, caregivers, teachers, educational professionals, community partners, students and researchers. Collaboration is not a new phenomenon as we can see from examples of co-teaching and communities of practice earlier in this chapter. Many teachers are enthusiastic about working in teams and already collaborate in teams to solve problems, but often they require a strong leader to initiate and support these types of collaborations (Clark et al., 1995). Strong leaders also recognise the need for teamwork, collaboration, and discourse. In addition to collaboration, Banks (2023) notes the influence of dialogue between stakeholders in shaping and reforming inclusive education and practice. Furthermore, collaboration need not be confined within the school. Evidence shows that a school’s capacity to support learner diversity can be better achieved through school-to-school collaboration diversity (Muijs et al., 2011). Likewise, Carrington and Robinson (2006) maintain that a principle of development of a more inclusive school community lies in collaborating and valuing external partners such as parents and the wider community.

School policies have a significant impact on how a school culture and inclusion are created within a school. Inclusive culture requires policymakers and senior staff across educational structures to share similar visions for inclusive education in terms of differences, collaboration and supporting every student. After all, promoting and fostering inclusive practices is everyone’s business, and so all stakeholders, including the students themselves, should be included when developing policy (Ainscow, 2020). However, while the development of policies is one goal, the implementation of these policies is another. There are often inconsistencies about how policies are implemented, so leadership plays a key role in ensuring implementation is successful across the school (Black & Simon, 2014). Ainscow (2020) agrees and notes that policy changes related to inclusion require an effective strategy for implementation to ensure barriers affecting marginalised cohorts are removed. Moreover, all leadership processes should be designed and planned to advocate and support inclusion (Ryan, 2006). Inclusive leaders need to be consistent and clear when it comes to policy. Policies should clearly state what is meant by terms such as inclusion and equity (Ainscow, 2020). However, inclusive school policies that promote inclusive culture may mean little without the resources required to embed a school’s inclusive agenda.

School leadership plays a pivotal role in the acquisition of resources for schools. These include resources that are pivotal to inclusive education, such as aides, technologies and additional staff, including those with specific expertise (Black & Simon, 2014). Shevlin (2023) argues that in an inclusive utopia, schools would have the appropriate resources and accessible spaces so schools could ensure everyone experiences a sense of belonging. However, many inclusive-centric accommodations and supports often require schools to have the financial resources to achieve inclusion, resources schools may not have. Time is another resource often required to accommodate or support a student or colleague in promoting or facilitating inclusive practice. With competing priorities, inclusive leaders need to be proactive and deliberate in acquiring the resources they need. They also need to be cognisant of the additional time often required to facilitate more inclusive agendas and to recognise the value of supporting staff initiatives that focus on creating a more inclusive culture.

From a curriculum standpoint, school leaders must understand that the adoption of inclusive pedagogical frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) or Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) may require the allocation of resources – human, physical and otherwise. These resources include time and formal acknowledgement within performance reviews (Fovet, 2023). It may also have additional financial requirements, such as the acquisition of tools and technologies. However, teachers have identified systematic support from leaders and senior management as essential in obtaining the resources to address barriers to inclusion (Woodcock & Marks Wolfsen, 2019). They also noted the role leadership plays in terms of attitudinal barriers and managing competing demands such as time. Adopting new frameworks requires an understanding of the intricacies of these new approaches. Therefore, knowledge is important when changing inclusive practices and promoting new ways of engagement.

This chapter has already discussed the importance of knowledge in terms of developing an inclusive school culture. However, it is crucial that leaders and senior staff are knowledgeable about inclusive practice and creating an inclusive climate within schools. Worryingly, despite the high level of university-based leadership preparation programs, concerns have been raised about their lack of focus on special education and inclusion (DeMatthews et al., 2020). If leaders are not being trained to understand and mirror the values of inclusive leadership, it may never take hold across educational organisations – a key practice of inclusive leadership. Inclusive leadership needs to be educational as the leader must educate stakeholders across campus on all issues pertaining to inclusive and exclusive practices (Ryan, 2003).

‘Safe space’

Another element that leadership plays a critical role is the nurturing of a ‘safe space’. As noted from the beginning of this chapter, an inclusive school culture can often be an intangible aspect of educational settings, and may be something that is subjectively felt rather than objectively articulated. Inclusive attitudes within collaborative relationships and possession of appropriate knowledge and awareness, guided and resourced by inclusive leaders, can combine to create a school culture that feels safe for all. There is a rich literature dating back to the 1960s on this concept of the intangible ‘felt’ elements of cultures in workplaces using the term ‘psychological safety’ (Schein & Bennis, 1965). This is increasingly being applied to educational settings (e.g. Xie et al., 2022). Equally, there is a range of literature using the term ‘safe space’ that originated in the 1970s in women’s and LGBT movements and which referred to safe physical meeting places. This has more recently been applied to learning environments characterised by respect and safety (Flesner & Von der Lippe, 2019). In this chapter, in recognition of the fact that a truly inclusive school culture needs not just a psychological sense of safety, but also a physical one, we mostly use the term ‘safe space’. However, in defining this intangible element of inclusive school culture we draw on literature that uses either term.

Edmondson, Higgins, Singer and Weiner (2016) state that a sense of safety is particularly crucial in settings characterised by high stakes, complexity, and essential human interactions, and name educational settings as one such type of environment. They indicate that school climate is a key predictor of how people within schools will act, respond, adapt and learn. In schools characterised as safe spaces, individuals feel able to take a risk to try something new or to be themselves. People are able to contribute without fear of being embarrassed or rejected and so within such spaces there is trust, mutual respect and people are comfortable being themselves (Duhigg, 2016). This participation builds a sense of belonging within a community leading to inclusion.

A well-known study on the effects of mutual respect and team dynamics was conducted by the company Google, who explored why some teams were more successful than others. This study, called ‘Project Aristotle’, funnelled millions of dollars into gathering a dizzying array of data measuring almost every aspect of their employees’ lives in an attempt to quantify what constituted the ‘perfect team’ (Duhigg, 2016). They investigated aspects such as how often colleagues ate together, characteristics of effective leaders, gender balance across teams, personality characteristics like introversion and extroversion, and found no common points of data across successful teams or across unsuccessful teams. It was only when they began to investigate the more intangible elements of team culture that they discovered what distinguished successful teams from unsuccessful ones – the way people treated each other. ‘Psychological safety’, broadly defined as people being comfortable expressing and being themselves without fear of embarrassment or retribution, and ‘social sensitivity’ whereby people showed empathy for each other’s perspectives and needs, combined to create inclusive cultures conducive to learning, creativity and success (Edmonson, 2018).

This has implications for inclusive school culture, and it may be the reason that the four elements we identify (attitudes, collaboration, knowledge, and leadership) are so effective in developing inclusive school culture and creating safe spaces for the whole school community. For example, Zhou and Pan (2015) linked psychological safety to transformational leadership and highlighted the necessity of cultures of communication to enhance employee creativity and participation.

There are many problems and difficulties that face inclusive leadership, particularly when it comes to changing cultural norms. The attitude section of this chapter highlighted the attitudinal barriers that must be faced when promoting a more inclusive culture. This leadership section also discussed how policies and financial restrictions might impede the inclusive process. Ainscow (2020) notes how these competing pressures add to the difficulty of developing a more inclusive culture within a school. He further claims that problems around promoting inclusive and equitable school culture stem from three key areas, which focus on issues with schools, issues between schools and issues external to schools (such as family issues and policy-related problems).

Inclusive leadership is paramount in the implementation of an inclusive school culture as it impacts so many facets of the school environment, and models the values of the school or schools it represents. Ryan (2006) contends in order to make the world a better place, schools need to practise inclusive leadership. However, difficulties with inclusive-friendly leadership have been documented and have resulted in a move towards more distributed leadership approaches rather than the traditional hierarchy approach (Ryan, 2006). Ainscow notes that schools must acknowledge that leadership is often the responsibility of a multitude of staff and not just a small number of individuals. For true inclusion, school leaders must foster an inclusive school culture where responsibility for inclusion is everyone’s business, and where an approach based on multiple leaders is encouraged.

Ultimately, moving towards more inclusive ways of operating and thinking takes time and affects an entire school system. However, Ainscow (2020) argues that this can lead to significant changes within schools and classrooms. Additionally, Rose (2023) also notes that to sustain this inclusive change, schools must be respectful of those who are required to implement the change and acknowledge the current climate and culture that exists. After all, inclusive educational change involves dialogue and compassion towards others, but more importantly, a changing of attitudes, actions, beliefs and behaviours, which school leaders are in the optimal position to achieve this inclusive change.

Conclusion

The idea of creating, adapting, or changing a school culture may seem like a daunting task. To make the shift from exclusive to inclusive is not a quick process. It cannot happen in isolation, nor can it be forced on an unwilling participant. There are many interlocking pieces that fit together over time and amongst many members of the community to create a whole school with a commitment to an inclusive culture. Yet each of those cultures starts with one step.

It has been established in this chapter that the attitudes, collaboration, knowledge, and leadership in a school interact to create an inclusive school culture. But the question remains where do you begin? How then does an educator contribute towards the ever evolving concept of an inclusive school culture?

Importantly, teacher training is a key part of this process, yet many teachers feel unprepared or lack confidence on how to effectively include the wide range of students in their classrooms (Florian & Camedda, 2020). This is where the journey of 1,000 steps starts. These are the steps that you begin with today. We can be motivated by the big picture of inclusion, but it can be easy to get discouraged by the enormity of the task and choose not to act at all. Choose to act.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Consider the role that you currently play, or hope to play, in your school culture. What is one thing that you can do to increase the level of inclusion in the school? Where is one area that you can make a change to build a greater sense of inclusion? What is one area that you need to know more about? What are practices that ensure sustainability of inclusive school culture?

- How could you evaluate the effectiveness of inclusive measures in your school?

- What is the most effective way for you to address resistance to building an inclusive school culture?

- How could you foster collaboration with all the stakeholders of your school – the immediate local community, families and caretakers, educators, administrators, staff, specialists, and students?

- What can you, as a student teacher or a pre-service teacher, do now to make your school culture more inclusive?