Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Inclusivity in Outdoor Education

Beausetha Juhetha Bruwer; Victor Tan Chee Shien; and Maria Moscato

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Cases

“When my grandfather passed away a few years ago, he was nearly 100 years old. When he shared stories about his childhood, I was amazed and thought, “Really? You did that? That’s unbelievable.”

Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, Queen Maud University College of Early Childhood Education, Norway

“I remember how we played on my grandfather’s farm as a child. We used to jump off huge rocks and land in a dry riverbed, I can still feel the soft sand under my feet. We would climb on huge rocks and pretend they were the aeroplanes we saw above us, taking us to a strange land where we could play all day.”

Beausetha Bruwer, University of Namibia, Namibia

“Growing up in the concrete jungle of Singapore, my connection with the outdoors was very much associated with a sense of adventure. I caught spiders at the cemetery, the few places that actually had greeneries, and fishes in the drainage in my own little adventures. Those little ‘adventures’ led my curiosity in understanding the world around me even now.”

Victor Tan Chee Shien, University of Stirling, UK

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is the purpose of Outdoor Education?

- How can Outdoor Education be inclusive?

- What to prepare for Outdoor Education?

Introduction to Topic

Reflecting on Outdoor Education (OE) reveals its significance as a fundamental educational necessity, rooted in the philosophies of influential thinkers like Locke, Rousseau, Pestalozzi, Fröbel, Montessori, and Dewey, who advocated for fostering individual autonomy from early childhood (Bortolotti, 2014). Extensive national and international literature supports OE as a multifaceted approach, recognising the outdoor environment as an active and essential component of the educational experience (Farné, Bortolotti, Terrusi, 2018).

Outdoor activities can be understood at multiple levels. At its most basic, it involves teaching activities typically done in a classroom but conducted outside with minimal environmental interaction. At a deeper level, they enhance learners’ understanding of their environment through direct engagement. At its most profound, it is a pedagogical approach that uses the outdoors as a rich, experiential setting for authentic learning across various domains (Kelly et al., 2022). Learning outside the classroom significantly benefits learners’ overall curriculum learning. Learners who struggle in traditional indoor classrooms often thrive in outdoor settings, as they tend to be less distracted and more focused. The hands-on and interactive nature of outdoor activities, combined with regular breaks, helps maintain learners’ engagement (Kelly et al., 2022). This stimulates both emotional and cognitive processes, creating ideal conditions for the development of metacognition.

Inclusion remains a central aspect of OE, with outdoor settings being particularly effective in fostering welcoming, cooperative, and supportive environments, thus promoting positive social interactions. Being in natural settings helps build a sense of community, strengthens feelings of belonging and respect, and deepens connections to life and the environment, nurturing an ecological mindset (Bortolotti, Schenetti & Telese, 2020; Brodin, 2009). However, inclusion in OE presents significant challenges, such as ensuring that activities are appropriate for the diverse needs of learners and balancing adventure and unpredictability with safety (Rickinson et al., 2004). In this regard, research highlights the crucial role of educational intentionality in obtaining positive results from OE programmes. In this context, teacher training is vital: teachers must acquire both an open and flexible professional posture and specialised skills to design and manage outdoor activities to guarantee that educational practices are impactful, inclusive and secure. Additionally, parental involvement is crucial for the success of outdoor educational experiences. Parents need to be well-informed and engaged in the educational processes, recognising the benefits and opportunities these experiences can offer their children (Epstein, 2018).

Considering these foundational principles and the intricacies involved, this chapter will explore key aspects that underscore the wide-ranging benefits of OE in shaping well-rounded, environmentally aware, and socially responsible individuals. These key aspects highlight the teacher’s vital role in fostering a safe, inclusive, and enriching outdoor learning environment that promotes the holistic development of learners.

Key aspects

Purpose of Outdoor Education and Why It is Inclusive

John Dewey (1916/2004) particularly advocated for education as a liberating and democratic process, rather than a passive activity controlled by authority figures. Dewey posited that human adaptation to the environment is characterised by active engagement rather than simplistic conformity. He argued that just as ‘life’ is not a passive existence but a mode of action, the ‘environment’ either stimulates or inhibits this activity. Consequently, education occurs indirectly through environmental interaction. Hunt (1995) elaborates on Dewey’s distinction between ‘primary experience’ – the initial, unprocessed encounter – and ‘secondary experience’, which emerges from reflection, lending clarity and meaning to these encounters. These principles form the foundation of OE, which posits that meaningful learning begins with the bodily engagement of the learner in an environment. This involves practical activities and reflective moments, during which learners, often guided by a teacher, strive to comprehend and derive meaning from their experiences.

This approach delineates the distinction between Outdoor Learning (OL) (synonymous with Experiential Learning) and OE (equivalent to Experiential Education). OL primarily focuses on acquiring practical skills and knowledge, often tied to specific objectives. While all learning is experiential to some degree, it is not always intentionally designed as such. Conversely, OE involves deliberate learning design through two key elements: crafting experiences for learners and facilitating these experiences through reflective practices. Dahlgren and Szczepanski (2005) observe that whilst experiences are inherently specific and contextual, reflection is crucial for transmuting these experiences into knowledge. They assert that OE, with its unique characteristics and identity, possesses significant potential to enhance meaningful learning. This potential is realised when there is a conscious educational awareness guiding the process. Consequently, OE centres on targeted educational interventions that explore both learning and individual identity formation. These interventions assist individuals in discovering and developing their personalities, transcending mere participation in activities. Additionally, OE fosters an environment where living and growing are intertwined, facilitating learning through a dialectical process in which each moment contributes to the whole. By taking education beyond the confines of traditional school walls, OE promotes a holistic vision of learning. In this paradigm, direct environmental experiences play a pivotal role in personal development. OE aids individuals in forming a worldview that informs their interpretation of both their own lives and the world at large (Chistolini, 2016; Wattchow & Brown, 2011).

Mortlock (1987) and Loynes (2002) emphasise the importance of the “inner journey” in OE. The inherent unpredictability of outdoor experiences cultivates adaptability and enables learners to uncover their personal capabilities. OE should be viewed holistically, integrating not only rational, functional, and practical elements but also perceptual experiences that foster personal growth. Hopkins and Putnam (1994) identify three key elements in OE: ‘self’, ‘others’, and the ‘natural environment’. The self focuses on individual development through adventurous activities. The others concern the cultivation of group cooperation and effective social structures. The natural environment presents myriad challenges, enabling participants to augment their knowledge and understanding of nature. Brodin (2009: 100-101) notes that the authors “highly stress the value of OE primarily as a learning resource. They emphasise leadership, team-building and problem-solving as some of the benefits. Knowledge and awareness of nature will grow at the same time as the participants get physical challenges.” In essence, OE transcends the mere act of venturing outdoors; it primarily concerns an openness to perceptions and sensations that ‘exceed the threshold’ (Mazza, 2018). This facilitates new connections between self, others, and the world (both organic and inorganic), delineating a learner-centred educational model of a highly relational nature, in which environmental and social contexts play crucial roles (Waite, Bølling, & Bentsen, 2016).

Once again, the crucial distinction between Experiential Learning and Experiential Education within the realm of OE comes to the fore: Experiential Learning, on the other hand, encompasses processes where the individual internally assimilates and reflects upon experiences. In this paradigm, learning and debriefing can occur within the learner’s mind, without necessarily requiring external articulation or shared discourse. Experiential Education, on the other hand, with which OE is more closely aligned, necessitates that learning be externally expressed and collectively shared (Joplin, 1995). This public dimension is paramount in OE: what constitutes ‘experience’ is not merely the isolated event itself, but rather the synthesis of personal cognitive processes with public acknowledgement and validation of the experience. This distinction is pivotal, as it underscores a core tenet of OE: the emphasis on collective learning and shared meaning-making. In OE, experiences are not solely processed individually but are brought into a communal space for discussion, analysis, and integration into a broader understanding.

In essence, the alignment of OE with Experiential Education highlights its commitment to collaborative learning, shared reflection, and the development of collective understanding. This approach not only enriches individual learning experiences but also contributes to building a more inclusive and interconnected educational environment, moving beyond mere individual competitiveness towards a more holistic and socially conscious form of education. OE, therefore, represents education in, about, and for the environment, aiming to ensure learners’ autonomy of action and relationships, capable of attributing meaning to both their context and the role played by individuals and communities within it (Quay & Seaman, 2013).

Immersive engagement with the real world and the strategic utilisation of the environment as an educational resource foster a continuous learning process rooted in mutual support. This approach is facilitated by innovative methodologies, such as Problem-based Learning (PBL) and Collaborative Teamwork. Consequently, it broadens educational horizons and cultivates essential skills for addressing global challenges, thereby shaping informed citizens and resilient communities. In this context, OE transcends the boundaries of a mere educational method, evolving into a life philosophy that actively promotes authentic participation. Open spaces emerge as powerful catalysts for nurturing a sense of belonging, fostering cooperative relationships, and encouraging mutual assistance. These elements collectively contribute to positive socialisation among individuals and groups (Brodin & Lindstrand, 2006; Gair, 1997; Magnusson, 2006). It represents a paradigm shift in educational philosophy, recognising the intrinsic link between personal growth, community development, and environmental engagement. This approach in OE addresses the need to transcend what Biesta (2006) terms learnification – the tendency to view learning and education as predominantly individualistic processes aimed at creating high-performing actors in a competitive system. Instead, OE, through its emphasis on shared experiences and public reflection, promotes education as a process of mutual construction and recognition, fostering holistic human development. Thus, OE not only enhances the learning experience but also contributes to the development of a more inclusive and interconnected society.

Recent evidence-based studies (Mitchell, 2013) elucidate the intrinsic connection between inclusive education and OE. Both paradigms emphasise the crucial relationship between individuals and their environmental context, aiming to promote environmental, relational, and social sustainability. In this framework, inclusion is conceptualised not as an end goal but as an ongoing process that permeates various spheres of an individual’s life, including educational institutions, family environments, and broader social contexts (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Inclusive education extends beyond the mere removal of learning barriers and anti-discrimination efforts. It actively seeks to engage all learners, valuing and enhancing diversity. This perspective transcends the traditional dichotomy between ‘normal’ and ‘special’, adopting a holistic approach that promotes full, active participation of all individuals in authentic contexts (Florian & Beaton, 2017; Pedone, 2021).

These principles seamlessly align with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015), which underscores the importance of harmonising economic growth, environmental conservation, and social inclusion. This approach aims to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own (WCED, 1987). Implementing these principles necessitates a profound cultural shift in educational contexts, requiring continuous reflection and intentional transformation (Bufalino & D’Aprile, 2021). OE can play a pivotal role in facilitating this transformation through its emphasis on environmental connection and interaction.

Let us pause and reflect

- What is your idea of Outdoor Education?

- What role can local communities and natural environments play in education?

- How do you think the surrounding environment can influence learning?

Engagement with the Environment

Example 1

In essence, OE aims to foster learning through concrete experiences and reflections in authentic contexts. This approach extends beyond the mere transfer of learning to natural, cultural, and social environments, encompassing several key aspects:

- The concept of extending the learning space beyond traditional boundaries.

- The construction of connections between sensory experiences and theoretical content.

- A focused attention on context, viewed as both place and space, serving as both object and subject of the educational process (Center for Environmental and OE, 2004, cited in Szczepanski, Malmer, Nelson & Dahlgren, 2006).

Higgins and Nicol (2002) emphasise that spaces outside the school can serve as invaluable educational environments, promoting cooperative and personalised learning. This is achieved through the intentionality of teachers who adapt training opportunities to local specificities and diverse learning styles. OE does not simply relocate the classroom outdoors; rather, it aims to create a dynamic interaction between emotions, actions, and thoughts. This approach fosters learning that values curiosity and continuous discovery, creating a holistic framework that guides the teacher’s intentional action toward leveraging the unique characteristics of the surrounding environment. It avoids the fragmentation of information, instead promoting an integrated and in-depth exploration of themes. Utilising outdoor educational experiences, mediated by relationships and shared reflection, stimulates the use of all senses and creates a learning climate particularly suited to content best assimilated outside school walls. This facilitates the integration and enrichment of the curriculum in an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary manner, supporting both individual and community, personal and social development (Zanato Orlandini, 2020).

OE firmly links the learning process with real experiences, relationships, events, and conditions provided by the environment. This approach aligns with the intrinsic values of Place-based Education (PBE), which allows for the exploration and appreciation of the cultural and natural characteristics of territories, transforming them into laboratories for personal and social growth (Brown, 2008). As Sobel (2004) highlights, PBE emerges as a response to the lack of attention to local environments in many schools. It underscores the importance of local communities and natural environments in encouraging practical and respectful learning and forming responsible citizens and democratic communities. This involves identifying learning contexts within one’s local geography – be it a portion of nature, a part of the city, a park, or a square – that are proximate, accessible, practicable, and generally free and available (Perfetti, 2023). Through the active engagement of local citizens, community organisations, and environmental resources in school life, it activates a generative dialectic that brings education back into the community and involves the community in education.

In summary, rather than being confined to studies of distant places, this approach utilises the community and its surroundings as a starting point for teaching subjects such as language, mathematics, social studies, and science. This helps to enhance academic performance, strengthen learners’ bonds with their community, increase appreciation for the world, and encourage active engagement in society. Ultimately, it promotes the improvement of community and environmental quality (Gruenenwald & Smith, 2008).

Let us pause and reflect

How can a place-based educational approach affect the development of values and skills related to responsible citizenship and active social participation?

Benefits of Outdoor Education

Example 2

“At the school camp conducted annually, learners are split into fixed mixed-gender teams of 8 for the week long event. At age fourteen, the physical difference between males and females was becoming increasingly obvious. A few teams started to express concerns that having more girls on their team would put them at a disadvantage. While I usually encourage learners to manage group dynamics on their own, I recognised this as an important teaching moment. I brought the class together for an open discussion about the possible tasks they might encounter during the camp, emphasising that the camp’s goal is to develop interpersonal skills like teamwork, leadership, and situational problem-solving, which require a diverse set of skills and aptitude rather than a bulldozing mentality.

“It’s crucial to have a diverse set of skills for any task, rather than assuming that having all boys or all girls on a team offers any advantage. Just like in real-life situations, we won’t always have all the answers, and that’s okay. We should recognise this, not as a weakness, but as an opportunity to seek help from others, regardless of who they are. Everyone has different abilities and strengths, regardless of height or gender. After all, I don’t see Gal Gadot (Wonder Woman) or Henry Cavill (Superman) here, do you?”

Following this discussion, the group were asked to break out and reflect on their individual and collective strengths.”

Victor Tan Chee Shien, University of Stirling, UK

The scenario above captures how outdoor spaces can serve as an effective teaching context by offering authentic and critical learning opportunities. The teacher in the scenario used the annual outdoor school camp to create awareness among his intermediate group of learners about gender diversity and sensitivity. Thus, OE is more than just imparting knowledge outside of traditional in-class learning, it is all-encompassing in promoting growth and development on many levels. Learners who participate in outdoor activities improve their problem-solving skills, gain useful knowledge through real-world experiences, and become more resilient in the face of adversity (Cenić et al., 2023). Through OE, learners get a unique opportunity to deepen their knowledge and comprehension through hands-on experiences outside of the classroom. These outdoor experiences allow learners to understand concepts in diverse ways, such as through listening, taste, touch, sight, and smell, as well as through aesthetic, emotional, intellectual, physical, and spiritual experiences (Neville et al., 2023; Stavrianos & Pratt-Adams, 2022). When classrooms or outdoor play areas are designed to meet each learner’s sensory, motor, behavioural, social, and emotional needs, they enhance and broaden growth opportunities (Brodin, 2009).

Play activities are crucial for learners of all ages to explore and understand themselves while developing essential physical traits for overall health and well-being. Risky play, for example, is a novel approach to introducing OE. According to E. Sandseter (personal interview, March, 2024), risky play involves learners intentionally taking risks to challenge themselves, test their limits, and explore their capabilities. This type of play is often physical and exciting due to its unpredictability, though it carries the risk of injury or accidents. The benefits include the thrill and range of emotions it provides, from exhilaration and fear to sadness if hurt. Learners are naturally drawn to risky play because it elicits positive, thrilling emotions. Successfully managing these risks can lead to a strong sense of mastery (Sandseter, 2009). Risky play greatly benefits learners’ learning and development, offering valuable experiences and fostering emotional growth.

The learner must always be prioritised as the central focus. Therefore, understanding their backgrounds, as well as the conceptions and misconceptions they bring to the learning environment, is essential for optimising OE outcomes (Neville et al., 2023). The same as in classroom teaching, not all learners will participate in the same activities during OE. Thus, the teachers will need to use their knowledge of the learners to tailor tasks, promote inclusion, and encourage learner autonomy. According to Neville et al. (2023), this approach will enable learners to make and act on choices that positively impact their lives, helping them independently recognise the benefits of OL.

Parker (2022) identifies several key benefits of integrating OE for learners. Recognising these benefits in relation to individual learners’ needs can help teachers choose the most suitable outdoor activities for their learners. These benefits include Health and Well-being, Children’s Physical Development; Mental Health; Social-Emotional and Cognitive Development; Academic Benefits; Behavioral Improvements; and Enhanced Memory.

Health, Wellbeing and Children’s Physical Development

According to Parker (2022), OE can generate numerous health benefits for learners participating in outdoor programmes. These benefits include improved air circulation, higher oxygen levels, better sleep, and increased Vit D exposure to sunlight. Increased vitamin D levels are also linked to improved bone health, cardiovascular health, and more effective insulin regulation. Harper (2017) agrees that time spent in natural environments provides substantial health benefits, such as physiological improvements, quicker recovery from mental fatigue, injury, and illness, increased life satisfaction, and improved stress management. To counteract the growing prevalence of hypokinetic diseases like obesity and diabetes and address sedentary habits caused by increased screen time, it is advisable to encourage active outdoor activities in children.

Mental Health

Parker (2022) notes that children with access to greener environments display lower aggression and violence and experience less mental stress. Simply viewing nature has been found to reduce physiological stress responses, increase interest and attention, and decrease feelings of fear, anger, or aggression. Accordingly, Harper (2017) reports that, through the incorporation of outdoor activities, children from vulnerable backgrounds, such as those from disadvantaged neighbourhoods or who have experienced homelessness, abuse, or substance use, also showed improvements in well-being and resilience.

Social-emotional and Cognitive development

In addition to physical benefits, OE supports learners’ social, emotional, and cognitive development by enhancing creativity, problem-solving skills, independence, and confidence. Regular exposure to natural environments boosts children’s cognitive abilities, and children with, for example, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) show better concentration and rate their experiences more positively outdoors compared to traditional classroom settings (Parker, 2022). Additionally, OE promotes inclusion, teamwork, and social skills development among learners by fostering high levels of participation and collaboration. It is particularly beneficial for learners with learning difficulties, enhancing their community presence, active participation, and competence. Group work in outdoor settings encourages intimate interactions, team building, and collective goal achievement (Stavrianos & Pratt-Adams, 2022). Furthermore, outdoor environments provide diverse learning opportunities that help children form ideas, values, and environmental consciousness from a young age. Activities like environmental games can motivate learning by sparking interest and addressing knowledge gaps (Stavrianos & Pratt-Adams, 2022).

Academic Benefits

Parker (2022) finds that learners who engage in OE programmes outperform their peers in various assessments, including math and science. Furthermore, these learners exhibit higher attendance rates compared to those not involved in OE. Cenić et al. (2023) also highlight research suggesting that spending time in nature positively influences learners’ cognitive functions and their interest in learning. Interaction with nature enhances collaboration and problem-solving skills while simultaneously boosting learners’ happiness, well-being, and motivation. These benefits can lead to increased classroom engagement, potentially improving overall learning achievements. This evidence underscores the importance of integrating natural elements into the educational process as a valuable factor in supporting cognitive development and learner education.

Behavioural Improvements

OE can significantly improve school attendance and provide a sense of achievement for children with emotional or behavioural disabilities, counteracting the negative effects of repeated failure in traditional educational settings. Its strength lies in creating inclusive activities that accommodate all children, allowing them to participate at their own pace (Stavrianos & Pratt-Adams, 2022). Learners who find traditional classroom settings challenging may greatly benefit from personalised OE experiences. Instead of struggling with motivation, confidence, attention, or social skills in the classroom, these learners can develop these skills through OE. They often thrive and even take on leadership roles during hands-on outdoor activities (Parker, 2022).

Enhanced memory

The memory of the context and experience of OE can be more impactful than the specific educational content intended to be taught. According to Parker (2022), for some learners, the memorable aspects of the visit, such as the sounds, sights, or even objects like pebbles, are as significant as the factual details learned at the location.

Teachers can adapt their methods to be more inclusive by using natural contexts and local places in their teaching. This approach incorporates a variety of skills, equipment, and experiences, ensuring that all learners, regardless of their differences and abilities, can participate and benefit from outdoor learning.

Challenges in Outdoor Education

Despite the advantages of OE, several challenges impede its implementation. A significant obstacle is the stigma that OE is not considered “real” teaching, which affects its adoption (Parker, 2022; Stavrianos & Pratt-Adams, 2022). Effective implementation of OE necessitates extensive planning and coordination to meet educational objectives. Teachers play a crucial role in shaping and evaluating the effectiveness of educational methods, including OE. From the teacher’s perspective, this involves planning and organising field activities, adapting teaching strategies and resources, and managing learner groups. Teachers are essential for the successful execution of OE, as they must ensure learner safety, motivate learning, and maximise the benefits of the outdoor experience. They need to be knowledgeable in their subject areas while being adaptable to changing conditions and learner needs during outdoor activities (Cenić et al., 2023).

An interdisciplinary approach to education supports the holistic development of learners by fostering creativity, curiosity, and self-confidence, with the integration of various fields of knowledge being a central aim of holistic learning. Outdoor activities play a pivotal role in this process by allowing learners to connect theoretical knowledge with practical experiences in a natural or urban setting. Thus, incorporating these activities into the teaching process is essential but challenging (Cenić et al., 2023).

Parker (2022) notes that teachers may lack confidence in outdoor teaching due to limited experience and knowledge. They encounter challenges such as restrictive curriculum demands, insufficient time, and a lack of inspiration or structure. Broader issues, including work pressure, excessive responsibilities, and fatigue from frequent educational changes, also impede OE. Additional barriers include concerns about losing control, health and safety issues, inadequate administrative support, traditional teaching perspectives, and inflexible schedules. Furthermore, parents may resist OE, particularly for children with special needs, due to concerns about external judgments regarding parenting and fears about potential harm to their children (Harper, 2017).

Neville et al. (2023) further note that opportunities for OE are often limited by an emphasis on evidence-based outcomes and standardised testing, which narrows the curriculum and prioritises test preparation. Its implementation is also influenced by school interests, teacher expertise, and the quality of pre-service teacher training, but is constrained by time limits, strict learning objectives, and unfamiliarity with outdoor teaching.

To address these challenges, OE should be recognised by all stakeholders as a legitimate method to expand curriculum resources. Clear examples of curriculum integration are essential to encourage teachers to adopt this approach and promote learner success. The recognition would increase institutional support and drive teachers’ training.

Preparation for Outdoor Education

Teacher training

As Wolf, Kunz and Robin (2022) point out, OE is becoming increasingly relevant in formal school education due to the benefits found in terms of teaching practice and the well-being of teachers and learners. However, the effective implementation of this approach is hampered by the lack of specific training for teachers.

An interdisciplinary curriculum, on which OE is based, requires a systematic dialogue between different disciplines and methodologies, which cannot be improvised in a purely experiential context. In this regard, Zanato Orlandini (2020) highlights the importance of an intentional educational approach rather than mere casual exposure to the natural environment as the main source of learning. The author warns against considering the outdoor experience alone as a guarantee of meaningful learning since mere contact with the external environment is not enough to gain an in-depth understanding of natural and cultural phenomena. The design of quality OE experiences must be carefully planned, taking into account the specificities of the environmental context and the needs of the learners.

From an operational point of view, OE is expressed through the action of the teacher, who translates into practice their intentionality, vision, values and implicit curriculum. By doing this, the teacher creates a mix of skills and personal traits that do not consist of a simple sum of disconnected elements but must be understood in holistic and global terms, forming a structured and multidimensional whole of effectiveness. The teacher must not only use knowledge and skills but also take responsibility for their work to adapt, innovate, integrate different knowledge and manage complexity. Educational action goes beyond technique: it is a meeting point where theory, practice and reflection illuminate each other and find concrete application. A holistic model of professional competencies therefore includes not only knowledge and skills but also attitudes and values essential for the development of professional identity (Pedone, 2021).

For these reasons, teacher training for OE must be characterised in a holistic and multidimensional way, including an in-depth preparation that covers the pedagogical, value, and practical attributes of outdoor teaching.

Let us examine some of its aspects:

- Importance of beliefs and training needs: Farnè and collaborators (2018) state that the difficulties in achieving quality education are not always linked to structural limitations, but often derive from the lack of adequate tools or skills. It is therefore crucial to focus on teachers’ primary training needs, which may be hidden behind secondary training needs. If, for example, teachers experience difficulties in integrating OE with standard curricular requirements or in adapting outdoor activities to learners’ different skill levels, these secondary needs may reflect a lack of training in instructional differentiation strategies. This suggests a primary training need: adequate preparation in the design and personalisation of outdoor educational activities. It is critical that OE training includes not only specific techniques for outdoor teaching but also ways to integrate these experiences with the curriculum and tailor them to the needs of learners, ensuring inclusive and effective activities.

- Developing Positive Attitudes and Personal Outdoor Experiences: Teachers’ attitudes towards OE play a crucial role in the success of training, as their dispositions and perspectives significantly influence their approach and willingness to adopt innovative educational methods (Nicol, Higgins, Ross, Hamish & Mannion, 2007). The literature highlights that teachers who demonstrate greater openness to OE often have significant and positive personal experiences outdoors. These experiences can help develop an ‘outdoor dimension’ that is essential for effective OE implementation.

Positive outdoor experiences help teachers:

- Understand and appreciate the value of OE.

- Assess risks more effectively.

- Build confidence in their abilities to meet challenges.

These factors are fundamental for developing a positive attitude towards OE, as they allow teachers to recognise and value the pedagogical sense of adventure and risk-taking (Farnè et al., 2018; Wolf et al., 2022). To convey a positive attitude towards the environment to learners, teachers need to feel comfortable outdoors. They must be able to assess and manage risks, ensuring safe and positive experiences. One effective way to develop these skills is to include training courses in external environments in both the initial and ongoing preparation of teachers. This approach allows teachers to directly experience the activities they will propose to learners, thereby:

- Enhancing their comfort level in outdoor settings.

- Improving their risk assessment and management skills.

- Developing a deeper appreciation for the educational potential of outdoor spaces.

Moreover, this hands-on approach to teacher training can also support education for sustainable development, which should integrate outdoor experiential techniques (Nicol, Rae, Murray, Higgins & Smith, 2019). By experiencing OE firsthand, teachers are better equipped to:

- Design and implement effective OE experiences.

- Integrate OE principles into their overall teaching practice.

- Foster a sense of environmental stewardship in their learners.

Fostering positive attitudes towards OE through personal outdoor experiences should be a core component of teacher training programmes. This approach not only enhances teachers’ skills and confidence but also contributes to the broader goals of environmental education and sustainable development.

- Integration of Pedagogical and Content Skills: Training for OE must combine in-depth knowledge of pedagogical content with specific skills for outdoor teaching. Dyment, Chick, Walker and Macqueen (2018) emphasise that it is essential to be able to translate disciplinary knowledge into effective teaching practices. In this context, the ‘knowledge quartet’, which includes the transformation of knowledge into teaching modalities, the connection between themes and the coherence of lessons (Rowland, Huckstep & Thwaites, 2005), is particularly relevant. In the context of teaching, specialist professional knowledge must include not only the domain of the subject (a fundamental element) but also a general understanding of teaching and learning methodologies (general pedagogical knowledge). In addition, as described by Shulman (1987), it is crucial to possess what is called ‘knowledge of pedagogical content’ – i.e., the competence to convey content effectively to learners. This model implies that teacher training for OE must not be limited to mastery and transmission of content, but must instead also include skills in the design and management of outdoor educational experiences, along with a wide range of knowledge regarding curricular structures, teachers’ legal responsibilities and other related issues.

- Development of Flexibility and Adaptation Skills: Outdoor teaching requires a level of flexibility and adaptation that goes far beyond that required in traditional educational settings. Outdoor environments, with their variable and unpredictable conditions, pose unique challenges that require teachers to adapt quickly and effectively. This ability to adapt is crucial to take advantage of learning opportunities that may emerge unexpectedly and to respond appropriately to environmental changes and learners’ needs (Greenwood, 2013). To prepare teachers for these challenges, OE training must include hands-on exercises and simulations that reflect the real-world conditions in which they will operate. Through such experiences, teachers can exercise their ability to handle unexpected situations, make quick decisions, and take advantage of the learning opportunities that the external context offers. These exercises should be designed to simulate various scenarios, from adverse weather conditions to the need to adapt activities to different group dynamics, allowing teachers to develop strategies for dealing with uncertainty and change.

- Reflective Skills and Critical Approach to Teaching Practice: To build a professional profile of this type, it is essential to approach training as a shared journey of discovery, where each teacher is encouraged to adopt a research perspective on their professionalism, embracing reflective thinking. This reflection is not an end in itself but arises from the continuous dialogue between theory and practice, enriched by the comparison with colleagues (Clayton, Smith & Dyment, 2014). Reflective practice is a dominant concept in teacher education and is widely applied in initial education programmes (McGarr & McCormack, 2016) and in-service teachers in many parts of the world (Harford & McRuaric 2008; Nizet, 2016). During the training process, teachers must be guided to critically reflect on their experiences, evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching strategies and identify areas for improvement. Critical reflection is not just an occasional practice, but an ongoing process that involves analysing the feedback received, self-analysing one’s practices, and modifying strategies in response to experiences in the field. Such reflection helps teachers develop a deeper understanding of the dynamics of outdoor teaching and improve their ability to respond effectively to daily challenges. To integrate critical reflection into initial training, it is helpful to include activities such as guided discussions, reflective journals, and peer feedback sessions. These tools help teachers explore their experiences and draw meaningful lessons that can be applied in the future. In addition, the support of experienced mentors and participation in communities of practice can provide additional opportunities for reflection and professional growth.

Blenkinsop, Telford and Morse (2016) have identified five key areas of reflexivity that are particularly useful when thinking about OE:

- The teacher’s self-analysis: Questions such as “How am I improving my understanding of this context?” or “Why do I choose to do X instead of Y right now?” help to explore personal motivations.

- Focus on learners: Both as individuals and as a group, with reflections such as “What did I notice today?” or “What is the next logical step for their learning?”.

- Co-reflection: Involving learners, parents and other teachers to obtain different perspectives.

- The role of the environment: Considering questions like “How has the place influenced our practices?” or “Have I been able to integrate the natural environment?”.

- The broader learning community: Assessing how school infrastructure and cultural systems support or hinder outdoor work and what traditions or metaphors are emerging.

To get the most out of OE experiences, reflection should go beyond simply checking lesson results. Exploring these areas helps teachers improve their practice with a deeper, more mindful approach (Neville, Petrass & Ben, 2023). Effective teacher training for OE requires a comprehensive approach that addresses not only practical skills but also pedagogical knowledge, attitudes, and reflective practices. This holistic approach ensures that teachers are well-equipped to deliver meaningful and impactful outdoor educational experiences, fostering both their professional growth and the holistic development of their learners.

Let us pause and reflect

- What do you think would be the main benefits of Outdoor Education for teachers?

- What is the importance of critical reflection for a teacher practicing Outdoor Education?

- How can a holistic approach to teacher training improve the quality of Outdoor Education?

Risk management

For any educational activity, planning and preparation are necessary to make the best of the lesson. Lessons outdoor, or OE are no different for risk management. As with any lesson preparation, the learning objective and the learner’s needs are the focus. Where an authentic experience carries with it some level of risk, thus, preparations to control the risk are inevitable, similar to any form of material or planning preparation required for any type of lesson. A common misunderstanding with outdoor lessons is that they are high-risk activities disregarding learners’ safety. These misunderstandings do not account for the purpose of the learning and the value that these experiences can bring to maximise learning. Risk is a real concern, but research has shown that risk aversion has negative consequences in development across all stages (Dickson & Gray, 2012; Paulsen et al., 2012). While not promoting risk-taking in itself, it is important to consider the value of the learning experience in which omission of all risk is simply impossible.

Example 2

“It is a warm day, too hot to sit in a kindergarten class for deaf and hard-of-hearing learners. The teacher took the learners to a nearby park from the school premises. Before the walk to the park, the teacher showed the learners pictures of different local transport, discussed the signs with the learners, and asked them to spot how many different transports they saw on the walk. Learners were taught to recognise signs and make use of available traffic infrastructures to ensure their own safety. The key to the lesson is to build an able learner that can traverse the environment safely in a controlled activity.”

Beausetha Bruwer, University of Namibia, Namibia

The scenario presented above highlights the value of the experience over the risk involved. While there are inherent risks to a guided walk to the park, the value of the learning experience presents in that learners cannot avoid the risk associated with transit forever. There is value in risk, which must be controlled by the teacher, similar to any lesson preparation. Teachers employing OE concepts must engage with risk management as part of their lesson preparation to reduce risk. These preparations usually comprise a risk assessment document and an eventual consent form for participants. Clear and specific risk management documentation can be used to convince stakeholders, such as school management and policymakers, of the value of the outdoor lesson despite the risk involved (if any). Parents and participants are important stakeholders in education that need to be engaged as part of education. Not only are parents custodians of their child’s participation, but youth-adult participants can also be engaged in pre-activity through a well-designed consent form (David et al., 2001).

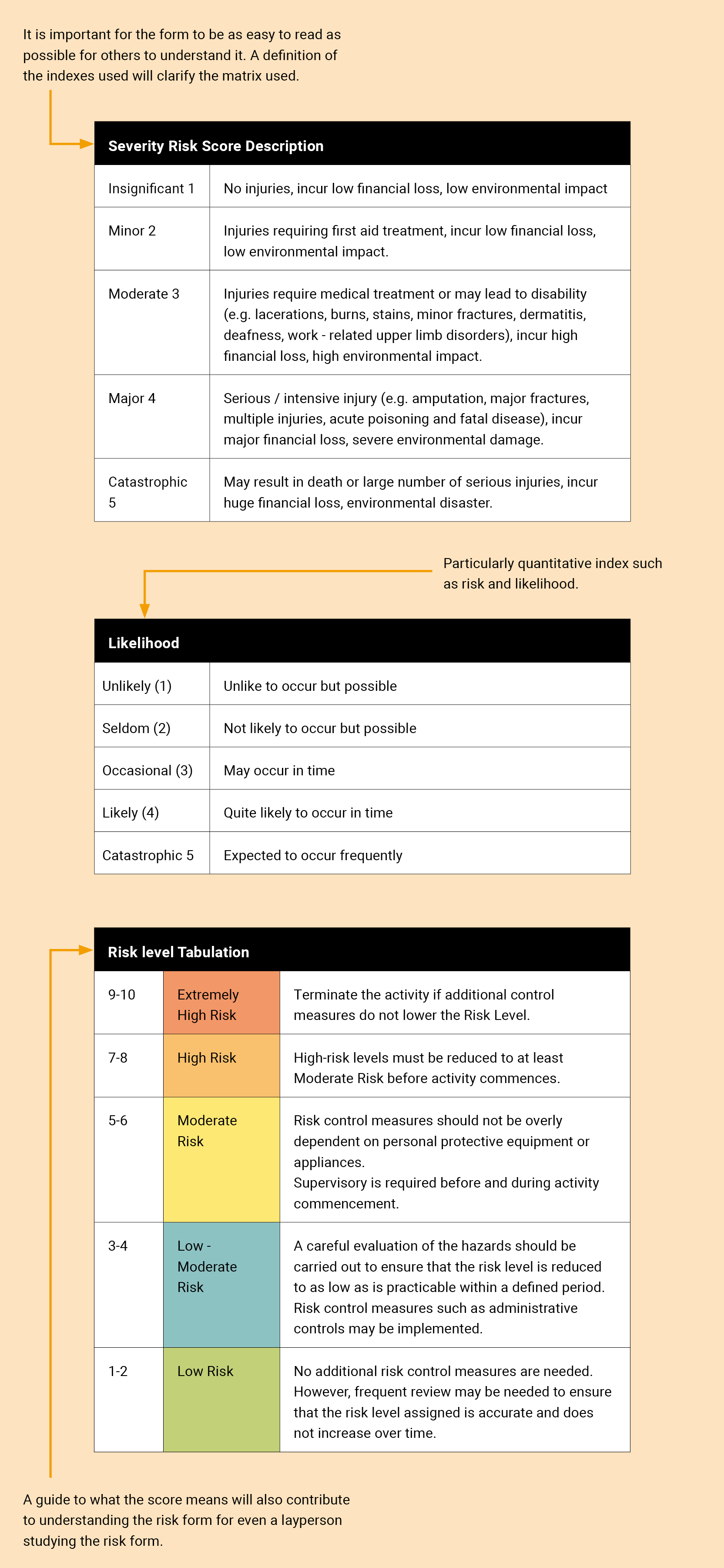

Risk is often an obstacle and an element prevalent in any form of outdoor activity. In risk management, Attarian (2012) identified different types of risk: in ‘risk’, ‘inherent risk’, and ‘perceived risk’. Risk in this context refers to the possible degree of harm or danger that may be encountered during an activity (may not be specific to only outdoor lessons). Inherent risks are risks that are unavoidable as part of the learning activity (e.g. running activity and falling). Perceived risk used here refers to the awareness of the activity conductor in spotting the possibilities and dangers associated with the activity. The challenge with teachers then, is to strike a balance between risk and inherent risk to not compromise any aspects excessively, while being aware enough to spot perceived risk to conduct the activity safely. Taking risk management seriously involves keeping perceived risk high and reducing risk factors via a variety of methods.

Risk and Perceived Risk

Risk, or risk factors, are factors of instances where some form of harm may be present in an activity. As different regions and sources define and work with terms and explanations differently, the chapter refers to ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) as the base reference for ease of discussion. ISO 31000 defined risk in risk management as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives, whether positive or negative” (ISO, 2018; p. 2). In their working definition, Risk is expressed in terms of risk sources, potential events, their consequences and their likelihood. When preparing for a lesson outdoors, teachers need to be conscious of the risk (source and event) and the severity of the risk (consequence). The frequency or likelihood of it occurring is another factor for consideration in the scope of the matter. Where risk factors are controlled by managing source, event, and likelihood, perceived risk engages with the awareness of risk that may otherwise not be prepared for. The ISO statement specifically included the phrasing of uncertainty in their statement to capture the emphasis of preparation and awareness to avoid, as much as possible, the degree of uncertainty in any learning activities. Attarian (2012) specifically noted that risk and risk factors should be lowered where possible but the perceived risk of the teachers should be kept high so as to maintain the reflexivity to assess variables related to changing circumstances that are in the nature of outdoor lessons.

Inherent risk

The context of inherent risk refers to risks that are inherent to specific activities. Any activity comes with its own set of inherent risks that may sometimes be severe and unavoidable. In activities where there are water elements or take place close to water bodies, risk will be present and would be something to plan for. In cases, however, where swim/water literacy is the learning objective, removing the element of water defeats the practical consideration of swim/water literacy. Drawing from Kolb (1984), Harris and Bilton (2018) highlighted the affective benefits of active experimentation even in abstract subjects like history. Where the risk element is part of the learning experience, teachers then have to balance the merit of the activity with the learning objectives. It is important, however, not to mistake complacency with the acceptance of inherent risk. Using the same example of swim/water literacy, risk reduction actions or considerations of the depth of water compared to the learner’s height, a lifeguard being present, or teachers/learner’s ratio are just some considerations that could be set in place that do not affect the learning experience.

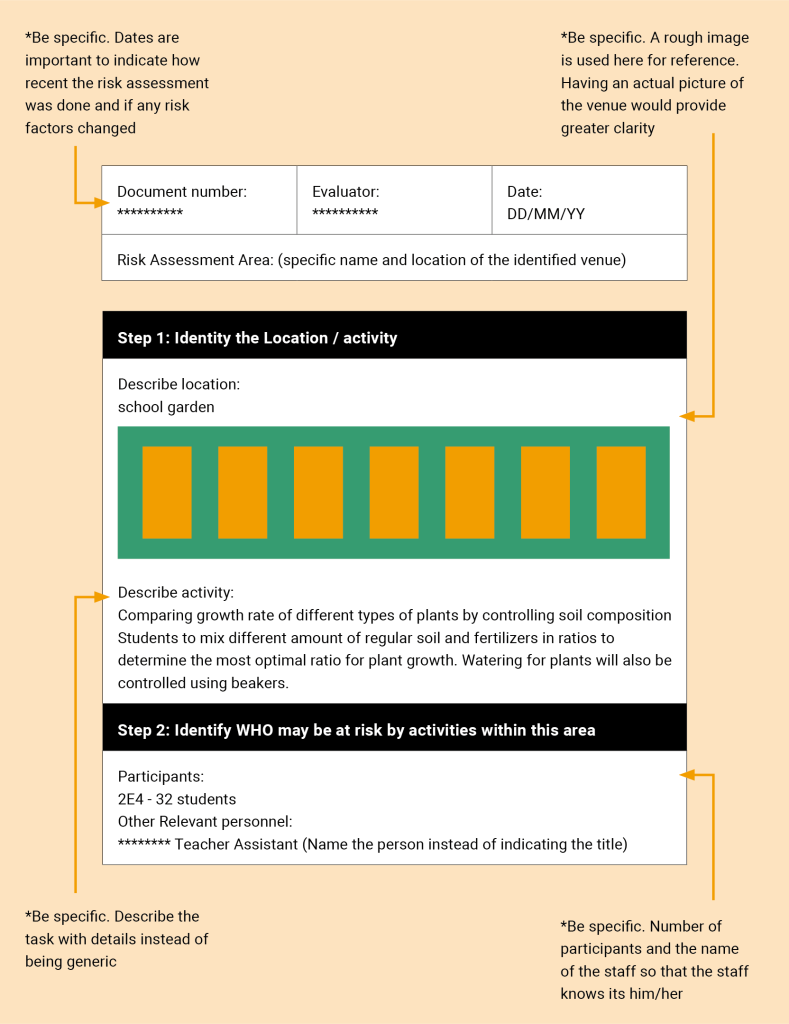

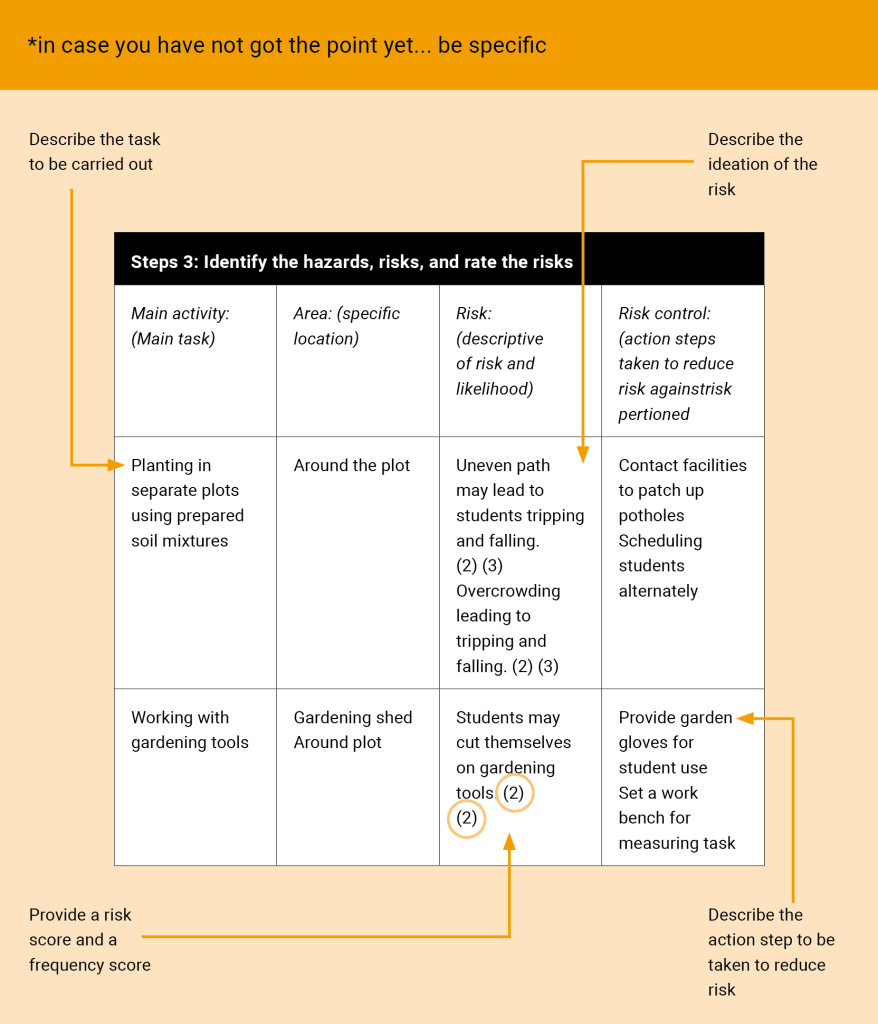

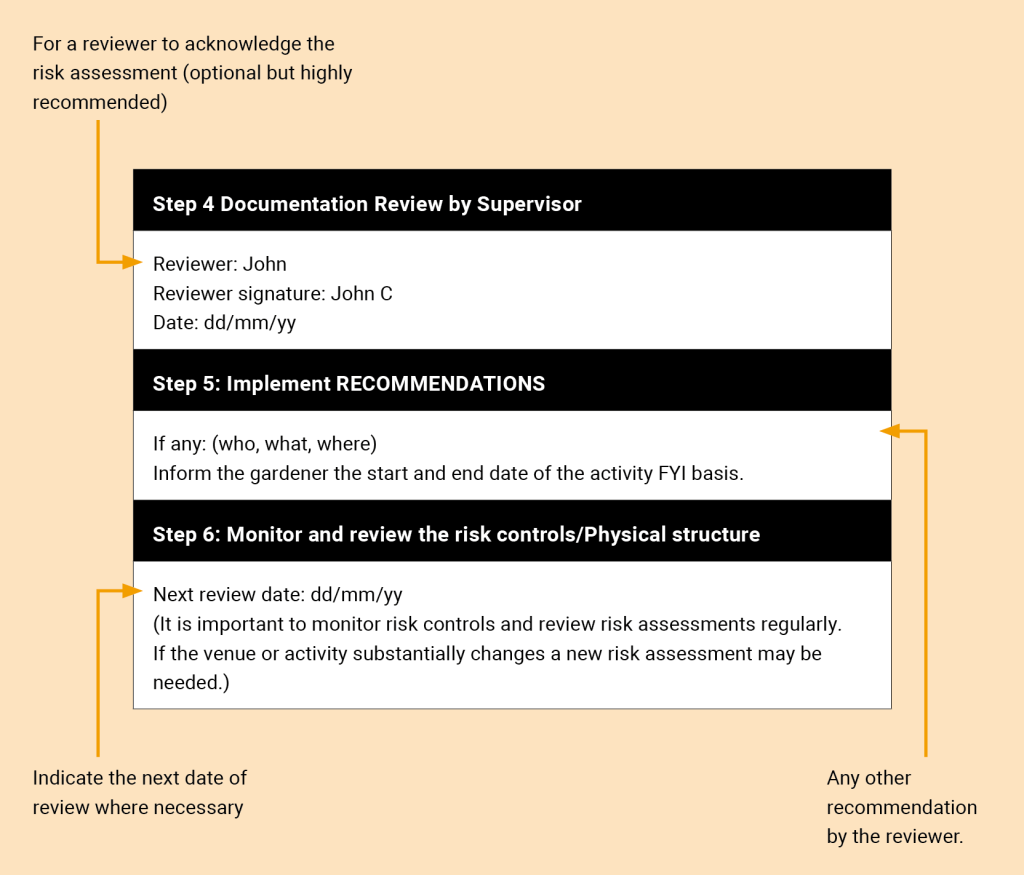

The use of a risk assessment form is often used as documentation to demonstrate the risk assessment, the risk reduction, and the personnel responsible are communicated and set in place. The purpose of the form is an important piece of communication for teachers and anyone involved in the activity to clearly communicate the task, the risk involved, and the individual responsible for supervising the risk. A well-prepared form can also be used for beginning teachers, who might have limited experience with the activity, to identify risks that they might have otherwise not been able to. Due to the nature of activities conducted outdoors, there may be times when an immediate decision needs to be made. At such times, rather than rely on human response, which may vary with emotional and contextual elements, it would be more effective to trigger prepared protocols as indicated on risk forms to ensure safety plans are followed.

Risk Analysis

There are several ways that risk assessment can be conducted. The most common would be through a systematic approach followed by a well-crafted risk form.

Look at the example[1] below that demonstrates how the risk form should contain key addresses and information.

The following risk form was used for a science lesson in a general education school in Singapore. The lesson was crafted for learners to experiment with the growth of cucumbers, watermelon, and lady fingers under different controlled conditions to determine the best conditions for growing these plants.

Learning Objectives include:

- Recognising that the different mixtures of oil and fertilisers have different effects.

- Different types of plants require different conditions to allow for the best conditions.

- Pathway of growth following natural weather conditions (sunlight, rain, plot size).

The risk assessment was carried out systematically, following a pre-designed risk form. There are different ways that risk assessment can be carried out, including even more advanced forms of risk assessment that can include learners in a reflective exercise or co-assessor. Salmon et al. (2014) analysed 1014 leading outdoor activity injuries and near-miss incidents and found that the elements most frequently involved in incidents were hazardous terrain (50.20% of all incidents), participant unsafe acts (29.78%) and teachers’ judgement errors (29.59%). In the activities that they identified, the greatest number of injuries occurred in activities such as Free time (90.3% of all injuries), Ball sports (90.0%), Initiatives (91.1%) and Weapons (100%). The value of educating participants carries with it a level of risk prevention as they were noted as the second largest risk contributors, at the level almost even with instructors. It could also be observed that although Boating accounted for 53.9% of injuries, fatalities were recorded at 4, indicating that low injuries are not necessarily associated with severity. In that sense, responsibility for risk is not just for instructors or designers. It would be noted, however, that participants need to be at a relatively high cognitive level to engage in the activity.

Let us pause and reflect

- How can learners be involved in a risk assessment process?

- What value or perspective can they bring to a risk assessment?

Parent Engagement

Consent

Consent forms are another important preparation that teachers need to prepare to effectively engage important stakeholders, such as parents. We previously discussed the context of risk aversion, which carries with it a whole host of developmental issues for learners in their developmental years to adulthood (Paulsen et al., 2012). Parents are gatekeepers of participation, as they hold the right to withdraw their child’s participation, particularly in the OE context where risk is often associated with. Parents are also important partners in the learning journey of a child, not just gatekeepers. There are two forms of consent: active and passive. Active consent refers to consent that requires permission for participation, while passive consent refers to requiring a signed form for activity omission (Spence et al., 2015). In passive consent, an information sheet would be provided instead of a consent form. Traditionally, passive consent forms tend to have the least effect on participation due to a myriad of reasons (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008; Spence et al., 2015). The context, however, may be subjective to the respective region’s regulation on consent for types and formats of activities due to concerns with passive consent violating the rights of parents who may not have received proper notification (Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008). Consent form formats may vary and are often available widely online. In the context of inclusion and engagement, we would instead focus on the information sheet as an engagement tool to increase participation.

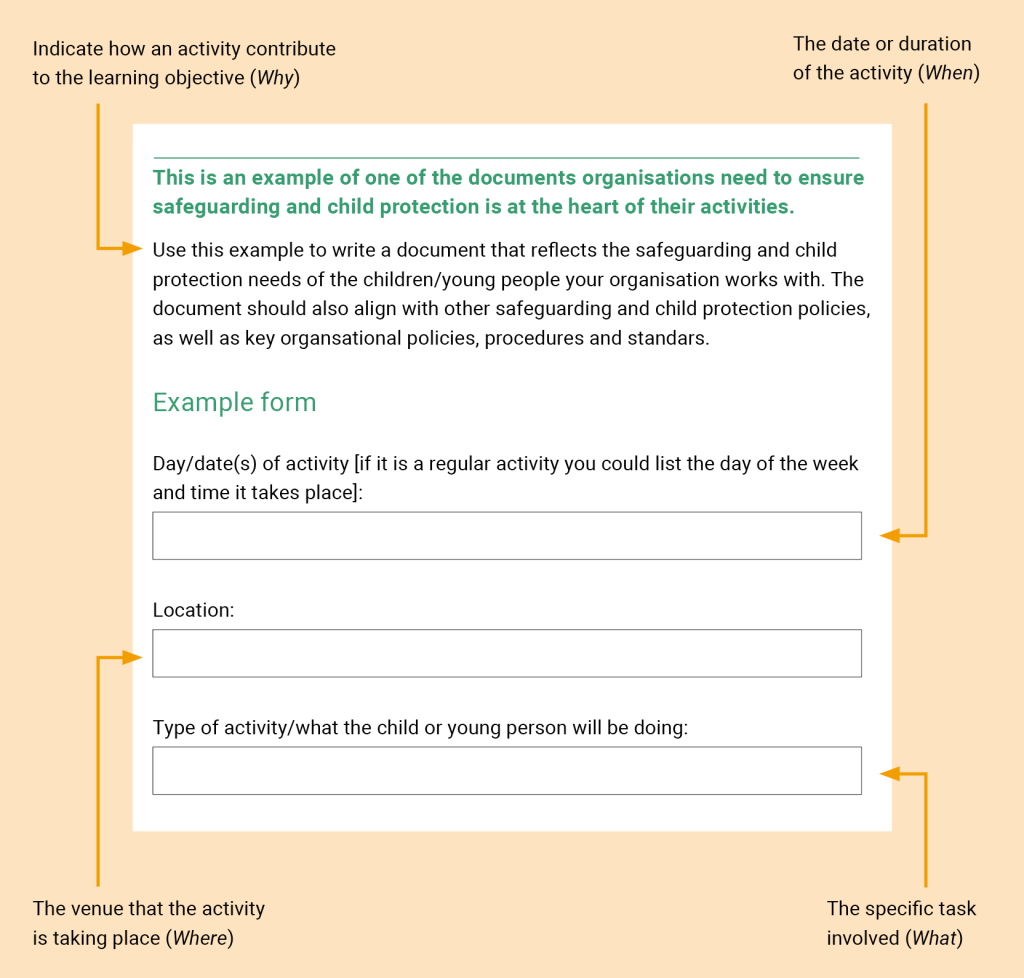

Information Sheet

Research has shown that consent forms contribute little to the active engagement of parents in the learning experience of a child (Fletcher & Hunter, 2003; Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008). Kraft et al. (2020) found that even prior to consent forms, 67% of parents have already decided whether to enrol their child or not. The research was consistent with prior research conducted by Grady et al (2017), where they too identified that parents’ engagement does not change significantly between an elaborated consent form and a short one. Their research highlighted a key point in engaging parents in education, that continuous engagement has more efficacy than relying on consent forms to increase participation. Not omitting the usefulness of information sheets in engaging parents, a well-made information sheet can increase participation, and thus inclusion, by providing information that can inform parents of the value of a learning experience. Particularly when parents may have inhibitions towards outdoor activities, which have often been mis-associated with risk. In a report on Reporting to Parents in Primary School, Hall et al. (2008) found that schools that use newsletters to engage with parents report the highest parent satisfaction. One of the schools within the research employed bi-weekly newsletters where parents reported high confidence and comfort in the school’s approach and interventions (Hall et al., 2008: 99). For an information sheet or newsletter to be effective, there are key elements that must be included. Key elements to include in an information sheet include: Why, When, Where, and What. Participation is the basis of inclusion before any manner of intervention can work. The intention is not simply to inform but to engage parents across a range of different engagement levels to foster participation so that the learning experience can be maximised.

Information sheet example

| Why | Informing parents of the value of the activity and how it contributes to the child’s growth. It is important to indicate how the activity contributes to the child’s growth. |

| When | The date and duration of the activity provide clarity in the event where travel accommodations need to be made. |

| Where | Where the activity is taking place can also inform parents of the array of items that may be associated with the venue. Particularly in the event where parents have to prepare any additional items that are not included in the activity preparation. It is important to note that parents should not be tasked with preparing necessary equipment for the activity to be conducted. |

| What | The specific task that is required of the student. This prepares the parents to be aware of any physical consideration they might feel is necessary to provide to their child. |

Let us pause and reflect

- If you were a parent, would you prefer a consent form or an information sheet?

- If you were a parent, what type of information would you look out for in an information sheet/consent form?

The way we presented OE in the chapter invites readers to approach OE not as a peculiar form of education but as a benefit-driven one. The value of any education approach lies in the benefits that it can bring. OE can be a subject in itself or a natural context that we engage with to maximise learning. Effective preparation in forms of risk management and information sheets can alleviate concerns and resistance that are often falsely associated with OE. As teachers, we all know how difficult it is to make lessons ‘fun’ to keep learners engaged. With OE, we are inversely presented with inherently fun activities that we need to maximise the ‘educational’ aspects. Learning is natural and fun; let us try to keep it that way.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- As a future teacher, what kind of skills and knowledge do you think you may need to be prepared for Outdoor Education?

- Thinking about your context, how would you involve the local community and natural environment in your teaching? Why?

- Think about an example of effective educational use of risk in an outdoor setting. How would you manage it?

- From your standpoint, what are the most important benefits of Outdoor Education in terms of inclusivity?

- How would you make Outdoor Education applicable to learners at all phases?

Literature

- No risk form will be able to cover all considerations and contexts, teachers should adapt and use any tools reflectively to best meet your needs and considerations. ↵