Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

An Introduction to Person Centred Planning – and Its Potential for Schools

Andreas Hinz; Petra Elftorp; Sandra Fietkau; and Yuzhen Xu

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case – He made a difference

“Tow was an eight-year-old boy in China, diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and emotional behaviour disorders. He was very aggressive and often came into conflict with his classmates, even hitting other people at times. Students and parents were angry and complained to Tow’s teacher.

Tow’s parents were divorced, and he lived with his father and his grandparents. The father was unemployed, and his parenting style involved ‘fist and violence.’

The grandmother took care of the whole family and was under a lot of pressure. She felt that her neighbours were unfriendly because of their unhappy family. She was also emotional and complained endlessly.

The school felt challenged in terms of Tow’s education, while there was also tension in the community where Tow and his family lived. The school and the community sat together and talked about how to improve Tow’s education and community life. They developed a plan with the boy and his family, by holding discussions two or three times a month. Multiple departments in the school and beyond worked together. For example, social workers and a psychologist visited the family; community workers communicated with the residents to develop their understanding and acceptance of Tow and his family. Medical doctors were also involved when needed. School teachers encouraged empathy and care from classmates and parents. They helped the boy to develop his interest in music and carried out positive behavioural interventions.

Thanks to the support from both inside and outside the school, over time, Tow’s life greatly improved. He started to really enjoy coming to school and got along much better with his classmates.

In the neighbourhood, someone said, “Oh, his mother is not around, I would like to be his ‘mother,’ or to give him the love of a mother.” Tow’s family also made some changes. His father became more positive and tried to find a job; his grandmother felt the passion and friendliness of the people in the community, and established good relationships in her neighbourhood. As Tow grew, so did the teachers. Learning by doing, teachers constantly study and experiment with intervention methods, and they were inspired by Tow’s progress.”

Yuzhen Xu, China

Example 1 – A boy always said: I want to become a medical doctor!

“My name is Ines, and I’m a very lucky person because I had the chance to learn about Person Centred Planning and support circles, and I facilitated a lot of these circles during the last 30 years. I really must warn everybody because it’s something you can be longing for, if you know how to do it, because it’s a very essential thing. In a way, it’s a key thing for feeling humanism in the world – and it is at the heart of inclusion. It’s not a method I was operating, but when I heard about it, I was sure that I wanted to do things like this. To give you just one example:

There was a young man who, as a little child, already started to think about his future. He thought about ‘What would I like to work as? I want to become a doctor, a medical doctor!’ This is what he said. When he explained this to his mother it was a little bit special because he had Down’s Syndrome, he had the 21st chromosome three times. However, in some cases, our societies seem to know what is possible and what is not! So, the mother felt all the time: ‘Oh, how can I explain to him that this will never happen, and no university will accept him?’ This was a big thing in the family.

It was a wonderful thing when he was a youngster that his mother told others: ‘Oh, he always tells me he will be a medical doctor in the hospital. How shall I stop him from this stupid idea?’ They built a circle around him. They had a meeting, and they did some Person Centred Planning. So, they gathered all their friends around and the people who facilitated these processes, they all knew that it’s a gift if somebody has a certain dream. Very often you have to work to see what the dream is and here this young man was always talking about his dream.

The group had the challenge of finding out what the quality of this dream was and what lay behind all this. What does it mean for anybody to be a doctor, and especially for him, if he can express it? Maybe it means to be an important person, a helpful person. Maybe it means how to be dressed and to receive respect because of what he is doing and so on. So, the wonderful thing about this circle was that they were thinking in that way: Okay, we have to find a position for him, and create it, if it’s not already existing, where he can have all the things he wants without going to university and studying medicine. And luckily, one of the friends sitting there, she knew somebody who knew somebody … and sometimes you need these types of relationships.

So, to make a long story short: The outcome of the whole thing was that he got a job in a clinic for people who lay in a coma. And yes, his role was wearing a white skirt, he was going into the rooms, filling with the disinfectant for everyone’s hands. He ensured that everything was where it needed to be for when the beds were dressed. He was also allowed to sit at the beds of people and touch their hands, to talk to the people, to be soft with them, and to tell them some stories about what is going on outside. I could cry from being so moved when I relay this story.

Then he genuinely didn’t miss any medical studies, and he never asked to go to university. He was happy being a relevant person in this context, and his dreams were fulfilled. Maybe one day he will be unhappy. Or maybe one day somebody will tell him that this clinic doesn’t work anymore and so on. Then he will know that it’s a wise thing to gather good people around you and talk about what you’re longing for and then find relationships to help solve these problems. Find steps to bring it into the world if it doesn’t already exist. Then the community will win, will gain a lot, and will change. I’m sure this is a win-win-win-situation. It certainly has been in this clinic. He will always be a winner if he does it this way. That’s my story. This was one example with a person labelled as having a disability.”

Ines Boban, long-time activist for facilitation of Person Centred Planning, Germany/Croatia

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find answers to the following questions:

- What are the basics of Person Centred Planning?

- What makes Person Centred Planning specific in relation to other forms of planning?

- What are the main principles of Person Centred Planning?

- What is the difference between Person Centred Thinking and Person Centred Planning?

- What are the areas, potentials, and challenges of Person Centred Planning?

- What theories could help explain why Person Centred Planning works?

Introduction to Topic

Person Centred Planning happens when a group of people come together, dream and gather ideas during one, or several, meetings. Mostly the planning is done with and for one person, which we refer to as the ‘main person.’ It can also be done for a group, a project, or systems – like schools. During the planning process, a collective vision is created on what a good life in society could look like and how it can be achieved together. The focus is on the strengths of the person, group or system and relies on a form of co-construction.

Person Centred Planning is interesting for several reasons, not least for teachers:

Firstly, it helps to start dialogues. Of course, teachers have lots of dialogues, but often about academic topics, or about children (with colleagues and parents) and perhaps not so much with children about their dreams and thoughts about the future, especially if they define themselves mainly as a teaching person and less as a learning supporter.

Secondly, Person Centred Planning promotes thinking outside the box as there is an emphasis on dreaming and developing new ideas in a safe space without judgement. As Person Centred Planning is independent from institutions, the place, or the institution should not limit reflections and ideas.

Thirdly, it helps to see the whole person and their future, not just past experiences or individual achievements. Person Centred Planning is – as the name suggests – centred on the person, not on some aspects relevant to school.

Fourthly, it helps to reflect on your own role as a teacher and your ideas and dreams for your future.

Finally, it may inspire you to look for opportunities to start Person Centred Planning processes in schools – for students and perhaps even for the school itself, in a person centred context.

Key aspects

Basics of Person Centred Planning

In order to present the underpinning conditions for Person Centred Planning, we draw on Beth Mount’s work as she identifies four central aspects. We refer to these as the four cornerstones of Person Centred Planning (Mount, 2014), as can be seen in Fig.1.

Figure 1: Four cornerstones of Person Centred Planning

The first of the cornerstones is about finding the gift in the person. This is based on the idea that everyone is unique and has their own set of key interests and abilities. It is important to note that this is not about finding a hidden talent or ‘superpower’ within the person. The ‘gift’ does not have to be extraordinary; it can be a wish to help others, or to care for animals, for example. It is about finding out what ‘makes someone tick,’ or what makes someone smile in the morning. While some are very clear about their own strengths, interests, and dreams, many people need help from others to figure out what that is. In practice, there are many ways of exploring this with the main person. For example, you may ask a question such as ‘What would an ideal day look like for you?’ Or: ‘What are the things you think about when you feel really good?’ These types of questions are utilised to find out what the gift in the person is. In the school setting, perhaps you as a teacher could pay particular attention to the subjects or topics that a student is interested in, to explore that further.

The second cornerstone, building relationships of commitment, on the one hand focuses on people coming together for the Person Centred Planning; thinking together; coming up with ways of supporting each other. During the planning meeting, relationships are deepened, or sometimes even just started. These relationships can be based on mutual interest, for example, during a planning meeting two people find out they are both big fans of the same soccer club and decide to watch games together at the weekends.

Also, these relationships can be based on mutual care and support, the interest in each other’s well-being. For example, one person at the planning meeting agrees to accompany the main person to their doctor’s appointments, making sure that the voice of the person is heard, and the person understands what the doctor says and wants.

On the other hand, the relationship aspect also focuses on broadening the relationship circle. Expanding the circle is a way of developing social networks of people and looking for people that are not yet part of the circle but could be helpful for what the circle is working on or could also benefit from being part of the circle. In a school setting, it could be something as simple as running a board games club at lunch time, to help broaden the social circle of a student – creating opportunities for students who share a similar interest to make new friends.

The third of the cornerstones is asking for more from organisations. This is about acknowledging that when there is a dilemma pr problem, it is not always an individual that should have full ownership of that problem. Often, issues can be structural and shared with other people in the same, or similar, settings. When structures are in place which lead to several people, or groups, experiencing difficulties, organisations should be asked how they can change or develop to support individuals, or groups, better. An example from a school setting is, there could be several students who have an issue with the school uniform policy, maybe because of a gendered dress code which makes them feel very uncomfortable. Rather than coming up with a workaround for one student at a time, we could be asking for more from the organisation, in this case the school! This may involve empowering the students to come together to influence and have a say in how we can make the school uniform policy more inclusive.

In other scenarios, it may also be a neighbourhood that could be ‘asked to do more,’ like in the case of Tow where the neighbours were instrumental to the solution of a difficult situation. Or it could be a medical clinic, as in the case of the boy with Down’s Syndrome, where a bespoke solution led to a meaningful job where he could realise his dream.

The fourth cornerstone, Beth Mount refers to community: finding assets and openings in communities, looking for places where people can thrive. Or to paraphrase: ‘digging into the social goldmines of community.’ With this fourth aspect, Beth Mount emphasises the need and potential for connection. Within communities, either local or distant, there is almost infinite potential, if we keep looking for it. Find people, explore places, look for groups, events and organisations to find these openings that create opportunities for people to lead a good life. Also, this cornerstone emphasises the need to look for a diverse group of people participating in Person Centred Planning. The more richness and variety, the bigger the connections into various places and communities will be so the main person, and the circle, can benefit. In case of a school, the places in community can be clubs or organisations that would like to co-operate, for example, a sports club that offers its’ training field to interested students, or a local bakery that offers their business to a group of students for a limited time in order to learn about production and sales from the actual process of producing and selling baked goods.

Different approaches to planning

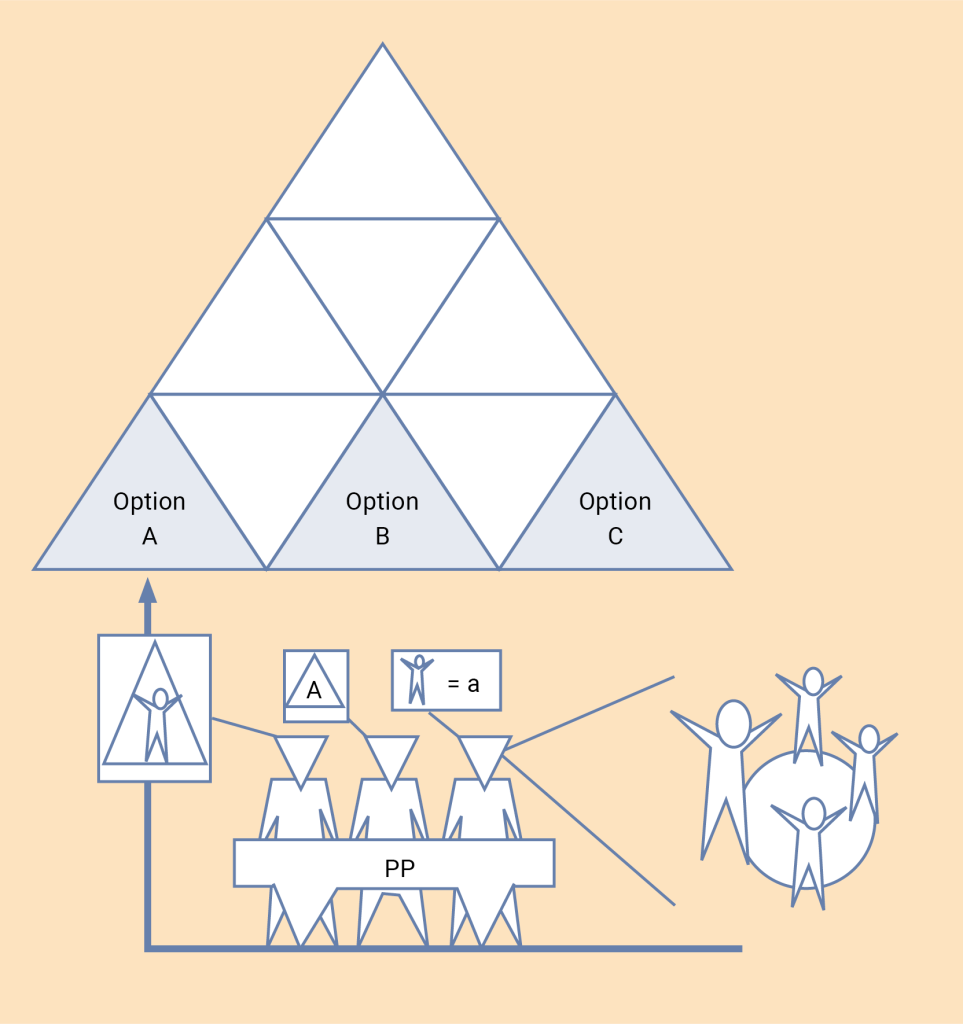

In order to highlight what the essence of Person Centred Planning we are drawing comparisons with more traditional approaches to planning. In general, there are many different forms of planning. John O’Brien, one of the developing pioneers of Person Centred Planning, illustrated this very well in his publication from the 1990’s, with the two images (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Individual Program Planning

In Figure 2 the idea of a more traditional approach of individual program planning is illustrated. There is a team of experts with specific knowledge and context sitting together, displayed here with triangle heads. They are triangles because this fits into the existing system of institutions and pre-existing options. Now, the task for the experts is to find out which existing option fits which person. These options are usually based on medical categories and especially on medical or psychological deficits. Here, quality is defined as being sure to decide on the best match between the person and the option. The power is, of course, in the hands of the professional experts, and the person is just an object of their decisions. This demonstrates a hierarchy between the decision-makers and decision-recipients.

Figure 3: Person Centred Planning

![A diagram showing a group of people seated around a circular table. They are discussing and planning a “positive future” for a central figure, who is depicted within a box labeled “A positive future for [the person].” Speech or thought bubbles with exclamation and question marks suggest collaborative brainstorming. An arrow from this planning circle points toward two concepts on the right: “Community capacity” (drawn as a circular net) and “Service capacity” (drawn as a triangle). The overall image represents a person-centered planning process, where power and decision-making are shared among the person, family, friends, and possibly a professional expert, rather than dictated by a hierarchical system.](https://book.all-means-all.education/app/uploads/sites/2/2024/07/AMA019-An-Introduction-to-Person-Centred-Planning-–-and-Its-Potential-for-Schools_4-1024x492.png)

Person Centred Planning (Figure 3) is based on quite a different way of thinking and making decisions. In Figure 3 there is a group of people sitting in a circle around a table, having round (or maybe egg shaped) heads. Sometimes there is also a professional expert involved, there is a big question mark in the thought bubble, to display a different way of thinking. This group consists of the person, maybe family members, maybe friends, maybe supporters, all of these diverse group members are experts in different ways. They create, reflect and plan a desirable future with, and for, the main person. This brings new challenges for institutions, especially for services, and for the community. However, it also offers a chance to grow inclusively. In this approach to planning, the main person is not an object but a subject and part of the planning process. In this way of planning, quality means something different than before: everyone has the chance to contribute and to participate in the planning process. This decentralises the power of the original decision-makers involved in the hierarchy. The power is in the whole circle, shared between everyone, not only among professional experts. These are two different examples of the planning processes that will display different results and have different consequence with a disparity in quality and power dynamics. This fits into four cornerstones:

- You need to know about the gifts of a person to create a desirable future.

- You build relationships within the support circle during this process.

- You create new opportunities and challenge existing universities to be more inclusive and

- You connect with communities.

Practices – Ways of Person Centred Planning

Person Centred Planning can be practised in different ways. However, there are some shared aspects which are outlined below. The two main ways to work person centred are Person Centred Thinking and Reflecting(sometimes called ‘small ways’ with less time and fewer people) and Person Centred Planning (sometimes called ‘big ways’ with a lot more time and more people involved).

Shared aspects

There are some aspects which feature across the whole spectrum of person centred practices, namely:

- Thinking together. The goal is to bring together all types of ideas from different people with different perspectives and backgrounds – maybe also ideas which seem a bit crazy at first!

- Everyone’s an expert. People come together, sit together, have time together, and collect ideas. There is no professional expert who tells anyone what to do and how to do it – it is an open process where everyone is an ‘expert’ and there is no right or wrong. This requires an accepting and non-judgemental mindset.

- Voluntary. Person Centred Planning should be initiated freely by the main person – maybe with the support of others. There are no time limits or demands for when, where or what someone should do. It is always a personal decision if a person wants to be involved, when, with whom and where to do it. The main person also sets the agenda for the Person Centred Planning. Very often, it is about the future, how to live a good life, what to work as, with, where and with whom to live – all “great questions,” which do not have simple and quick answers (Snow, 2015: 9).

- Everyone in the circle matters. Another aspect is that the perspective of the main person is crucial, but also the perspectives of the whole circle are important – as they are all ‘thinking with’ the main person.

- Visualisation. Almost all Person Centred Planning meeting use visual recording on posters. This is important for two reasons: It makes sense that the whole group can see and feed into the visualisation of what has been said – and the poster will be given to the main person afterwards if they want it. This is a way of making dreams visible. Also, visualisation through a poster slows down the process, so members of the circle have more time to think, to share ideas or develop fantasies without limitations. Every idea is valued, there is no competition surrounding ideas, for example, ‘my idea is better than yours.’ All ideas are welcomed and will have their place on the poster.

These are the main and shared aspects of Person Centred Planning.

Methods of Person Centred Thinking and Reflecting

The methods of Person Centred Thinking and Reflecting are sometimes referred to as ‘the smaller ones,’ as you can use them everywhere – in your school, with your team, in your classroom, at your workplace or elsewhere, for example, in your club or in your choir or wherever you are together with people. They can be helpful from a reflection viewpoint. There are hundreds of different examples, and you can find them on the homepage of Helen Sanderson, a councillor of the English government and many worldwide organisations (https://www.helensandersonassociates.com/person-centered-thinking-tools/).

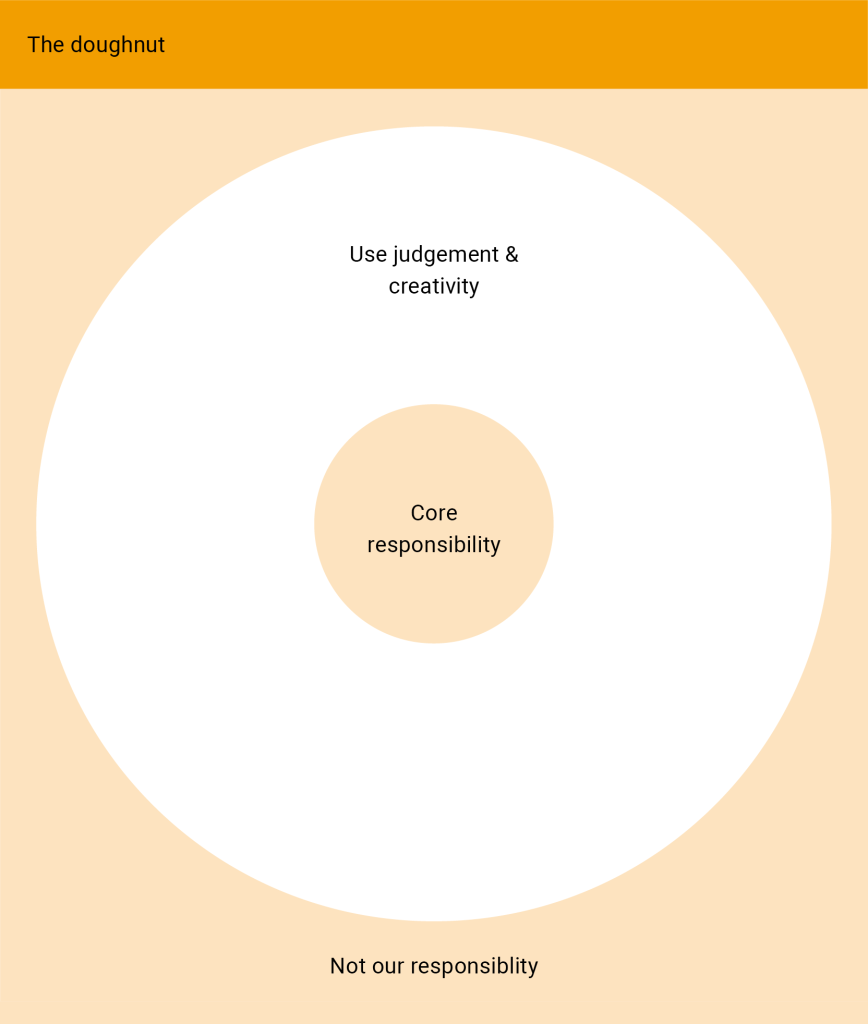

Figure 4: The doughnut

One example is called the doughnut – useful for reflections on responsibilities. You see three concentric circles. The inner one is about the core of someone’s responsibilities – there you can write about your duties, things you have to do. The second one is about the ‘nice to do’ area. If you have enough time and energy, it is nice to do certain things. The third one is about the ‘not my responsibility’ area. It’s not your task to do that. Sometimes it can be helpful to make that clear for different people within a team who may be in the same situation. Who’s responsible for that? Of course, you can talk about it without the poster, but it can be helpful to have this visualisation, to create a picture together. This can make it easier and more structured.

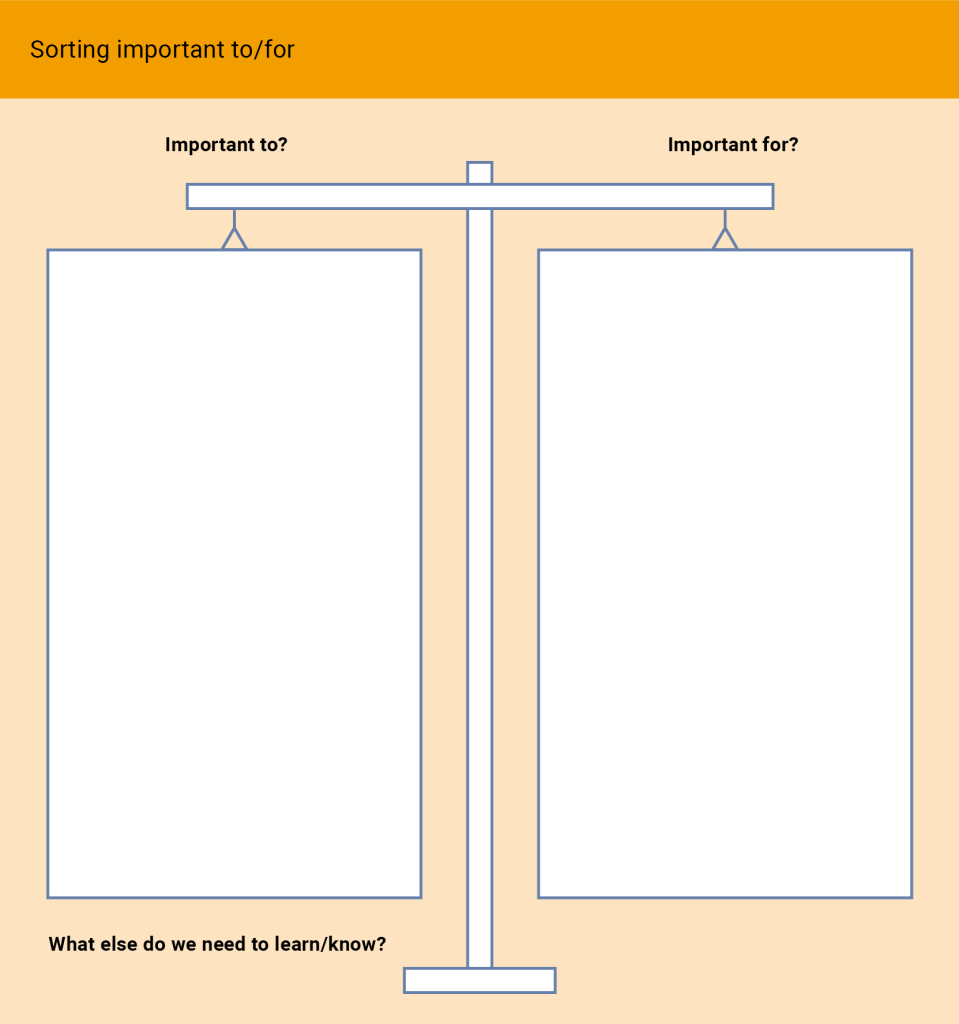

Figure 5: Sorting Important to/for

Another example is called ‘important to/important for.’ Often people do not differentiate between what a person thinks is important to them and what others think is important for the person. In institutionalised situations this could be quite contradictory. The poster helps to find out who means what and it helps to find items that overlap and items that dissent.

A common way to illustrate this is related to food – whereas a lot of people enjoy eating sweets or snacks – therefore it is important to them. A healthy diet including vegetables and fruits is considered important for the human body – therefore it is important for them. After adding important aspects on either side, a compromised solution should be developed together.

A third example helps to reflect on and increase inclusive processes in a group situation. This illustrates moving from just being present or in a situation, to being an active contributor in a situation (Figure 6).

Figure 6: From presence to contribution

If there is a situation where someone is marginalised or isolated, you can sit together in your team, maybe with the parents, and you can think together about how to move from simple presence to more actively contributing to situations. There are several stages in between and different opportunities to participate, connect, and contribute.

These are just three examples of the ‘small’ ways of Person Centred Thinking and Reflecting. As mentioned before, there are many more available in publications and on the internet.

Ways of Person Centred Planning

In contrast to quicker, sometimes less complex ways of Person Centred Thinking and Reflecting, Person Centred Planning starts with a few preparatory questions and tasks:

- Identifying a ‘great question’ / issue. The main person is asked to phrase (or develop) the main question or issue that they want to work on with the support circle in the Person Centred Planning process. Sometimes, the facilitator will be involved in this first step. Person Centred Planning is a good way to jointly think about ‘great questions.’ As Snow (2015: 9) states

“Great questions are the ones that refuse to be answered. They lead to deeper listening and better connection.”

An example might be, that the question will not be about ‘What do I like for dinner tomorrow?’, but maybe about ‘Who will I be when I grow up?’ or ‘Where shall I work?’ It is a big question that needs several people to think and plan together.

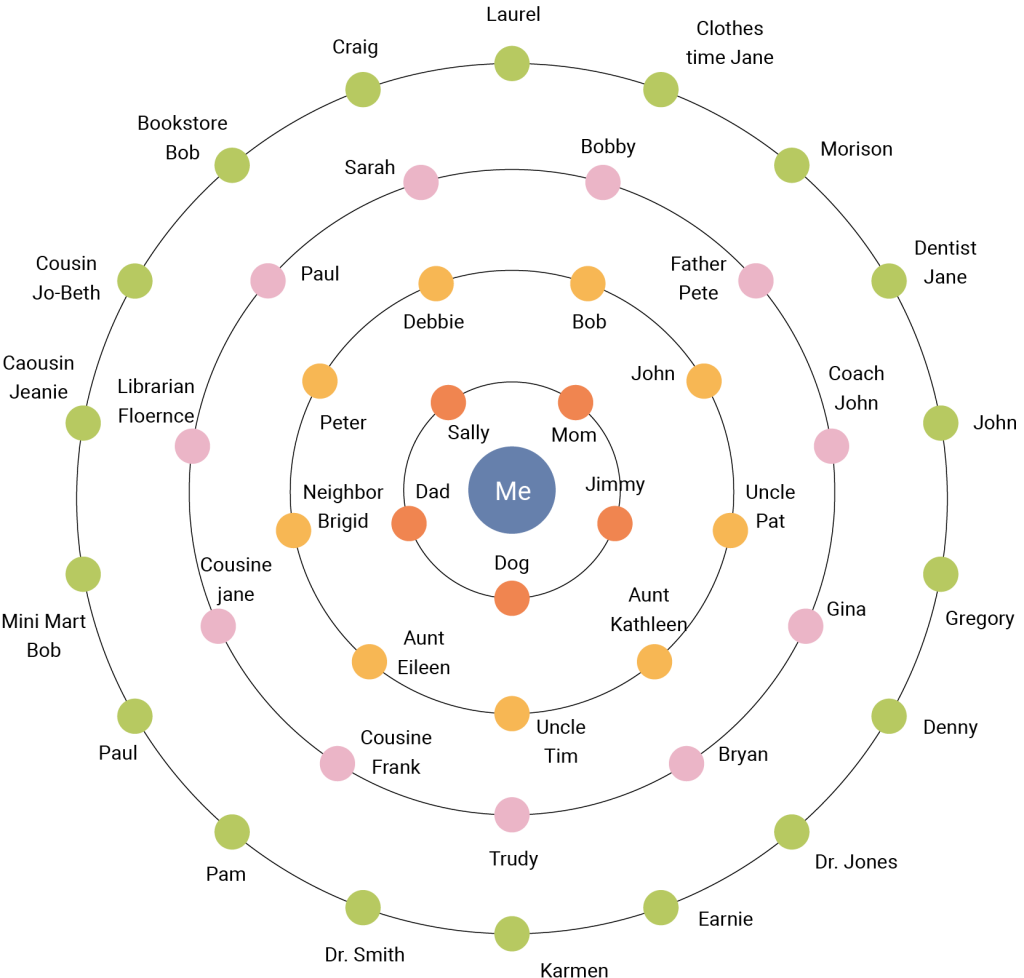

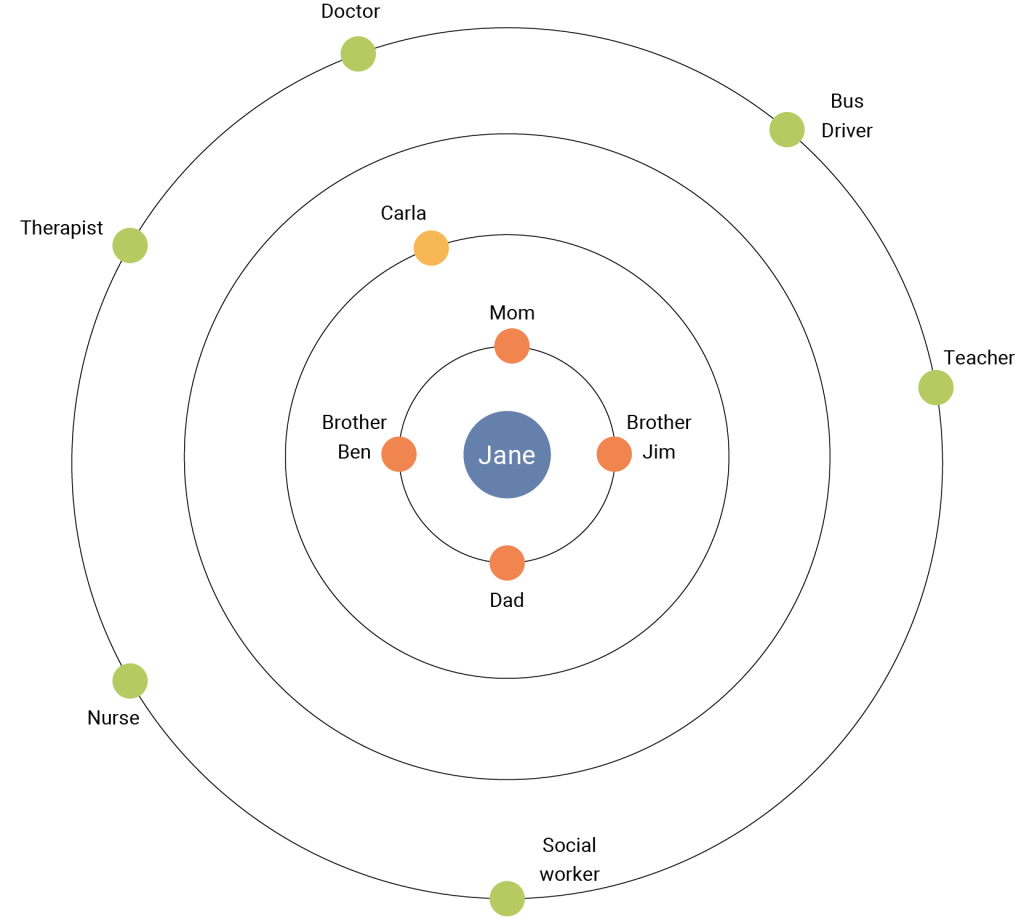

- Relationship map. Another important question to start with is ‘Who is in my life?’ and ‘Whom do I know?’ There are various templates for the relationship map with multiple concentric circles (see Figure7a). This can help the person to reflect on how important different people are in their lives. However, it can also be done on a blank piece of paper, by naming and writing down all the people that the person can think of.

Figure 7a: Circle of Friends of a High School Student

Figure 7b: Circle of Friends of a person with ‘at risk’-Label

As shown in the examples above (Figures 7a & 7b), there can be lots or just a few people in a person’s life, depending on their current situation, their past or other reasons. It is important to try and gather all the names and then possibly also think about how to increase the circle, for example by ‘borrowing’from people who are in the person’s life and who do have a full relationship map.

As a second step, it is important to think about ‘Whom do I want to participate in the planning?’ and‘Who will be invited?’ This decision will also be influenced by the ‘great question’ or issue which has been identified.

- Setup. The next preparatory task is to think about a good place for the meeting. It should be a setting that suits the main person and their needs. For example, it can be their favourite coffee shop that has a quiet second room, a room in a community centre, or also somebody’s living room if that is what the person wants. In terms of setup, some thought should also be given to food, decoration, a centre piece in the middle of the circle, music or other things that contribute to the wellbeing of the people present and to ensure that the planning meeting is a pleasant experience.

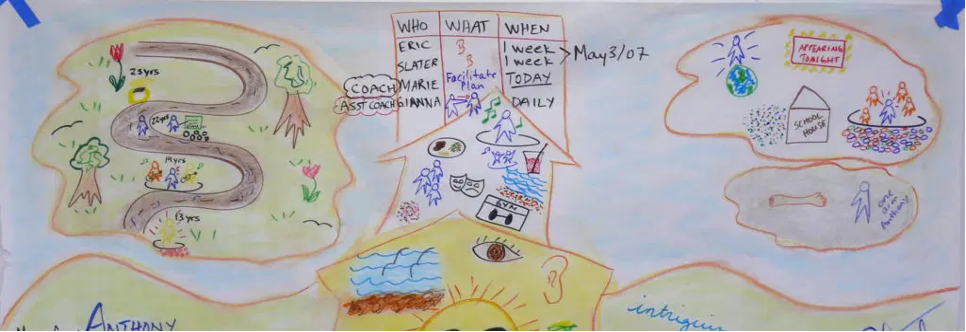

- Facilitation. Person Centred Planning is typically required to have two facilitators. One facilitator makes sure that everybody’s voice is heard and that all people present in the meeting have a chance to contribute. Usually that is also the person who helps to prepare the planning meeting with the main person. The second facilitator is the graphic recorder. Their task is to ensure that everything being said and planned is depicted on the poster. Visualising the things that are happening during a planning meeting with symbols, pictures, and colours is useful to express and depict feelings or images of dreams. It also helps to spark creativity and imagination and leads to a different atmosphere than if things are ‘just written down’ on a flipchart.

There are different ways of Person Centred Planning. The two most well known are probably MAPS – like a treasure map – and PATH – like a path to the dream (O’Brien, Pearpoint & Kahn, 2012).

MAPS contains a set of questions to learn more about a person, their interests, strengths, gifts, dreams and needs. All questions are thought of together in the group to make sure that everybody can contribute their answers.

Figure 8: Example of a MAPS

PATH is used when there is a need to think about how to achieve big dreams and how to reach certain goals. It invites the planning group to plan, step by step, to think of what else, or who else, is needed to make progress and what the group needs to work towards the dream.

Figure 9: Example of a PATH

Sometimes, neither MAPS or PATH are used in a meeting. Other times, in longer meetings for example, they may start with MAPS and then move on to a PATH planning afterwards (Hinz & Kruschel, 2013).

A Person Centred Planning meeting will very often leave lasting memories for everybody involved. Many people say afterwards that, for them, it was “an honour to be invited.” When recalling some of the meetings that we taken part in, there are two aspects that will never be forgotten:

Gathering different ideas and dreams: During the Person Centred Planning process, all people present are invited to share their dreams and visions for the main person. In Sandra’s example, which is mentioned below, it was a wonderful surprise both for the main person and the group to look at all the ideas gathered and to realise how diverse and inspiring they were. This variety can only be collected when taking time and planning with a group and not when thinking on your own. Margaret Wheatley says:

“We need time to think about what we might do and where we might start to change things. We need time to develop clarity and courage. If we want our world to be different, our first act needs to be reclaiming time to think. Nothing will change for the better until we do that” (Wheatly 2009:103).

Encouraging the main person by sharing their strengths and talents is done in MAPS. One of the first questions all the participants are asked is to think of the main person’s strengths, talents or gifts. During one meeting, everybody was given some index cards to write down all the strengths they saw in the person. After they had written on the cards, they took turns to present their cards to the main person. It became visible, gradually, card by card, how much this meant to the person because with every single card the person sat more upright, became more present and smiled a bit more.

Challenges and misperceptions of Person Centred Planning

As with most things in life, Person Centred Planning comes with some challenges and there are some common misperceptions which this section addresses.

There are many Person Centred Planning projects, practices and publications connected to disability. This makes sense because for people labelled this way, it is much more difficult to leave traditional ways of institutionalisation and to step outside of their boundaries to create their own good life. Some people may say that Person Centred Planning is for people with a disability.

However, this would be a problematic limitation to the possibilities of Person Centred Planning. Jack Pearpoint, one of the pioneers in Person Centred Planning, “never thought that this work was about disability” (2011: 76). Person Centred Planning started in the field of marginalised people and their emancipation. It can be used for every person who is in a situation of not knowing how to move on. This method will work for any person needing support in developing new perspectives for their future and some help to find answers to some of life’s “great questions.”

Some people believe that Person Centred Planning aims to increase self-determination. Of course, it is an empowering process for the main person, but that is not the main aim. It is much more about being and feeling included in the community by using a systemic approach. There are always people around the main person involved. That is why it is not a peer-counselling approach but an approach with a support circle as diverse as possible. Although people of the same age and with similar experiences sometimes are extremely important for free association and for creating a positive dynamic.

“All means all” also relates to age. There is a wide spectrum of people who can benefit from Person Centred Planning – you could say from 5 to 85, as the following two examples demonstrate:

Example 2 – Where to go to school and be welcomed?

In this example, the main person is the five-year-old girl speaking seven words. Then, secondly, in a systemic understanding of person centredness, the parents, who were feeling powerless, can also be considered main persons.

Example 3 – How to have a good time until the end of life?

“My mother had decided to move into a senior’s home in Germany for her last years. She didn’t know what would happen there, she was non-verbal after a stroke. Institutionalisation was evident, starting with ignoring her personal wishes, for example, giving her coffee (which she hated) instead of tea (which she loved), switching on the radio to pop music (which she hated) instead of classical music (which she loved as a former piano teacher) etc… I felt the need for Person Centred Planning for her, or should I say also for me, as her legal guardian. We invited people from the family, the neighbourhood, friends, but no one from the institution, as we had no trust in them. We did something very strange: My mother wasn’t there because she didn’t feel well, so, we did it without her, which is usually not correct. If you work in a person centred way the main person should be there. However, that was our situation. Finally, right after the meeting, we read the ideas we had agreed upon to my mother and she squeezed my hand a little with her hand, which we interpreted as her consent.”

Andreas Hinz, Germany

This example (Hinz, 2015) shows that in addition to the systemic approach, you also have to be flexible, to adapt to the situation, the context and the culture you are in. On the other hand, there are some principles which are really important, for example, not to plan without the main person. These must be followed and respected in order for Person Centred Planning to remain as open and powerful as it has been since its creation. That is why we introduced the four cornerstones at the beginning of this chapter.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, virtual meetings and gatherings have become more common. This might also be an option for Person Centred Planning, at least according to some facilitators and people who don’t have much time or don’t want to travel. Of course, online gatherings might be feasible if the other option is to not meet at all. It may also work for a follow-up meeting. For the main planning session though, when meeting for the first time and for establishing the support circle, we strongly encourage in-person meetings and believe in the power of people physically gathering in a room, just like Jana Zehle emphasises:

“At the same time, however, I would also like to emphasise that building and maintaining relationships requires a physical, concrete encounter that is created and experienced in dialogue in the sphere of interpersonal relationships and not in the digital realm of possibility or possibly with a digitally controlled counterpart” (Zehle, 2024: 17).

There are also other challenges to Person Centred Planning, which we look at briefly here:

One challenge is connected to the cultural context. In some societies, dreaming is not encouraged (during the day), and it may seem unthinkable to dream together with others – as could be seen in the example story of the boy who wanted to be a medical doctor. In some societies, talking about challenges openly may be seen as a weakness. For example, in Germany, there are often discussions before a Person Centred Planning meeting, reviewing if a person or a family really needs this and if they should rather solve ‘their problems’ themselves. Even the idea of who could be called ‘a friend’ differs from society to society. In some places, Person Centred Planning could be seen as something ‘exotic.’ In other societies, maybe in some parts of Africa, where the culture of Ubuntu is still alive, it may be more acceptable (Asante, 1997).

There are also many challenges for the people who facilitate Person Centred Planning:

- Their role is to make sure that each and every voice is heard and their ideas influence the process and the poster, for example when using MAPS or PATH (see above). On the other hand, no one should be put under pressure to say something and to contribute.

- Sometimes, complicated dynamics could arise. For example, the mother, the primary teacher, and the secondary teacher may compete to see who knows best how to protect and support the main person. Or it could be a family with divorced parents where the father is living apart from the rest of the family. If they meet during the planning, there could be tendencies of devaluing him by sarcastically saying: ‘Wow, he has an idea – wonderful!’ Or it could be difficult to find a gift in the person, especially if the perception of the circle members is that everything is difficult; everything is terrible; there are no people around; and that there is nothing they can do.

In this instance the facilitator’s job is to reframe the situation as even the most terrible situation could have a potential for positive change. Therefore, facilitation is not easy, but it has tremendous potential. As Ines Boban (2007) once said, about the role of the facilitator: “You have to dance with the group!”

Examples 4 – Deciding on job opportunities

“About 10 years ago I was about to finish my academic education and began to wonder where my ‘job path’ would take me. I started having conversations with a lot of people, which resulted in many interesting, highly diverse ideas and recommendations. Looking at these possible next steps, I felt unable to find an answer to this question by myself. As I am also a facilitator for Person Centred Planning, the next thought was obvious: I will have Person Centred Planning for myself!

After finding a facilitator friend who agreed to host the meeting, I started with a relationship map and was amazed by the number of people I knew. The page was full of names. Then there was a major task of choosing who to invite to the planning meeting. In the end, there was a group of about 20 people coming together and thinking about my job path. It was great to learn all about what people thought I was good at and what their ideas were about what I could do next. Some of the things I had never thought of myself, so they were quite surprising (like using my interest in books and opening a bookstore). At the end, with the support of the group, I was able to decide, and we jointly developed a ‘10-year path’ and dreamed of all the major steps that would happen in the next 10 years. Looking back, I still feel very empowered by the Person Centred Planning and even though I didn’t look at the path too often, I lately realised that almost all of the things written there I accomplished. Maybe it is time for another Person Centred Planning?!? ”

Sandra Fietkau, Protestant University of Applied Sciences Ludwigsburg, Germany

Person Centred Planning in projects and systems

Until now within this chapter we mainly focused on person centred planning and their families as a systemic background. Person Centred Planning can be practised on different levels (Kruschel & Hinz, 2015). It is also suitable for entire systems, for example, a whole city on the way to inclusion. An example of this is the city of Wiener Neudorf in Austria who started a project to become more inclusive (Braunsteiner, 2016). First, they connected kindergartens with the primary school and the communal parliament, and children began to have a monthly hearing in parliament. The municipal government unanimously decided to commit itself to the values of inclusion. Some years later, they expanded this to the whole city, with areas that were meeting places for people, a better cycling system, a welcome package for newly arrived migrants and lots more. Again, some years later, the steering group evaluated the development. Every planning stage was done using MAPS and PATH; the initial, the extended, and the reviewing processes. Many different people, from children to the elderly, were involved, and every time all of them dreamt of the most inclusive city they could imagine. Then they implemented lots of steps in the plan, many of them much earlier than planned.

Person Centred Planning can be a great support for projects, for groups, for clubs, for initiatives and for situations of any kind, for example with supported employment or community living. If there is a psychiatric ward to be closed in two years and all former patients transferred to their own flats with support, Person Centred Planning will be helpful (and has proven to be so in the past).

Person Centred Planning can be useful for the development of schools, especially if they do this in a participatory way and with inclusion as a ‘North Star’ (O’Brien, Pearpoint, & Kahn, 2010: 70-71) or ‘Cruz del Sur’ (in the Global South), to guide their work. There are some examples on how schools connect planning processes with the concept of the Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Also MAPS and PATH fit as action plans with Mel Ainscow’s contribution to phases of school development in the Index if they are adapted and made accessible for children. These posters can be presented to the public for weeks in the school building, which increases the potential of being realised (Boban & Hinz, 2015). Sometimes, schools use Person Centred Thinking posters to evaluate their school development. Also, a participatory action research project with a school in Iceland used these person Centred ways for planning (Jörgensdóttir Rauterberg & Hinz, 2024). Therefore, ways of Person Centred Planning fit with processes of organisational development on different levels, they were in fact adapted from them, as you can read below.

Person Centred Planning, a practical approach – and what about evidence and theory?

Looking back to when Person Centred Planning came about, the focus was on one person, with organisational development methods in the background.

Where did it all start?

Once upon a time, there was a woman called Marsha Forest who worked at York University in Toronto. She had read some wonderful poems by a young lady, Judith Snow, and then tried to invite her to the university to talk to the students. However, she found out that this young woman lived in a senior’s home and she was totally shocked. How can it be that a young woman lives in a senior’s home? One of the reasons was that her parents were not able to care for her anymore, to turn her over in bed, for example, at night.

Then Marsha started to think about how they could support Judith so she could live as she wanted, and not be forced to live in the senior’s home. They started a circle, calling it first ‘Circle of Friends,’ and later they called it ‘Circle of Support.’ They asked several people to join, and they worked until Judith had her own flat and her own assistance there. They say this was the first person in Canada who had a personal budget and support. However, the story doesn’t end there.

Some years later, Marsha Forest got a breast cancer diagnosis. This time, Judith was the one who said: ‘Oh, let’s meet again. Let’s build a support circle and let’s think about what can be done.’ There were so many aspects to think about: Who cares for the cat? Who cares for the plants? Who cares for the fishes in the aquarium? Who goes every Friday to her mother to have tea together? Also, who’s accompanying her to her next therapy session? So, they sat down and planned for this together. Unfortunately, this story has no happy ending because Marsha passed away in 2000. Nevertheless, she had a much better quality of life than she would have had without all the people supporting her. And what about Judith? She lived until 2015 – 35 years longer than doctors had predicted.

This story shows that the start of the whole development was a very practical one in Toronto during the 1980’s (Pearpoint, 1990, 2011). People were caring for one another and supporting one another. From that starting point Person Centred Planning has spread worldwide to many countries and many different contexts.

Evidence

One of the strengths of Person Centred Planning is that it developed from practice and the way it has spread to many different parts of the world speaks to its success.

There are practitioners’ networks established, primarily in the disability sector, which support the further development of practices. For example, after two big European projects (Lunt & Hinz, 2011; Niedeck, Lindmeier, & Meyer, 2015) the New Paths to Inclusion Network includes organisations of persons with disabilities, service-providers, universities and research centres, which aim to equip practitioners with the knowledge and skills necessary to respond to the individual needs of persons with disabilities.

Although primarily focused on people with (intellectual) disabilities, there is also empirical evidence to support the use of Person Centred Planning (Claes et al., 2010; Gray & Woods, 2022; Gregory & Atkinson, 2024; Holburn, 2002; Isvan et al., 2023; McCausland et al. 2022). However, it is challenging to fully capture the outcomes of Person Centred Planning in research as some outcomes tend to be difficult to measure. For example, how can we measure the impact of the main person fulfilling a dream, or getting closer to doing so? Or how can research capture the ‘ripple effect’ on everyone in the support circle or the wider community? If we only measure employment attainment or active participation in formal learning or activities, important aspects related to human flourishing, wellbeing and quality of life get lost.

Theoretical alignments

While Person Centred Planning is not associated with one particular theory, we consider here some theories which help to further explain its success story, and why it works. The theories we have chosen to include are Carl Rogers’ humanistic and person centred approach, Otto Scharmer’s Theory U and Pierre Bourdieu’s capital theory. There is of course potential to apply several other theories which we refer to very briefly afterwards. However, for the purpose of this chapter, we have focused on three theories which we consider to be particularly relevant.

Carl Rogers’ (1961) person-centred approach has significant connections with Person Centred Planning, not only by name but also in relation to some core aspects which will be outlined shortly. Carl Rogers was an American psychologist who developed a theory from his therapeutic practice and research in the 1960’s. However, Rogers went on to contribute more broadly to the field of education through his book Freedom to Learn (Rogers & Freiberg,1994).

Central to Rogers’ humanistic and person-centred theory is the notion that we are all experts of our own lives, which is also at the heart of Person Centred Planning. It can often be challenging for professionals to step out of the role of ‘expert’ and try not to be the person with all the answers, not least for teachers who may identify as experts in their subject areas. Nonetheless, it is central that person centred work is grounded in the assumption that each person can make decisions about their own lives, albeit sometimes with the help of others. With this understanding of the person, it becomes essential that we listen to and support the person to dream.

Another assumption of Rogers’ theory is that we are all inherently motivated to self-actualise, or to realise our potential. However, Rogers suggests that growth and self-actualisation rarely happen in isolation. For a person to grow, and to live their best life, there must be mutually optimistic, warm and understanding relationships. Again, this supports the use of the ‘circle of support’ in Person Centred Planning. Rogers goes on to explain that such relationships help to develop self-awareness, self-esteem and confidence in one’s own decision making.

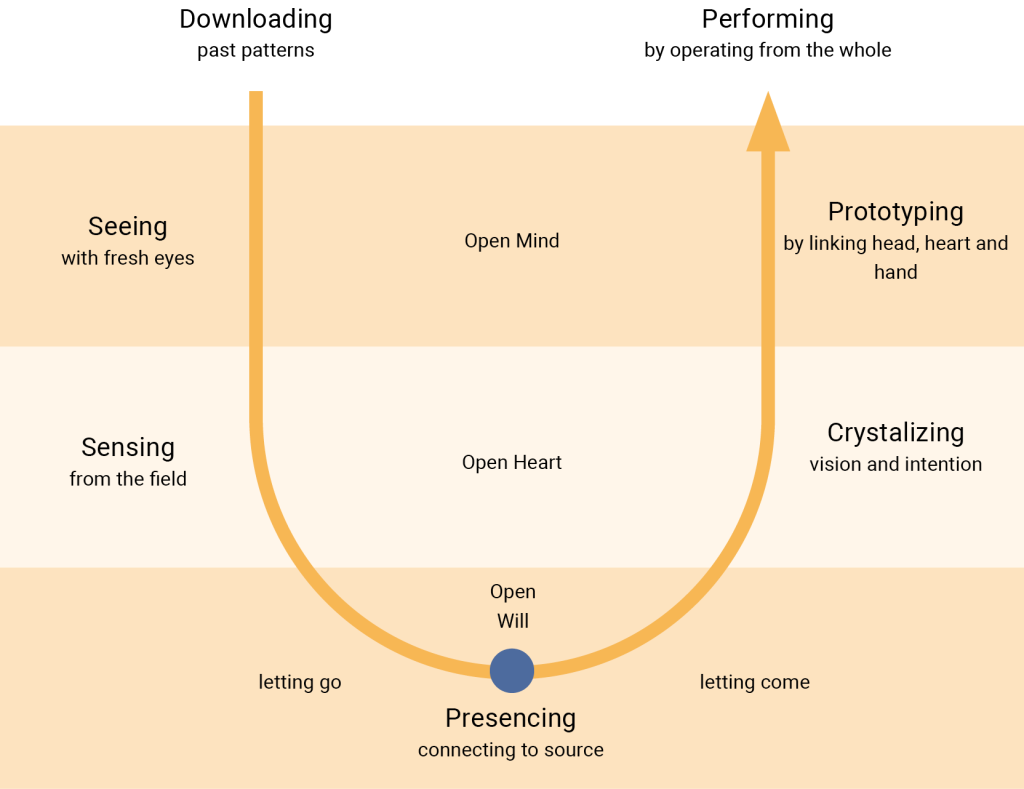

Another theory that could provide an explanation for why Person Centred Planning can be successful is Otto Scharmer’s Theory U (2009).

Figure 10: Theory U

In his theory, Otto Scharmer introduces two different ways of dealing with problems or of answering questions. The most common way is called downloading, where we apply knowledge and experience from our past (‘past patterns’) and try to solve issues based on that. It is relying on our current knowledge. From Scharmer’s point of view this creates ‘more of the same,’ leading to typical results, reproducing well-known solutions.

Person Centred Planning, as we have mentioned, relies on a common process of creativity and generating ideas. This is what Scharmer refers to in his Theory U (‘performing – by operating from the whole’). Instead of using existing knowledge and solutions, the first important step when faced with questions or issues is to let go of what we already know. He invites us to listen deeply, with an open heart, an open mind, and an open will. Instead of ‘downloading,’ people should be present and sensitive to collectively generating a culture of listening and awareness that enables new ideas and thoughts (Scharmer & Kaufer, 2013). These new ideas are, in Scharmer’s theory, “prototypes” (ibid: 21), new ideas and ways of trying to deal with the questions and challenges we are faced with. After the collective phase of listening and generating, we are then invited to start testing the prototypes, just like in PATH, when we think of goals and steps to achieve and then develop a plan of who will try what, when and with whom.

It’s listening to each other, being open to new ideas, being open to whatever wants to be born out of this process and then, putting these ideas into practice, by testing if those are possible solutions or answers to the questions that we face. Due to this large overlap of thinking and theoretic aspects, Otto Scharmer’s ‘Theory U’ has been used as a foundation for several projects implementing Person Centred Planning, for example the European Project “New Paths to InclUsion” (with capital U) and is widely used in that context (O’Brien & Mount, 2022).

Another theorist who never heard about Person Centred Planning but could, based on his ideas justify why it works, is the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In his capital theory he distinguishes between different sorts of capitals which form the position of a person in society (Bourdieu, 1986). They are interconnected and characterised (1986: 241)

- “as economic capital, which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalised in the form of property rights;

- as cultural capital, which is convertible, on certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the form of educational qualifications; and

- as social capital, made up of social obligations (‘connections’), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the forms of a title of nobility.”

If Bourdieu knew Person Centred Planning, he could argue that it is a process of increasing social and cultural capital in a very intensive way, because more people, more knowledge, and more connections with others are established through the Planning. People are more included in different contexts through the diverse group of the support circle and not just in ‘one bubble.’ Person Centred Planning has huge potential to support the main person to go through a process of growth. A person’s situation has the chance to become much better than before and enables a better position in society, not automatically but potentially. It can sometimes be seen throughout a planning meeting that the main person is almost physically growing and starting to shine (as mentioned in the example with the index cards).

There are many more theorists who would be able to argue that Person Centred Planning works if they knew about it:

- Axel Honneth (1996) could say that Person Centred Planning is something like a ‘bath’ in recognition, especially on the level of solidarity between the main person and the support circle.

- Kurt Lewin (1951) would maybe say based on his Field Theory that going through person centred processes is enriching positive ‘valences’ in the field, which strengthen the person. They could also raise awareness for individuals who act as inspiring and supportive ‘crystallisation cores,’ as newer adapters of this theory would say (Burow, 1999).

- Uri Bronfenbrenner (1979) could argue that Person Centred Planning is an example of an intense ‘proximal process,’ contributing positively towards the development of the main person by increasing competency and buffering social connections.

- Riane Eisler would say based on her partnership-domination scale that Person Centred Planning is a way of practising a very partnership oriented, egalitarian communication and co-operation with equally valued and different persons in a circle, ideally far from any tendency of domination and suppression, “nurturing our humanity” (Eisler & Fry, 2019).

- Hartmut Rosa could argue, based on his Theory of Resonance (2019) that Person Centred Planning is a great example of intensive experiences of resonance. Especially in the MAP process where supporters tell the whole circle what they would miss if the main person would not exist, which is often an emotionally overwhelming situation, including being moved to tears (as the example from Germany shows).

- Hermann Haken (1988) developed the synergy theory and emphasises co-operation, co-ordination and complementarity among various elements of disorder in the system, so that various forces within the system can gather and form a joint force, then produce an orderly state and play the overall function. He could argue that Person Centred Planning is a great example for strengthening the connection in school and beyond, building the co-operation mechanism; ensuring orderly and effective collaboration, and taking the development of children as the starting point.

Our central message, which we hope you bring with you from reading this chapter, is the importance of seeing the whole person, and their future, and to recognise that you, as a teacher, can have a significantly positive impact on others by doing this.

If you want to learn more

Here are some good places to start:

| Title / Topic | Available at |

|---|---|

| Inclusion Press, Toronto, USA A website, co-directed by Jack Pearpoint & Lynda Kahn, with articles, books, videos etc. on Person Centred Planning and more, for people in education and community settings. |

inclusion.com |

| Helen Sanderson Associates (HSA), UK A large collection of resources (reports, videos, books etc.) aimed at various settings, including schools. Many tools mentioned in this chapter are available for free here. |

www.helensandersonassociates.com |

| Personalising Education – A guide to using person-centred practices in schools, by Sanderson, Goodwin and Kinsella, A collection of person-centred thinking tools and how you can use them in a school setting |

https://www.swindon.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/10326/personalising_education_-_a_guide_to_using_person-centred_practices_in_schools.pdf |

| HWB, an education website of the Welsh Government Several documents from 2015 available to download, related to working in Person Centred ways in schools and beyond. E.g.

|

https://www.gov.wales/person-centred-reviews-guidance |

| Beth Mount’s homepage, with many books, workbooks and artistic cards etc., available to download. Primary focus is on supporting people with disabilities. | https://www.bethmount.org |

| Inclusive Solutions, an organisation based in the UK that delivers facilitation of Person Centred Planning as well as training in facilitation etc. | https://inclusive-solutions.com |

| Netzwerk Persönliche Zukunftsplanung A network across German speaking countries on Person Centred Planning |

www.persoenliche-zukunftsplanung.eu |

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- If you, as a teacher, was to implement one aspect of Person Centred Planning, what would that be?

- What could be the first step to make that happen?

- Thinking about your life so far – could you have benefitted from Person Centred Planning at some point?

- Thinking about your future – what could be a ‘great question’ for you to work on?