Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

Neuroinclusion: A School Community Approach

Alison Stapleton; Deirdre Forde; Nicola Ryan; and Paty Paliokosta

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Imagine a neurodivergent child arriving at school on a Monday morning. For them, the transition to the classroom after a hectic weekend feels difficult. In the chaos of the morning rush, they have forgotten to bring their lunch, and one of their socks is on inside out. On mornings that run more smoothly, this child comes to school well-rested and ready to work. Today, however, they feel tired.

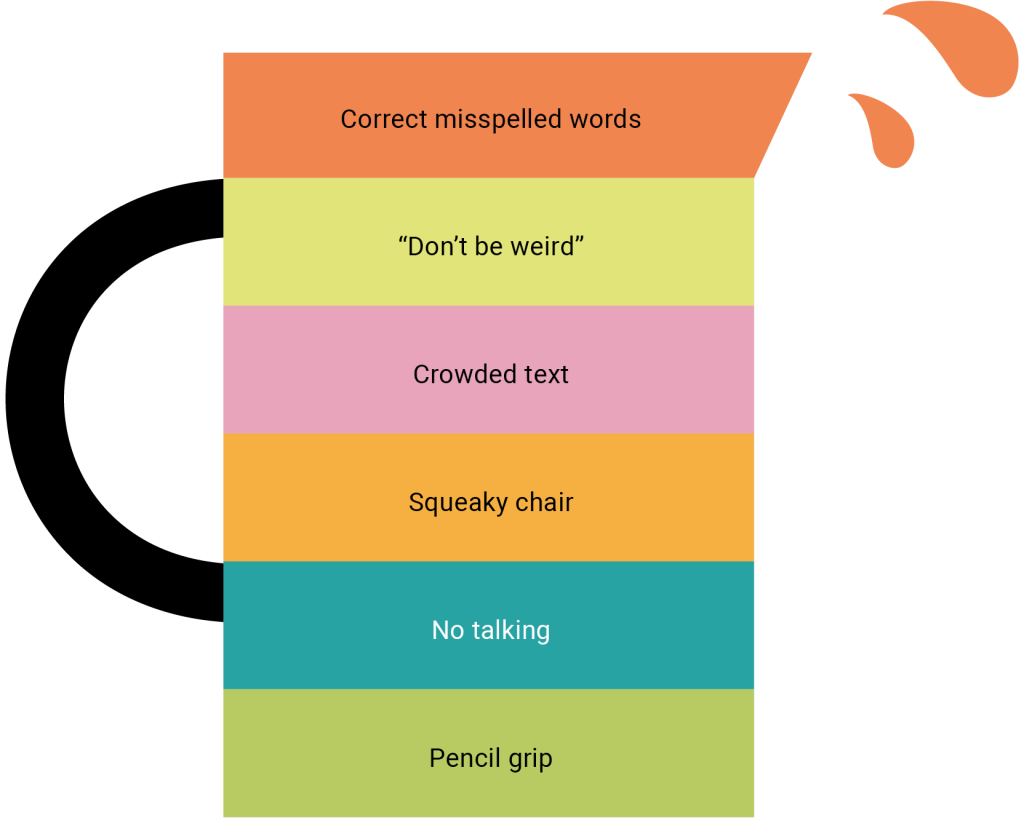

As teacher hands out a worksheet, they describe what they would like the class to do. The child does their best to listen and remember each demand because they want to do well in school even when they are tired. Teacher explains that they want to see each child holding their pencil correctly, not talking to the person seated beside them, and sitting quietly in their chair. The neurodivergent child begins to worry; holding the pencil “correctly” means that their hand gets tired very quickly, and sometimes they find it easier to read when they whisper to themselves. In addition, the neurodivergent child is seated in a squeaky chair, which means they cannot tap their foot and sit quietly at the same time. On top of this, the neurodivergent child notices that teacher’s handout has crowded text, which is more difficult for them to read. As their sense of worry grows, the neurodivergent child becomes increasingly aware of the other people around them. They do not want to seem “weird”, so they try to calm down and focus. Teacher then says, “Okay, class. Let’s begin with a simple task. Correct the misspelled words on the handout”.

One way to understand this child’s experience is by using the metaphor of a capacity jug. This morning, the child had a smaller capacity jug than they normally would, meaning that their capacity jug became full quite quickly. And, with all of the demands, the teacher’s “simple” task could not fit neatly in their capacity jug; the “simple” task causes it to overflow. Yet, the child’s day does not end there. We can imagine how the rest of their day might go as they struggle to tolerate keeping their collared shirt buttoned up, as their friend chats with them about their favourite TV show, as the various school bells sound for lunch times, as they go to the sweet shop on their walk home from school. We can imagine their capacity jug growing and shrinking, becoming more or less full depending on the situation and task at hand. We might also notice times when a task did not need to entail so many demands and could have filled the capacity jug less.

There are many variants of this metaphor, however, this version is adapted from Holly Sutherland (2023). The point is that each of us has a capacity jug, with different demands filling our jugs in different ways. This chapter focuses on neuroinclusion and how communities might create a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem that helps us all to gently expand our capacity jugs, to notice what fills them, and to notice times when demands can be reduced to prevent our capacity jugs from overflowing.

Figure 1: An overflowing capacity jug does not have space for a supposed “simple” task.

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is neurodiversity?

- Why are neurodiversity movements necessary for neuroinclusion?

- How might we create a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem?

Introduction to Topic

The diversity within neurodiversity: A preface

Building on Steven Kapp’s (2020) discussion of the diversity within neurodiversity, we would like to acknowledge that there are many ways to approach the concepts covered in this chapter. We would also like to acknowledge that because many people care deeply about this topic, and because this topic can require using new terminology, it can feel risky to engage. Importantly, the meaning of many concepts outlined in this chapter is evolving (Patrick Dwyer, 2022). In addition, conceptualisation and language preferences differ across contexts, as do individual preferences. Therefore, we would like to emphasise that we are not saying ours is the “correct” way to approach this topic. Rather, aligning with Robert Chapman (2020, p.219), the present approach is one we have found to be “epistemically useful” and invaluable in our practices. We are sharing our views at this point in time in the hopes that they help to resource and nurture neuroinclusive communities.

What is neurodiversity?

Collectively developed through the 1990s and 2000s (Monique Botha et al., 2024), in a descriptive sense, “neurodiversity” refers to the fact that all human nervous systems work differently (Steven Kapp, 2020). This means that each of us experiences the world in different ways, and thus we act in different ways. From this perspective, neurodiversity is a subset of biodiversity and a biological fact (Steven Kapp, 2020). The existence of terms like autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and more may be attributed to this fact. If each of our nervous systems worked in the exact same way, then we would not have terms to describe differences from supposed norms (neurodivergences); these terms are a consequence of the fact of neurodiversity. As a concept, neurodiversity includes all types of nervous systems (neurotypes).

Being neurodivergent means having a nervous system that works differently from what is considered “normal”. Importantly, there is no consensus on who is considered neurodivergent (Steven Kapp, 2020). For example, sometimes the term “neurodivergent” is used to exclusively refer to people with neurodevelopmental differences (e.g., autism) and not people who have an acquired brain injury or trauma. This chapter does not impose limits on the meaning of “neurodivergent” and instead, aligning with Steven Kapp (2020), invites readers to identify and organise within neurodiversity movements at their own discretion.

If you are not neurodivergent, then you are neurotypical (i.e., neurotypical people have nervous systems that work in “normal” ways). The only way to identify someone as neurotypical is by ruling out all forms of neurodivergence. Therefore, it is best practice to not assume that someone is neurotypical. Some scholars and advocates suggest that neuronormalised may be a more appropriate term than neurotypical and that neurominoritised may be a more appropriate term than neurodivergent. Amandine Catala (2023) argues that these alternative terms decenter socially accepted (neuronormative) points of reference and serve to highlight the social positions created by the associated power relations. In simpler terms, although neurodiversity is naturally occurring, the way we “judge” neurotypes is not. Instead, what we consider “normal” depends on our context (i.e., which neurotype has more power). So, from this perspective, being “neurodivergent” means having less power in that context. Approaching these concepts in this way can be pragmatically useful because it allows us to distinguish between people who are likely harmed by existing systems versus not. However, given the risk of conflating “being neurodivergent” with “experiencing disability”, and given that the terms “neurodivergent” and “neurotypical” are more commonly used, neurodivergent and neurotypical are used throughout this chapter.

What is a neurodiversity paradigm?

A neurodiversity paradigm is an application of neurodiversity at a conceptual level. Nick Walker’s (2021) neurodiversity paradigm contains three fundamental principles:

- Neurodiversity is a naturally occurring, valuable form of human diversity. This means that (i) neurodiversity is not something we create artificially, and (ii) strength is a collective property of diversity; the fact that we are all different is a strength.

- “Normality” is a social construct. Just as there is no “correct” ethnicity or gender, there is no universally “correct” nervous system. No one “way of being” (neurotype) is inherently better than any other.

- Neurodiversity operates like other dimensions of equality and diversity, such as ethnicity or gender. This means that neurodiversity is subject to the same types of social dynamics (e.g., privilege and oppression). For this reason, it can be helpful to approach and affirm neurodiversity similarly to the ways we approach other dimensions of human diversity.

To illustrate the principles of Nick Walker’s (2021) neurodiversity paradigm, consider the following metaphor (adapted by Alison Stapleton from Alyssa Alcorn et al.’s (2022) woodland metaphor):

Imagine a rainy garden that has lots of plants, specifically one lantern plant, two rose bushes, three viola tricolors, and lots of iris plants. Too many iris plants to count! In fact, most of the plants in this garden are iris plants. In this garden, we can see all three tenets of Nick Walker’s (2021) neurodiversity paradigm operating.

First, the variation between plants is an inherent property of the biodiversity in the garden; by nature, each plant is unique. For example, no two iris plants lean in exactly the same way or have the exact same patterns on their leaves. And yet, even though all plants differ, it is helpful to use the term “iris” to refer to the class of iris plants. We can also see the strength that comes from diversity; the garden is a rich and varied oasis rather than being home to just one type of plant.

Second, all plants in this garden have equal value. We would not say that the lantern plant is inferior to the iris plant, nor would we berate the lantern plant because it did not grow long green leaves like an iris plant. The lantern plant has equal value as a plant. Whether a plant is thriving depends on its environment. For example, lantern plants are prone to root rot if overwatered. This means that it is difficult for the lantern plant to thrive in the rainy garden. Similarly, the garden has snails that eat rose bush leaves, so the roses cannot thrive. This particular garden is also home to a dog that enjoys eating viola tricolors, so those plants cannot thrive.

Finally, we can see that iris plants are in the majority. By default, environments tend not to serve minority groups. Unlike the minority plants, iris plants thrive with lots of rain and are rarely targeted by snails or the dog. Hence, iris plants thrive in the garden because they do not experience the same stressors as the minority plants; the same garden environment is experienced in different ways. So, rather than blaming a plant for not thriving, we can instead shift our focus to plant-environment fit. How can we change our garden so that all plants have maximum opportunities to thrive?

In the same way that each plant is unique in the garden metaphor, each person is unique; even people who share the same neurotype are not the exact same. Yet, it can be helpful to provide people with labels to describe shared ways of experiencing the world (Juwayriyah Nayyar et al., 2024); terms for describing neurotypes can be useful. Similarly, just as the minority plants experienced stressors, neurominorities experience minority stressors such as everyday discrimination and internalised ableism (Monique Botha & David Frost, 2018). In line with minority stress theory, these stressors, including the demands of neuronormative standards (e.g., “you must make eye contact when listening to me”), increase neurominorities’ risk of poorer health outcomes (Monique Botha & David Frost, 2018). Importantly, in this context, “minority” and “majority” do not merely reflect differences in numeric quantity. Instead, these terms are intended to highlight differences in power.

In terms of applications, rather than blaming a neurodivergent child for struggling/not thriving, the outlined neurodiversity paradigm allows us to add the environment to our analysis. Attending to person-environment fit offers teachers alternative pathways for supporting neurodivergent children; what can we change in our classrooms so that all children have maximum opportunities to thrive? In this way, teachers can embrace neurodiversity paradigms (be neurodiversity-affirming) and advance neurodiversity movements (be neuroinclusive).

What are some myths and misconceptions about neurodiversity?

If we adopt neurodiversity rhetoric without an understanding of the associated movements and paradigms, then we risk failing to achieve its transformative potential, impeding meaningful change, and/or causing active harm (Dinah Aitken & Sue Fletcher-Watson, 2022). Common myths and misconceptions about neurodiversity and its associated paradigms include:

Myth 1: “When we talk about neurodiversity, we are not talking about the entire human population, rather we are talking about a subset of neurodivergent people”.

This is a myth because neurodiversity includes everyone, and, as outlined, neurodiversity is not a synonym for “being neurodivergent”. If we apply neurodiversity to just a subset of the human population, then we risk merely replacing dominant terms with neurodiversity rhetoric rather than enacting meaningful system-level change. We also risk reinforcing stigma, further ossifying “us-them” (neurotypical-neurodivergent) categories, and centering neurotypical experiences. In order to push back against stigma, we need a language that includes everyone; neurotypical people are not outside of neurodiversity.

Myth 2: “Neurodiversity is only about celebrating neurodivergent talent”.

Although it is important to identify, celebrate, and nurture an individual person’s strengths, focusing on individual talents alone does not fully realise the potential of neurodiversity. Relatedly, “superpower” narratives that stereotype neurodivergent people as having special talents may also result in exploitation and reflect performative activism (Patrick Dwyer et al., 2024).

Rather than just centering neurodivergent talent, neurodiversity paradigms can allow us to understand the differences between people as a source of strength. For example, Harriet Axbey et al. (2023) found that, in comparison to neurotype-matching pairs, neurotype-mismatching pairs (e.g., one autistic person and one non-autistic person) worked more creatively when completing a task together.

Relatedly, if we are truly valuing people equally, whether they have a talent is irrelevant; we all have equal value regardless of our strengths and support needs. A failure to frame strength as a collective property risks pressuring neurodivergent people to outperform their peers or somehow compensate for being neurodivergent. It also risks reinforcing systems that value people only by their grades or productivity (Dinah Aitken & Sue Fletcher-Watson, 2022). Critically, who decides what “talents” are? What happens to children who believe that they do not have any talents? How different might our communities be if everyone believed that they had value simply because they were a member of the community?

Myth 3: “Neurodiversity erases the struggles of neurodivergent people”.

When we argue that a neurotype is not solely characterised by deficits, that does not mean that we ignore experiences of disability. Embracing neurodiversity movements can involve identifying ways to improve person-environment fit rather than solely framing problems as being located within individual people. In this way, it is possible to reject deficit-focused labels while also attending to experiences of disability. As a movement, neurodiversity can be both needs-affirming and rights-respecting. As Dinah Aitken and Sue Fletcher-Watson (2022) note, “the word difference should point us to acceptance of needs without judgement, rather than denial of needs without support”.

Importantly, there are debates about the extent to which neurodiversity movements represent the needs and interests of neurodivergent people who have relatively higher support needs (Jonathan Green, 2023). However, the movement is intended to include everyone; it is important to continually decenter dominant perspectives and ensure all neurotypes are represented.

Related to assertions that embracing neurodiversity erases struggle, sometimes neurodiversity-affirming practice is framed as necessitating a total rejection of conceptualisations of neurodivergences as “disorders” and “deficits” rooted in biology (medical models of disability). Aligning with this, Patrick Dwyer et al. (2024) found that, in a sample of 504 adults with a connection to autism (278 autistic, 226 non-autistic), neurodiversity movement support/identification predicted lesser endorsement of medical models. Yet, Julia Knopes (2024) reported that neurodivergent people’s understanding of their lived experience indicated ambivalence towards medical and neurodiversity models, concluding that “rather than imposing one model of disability over another, we might instead pause to consider how people apply different models to appreciate different aspects of their day-to-day lives” (p.27). For teachers, this might mean respecting an individual child’s way of understanding themselves and not limiting the child’s narrative to one of strength and difference.

At times, depending on the jurisdiction, teachers may be asked to contribute to identification processes for neurodivergent children. In contexts where neurodivergent children are identified solely per pathologising models and where formal identification is required for access to accommodations and support, it is particularly important for teachers to name children’s struggles. By reporting on struggles honestly and gently, with respect and compassion, teachers can help neurodivergent children and their families to access effective support as needed and wanted.

Myth 4: “Being neurodiversity-affirming means anything goes”.

In the context of rights-respecting movements, neurodiversity does not mean that “anything goes” (i.e., that there are no boundaries or rules). Being neuroinclusive means facilitating the cohabitation of all neurotypes, not prioritising one form of needs/preferences over others. Everyone must be aware of the multiple intersections that they occupy and reflect on whether they are using their power in ways that harm others who have less power. Being neuroinclusive means asking questions like, what can I change in this environment to make it safer and more comfortable for everyone?

The present chapter

This chapter employs a participatory approach and reflects a collaboration between neurodivergent and neurotypical professionals and advocates. In this chapter, we explore why neurodiversity movements are necessary for neuroinclusion and how communities might create a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem. We adopt a needs-affirming, rights-respecting approach and aim to cultivate neuroinclusive communities that affirm and accommodate all neurotypes.

Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory to Conceptualise the Community

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979; 1986) ecological systems theory (EST; later termed the “bioecological model”) suggests that children’s growth and development are influenced by a set of interconnected environmental systems, namely the microsystem (e.g., teacher-child interactions), mesosystem (e.g., teacher-parent interactions), exosystem (e.g., disability organisations), macrosystem (e.g., neuronormativity), and chronosystem (e.g., neurodiversity movements). Bronfenbrenner depicted these systems as concentric circles, with each system arising from “a place where people can readily engage in face-to-face interaction” (Urie Bronfenbrenner 1979, p.22). EST emphasises the importance of studying a child in the context of multiple ecological systems in order to fully understand their development. As such, the EST framework presents the child at the centre surrounded by influencing subsystems of the environment, the most influential and intimate of which is closest to the child. EST helps us to understand that children and their families do not exist in isolation but rather are embedded into a larger social structure interconnected with other institutions and domains which can indirectly impact the immediate environment of the child. And, from this perspective, development arises as a result of reciprocal processes between a developing child and their systems. For this reason, we argue that a neurodiversity-affirming systems approach is necessary to cultivate neuroinclusion.

Why are Neurodiversity Movements Necessary for Neuroinclusion?

Neurodiversity movements can help us to decenter medical models of disability.

We can reframe supposed “deficits” as differences or strengths.

Historically, medical models of disability have been viewed as oppressive (Andrew Hogan, 2019). At an ideological level, medical models have been described as “personal tragedy models” because they tend to frame disability as “something to be pitied, a personal tragedy for both the individual and [their] family” (Licia Carlson, 2010, p.5). As conceptualisation frameworks, medical models approach forms of neurodivergence as “disorders” and “deficits” rooted in biology that should be cured, prevented, or suppressed. From this perspective, forms of neurodivergence are viewed as “pathological” deviations from “normal” human species functioning that directly lead to the experience of disability. Hence, medical models can be understood as placing the “problem” solely within neurodivergent people.

Many people believe that the goals and attitudes of neurodiversity movements and medical models are dissimilar (Patrick Dwyer et al., 2024). And, depending on how one defines “neurodiversity”, this may be true (Ari Ne’eman and Elizabeth Pellicano, 2022). Yet, mandating a total rejection of medical models may reflect an epistemic injustice (Julia Knopes, 2024), and some neurodiversity approaches aimed to offer a middle ground between medical and other models of disability (Patrick Dwyer, 2022). Hence, rather than imposing a singular model of disability through which neurodivergent people must understand their own experiences, being neurodiversity-affirming may require creating space for multiple types of stories, including those stemming from medical models (Robert Chapman, 2021).

Across contexts, many professionals rely on medical models of disability. For example, many neurodivergent people are identified per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th Edition (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2022). Neurodiversity movements provide an opportunity to decenter dominant approaches to neurodivergence, including those grounded in medical models. Extending beyond traditional medical models, adopting a neurodiversity-affirming stance allows us to attend to person-environment fit. Rather than asserting that a neurodivergent person just needs to be “fixed”, we can expand our lens to include the environment, since the “problem” may be that it is unaccommodating and unaccepting. In addition, rather than pathologising all differences, we can broaden our awareness of the contexts that transform differences into disabilities, and indeed the contexts that support differences serving as strengths.

We can cultivate neurodivergent identities.

Strong medical models tend to only use language that perpetuates stigma, upholds neuronormative standards, and reinforces unfavourable evaluations of neurodivergent people, contributing to ongoing discrimination and marginalisation (Patrick Dwyer, 2022). In contrast, neurodiversity theorist Robert Chapman (2021) calls for a “rejection of default pathologisation of neurodivergence, not of neurodivergent pathologisation as such”. In line with this, neurodiversity movements tend to use language that affirms neurodiversity, facilitates greater acceptance of neurodivergent people, and validates neurodivergent identities. By using language that highlights how every human nervous system is unique, neurodiversity movements center collective strength, thus creating opportunities for all members of the community to maintain a sense of belonging and value. This shift in terminology and understanding is crucial to dismantle neuronormative systems, redress harm caused, and nurture neuroinclusive communities where neurodivergent people are valued and understood.

In addition, some neurodivergent people describe forging their neurodivergent identity as crucial to self-understanding, with neurotype serving as a useful framework for working with their nervous system (Juwayriyah Nayyar et al., 2024). Hence, rather than only using deficit approaches (replacing neurodivergent culture with neuronormalised practices) or difference approaches (teaching neuronormalised practices without regard for neurodivergent culture), true neuroinclusion necessitates an asset-based approach. In this context, an asset-based approach might look like explaining neuronormative standards while actively sustaining neurodivergent culture; inviting all community members to notice their differences, how no one way of being is superior, and how it is not enough to merely respect neurodivergent culture – we must also extend it. See Django Paris (2012) for a discussion of this type of culturally sustaining pedagogy; remember neurodiversity is understood as operating like other dimensions of equality and diversity.

We can empower neurominorities and protect neurominorities’ autonomy.

By framing scientists and doctors as cognitive authorities, medical models tend to perpetuate power imbalances and a sense of “us-them”, furthering the divide between neuromajorities and neurominorities. This differential treatment can mean that neurodivergent people are viewed as incapable of autonomy, which can lead to a loss of agency and the ability to make decisions about their own lives. This can exacerbate societal exclusion and subjugation.

In contrast, neurodiversity-affirming approaches aim to empower neurominorities and return power to neurodivergent people, protecting their autonomy and agency. This approach is not only more inclusive and supportive but also upholds the rights-based perspective of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006).

Neurodiversity movements can help us to improve our understanding of neurodivergent people’s experiences.

Neurodivergent people tend to be misunderstood, in part due to neuronormativity. For example, the way a neurodivergent person expresses their emotions may radically differ from the way a neurotypical person expresses their emotions. In line with Nick Walker’s (2021) neurodiversity paradigm, no one way of expressing yourself is “correct”, and thus both “ways of being” are of equal value. However, neuronormativity devalues authentic neurodivergent expression in favour of neurotypicality. This means that neurodivergent people can be judged in less favourable ways than their neurotypical peers, with Noah Sasson and colleagues (2017) reporting that lesser favourable judgements of neurodivergent people were associated with lesser willingness to interact.

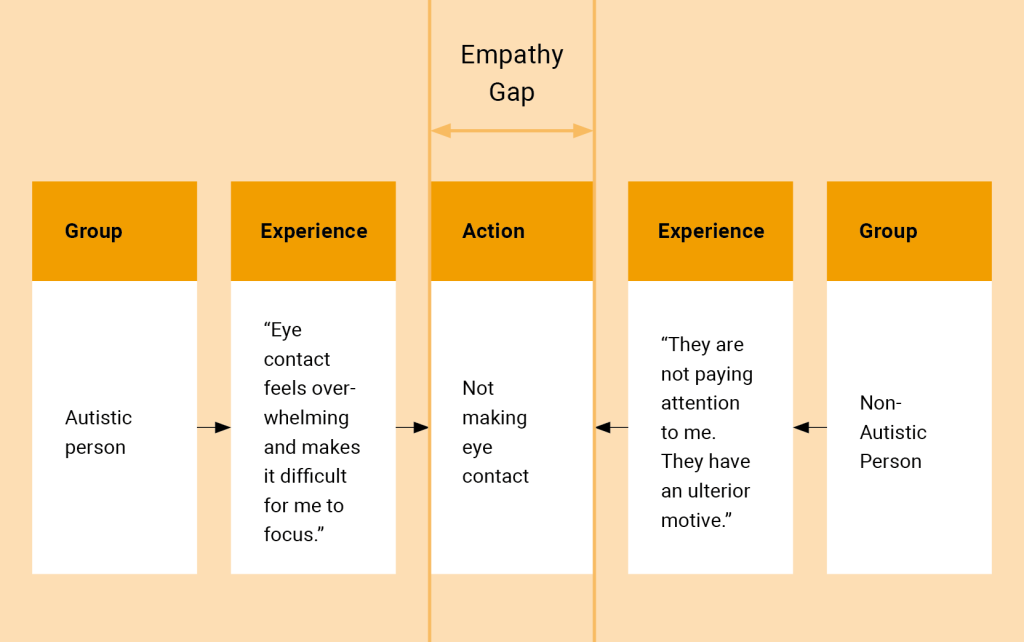

One conceptualisation of misunderstandings of neurominorities that is consistent with Nick Walker’s (2021) neurodiversity paradigm comes from Damien Milton’s (2012) theory of the double empathy problem. According to this theory, members of different social groups have different experiences and viewpoints on the world (i.e., have an empathy gap). For this reason, miscommunications are likely to occur when members of different groups interact. From this perspective, the “problem” with communication is experienced by both group members (i.e., it is a double problem). And yet, there is inequality to its impact. Power dynamics mean that minority group members are often expected to fully and completely cross the empathy gap (i.e., adjust their responding to better meet the needs and preferences of majority group members). In addition, because majority group members tend not to experience miscommunications, they experience the resulting sense of disconnection as more intense, while miscommunications are understood to be a common experience for minority group members.

To illustrate the double empathy problem, consider the following example. While interacting with a non-autistic person, an autistic person does not make eye contact. From the perspective of the autistic person, they are not making eye contact because it feels overwhelming and makes it more difficult for them to fully attend to what their conversational partner is saying. And yet, the non-autistic person interprets this action as meaning that the autistic person is not paying attention and has an ulterior motive.

In this example, we have two members of two different groups, and thus, we have an empathy gap. A neuronormative way to resolve this empathy gap might involve mandating that the autistic person make eye contact, regardless of how it impacts their ability to engage with their conversational partner. Alternatively, a more neurodiversity-affirming way to approach the empathy gap might involve acknowledging that both the autistic and non-autistic experiences are valid and valuable. Therefore, it is possible for both the autistic and the non-autistic person to adjust their responding. In fact, research has shown that autistic-to-autistic communication is just as effective as non-autistic-to-non-autistic communication (Catherine Crompton et al., 2020). So, it is not valid to assert that a neuronormalised approach to communication is “better”. Importantly, neurodiversity paradigms do not dictate how we should approach the empathy gap. Instead, neurodiversity movements invite us to affirm both “ways of being” and think critically about who is crossing the empathy gap and why.

Figure 2: Visual representation of an empathy gap between an autistic person and a non-autistic person

Although the double empathy problem was first presented in the context of autism, it can be applied to other forms of neurodivergence, and indeed other social groupings. For example, a person with ADHD might interrupt their non-ADHD conversational partner because they are excited, and yet their non-ADHD conversational partner might interpret that action as impatience. Even if you are not neurodivergent, you can likely recall a time you felt misunderstood by someone who had experiences and viewpoints that differed from your own.

Recently, Sebastian Shaw et al. (2023) proposed a triple empathy problem. Applied to education, the triple empathy problem arises when there is both a neurotype mismatch (e.g., autistic versus non-autistic) and a role mismatch (e.g., teacher versus student). Communities should strive to identify empathy gaps as they arise and reduce any inequalities in their impact. This might begin by asking questions like, how can I cultivate safety, comfort, and authenticity in my interactions with people who are members of different groups than me?

Neurodiversity movements can help us to dispel neuromyths.

Educational neuromyths are misconceptions about how the brain works and how this affects learning (Marta Torrijos-Muelas et al., 2021). Neuromyths have been observed in educators, healthcare professionals, parents of neurodivergent children, children, and the wider community (Silvia Gini et al., 2021). Neuromyths are harmful because they can reinforce stereotypes and associated stigma, and can result in misidentification or a complete failure to identify neurodivergence (Patrick Corrigan & Amy Watson, 2002).

There are many neuromyths about forms of neurodivergence; some examples include “autism is a learning disability”, “all autistic people have special abilities”, that ADHD can be cured by supplementing the diet with vitamins, that ADHD means the brain is over-aroused, or that mental capacity is hereditary and cannot be changed by the environment or experience (Marta Torrijos-Muelas et al. 2021).

Although the impact of neuromyths on teaching practice is unclear (Brenda Hughes et al., 2022), some research has examined the extent to which educational professionals endorse neuromyths. In their study of general population members and people working in education from preschool to higher education (including administration staff, inclusion managers, and mainstream teaching staff), Silvia Gini et al. (2021) found no difference in neuromyth endorsement between the general population and educational professionals. And, reported familiarity with neurodivergence was not associated with greater knowledge. Neuromyths related to autism were recognised more by teachers rather than neuromyths about ADHD, Downs Syndrome, and Dyslexia. Silvia Gini et al. (2021) suggest that this may be linked to campaigns and government initiatives for raising awareness of autism which suggests more work needs to be done with raising awareness and increasing knowledge of other forms of neurodivergence.

Given that neurodiversity paradigms can decenter dominant approaches to forms of neurodivergence, neurodiversity movements can create novel avenues for research, ultimately helping us to dispel neuromyths and cultivate epistemic justice.

How Might We Create a Neurodivergent-Friendly Ecosystem?

Before describing ways we might move closer toward a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem, it is important to acknowledge that achieving complete neuroinclusion is not easy. Individual teachers (and indeed their schools) are inherently subject to multiple competing contingencies, i.e., they are embedded in a larger social structure and interconnected with other domains that indirectly impact them.

In examining teachers’ views of systemic support within their schools, Stuart Woodcock and Lisa Marks Woolfson (2019) reported that leadership support, professional development opportunities, and adequate funding were deemed vital to support inclusion. Stuart Woodcock and Lisa Marks Woolfson (2019) also noted that participants felt that other teachers’ rigidity and unwillingness could undermine inclusion efforts, with some teachers reportedly framing inclusivity as a mere increase in workload for them.

Yet, importantly, we do not know what a true neuroinclusive classroom looks like. As Dinah Aitken and Sue Fletcher-Watson (2022) ask, “How much of the difficult behaviour teachers struggle with in class right now is motivated by children trying to hide their difficulties, or push adults away because they don’t feel they can be trusted?”. What if true neuroinclusion meant a reduction in overall workload? And, even if it does not, how can we create environments that support systems being inclusive anyway? Neuroinclusion requires systemic change. We cannot mandate that neurodivergent people conform to a neuromajority. Rather than always asking neurodivergent people to change to accommodate their environments, we should explore ways to change environments to better accommodate and support neurodivergent people. And, we cannot leave individual teachers to do this work without adequate compensation, resources, training, and support from the broader ecosystem. We need a neurodiversity-affirming systems approach.

Given the scope of this chapter, it is neither possible nor appropriate to give specific recommendations for accommodating and supporting particular neurotypes. Instead, we present strategies for becoming more neurodiversity-affirming in general.

Creating a Neurodivergent-Friendly Ecosystem: The Classroom

As part of the microsystem, a child’s classroom has one of the most direct, immediate impacts on their development. As best they can, teachers should familiarise themselves with neurodiversity and its associated paradigms and movements, ultimately striving to be neurodiversity-affirming. Additionally, because lack of understanding and stigma are key contributors to inequality, teachers could introduce all students to the concepts of neurodiversity and double empathy (Alyssa Alcorn et al., 2024).

The LEANS (Learning About Neurodiversity at School) programme is one freely available whole-classroom resource that may be used to teach children aged 8 to 11 years old about neurodiversity (Alyssa Alcorn et al., 2022). Through videos and teacher-delivered activities, LEANS aims to inform staff and children about neurodiversity, increase positive attitudes towards neurodivergent people, and increase inclusive actions within the school community (Alyssa Alcorn et al., 2022). Reesha Zahir et al. (2024) reported that LEANS received a high level of support for its usability, acceptability, and usefulness from survey respondents, 50% of whom reported experience working in education. Alyssa Alcorn et al. (2024) found that children who participated in LEANS scored significantly above chance in the Neurodiversity Knowledge Quiz and reported significant increases in the likelihood of behaving in inclusive ways.

Alyssa Alcorn et al. (2024) also found that LEANS participants reported significantly lower agreement with LEANS-aligned beliefs (e.g., “In my class, most people are kind and friendly to people who are different than they are”). However, this unexpected finding was interpreted by Alyssa Alcorn et al. (2024) as suggesting that LEANS led children to think more deeply about their views of the classroom. Notably, one adverse event was reported during Alyssa Alcorn et al.’s (2024) study. This led the LEANS team to add further guidance for teachers about staff-student and staff-family conversations on neurodiversity. The team further emphasise the need for all classroom staff to be involved in safety planning and the need for agreed procedures for handling sensitive conversations. LEANS can be accessed at https://salvesen-research.ed.ac.uk/leans

Another freely available resource that teachers may use to inform their neuroinclusive practices is Catherine Crompton et al.’s (2024b) NEurodivergent peer Support Toolkit (NEST). Codesigned by seven neurodivergent young people (aged 13 to 15 years old) and nine adults who reported experience working with neurodivergent young people (Francesca Fotheringham et al., 2023), NEST aims to facilitate student-led peer support for neurodivergent children in mainstream schools. Preliminary evidence supports the feasibility and acceptability of NEST, with students reporting that peer groups facilitated friendships, fulfilment, and a sense of community (Catherine Crompton et al., 2024a). Although designed for older children, professionals working with younger cohorts of children may draw on NEST to generate ideas for activities that can be used in their settings. NEST can be accessed at https://salvesen-research.ed.ac.uk/our-projects/nest-neurodivergent-peer-support-toolkit

Beyond extant programmes, less structured approaches to neuroinclusion at a microsystem level might involve responding to children in ways that help them to develop a healthy sense of self. For example, being attentive and responsive when a child identifies how they think or feel, or understanding that a child is the expert of their own experience (Alison Stapleton and Louise McHugh, 2021). As discussed above, each of our nervous systems works differently. This means that we can experience the same sensory input in different ways. Professionals working with neurodivergent children must be mindful of the potential for distortion of neurodivergent people’s experiences. For example, a child who identifies a room as being too bright for them might be responded to with assertions that the lighting is fine. From this, the child may derive that they are too sensitive or that their experience can be disregarded so long as the environment is fine for others. This distortion of the child’s experience hinders self-advocacy and could be understood as a form of sensory gaslighting that promotes masking (suppression of authentic responses in favour of alternatives). Professionals need to understand that nervous systems work differently and avoid mandating neuroconformity. Being neurodiversity-affirming is about ensuring each child has a comfortable journey and reaches their destination safely; it is not about cramming children into a non-stop shuttle bus headed for society’s destination of choice. Other frameworks, such as Mary Doherty et al.’s (2023) Autistic SPACE or Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2024), may also be useful for professionals seeking less structured approaches to neuroinclusion at the classroom level.

Creating a Neurodivergent-Friendly Ecosystem: The School

At school-level, recommendations from Marion Rutherford and Lorna Johnston (2019) that were highlighted by Dinah Aitken and Sue Fletcher-Watson (2022) include (i) reducing or eliminating the burden of school uniform policies and (ii) not ringing a school bell between classes. Schools may also create sensory-friendly spaces and flexible classroom setups. Given their “whole school” approach, each of these actions may benefit neurodivergent students who have sensory processing differences, including those who have not been formally identified as neurodivergent.

As part of the mesosystem, schools house myriad relationships and interactions between microsystems, such as teacher-parent interactions, teacher-teacher interactions, teacher-psychologist interactions, and many more. To help create a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem, teachers could avoid ableist language and challenge neuronormativity within these interactions.

For example, if contributing to a School Support Plan or Individualised Education Program, regardless of whether the child has been formally identified as neurodivergent, teachers could ensure stated goals do not reflect a normalising agenda that prioritises the comfort of the neuromajority at the expense of others (Kristen Bottema-Beutel et al., 2024). Teachers could also critically evaluate whether stated goals are truly measurable, unpacking any in-built neuronormative assumptions (Kristen Bottema-Beutel et al., 2024). In general, it can be helpful for teachers to reflect on apparent priorities; why is this goal being set? Who does this goal serve? What are the implications of this goal for the child? What alternatives are available? It can also be helpful to reflect on which knowledge bases inform our viewpoints (i.e., the child’s input, other teachers’ input, etc.).

As another example, if participating in identification processes for a neurodivergent child, teachers could report on the child’s struggles honestly and gently, with respect and compassion. This is particularly important when children are identified solely per pathologising models and when formal identification is the only pathway to accommodations and support. In this way, neurodivergent struggles are not erased and dignity is respected, reflecting a needs-affirming, rights-respecting approach.

Creating a Neurodivergent-Friendly Ecosystem: Beyond the Classroom and School

Expanding our focus to exosystem elements, many professionals use the DSM-V and ICD-11 to identify neurodivergent people. As such, these classification systems are often included in curricula for trainee teachers in higher education. If other approaches are not included, then trainee teachers’ understanding of neurodivergent people may lack important nuance. For example, they may adopt medical model ideology (e.g., that a neurodivergent person just needs to be “fixed”) and neglect alternative viewpoints (e.g., that unaccommodating and unaccepting environments need to be fixed).

Adopting a participatory approach to the co-design of neurodiversity-affirming modules in initial teacher education can help to ensure that curriculum content reflects multiple viewpoints and challenges neuronormative standards, stigma, and discrimination. Per EST, neurodiversity-affirming training in initial teacher education may mobilise neurodiversity narratives in our educational environments and communities, thus contributing to social change. For example, training educators to recognise, support, and actively sustain neurodivergent “ways of being” can lead to more effective teaching strategies and promote acceptance.

Across disciplines (e.g., teaching, nursing, psychology, etc.), one area of development seems to be ensuring that training curricula include examples of neurodivergent people’s lived experiences in different topic areas with educational opportunities including case studies and live simulations (where actors would role-play with students to support their learning). One example of how this could be done is Margaret Quinn and Sallie Anne Porter’s (2023) curriculum immersion for pediatric nurse practitioners where content about autism was embedded into existing topics to increase the knowledge and skills of nurses working with autistic people. Curriculum immersion offers a good opportunity to think about how we understand neurodivergence and the language used when sharing information about neurodivergent people regarding assessment and support. Below are extracts of assessment diagnostic formulations describing one form of neurodivergence (autism). Two versions are presented, one more pathologising than the other. When looking at the extracts, reflect on the language used.

- How might each formulation inform your understanding of the child’s strengths and support needs?

- How might each formulation translate to the classroom? What resources may be needed?

- How might you have a conversation with the child and/or their family based on the information shared? Does the type of language used make it easier or more difficult for you to have those conversations?

Sample extracts of assessment diagnostic formulations. Adapted by Nicola Ryan from an example used in assessment by the National Autistic Society UK.

| More pathologising description | Less pathologising description |

|---|---|

| Different, perceived as odd or a loner. | Bob reports feeling different from his peers in many ways. He does not enjoy school and notes finding many aspects confusing, especially navigating social relationships. Bob believes that his peers misunderstand him and feels as though he needs to pretend to be someone else in order to fit in. Bob likes spending time with people, particularly in a one-to-one setting and has enjoyed spending time in group settings when he could rest and recover afterward. |

| Social communication difficulties, pedantic, inflexible | Bob presents as a precise communicator. He enjoys language and particularly likes to focus on accurate detail. Bob speaks passionately about things he is interested in and reports struggling to focus and maintain interest when other conversation topics arise. Bob is most comfortable with unambiguous, straightforward communication styles. |

| Obsessive, restricted, and repetitive interests and behaviours. Hypo/Hypersensitive to his environment. | Bob is a naturally monotropic thinker and is at his best when he can focus on a topic in-depth, particularly without interference. Bob demonstrates good attention to visual detail and touch that allows him to enjoy painting and other arts subjects. Background noise or noises that he cannot explain can be distracting or even distressing for Bob, and Bob notes that his peers may not understand his experience. |

Our conceptualisations and the language we use to describe neurodivergent people matters because they can have a cascading effect across subsystems. Consider the potential implications of a neurodiversity-affirming healthcare professional preparing a report on a neurodivergent child’s support needs that will be shared with a neurodiversity-affirming teacher. How might outcomes for this child differ from those of a child who has a pathologising report shared with a teacher who has only learned about medical models approaches to neurodivergence?

Beyond improving curricula, other ways to create a neurodivergent-friendly ecosystem include conducting and addressing sensory audits of built and digital environments. For example, in Ireland, as part of the “Making UCD a Neurodiversity Friendly Campus” project, the University College Dublin Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Neurodiversity Working Group (2024) developed a sensory audit tool using data from their scoping review, gap analysis, survey, and qualitative interviews. The sensory audit included items assessing layout, signage, décor, lighting, temperature, and auditory, tactile, and olfactory experience. Across the audited areas, concerns included open-plan working environments, a lack of designated sensory spaces, and inconsistency in the use of accessibility features within the virtual learning environment. For another sample audit, see Paty Paliokosta et al. (2024).

Such audits can address all EST subsystems. Specifically, we can focus on the microsystem by improving the physical, emotional, and digital environments where students interact daily. Involving students in the audit’s creation strengthens the mesosystem, enhancing connections between different microsystems like students and administration. The audit also impacts the exosystem by influencing policies and practices, creating a more inclusive environment. It reflects societal values in the macrosystem by promoting neuroinclusion. And, finally, the audit’s iterative nature aligns with the chronosystem, ensuring the learning environment evolves to meet changing student needs. This comprehensive approach can foster a supportive and inclusive environment for all.

As we come to the end of this chapter, we invite you to return to our Example Case. Recall the neurodivergent child that has arrived at school after a hectic weekend. They have forgotten to bring their lunch, and one of their socks is on inside out. Their teacher asks them to correct misspelled words on a handout. How might we reduce the demands filling their capacity jug? How might we gently expand their capacity jug?

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- What fills your capacity jug? What helps you to gently expand your capacity jug?

- When have you experienced the “double empathy” problem, whether on the basis of your neurotype or another group membership?

- Reflecting on your professional training to date, what language do you tend to use to describe neurodivergent people?

- How can you help to create neuroinclusive communities?