Section 4: Fostering Student Well-Being and Emotional Health

Enhancing Minority Languages for Inclusion

Petra Auer; Beausetha Juhetha Bruwer; Pamela February; Federica Festa; and Ulla Sivunen

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Initial questions

- How can we implement a learning environment that enhances minority languages and makes learning accessible for all learners?

- Are there common strategies that can be applied to different scenarios?

Introduction to Topic

“Language learning [or learning in general] becomes a different issue seen from the perspective of the speakers of a minority language […]” (Gorter, 2007:1). In contrast to students speaking the language of the majority community, who speak the language at home with their parents, and at school it is the only subject and medium of instruction, however, this is not true for students of a minority language community. Instead, what they encounter in school is a mismatch between the language they speak at home – their first or native language(s) (for example, L1) – and the language they encounter in the classroom (Gorter, 2007). As the example case illustrates, students’ first language(s) is their language(s) of thought, emotion, identity and the construction of knowledge (Cummins, 1981; Gibbons & Ramirez, 2004; Lange & Pohlmann-Rother, 2020). It can therefore be deduced that learners who are speakers of a minority language and attend schools with a “monolingual habitus” (Gogolin, 1994) face an increased risk of exclusion or marginalisation. The following section elaborates on how the enhancement of minority languages can foster the inclusiveness of schools or education systems in a broader sense. Before that, however, we want to venture a definition of the terminology.

Key aspects

What do we mean when talking about minority languages?

The concept of “minority language” can be understood as controversial, which mainly arises from the fact that the term “minority”, no matter from which discipline it is seen, is problematic (Gorter, 2006). The endeavour to define what is a minority and what is not, to set criteria for who belongs to a minority group, is a very complicated one (Laakso et al., 2016). Very often, minority language is simply defined as the language spoken by less than a certain percentage of a population in each geographic context (for example, region, state, country), that is, it is about the size of the speaker population within a specific territory (European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, 1998; Grenoble & Singerman, 2014). Contrary to this, Garcia (2006) defines “minority language education[…] as the school’s use of a language (or languages) spoken by students whose heritage language differs from that of the more powerful members of society who usually exercise the most control over state schools” (Garcia, 2006; 159). Her definition does not refer to numbers but rather to language status and associated power relations. Thus, the question arises as to which language is dominant rather than how many people speak the language in that situation. Finally, it can be added that different types of minorities exist; old or traditional (i.e., indigenous, autochthonous) versus new minorities (i.e., migrant). In this regard, it needs to be stated that some of these nominations are discussed controversially and very often, borders between one type and the other can be fuzzy (Laakso et al., 2016).

It becomes evident that when it comes to minority languages, we might meet various and sometimes even conflicting definitions and understandings of what a minority language is. The above example case depicts a lone learner who does not understand what is happening in the classroom as their home language is different from the language of instruction. It may be familiar to you, as this situation is happening in classrooms around the world daily. You might also notice the risk of exclusion that lies within the fact that a learner does not understand what is going on in the learning situation (De Korne, 2021).

In the following, we are going to examine in closer detail four scenarios that depict diverse (language) learning situations that may make you think about the topic differently. These scenarios will be accompanied by the specific language policies that underpin them and the realities of each of the instruction contexts within which the learners in these scenarios find themselves. In this way, we try to illustrate how the concept of minority language is strictly related to and interwoven with contextual and structural factors such as the policy context of the nation-state, which, for instance, plays a crucial role in defining which language varieties obtain minority status and thus rights and protection (Gorter, 2006), and consequently, is given importance and space in education and in the classroom.

Description of a structural disadvantage and how to address or prevent it through the use of four scenarios

Scenario 1: Finnish Sign Language and the case of a deaf learner

Deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH) pupil named Jenna is schooling in a classroom using spoken language, Finnish, with a hearing teacher in an environment where others do not know a national sign language, Finnish Sign Language (FinSL). Jenna herself has started to acquire FinSL with her family. In this scenario, how can she learn and acquire FinSL in a non-signing environment where the teacher and other classmates do not sign? Also, how does Jenna understand what is spoken in the environment, and what the teacher is teaching? How can we support Jenna’s evolving bilingualism and DHH identity? Why is Jenna in this situation?

Language Policy

According to various estimates, there are more than 70 million deaf people in the world, and an even larger number who are hard of hearing (World Federation of the Deaf, 2023). Signed languages, like spoken languages, are natural, complete, and independent languages in the visual-gestural modality that have emerged in deaf communities around the world over time. Each country has its own signed language and even more than one, like in Finland, there is a FinSL and Finnish-Swedish Sign Language (FinSSL). Signed languages have been researched for decades in the field of sign language linguistics (Brentari, 2010) and Deaf Studies (Gertz et al., 2016), but still, public knowledge of these languages and communities seems to remain quite limited.

The status of sign languages varies in different countries in Europe and around the world. Recently many European countries have acknowledged sign languages in their legislation (Murray et al., 2015). In Finland, sign language was recognised in 1995 and the Sign Language Act, concerning both national sign languages, was enacted in 2015.

DHH people who use a signed language are a group with a unique double status – are not only a linguistic minority but also a disability minority. The rights and needs deaf and other people with diverse hearing status, should therefore be seen from different and complementary perspectives.

The majority of DHH children, over 95%, are born to hearing parents, most of whom do not know a national signed language, so DHH children do not automatically learn a national signed language (Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004). In the case of DHH children, hearing parents who do not know a national signed language also have to learn a new language with their children. Ensuring bilingual education and support in a national signed language at different educational stages and in public services for families is crucial for a DHH child’s balanced bilingual development and growth with full linguistic accessibility.

Instructional context

Current situations are always shaped by history. There have been, for example, also serious human right violations in Finland, like sterilisations as part of racial hygiene policy efforts and deaf people have been forced to speak and the use of sign languages has been banned in education (Katsui et al., 2021). In Finland, this history has contributed to the beginning of a unique national truth and reconciliation process about the injustices done to the sign language and deaf community. It is similar to that of the Sami minority, where the truth and reconciliation process began earlier (Katsui et al., 2021).

Deaf people’s language proficiencies have often been controlled by normative standards, such as deaf children’s national sign language learning being restricted by governments, early invention and so-called “inclusive” education system (Snoddon, 2022; Snoddon & Paul, 2020). Many DHH children in mainstream schools are isolated with other non-signing children in the classroom without support services (Murray et al., 2018). Henner and Robinson (2023) find that DHH children very often experience language deprivation and lack of linguistic capital because they do not have access to a community of languages inside and outside school and they do not have fluent signers around them. Snoddon (2022) describes this situation as social and epistemological violence against deaf bodies and deaf ecosystems, as the education system deprives children of direct instruction in a signed language and access to the signing community of DHH peers. There is an intergenerational transmission that has been disrupted by so-called ‘inclusive education’, resulting in a loss of identity for DHH children (Snoddon, 2022).

Recent research shows that pupils in special education have a much better chance of receiving instruction in a signed language than those in mainstream education in Finland (Katsui et al., 2021). This can be a difficult situation for families who would like their children to attend a local school, and to be taught in a bilingual way with signed language (FinSL/FinSSL). Advanced hearing technology and its practices has contributed to the contradiction between medicalisation and rehabilitation discourse and the linguistic-cultural view. This dual distribution and discourse can still be seen in the field of education, thus leaving bilingual education in a signed language on the margins of education.

Scenario 2: Migrant Students and new minority languages

Enson is a 15-year-old student. His family is originally from Albania and moved to South Africa when Enson was four years old. As a result, Enson speaks both Albanian and English as a native speaker. Last year he arrived in Italy as an unaccompanied minor because he had been recruited by a professional football team. He initially enrolled in a scientific secondary school because of his excellent maths results in South Africa, but he failed. He is now in the first year of a commercial vocational school. Why is Enson in this situation?

Language policy

In Italy, according to the Ministry of Education (MI, 2024), 11.2% of the students are migrant students; more than half of them (65.4%) were born in Italy, others arrive, like Enson, when they are already grown up. For the school year 2022/2023 it was observed that there was a decrease in the total school population (-1.2%). The number of students with Italian citizenship declined (-2%) while those students with non-Italian citizenship showed a growth (+4.9%). Italian citizenship is transmitted through jus sanguinis, that is, students born in Italy as children of parents who are both non-Italian citizens are considered migrants in the statistics. Linguistically speaking, many of the students are new minorities that are gradually becoming part of the national historical heritage. Almost half (44.4%) of the students with non-Italian citizenship are of European origin, but there are almost 200 countries from which students originate.

According to Italian law, students under the age of 18 have the right and duty to be educated and must be enrolled in the grade appropriate to their age. In practice, however, many secondary schools refuse or discourage the enrolment of migrant students on the grounds that their level of Italian is considered insufficient to enable them to succeed in school (Bonizzoni et al., 2006; Barban & White, 2011; Romito, 2014). So, these students often choose a vocational or technical school, regardless of their previous educational background. It is also very common for migrant students to drop out of school. Sometimes, because they fail, other times, because they are placed in classes below their age (despite legislation). According to the Italian Ministry of Education (MI, 2024), more than one quarter of foreign students aged between 17 and 18 drop out of school, with a strong gender difference that sees the schooling rate of female students’ 20% lower than that of males.

Enson’s story is very common among migrant students and indicates that the presence of new minority languages is regarded as a problem, even though Italian law (Law 482/1999; MIUR, 2014) and common European and international documents (Council of Europe, 1992; Pasikowska-Schnass, 2016) affirm that the presence of many national, regional, old and new minority languages spoken in Europe enriches the common cultural heritage. The proportion of low-achieving migrant students exceeds that of native-born students in most European countries, even when socio-economic status is controlled for (OECD, 2016).

It seems that teachers, in spite of the legal guidelines, give different values to the different languages and thus they appear in a hierarchy. If Enson had been the son of an English couple who had just moved to Italy, would the school have thought of rejecting his enrolment? In Italy, the law has been protecting linguistic minorities since the Constitution of 1948, and some regions have a bilingual or even trilingual education system. Instead, for example, the Romanì language, which historically is considered a minority in Italy, is not recognised as such by the law (Scala, 2021), and the same is true for other regional languages.

Instructional Context

As we can see, theoretical principles and policies are often not applied in everyday school life. Very often teachers ask learners to exclusively use the language of instruction at school and to avoid their native language or languages. So, Enson is a typical case of a heritage speaker. On the one hand, the immersive situation allows students to learn the target language very quickly, but on the other hand, it seems to be a demand for cultural assimilation.

In Italy, foreign students are immediately placed in mainstream classes where they learn the language of the school as a second (or third, or fourth, …) language in an immersive way, since any form of special schooling has been abolished in Italy since the 1970’s (Law 517/77). Only for pupils who have been in Italy for less than a year are schools obliged to activate L2 courses during school hours, and it is more common for schools with a high presence of pupils with non-Italian citizenship to be well organised to support the L2 learning path both for newly arrived pupils and for all levels of academic language learning as L2. In fact, any other Italian L2 course is only activated when the class council/teaching team deems it appropriate and with the agreement of the pupils’ families, as the law stipulates that language learning must be predominantly immersive, through the adaptation and personalisation of the curriculum (C.M. 24/2016). The most recent legislative provisions allocate resources to schools in the form of specialised teachers for the teaching of Italian as a second language and funds for the activation of courses, but only to schools with at least 20% of foreign pupils. The percentage of pupils with non-Italian citizenship in science high schools is 4.3%, while in technical and vocational schools it ranges from 9% to 28.4% (MI, 2024), so science high schools usually do not have Italian L2 courses, but exceptions to the average can be found, both virtuous and less so.

Despite studies (D’Anglejan, 1988) showing that it takes about one year to learn the basic interpersonal communication skills of a new language and about 5 years to achieve cognitive academic language proficiency, bilingualism is still a disadvantage in formal education, so much so that 53% of foreign pupils are behind their age group at the end of secondary school (MI, 2024).

How can Enson’s teachers change their attitudes, possibly changing the outcome of his studies and supporting him on his path of growth and identity construction as a migrant and multilingual person? In this scenario, there was no suggestion that Enson should do his studies in his mother language at the same time as learning Italian. Study material in English could have been found easily and the use of translators could have been encouraged. Additionally, it would have been possible to activate the Albanian-speaking community in Turin, or to look for other Albanian- or English-speaking students in the school or in similar schools. What kind of teacher knowledge would have been necessary to activate these resources?

Scenario 3: Official Minority Languages in a multilingual context

Giulio is in his first year of primary school and just started learning German as a second language. At home, he speaks Italian with his mother, his father, his little sister Francesca, his nonna (grandmother) and his nonno (grandfather). With all his friends from kindergarten, he primarily spoke Italian, even if it was not always everybody’s native language. He learnt some words in Albanian and Moroccan from his friends there. However, learning German is a totally new thing for him, so in the first days of school he struggled because he does not understand what the German teacher is telling him. Why is Giulio in this situation?

Language Policy

The Autonomous Province of Bolzano, a region in Northern Italy bordering Austria and Switzerland, is characterised by a specific ethnolinguistic reality with three different ethnolinguistic groups historically cohabitating on the territory: Italian, German and Ladin (Nössing, 2017).

With the end of World War I and according to the peace treaties of Saint Germain in 1919, the province, which before was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was annexed to the Italian Kingdom (Steininger, 2004). Due to this annexation, German and Ladin became linguistic minorities within the Italian Empire. In 1922, with the fascist takeover of power, the so-called time of Italianisation began, a forced assimilation of the German- and Ladin-speaking inhabitants (Voltmer et al., 2007). After World War II, the latter started striving for the province to become autonomous to ensure their language and culture were protected, which at times also took on violent overtones (Alcock, 2001). Consequently, tensions and mistrust dominated the relationship between and coexistence of the three language groups for a long time (Baur, 2009). In 1972, the Second Autonomy Statute came into force, which implemented a series of provisions (for example primary responsibilities for public services, agriculture, kindergarten and school buildings; introduction of a quota system to regulate access to public positions; autonomous administration of the school) guaranteeing the protection of minorities and aimed at setting the pillars for a peaceful coexistence of all.

Nowadays, all three languages share the status of official languages and Ladin and German are further recognised as minority languages within the Italian nation-state and protected as such by law (Nössing, 2017). These historical events and the resulting legislation led, among others, to a tripartite division of the education system according to the “language groups” (i.e., the establishment of three parallel school systems, each with its administration, education authority, directing body, and evaluation board) (Wisthaler 2013). Consequently, all educational institutions from kindergarten to secondary education are separated by language.

Instructional Context

In the territory, you can find schools in the German, Italian and Ladin language. However, children and youth in school learn the other official language(s) as second/third language(s) (i.e., in German schools Italian is thought as L2, in Italian schools German, in Ladin schools both German and Italian as L2 and L3). While the Italian and German educational institutions can be defined as “monolingual schools” (Baur, 2009), where the second language is taught as a subject for a certain number of hours per week, Ladin schools follow a “parity model” (Rautz, 1999). Here, an equal number of lessons are taught in German and Italian, and Ladin is taught as a subject creating a trilingual school model. More specifically, Ladin is used as a teaching language in kindergarten and an auxiliary language in primary school. In first grade, literacy is achieved through Ladin and one of the two other official languages, Italian or German, and the respective third language is taught for at least one hour per week with the aim to respond individually to the child’s language skills. From the beginning of second grade equal use of German and Italian is applied (Verra, 2008, 2011).

Even though, having schools in each of the official languages was initially implemented to protect the linguistic minorities, recently, scholars also address the current situation critically as contributing to the creation of parallel worlds because the strict separation hinders daily contacts between the children of different language groups (Baur, 2013; Gross, 2019; Zinn, 2017, 2018). It is the case for Giulio, who has no German-speaking friends, even though Hannah lives next door; she also just started primary school in the exact same building as Giulio, but their classrooms are on different floors, and the break time is not the same. As the statistics show, the chance that Giulio and Hannah will ever become friends is small. A survey from 2017 showed that 90% of the interviewed youth stated having many friends of the same language group. Further, only 23% of those interviewed considered the co-living of the different language groups as a positive aspect of the province, and only 20% identified the division among language groups as problematic (ASTAT, 2017).

Therefore, taking an inclusive perspective, one of the central questions regarding the Province of Bolzano is “[…] whether the policies aimed at protecting the historical traditional minorities in South Tyrol help or hinder the creation of a tolerant and pluralistic society […]” (Medda-Windischer, 2015: 101). Even though the Italian school system in terms of its structure and the long tradition is one of the most inclusive education systems around the world, when taking the perspective of languages, the inclusiveness of schools in the Province of Bolzano might be questioned (Auer, 2023).

Scenario 4: The official language of instruction is not native to anyone

Elina is a Grade 3 learner from Namibia who speaks Khoekhoegowab at home with her parents, her friends, and everyone else in her community. She loves interacting in her language with her friends, as the “click” sounds of her language are music to her ears. Elina and many of her friends go to an Afrikaans school, because of a lack of Khoekhoegowab schools in the area where she is staying. In school, Elina’s teacher teaches in Afrikaans, which makes learning difficult for Elina as she does not always understand what the teacher is saying. In addition, Elina must also learn to read and write in English, which is even more confusing as she only uses English at school. Why is Elina in this situation?

Language Policy

In Namibia, the language policy states that from Pre-primary to Grade 3, learners should be instructed in their home language, with English offered as a subject. Grade 4 is a transitional year where English becomes the primary medium of instruction and the home language is taught as a subject (MEC, 1993). The objectives of this policy were to promote the equality of all national languages in Namibia and to ensure that all citizens had a sufficient level of English proficiency to support the establishment of English as the official language (Norro, 2022). Although this is the language policy, it is not always implemented in the prescribed manner, as seen in Elina’s case.

According to Kamwangamalu (2013), two opposing ideologies, decolonisation, and internationalisation have influenced language planning in post-colonial African nations. In contrast to decolonisation, which involves replacing the ex-colonial language with indigenous languages, internationalisation results in the preservation of the ex-colonial languages to gain economic advancement and greater communication. Globalisation has most recently expanded and strengthened the internationalisation ideology. In order to provide their children with an equal chance to prosper in the new global order, more parents are insisting that their children learn English, which has increased the language’s significance (Norro, 2022).

Interviews with people from various ethnic groups in Namibia revealed that the majority of parents, teachers, and learners agreed that English should be the primary language of instruction and that it should be taught in the first year of primary school. They believe that early exposure to the language will accelerate learners’ fluency in it and that people who cannot speak English are unable to contribute effectively to society (Chavez, 2016). The leniency with which the policy is applied in schools makes this another reason why many learners do not receive early primary education in their home languages. For example, if schools can demonstrate that there are a significant number of residents from other language communities in the area, they may apply to the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture to teach in English from Pre-Primary to Grade 3 while using the learners’ home language/local language as the second language. In this sense, English becomes superior to local languages.

Instructional Context

Statistics showed that only 42% of Khoekhoegowab-speaking learners have Khoekhoegowab as their medium of instruction (February, 2018). As Elina’s language is a Khoisan language, which is different from the Afrikaans language, which has a Germanic root (Norro, 2022), it is difficult for the teacher to accommodate Elina and her friends in the class. The teacher does not understand Elina’s language and struggles to explain the content of the lessons to Elina and her friends. As she is not familiar with Khoekhoegowab, she can also not use code-switching to make the learning process easier. This is an unfortunate situation, but it is a common situation in Namibia where learners are taught in a language that is not their native tongue. The scenario of the Namibian situation (in terms of the number of Khoekhoegowab-speaking learners) is indicative of the power of a dominant language that is legislated to be taught to the learners in spite of their heritage language.

The fact that learners are taught in a second or third language that they find challenging to grasp makes learning difficult for them. Often, they find themselves in a situation where they have to learn a language at the same time that they have to learn in the language. In Elina’s situation, she has to learn Afrikaans at the same time that she learns in Afrikaans. She is also consecutively introduced to English as a subject in which she needs to gain a level of proficiency that will enable her to read and write in the language. In these situations, the learners’ self-esteem and confidence in their ability to speak and write in the instructional language may suffer. Learning in these circumstances can lead to frustrated learners, as they may feel that their own language and cultural experiences have no place in formal education. They may face the situation of being looked down upon by those more fluent in the language of instruction and characterised as underachieving and slow. This can result in them avoiding situations where they have to express themselves using the language of instruction (Motitswe & Taole, 2016).

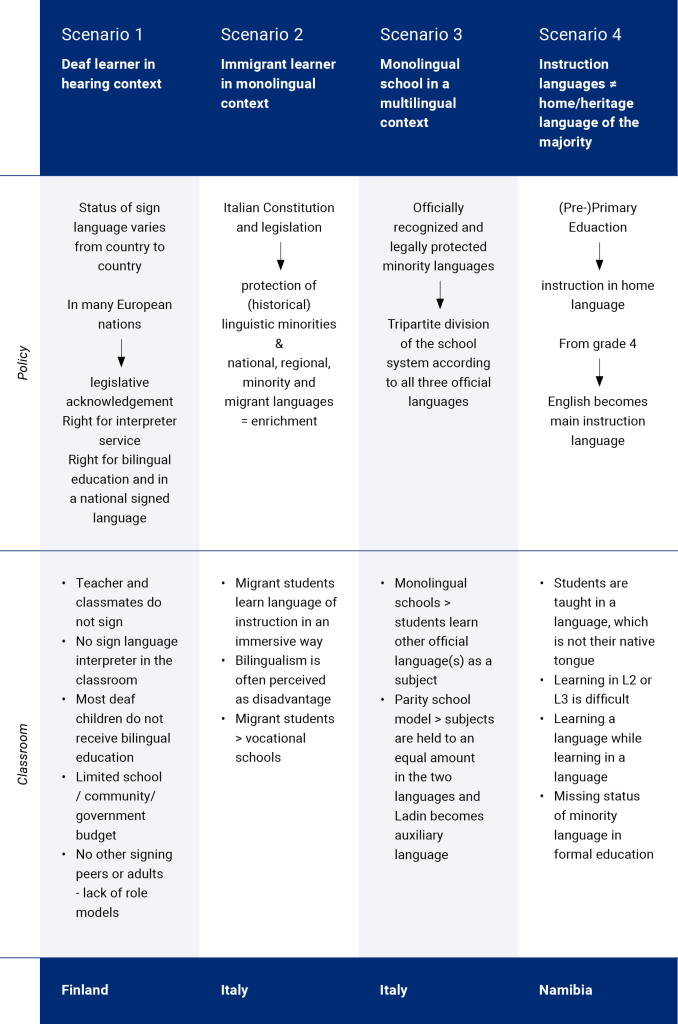

Figure 1: The four scenarios at a glance

To sum up, Figure 1 provides an overview of the four scenarios just presented. As represented in these scenarios what we are talking about when using the term “minority language” can be very different and is strongly related to language policy and contextual factors. Further, the scenarios demonstrate the complexity of the different classroom situations. You may typically have assumed that minority language is a case of the lone learner who speaks or uses a different language than the rest of the class, for example, the case of the deaf learner who uses Finnish Sign Language (Scenario 1). In Scenario 2, in addition to the case provided, there is also a discussion of several migrant learners who speak different languages to those taught at the school. Instead, in Scenario 3, the fact that the minority language(s) are officially recognised and protected by law leads to monolingual schools in a multilingual context. In the Namibian case (Scenario 4), the Khoekhoegowab learners are the majority in the class but do not reflect the language of instruction, Afrikaans and English. Despite the individuality of each of the scenarios, in the following, by responding to two initial questions, we try to elaborate some overarching possibilities for action, which might be applicable for all four and even other possible scenarios of minority languages in educational contexts.

Enhancing minority languages

Over half the world’s population is bilingual and many people are multilingual. In China, for example, there are 56 nationalities that use around 80 different languages (Fang, 2017). According to the Atlas of the World’s Languages of UNESCO (n. d.), “language is a carrier of human heritage, a local knowledge repository system, a system for communicating between people and a regional, national and global economic-political resource to be managed as an asset along with natural, human, financial and other resources, as part of good governance and societal development” (UNESCO, nd). Schools and teachers, but also more broadly, education authorities and the surrounding community play a role in how a minority language is preserved for future generations and what development opportunities it has (European Commission, 2019). This is particularly important in the case of small national minority languages, which may have only hundreds or a few thousand language users. The situation is different in the case of transnational languages with a large community of users. These languages often have more resources, for example in the form of networks, institutions, and learning materials. Instead, for instance, signed languages often have very few materials appropriate for primary education and different subjects (Katsui, 2021). According to the World Report on Disability (Lancet, 2011), people with disabilities, including the deaf, are the most discriminated group in the world. Deaf people are socially disadvantaged and vulnerable in many parts of the world, and are often denied access to education, among other things (Lancet, 2011). The World Federation of the Deaf and many researchers, consider the use of signed language and education in a signed language to be a human rights issue (Murray, Meulder & Maire, 2018). Similarly, indigenous people, who represent a significant part of the world’s vast cultural and linguistic diversity and heritage, often do not have access to schooling in their traditional languages (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UN DESA], 2017).

As argued previously (see Introduction), it is not only about preserving minority languages around the globe, but from an inclusive perspective, it is about responding to the diversity of all learners through the removal of barriers and the prevention of exclusion, which can arise from specific attitudes towards the many possible facets of diversity (Ainscow et al., 2013). Language can be understood as one of these facets and therefore needs to be taken into consideration in the realisation of inclusive education as a human right and as groundwork for a more equitable society. Therefore, it needs to be asked, how schools can provide all students with the opportunity to learn, to play an active citizenship role, and communicate a policy of equal value for alllanguages.

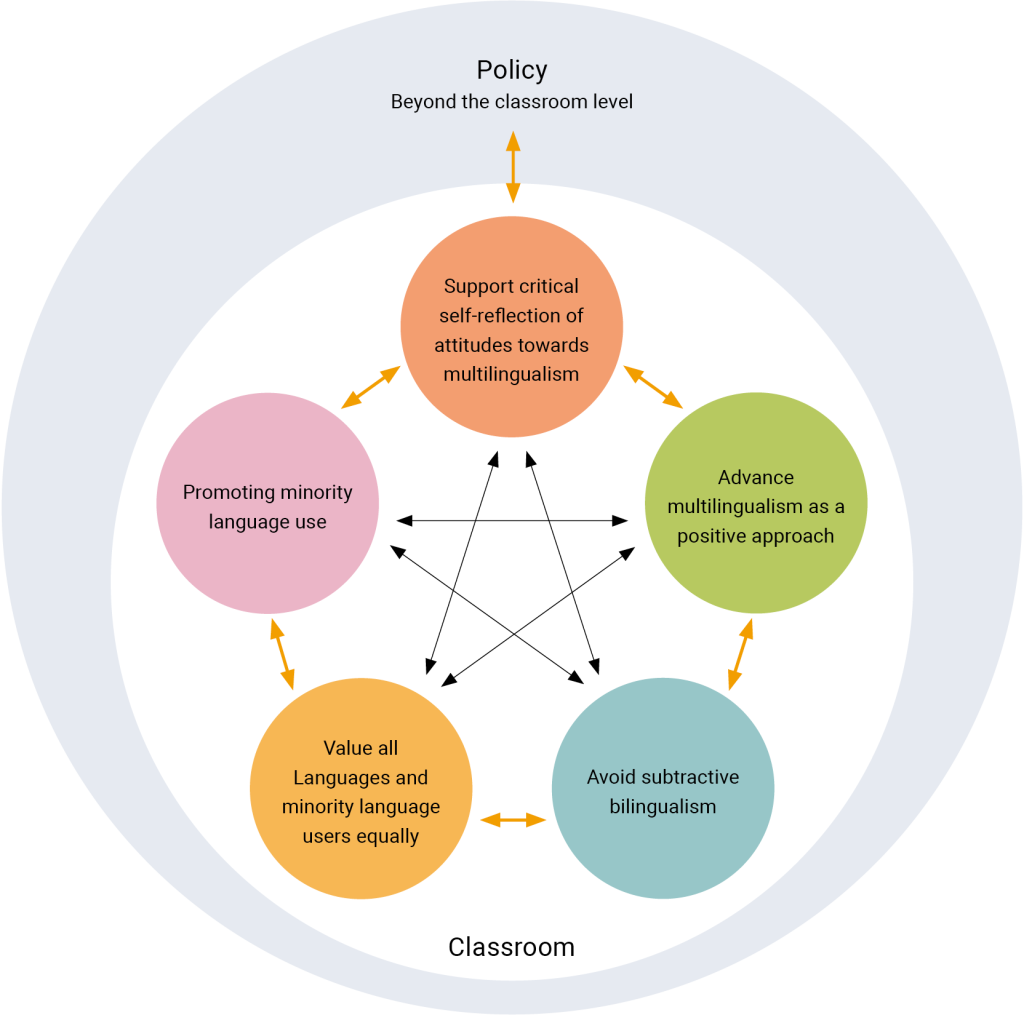

In this regard, it is believed that the school community, as well as the wider society, could respond in the following manner. In Figure 2 there is an overview of six possibilities for action in terms of approaching the goal of a more inclusive education from the perspective of minority languages. As can be seen, five of them can be located in the classroom or school level, while one of them operates at a higher level of legal anchoring. Further, certain strategies will lead to another creating a recurring circular structure in their application but essentially, they are all interrelated in a reciprocal way, which is why the application sequence can be flexible, reversed, or swapped.

Figure 2: Strategies to enhance minority languages for inclusion

Support critical self-reflection of attitudes towards multilingualism

The construction of plurilingual language environments and opportunities is also influenced by the teacher’s own perceptions and attitudes (Heller, 2007) as part of the school culture. It is therefore important for teachers to reflect on their own perceptions of multilingualism and multilingual learners.

Among the various directions taken by research on multilingualism education, teacher training is one of the main fields of action for integrating pluralistic approaches into a language policy open to plurality. Teachers need to be stimulated to adopt a reflexive attitude that makes them critical of the representations and certainties related to the profession and teaching disciplines. Just as the focus in the classroom has progressively shifted from the subject to the methodology and finally to the learner, so teacher training, which was mainly based on the transmission of concepts and know-how relating to classroom management, has more recently recognised the centrality of the trainee teacher’s individual experience.

Pluralistic approaches, as a way of looking at language teaching and because of the challenges they pose to many preconceptions about languages and language learning, are an ideal way to promote education based on reflection, critical thinking and collaboration. Many factors come into play when teachers relate to languages, which are difficult to identify if they are not critically recognised in their own training: the social status that distinguishes each language, the possibility of appropriating them, the hope of their practical usefulness in the future, and the affective dimension (Blondeau & Salvadori, 2020). For instance, in the Scenario of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano it seems to be important – due to the historical events and ongoing tensions between the different language groups (the three language groups live together separately and ethnic conflicts still occur) (Baur, 2009, 2013; Carlà, 2007; Heiss & Obermair, 2012) – all those involved in education critically reflect their own language history and attitudes towards the other official languages. As Baur (2013) argues, in the case of the Province of Bolzano, the coming together of the language groups and the acquisition of multilingual and intercultural competences depend not only on contacts and cooperation but also on joint processing of the historical trauma, which alone can produce a sensitive understanding of societal equality.

Literature suggests many strategies that can be used to develop greater awareness of multilingual identity. The linguistic autobiography (D’Agostino, 2012; Andrade et al., 2020) is an example of a tool to reflect on the complexity of everyone’s linguistic history. A linguistic autobiography is a personal narrative or account that focuses on an individual’s experiences of and relationship with language throughout his or her life. It usually includes information about the person’s linguistic background, including the languages they speak, their language learning experiences and the ways in which language has shaped their identity, culture and communication. Language autobiographies are often used as a tool for self-reflection and as a means of exploring the complex interplay between language and personal identity. For this reason, this technique has been tried and tested in the in-service and initial training of teachers working in multilingual contexts. Other similar tools that can be used in teacher training include Identity text (Cummins, 2010), which are written or visual representations, such as essays, stories, drawings, or any form of creative expression, that allow individuals to explore and express their own cultural and linguistic identities.

Advance multilingualism as a positive approach

The term “multilingualism” has many definitions. The term can refer to multilingual individuals or locations where multiple languages are spoken. Therefore, it may be useful to apply the Council of Europe’s distinctions between plurilingualism and multilingualism (Lid, 2018). Plurilingualism is defined as the quality of an individual possessing a “plurilingual repertoire” of language competences, and multilingualism is the attribute of a place, city, society, or nation-state where many languages are spoken (Council of Europe, 2007). Even with precise definitions, the description and perception of multilingualism can occasionally change from one context to another.

A common view of multilingualism is having a population that speaks or understands two or more main languages learnt in school in addition to one or more national languages. Some will define multilingualism as the ability to distinguish between languages that are considered “valued” and those that are not. With very rare exceptions, the languages of relatively recent immigrants continue to be those that are considered to have less significance than the extremely important languages of communication, such as English. In some African countries, there are children who can speak more than one language before they start primary school. They learn one language at home, one or more in the neighbourhood, and then a third or even fourth language at school, where it serves as the medium of instruction (Lid, 2018).

The way people think of multilingualism is as varied as its reality. Linguistic diversity and multilingualism have often been seen as problematic, with monolingualism being considered a more natural and preferable option. Many parents and educationalists believed that having more than one language was detrimental to cognitive development or at least caused some confusion (Cenoz, 2012). However, studies show that multilingualism has a positive impact on cognitive development and meta-linguistic awareness (Baker, 2011) and it seems that professionals are beginning to make more use of learners’ entire linguistic repertoires in foreign and second language (L2) education (Taylor & Snoddon, 2013).

The number of multilingual students in European schools and elsewhere has increased recently, which has prompted a re-examination of multilingual student models to enhance multilingual students’ academic performance and participation (Duarte & van der Meij, 2018). Considering our four scenarios, which include a national language, a minority language, a foreign language, and numerous immigrant languages, it can be difficult to meet the requirements of multilingual education in an educational system that reflects these realities.

If schools strive for multilingualism and multiliteracy, then multilingual education is the use of two or more languages in the classroom. As such, it serves as a catch-all phrase for a variety of pedagogical strategies that make use of several instruction languages, as well as those that seek to promote elite bilingualism. Using students’ family languages as a resource for instruction is a typical element of many new programs designed from a multilingual education perspective (Duarte & van der Meij, 2018).

Translanguaging is one of those novel linguistic subjects that scholars are interested in studying. It refers to the act of multilingual people using their whole language repertoire to communicate, or more specifically to learn in an academic environment. A translanguaging approach to teaching would mean that multilingual students would have the opportunity to use any language they have access to in a school setting. Although it was always thought that a teacher conducting a language exercise in a L2 setting had to do it exclusively in L2, researchers are now attempting to develop new educational approaches for bilinguals considering the large-scale migration. As a result, translanguaging was presented as a means of bridging L1 and L2. Students can use their whole language repertoire in a translanguaging classroom, and they can switch between L1 and L2 at different points during the learning process (Evgenikou, 2017).

Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of a translanguaging pedagogy at various school performance levels for both new and old minority languages. According to Duarte and van der Meij (2018), some of these benefits include:

- better lesson completion,

- balancing the power dynamics between the languages in the classroom,

- minority language protection and promotion,

- increased participant, confidence and motivation,

- learning maximisation,

- language empowerment,

- and higher cognitive engagement in content matter learning.

In the past, bilingualism, or multilingualism, was viewed as a hurdle in educational environments, resulting in the separation of languages. However, with translanguaging pedagogies, all languages spoken in a classroom are purposefully and systematically utilised to improve learning outcomes and recognise all students’ linguistic diversity and abilities. By providing encouragement and training for teachers to strategically use translanguaging practices, the focus can shift from viewing multilingualism as a problem to continuing to recognise it as a valuable resource (Norro, 2022).

Avoid unbalanced/subtractive bilingualism

The previous section emphasises the shift from viewing multilingualism as a problem and instead encourages the perception of viewing the use of all languages as valuable. Discouraging the use of other languages in school and institutional contexts very often leads to an unbalanced and subtractive bilingualism, in which one or more languages are gradually abandoned and “hidden” because considered less valuable, resulting in a loss of wealth for the individual and society. This is of particular concern when the “hidden” language is the child’s first language.

In direct contrast, additive bilingualism encourages learning the second language while the first language is reinforced. In addition, Garcia and Cole (2014) argue that the common practice of treating two languages as equal but separate disregards the intricate language skills of multilingual learners who strive to balance the power dynamics between multiple languages. This includes efforts to counteract linguistic hierarchies between majority and minority languages, as well as between spoken and signed languages. To give a concrete example, instead of confrontation between spoken and signed languages, the education sector and its authorities should see different languages, cultures and different human abilities as human capital and thus support the bi-multilingualism and identity development of DHH learners in a holistic way.

The growth of bilingualism and the acquisition of a bilingual identity are hampered by keeping one language out of reach of the other (diglossia). Garcia’s concept of “Transglossia” was first introduced as a result of this insight (Garcia & Cole, 2014). Transglossia is a communication network that functions on stable and dynamic principles, where diverse languages function in a mutually beneficial interdependent relationship. It prioritises flexible language practices of bilingual/multilingual individuals over preserving linguistic asymmetries among nation-states and socio-economic groups by upholding two or more of their respective languages. Consequently, the study of bilingualism moves away from defending national languages and ideologies.

In the first scenario, there was a DHH learner in a classroom in a ‘hearing’ environment where others use spoken language. The school could deploy a paired teaching model where two teachers teach in parallel in signed and spoken languages, that is one of the teachers being deaf or hearing person who is fluent in national signed language. The school could also organise an interpreter who conveys the information that enables the DHH learner to access spoken instruction and interaction with others and to express her thoughts in a signed language. These different solutions, such as organising a paired teaching model with suitable teachers, interpreting services and placing other signing children in the same school or classroom supports the DHH learner’s identity development. These arrangements show that the school environment accepts the languages and bilingual and cultural identity of DHH people.

Regarding new minority languages, Unganer (2014) claims through her personal migration experience that language loss or attrition has a huge impact on the individual in various aspects of their life. She recommends the following:

- The establishments of partial immersion and/or cultural heritage programmes.

- Educating the public against hostile and racist attitudes.

- Raising parents’ awareness of the need for proficiency in the second language, while maintaining their first language identities and cultural values.

- Most importantly, second language teachers should promote additive bilingualism over subtractive bilingualism by creating a welcoming environment.

It is believed that these strategies promote a child’s well-being and indicate to the child that all languages are valued equally.

Value all languages and minority language users equally

Minority language is often seen as less important and often ignored. This mindset and attitude reflect linguistically discriminatory thinking, which is also called “linguicism”. It is estimated that more than 40% of the world’s languages are endangered (Harrison, 2007). Throughout the world, the status of deaf people, signed languages, and deaf education has long been marked by the struggle between spoken languages and signed languages, and by discrimination against deaf people and signed languages (Gallaudet University, 2023).

Minority languages are easily overshadowed by majority languages. The different roles and status of languages are often visible in the school environments, because languages are often valued in different ways, as we can see in all the scenarios. In the field of applied linguistics, multilingualism has been examined from perspectives such as language policy, language planning and attitudes towards the use of different languages. When it comes to language learning in the classroom, it is important to provide a more equal status to the different languages coming together in one classroom, be it the student’s native or heritage languages, the language of instruction or the second/third language.

Research has shown that, when the language of origin is used in school, the students’ sense of identity, self-esteem and self-concept are strengthened, whereas when these children are simply placed in ‘mainstream’ education, they are vulnerable to loss of self-esteem and status, and their motivation and interest in schoolwork suffers, with negative effects on performance (Council of Europe, 2020).

To critically address the existing power relations between languages within the school, it is necessary for teachers to work on their own attitudes and perceptions (Section 1), to adopt an approach that values multilingualism in their teaching practice (Section 2), and thus to actively work to prevent their student’s bilingualism from becoming unbalanced (Section 3). However, this is not enough if we do not broaden our view to include the context, which, through its organisation, helps to convey a hierarchy of languages and cultures.

A useful tool in this direction is the observation of the linguistic landscape, which in this particular context, is called the linguistic schoolscape. The term linguistic landscape refers to the visual representation of languages in a particular geographic area, typically in public spaces. Traditionally, when thinking of languages in school, our mind runs directly to reading and writing. The landscape perspective broadens our gaze to classrooms and corridors, assembly spaces, playgrounds, signs posted on doors where staff or students work and where students congregate, blackboard writings, signs, and posters on walls. There images combine with different languages to inform, instruct and/or influence. As Krompák and colleagues (2021) have well demonstrated, multilingual inequalities in schools are often reflected in the linguistic schoolscape, because schools are one of the key institutions in the reproduction of the symbolic order, but the mobilisation of the linguistic landscape can also be a pedagogical tool to pursue broader pedagogical goals, and the use of critical and participatory linguistic landscapes can be an instrument of democracy at school.

Promoting minority language use

In the case of Scenario 1, the UN Convention on the Human Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD, 2016) contains provisions requiring the recognition and promotion of the use of sign languages. DHH-learners’ access to inclusive education on an equal basis with others means delivering education in the most appropriate languages that maximise their academic and social development as per CRPD Article 24. Not providing access to national signed languages constitutes discrimination (International Disability Alliance [IDA], 2020; World Federation of the Deaf [WFD], 2023). Learning and teaching (national) signed languages, sign language-medium education and promotion of positive deaf identity are actions that implement the points of the CRPD agreement which states that “Facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the deaf community” (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [CRPD], Article 24, b) and “Ensuring that the education of persons, and in particular children, who are blind, deaf or deafblind, is delivered in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual, and in environments which maximise academic and social development.” (CRPD, Article 24, 3 c).

Inclusive multilingual education consists of managing learning environments in a way that supports learners’ language learning and linguistic-cultural identity also in their minority languages (L1). It can mean, for example, collaborative teaching, peers and adults using the same minority language, translanguaging, using multilingual media materials, teaching each other one’s own L1 and linguistically sensitive curriculum planning. More examples and solutions for teaching are described also in the Chapter on → Language Learning for All.

One important aspect that enables learners to become fully proficient multilinguals is offering multilingual education based on their L1 (Skutnabb-Kangas et al., 2009). This might be one of the biggest challenges in inclusive education. However, education in a minority language (L1) is important for the preservation and protection of the minority group’s identity since “its capacity to survive as a cultural group is in jeopardy if no instruction is given in that language” (Capotorti, 1979: 84).

Continuing to learn in the L1 by making constant linguistic comparisons with the L2 does not slow down the learning of the L2 but facilitates it. In the migrant student scenario, no one suggested that the student should continue to use his or her L1 for study in parallel with learning Italian. Either it would have been very easy to find study material in English or to encourage the use of translators. It would also have been possible to activate the Albanian-speaking community in the wider society or to look for other Albanian or English-speaking students in the school or in similar schools. We therefore argue that teachers should promote the use of the L1, namely the minority language, for learning.

The model suggested by Cummins (1996) serves as a foundation for considering how first-language (L1) proficiency might be seen as significantly facilitating the acquisition of a second language (L2). He claims that a shared underlying skill across languages allows for positive transfer if a L2 is sufficiently exposed to and motivated to learn it. This suggests that transfer will only happen if learners are proficient in their L1, if they receive adequate input in L2, and if they are motivated to acquire that language (Holzinger & Fellinger, 2014; Knoors & Marschark, 2014). Cummins distinguishes between fundamental academic and interpersonal communication skills and broad cognitive language abilities. Academic language skills include broad cognitive language skills as well as language-related problem-solving abilities and literacy abilities. Based on interdependence theory, this fundamental cognitive and academic competency is universal across languages, allowing for the transfer of shared higher-level language and literacy-related skills (Holzinger & Fellinger, 2014). This hypothesis thus suggests that proficiency in a home language will result in a higher level of conceptual and linguistic proficiency as well as literacy in the second language (L2).

Literature further suggests some strategies and adjustments that teachers can practise to promote native language use and the attitude of appreciation of all languages through context. About promoting L1 use, some authors suggest that encouraging Child Language Brokering (Pugliese, 2016) improves academic results, as well as encouraging students talking at home about academic topics (Andorno-Sordella, 2021). Other strategies that are widely used for this purpose are Translanguaging (Cioè-Peña, 2017) and Intercomprehension (Wei, 2023).

Intercomprehension and translanguaging (see Section 2) are two concepts that deal with interaction and comprehension between different languages but differ in their approaches and goals. In contrast to translanguaging, inter-comprehension is a concept that refers to the ability to understand and communicate in a foreign language using knowledge of one or more similar or related languages. Individuals using inter-comprehension can recognise similar words, grammatical structures, and language patterns between languages, enabling them to understand and communicate effectively even if they are not fluent in the target language.

Enhancing minority languages beyond the classroom level

As it has been argued in the introduction of this section, when it comes to the enhancement of minority languages, the everyday reality in the classrooms around the world first and foremost depends on the language policy (Laakso et al., 2016). Even though, teacher’s actions and methods, their language-awareness and attitudes towards linguistic diversity improve learners’ access to their first language and their multilingual development and contribute to more inclusive school environments, the preconditions for doing so are dependent on measures and actions on a higher level. It is public authorities and educational planners who have a key responsibility in building the foundations that support linguistic diversity at an administrative level.

To make it more concrete, for instance, in the Scenario of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, changes on the macro-level (i.e., the organisation of the school system) might be necessary. A cross-linguistic “collaboration between policymakers, school authorities, school heads, and teacher training” (Gross, 2019: 159) and the creation of one single school system involving personnel from all three language groups could sustain the preparation for a multilingual society (Baur, 2000; Baur & Videsott, 2012). Another important step could be the adaption of the Ladin school model, the parity model, in which all official languages – minority and majority languages – do have their place and equal value. Further, teachers in these school’s act as role models since children encounter the teacher as a trilingual person able to switch from and to each of the three languages since all teachers at Ladin schools have to document their knowledge in all three languages (Risse & Franceschini, 2016).

Another concrete example for possibilities of action on a higher level applies to Scenario 1, the case of Jenna. Around the world and in Europe interpreter services for sign languages vary even though interpreting services are crucial for accessibility as it enables the learner to know what is discussed in the classroom and what the teacher is teaching in the spoken language. Providing interpreting in the educational setting, thus, promotes linguistic accessibility in the learning environment. The World Federation of the Deaf has estimated that 90% of deaf children do not have access to education (Haualand & Allen, 2009). Out of those 10% who have access to education, only a small minority, receives bilingual education where a signed language is used. Communities using signed languages, called as deaf communities, embody a rich Deaf culture with different events, traditions, customs and values. These communities also provide spaces to learn a (national) signed language and build a Deaf identity. Thus, Deaf and sign language communities have valuable knowledge, Deaf-centred ontologies and views of social inclusion (Snoddon, 2020) to share with community members and others. Collaborating with the wider community would therefore be one possibility of action going beyond the classroom level. Teachers and schools can work with local language communities to create spaces where people from minority languages and cultures can meet and teach each other.

Finally, the enhancement of minority languages in educational contexts might be reached also through a higher degree of diversity within the teaching staff. It would be important that linguistic minorities are represented also among the teaching staff, not only among the students. Empirical data of the European Commission (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023) show that diversity in the teacher population is still quite uncommon in most European countries. Only few European countries do have policies and measures for increasing diversity in the teacher population and these are mostly restricted to the facets of disability and migrant backgrounds (for example, through specific quotas reserved for people with disabilities in the public sector). So, on the one hand we have an increasingly diverse student population and on the other hand a still quite homogeneous teacher population (Bellacicco & Demo, 2022; Bellacicco et al., 2022), even though research was able to show the positive effects of a diverse teacher workforce, for example role model effects (Goldhaber et al., 2019). Furthermore, dating back to 1994, international agendas asked for a diversification of the teacher population as being a right of students with special educational needs (UN CRPD, 2016; UNESCO, 1994). But why would it be important to have teachers who are minority language speakers in the schools? This possibility for action can be applied to all four scenarios. Jenna, for instance, would encounter a teacher who is deaf or fluent in a national sign language and knows about specific didactical strategies making education accessible to her, acts as a role model, (i.e. self-empowerment, self-advocacy, autobiography), deals openly with the disability and the fact of being a member of a minority language group, who understands Jenna emotionally (Bellacicco et al., 2022). This would not only have a positive impact on Jenna but for all children in the classroom. Very similar positive outcomes can be expected for Enson and Elina if in their classroom there would be a teacher of their same linguistic community. For Giulio’s case, options of action might be slightly different since the presence of the minority language teachers in the school has already been established but is apparently not sufficient to make the context inclusive. Instead, a closer collaboration between the Italian speaking subject teachers and the L2-German teacher would be necessary to reach a further level of inclusion (for example, co-teaching and bilingual lessons; content integrated language learning [CLIL] where teachers of both or all three languages are involved).

Closing remarks

Human communication varies widely, showing up in the many linguistic families, the wide range of dialects and registers within each community but also in the diverse communication practices among different actors, contexts, and time points (Blommaert, 2010). Therefore, it seems clear that “diversity is an inherent feature of the phenomenon of language” whereby the latter can play a powerful role in creating and reinforcing social inequalities (de Korne, 2021), such as when children and adolescents who are minority language users are disadvantaged in educational contexts (Heller & Martin-Jones, 2001). Due to restricted time and resources very often, it is decided to only give space to specific languages without considering what would be an effective contribution to the learners’ well-being and social equality (de Korne, 2021). For decades, there have been criticisms that education systems have failed to support minority language learners. As teachers, we must be particularly careful to ensure that the use and development of all languages is actually supported, since these issues are linked to democracy, linguistic and minority, but more generally, to human rights and sustainable development. Even though language is mostly absent and invisible in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Fettes, 2023), according to Tonkin (2023), it is a key issue and affects human rights and (e)quality of education. Therefore, “if we wish to unite humanity around a common goal, we must first address the need for effective and inclusive communication: talking is of no avail if it is not accompanied by understanding – and understanding will not lead to action if it is unaccompanied by persuasion. Persuasion implies listening, because our common future requires consensus” (Tonkin, 2023: 3).

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Investigate and describe a scenario in your community/country that may be similar or vastly different from those depicted in this chapter.

- Describe the policies/laws that underpin your scenario.

- What works well in your scenario and what does not?

- What possible strategies do you suggest to enhance the learning environment for the learner(s) in your scenario?