Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

Working within Multidisciplinary Teams

Alexandra Anton; Ann-Kathrin Arndt; Miriam Sonntag; Beausetha Juhetha Bruwer; Miriam Cuccu; and Lydia Murphy

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

Multidisciplinary teamwork is complex and varies in different constellations and contexts. To give you an impression of multidisciplinary teams in different early years and school context, we provide four short example cases. To engage with the complexities, we provide more information for two cases later in the chapter.

Example Case 1: Multidisciplinary Teams in the Finnish Early Childhood and Care (ECEC)

When I first visited a Finnish daycare, I was amazed by the diversity of professionals involved in educating and caring for small children compared to what I knew from the Romanian school system.

The moment I stepped into the teachers’ lounge that morning, I knew something important was happening. In a separate area, away from the noisy group moving in and out in the morning rush, several adults were seated around a table. I couldn’t hear what was discussed, and even if I could, my lack of the Finnish language would have impeded me from understanding anything. However, that didn’t stop me from asking another teacher not involved in the discussion what that was about. I then found out that in Finland each child receives the needed support based on their assessment and individual learning plan created by the kindergarten teacher in collaboration with the family at the beginning of the school year. Their plan is revisited and adjusted throughout the year, according to the developmental milestones achieved, and travels with the child throughout the early years and in the transition from early years to preschool and school. Considering the diverse and complex needs of young children when they arrive in daycare, the ECEC team is informed about the trajectory of each child before the age of 3.

When things don’t go according to plan, multidisciplinary teams usually gather and give each other an update on the child’s progress, renew the existing goals, exchange insights, provide recommendations and inputs on related services or modifications to be tried out in the following weeks or months.

Are you interested in learning more about how Finnish early childhood and care is multidisciplinary by design? Take a closer look! (See section “A closer look on Example Case 1”)

Example Case 2: Early Learning and Care [ELC] in the Irish Context

Every morning, we met this little person at the school gate. They clung to their primary carer, arms tightly wrapped around their neck and their legs similarly around the waist. Acknowledging “You are so snuggly and warm around them.” They replied “My little koala bear.” The educator also acknowledged “It’s hard to leave them in the morning.” This little person would move from their primary carer’s arms to the educator, squeezing them just as tight. Upon entering the classroom, it was loud, and busy, with active children all engaged in play. When the educator was putting them back down on the ground, they could see their eyes darting from side to side. The little person would then rest their head on the educator’s stomach ‘they were too tired for school; they wanted to go home’.

This little person was struggling with the level of noise in the classroom. At times, they would seek rest from the overstimulating classroom by putting the educator’s hands over their ears or leaning really close to their key person to seek rest. From our training and reflective conversation and from the groundwork with the team members we decided to turn an unused art room into a ‘nurture nook’ for this little person to have comfort and safety from the busy room when needed. An unintended result of this room change meant all the children had more space which made the room less noisy for everyone. This room was equipped with a sliding door the children could open and close depending on their needs. It was used as a place for peer-to-peer and adult/ child communication, story-time and/or a place for the children to have private conversations with educators or with other children. We received funding from an external agency to equip this room with weighted blankets, ear defenders, and speakers to play soft music intermittently. The children added teddy bears to it for comfort.

While this little person started to arrive earlier to school, and their attendance improved, possibly because they were able to transition to school using this room to acclimatise themselves to the bigger group in the morning and throughout the day. Still, school could be a real challenge for this little person. With consultation with their primary carer, we sought outside multidisciplinary support from the Access and Inclusion Model (AIM) to ascertain supportive strategies when they were changing clothing from inside to outside and strategies for dealing with peer relationships. Their primary carer also accessed support from the multidisciplinary primary care team with Ireland’s Health Service Executives (HSE). However, due to COVID-19 and an extremely long waiting list, an appointment was not available before he transitioned to primary school. Nonetheless, using an inclusive, relational approach in our education setting, linking in with the Access and Inclusion Programme, and with the support of their primary carer this little person’s strengths-based progress was able to continue with them to primary school.

Example Case 3: Supervision in the Italian Context

Teachers usually perceive their daily routine as overwhelmed with meetings and bureaucratic commitments. They often do not have time to reflect together on their practices, or to talk deeply about the students.

Within the Labs to Learn project (https://labstolearn.it/) aimed at minors in the Piedmont region (Italy) to combat school dropout rates and prevent educational poverty, a monthly supervision for teachers was part of the action Study Method.

Study Method was dedicated to the first-year classes in lower secondary school, so that each child could find “made-to-measure” strategies, considering individual differences, strengths and learning styles (Stenberg, 1998), thereby strengthening perceptions of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1994) connected to school. The supervision, aimed at each class council, guaranteed a space to reflect and talk about challenges connected with the experimentation of personalised study methods in the classroom.

The meetings allowed them to talk about emotions connected with working in the classroom, during and after the pandemic. Throughout the meetings, teachers shared their fears about how to deal with interruptions of the lessons due to the lockdown. They had time to share impressions of each student (beyond marks), including those who have needs that they cannot express clearly. All points of view contributed to a holistic understanding of the students. This approach helped to work on the group dynamics, to generate a sense of togetherness and to find common strategies for a better classroom management.

Example Case 4: Primary School/Pedagogical Counselling Centre in the Austrian Context

Patrick, a boy in the second year of primary school, has difficulty following the lessons and his academic performance does not meet the expectations of the curriculum standards for primary school. The class teacher, who is young and in general ready for open lessons, feels overwhelmed by the “heterogeneity of the learning group” to respond to Patrick’s individual needs within the framework of regular lessons. Talks with the parent or guardian fail, appointments are not kept. Patrick often comes to school with clothes that are not suitable for the weather or without breakfast. He seems neglected and often consumes media that are not appropriate for his age, has access to game consoles etc. and often attracts attention through aggressive behaviour. As the head of the Pedagogical counselling centre at the time, I got to read Patrick’s special educational needs assessment during the procedure for determining special educational needs. (PBZ, later Departments of Inclusion, Diversity, and Special Education, FIDS, see Key aspect 3)

It clearly states that Patrick does not show any signs of a disability, but due to his difficult environment and his persistently weak performance at school, he should be given special educational needs for the general special school (learning focus). Instead of assigning him Special educational needs, I worked with the head teacher, the class teacher in charge and a counselling teacher who was temporarily present on site to find out which support system Patrick needs to reduce his barriers to learning and development. We were guided by the following questions, among others:

- What interventions can be made in the classroom?

- What personnel resources can the school authorities provide in the short term to enable the class teacher to teach in a more open and differentiated way as a team?

- What extracurricular institutions and contact persons are there that can provide relief and support for Patrick’s home environment?

- How can the guidance counsellor use her resources profitably for Patrick and the class teacher? Which competencies should be developed within the class?

Concrete steps were planned, a support system was established inside and outside the school in close co-operation with the school supervision and the guardians, and the SEN (Special Educational Needs) procedure was paused for the time being. Patrick was able to develop positively over the next few months: both his school performance and social behaviour were able to stabilise, the class teacher felt relieved, and the counselling teacher repeatedly reported a positive course of development – for the entire system. As a result, the SPF procedure could be dropped after about half a year and Patrick’s barriers could be significantly reduced by establishing a support system without having to receive a stigmatising label.

If you want to know more about the Austrian Departments of Inclusion, Diversity, and Special Education (FIDS), see subsection: Support structures on regional level.

Initial questions

Think about your experiences in educational institutions like kindergarten or school. Apart from your own school days, you might think about your observations during school visits or your experiences during internships or practical phases within your initial teacher education. Furthermore, some of you might have previous or current experiences of working in kindergarten or schools:

- Who is part of the multidisciplinary team in this context?

- What could be the difficulties of working in a multidisciplinary team?

- What are the benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork?

- What practices contribute to positive multidisciplinary teamwork experiences?

Introduction to Topic

“I”-Perspective

Picture a teacher sitting at home thinking:

“Oh, but I was not trained for that (new situation or challenge) …. I don’t have enough time (to discuss it with someone else in the professional team) … I don’t want/find it hard to work with (other professionals)… I don’t know how to deal with this situation…”

The above thoughts depict teachers struggling with a certain situation in the classroom, but not feeling prepared to deal with it properly, not thinking that the training or previous experience helps in any way and not being willing to cooperate with other professionals within and outside the educational setting. When reading the thoughts above, they may sound familiar to you, as these thoughts are common to all teachers, irrespective of whether they are new in the profession or already highly experienced. We are going to examine in closer detail four scenarios that depict different cultural contexts and grade levels that may help you think about the topic differently. These scenarios will be accompanied by the specific working conditions that underpin the connections and dynamics between the members of the multidisciplinary teams. The realities of each of the contexts within which the educators and other professionals of these scenarios (Example Case 1-4) find themselves will be discussed. Throughout the chapter there are reflection questions for the reader to pause and reflect on the section just read. These are highlighted similar to the reflective question below.

What can teachers do when they do not know how to deal with a situation?

Firstly, let’s establish that it is normal to have these different thoughts and feelings. Secondly, teachers do not need to work on their own; they do not have to be a lonesome player, although this was common in schools for a long time and in many cases still is (Terhart & Klieme, 2006).

Aiming for an inclusive school system changes the perspective completely: every class is a diverse learning group with diverse needs, and it is normal to look for a wide range of competences and professions (Booth & Ainscow, 2019).

For one person it is overwhelming to identify and overcome barriers of learning and to respond individually to the diverse needs of all students. Whether you are a new teacher or have years of experience, there will always be challenging and new situations. You cannot manage it alone, there is a need for certain support, there is a need for a team (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022). If that team is multidisciplinary, it is even better, because then you have a huge variety of knowledge within the team. It is important for teachers to collaborate in the classroom and school community because you will find new and proper solutions when you have other educators, other experts, other views, other perspectives and competences to communicate with (Ahlgrimm, 2021).

Teachers often do not know about the opportunities for collaboration that exist in and outside their school. As a teacher, when you do not know how to deal with a situation, you can look for a team to solve it. You can ask colleagues, your team-teaching partner, relevant actors and other professionals. You can also ask your principal if there are any experts on the situation you are experiencing already in the school. Also, you can seek support from institutions outside your school. There are several support systems established to answer questions, queries, challenges that you might experience. Therefore, it is a competence to ask for advice.

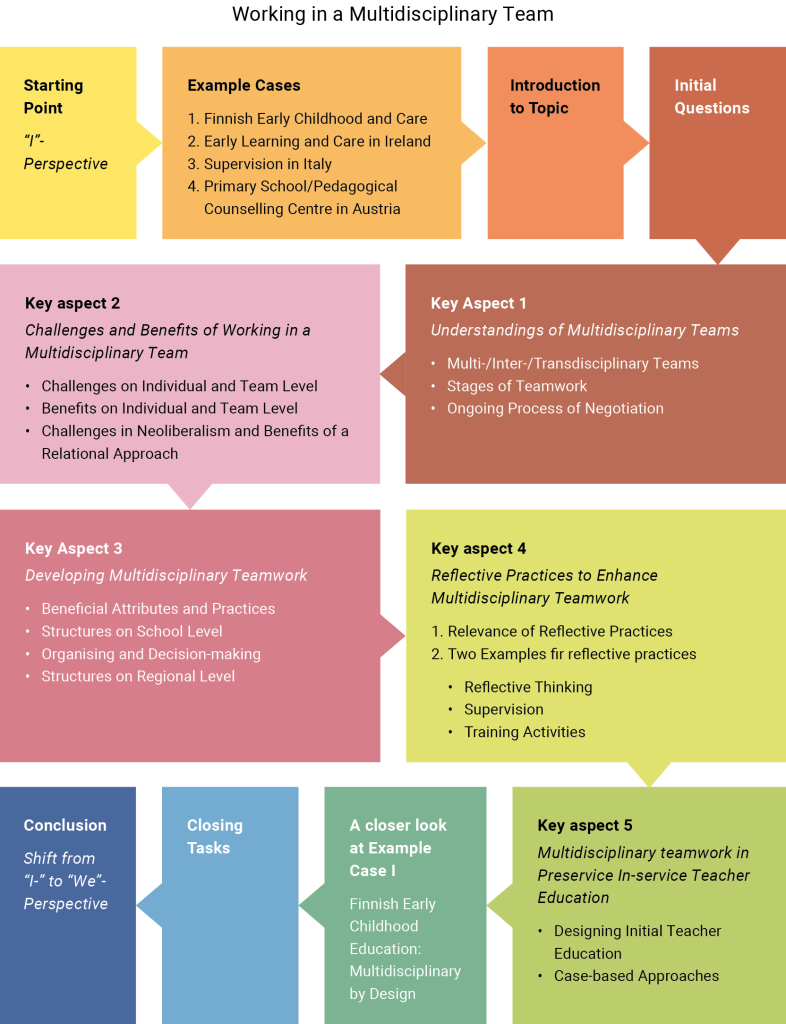

Our starting point refers to the “I”-perspective. In this chapter, we focus on five key aspects: Key aspect 1 refers to understandings of multidisciplinary teams based on a differentiation between multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary teams, stages of teamwork and understanding multidisciplinary teamwork as an ongoing process of negotiation. Key aspect 3 draws on the challenges and benefits of working in a multidisciplinary team on individual and team level and refers to challenges arising from the wider context of neoliberalism and the benefits of relational approaches. Key aspect 3 refers to developing multidisciplinary teamwork by considering beneficial attributes and practices, structures on school level, organising and decision-making as well as structures on regional level. Key aspect 4 highlights reflective practices to enhance multidisciplinary teamwork by summarising the relevance of reflective practices and providing two examples for reflective practices. Key aspect 5 focuses on multidisciplinary teamwork in pre-service and in-service teacher education by referring to designing initial teacher education and case-based approaches. After these five key aspects, we provide “a closer look” at example case 1 to learn how Finnish early childhood education is multidisciplinary by design. In the end, we provide closing tasks and a conclusion which emphasises a shift from “I”- to “We-”perspective.

Figure 1: Overview of the Chapter (own figure)

Key aspects

Key Aspect 1: Understandings of Multidisciplinary Teams

There are various understandings of multidisciplinary teams. For example, in some contexts, it would be more likely that we would talk about multiprofessional teamwork. Hence, different terms might be used depending on the particular context. At the same time, terms are often used interchangeably. For simplicity, we use multidisciplinary team in this chapter to refer to different constellations, intensities, and contexts. Knowing and reflecting about different terms is useful to reach a common understanding.

Let’s start, by briefly looking at “team” and “teamwork”: A team is a group of individuals with a shared understanding of interdependence, the necessity for communication, and the value of teamwork who have been organised for a specific goal. Teamwork is the interaction that is demonstrated in the information sharing between team members, which assures the synchronisation, coherence of the pace and rhythm of collaborative activities and results in the effective operation of the entire team and a high level of individual commitment (Volkova et al., 2021). At the same time, team constellations working together can differ regarding the intensities of teamwork, goals, and context as pointed out by the conceptual model “Multi-/inter-/transdisciplinary teams”.

Differences between Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinary Teams

Starting from the basic questions of who works with whom with which goal, Friend and Cook (2010: 65) refer to multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams as three different models of team interaction.

These differ concerning the “philosophy of team interaction” (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65): How do members understand themselves? In multidisciplinary teams, members value the importance of contribution of different professional groups or disciplines, but their “services remain independent” (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65). An example of this would be when teachers work together with professionals outside school, for example physical therapists. In interdisciplinary teams, members share their responsibilities, however, each professional group remains “primarily responsible” for their tasks (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65). For example, in German or Austrian in whole day schools, there is often an institutional distinction between teachers who mostly teach their lessons before the lunch break and educators who are responsible for various activities in the afternoon. While teachers and educators might not teach together, they might, for example, develop a shared individual educational plan. In transdisciplinaryteams, members work together “across disciplines” and learn from one another (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65). On the classroom level, co-teaching of classroom or subject teachers with special educators or other specialists is an essential approach for inclusive schools. In one school in Namibia, an English teacher and a sign language teacher co-taught to facilitate English language learning helping all students to understand English better. In Finish early childhood education and care, several professionals like kindergarten teachers, social welfare workers, childcare workers, and special education teachers – to name but a few – are involved in a child-centred task together.

Multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams differ in the way they communicate (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65): Multidisciplinary teams share information about their independent work, for example, on assessment, and develop separate education or service plans. Ininterdisciplinary teams, members meet on a regular basis, for example, in case conferences, and combine their goals for a single individual education plan. In a transdisciplinary team, regular team meetings for both sharing information and learning from each other are crucial. This allows them, for example, to assess collaboratively and develop an individual education plan together.

Besides the “role of the family” (Friend & Cook, 2010: 65) varies: In multidisciplinary teams, families meet with each professional group separately. In interdisciplinary teams, families meet with all the team members, but these report independently. In transdisciplinary teams, families are more involved in these joint meetings.

Think of your own experiences in educational institutions. How can you relate these experiences to the model of multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams? What’s important for team interaction in your particular context?

This differentiation between multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams supports thinking about the intensity, goals, and context of working together. Even if different terms like multiprofessional team are more commonly used in your context, differentiating between multi-, inter- and transdisciplinary teams helps you to understand your own team better and find starting points for future development. As mentioned in the beginning, we use multidisciplinary team in this chapter to refer to different constellations, intensities and contexts.

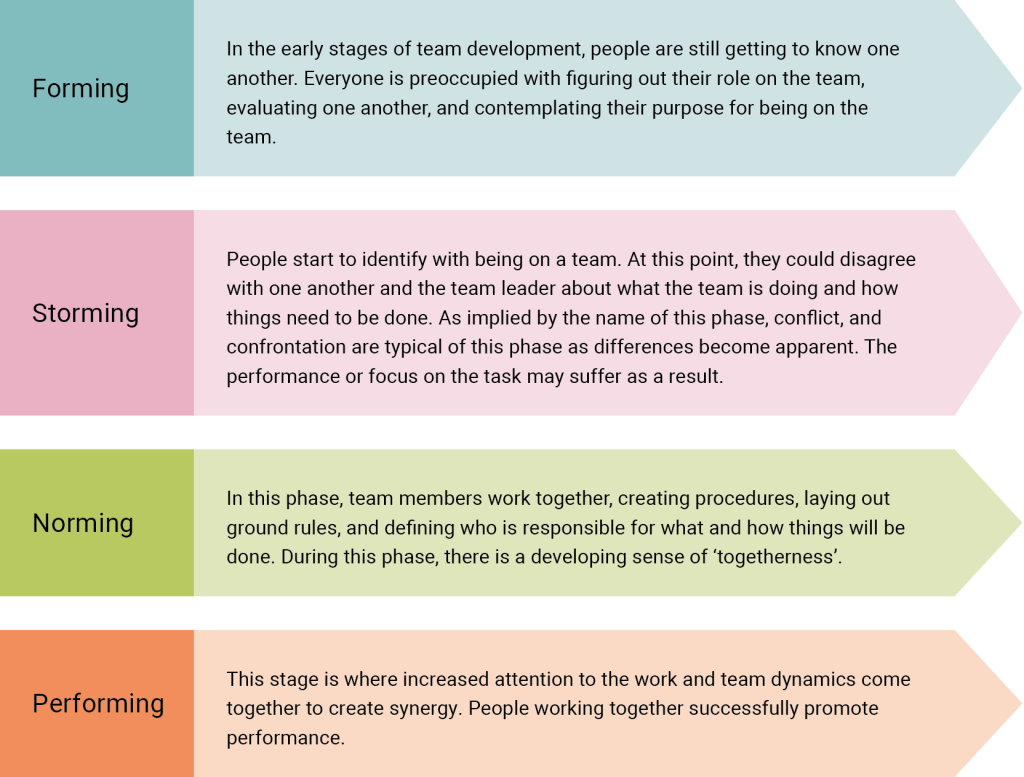

Stages of Teamwork according to Tuckman

Another differentiation which is also helpful to understand different constellations of multidisciplinary teams, looks at the development of the teams: Dugang (2020) describes Tuckman’s model as a significant method to understand the evolution of teamwork. This model acknowledges that teams do not initially exist in a fully developed and functional state. The model proposes that teams develop through a series of distinct phases, from their inception as loosely connected teams of individuals through their development as cohesive teams with a clear purpose. According to this model, as discussed by Dugang (2020), there are four stages to teamwork that include:

Figure 2: Stages of Teamwork According to Tuckman

Multidisciplinary Teamwork as an Ongoing Process of Negotiating Roles and Responsibilities

Multidisciplinary teams are considered as a reaction to (increasing) complexities (Easen, Atkins & Dyson, 2000). At the same time, multidisciplinary teamwork is not a “quick-fix” (Nichols et al., 2010). Hence, it is important to take the complexities of multidisciplinary teamwork into account. Bauer (2014) suggests a process-oriented perspective on multidisciplinary teamwork: in our initial questions we ask who – which professional or occupational group – is part of a multidisciplinary team. Instead of thinking about these professions or groups as unchanging/unchangeable and self-contained, Bauer (2014) emphasises that collaboration takes place

“between professional actors who continuously have to define and negotiate their specific tasks, responsibilities and abilities, trying to come to terms with each other and sometimes also bargaining against each other. In this process, boundaries between professional groups shift, new tasks and responsibilities emerge and are distributed and assigned” (Bauer, 2014: 274).

This process-oriented perspective refers to the theoretical concept Negotiated Order(ing) by Strauss et al. (1981) which highlights how professionals negotiate their tasks and division of labour. This includes – for example, when new staff members join the team or when new conceptual frameworks or technologies become relevant in a certain field – renegotiating tasks and responsibilities. Overall, (re)negotiation between different professionals stabilises or, at least in the long term, might also change social order (Strauss, 1978). For understanding multidisciplinary teamwork, this raises the important question: what is perceived as (non) negotiable by whom? (Strauss, 1978: 252). In this regard, it’s fruitful to pay attention to ways multidisciplinary teamwork is situated (Clarke, 2005), for instance, in different national and local school contexts (Arndt, 2022; Hansen et al., 2020; Naraian, 2010).

Based on an ethnographic study on multidisciplinary teamwork in Swiss primary education, Kosorok Labhart and Maeder (2016) highlight, that planning and clarifying one’s roles and responsibilities is part of the continuous negotiation. Overall, understanding multidisciplinary teamwork as an ongoing process enables a change of perspective by not focusing solely on the individual teacher and, for instance, their (lacking) willingness to collaborate, as it is often the case in discussions on multidisciplinary teamwork.

Key Aspect 2: Challenges and Benefits of Working in a Multidisciplinary Team

Teamwork amongst role players is crucial to develop inclusive schools, which involves all school systems. The inclusive school community places teamwork at its core, and it is a key strategy for assisting all participants in such a community. This suggests that no teacher, parent, education support worker, student, or volunteer should have to handle significant challenges by themselves. Successful inclusive education is built on support. The focus of inclusive classrooms and schools is on how to run them as loving and supportive environments where a sense of belonging is developed and everyone feels accepted, encouraged, and cared for by everyone else in the school community (Swarts & Pettipher, 2016).

However, interacting with other people can sometimes be hard. Each one of us has our own personality, character, way of communicating, and habits, and it can be difficult to engage with people who are different from us. However, by working closely with people with different skills from yours, you not only have the unique opportunity to learn something completely new every day but also transfer to others some of your own knowledge. You can learn from other people’s experiences things that you would not be able to find in books, or that would probably take you a long time to learn on your own (Pinti, 2018).

It is important to address challenges and benefits of working in a multidisciplinary team. We take a two-fold approach: First, we take a closer look at common difficulties and benefits on individual and team level:

- Why is it sometimes difficult to work in a multidisciplinary team?

- Why is it worth it to work in a multidisciplinary team?

After this, we situate challenges of multidisciplinary teamwork in the broader context by focusing on tensions arising in education in neoliberalism, especially with regard to the so called ‘hidden curriculum’. In this respect, relational pedagogy can form an important approach to critically reflect on these tensions.

Challenges on Individual and Team Level

Working in a multidisciplinary team might be challenging, both at an individual and at a team level. When faced with difficult situations, your first reaction could be to think that it is your sole responsibility to solve it, that it is faster to do it on your own, or that it is less messy, and so asking for help does not come easily.

| Challenges at the individual level |

| ● When you see your profession as isolated, at the same time you acknowledge that a different set of skills is needed to respond to the complex situations you encounter in your classroom (Bauer, 2014; Pölkki & Vornanen, 2016).

● For this reason, it can be hard to fully trust other professionals (Ekins, 2015). ● You even rank your and others’ input and opinions according to a certain hierarchy, and based on their level of qualification, you might see yourself or others as more or less entitled to contribute to the common effort (Hood, 2015). ● You can be blinded by the human ego, which stops you from seeing the common good that a team can achieve (Herbert & Broomfield, 2019). |

| Challenges at the team level |

| ● Finding enough resources and the right competencies needed to tackle a situation, and finding the right professionals at the right time can be tough (Unabhängiger Monitoringausschuss der Republik Österreich [UMA], 2023).

● Or even beginning to consider that other professionals in the same school or in the close community might help, can be exceptional (Solvason & Winwood, 2022). ● Collaborating across institutional boundaries can surge the challenges. Without having or designing operating models, guides and procedures, it can be problematic to find common grounds or reach agreements and communicate important information (Behringer & Höfer, 2005). |

Benefits of Individual and Team Level

It most certainly is worth working in a multidisciplinary team. Just like with the challenges, the benefits of working in a multidisciplinary team can be identified at both the individual and the team levels.

| Benefits at the individual level |

| ● Not feeling like we are the lone warriors helps us have a broader perspective, helps us respond to the needs of our students better and feels a sense of accomplishment about our work.

● Strengthening our communication skills, becoming more empathic, and being willing to adopt other perspectives will help us build more trusting networks and achieve effective cooperation (Kumpulainen, 2013). ● By working closely with people with different skills from yours, you not only have the unique opportunity to learn something completely new every day but also transfer some of your own knowledge to others. You can learn from other people’s experiences things that you would not be able to find in books, or that would probably take you a long time to learn on your own (Pinti, 2018). Working in a multidisciplinary team shifts the boundaries of individual professions, and adds in new tasks and areas of responsibility, which helps us become more flexible and adaptable; instead of the “everyone does everything” type of culture, there is more clarity in our roles and responsibilities (Bauer, 2014; Onnismaa, 2017). |

| Benefits at the team level |

| ● When working together in a multidisciplinary team, educators and other professionals exchange information and perspectives about our students, which can do better justice to them and contribute to our commitment to inclusive education (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022).

● As multidisciplinary team members who develop joint solutions to challenges, we learn from and with each other, and by strengthening our professional actions our workload decreases (Ahlgrimm, 2021). ● To provide adequate support to students who face learning obstacles, it is important that all role players in the learning process cooperate and help one another. To do this, it is essential to value each person’s knowledge, abilities, and experience while also promoting their engagement and involvement. This calls for collaboration between each and every teacher as well as between educators and other stakeholders in general. In a team that works together, fostering an environment of trust, openness, and dedication needs to be a core rule. Due to the nature of true professional barriers being crossed, this type of collaboration can be referred to as transdisciplinary teamwork (see models of team interaction). |

Reflect on your own experiences of working in a group or with a team. Alternatively, you can also reflect on a situation which you observed, for example, during a classroom visit.

What challenges did you perceive – or observe – on an individual level and on the team level?

What were the benefits of working in a team on an individual level and team level?

Challenges in the Context of Neoliberalism and Benefits of a Relational Approach

While we focused on challenges and benefits on individual and team levels before, next we take a closer look at challenges of multidisciplinary teamwork arising from teachers’ role as ‘lonesome players’ by situating this in the broader educational and societal context influenced by neoliberalism. Today, education is still mostly operating based on a confirmative-based ecology to produce the long-term outcomes of an equitable workforce (Öchsner & Murray, 2019). Neoliberal policy in teacher education is creating a competitive environment stressing the sole interest of an I-focus rather than a We-culture. Thus, eroding a collegial environment promotes teachers’ agency to make decisions and problem-solve. By quantifying (measuring) educators’ performance and steering an environment of competition over the connection, teachers can be in the space of feeling vulnerable in their work with colleagues, learners and their families. Ljungblad (2021) suggests teachers are finding it really difficult to use pedagogical tact (intuition) when powerful neoliberal agendas – reflected, for example, in policy documents stressing ‘efficient’, ‘effective’, ‘standards’,’ tools’ – are at play.

To put the above literature into context, focusing on classroom-based education and changes to policy strategies, we could possibly unpack the nested paradoxes that can be layered in professionalisation, for example, leading to greater emphasis on hierarchies—a major challenge for working in multidisciplinary teams. Let us take a look at current development in the Irish early education system seeking to professionalize a newly constructed degree-led profession.

New degree-led profession, new hierarchies in multidisciplinary teams?

Currently, Ireland’s Early Learning and Care sector is going through a huge amount of change whilst the leaders are trying to professionalise the sector. The implications of these changes have not been all negative, for example, the under three’s now have a voice and are being seen, this is welcomed by most in the sector. However, one of the paradoxes within the Irish context is the government’s strategy to professionalize the early years sector by implementing a tiered pay scale for managers and deputy managers running a play school. Also, there was a structured minimum regulated wages requirement for early years educators depending on your level of qualification. By introducing funded pay scales this then establishes a hierarchical classroom by promoting one degree graduate to become the classroom’s lead educator. Moreover, moving away from a co-teaching structure to now embed a ranked system in our early years classroom (Nurturing Skills, 2021).

The Irish ELC sector has only recently had an influx of degree-led graduates, many educators with vocational qualifications but twenty to thirty years’ experience could not apply for the lead educator positions as they did not have the academic qualifications for the position.

What are the unintended consequences of this decision?

How could an understanding of teamwork be evoked in this situation?

Hierarchies can also be linked to the so called “hidden curriculum” which – in contrast to valuing multiple perspectives in a multidisciplinary team – emphasises certain perspectives: Dean, Roberts, and Perry (2023) admit that neoliberalism has caused a ‘curriculum hierarchy’ or/and the ‘narrowing of curriculum’ meaning subjects such as Literacy, Numeracy, and Scientific knowledge are seen as superior or more valuable in the education system because they can be measured. The ramification of this narrowing is effectively changing the teachers’ role and identity.

An example below is looking at educational inequality from the Australian context.

Resources for multidisciplinary teams in the context of educational inequality in Australia:

Sahlberg (2011) states this marketisation policy of education falls under the Global Education Reform Movement (or GERM) allowing parents to put pressure on the school system to produce academic outcomes. Australians are noticing educational inequalities from the marketisation of education particularly in learners in vulnerable backgrounds (Dean, Roberts & Perry, 2023). Public funding is being used to fund and resource private education in Australia. Making sure learners attending private school have access to multidisciplinary teams and private educational supports causing a disparity between teachers working in public schools because of underfunding and being under-resourced having a knock-on effect for teachers and what education looks like for these schools. Paving a bigger divide of educational, career opportunities, and inequity for the future of more impoverished families. Perry and Southwell (2014) conducted a study on the effects of socio-economic status on education and found that learners from more impoverished backgrounds had less opportunities for curriculum diversity.

How does this system affect teacher education in Australia in working together?

Think about private schooling versus public schooling in your context, what are the differences, for example, concerning the resources and professional groups involved?

What other differences between schools (for example, special and inclusive schools, urban and rural schools) are relevant when it comes to resources, professional groups and (multi-) professionalism?

By way of example, this reflects the limitations of solely focusing on the school level and highlights the importance of considering the ‘ecologies’ of the multidisciplinary team (see for an ecosystemic perspective on teamwork: → Chapter on teamwork in the classroom).

At the same time, these challenges arising from neoliberalism, highlight the importance of Relational approaches to look beyond measures and focus on a We-Perspective. Relational approaches emphasise the importance of the ‘whole’ learner and their families, working in connection instead of competition for greater opportunities for diverse learners and communities. Through critical thinking, decision making and problem-solving, university educators are trying to tackle some of the tensions between collegial workplaces in communities and sole interest learners (Rodriguez, 2017). Teachers and learners are engaging in relationships all day long making split-second decisions throughout the day. Educators (in training) may at times possibly have a feeling of unease within themselves to conform to academic structures or they may have a feeling of pressure to implement strategies that go against their living values.

Ljungblad (2022) suggests the answer to this problem is the reciprocity of relationships. Knowing these values and beliefs are ever evolving regardless of how long you are in education. Thus, teacher education and third level education play an important role for the ideal of growing and flourishing (Wojciechowska, 2022) which can support the aforementioned benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork on individual and team level.

Key Aspect 3: Developing Multidisciplinary Teamwork

Multidisciplinary teams with members who understand how to learn from shared experience will be the most productive. The different points of view of the team members should complement one another. It is necessary to select team members wisely because, in addition to practical expertise and a problem-solving perspective, effective teamwork also necessitates collaboration and soft skills.

Attributes and Practices to Motivate Positive Multidisciplinary Teamwork

Literature correspondingly provides several attributes that motivate positive multidisciplinary teamwork. Many of these have been consistently repeated, and some are overlapping (Engelbrecht & Hay, 2018; Pinti, 2018; Tarricone & Luca, 2002). Noteworthy attributes and practices that were identified to motivate positive multidisciplinary team experiences are:

- Open communication and positive feedback

A productive work environment is facilitated by attentively listening to team members’ needs and concerns, recognising their contributions, and expressing appreciation for them. Members of the team should be prepared to offer and accept constructive criticism as well as give honest feedback. - Commitment to team success and shared goals

Team members have a commitment to the project’s success as well as to the team’s success. Successful teams aspire to achieve at the highest level and are highly motivated. - Interdependence

Team members must foster an environment where their combined contributions will be much greater than their individual ones. The team can accomplish its objectives at a much higher level when there is a positive, interdependent team atmosphere. - Interpersonal skills

The capacity to be open and honest with team members, to be dependable and supportive, and to respect the team and its members as individuals. It is important to encourage a compassionate work atmosphere, which includes the capacity for productive teamwork. - Commitment to team processes, leadership, and accountability

Members of the team must take responsibility for their contributions to the team and the project. They must understand team procedures, best practices, and fresh concepts. For a team to succeed, including in shared decision-making and problem-solving, effective leadership is important. - Equality

Members should actively seek to ensure that all other members feel equally empowered in their potential to positively affect results and should all experience an equal sense of equality in decision-making. - Trust

Members should have confidence in the dependability or trustworthiness of the strength, skill, and character of their fellow members. To build reciprocal participatory and collaborative development, interpersonal trust elements such as character trust, competence trust, and communication trust are essential. - Respect and Cultural Sensitivity

Members must honour one another and act and speak in a way that shows that respect. This calls for introspection and awareness of one’s own belief systems, as well as an investigation of one’s own comprehension of and respect for other people’s belief systems. - Modesty

Being modest does not require you to minimise your abilities, your job, or yourself. It suggests that while you should be happy with your achievements and recognise your talents, you should not constantly and incessantly boast about yourself or believe that you are superior to others. Recognise both your strengths and your flaws. We are always learning because knowledge is endless. It is highly possible that you will drive your team members away if they think of you as a haughty, conceited person with a big ego who brags, feels superior to others, and has a showy personality. This could have an effect on team communication, making it uncomfortable for your team members to bring up fresh ideas and problems with you. As a result, the success of the team will be hampered. - Open-mindedness

Respect others’ thoughts and give them a sincere ear. Key elements of successful teamwork include meetings, talks, and brainstorming sessions. You need to put the other team members in the same position as you to share and discuss fresh ideas and challenges to find answers and make choices. Do not mock the ideas of others. Allow everyone to speak, listen, maintain composure, and wait to interject until they are through. The success of the team depends on everyone learning and sharing new things, but it also benefits you personally and broadens your knowledge. - Supportiveness

Ask for assistance and offer to assist. If any of your team members could benefit from your knowledge or experience, make the time to assist them. Offer to assist, even if it is just by checking over a team member’s text for errors or keeping an ear out while they practise their talk. Do not be hesitant to seek assistance if you are unable to handle a problem on your own. Of course, there needs to be a healthy balance. Try your best on your own before asking others to help. To build a peaceful work atmosphere, it is crucial that team members feel supported by one another and by the team as a whole. - Reliability

We often find ourselves working on certain project components in multidisciplinary or team projects based on our areas of expertise. This indicates that our work frequently depends on the work of others, and vice versa. Thus, it is crucial that we adhere to deadlines and complete our tasks on time. Regardless of how busy you are, make sure you finish your work as quickly as you can and that your colleagues can depend on you.

Furthermore, an appropriate team composition is crucial for developing multidisciplinary teams, which is linked to team members’ awareness of their unique roles and requirements. This leads us to take a closer look at the institutional level. For example, we focus on schools.

Creating Structures to Support Multidisciplinary Teamwork at the School Level

Collaboration between teachers and different professionals is considered “an essential part of successful inclusion” (Wallace et al., 2002: 350; see also De Vroey et al., 2015). At the same time – and the difficulties we mentioned above reflect this – it is a common misunderstanding or “myth” that professional collaboration “comes naturally” (Friend, 2000: 132). While this highlights the importance of addressing multidisciplinary teamwork in initial teacher education and continuous professional development (see key aspect 4), developing collaboration between teachers and other professionals can also be considered an important “task” or focus in the ongoing process of inclusive school development (Lütje-Klose & Urban, 2014).

We want to take a closer look at the school level based on a qualitative study on inclusive school development and quality criteria from teachers, school leaders and parents’ perspectives in the German context (Arndt & Werning, 2016, 2018): in retrospect, professionals described developing professional collaboration as one important milestone in their school development. With regard to collaboration between special and general education teachers on classroom level, a common starting point was a division of responsibilities in which special education teachers were responsible for students with special needs, while general teachers were responsible for the “regular students” by predominantly using the co-teaching approach; “one teach, one assist” or pull-out strategies. Developing collaboration was based on an emphasis on shared responsibility for all students and using a broader range of co-teaching approaches including switching roles (see for co-teaching approaches: → chapter on teamwork in the classroom). Developing professional collaboration appears interconnected with other areas of inclusive school development like ideas on student grouping and cooperation (see → chapter on cooperative learning).

On school level, three aspects appeared central for creating structures to support teamwork (Arndt, 2016):

| Composition of teams |

| Within their scope of influence, schools use different strategies in composing teams, for example, to create ‘manageable’ team sizes in large schools. Schools try to reduce complexity by focusing on teachers’ expertise in subject and/or areas in team composition. Another strategy focuses on creating continuity with regard to relationships between teachers and students. Combining both strategies, special and general education teachers form a classroom teacher team at one secondary school: One teacher goes along with the group from year 5 to 10, the other uses their expertise, for example, to facilitate transitions to upper secondary school or vocational training after year 10. |

| (External) Support for teamwork |

| Supporting teamwork and team development takes various forms: Linked to continuous professional development, schools focus e.g. on collaborative approaches to Individual Education Plans or developing their teaching approaches. Besides, they use external support like coaching or supervision/mentoring (see below Three Examples for Reflective). For instance, each new year 5 team receives coaching on team development in the beginning as well as a follow-up opportunity (like a “voucher”) for another coaching session. This takes into account that professionals with different backgrounds, frames of reference and professional languages might experience conflict while working together (Conderman, 2011). |

| Regular team meetings |

| As Kosorok Labhart and Maeder (2016) point out based on an ethnographic study in Swiss primary education, a lack of scheduled team meetings can burden one team member with organising a meeting. Adequate time to meet is considered as important for teachers’ professional development (Rytivaara & Kershner, 2012) as well as classroom practices and school development (Arndt & Werning, 2016). Hence, regularly scheduled team meetings are considered as important, while the lack of time for collaboration is considered a major constraint for working in multidisciplinary teams. |

Organising and Decision-making in Multidisciplinary Teams

On the school level, looking at creating structures to support multidisciplinary teamwork raises this question: Who organises multidisciplinary teamwork? Based on a mixed-methods longitudinal study in the German context, Lütje-Klose and colleagues (2016) emphasise the importance of school leaders’ support of multidisciplinary teamwork. Furthermore, questions concerning the role of teams in decision-making (Idel et al., 2012) arise. In the context of ongoing discussions on autonomy and collaboration (Fabel-Lamla et al., 2021; Kelchtermans, 2006), this leads to questions of autonomy on the team level as well as on participation in decision-making on institutional level.

Think about a school or educational institution:

Which decisions can teams make on their own?

Who participates in ‘fundamental decisions’ on an institutional level, for example, on working in age-mixed learning groups?

To make decisions and accomplish a common goal, team members should concentrate on collaborative, effective, and creative tasks and be able to merge their different thoughts and experiences (Volkova et al., 2021). The decision-making and support processes in an inclusive educational setting should involve all role-players equally. Thus, it is necessary to develop a cooperative partnership based on similar values, respect, open communication, common goals, and consideration of cultural differences (Nel et al., 2016). However, it is important to critically reflect on hierarchies and their influence on decision-making, for example, when professionals from medicine and education work together (Bauer, 2019).

Beyond the individual school, this is also linked to different approaches in educational leadership in the broader context: Is there an orientation towards distributed leadership like in the Finnish context (Heikka & Suhonen, 2019)? Or are school leaders more likely to act as the lonesome player though ideas of distributed leadership arise like in Austria (Pham-Xuan & Amman, 2020)? Hence, it is important to look “beyond the school gate” (Ainscow et al., 2012: 206). By way of example, we next focus on support structures on a regional level in Austria.

Support Structures on the Regional Level: The Austrian Departments of Inclusion, Diversity, and Special Education (FIDS)

In Austria, multidisciplinary teamwork in schools is highly influenced by the development of support structures on the regional level. The ratification of the UN CRPD in 2008 in Austria results in far-reaching changes for the Austrian education system. One of the central measures was the anchoring of inclusive model regions (Federal Ministry for Education and Woman, 2015) in three federal states of Austria (Tyrol, Steiermark, Kärnten). The plan was to gradually convert the special school system into an inclusive system through implementing a new support system and thus increase the integration rate at all Austrian schools (BMASGK, 2012: 65). From the beginning, these so-called Pedagogical Advisory Centres had the task to “provide, coordinate, advise and support inclusive education, especially special education, in their areas of responsibility to teachers who teach students with Special Education Needs or with disabilities in general schools. The form of support depends on the support needs of individual students and on the already developed inclusive quality of the class or school” (BMBF, 2015: 6). Multidisciplinary collaboration with key pedagogical and other actors has been a central concern of this reform from the beginning. The schools and the teachers should receive diverse support in the implementation of inclusive education and support in networking (with all relevant pre-school, post-school and out-of-school support systems).

Due to the education reform 2017/18 (Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung, 2017), the previous special education agendas of the Pedagogical Advisory Centres were transferred throughout Austria to the new federal-state authority “Education Directorate” and expanded to coordinate inclusive education. In each education directorate, a Pedagogical Service Department has been set up, which, in addition to quality management, cooperation in education controlling and pedagogical expertise in teaching staff management, is responsible for the overall management of inclusion, diversity issues and special needs education. Therefore, since 2018, diversity managers control the department and are professionally supported by pedagogical consultants (regional teachers). With the implementation of the concept at hand, the performance of the educational system with regard to its inclusion capacity is to be increased and the necessary support for each individual child with his or her individual support needs is to be ensured. In addition, experts from school psychology and regional personnel management are available for multidisciplinary co-operation in the educational region.

The new Department for Inclusion, Diversity and Special Education (FIDS) takes over the following tasks in the regions: Determination of (special educational) needs, provision of expertise in the field of inclusion, diversity and special education, participation in regional education monitoring, support of schools in all questions of inclusion/diversity/special education, support of transition processes, concept development of individual questions, parent counselling as well as networking with other school and non-school institutions (Lang, 2023). For these tasks, the FIDS have counselling teachers with different training who cover different areas: learning, behaviour, inclusion counselling, language education and language support. The guidance counsellors pursue the central goal of supporting all those involved in the school system in terms of inclusive teaching development (Lang, 2023). There are also other counselling teachers with a focus on physical and sensory disabilities (Lang, 2012).

School counselling addresses precisely the question of how lessons can be designed so that all children and young people can develop their individual talent potential and participate in both the educational process and the social processes at school? The individual needs of pupils are considered with regard to the existing conditions in the school and class, whereby systemic solution-oriented counselling is assumed here (Lang, 2023).

Key Aspect 4: Reflective Practices to Enhance Multidisciplinary Teamwork

As multidisciplinary teamwork is a complex endeavour, reflexivity is of great importance. Next, we focus on the relevance of reflective practices with regard to enhancing multidisciplinary teamwork. After this, we provide two examples for reflective practices.

Relevance of Reflective Practices

Teaching professionals operate within a framework characterised by constant changes and challenges. Teachers face a complex environment that encompasses cognitive, emotional, affective, and relational needs at both individual and group levels. Decision-making in teaching occurs in unique and unpredictable situations, blurring the line between theory and practice and influencing the overall teaching experience. These changes redefine didactic planning and the teacher’s role, shifting from someone who follows pre-established models to a professional who observes the learning environment and employs strategies to achieve predetermined objectives (Crotti, 2017).

Teaching practice is not simply a set of observable actions and reactions, but rather a complex network of relationships in which choices and decisions are made. The choices are influenced by conduct, languages, rules, objectives, and strategies that form the professional community’s “know-how” in teaching. In the face of classroom complexity, teachers often need to make rapid decisions. It is thus essential to accompany these decisions with meta-reflection, a form of “reflection-for-action”. This type of critical reflection extends beyond difficult or unexpected situations and also encompasses routine situations perceived as problematic. It involves understanding one’s experiences within the social context and utilising acquired knowledge for future practice. This is why reflection makes it possible to generate new skills and new expertise, since through a professional research and development programme teachers can gradually increase the ability to understand their work and as a result, improve it (Stenhouse, 1975).

As reflective professionals (Martins et al., 2015; Schon, 1983), teachers need spaces to reflect on their own professional identity and the contexts in which they are working. Schon (1983) identified two types of reflection in professional education: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. The first one allows teachers to reshape the activity on which they are working while it is unfolding, and it helps to reflect on unpredicted experiences so as to generate both a new understanding and a change in the situation. The second one concerns reflecting on an experience after it has occurred, in order to understand what happened and why they acted as they did.

Establishing communities of practice within the professional context allows reflection to operate collectively, bringing together experiences, history, culture, and shared language to find solutions to complex situations. Reflection in teamwork improves the exchange of knowledge and raises new understandings. Moreover, the multidisciplinary perspective enhances collaborative processes orientated towards seeking strategies with the awareness of working for (and with) all members of the community, students, parents, teachers and other professionals (Cadei, Deluigi & Pourtois, 2016). There are numerous reflection practices in teamwork: below three examples with a multidisciplinary perspective are described.

Two Examples for Reflective Practices in Multidisciplinary Teamwork

- Reflective Thinking in Multidisciplinary Teamwork

Reflective thinking plays a crucial role in multidisciplinary teamwork, particularly when sharing tacit knowledge across different professions. These aspects need to be explicit and shared among team members.

Knowledge of professionals include:

- personal knowledge

- values

- attitudes

- beliefs

- experiences

- theories

- philosophical-ethical elements

Reflective conversations among team members facilitate this process, allowing for the exploration and articulation of personal knowledge. Developing a multidisciplinary practical theory requires communication between implicit personal elements and conscious theoretical elements. Through this approach professionals with different backgrounds can detect differences between languages, concepts, working cultures, roles and identities.

The process of reflection, as Lakkala et al. stated (2017), has different stages and it begins with descriptive reflection, where team members identify a problem that needs to be addressed. Initially, the problem may seem ambiguous or undefined. Emotions and thoughts related to the problem are then examined, and it is framed within a conceptual framework.

Framing the experience enables team members to compare different aspects and questions related to the problem, referred to as comparative reflection. Multidisciplinary teamwork often involves tension and challenges, but it is important to acknowledge that conflicts between concrete experiences and analytic discussions are inherent to the learning process. By creating an atmosphere that allows dilemmas to surface, team members can reach a transformative point where they gain a broader understanding of the problem or reframe it through critically reflective analysis. The final phase of the reflective process is planning, where new solutions are sought and tested. This stage involves generating ideas and strategies to address the identified problem. Through this iterative process of reflection and action, multidisciplinary teams can enhance their collaboration and problem-solving abilities.

- Supervision

One important reflective practice to enhance multidisciplinary teamwork is supervision: The conjunctive key words in various definitions of supervision are learning, reflection and development (Ērgle & Rutka, 2016). According to Wiles (1967) supervision is the assistance of an external expert in the development of a better teaching learning situation. Moreover, as said by Goldhammer, Anderson and Krajeski (1980), supervision is supportive of teacher growth since it stimulates the professional development, influences teacher’s behaviour in the classroom and fosters the selection, development, use, and evaluation of good instructional approaches and materials.

Providing supervision at school can foster shared reflection on the changes observed in class, in which the highlighted dynamics became the subject of reflection from multiple views that were heterogeneous but at the same time, from a single community. The mediation of an external education professional also makes possible to channel shared views into strategies for new designs for the method, in line with the context of reference and its characteristics, in a virtuous circle of theory and practice that considers micro locations and specific skills, as well as opportunities and critical aspects. It is also a space in which to go further, where teachers use time away from bureaucratic issues to deal with educational stresses and the challenges connected to the class and the specific needs of individuals. Supervision spaces represent the chance to exchange knowledge and planning, to enable meta-reflection, to review actions in terms of their own reflected image and as a result, to recognise and appreciate the images of students with their differences and identities (Cuccu, 2022).

Supervision can be divided into steps as follow:

Figure 3: Phases of Supervision

Key Aspect 5: Multidisciplinary Teamwork in Pre-service and In-service Teacher Education

For academia to acknowledge that it dominates the design and the process of implementation of teacher education today (Zeichner, 2018, 2022) is a crucial step forward to understanding what funds of knowledge are usually left out and how they could fill the gaps that appear later in teachers’ careers. This is neither an easy fix nor a fast one, which makes it complex and even messy at times. A multi-year and multi-layered approach to working along existing teams and learning to build new multidisciplinary teams is realistic and is precisely what we should aim for in the future of teacher education and for a more collaborative future of education research. (The Collaborative Education Research Collective, 2023)

Students acquire competencies to develop and implement inclusive practices in multidisciplinary teams. The training of future teachers is confronted with the challenge of implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, (United Nations, 2006), also in the field of education. Student teachers also see themselves obliged to meet these requirements and in doing so encounter a school system that is in the middle of a transition process. The associated paradigm shift within teacher training is therefore of great importance, because an inclusive school system requires educators who are able to co-operate in a team and who do not (any longer) take on the role of lonesome player.

Against the background of these developments in society as a whole, the professional profile of teachers is also changing in the sense that networked and cooperative work by all “education professionals” (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022: 18) is of central importance in order to meet the demands of inclusive education: “Teachers do not work in isolation, nor do they work in homogeneous groups of teachers. Inclusive practice is performed by teams of diverse professionals. Therefore, a broader perspective is needed to prepare and support school staff and school professional networks to implement and sustain inclusive practice” (ibid., :18). (See → chapter on “Teamwork in the classroom”)

Designing Initial Teacher Education at University of Innsbruck (Austria)

The teaching model of the University of Innsbruck (Austria) attempts to form a new teacher personality for the current challenges. The focus is on establishing a professional ethos that considers cooperation with different actors in the school system as enriching and profitable in order to be able to professionally meet the diverse needs of the students (Sonntag, 2023). The teaching concept implies close cooperation with different actors in the educational landscape at Tyrol/Austria (Department of Inclusion, Diversity and Special Education of the Tyrol Directorate of Education, inclusion educators, and guidance counsellors) in order to prepare prospective students for this. In addition, the concept offers a wealth of opportunities for personal discussion, which in the context of a seminar-accompanying learning diary stimulates the basis for the students’ self-reflective learning. The seminar is characterised by a variety of methods: in addition to more classical teaching-learning methods (impulse lectures, literature studies, seminar discussions and group work), there are also teaching methods that contribute in particular to students’ personal development (work with the so-called learning diary). Teaching methods that enable a concrete interlocking of scientific theories with professional practice (work phases with external experts or actors from the educational landscape) as well as teaching methods that are research-oriented (qualitative interviews in the form of group discussions at the end of the course, qualitative evaluation of the learning diaries) and represent an important link between teaching and research.

The aim of the learning diaries is to encourage students to engage in “deep learning” (Bräuer, 2016: 22) through a continuous reflection process. On the one hand, regular written follow-up and reflection should enable deeper insights into the seminar content covered. On the other hand, this procedure also creates opportunities to elaborate and reflect on the individual learning process. In this respect, these “knowledge stocks […] form a basis for the formation of schemata and scripts relevant to professional practice” ( te Poel, Schlag, Lischka-Schmidt, Wittek, Hartung-Beck & Bauer 2022: 125). The focus is primarily on aspects that are subjectively particularly significant for the students.

Prospective teachers need (specialist) knowledge about different professional groups, structures, theories, models, and concepts of cooperation in schools, about local supporting guidance structures and actors or institutions. They need communication skills to build trusting networks and effective cooperation. Empathy and willingness to adopt perspectives are a prerequisite.

Case-based Approaches in Pre-service and In-service Teacher Education: Reflecting on (Re-)Producing Differences in Multidisciplinary Teams

Within the project “Reflection, Achievement & Inclusion.“ a qualitative study was conducted at two comprehensive schools and two advanced secondary schools (‘Gymnasien’). Based on this, materials for case-based approaches for both pre-service were developed (Arndt et al., 2021) and in-service teacher education (Lau & Lübeck, 2021). In one workshop of continuous professional development general and special education teachers of one school participated, including the one who is leading the educational stage group and the one who is responsible for the school’s concept on inclusive education. During the workshop professionals discussed general and special education teachers’ collaboration in student assessment which led to critically reflecting on their current teaching concepts and practices. For instance, they had introduced using a specific room as a flexible way for individual students to work outside the classroom based on their situation-specific needs. However, during the workshop professionals critically reflect on their observation that this room was now used for the pull-out of students with special needs: Students with special needs were pulled out of the classroom during the lessons to provide instruction for them. Professionals started to share first ideas on how to change this structure and practices to provide more flexible support for all students (Lau et al., 2021).

The use of pull-out strategies varies across context and also within schools (Arndt & Werning, 2016; Scruggs et al, 2007). As there is a risk of stigmatisation for students who are pulled out often, pull-out is a good example to demonstrate why it is important to reflect on the (unintended) consequences of division of task and responsibility within a multidisciplinary team. One possible starting point is to take a closer look at students’ perspectives within cased-based approaches in teacher education.

Example for Casuistic Material: Student’s Perspective

At one comprehensive school, in 6th grade, the student Tim was interviewed. The interviews were conducted in German. We refer to a translated and slightly shortened version (see for the original excerpt from the interview: Arndt et al., 2021:11). The interviewer who also conducted participant observation refers to students who sometimes work in a small group and ask Tim about it. Tim states:

“In the small group, it’s something quite different from the large group. You understand much faster and better in the small group, because […] it’s the four of us and Mrs. Peters [special education teacher] explains everything individually. If you need help, it takes only one or two minutes or like thirty seconds.”

Tim explains that they are taught separately (‘to be outside’) in the main subjects like Maths, German lessons and English. They work on teaching and learning material which is easier compared to the one of the students within the (main) classroom. Tim prefers to work in the “large” (main) classroom or group. The interviewer asks if Tim can explain why. Tim tells:

“Because it’s much better in the large [main] classroom. […] The teacher also explains really well. I rather prefer to stay inside. […] If we are in the small group […], well I don’t know, but I want to be in the large/main group. […] Because the ones in the large group will have more success. They will get a Realschulabschluss […] or […] Gymnasialabschluss.

Asked about the small group, Tim adds: “And in the small group, we can only get a Hauptschulabschluss”. Tim refers to different school leaving certificates in the German stratified school system: “Hauptschulabschluss” refers to the general education leaving certificate after 9th grade (lower secondary school). “Realschulabschluss” refers to the general school leaving certificate after 10thgrade, “Gymnasialabschluss” refers to the Abitur which is the secondary school leaving certificate after 12/13 years and general higher education entrance qualification.

What is your first impression when you read about this?

How does Tim characterise the “small” and the “large/main” group?

Based on interviews with students on primary level, Laubner (2014) refers to special education teachers as ‘highlighting the difference’ (by pulling-out students with special needs). Take this as a starting point for discussing potential unintended consequences of roles and responsibilities in multidisciplinary teams.

Engaging with students’ views (Messiou, 2019) can form a starting point to reflect on unintended consequences and (re)producing of difference in multidisciplinary teamwork. As classrooms are not only sites of responding to differences, but also of (re)producing differences with regard to intersecting “difference categories” (Plösser & Mecheril, 2012: 797), reflecting on constructions of differences in pre-service and in-service teacher education is important with respect to multidisciplinary teamwork. Multidisciplinary teamwork can also be characterised by underlining tensions if (specialist) support is linked to certain “target groups”, especially in funding (Moser, 2017). Based on a qualitative study on multidisciplinary collaboration in Denmark, Hansen et al. (2020) raise questions on direct forms of provision in which the specialist works directly with the child as well as indirect forms in which the specialist works directly with the teacher and indirectly supports the child.

A Closer Look at Example Case I: Finnish Early Childhood Education – Multidisciplinary by Design

The Finnish ECEC is multidisciplinary by design: it was initially under the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health until 2013, which has influenced how the daily teamwork and leadership of early childhood is still organised today (Kinos, 2008). Known as Educare or ECEC (Early childhood education and care), it strongly relies on multidisciplinary teamwork ideology and comprises care, education, and teaching, seen as an open care or community care system. Groups of multi-skilled professionals are involved in a child-centred task together (Solvason & Winwood, 2022): early childhood healthcare services, primary healthcare, specialised medical care, developmental disability services, and social services, are all highly involved in a wide range of activities in the child’s life to support the flow of ECEC and other aspects of life (Äikäs & Pesonen, 2022).

Early interventions can influence the entire life of a child. Early years are recognised as being critical times when children’s development depends on various factors and when with the intentional help of daycare professionals, children’s and families’ safety and well-being can be considerably increased and supported accordingly. A multidisciplinary team, with a larger array of qualifications and perspectives, is more prone to provide profiled support, for example, for families with special needs, as well as guide them to attend child guidance clinics or other special services (Pölkki & Vornanen, 2016). Therefore, what better time than early years for multidisciplinary teams to work collaboratively to influence the beginning of the story, so that they can influence the whole story? (Belloni, 2019).

Pedagogical and Welfare Professionals and their Qualifications

The regular contact staff in ECEC consists of Pedagogical professionals and Welfare professionals (Onnismaa, 2017):

- Kindergarten Teacher (Lastentarhanopettaja)

- Social Welfare Worker (Sosionomi)

- Practical Nurse/ Nursery Nurse (Lähihoitaja)

- Children’s Instructor/Childcare Worker (Lastenohjaaja)

- Special Education Teacher (Erityislastentarhanopettaja or Varhaiskasvatuksen erityisopettaja)

- Special Needs Assistant (Avustaja)

Other professionals that might supplement the needs of the regular contact staff can be kindergarten teachers who become specialised in one particular, for example:

- Finnish as a second language teachers (can be dedicated to one daycare or can travel in between daycares to support children with cultural and linguistic diverse backgrounds)

- Curriculum developers (who are dedicated to one daycare and help improve their curriculum)

- Psychologists

- Therapists (e.g., Speech, Art)

The minimum qualification requirements for ECEC staff in Finland varies a lot. Approximately 30% of all employees have tertiary-level education. The highest level of training is required to become:

- a Kindergarten Teacher – Bachelor’s degree of 3 years of university training specialising in early childhood education

- a Social Welfare Worker – Bachelor’s degree of 3½ years higher education institution (polytechnic) specialising in social services

- a Special Education Teacher (early childhood) – 1-year postgraduate university study route in special needs education following qualification as Kindergarten Teacher (university route) and 2 years work experience as Kindergarten Teacher

All three are core practitioners with group responsibilities and can also be centre heads (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2017).

It is important to mention that as part of their studies in education, future kindergarten teachers study Pedagogical leadership and multidisciplinary cooperation (University of Helsinki, 2023), and then during their workplace learning they become acquainted with administration and working as a member of multidisciplinary teams and networks. So, becoming an active member of a multidisciplinary team is highly regarded in Finland and is given space and time to be studied and practised even before being a qualified EC teacher.

Approximatively 70% of the Finnish ECEC staff has vocational training, which is required for:

- Practical Nurse/ Nursery Nurse (3 years upper secondary vocational qualification in social welfare and health care)

- Children’s Instructor/Childcare Worker (3 years upper secondary vocational qualification in childcare, education, and family welfare)

- Special Needs Assistant (Recommended: 1–2 years vocational training)

The first two are qualified co-workers and the last one is a non-qualified co-worker.

Roles and Responsibilities

Some of the Kindergarten teachers’ responsibilities are: teaching the group; creating individual study plans and following their implementation in co-operation with the educational team; evaluating and developing the culture of the whole educational community; multidisciplinary and networked cooperation between the school, the health service and the with the health care and special services for children, especially when this cooperation is related to the child’s development and learning issues; cooperating with families; developing practices that enable parents to participate in the development of early childhood education and care activities; communicating the pedagogical activities of the group.