Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Participation of Children and Youth in Learning and Community Development

Carlos Moreno-Romero; Ines Boban; Maryam Mohammadi; Shichong Li; and Silvia Dell'Anna

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Imagine a learning experience where young people become interested and engaged in their community’s nutritional well-being. Imagine a project where young people build a Zen Garden for their community to enjoy. Imagine a setting where young people make use of restorative to help their peers solve their conflicts through non-violent communication, active listening and restorative questions. These are some examples that point to the importance of involving young people in decision-making within their communities and their learning experiences.

Example Case

“As a student at the Participatory School, a humanistic, democratic school, we were always encouraged to explore new topics through a project-based learning method. From a young age, we undertook individual projects on subjects that interested us, examining them from multiple perspectives and deepening our understanding. During secondary school, we embarked on a collective project that involved community participation. The school proposed several topics, and we chose to focus on the issue of malnutrition among children in our country.

Our first step was to conduct thorough research on malnutrition and its significance. We discovered that the prevalent form of malnutrition in our country is due to a lack of essential vitamins and minerals. Understanding this, we recognised the need to learn about the effects and consequences of vitamin deficiencies. Each of us researched one or two specific vitamins and shared our findings with the group. We knew that we needed to be well-informed to raise awareness and drive change.

To involve the community, the first step was to ask all students and their parents to participate in comprehensive blood tests to measure vitamin levels. Over two months, nearly 150 families took part, allowing us to analyse their blood tests and identify common deficiencies. Our research indicated that given the economic conditions, simple dietary changes like drinking a glass of milk and eating two eggs daily could help address these deficiencies.

Next, we needed to disseminate our findings to children, their families, and schools. We attempted to collaborate with the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education to implement new policies in schools, but not all efforts were successful. Therefore, our plans changed, and we had to develop a new initiative to raise awareness. Realising the importance of trust, we decided to engage well-known artists, actors, and singers in our awareness campaign. These public figures were photographed with a glass of milk, and their images were displayed in a large photo exhibition and shared on their social media, reaching a wide audience.

We also expanded our efforts by sharing our project with similar groups in other cities, aiming to raise awareness nationwide. The project has since grown into a larger online initiative where people across the country share nutritious recipes and food tips.

Currently, I have stepped back from direct participation in the project, allowing others to take over. What I have learned is that scaling a project does not require the original members to remain in control or be actively involved until its completion, and it was one of the principles that the school wanted us as students to learn. Stepping aside from a project that you have started and witnessing others continue allows the project to thrive and achieve its main objectives, such as the principle of participation, more effectively.”

Baran Yousefi, former student of a democratic school in Tehran, Iran

The example above comes from the Participatory School in Tehran, Iran. It is important for readers to understand that, while this school provides an extraordinary and inspiring example of participatory education, it is not representative of the broader educational landscape in the country. The innovative practices and values at this school stand out as a unique model, differing significantly from the more conventional approaches found in many other schools in Iran.

The Iranian Ministry of Education does not recognise the Participatory School, although it has demonstrated significant achievements. It aims to promote a variety of educational methods, rather than endorsing a single official approach, across the country. It seeks to inspire change by offering alternative models of education that prioritise participation and diversity in learning methods.

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What are the guiding principles/concepts for meaningful participation of children and youth in learning and community development?

- What hinders the participation of children and youth in learning and community development?

- How do we facilitate the participation of children and youth in learning and community?

- What are the possible next steps for students and teachers?

Introduction to Topic

In today’s rapidly changing world, children and youth are often positioned as passive recipients of education rather than active participants. However, there is growing recognition of the importance of engaging young people in both their learning and the development of their communities. This shift moves beyond traditional classroom boundaries, positioning children and youth as essential contributors to societal progress.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) emphasises that young people have the right to participate meaningfully in decisions that affect them. Consisting of 54 articles and ratified by 196 countries, the UNCRC defines children’s participation as an “ongoing process that includes information-sharing and dialogue between children and adults, based on mutual respect, where children learn how their views and those of adults are considered and shape the outcome of such processes” (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009).

This means fostering environments where their voices are not just heard but are actively considered and integrated into outcomes that shape their lives. In both educational settings and broader community contexts, participation is a robust process that empowers children and youth to take ownership of their learning, build leadership skills, and contribute to creating more equitable and just societies.

To see school as the ivory tower of learning would be limiting. The title of the chapter contains the term ‘community development’, clarifying the importance of extending action to the whole society. Full and meaningful participation transcends the walls of a classroom. It reaches outward to integrate knowledge and other perspectives and contribute politically, socially, and culturally so that children and youth can truly assert themselves and perceive themselves as citizens.

In this chapter, we explore the guiding principles that promote meaningful participation of children and youth, examine the barriers that hinder their engagement, and discuss strategies to foster their active involvement in learning and community development. Through examples and case studies, we will illustrate how, when empowered to make decisions and engage in collaborative processes, young people can transform their roles from passive learners to active changemakers – active with full children’s rights.

By drawing on theoretical frameworks and practical case studies, we aim to uncover the transformative potential of child and youth participation. This chapter seeks to challenge traditional power dynamics between adults and children, advocating for an egalitarian approach to education and community development. Whether through student-led initiatives, participation in decision-making, or collaborative community projects, we will highlight the many ways in which children and youth can be powerful agents of change when given the opportunity.

Participation in action: principles, power dynamics, and areas for development

What do we mean by “participation of children and youth in learning and community development”?

Baran’s example highlights how children’s roles can shift dramatically when given the opportunity to participate actively. No longer confined to the traditional role of a student passively absorbing information, Baran took part in a community research project, where she contributed her knowledge to address real-world issues. Through her involvement, Baran not only demonstrated her ability to acquire scientific knowledge but also played a crucial role in improving her local community. She became an active agent of her own learning, shaping the process and outcomes of her educational experience.

By examining Baran’s story, we challenge the conventional stereotypes of children as passive learners. Instead, we emphasise that learning extends beyond the classroom and occurs wherever children are no longer restricted. Children like Baran can be active participants in both their education and community development, initiating projects and contributing meaningfully to societal change.

Addressing power imbalances and recognizing children’s agency

The persistent power imbalance between adults and children has long limited the participation of young people in important decision-making processes (James, 2007). However, recent work in the sociology of childhood aims to dismantle these power dynamics. Scholars are now focusing on demystifying the relationships between children and adults, advocating for the recognition of children’s capabilities and their right to participate actively in various settings (Mayall, 2013).

As awareness of children’s potential continues to grow, it is crucial to adopt a balanced approach that neither underestimates or overestimates their abilities. Children and youth should be seen as competent individuals whose contributions deserve fair recognition and integration into broader social structures. By embracing this balanced perspective, we can create more equitable and inclusive environments where the voices of children and youth are not only heard but also valued. This shift paves the way for a more just and participatory society, where young people play a central role in shaping their communities and futures.

It is the responsibility of teachers, along with their broader network of stakeholders, to critically analyse potential risks and boundaries in any participatory process, ensuring that no harm is caused to students or their communities. This should be done collaboratively with students, as it is essential to equip them with the skills to identify and understand these risks. Teachers must be especially mindful of issues such as privacy and data protection, particularly when projects involve online presence or public platforms. For example, safeguarding personal information and implementing measures such as comment restrictions on social media platforms can help protect students from negative exposure. This process of risk assessment should be ongoing, responsive to the specific context, and always prioritise the well-being and safety of students, ensuring that participation remains a positive and empowering experience.

The rationale for promoting children’s and youth’s participation

There are numerous benefits to adopting a holistic approach to youth participation, which ultimately leads to stronger engagement in community development. Firstly, involving young people in decision-making and conflict resolution has enhanced their moral reasoning skills (Kohlberg, 1985). This process helps youth become more aware of their rights and responsibilities while also reducing school bullying – a behaviour often stemming from power imbalances both within and outside school settings (Gribble, 2016).

Furthermore, when children and youth are actively involved in creating agreements, it promotes the development of positive and functional boundaries, which are closely tied to inhibitory control (Juul, 2001). This involvement strengthens their sense of belonging to the school community (Hope, 2012), fostering a deeper commitment to their own learning, reducing anxiety, and facilitating autonomy and self-regulation (Anderman, 2002).

In addition, when young people are seen as key contributors to school management, their argumentative skills and academic performance tend to improve (Bouché Peris, 2003; Day et al., 2009). It further contributes to the establishment of a participatory leadership culture, where everyone – students, teachers, and community members – develop the tools needed to influence their surroundings positively (Louis et al., 2010). Such experiences encourage young people to value diversity and cultivate a sense of social responsibility (Bruyere, 2010), while providing practical lessons in rights and responsibilities (Danner & Jonyiene, 2012).

Youth participation also plays a critical role in fostering citizenship skills. Learners who advocate for individual and collective rights develop empathy, political literacy, and an increased sense of responsibility for their actions (Hope, 2012). Prud’homme (2014) supports this view, noting that involving young people in decision-making and conflict resolution related to their education can promote respect for diversity and encourage greater civic engagement. These experiences empower youth and enhance their critical thinking, preparing them to be thoughtful and engaged citizens.

Moreover, children and youth have demonstrated their capacity to be active citizens in various ways (Loader et al., 2016). In Scotland, for example, young people are granted the right to vote at 16, a rare policy that significantly increases their political engagement (Huebner, 2021). This reform has given Scottish youth the confidence to express themselves in traditionally adult-dominated spaces. Schooling plays a crucial role in shaping these early voting behaviours, enabling young people to challenge power imbalances and address social inequalities. Research shows that early voting experiences in Scotland have led to higher voter turnout in subsequent years (Dinas, 2012; Huebner, 2021), underscoring the importance of democratic education in fostering long-term political engagement.

In conclusion, engaging children and youth in their learning and community development lays the foundation for their future contributions to society. Starting with small, meaningful changes, youth can be empowered to take control of their lives and participate more actively in shaping the world around them.

Key areas of participation for children and youth in learning and community development

Children and youth can engage in various areas of participation that foster their role in learning and community development. These areas include:

- Knowledge construction and critical reflection: Youth participate in critical discussions and research, collaborating with adults or independently, as seen in movements like Philosophy for Children and Citizen Science for Kids.

- Political power and decision-making: Initiatives such as Children’s Parliaments and lowering the voting age (e.g., in Ireland) empower children to influence local and school-level governance.

- Community contribution and social engagement: Programmes like Self-Directed Service Learning and the Learning City Model promote the integration of learning with community service and engagement.

- Tailoring education and learning participation: In democratic schools like Freie Schule Leipzig (Germany) and Summerhill (UK), children shape their learning by negotiating timetables and curricula, using tools like Learning Contracts and peer tutoring.

- Cultural initiatives and expression: Youth-led projects, such as radio stations, journals, and intergenerational learning programs, provide platforms for self-expression and cultural collaboration.

- Space design and environmental planning: Children collaborate (if needed with architects and planners) to create spaces that meet their needs, such as designing playgrounds or reorganising classrooms.

In these areas, participation must be ethical and meaningful, ensuring that children’s voices are respected and supported to engage effectively in issues affecting their lives.

Barriers to participation and strategies for empowering children and youth in learning and community development

Navigating power dynamics: ensuring equitable participation in education

The relationship between teachers and students in traditional educational settings is often shaped by power imbalances. Teachers are typically seen as the sole bearers of knowledge, while students are viewed as passive recipients. This creates a hierarchical structure where students have little control over their learning experiences. In specific social contexts, teachers’ knowledge, along with their embedded authoritarian positions, can appear oppressive to children as students, resonating with an inequality that manifests in the power dichotomy.

The philosopher Michel Foucault (1982) famously argued that “knowledge is power,” a concept that applies to the teacher-student relationship. In many classrooms, teachers’ control over knowledge reinforces their authority, limiting students’ agency. Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1970?) took this idea further, critiquing traditional education systems where teachers act as oppressors and students are merely passive learners. However, teachers represent the system and society as a whole and do not just act as oppressors on their own initiative.

Freire (1970) advocated for a “liberatory” approach to education – one that empowers students to recognise their own potential and make meaningful contributions. In this model, teachers act not as authoritarian figures, but as facilitators who guide students in shaping their learning experiences. By shifting away from hierarchical structures, we can create a learning environment that fosters genuine participation and collaboration.

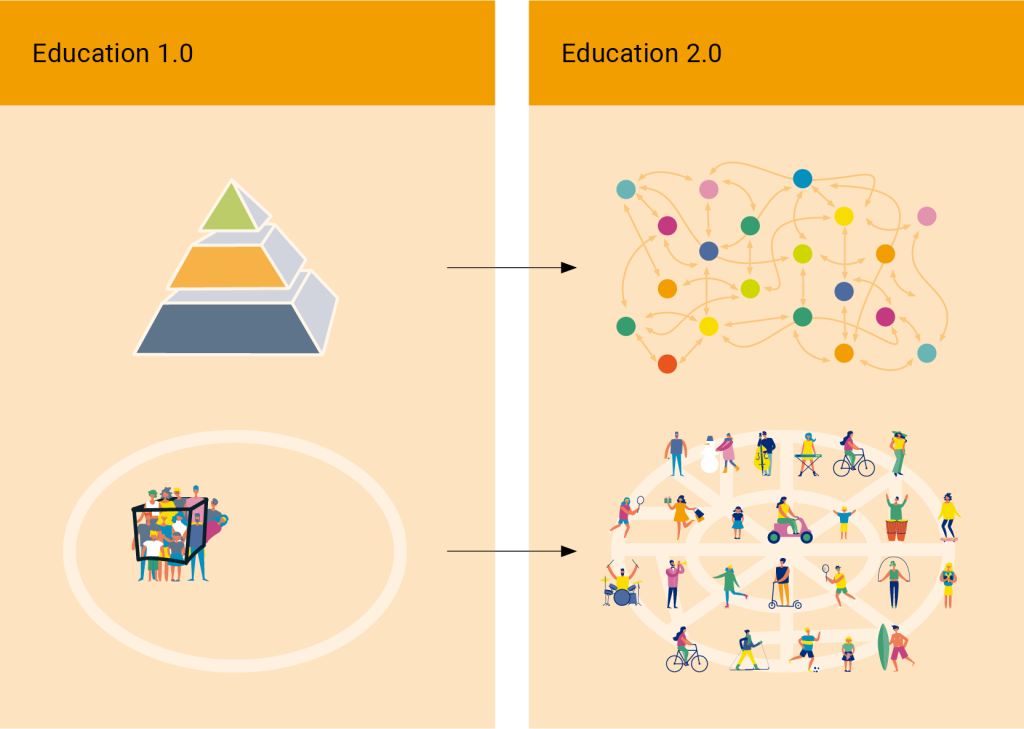

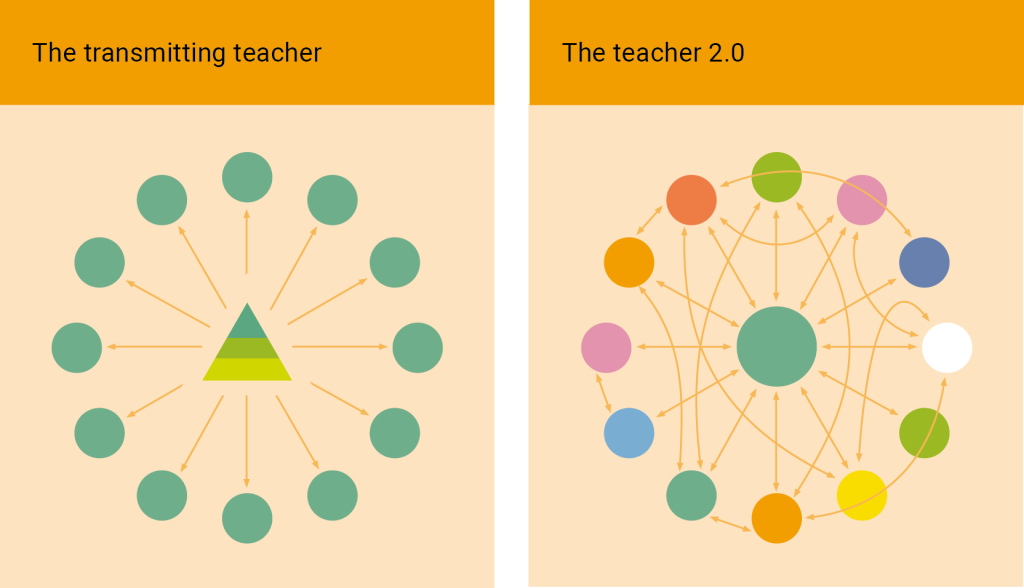

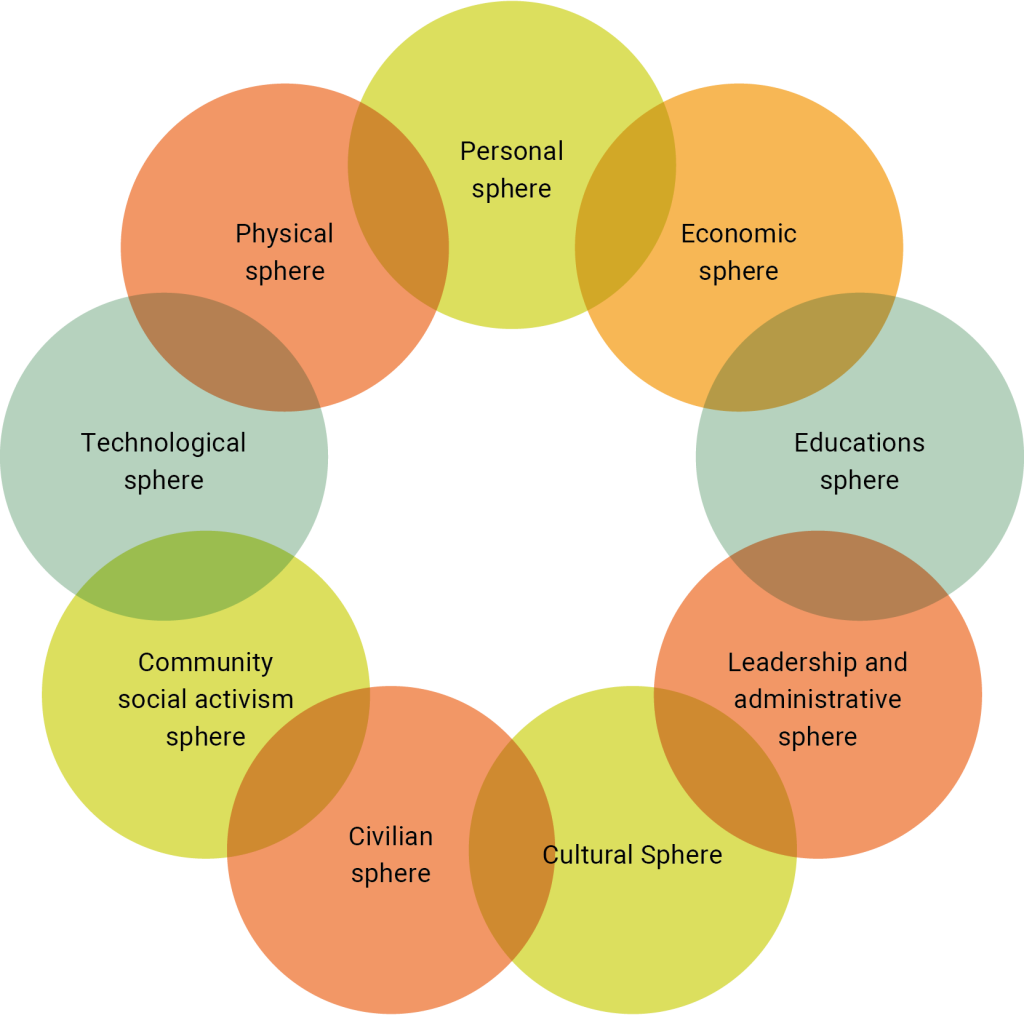

In democratic schools, learning is seen as a collaborative process. Rather than being arranged in a pyramid, where teachers sit at the top and students at the bottom, democratic schools operate more like interconnected circles (see Figure 1). Each “circle” consists of participants—students, teachers, and community members—working together as equals. This approach decentralises power and encourages shared responsibility in decision-making.

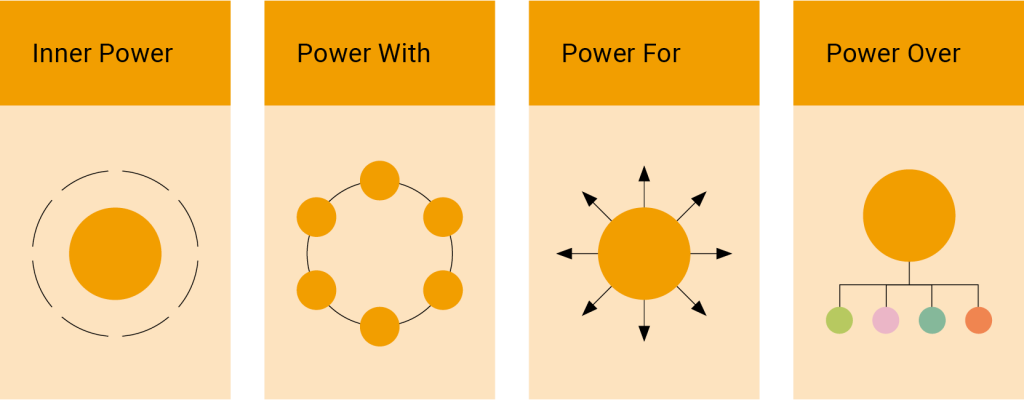

Figure 1: From traditional to democratic and inclusive education – or: from Power over to Power with

Similarly, starting with the identification of student-teacher power disparity, teachers and other practitioners can then tailor their strategies accordingly to empower children and youth through their learning in school and engagement in community development, which, in turn, can positively influence the ways learners become agents of learning, making changes to their learning in school alongside teachers. As children and youth are regarded as active participants in their own learning by taking part in curriculum decision-making, teachers and other adults become facilitators, rather than superior or dominant leaders of children’s and youth’s participatory learning.

In addition to addressing the general power imbalance between teachers and students, educators must also be mindful of the power dynamics arising from differences in gender, sexual orientation, economic, social, and cultural background, class, dis/ability, race, languages, health, age, pregnancy and early parenthood, belief, religion (or lack thereof), biography, and appearance. These differences often intersect, shaping the way individual students experience education and access opportunities. It is crucial for educators to ensure that representation reflects this diversity, creating spaces where underrepresented minorities can express their voices without placing the burden on individual students to represent ‘their’ minority group. Schools must create an inclusive environment that promotes equitable participation by actively addressing these imbalances, ensuring that the experiences of marginalised students are acknowledged and valued, and that structures are in place to support their contributions to learning and community development.

Having real decision-making power

Involving learners in decision-making processes within conventional schools comes with certain risks, particularly when their participation is limited to surface-level involvement. Often, schools allow students to express their opinions on pre-determined topics, but these topics are carefully controlled, giving students little real power to influence decisions (Taylor & Percy-Smith, 2008). This creates a “passive participation” model, where young people are consulted or represented, but their ideas are easily manipulated or shaped by adults (I’Anson, 2013). In such models, students may feel they are being heard, but their contributions rarely result in meaningful changes. This can limit their ability to generate new ideas and force them to conform to decisions favoured by social pressure or the school’s pre-existing agenda (Hecht, 2010; Thornberg, 2010).

On the other hand, Huang (2014) argues that schools need to address the contradictions between promoting a participatory approach and the societal structures they exist within. Many schools claim to encourage student involvement, but their practices often reflect the hierarchical and undemocratic structures of the larger society. This can either alienate students from participating in real decision-making or prompt them to question the inequities and power imbalances around them. When young people recognise these contradictions, it can empower them to challenge social hierarchies and outdated systems that limit their ability to fully engage as equal participants in both their schools and communities.

Ways of change – needs for (un)learning/changing the narrative to shape the future

Changing the future requires changing the stories we tell ourselves, as these narratives shape and structure our mindsets (Korten, 2015). Many of the dominant narratives we encounter sound like: “Hurry up, be quick, and meet the standards!” or “Time is money, so be fast and efficient!”. These narratives drive much of how we live our lives today. But by reflecting on their impact, we can begin to explore alternative stories, such as: “Time is life, and it’s meant to be shared.” This shift in thinking can transform how we structure our daily lives, marking the start of an unlearning process.

In education, this unlearning involves decolonising schools and moving away from serving the needs of corporations that position today’s children as future workers (Black, 2010). It requires abandoning standardised curricula, hierarchical relationships, and training programmes focused on skills suited for the global economy rather than local or regional needs. Instead, education should emphasise community-driven, place-based learning, moving away from the idealised notions of “development” and urban consumer culture (Norberg-Hodge, 2019).

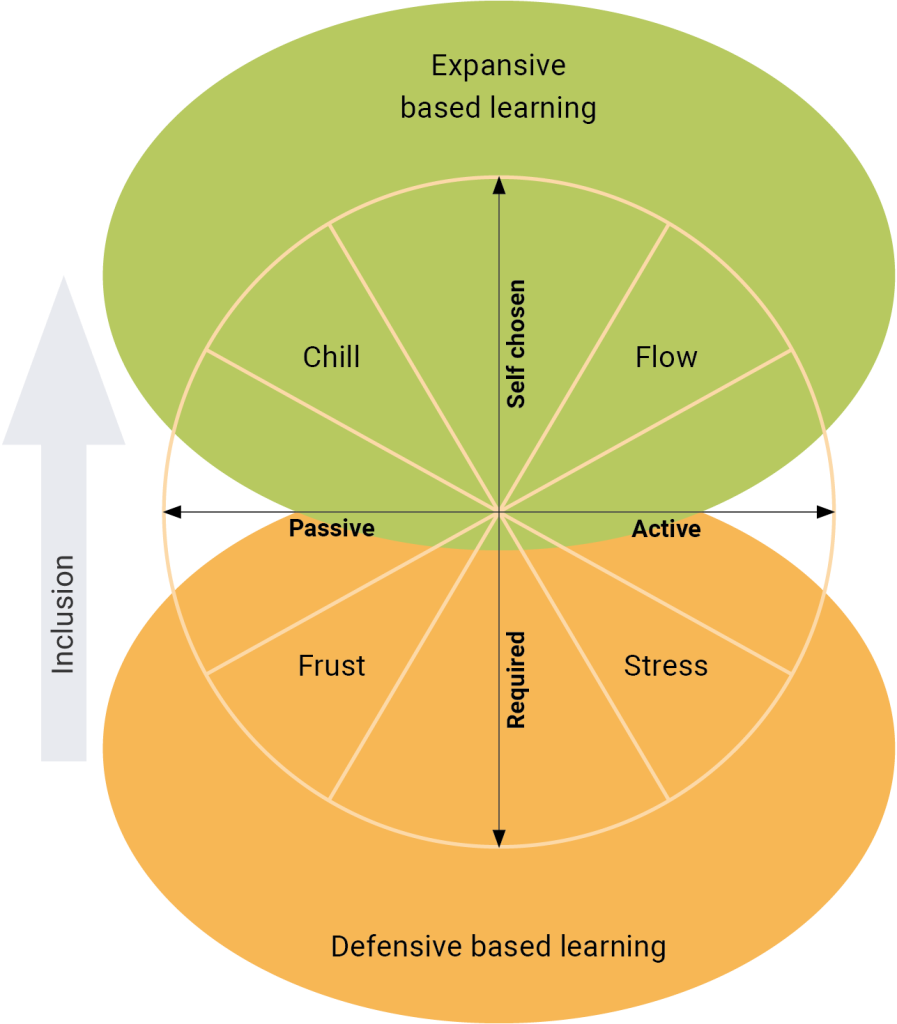

A critical step in this unlearning process can be found in concepts like “Deschooling Society” (Illich, 1999) and Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (1970). These approaches emphasise recognising the structures that restrict participation and limit learning. Furthermore, critical psychology (Grotelüschen, 2005; Holzkamp, 1995) highlights two distinct modes of learning: defensive and expansive, both of which can be applied to inclusive education.

Defensive vs. expansive learning: A compass for education

The defensive mode is what many children and youth experience within conventional school systems, where they are focused on managing frustrations and stress, simply trying to survive within the institution (Figure 2). This type of learning, unfortunately, becomes their default as they leave school and enter the world. In contrast, the expansive mode – rare in most schools but a basic human right (as enshrined in Articles 12 and 24 of the UNCRC) – is characterised by moments of deep engagement and self-directed inquiry. Here, learners are free to explore self-chosen topics, allowing their curiosity to flourish. This process nurtures both the mind and the soul, offering opportunities to grow beyond the constraints of defensive learning.

Figure 2: Compass for inclusive education

The future of inclusive education lies in expanding opportunities for this kind of expansive learning, while reducing defensive learning environments. It is essential that we reflect on how our own educational experiences have shaped our expectations – of ourselves and others – and recognise the importance of creating spaces for expansive learning, especially in schools.

The role of expansive learning in life and community

The contrast between defensive and expansive learning is not limited to schools – it is crucial throughout our lives. It begins in early childhood and continues through years of schooling. However, it needs to extend beyond the classroom, so that everyone can become active participants in their local and global communities. As shown in the earlier examples, engaging in expansive learning can lead to fundamental changes in how we interact with the world, particularly when addressing contemporary ecological, economic, and social challenges.

This shift in the narrative also requires rethinking the popular phrase “It takes a village to raise a child”. In today’s world, we need to transform this into “It takes children to raise the village (or community)”. This means moving away from the adultist perspective (Flasher, 1978) that views children as incomplete or not yet capable, and instead recognises them as competent experts of life. Citizenship is not something to be earned, but a right every person is born with.

Unlearning ageism and embracing children’s participation

One of the key elements in changing this narrative is to unlearn ageism – the belief that children are incomplete beings who need education to become “real” members of society. This mindset denies the inner potential of children and youth, limiting their ability to participate fully in decisions that affect their lives. In fact, research shows that even newborns are learners, filled with awareness and empathy (Wagenhofer, 2015). Therefore, it is time to recognise and nurture the inner richness of each child, ensuring that this potential is maintained as they grow into youth.

In a project to develop all-day schools in Germany (based on the Index for Inclusion; Booth & Ainscow, 2011), many adults initially doubted the capacity of younger children to participate in school development. While students in grade 4 of primary schools were seen as competent and capable, these same students were viewed as too young and overwhelmed when they transitioned to grade 5 in secondary schools. This inconsistency reveals a common logic in schools, where students are constantly seen as ‘not yet competent’ until they reach the next level (Hinz et al., 2013). However, this view is increasingly challenged, especially by the democratic participation of children, even in kindergartens.

Unlearn to have power over – change the story to other ways of being powerful

The means by which we view the idea of power hinders the participation of children and youth. Some alternatives such as those from the Global South (Brown, 2018; Just Associates, 2006; Ryland, 2024), create spaces by focusing on the ‘inner power’. The example of the participatory school in Tehran describes the role of power in different contexts (see Figure 3):

- inner power in all of the members; when they start to use it, it becomes synergistically a

- power with others, to think about the changes they need in the place, because it is obvious that something has to become better than it was. So, they create the

- power for specific processes, not changing everything, but raising awareness for and together with companions on key issues, taking over in situations that first seem to be quite powerless – especially where others try all the time to be dominant and have

- power over what is going on and keep it in their hands. This means that now we learn that it is possible to find ways to use power in a different way.

Figure 3: Four ways of power

Everything begins with the aspect of the ‘inner power’ – something only individuals can minimise or maximise. Once this ‘inner power’ appears, and finds an expression, it can become a ‘power for’ others too, and when shared, it may become a ‘power with’ for common engagement purposes for a better future related to ecological and social topics of our time. Finally, there is a ‘power to’ realise essential changes.

In a democratic education model, children and youth are no longer seen as passive objects shaped by curriculum designers, architects, or city planners. Instead, they are active participants – subjects in their own right – who bring expertise and creativity to the table. This shift moves participation from being a “nice-to-have” opportunity granted by adults to a fundamental right guaranteed for everyone (Jörgensdóttir Rauterberg & Hinz, 2025). In democratic schools, such as those illustrated by Hecht (2017), the traditional power dynamic of “education 1.0” – where adults hold power over students – is replaced by “education 2.0”, where students, teachers, and the community share power and work together for collective learning and development in a “partneristic” way (Eisler, 2001).

This approach is reflected in projects like the Inclusive Neighborhood Children’s Parliaments in India (Kersting, 2018) and the Barefoot College in Rajasthan, where children and youth take on leadership roles in their communities. These examples demonstrate how shared power – power with – can lead to more inclusive and democratic processes in both education and community development. As we continue to explore ways to promote child and youth participation, these models provide a roadmap for moving away from hierarchical power structures toward more collaborative, empowering forms of engagement.

Unlearn hierarchical schooling – learn to develop learning places in a participative process

Janusz Korczak once said: “To repair the world is to repair education”. In a time when schools face teacher shortages and solutions often involve increasing class sizes or cutting parts of the curriculum, it is more urgent now than ever to rethink the role of teachers. The traditional model, where teachers hold power over their students and simply transmit knowledge, must give way to a more participatory approach.

Figure 4: The transmitting and the connecting role of teachers

In the old model (illustrated on the left side of Figure 4), teachers control the flow of knowledge and shape students to fit their own ideas, much like filling them with information to match a set standard. However, the right side of the diagram demonstrates a more inclusive role for teachers, where each person (teachers and students alike) become both a learner and a teacher. This shift marks the beginning of what Korczak described as the proper repair of education, where learning is not hierarchical but collaborative and shared.

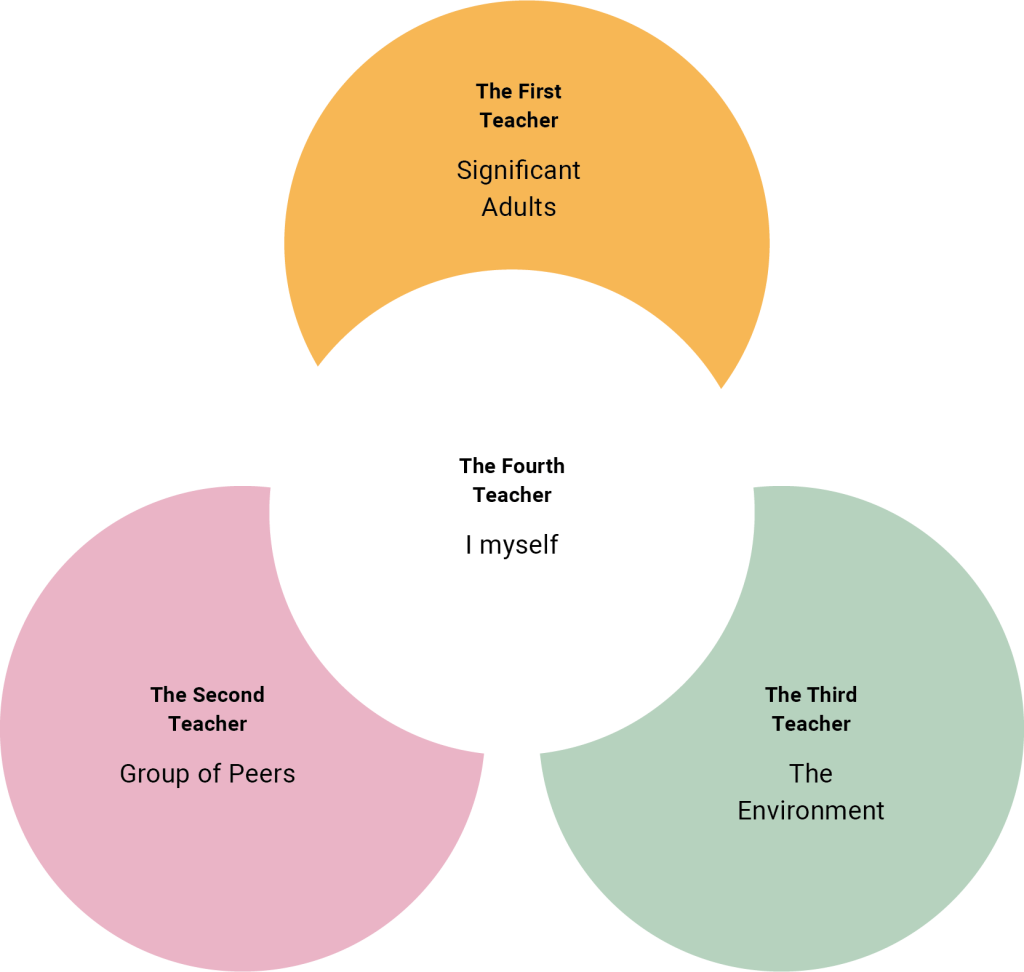

This concept of shared learning is reflected in the idea of the “Four Teachers” (illustrated in Figure 6). These four learning forces—teachers, learners, peers, and the environment—need to be integrated into learning spaces to bridge the gap between education and democratic processes. By doing so, we create fertile ground for genuine learning in a humanistic and participatory way. In the face of today’s global challenges—ranging from climate change to cultural erosion – this transformation is not just idealistic, but necessary.

To truly repair the world, we need to unlearn the models of corporate globalisation that have shaped education for the needs of the global market. These models prioritise standardisation, competition, and economic goals over the well-being of local communities. Instead, we must create spaces where people engage in addressing local issues and develop solutions that reflect the needs of their own environments. As Helena Norberg-Hodge (2019) argues, “local is our future”, and empowering communities to take control of their own education systems is a key step in this direction.

A good example of how this can be achieved comes from the film “Power to the Children” by Anna Kersting (2018), which portrays children and youth in India taking control of their communities’ future. By establishing children’s parliaments and electing their own ministers, these young people are not only standing up for their rights, but they are also creating lasting change in their communities. They are addressing issues like environmental degradation, standing against social injustices, and implementing practical solutions—such as reducing plastic waste, conserving water, and promoting recycling.

This kind of participatory action demonstrates the transformative potential of empowering young people to take part in shaping their own futures. When children and youth are given real opportunities to engage with their communities, they are not just learners but leaders, activists, and agents of change.

Unlearn the “boxes” of traditional education: embracing localities and place-based learning

As Helena Norberg-Hodge (2019: 55) asserts, “Societies in both the Global North and South would benefit enormously from a shift away from corporate-tailored curricula towards diverse forms of place-based learning”. Instead of adhering to outdated models that prepare students for a corporate-led, competitive economy, Education 2.0 must be tailored to the unique environments, cultures, and local economies of each region. This shift promotes local sustainability by emphasising regional agriculture, traditional architecture, and decentralised, low-tech solutions for meeting basic needs.

For years, community organising has been a key element of democratic engagement, and can serve as a powerful model for Education 2.0. Community organising teaches people how to bring about social justice and ecological sustainability – critical lessons that schools should also embrace (Meier, Penta & Richter, 2022; Penta, 2007). By adopting these principles, schools can become part of place-based learning circles, focusing on solving local challenges while fostering active student and community participation. This holistic approach would empower learners to move beyond seeing themselves as “victims of the market” (Kumar & Haworth, 2022) and instead become active agents in reshaping their environments.

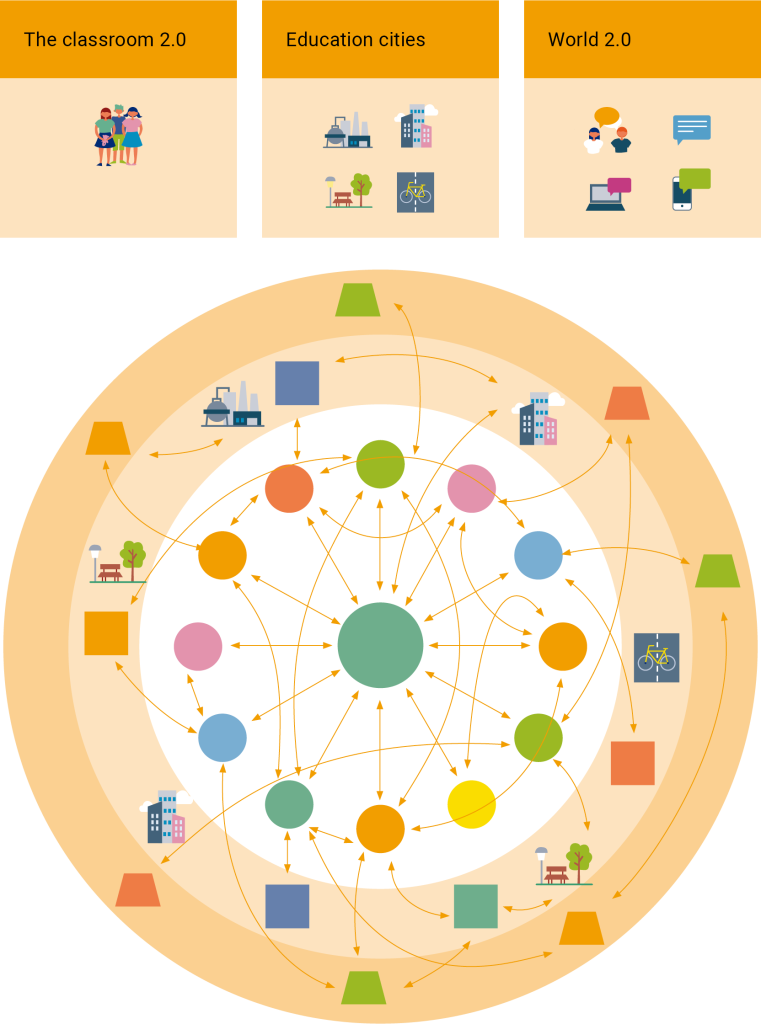

The concept of the “Education City”

If a city chooses to adopt the model of an Education City, it first unlearns the traditional idea of separate, isolated “little boxes”—an idea that more fitting to the industrial age, when hierarchical structures reduced complexity. Instead of this old model, the Education City embraces interconnected circles of learning, encompassing the classroom, the community, and the world (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Learning 2.0: Children and youth in classroom, community and the world

In an Education City, all members of the community – mayors, citizens, teachers, and students – are responsible for fostering learning in these circles. As described by Schwartzberg and Dvir (2012), this concept introduces the idea of the Four Teachers as shown in Figure 6:

- The first teacher is individuals’ interaction with significant adults throughout their lives.

- The second teacher is the experience gained through peer group interactions over time.

- The third teacher is the environment itself, where learning happens through connection with the world.

- The fourth teacher is the individual, who learns through the choices they make in their own life.

Figure 6: Four teachers

By embracing these Four Teachers, an Education City shares power in a participative way with children and youth, making learning a collective responsibility. But what does it mean for a city to “take responsibility” (Schwartberg & Dvir 2012: 12) for learning?

Taking responsibility for democratic education

In an Education City, the entire community takes responsibility for supporting democratic education and the development of all its residents in a humanistic and sustainable way. This means that all resources – whether educational, environmental, or social – are dedicated to the growth and well-being of everyone in the city. An ongoing dialogue about education is also be maintained, constantly evolving and adapting to promote twenty-first-century learning (Schwartzberg & Dvir, 2012).

Figure 7: The urban art of mixing colours

Such a city thrives on what can be called circle power. It moves away from the rigid, pyramidal structures of the past and embraces the dynamic, sometimes chaotic, processes of curiosity and creativity. This is not about simply reforming education by widening the traditional triangle into a neat square, rather the Education City unfolds like a flower, with multiple spheres of learning interwoven in a beautiful and complex system (see Figure 7).

In this model, citizens are encouraged to think and act outside the boxes of conventional education. By reducing the old patterns of hierarchical power, the Education City makes room for a more inclusive and democratic Education 2.0, where everyone, students, teachers, and community members alike, work together to create a better future. As the examples in this chapter will illustrate, moving beyond the old educational models is essential if we are to repair both our minds and the world we live in.

Life, after all, is time—and that time should include moments of both flow and reflection.

Examples of participation of children and youth in learning and community development across countries

The transition of learning processes for children and youth to enhance their potential to participate as much as possible differs from place-based. Therefore, it makes sense to highlight some examples of ways in which more shared powers can be found in various countries.

Children and youth’s participation in school management

The democratic participation of children must be considered from the viewpoint that all freedom is finite, and must also be viewed in relation to the coexistence and safety of everyone in the educational environment. Thus, in the global context of the lack of opportunities for student participation in school decisions, school self-government aims to fulfill the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1990), which highlights the urgency of supporting processes that allow children to develop and freely express their own opinions (Articles 12-15), and promoting spaces for children’s participation in decision-making on matters that affect them (Articles 12, 23, and 31).

In this sense, overcoming the paradox of instructing about democracy within non-democratic school structures and practices (Bridges, 1997; Stevenson, 2010), free and democratic schools[1] implement regular meetings framed within the body of the Assembly or Parliament and involving the school community, to decide on relevant issues for their coexistence such as school agreements, curricular topics, workshops to offer, graduation requirements, field trips and travel, visits to the school by experts, etc.

The ground agreements that govern such meetings are respect towards each other and turn-taking, taking others seriously while trying to understand the degree of truth they hold, and defending one’s own thinking without attacking others. Similarly, democratic schools share with Apple and Beane (1995) that “democratic planning is not about making use of the right to vote, but about the convergence of different points of view and the search for a balance between particular interests” (p. 25). In this regard, the role of the adult transforms from being a teacher (in charge of making learners learn something) to becoming a facilitator that scaffolds and supports young people’s guided appropriation of democratic practices. Within this setting, young people participate in the Assembly on equal terms with adults; that is, they have the same rights and responsibilities, having a voice and a vote.

Additionally, two of them are elected by the school community or volunteer themselves to manage and implement the Assembly’s agenda and note-taking. The recurring dynamic of these meetings is that someone makes a proposal or raises an issue and argues their reasons or motivations, and all voices are listened to and taken seriously, aiming at reaching an agreement or consent from the school community. In some cases, the adoption of a rule or decision is decided by voting, adopting the position of the majority; however, although the decision of the majority is assumed, what is actually discussed is a long-term consensus, as almost any rule can be revoked. From the perspective of school-culture building, the Assembly’s role needs to be understood in terms of scaffolding and guided participation and appropriation (Rogoff, 2003), where “more competent participants” in school community meetings share with others appropriate discursive tools, such as how to participate, speak, request the floor, and listen actively to others.

Similarly, some schools have adopted the sociocratic method with the aim of being able to hear all voices and going beyond majority rule, emphasising the common good, responsibility, and the consequences of decisions made. In a nutshell, sociocracy has four main principles: consent, circle process, open election, and double-link. This democratic governance method is implemented mostly in Dutch democratic schools. Yet it has extended to other parts of the globe, promoting an “inclusive and equitable way of decision-making, as collective decisions are made through the consent of everyone involved” (Osorio & Shred, 2021: 3). Within this approach, each circle makes sure that every voice is heard, while being represented in wider circles by community-elected representatives (Plesman, 1961).

The negotiated integrated curriculum and the 20% proposal

A negotiated integrated curriculum invites teachers and curriculum developers to involve students by asking about their concerns and using these topics to shape learning possibilities and teaching methods (Beane, 1997). This approach is closely related to the “curriculum of life” (Portelli & Vibert, 2002), focused on the students’ individual, social, cultural, and political contexts and concerns in education. According to O’Grady and colleagues (2014), the concept and practice of curriculum negotiation/integration in learning lies on several key assumptions:

- Schools need to become true learning organisations, not merely obligatory societal institutions that view students from a deficit perspective.

- A negotiated/integrated curriculum should be holistic and flexible, and encourage collaboration between teachers and students to tackle various themes and issues, including local and specific concerns related to the student, school, and community.

- Students can gain empowerment through genuine learning opportunities they choose, helping them answer the universal questions: Who am I? And what is my place in society?

- Teachers shall be respected as professionals knowledgeable about their subjects, students, and teaching skills.

On the other hand, the 20% Proposal, which emerged from the Democracy and Education conference held in Strasbourg in 2016, suggests that 20% of a school’s curriculum should be dedicated to learners-initiated learning activities based on their interests, concerns, and ideas. The main goal is to foster a more participatory, inclusive, and democratic learning environment by embedding democratic principles into the educational experience. For Hannam (2023), some of the key points of the proposal are:

- Student Participation: Allocate 20% of school time to activities that actively involve students in decision-making processes, including student councils, participatory budgeting, or class meetings where students can voice their opinions and help shape school policies and practices.

- Curriculum Content: Integrate democratic education into 20% of the curriculum by living core values such as civic education, human rights, social justice, and critical thinking.

- Teaching Methods: Implement pedagogical approaches that promote democratic values, including collaborative learning, project-based learning, and other methods that encourage student autonomy, critical inquiry, and respectful dialogue.

- School Culture: Foster a school environment that models democratic principles, creating a culture of respect, inclusion, and equity, where all members of the school community – students, teachers, and staff – are encouraged to participate and contribute.

- Community Involvement: Engage the broader community in the educational process, meaning that schools could partner with local organisations, parents, and community members to provide students with real-world democratic experiences and opportunities for civic engagement.

- Evaluation and Adaptation: Continuously evaluate the effectiveness of democratic education initiatives and adapt them as needed, involving gathering feedback from students and other stakeholders and using it to improve democratic practices within the school.

Some of the European experiences where learner-initiated projects have been accommodated (to flexible curricula, promoting autonomy and responsibility through independent research projects and personalised learning plans, and allowing them to focus on their interests and questions through self-directed learning, beyond the 20% of the timetable) are Summerhill School (UK), Escola da Ponte (Portugal), Ørestad Gymnasium (Denmark), Institut Beatenberg (Switzerland), Freie Schule Frankfurt (Germany), Evangelische Schule Berlin Zentrum (Germany), Big Picture Learning Schools (the Netherlands), and Pestalozzi School (Austria), among others.

In sum, the 20% proposal emphasises the importance of creating educational spaces where democratic values are not only taught but also practised. By dedicating a significant portion of the curriculum and school activities to learners’ initiatives, the proposal aims to prepare them to become active, informed, and responsible citizens.

A case study: the Participatory School in Tehran

Since 2005, rooted in the principles of humanistic education, the Participatory School in Tehran stands as a unique and transformative example of how a democratic, child-centred approach can foster active participation in learning, despite the broader socio-political challenges within the country. Despite encountering numerous challenges, this school initiative has persevered, establishing itself as the largest independent research effort in the field of children’s and adolescent education in Iran, operating autonomously from the Ministry of Education for nearly two decades.

Drawing on “Humanistic Education” (Yousefi & Yousefi 2014) the Participatory School places a particular emphasis on participation involving children, adolescents, families, and the broader community. Participation, in this context, refers to the active involvement of individuals in collective decision-making processes. It underscores the importance of collaboration and dialogue among students, teachers, families, educational planners, and the local community. Decisions within this framework are not imposed unilaterally but are instead the result of collective deliberation facilitated through active participation. (In the chapter on Utopias, there is more information about the Participation school in Tehran and the closely cooperating Peace school in Toronto).

The Travelling Educator project started among the middle class in the 13 Aban region. It was initiated to address the need for a more inclusive approach to education. The focus was not only on children, but also on engaging the entire community.

The 13 Aban plan aimed to create a participatory process where men, women, children, and families could recognise their abilities, broaden their perspectives, and utilise available resources. This approach helped individuals break free from limitations, experience personal growth, and unlock their talents. The project’s success continues because it empowered individuals to believe in themselves and actively participate in various areas. For example, women now hold weekly book reading sessions in public libraries, covering topics like psychology, education, family management, and parenting. Over time, their interests expanded to include poetry and literature.

As the 13 Aban project integrated education into people’s lives, it sparked new connections, revealed aspirations, and helped individuals identify skills to meet their needs. There was an emphasis on independence for participants, ensuring sustainability. In a region with many needs, empowering community groups and fostering their independence is vital, contributing to the project’s longevity of over two decades.

Supported by residents, various initiatives emerged, including the Local Kitchen Women’s Cultural Association, the Fabric Book Cooperative, and youth and fathers’ groups, sustained by a non-governmental organisation. The Local Kitchen promoted healthy eating patterns, providing nutritious snacks for children and encouraging plant-based foods. The Women’s Cultural Association supported children’s education through reading sessions, training courses, workshops, and kindergarten library support. After nearly 20 years, members saw themselves as responsible for children’s well-being.

One of the project’s most remarkable aspects was its continuity and growth. By adopting an open and inclusive approach to education, we learned that our work should extend beyond children alone. The project “Make a Wish for Our Land” aimed to prepare students for possible future migration (within or outside the country) by teaching them that life is organised differently in other communities than in their familiar environment. It thus facilitates later integration and participation. The project focused on fostering a sense of belonging and increasing awareness of cultural diversity within Iran. They aimed to explore the different ethnic groups in the country by organising trips to experience various cultures, foods, customs, and dialects across different regions. The belief was that understanding one’s environment would lead to greater responsibility as a citizen.

The follow-up project, Khorshid Mardom involved travelling across the country, reading books, and exploring local capabilities and regional characteristics. Participants documented their experiences through video and voice recordings and shared their findings about local foods and cultures on social media.

Rural and urban place-based community learning of young citizens

Aiming at changing the rural phenomenon of exodus to the slums of the cities, Sanjit Bunker Roy founded the Barefoot College in Tilonia (Rajasthan) in 1972, where one could become a “barefoot engineer,” a “barefoot doctor” or a “barefoot teacher,” meaning not to walk in shoes into the cities but to stay “barefoot” in the villages. Because of their success, ‘Barefoot College International’ now “was founded to address the needs of the most remote and marginalised communities around the world … by empowering rural women as agents of change, through a variety of localised education and skills development programmes” (Barefoot College, 2023: 14).

As these programmes address 14 of the 17 UN-SDGs, learners can integrate them in order to experience how collaboration works with underrepresented rural communities globally. Supporting learners “to sustainably address their most pressing challenges … including climate change, food insecurity, gender inequality, and lack of access to education and economic opportunity” (ibid.) as main issues, learners develop “tools (…) to redress the balance of power and shift it back to rural and indigenous people, (…) combating climate change, breaking gender barriers and protecting traditional ways of life” (). For instance, some training experiences included training women of the dalit caste to repair motors for water pumps or build sun-collecting lighters. Building knowledge and skills in the low technology sector is attractive to young learners, as well as being useful and relevant to their communities. Indigenous knowledge is no longer ignored but instead seen as valuable to build on ‘ecoversity’.

The Green schools that started in Bali (Indonesia) and the 18 United World Colleges (UWC) with learners from 120 countries who engage in environmental sustainability and nature conservation, creating links between rural places and cities around the world. An exemplary urban learning setting is the UWC in the divided Bosnian city of Mostar, where 8th-grade learners can choose to take their music lessons as band sessions in the Mostar Rock School (MoRS), consolidating it as an example of community change to more peaceful resonance impulsed by children and youth (Boban & Božić, 2023). Furthermore, the “Education Cities” initiative defines their work as “a campus for all”. In the words of Yasuaki Sakyo, Dean of Shibuya University (Tokyo), “when we looked down at the city from above, we imagined how exciting it would be if Shibuya became a university. We envisioned the entire city functioning as one university where everyone could enjoy campus life all their lives. It definitely fired our imaginations” (2012). Permaculture concepts like the ’eatable city’ or the ‘transitional towns’ like in Sydney invite all living place members to share responsibilities and powers for more partnerism to be experienced.

What can be done? – Taking action when revolution seems out of reach

As the previous section has shown, many forms of participation by children and young people in learning and community development require fundamental changes in schools and society. As these changes are so profound, they may feel beyond the reach of an individual teacher or educator, often leading to a sense of inertia. The question, therefore, arises: if systemic revolution is not on the horizon, what can be done in the here and now?

Build networks

Change often starts small, like a plant that needs a seed to grow. A starting point can be forming networks with allies who share similar goals, for example, students, parents, fellow teachers, school administrators, local government officials, or community members. Together, you can amplify your efforts and push for change more effectively. Networking with other initiatives that align with your vision will also provide opportunities to exchange ideas, strategies, and support, allowing your efforts to align in the same direction.

Familiarise yourself with the legal framework

While it may seem tedious at first, having a solid understanding of your country’s educational laws and policies can be a powerful tool. Knowledge of the legal framework allows you to navigate perceived limitations. For instance, when facing resistance from superiors or administrative bodies, you can ask for the legal basis of their objections and consult with legal experts if necessary. This approach ensures that your actions are grounded in law, providing you with the confidence to pursue innovative pedagogical practices.

Take calculated risks

In some social contexts, it might be more effective not to seek permission in advance but to act in accordance with the law and, when necessary, explain your actions retrospectively. If your initiatives are pedagogically sound and legally defensible, you can argue that your actions were justified within the framework of child-centred education. This approach empowers educators to take bold steps while staying within the boundaries of what is legally permissible. As mentioned above, ensure the safety of students and avoid online exposure of individuals.

Conclusion

The participation of children and youth in learning and community development can take many forms and be influenced by varying degrees of freedom, depending on the context. As this chapter has illustrated, participation is not a one-size-fits-all concept but a multifaceted process that adapts to specific cultural, political, and social environments. For instance, promoting participation under authoritarian regimes may be more challenging and even subversive than in democratic settings. Yet, in every context, participation has the power to disrupt established power dynamics, shift hierarchies, and redistribute influence in a way that prioritises collective decision-making (“power with”) over top-down control (“power over”).

Empowering children and youth requires confronting not only the structural limitations imposed by conventional educational systems but also the deep-rooted beliefs and societal attitudes that view children as incomplete, immature, or incapable of contributing meaningfully. So, in any case there is a potential not to damage the “inner power” of children and youth by adultism (Flasher, 1978) so that they can express themselves their “power for” what they are longing for. In many schools, teachers, parents, and policymakers still uphold hierarchical power dynamics, assuming that asymmetry between adults and children provides protection and continuity. However, today’s complex world demands an educational shift towards self-awareness, co-constructed learning, and shared leadership. By rethinking how we structure learning environments and redefining the roles of children and adults, we create spaces where young people can assert their agency and actively shape their futures.

As this chapter has shown, participation is both a deeply personal and collective process. It begins with the opportunity for self-expression, recognition of one’s abilities, and the possibility to be heard and understood. Participation may be part of a more significant, radical transformation aimed at overturning the educational status quo – such as revising curricula, rethinking teacher training, or involving young people in political decision-making at higher levels. It may manifest in small yet meaningful acts of everyday engagement, such as giving children more autonomy in the classroom, allowing them to pursue projects of their own interest, or involving them in community decisions. These acts may seem minor, but they chip away at entrenched beliefs and gradually lay the foundation for more significant systemic change.

The examples throughout this chapter underscore the importance of networking and collaboration. Teachers, parents, local leaders, and community members can all serve as facilitators of change, providing the fertile ground where participation can take root and grow. However, the process of participation is reciprocal: it not only “takes a village to raise a child”, but also “takes children to help develop the village”. Their contributions – cultural, social, political, and intellectual – bring new perspectives that enrich the entire community.

Ultimately, to enable participation at all levels, it is necessary to engage in the revolutionary act of unlearning. This means letting go of tradition-oriented narratives that limit the potential of children and youth and embracing new, creative approaches to education and community building. By reimagining the role of young people as active participants in their own learning and community development, we take an essential step towards creating more inclusive, democratic, and participatory societies.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Power dynamics in education: Reflecting on the examples of democratic schools and participatory learning models, how do traditional power dynamics in schools (teacher-student relationships) inhibit meaningful participation? What steps can be taken to shift these dynamics toward more equitable power-sharing?

- Cultural and contextual considerations: How does the cultural and political context of a society influence the way participation of children and youth is approached? For example, how might efforts to promote participation in a democratic country differ from those in a more authoritarian regime?

- Small and large-scale participation: The chapter highlights both small acts of everyday participation and significant, systemic reforms. In your view, what could be a small step and a large-scale horizon in your situation?

- Unlearning hierarchical structures: The concept of “unlearning” traditional hierarchical structures was discussed in the chapter. What are some of the challenges educators and communities might face in “unlearning” these practices? How can they begin the process?

- Legal frameworks and participation: The chapter emphasises the importance of familiarising educators with legal frameworks to navigate barriers to participation. How can knowledge of the law empower teachers, students, and communities to push for greater participation in schools?

- Participation beyond school walls: How can participation in learning extend beyond the classroom to foster community development? Can you think of any local or global examples where youth have successfully contributed to social, environmental, or political change in their communities?

Literature

- See the European Democratic Education Community for further examples of the implementation of democratic principles within learning environments www.eudec.org ↵