Section 1: Developing Inclusive Educators

Inclusive Education and the Challenge of Mentoring through Dialogue – Reaching out to one another

Ines Boban; Dror Simri; and Linjie Zhang

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Once when Dror was working with teachers who were trying to adopt dialogic mentoring as part of the school’s educational work plan, a 43-year-old teacher asked him: “On what exactly do you expect me to talk to a 13-year-old girl about? What do we have in common besides the lessons? We have nothing in common.” Dror asked her: “Were you once 13 years old? Are you both part of a family? Are you also a daughter? Do you also have relationships with your parents and siblings? Do you both experience fears, hopes, dreams, failures, successes? Are you both human? Dror also added: “Would you have been glad at the age of 13, that someone would be interested in all of these beyond being busy with classes and exams? There was a short silence and then the teacher said, “I never felt seen when I was 13 and for many years after. It caused me much pain and it left deep scars.”

Dror Simri, education counsellor and family and couples therapist, Israel

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is Dialogic Mentoring?

- In which way is Dialogic Mentoring a humanistic existential challenge?

- Why is mentoring important for schools and especially a key-element for inclusive settings?

- How does Dialogic Mentoring work?

- What are the benefits of Dialogic Mentoring?

There are also many more questions, connected to Dialogic Mentoring, that will be uncovered during this chapter.

Introduction to Topic

“Be yourself. No matter what they say” (Sting). When focused on inclusive education Stings words sound so right and obvious, but often they are very hard to fulfil. Especially in parts of a lifetime spent in institutions with rigid policies like many of the educational systems we know. Policies that lead to the phenomenon that teachers are driven to pay more attention to teaching subjects and inflicting discipline than to acknowledging children as whole and unique human beings. A situation that stacks obstacles that makes it hard to realise the inclusive goal.

Children and teenagers are busy in their everyday life with countless existential questions. Questions related to identity, values, morality, meaning. Addressing these questions means acknowledging children as whole human beings. Who addresses these issues in schools today? Who supports the students while they are engaged in the process of building their identity, consolidating values, dealing with moral dilemmas, and defining personal goals? This is where mentoring comes in. It is impossible to think that students can make the most of learning and developmental processes when such essential questions remain unnoticed and unanswered.

The idea that we can teach and educate children without being interested in their unique world, without paying attention to their mental, emotional, and social situation, without paying attention to relations, sounds impossible. At the heart of this chapter is the assumption that paying attention to relations is a critical aspect in achieving educational aims especially when dealing with inclusive education. Making room for attention to relations is the way to focus on our students as whole human beings. We are suggesting that via professional mentoring this absence can be restored.

This chapter deals with mentoring; a term used in many fields but without a clear definition. You might have come across mentors in the education system in many forms. Students who volunteer to be mentors to younger ones in order to support them to settle in and adjust to school. Something like riding a tandem instead of riding the difficult “singles” of the school world alone. Sometimes mentors will be staff members who help students plan careers that are appropriate to the school’s standards and expected by the institution. However, none of these focus on the student as a subject. Would it be nice, as a student, to be in a professional relationship with a staff member who is dedicated to helping you find and define yourself no matter where your dreams, ideas or goals may go? This could be a game changing role for adults in schools that intend to be inclusive places.

We chose to define mentoring as a collaborative relationship that is reciprocal and is aimed at supporting personal development and growth. In the chapter we introduce a mentoring model that follows this definition and was developed in Israel in the Hadera Democratic School (H.D.S.) – called “dialogic mentoring.” Apart from being democratic, the H.D.S. is also inclusive. It has, among its students and staff, those with special educational needs, new immigrants and religious students and teachers Jewish and Muslim. We are introducing Dialogic Mentoring because it is a well-established model and has proven itself. The model was adopted in full or in part in many schools in Israel.

Dialogic Mentoring is a call for change in the relations between teachers and students as a new pedagogical approach. It focuses on relations because of the understanding that relations are the base for any kind of mutual learning process and the base for applying efficient and beneficial support processes. In order to do so, Dialogic Mentoring acknowledges the negative effect on school life and school culture of existing power relations between children and teachers and challenges them. It sees children of all ages as whole human beings and tries to put down the cultural “age barrier” that divides children and grownups. We introduce Dialogic Mentoring as a humanistic existential challenge, a new educational support role and a unique way to put human rights into action.

Key aspects

What is behind Dialogic Mentoring?

Dialogic Mentoring is structured on three levels. It is essential to understand and acknowledge them as a starting point.

● A: Recognition of children as unique whole human beings. That means accepting them as unique, independent, autonomous, sovereign beings that have a rich mental world, have views and understandings about life, have values, commitments, goals, fears, hopes and many unresolved questions.

● B: Dialog as a means of building relations. Dialog in the sense of an interpersonal engagement that encompasses the whole dimensions of human experience. That is driven by curiosity, humbleness and empathy, that acknowledges and accepts the otherness of every person. This involves not seeing the otherness as an obstacle, but rather as an advantage. Doing our best to engage each other with the whole of our being.

● C: The importance of allowing every person to exercise their freedom so they can fulfil and enjoy their full human potential.

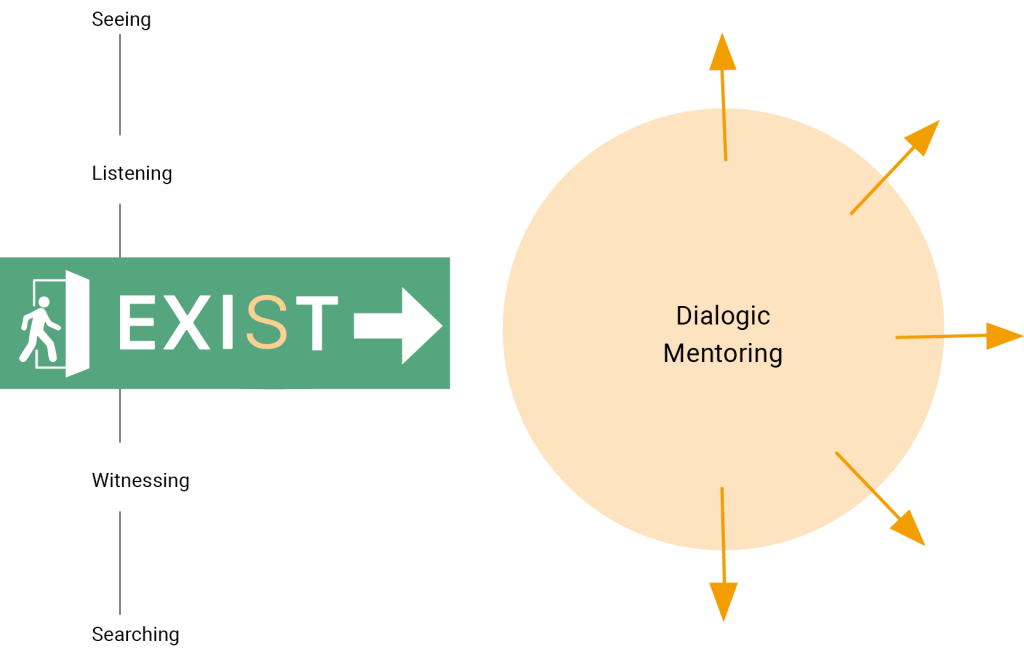

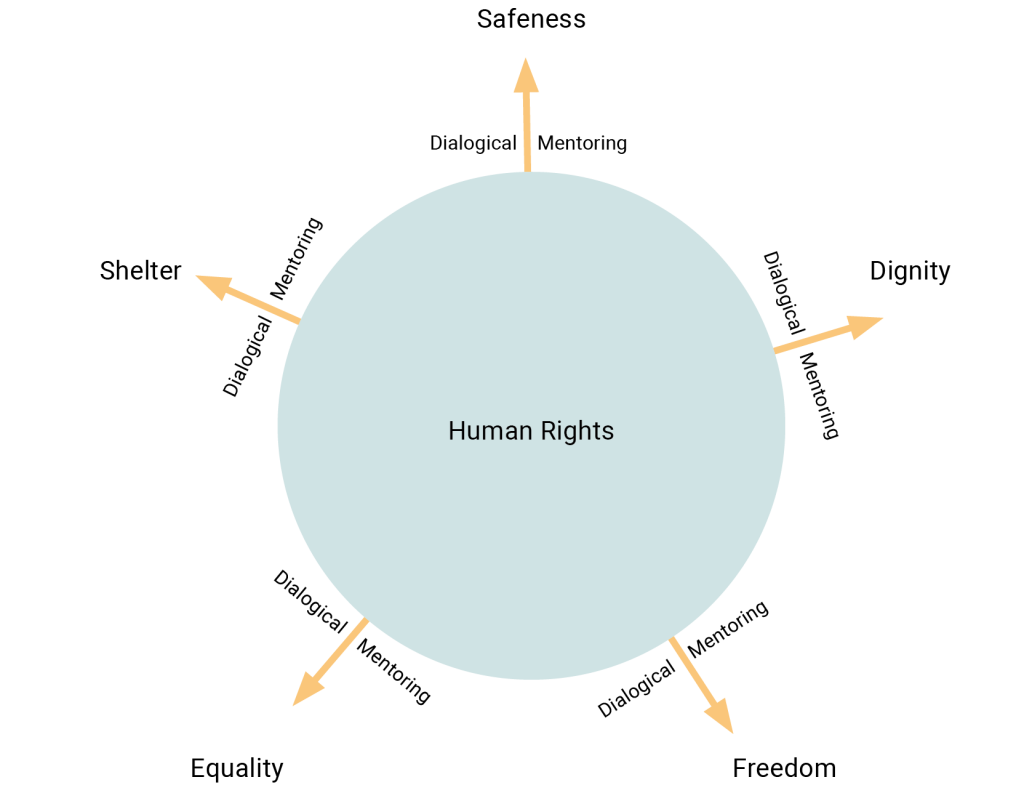

If we take into account, the normative experience of most school lives this ABC of Dialogic Mentoring may seem like a big challenge. Nevertheless, as we go on with the details of the model it’s necessity and its benefits will be clear. Figure 1 below shows that D.M. is at the heart of inclusive education and is part of reaching out to one another.

Dialogic Mentoring – A humanistic existential challenge?

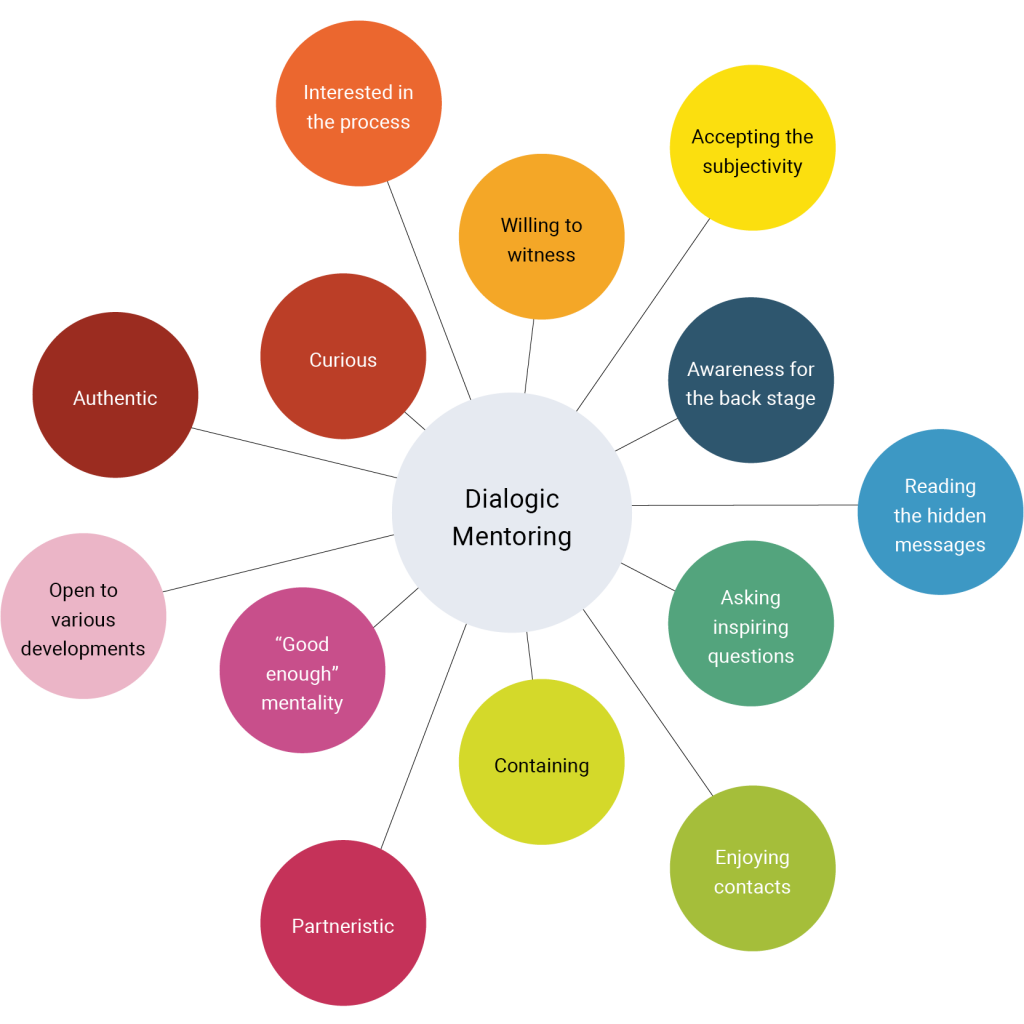

To describe this challenge, imagine these ‘simple’ actions and attitudes in contexts of schools – they make clear what Dialogic Mentoring is about (see also Fig. 2) (Simri, 2020):

● Dialogic Mentoring is about the will to see. To see the people around us. To have the courage to see the whole of their existence.

● Dialogic Mentoring is about the will to hear. Hearing the words and hearing what is behind them, around them, hearing what is not said, but is implicit.

● Dialogic Mentoring is about agreeing to be a witness to what our students feel, experience and do. Witnessing without judgement or criticism.

● Dialogic Mentoring is about wanting, a real deep wanting, to connect to each other. To put into action our natural tendency for affinity, even though we understand that each one of us is different, completely unique and that we will never be able to experience and fully understand their way of seeing, understanding and experiencing the world.

● Dialogic Mentoring is about accepting the complexity of things. Understanding and knowing that behind what we see and hear there is always something more waiting to be seen, to be found, to be heard. Something waiting to be understood, to be recognised.

Figure 1: What Dialogic Mentoring is about (own figure)

Dialogic Mentoring is the understanding that it is our duty as grownups, who made the choice to work with children, to stand up to these challenges and try to see and hear what hides inside the inner world of students. What is hiding there that is important to them, whatever their age may be? Understanding that it is important to the student to be acknowledged and appreciated not only as a student but as a whole human being. Understanding that each person has a gift to give the world, but it will only be given if we make the effort to find it, if we assure them, they are safe.

This is why our curriculum, at least part of it, even a small part of it, should be dedicated to making the effort to find out what is there that our students want us to see, want us to hear. We should remember that what is hidden in their inner world is not all about pain, confusion and sorrow; it is also about new ideas, creations, special and unique points of view. It holds information, wonders, and knowledge that are important to be recognised not only for the benefit of the student but also for the benefit of all.

When we concentrate on seeing and hearing each other as whole human beings, as subjects that hold information that are very important to be heard, what usually emerges are acceptance, closeness, empathy, altruism and love. This is the important piece, the magic of dialogic mentoring.

When this kind of relationship exists, normally creativity appears, the ability to learn new things, find new interests and a greater understanding. We feel seen and safe. We build confidence in the possibility to shape our reality. We find that we can clearly determine what is important for us, and we find it is easier to achieve. In this state of being we most commonly feel moments of joy, connection and a deep and meaningful feeling of existence.

The main tool that enables us to achieve such relations is the dialog as it is presented in the philosophy of Martin Buber. In his view, dialog is understood as a space of existence formed by the relations between the “I” and the world around it. From this point of view the “I” does not exist as a separate entity. His existence is the outcome of the affiliation between him and what surrounds him. The way we perceive and relate to whatever is around us defines our state of being. It will determine what kind of “I” will be present at that moment. An “I” that encompasses our whole being or just a part of it.

If we relate to a person in front of us in a superficial way, the “I” that we shall experience at that moment will also be a partial and superficial one. On the other hand, if we relate to it as a whole human being, the “I” we will experience will be a whole one. For example, if a teacher is trying to teach a young student addition, the teacher will see her/him just to that extent – a young student to teach addition to. The teacher will perceive the student in a shallow way and be partially aware of her/his whole existence as noted above. In this case the teacher will also experience herself/himself in a very shallow way. She/he will experience her/his being partially – she/he reduces her/his being only to a teacher that wants to teach a student addition. However, if she/he perceives the student as a whole human being, she/he will pay attention to how she/he behaves and reacts. She/he will pay attention to her/his words, expressions, and body language. She/he will really care about what is going on inside her/him. What are her/his thoughts? Is she/he happy? Is she/he afraid? Is she/he open to learning or bothered about something? If she/he will remember that she/he is a unique miracle of nature – one of her/his kind, she/he will experience the student for the whole of her/his existence and so she/he will experience her/his own whole being. All of her/his mental, emotional, physical abilities will awaken and be present.

When this happens a very special experience of existence appears. An experience that brings forth what was described above. This is the experience we are looking for when we talk about Dialogic Mentoring. This state of being is not easy to achieve and is hard to maintain for a long time. In order to create it we have to make an effort. We need to be focused on remembering our aim and to be aware of our mental and emotional state during the interaction. When we succeed in creating and maintaining these moments, they will yield what was described above.

If in our school, all through the day, all the mentors and teachers aspire to create such moments the whole school becomes a dialogic sphere. It will become a space of existence that will allow deep listening, an experience of connection and an awakening of creativity, involvement, and responsibility.

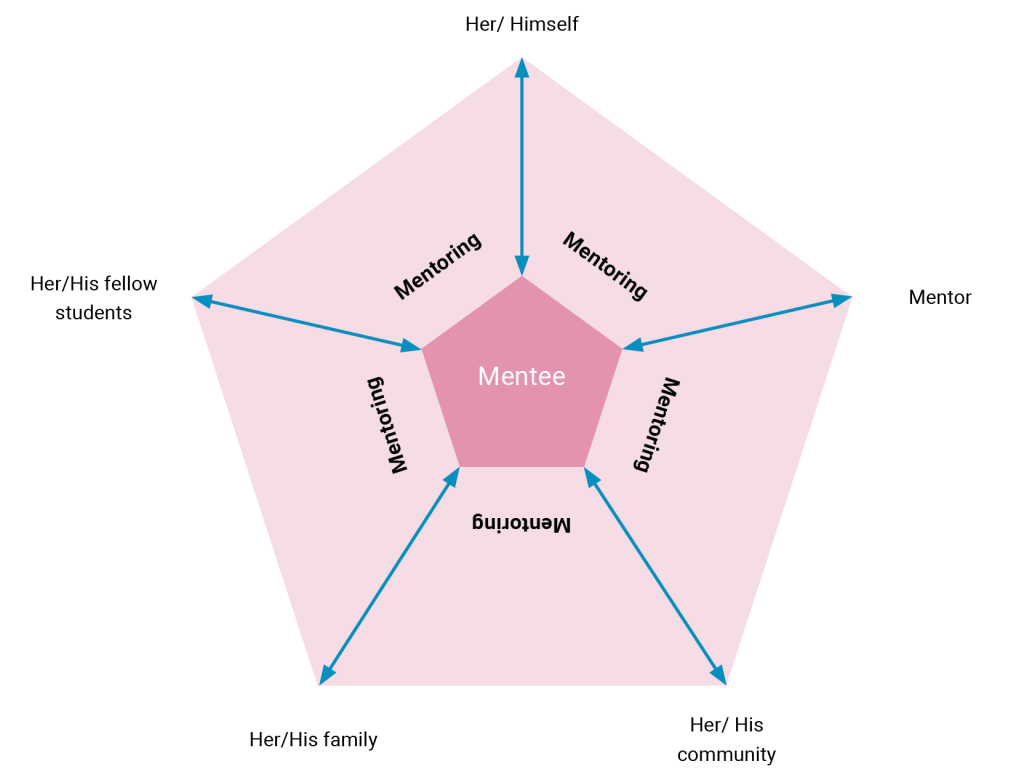

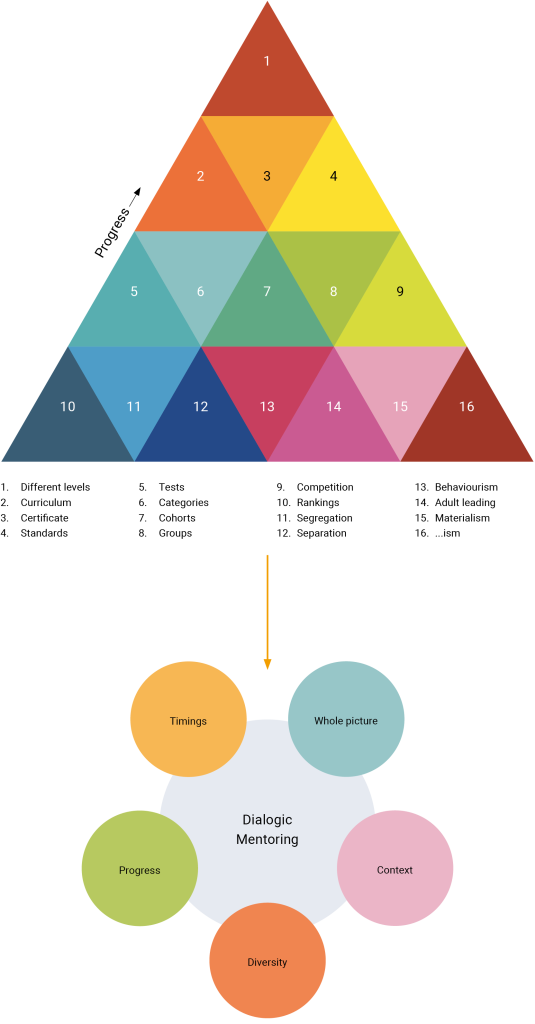

Figure 2: What influences a mentee? (own figure)

What does this new educational support role look like?

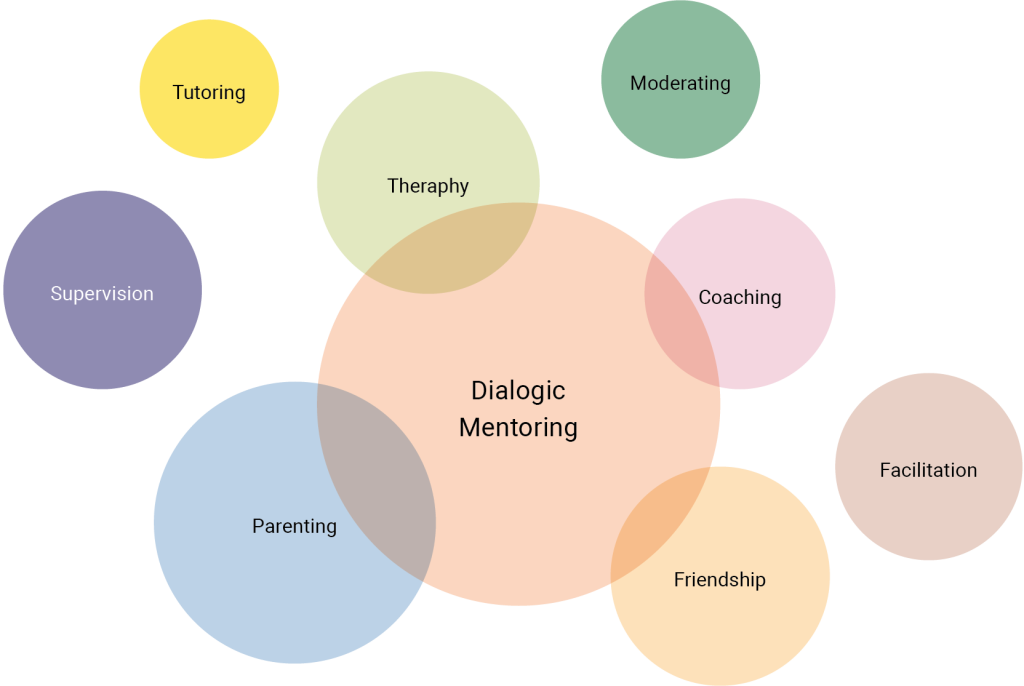

Dialogic Mentoring compiled parts of existing support roles and put them together to form a new educational support role that is based on the three principles ABC described above.

The mentor creates for the mentee and herself/himself an intimate and safe space. She/he is there to help in any situation. These components are found in parenthood and friendship. The mentor creates relations based on equality and mutuality like in a friendship. She/he has experience and maturity like their parents. She/he acts from an empathic standpoint, uses mentalisation, and frequently reflects like therapists would do. She/he supports self-realisation and inner growth processes, goal setting and finding a way to fulfil them – in a way therapists and coaches do.

However a Dialogic Mentor is not the parent of the mentee, or a friend. She/he is not a therapist or a coach. She/he does not hold the responsibility of parents and does not substitute them. She/he is not entangled emotionally with the mentee like very often family relations are. She/he is not in competition with the mentee like friends often are and she/he does not take part in the mentees adventures of growing up. She/he does not diagnose the mentee, or meet her/him in a strict setting detached from life, but is a witness helping the mentee reflect and act in everyday life. A Dialogic Mentor helps the mentee determine their own goals and acquire tools to fulfil them – and she/he concentrates on the process and not the potential results as Figure 3 clusters:

Figure 3: Aspects of Dialogic Mentoring (own figure)

How is Dialogic Mentoring connected to Human Rights?

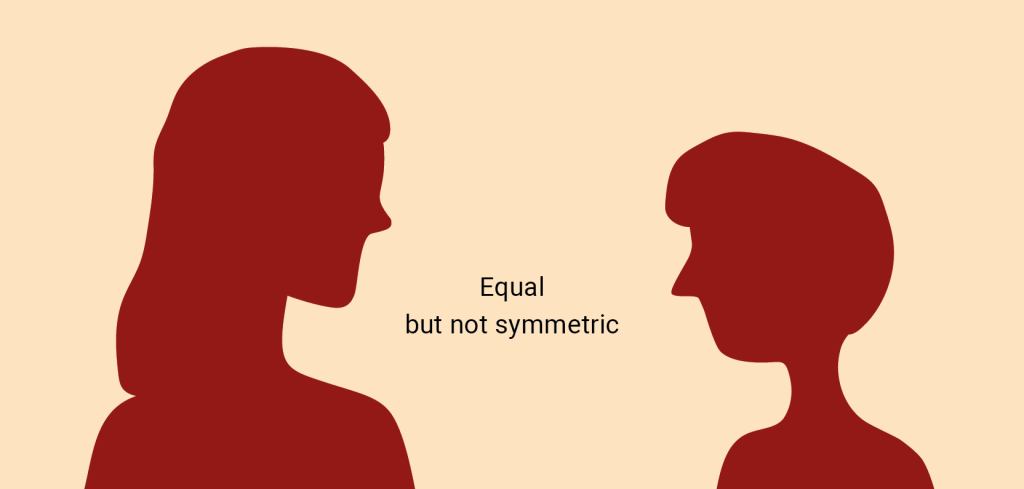

When the relations between all that attend school are open and equal (but not symmetric), when personal freedom is guarded, when everybody is acknowledged and can feel safe, dignity is being realised to its full extent and human rights are put into action.

Human rights, constantly evolving, serve has been an enduring guiding principle. From time to time, this statement is specifically updated and made more concrete by various agreements and treaties, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990).The goals of Dialogic Mentoring are shaped by the children’s rights framework.

Why is Dialogic Mentoring important for a democratic transformation of schools?

Most societies are following a pyramidal logic as if there were always levels to reach, higher steps to long for and linear climbing to get somewhere in a top position. Riane Eisler (Eisler, 2015, 2017; Eisler & Fry, 2019) calls this the ideology of a “domination culture.” Figure 5 presents this logic on the left side and shows some elements it consists off – all serving structural violence:

Figure 5: The transforming shape of Dialogic Mentoring from pyramids to circles (own figure)

Constructing different levels and certificates as if everyone has to follow a ‘holy’ curriculum and fulfil certain standardised efforts to climb up and reach high levels by overcoming tests by being categorised and compared to a set-up cohort. To set up groups is seen as reducing the complexity and helps to define a frame for competition, so rankings can be used for segregation and separation. To keep this system working, it needs judgements, including rewards and awards. In the tradition of ‘old authority’ (Omer, 2016) they use not only tokens and punishments but all kinds of ‘motivating’ stories to challenge children and focus their will towards materialistic success. One daily materialistic story told while pushing through the pyramid says, ‘Time is money!’ All kinds of ‘…isms’ (adultism, fascism, sexism, racism, …) are nurtured by this up-climbing vision. Here teachers are valued for having their class in their grip … and push or pull their students to the highest level reachable in this certificate dominated logic – to reach their full ‘human capital’, this is also used later for the labour market. As all societies are patterned on a dominator model, in which human hierarchies are ultimately backed up by force or the threat of force. We see that spaces of education and how they are structured and filled play an essential role.

In a hierarchical context ‘mentoring’ will always be a tool to optimise human resources but never Dialogic Mentoring. In a structure like this ‘inclusion’ is just a term that must be added without disturbing the dominant patterns.

What if the story is changed in “Time is life; life is time” (Korten, 2015; 83)? What if there is no pyramid to climb to the top by being ‘excellent’ and leave all other competitors as ‘mediocre’ or ‘weak’ ones behind? What if the narrative of progress in the domination model with fear and suppression is replaced by a partnership model with empathy and respect (Eisler, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2015, 2017)?

Instead of simplifying the educational process by cutting off the complexity, it’s important to see the beauty of being different and equal like Dialogic Mentoring does.

To really practise an inclusive life in schools Dialogic Mentoring would be the core element to find transformation steps towards a common philosophy as shown on the right side of Figure 5: If all agree that there is no pyramid to fit into but we can all stay on the ground in different fields. This is displayed in Figure 5 above as the round circles.

Students labelled as having special educational needs confront many challenges apart from their academic duties. This can harm the studying process and hurt their achievements and development academically, socially, mentally and emotionally.

Thus, it is very important to find an opportunity for them to receive support and assistance so they will be relieved and encouraged. Dialogic Mentoring enables us to deal with that. In order to make that happen, Dialogic Mentoring in education has to widen the scope of subjects brought to the mentoring relations.

Commonly, we talk with our students about their formal learning issues, their grades, and their behaviour in class and school. However, they have a full life that many times is more challenging, interesting and intensive than school. The mentoring process will benefit if it is possible for the mentee to bring his whole self into the mentoring.

As stated before, children have a rich mental world. Very often, they experience pain, confusion and emotions they do not completely understand. All of these influence their everyday life and there is no way of supporting them without bringing them into consideration. Society delivers the message that achievements in school are important, so what happens when a student is challenged by everyday life in a way that disturbs his schooling. How does it influence him? Who is there to assist him aside from his peers? That task can be dealt with by mentoring. So let us decide to change the story (Korten, 2015) and move away from the norms that led to hurt and crisis to a story that carries into a welcoming future. According to David Korten (2023): “Humans are Earth’s ultimate choice-making species. Our decisions have defining consequences for the whole of Earth’s community of life.”

His description of the necessity of awareness about the stories we use underlines what Riane Eisler analyses as serving either a domination system or heading for a partnerist context – and it connects with all intentions to decolonise education. So, there is no doubt where Dialogic Mentoring belongs when David Korten (2023) writes under the chapter title “Sharing an Authentic Narrative”:

“We fail to recognise the tyranny for what it is because we live in a trance state induced by a Sacred Money and Markets cultural narrative that shapes our collective understanding of our world and our choices as a species. It is based on two foundational assumptions:

1. Because we humans are by nature self-centred, materialistic, and inherently competitive, the wealth of the society is best maximised by channelling these natural instincts to beneficial ends through unrestrained market competition.

2. There is no limit to the total wealth of a society. The affluence of the winners is their just reward for their contribution to the well-being of all. If the needs of some are not being met, simply accelerate growth to bring up the bottom.

Both assumptions are critically flawed. An authentic narrative is emerging grounded in three truths essential to our time:

1. As living beings, we are by nature dependent on our ability to organise as healthy communities that create and maintain the conditions essential to our well-being.

2. We humans shape our behaviour by cultural and institutional choices. These can support individualism, gluttony, violence, and competition. They can support communitarianism, frugality, peace, and cooperation. And almost everything in between.

3. We depend on the generative capacity of a finite living Earth and must learn to meet our needs within these limits. Wealth distribution is an essential concern.

For thousands of years the institutions of Imperial Civilisation pit us one against another in a competition for the positions of privilege that favour the few at the expense of the many. The dominator hierarchy of corporate rule and its legitimating cultural narrative are extensions of Imperial Civilisation and the sociopathic behaviour the Sacred Money and Markets story would have us believe defines our inherent nature.”

How is Dialogic Mentoring connected to Inclusive Education?

So, Dialogic Mentoring can become a heart element of finding more inclusive steps to change the rules of ‘the games’ people play and to reorganise procedures, policies, rituals and structures. If the individuals and their topics are heard and become stronger within their settings the groups, communities – any WE – become stronger too. If, as Marsha Forest (O’Brien & Forest, 1989: 3) once said, the only prerequisite for inclusion is “breathing, life itself” – if necessary with a respirator -, Dialogic Mentoring is a condition to a free breath: THE ultimate basis for learning – and living – anyhow.

Similarly, when Jean Liedloff (1986) shows with her “continuum concept” and the “search of happiness lost,” that it is the main longing of every person to feel welcomed, worthy and ‘right’ then it is a way to look at the purpose of inclusion:

● Feeling to be welcomed

● worthy and

● in the right moment at the right place.

Obviously Dialogic Mentoring opens up the space for the awareness of this longing and to express it in a sheltered constellation (the matrix), and then to define steps (the patterns) to create more fulfilling situations. Inclusive education starts with this attitude – it is the basis for following decisions. In a way one could call it ‘inclusive diagnostic.’ If beliefs are formed in a child’s mind by the words of the people who live their daily life with, especially those expressed as absolute truths rather than as opinions, while repetition aggravates the effect, Dialogic Mentoring offers consciousness about these processes and helps to relieve from wrongness to welcome feelings.

To find a common clearness about the matrix first and then agree about patterns on this ground can also be seen in initiating future planning in circles of support.

To deepen and underline Jean Liedloff’s point of view here follows a longer quote as a source for persons involved in Dialogic Mentoring and in that sense inclusive processes of uncovering damaging beliefs, something she calls “our western malady” (1991, 2023):

“I noticed something curious about normal, neurotic adults: what we were experiencing was not a variety of ‘problems’ at all, but rather the very same difficulty. Although the details and degrees of damage differed, the malady was the same. It manifested as a deep sense of being wrong — of being not good enough, not lovable, disappointing, incompetent, insignificant, undeserving, inadequate, evil, bad, or in some other way not ‘right’. What’s more, this feeling of wrongness had come about almost always through early interactions with parental authority figures. And it had evoked powerful unconscious beliefs that have informed our views of both self and self-in-relation-to-others.

Upon coming to this realisation, I searched for words to describe how human beings would have to feel about themselves in order to live optimally, to feel at home in their own skins and represent themselves accurately to others. I thought of the Yequana people, and arrived at the words worthy and welcome. People need to feel worthy and welcome, not bent out of shape, angry, or apologetic about their existence” (Liedloff, 1991; 2023).

Who is involved in Dialogic Mentoring?

The mentoring process involves two main entities: the mentor and the mentee. Each of these participants plays a distinct and crucial role in the mentoring relationship and processes.

What is the role of the mentee?

The concept of a “mentee” can be understood through the lens of personal growth, guidance, and the interplay of knowledge between individuals. A mentee is someone who seeks to learn and develop themselves under the guidance and support of a mentor. The mentee is never identified with the problem that challenges them. As Michael White stated in his well-known quote: “The person is not the problem, the problem is the problem.”

The role of the mentee is not one of passivity but rather an active engagement with the mentor’s facilitation. The mentee is a whole human being holding points of view, having values and knowledge, having plans and goals, and enjoying their dignity. Mentee is the most authorised expert about themselves, who is encouraged to reflect, question, and internalise the lessons imparted by the mentor. Through this process, the mentee is not merely acquiring knowledge but also undergoing a transformative journey, honing their character, and developing a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them.

In some philosophical traditions, the relationship between the mentor and the mentee can be seen as symbiosis, where both parties benefit from the exchange of knowledge and experience. The mentor gains satisfaction and fulfilment from passing on their wisdom, while the mentee gains valuable insights and growth opportunities.

Overall, the concept of a mentee is rooted in the recognition of the inherent interconnectedness between individuals and the belief in the potential for personal and intellectual development through learning from others.

Figure 6: The Relationship of mentee and mentor in Dialogic Mentoring (own figure)

What role is the part of the Dialogic Mentor?

Mentor is a concept deeply rooted in ancient Greek literature and mythology, specifically in Homer’s epic poem, “The Odyssey”. In this work, Mentor is portrayed as a wise and trusted advisor and friend to Odysseus, the protagonist. However, it is essential to recognise that the concept of Mentor has transcended its initial literary context and has become a symbol of guidance, wisdom, and mentorship in broader philosophical discussions (Slatkin, 2005).

A mentor embodies the archetype of a knowledgeable and experienced individual who imparts valuable insights and teachings to a less-experienced person, known as a mentee. The role of a Mentor extends beyond simple instruction; it involves nurturing the mentee’s personal and intellectual growth, providing support, and assisting them in navigating life’s challenges. This relationship is often characterised by mutual respect, trust, and empathy – the Dialogic Mentoring mentioned above.

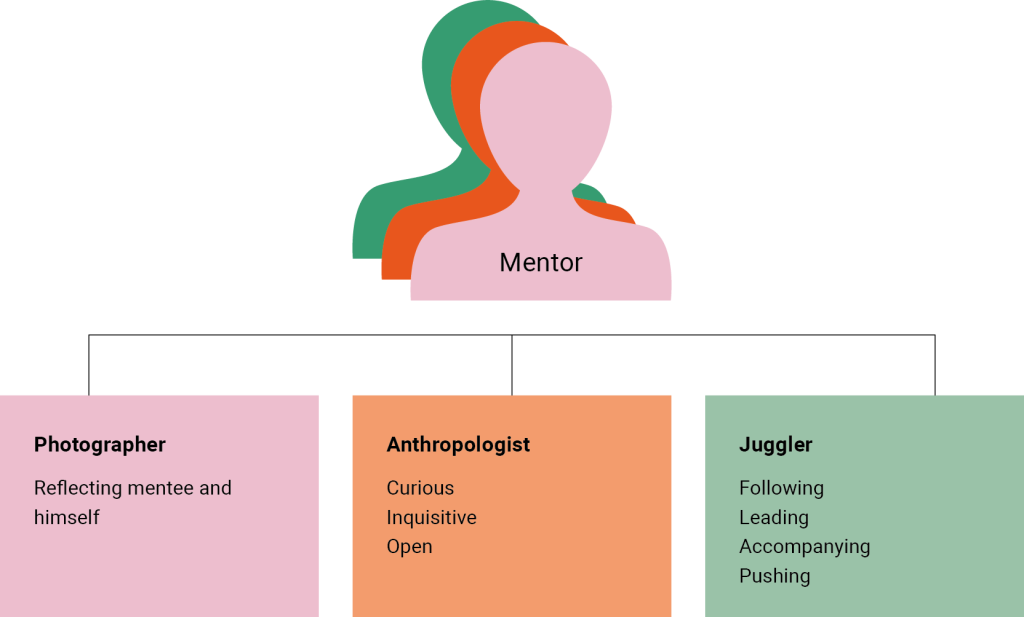

Figure 7: Roles of a Dialogic Mentor (own figure)

If metaphors are used to describe the multiple identities of mentors, then mentors can be likened to anthropologists, photographers, and jungle explorers. The anthropologist embodies an insatiable thirst for knowledge, an unyielding curiosity, and an open-mindedness that propels them to explore the intricacies of diverse cultures and societies. The photographer, in turn, assumes the role of both a reflective mentee and a self-aware artist, skilfully capturing moments that hold a mirror to both the subject and the photographer’s own inner world. Jungle explorer, adept at seamlessly transitioning between roles, alternating between being a companion, a follower, a trailblazer, and an inspirer.

The concept of Mentorship highlights the interconnectivity of human experience and emphasises the value of passing knowledge from one generation to another. The Mentor’s role is not to dictate or impose beliefs but to encourage critical thinking, self-reflection, and individual growth. This aspect aligns with broader philosophical ideas on education, personal development, and the pursuit of wisdom.

In conclusion, Mentor is a philosophical representation of a wise and guiding figure who fosters learning, growth, and self-discovery in the mentee. It symbolises the transformative power of mentorship, wherein knowledge and wisdom are transmitted, contributing to the continuous evolution of individuals and society as a whole (Daloz, 2012; Allen & Eby, 2007).

What qualities does a person need for Dialogic Mentoring?

Dialogic Mentoring requires several key qualities in a Mentor to be effective in the process. These qualities include (Fig. 8):

Figure 8: Attributes for Dialogic Mentoring (own figure, adopted from this project)

- Interest in the process: A person engaged in Dialogic Mentoring has a genuine interest in the process itself, valuing the exploration and exchange of ideas with the mentee. This curiosity fosters an open and dynamic learning environment.

- Willing to witness: The mentor should be willing to listen actively and be fully present during the dialogues with the mentee. Being a witness means being attentive and supportive, allowing the mentee to express themselves freely.

- Accepting subjectivity: Dialogic Mentoring acknowledges that different perspectives and experiences shape individuals’ understanding of the world. The mentor must be open to accepting the subjective viewpoints of the mentee and avoid imposing their own beliefs or biases.

- Awareness of the backstage: This quality refers to recognising the personal and emotional aspects that might influence the mentee’s thoughts and actions. Understanding what happens “behind the scenes” helps the mentor provide more empathetic and insightful guidance.

- Reading the hidden message: Dialogic Mentoring goes beyond surface-level discussions. The mentor should be skilled at understanding underlying messages, unspoken emotions, and non-verbal cues to gain a deeper understanding of the mentee’s needs.

- Asking inspiring questions: A mentor must possess the ability to ask thought-provoking and inspiring questions that encourage the mentee to reflect, explore new ideas, and develop their critical thinking skills.

- Enjoying contacts: Being able to establish a positive and meaningful connection with the mentee is crucial. Enjoying interpersonal interactions and being approachable can create a comfortable and trusting atmosphere for open dialogue.

- Containing: The mentor should be emotionally mature and capable of holding space for the mentee’s emotional expression without being overwhelmed by it. Providing a safe and non-judgmental environment helps the mentee feel supported and heard.

- Partneristic: Dialogic Mentoring is a collaborative partnership between the mentor and mentee. The mentor should view the mentee as a partner in the learning journey, rather than adopting a hierarchical approach.

- ‘Good enough’ mentality: Recognising that perfection is not the goal, the mentor should embrace the idea of being ‘good enough’ and focus on progress and growth rather than expecting flawless outcomes.

- Open to various developments: The mentor should be flexible and open-minded, willing to explore different paths and adapt their approach based on the mentee’s unique needs and learning style.

- Authenticity: Being genuine and transparent is crucial in building trust and rapport with the mentee. An authentic mentor creates a safe space for open and honest conversations.

- Curiosity: Curiosity drives continuous learning and encourages the mentor to stay receptive to new ideas, experiences, and perspectives. It also helps the mentor maintain a growth mindset and model a commitment to learning for the mentee.

In summary, this part introduced some key qualities that could help mentors to achieve Dialogic Mentoring, which requires a mentor who is genuinely interested in the process, empathetic, non-judgmental, open to diverse perspectives, and committed to creating a collaborative and inspiring learning environment for the mentee. This leads to the question: How to develop and improve Dialogic Mentoring?

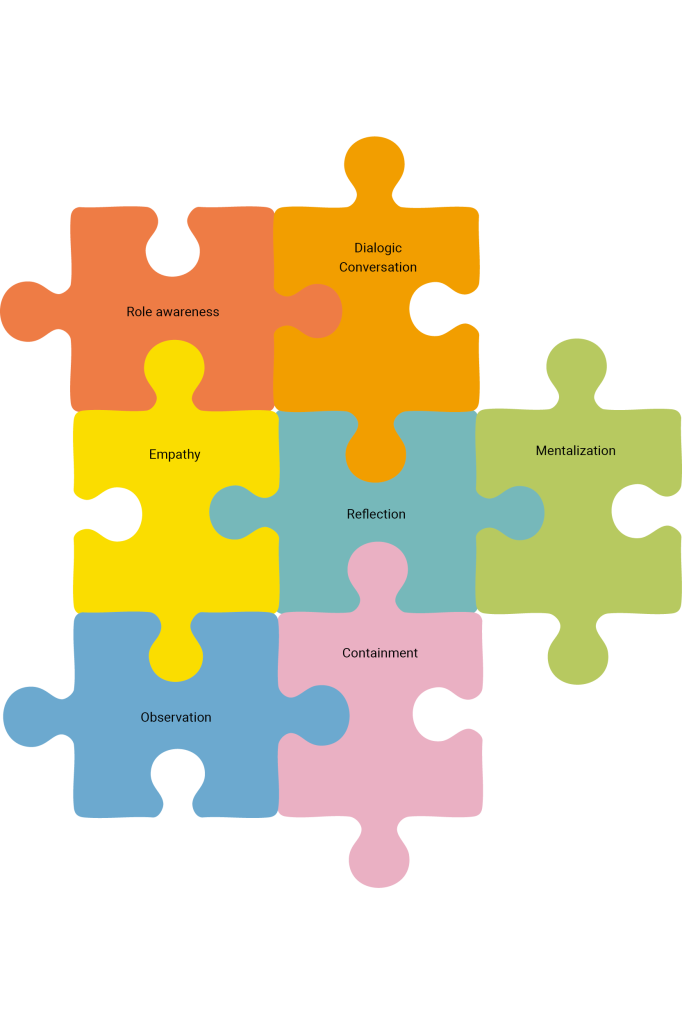

Which attitudes belong to Dialogic Mentoring?

The competences of clear role awareness, partnerism in a dialogic conversation with empathy, willing to reflect, differentiate, and to practise mentalisation, observation and containment, as Figure 9 puzzles together – with space for more:

Figure 9: Attitudes in Dialogic Mentoring (own figure)

Connected to all pieces of the puzzle, there is the importance of an attitude that sees the relevance of a balance between the presence and the future. Does the future already exist? Is it like a train station waiting for us down the line? Is this where we are heading and there is nothing to do but prepare for what we think we saw? Or is it an uncertainty which is formulating in the present? If the first is correct, we have to stretch our necks as high as possible to try to see the next station so we can prepare for it. If the second option is correct, maybe we should be concerned with the present, with our relations today, with evoking our responsibility and understanding how we wish to shape our existence today and not the future.

What do children need us for? Do they need us to install ‘programs’ in them that will enable them to function or are all the ‘programs’ already there and all they need us for is to enable them to run and develop freely?

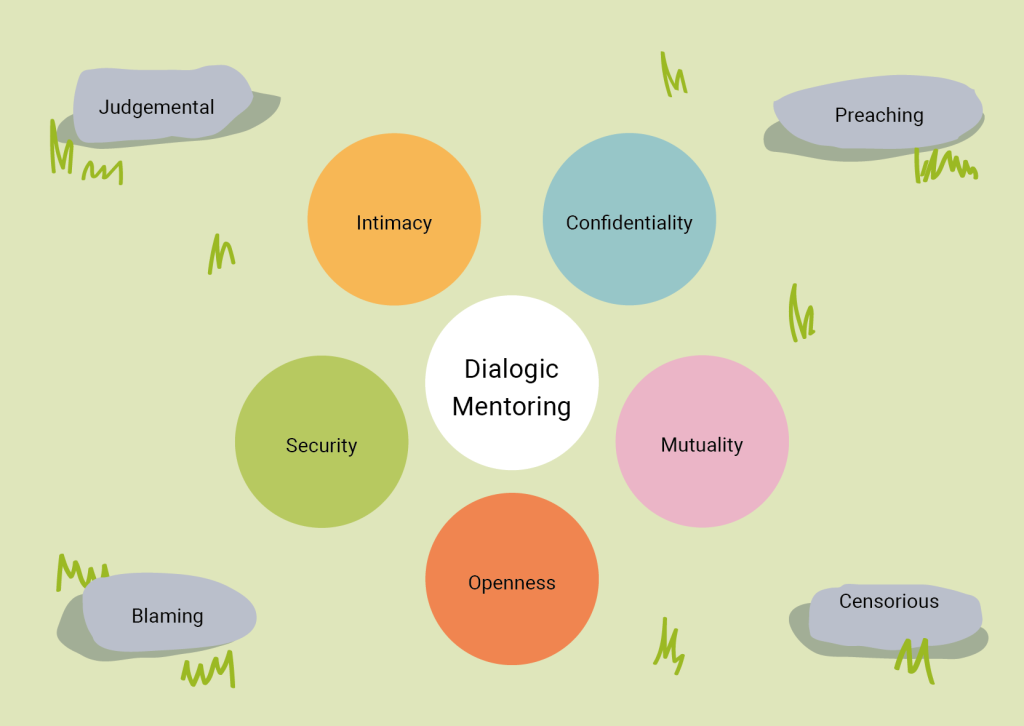

If we accept the uncertainty of the future and accept that our children have all the programs already installed, then the understanding of concentrating on the presence arises … always also aware of the stones that lay on the way (see Fig. 10):

Figure 10: What Dialogic Mentoring can let grow in its presence (own figure)

If we no longer ‘prepare’ for an uncertain ‘futurum II’ (perfect future) by preaching, censoring, blaming, judging, ‘encouraging and challenging’ – openness, security, intimacy, confidence and mutuality can grow; and these are the plants for a bunch of learning everyone needs – right NOW!

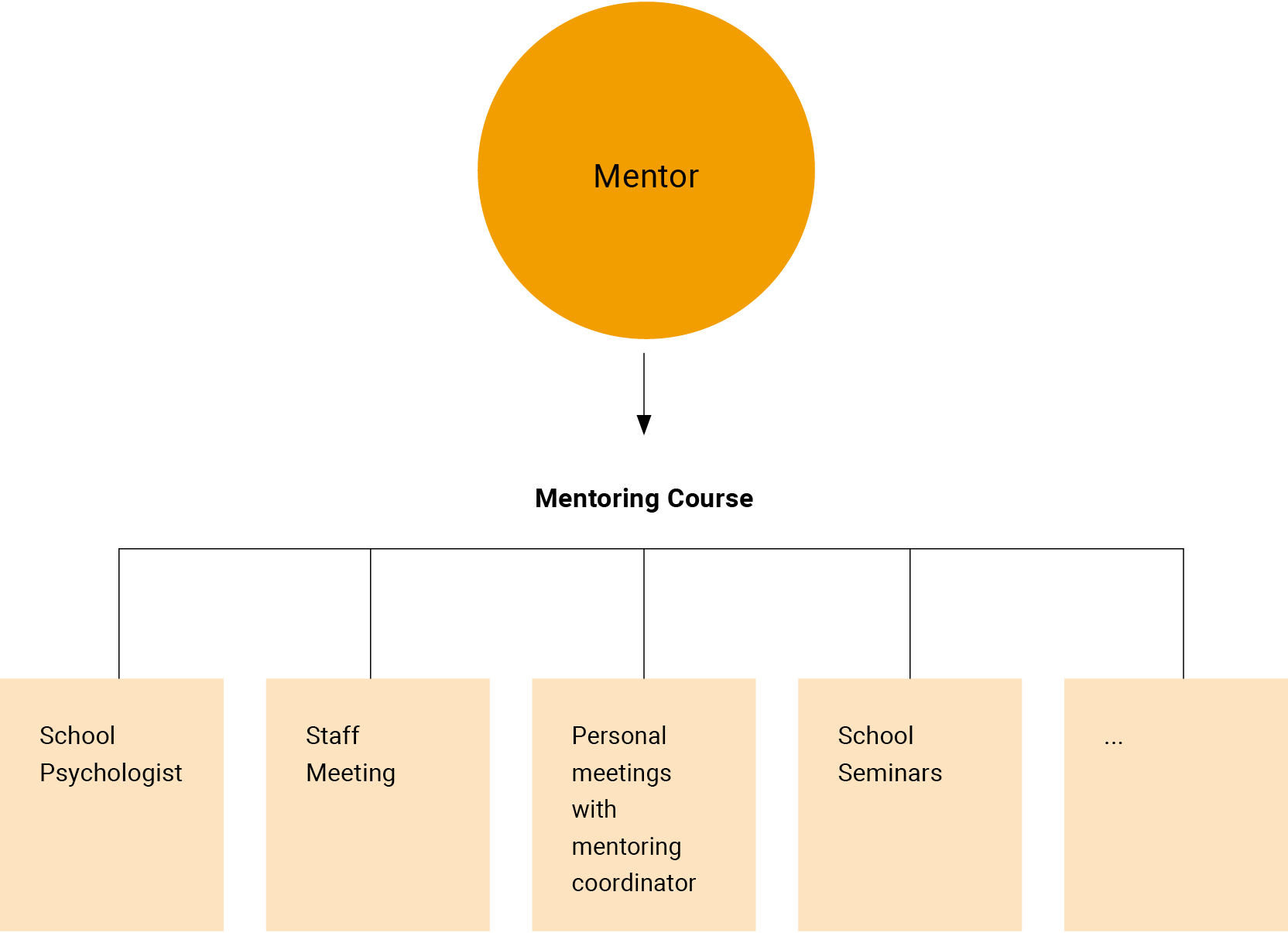

How to support Dialogic Mentoring?

Understanding mentoring as a profession that needs to be learned, practised and constant support, it makes sense to create spaces where dialogues are of central meaning.

Figure 11: What Dialogic Mentoring needs (own figure)

As Figure 11 shows, beneath a certain course for Dialogic Mentoring the exchange with a school psychologist or with other mentors in the staff meeting can be a continuous support. Very helpful are personal meetings with the coordinator for Dialogic Mentoring processes and of course seminars in the school are a huge support for all mentors to establish the attitude of Dialogic Mentoring in their field of action (Simri, 2020).

What supports mentors intending Dialogic Mentoring?

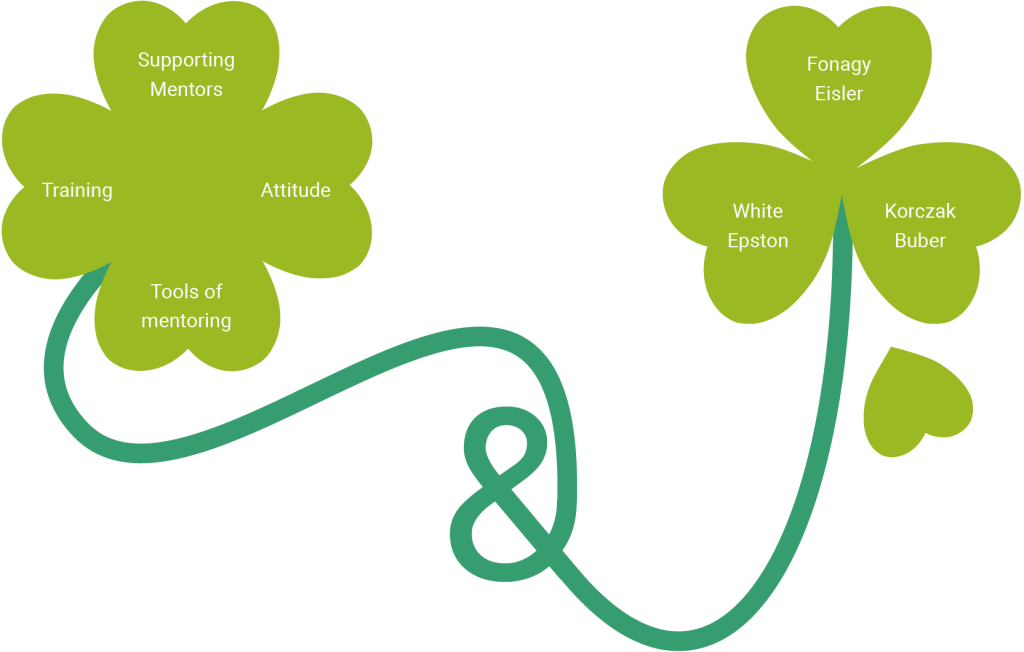

Beneath the above an ongoing training would be an appropriate support for mentors in the field of Dialogic Mentoring to reflect on their own attitude and to widen their competences of Dialogic Mentoring processes. This ‘crimson’-side is urgent, as shown in Figure 12:

Figure 12: Dialogic Mentoring is to be supported (own figure)

And there is an additional ‘clover’, proving that nothing is new about the ideas of dialog and mentorship; here the names of Martin Buber (1937, 1966) Janusz Korczak (1919, 1929, 1939), David Epston (Epston & White, 1992; Epston, Freeman & Lobovits, 1997),, Michael White (1995, 2004, 2007), Riane Eisler (2000, 2003, 2004, 2015, 2017, Eisler & Loye, 1990, Eisler & Fry, 2019) and Peter Fonagy (Fonagy et al. 2000) are arising – and the fourth leave symbolises, that there are a lot more witnessing authors supporting all that is needed for Dialogic Mentoring. Some examples of such sources will follow in our last chapter to encourage all for all readers to deepen and to nourish their attitudes to existential human needs, not only in school-life: Dialogic Mentoring.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

What are further questions about Dialogic Mentoring?

If it is true, that the more we find out, the less we know – then let us collect some new arising questions that occur from the circle we created around Dialogic Mentoring (see Fig. 13).

Figure 13: More questions than answers? (own figure)

Three people with three extremely different backgrounds sit together in a circle and focus on a centred topic: Dialogic Mentoring. And still there is an empty space in the middle with questions.

Three people with three extremely different backgrounds sit together in a circle and focus on a centred topic: Dialogic Mentoring. And still there is an empty space in the middle with questions.

Still crazy after all these words? A final thankful thought: The week of our common teamwork took place in Ireland while in Israel people demonstrated for the continuity of democracy. When we said “Farewell” this summer we could not even imagine the horror of the 7th of October and all that followed. Sinead O’Connor (08.12.1966 in Dublin – 26.07.2023 in London) – famous for “Nothing Compares 2 U”, a message fitting to the intention of Dialogic Mentoring has a gift of words for us now: “Thank you” stays for what we all are longing for – always:

“Thank you for hearing me … Thank you for loving me… Thank you for seeing me … And for not leaving me….Thank you for staying with me… Thanks for not hurting me … You are gentle with me …Thanks for silence with me… Thank you for holding me …Thank you for helping me…”

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

There may be a lot of different questions and tasks around Dialogic Mentoring depending on their background and contexts.

- How does a Dialogic Mentor deal with mentees of different ages?

- What is the relation like between the mentee and the parents during the process of Dialogic Mentoring?

- Is Dialogic Mentoring only working in a bubble of ‘milieu’ where Democratic Schools are working well? What about socially disadvantaged areas and state schools?

- How could you implement dialogic mentoring into your future school practice? Does it only work if the whole school commits to dialogic mentoring or how could it be implemented in your classroom or grade?