Section 6: Building Inclusive School Cultures and Policies

Advancing Inclusive Education: Policy, Practice and Structural Changes’

Jean Karl Grech; Nika Maglaperidze; and Akangshya Bordoloi

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“We would first like to bring in the case study of Malala Yousafzai from Pakistan a 17-year-old education activist who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 for her work in female education which makes her the world’s youngest Nobel Prize Laureate. She is credited with highlighting the importance of an inclusive education policy. However, we would like to refocus the attention towards her father Ziauddin Yousafzai who was an education activist himself and worked vehemently towards bringing about equal basic education for all, including women. It was and still is considered quite a radical perspective in a Taliban-dominated country like Pakistan that justifies violence against anyone who dares to defy their radical Islamic policies. However, her father’s bravery and zeal for inclusive education motivated Malala to bravely face all kinds of discrimination and violence-including getting shot by a Taliban gunman (UN, 2017).

If we consider Malala and her father to be conscious educators then, it is crucial that we chart out what makes them relevant educators and how can those characteristics be inculcated among young researchers and intending educators. It would then help us in understanding the significance and impact that our roles as educators can have on policy in education.”

Initial questions

In this chapter, you will find answers to the following questions:

- What are policies and how should we read them?

- What is the contemporary significance of an inclusive teacher education policy and what impact do we expect from such an inclusive policy?

- In what ways do structural disadvantages manifest within educational institutions, and how do existing educational policies both contribute to and fail to address these inequalities, thereby impacting the realisation of inclusive education?

Introduction to Topic

There are an estimated 240 million children with disabilities worldwide. Yet children with disabilities or any other ‘different kinds’ of children are often overlooked in policymaking, thereby, limiting their access to education and their ability to participate in social economic and political life. Worldwide, these children are among the most likely to be out of school and/or face discrimination, stigmatisation and violence. Robbed of their right to receive a proper education, such children are also often denied the chance to take part in their community activities, the workforce and the policy decisions that mostly affect them. Inclusive education is thus considered as the most effective way to give all children a fair chance to go to school, learn and develop the skills they need to thrive. By maintaining a focus on transforming teachers/educators into active agents while formulating policy and implementing the curriculum-inclusive education very simply means that children from different backgrounds can grow and learn in the same classroom. The concept is popularised widely by UNICEF, and it has requested all the member states to implement it in ways that would address their distinct needs (UNICEF, 2001).

The most crucial, however, is the outcomes of the 48th Session of the International Conference on Education (ICE) held in Geneva in November 2008. It presented a broadened concept of inclusive education as a holistic reform strategy for education systems aiming to achieve quality education for all. They are of the view that “a broadened concept of inclusive education can be viewed as a general guiding principle to strengthen education for sustainable development, lifelong learning for all and equal access of all levels of society to learning opportunities” (UNESCO, 2008). Within the context of this broadened concept of inclusive education, a key role for inclusive teachers has been recognised and developed around the need to meet diverse learner’s needs and promote inclusion. This consensus is built on a rights-based perspective of education and considers the startling numbers of learners excluded from education around the world (Opertti and Brady, 2011).

This has led to the right to basic and equal education irrespective of age, class, geographical location, culture, politics, religion and other factors to be lacking in many countries even in the contemporary times. It might be quite difficult to chart out the core reason behind this due to the complex intersectionality shared by the three major institutions of society, i.e law, politics (both domestic and international) and religion. However, key issues include the widening gap in learning outcomes, that is closely related to social and economic conditions; the increasing diversity of classrooms with respect to cultural and linguistic origins; the shortage of experienced teachers working where they are needed and how their services are required; the difficulties in recruiting teachers from diverse social backgrounds; and the low pay and status of the teaching profession (Opertti and Brady, 2011). Thus, through this proposed policy, we are trying to articulate and justify this approach and create an inclusive teaching policy that can address the contemporary distinct needs of its students and break the power imbalance between the educator and the students.

Key aspects

Structural Disadvantages

Having explored the broader concept of inclusive education and the role of policy in addressing structural disadvantages, this chapter now focuses on the specific forms these disadvantages can take. In this next section, the concept of ‘Structural Disadvantages’ in education is explored in more depth. This exposes common mistakes in policy, where surface-level goals don’t match the realities students often face.

Structural disadvantage in education describes the circumstances where specific groups of children and young people experience marginalisation or disadvantage within educational institutions like schools, universities, kindergartens, etc. This is often a result of social divisions that create and perpetuate inequalities (Unterhalter, 2021). These are students who often have limited access to educational opportunities or are subjected to low-quality education (Matsumoto, 2013). These disadvantages are entrenched in societal structures and exacerbated by ineffective education policies, permeating the very classrooms where we teach, and as a result inhibiting the implementation of inclusive education. As a teacher, you will likely observe that these structural disadvantages originate due to various factors, including your students’ socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, gender, disability, and geographical location, among others. It is also important to draw our attention to how inequalities can also be embedded into our teaching practice (Unterhalter, 2021). Even within deeply unequal systems, individuals strive to combat structural disadvantages in education on a daily basis. A powerful example of this is Malala Yousafzai and her father Ziauddin, who defied entrenched gender restrictions on education in Pakistan. Despite immense barriers, they championed equal basic education for all, including women. This case exposes how the transformative power of education depends on policy shifts; even the bravest individuals struggle alone against systemic barriers.

Intersectionality offers a lens to examine the complex interplay of these different factors and illustrates the multi-faceted nature of inequalities and how they can play out in your classroom and the school (Crenshaw, 1990). This intersectional lens reveals limitations in policy responses that treat each disadvantage in isolation (ethnicity-focused programmes that ignore poverty, etc.). Further, it underscores how socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, gender, and geography can intersect and interact in ways that exacerbate educational disparities. For instance, a student from a low-income, ethnic minority background might face compounded challenges due to both economic constraints and systemic racial biases. Similarly, gender disparities in education can be influenced by a combination of societal norms, educational policies, and socioeconomic factors, which can vary significantly across different geographical contexts. Furthermore, these policy-exacerbated disparities are not isolated but can reinforce each other, creating a complex web of inequality that is deeply embedded in our educational systems (Matsumoto, 2013; Unterhalter, 2021).

A wealth of research evidence now suggests that socioeconomic disparities have a broad range of impacts on children’s learning, with the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage being felt both within and outside of school (Hirsch, 2007). One of the most conspicuous manifestations of these disadvantages in schools and classrooms is through educational outcomes. In fact, it’s striking that 60% of the variance in assessment outcomes can be attributed to out-of-school factors, such as those previously mentioned (Haertel, 2013). For instance, children from impoverished and disadvantaged backgrounds typically perform significantly worse than their peers from more advantaged backgrounds. A primary contributor to child poverty in many instances is the lack of opportunities available to parents with limited skills and qualifications. Such parents are less likely to be employed and have the necessary income and resources to meet the financial demands of raising a family.

Consequently, children from disadvantaged households are less likely to acquire the necessary qualifications that could help them escape the cycle of poverty and achieve social mobility. This highlights the failure of our system to address the root causes of underachievement. Current policies often focus on individual achievement within the school system, neglecting the broader societal factors that contribute to disadvantage. This narrow approach fails to address the root causes and perpetuates existing inequalities. If societal support to overcome economic disadvantage is absent, even motivated students suffer, revealing the need for holistic policies beyond the classroom. These systemic inequities manifest in varied ways across contexts: In wealthy nations, parental lack of opportunity might prevent buying school supplies and resources. Additionally, in low-income countries, such as Kenya, parents with low literacy levels may not fully understand the long-term benefits education offers their child. This lack of understanding can sometimes lead to children not attending school consistently or at all, perpetuating the cycle of poverty across generations (Unterhalter et al., 2012). These varied socioeconomic barriers illustrate how disadvantage in education has different roots depending on context, yet with sadly similar consequences. In response to these socioeconomic disadvantages, certain policies have been enacted to address these and other educational inequalities. For instance, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education enacted in India can serve as a good example as was mentioned earlier in this chapter.

Building on the idea that educational outcomes vary among different social groups, particularly those from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (Hirsch, 2007), it is important to delve deeper, albeit briefly, into the mechanisms behind these disparities. One of the most prominent factors is represented in the concept of racialisation, which is when people’s relationships with each other are influenced by their racial identities, which has a big impact on education (Bajaj & Scott, 2022). Racialisation leads to systemic biases and prejudices that are deeply embedded in educational systems, biases often left unaddressed by current policies due to a focus on individual teacher ‘bad apples’ rather than institutional failings. This bias affects teacher responses, grading, limiting student belief in their own ability regardless of true effort, affecting the quality of education received by students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. This can manifest in various ways, such as differential access to resources, biased curriculum content, and discriminatory practices within the school environment (ibid.). Further, in some instances, some ethnic groups tend to be positioned far from the centre of power, which will affect their access to both the quality of schooling they receive and the curriculum that alienates them and omits material of cultural significance for them.

Gender differences in education persist even in high-income nations. For example, in Germany, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, boys are more likely to leave school prematurely compared to girls, and girls typically achieve higher school grades than boys. However, interestingly, in these same countries, girls are less likely than boys to pursue higher education several years later (Hadjar & Buchmann, 2016(a); 2016(b)). This trend coincides with a lack of robust government support systems, such as affordable childcare or flexible work arrangements, which disproportionately hinder a mothers’ pursuit of higher education. This pattern can be attributed to a combination of intersectional factors. Socialisation and cultural norms, educational systems and policies, and socioeconomic factors play significant roles in these gender disparities. Societal expectations and stereotypes about gender roles can influence students’ educational choices and performance. The structure of educational systems, particularly those that sort students into different tracks early (as in Germany, Austria and Switzerland), can exacerbate these inequalities. Lastly, socioeconomic factors, such as increased educational motivation among girls and women due to expanding opportunities in the labour market, also contribute to these trends.

This focus on enrolment reveals a common limitation in education policy: despite good intentions, strategies focused on surface-level equality often bypass deeper structural causes (Unterhalter, 2008). For instance, the ‘get girls in’ mindset overlooks how gender bias impacts student experience itself and persists well after graduation due to limited career opportunities and discriminatory hiring practices. This mismatch between stated equality goals and the barriers girls actually face underscores how structural change isn’t achieved through simplistic initiatives, making deeper reform strategies vital.

Another significant area of structural disadvantage in education pertains to students with disabilities, who often face multiple challenges that can limit their access to quality education even after multiple charters on the right to quality education in a number of human rights conventions such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1989) and the Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons (UN, 1975). For example, the development of mass education systems throughout the 20th century where grand proclamations of education for all in truth meant education for some (De Bruin, 2021), reflecting deeply unequal policy implementation. While international commitments exist, insufficient funding and flawed inclusion programmes reveal low policy priority for true empowerment. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2017), in Cambodia, the out-of-school rate for children with a disability is 57%, which stands in a stark contrast to the 7% rate for neuro-typical children. Similarly, in the Maldives and Uganda, children with a disability are more than twice as likely to be out of school. Furthermore, only 44% of Cambodian adolescents with disabilities complete primary education, compared to 72% of their neuor-typical counterparts. Even in Western nations, the situation is far from ideal, for instance, in England, students with special needs were more than nine times likely to face permanent exclusion (UNESCO, 2020). These disparities underscore the structural disadvantages that children with disabilities encounter in accessing education.

Moreover, the challenges do not just end with access to education. Once in school, students with disabilities often face additional obstacles. For instance, teachers may lack the necessary training to effectively teach these students, which leads to unclear responsibilities and limited collaboration with support personnel. Discrimination and segregation can further exacerbate feelings of exclusion. Inadequate resources, inconsistent policies and practices, and dismissive and indifferent attitudes towards inclusion can also impact the quality of education received by students with disabilities and their overall school experience (UNESCO, 2020). These factors create a complex web of challenges that can significantly impact the educational experiences and outcomes of students with disabilities.

This is also evident when looking into the experiences of LGBTIQ+ students in schools and the likelihood of increased absenteeism and thus the limited access to education this has for such individuals. This is likely attributed to varying factors mainly to do with safety in schools and visibility within schools. As Goldstein, Russell & Daley (2007) explain, safety refers here to the ability for all students including LGBTIQ+ students to feel safe being themselves and understanding their identity in school. On the other hand, visibility refers to schools clearly being inclusive and welcoming to their LGBTIQ+ communities through teaching and social practices which are visible in the school. While safety for LGBTIQ+ students is on the rise (ILGA, 2022), policy and pedagogical practices, which ensure the visibility just described and inclusive sex education on gender, sex and sexuality, remain a big challenge in schools. This is often a result of a gradual politicisation of the subject which leads to either policymakers remaining silent on the matter or otherwise enacting specific policies to regulate and exclude the visibility of the LGBTIQ+ community in schools in order to gain political popularity.

Building on the understanding that structural flaws hinder educational access and equality, we must examine how these injustices materialise within the seemingly inert walls of the classroom. Curriculum, far from a neutral tool, acts as a vessel for deeply embedded policy priorities. Indeed, Basil Bernstein (2003:77) argued that ‘how a society selects, classifies, distributes, transmits and evaluates the educational knowledge it considers to be public, reflects both the distribution of power and the principles of social control.’ Through textbook omissions of some histories, to rigid curriculum pacing mandates struggling students are left with no recourse, however policy creates the illusion of equal opportunity (Bertram, 2012). Teachers are then scapegoated as the problem, when it’s precisely a lack of anti-racist resources or flexibility in policy that perpetuates inequity. Decisions regarding which historical figures, scientific disciplines, and literary voices matter are not made in a vacuum. They are enshrined in policy under the guise of objective knowledge, potentially perpetuating systemic exclusion.

The Role of Teachers and Policymakers

As an educator, it is crucial to recognise that teachers, while critical agents in fostering inclusive learning environments, often navigate complex limitations imposed by these very structures. While recognising and understanding the specific challenges their students face is crucial, their ability to make significant curricular changes can be constrained by factors like limited resources, mandated standardised testing regimes, and a lack of professional development opportunities focused on culturally responsive pedagogy. Adding to the challenges faced by teachers is the common practice of policymakers and reformers to exclude teachers and students from key decision-making processes directly related to their profession. This is often accompanied by undervaluing teachers’ expertise and professionalism, leading to their opinions being dismissed out of hand.

Around the world, there is a rising trend of distrust towards teachers, with policies increasingly designed to scapegoat them, subject them to surveillance, and compel them to adhere strictly to teacher-proof lesson plans and curricula (Niesz, 2018). In this context, teacher agency becomes a nuanced concept (see below), requiring not just individual initiative but also systemic support and policy shifts that set educators free to challenge the status quo and create truly equitable learning experiences. Despite the daunting nature of these structural disadvantages, teaching remains our most promising activity in addressing them so far as education policy is concerned (Jones, 2019; Wiliam, 2018). For example, developing pre-service teachers who are socially just in their beliefs and practices has been emphasised and to this end, numerous relevant and potentially impactful policy strategies have been suggested to equip teachers with the necessary tools to navigate and mitigate the challenges presented by the structural disadvantages and inequalities prevalent in our schools (Mills & Ballantyne, 2016). For example, Berliner (2019:187) proposes that in addition to teachers acquiring in-depth curricular content knowledge, instructional skills and classroom management skills, teachers must also be trained ‘to promote the success of their students by understanding, responding to, and influencing the larger political, social, economic, legal, and cultural context in which they lived and work.’

In response to all of these challenges, we think that the teachers themselves should feel empowered to achieve agency to affect change on multiple levels starting from the classroom and school level and extending their impact to the structural and systemic levels. We believe that teacher education policy could be a way for achieving this. For example, Berliner (2019) advocates for teacher education policy to emphasise the social activist element for teachers to become better representatives of students and their families and indeed themselves. Teacher education institutions need to stress the politics of education as much as more technical aspects of teaching and learning (Jones, 2019). Given the significant influence of curriculum in educational settings, it is crucial for teachers to achieve agency and become advocates for liberatory curriculum (Le Fevre et al., 2016). This involves challenging narrowly defined, standardised, and teacher-proof curricula. By doing so, teachers can take on essential roles as curriculum activists, confronting problematic policies and crafting a curriculum that addresses the needs of their students and communities.

Education, with its multifaceted nature, necessitates the formulation of policies to reduce its complexities and make it more manageable. However, an over-simplification and reduction of these complexities can lead to an education system that is overly focused on outcomes, thereby risking the neglect of inclusive teaching practices. Therefore, a balanced approach is essential in the development and implementation of education policies. Moreover, policymaking is not a value-neutral process. It is deeply influenced by the values, intentions, and perspectives of those who craft them. Hence, it is crucial to critically examine who is involved in policymaking, how these policies are formulated, and the purposes they are intended to serve. This nuanced understanding can help ensure that policies are not only effective but also equitable, promoting an education system that truly caters to the diverse needs of all students.

As we delve deeper into the complexities of structural disadvantages in education, it becomes increasingly clear that these issues are not confined to the classroom but are deeply intertwined with broader societal structures and policies. The role of policy in shaping educational practices and outcomes cannot be overstated. Policies determine not only what is taught in schools but also how it is taught, and by whom. They are the invisible hands that guide the actions of teachers and the experiences of students in the classroom. However, the process of policymaking is not a straightforward one. It involves a multitude of stakeholders, each with their own interests, perspectives, and power dynamics. The following section will explore the intricate world of educational policies, shedding light on who gets to decide what is included in them and how they impact the everyday realities of teachers and students. This chapter will also delve into the role of various stakeholders, from local institutions to supra-entities, in shaping educational policies and practices. By understanding these dynamics, educators can better navigate the policy landscape and advocate for more equitable and inclusive educational practices.

The Role of Teachers and Policymakers

As an educator, it is critical to be aware of the causes and effects of these systemic disadvantages. Being cognisant of these allows you to better understand the specific challenges your students may be facing and use your discretion as a teacher to make appropriate curricular changes that address each of your student’s needs. It also equips you with critical insights to advocate for crucial changes within your school and the wider education system that could help alleviate some of the disadvantages faced by students and the challenges you will face as an educator. Despite the daunting nature of these structural disadvantages, teaching remains our most promising activity in addressing them so far as education policy is concerned (Jones, 2019; Haertel, 2013). For example, developing preservice teachers who are socially just in their beliefs and practices has been emphasised and to this end, numerous relevant and potentially impactful policy strategies have been suggested to equip teachers with the necessary tools to navigate and mitigate the challenges presented by the structural disadvantages and inequalities prevalent in our schools (Mills & Ballantyne, 2016). For example, Berliner (2019:187) proposes that in addition to teachers acquiring in-depth curricular content knowledge, instructional skills and classroom management skills, teachers must also be trained ‘to promote the success of their students by understanding, responding to, and influencing the larger political, social, economic, legal, and cultural context in which they lived and work.’

Adding to the challenges faced by teachers is the common practice of policymakers and reformers to exclude teachers from key decision-making processes directly related to their profession. This is often accompanied by undervaluing teachers’ expertise and professionalism, leading to their opinions being dismissed out of hand. Around the world, there is a rising trend of distrust towards teachers, with policies increasingly designed to scapegoat them, subject them to surveillance, and compel them to adhere strictly to teacher-proof lesson plans and curricula (Niesz, 2018).

In response to all of this, we think that the teachers themselves should feel empowered to exercise agency to affect change on multiple levels starting from the classroom and school level and extending their impact to the structural and systemic levels. We believe that teacher education policy could be a way to achieving this. For example, Berliner (2019) advocates for teacher education policy to emphasise the social activist element for teachers to become better representatives of students and their families and indeed themselves. Teacher education institutions need to stress the politics of education as much as more technical aspects of teaching and learning (Jones, 2019). Given the significant influence of curriculum in educational settings, it is crucial for teachers to exercise their agency and become advocates for liberatory curriculum (Le Fevre et al., 2016). This involves challenging narrowly defined, standardised, and teacher-proof curricula. By doing so, teachers can take on essential roles as curriculum activists, confronting problematic policies and crafting curricula that cater for the needs of their students, and which are created together with the students.

Education, with its multifaceted nature, necessitates the formulation of policies to reduce its complexities and make it more manageable. However, an over-simplification and reduction of these complexities can lead to an education system that is overly focused on outcomes, thereby risking the neglect of inclusive teaching practices. Therefore, a balanced approach is essential in the development and implementation of education policies. Moreover, policymaking is not a value-neutral process. It is deeply influenced by the values, intentions, and perspectives of those who craft them. Hence, it is crucial to critically examine who is involved in policymaking, how these policies are formulated, and the purposes they are intended to serve. This nuanced understanding can help ensure that policies are not only effective but also equitable, promoting an education system that truly caters to the diverse needs of all students.

As we delve deeper into the complexities of structural disadvantages in education, it becomes increasingly clear that these issues are not confined to the classroom but are deeply intertwined with broader societal structures and policies. The role of policy in shaping educational practices and outcomes cannot be overstated. Policies determine not only what is taught in schools but also how it is taught, and by whom. They are the invisible hands that guide the actions of teachers and the experiences of students in the classroom. However, the process of policymaking is not a straightforward one. It involves a multitude of stakeholders, each with their own interests, perspectives, and power dynamics. In the following section, we will explore the intricate world of educational policies, shedding light on who gets to decide what is included in them and how they impact the everyday realities of teachers and students. We will delve into the role of various stakeholders, from local institutions to supra-entities, in shaping educational policies and practices. By understanding these dynamics, educators can better navigate the policy landscape and advocate for more equitable and inclusive educational practices.

What are policies and who gets to decide what is included in them?

Although policies shape a lot of the subjects and styles of teaching that teachers adopt in schools, teachers might not know much about the powerful role these documents play in institutions of education around the world. This is especially the case if policy development and policy implementation are not respectively discussed and reflected on as topics during one’s initial teacher training education. However, educators need to recognise that ‘[education] does not exist in a vacuum – it is exercised in a policy context, shaped decisively by its historical and cultural location’ (Bell & Stevenson, 2006:7). Thus, as a profession, teaching is not an act which relies only on the students and the teacher in a classroom but is a product of different forces acting on it to achieve their desired outcomes. The forces or entities which shape what takes place in schools are referred to as, stakeholders, meaning that they have a share, interest, or involvement in deciding what is taught in schools, how it is taught and to whom. Some examples of stakeholders include ministries, local or international organisations, and other private entities.

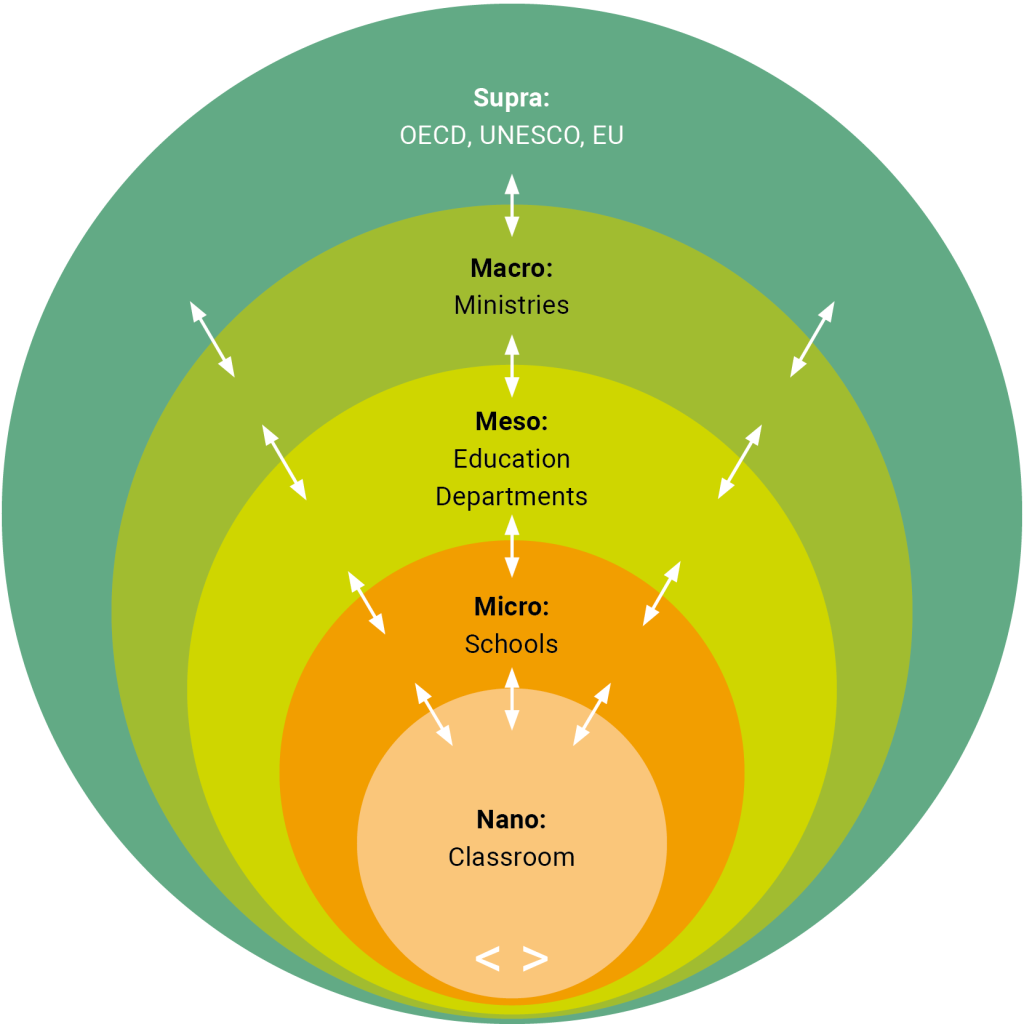

The example mentioned above is only a small sample of how stakeholders impact the learning that takes place in formal schooling through curricula. Generally, this applies to all areas of schooling which are largely organised and maintained by a government or another institution, including inclusion and addressing structural disadvantages such as the ones described in the previous section. As schools directly engage with their policies, they must also fulfil those established by external forces. External forces do not only refer to local institutions such as the government but include different entities which also extend outside of national borders. Priestley et al. (2021) refers to these entities as sites of activity and classifies them into five main levels. At the heart of this model lies the educator and the students in the classroom, but by looking outwards, one may note how the events taking place at the nano level are part of a web of established policies by different entities. Who are these entities?

The role of supra-entities in policymaking is usually to do with influencing and flowing ideas across different nations. A clear example of these entities is UNESCO which we have mentioned in the example case above. By establishing competency frameworks, country reviews and standardised objectives for national policies to absorb, supra-entities are active key players in various education systems around the world. This is evident through popular country reviews which compare countries participating in international studies such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), conducted by the OECD. Since the year 2000 PISA has conducted seven rounds of assessments which focus on literacy, mathematics, and science with the aim of testing the knowledge and skills of the students from participating countries with a metric that is collectively agreed upon (Schleicher, 2019:3). Consequently, the results obtained by low-performing countries have over the years pushed national policies to adopt strategies and targets which are believed to be effectively working in other countries topping the charts of PISA and other similar studies. This process is usually known as policy borrowing and has over the years been increasingly used in education as countries adopt strategies and programs which were proven successful elsewhere (Mundy & Verger, 2016: 375-6).

Figure 1: The five main levels educational development

Therefore, the OECD, through PISA, is policy-oriented because it provides scores and analyses to guide decisions taken by education entities in the participating countries. Despite not having direct legislative and financial power on the other levels, the OECD has contributed to many changes in policies and curricula around the world. The same cannot be said for entities such as the World Bank which is, ‘the largest single international provider of development finance to governments … and source of education finance’ (Mundy & Verger, 2016: 335). The World Bank has since the 1970’s obtained direct financial power as it establishes policy requirements as part of financial packages dealing with different countries (Mundy & Verger, 2016:339). This influence on different states around the world stems from the belief that such institutions are assessing and ensuring co-operation and increasing efficiency in a globalised world driven by large economic forces. This is visible in some of the policies that the World Bank has pushed which include ensuring equal education for all, improving learning outcomes and quality of education, developing early childhood programmes, and focusing on skill-based vocational education. These are said to ensure the needs of the future labour market are met. Having said this, bearing such institutional power over curricula in schools requires extensive critique. This is explored in the upcoming parts of this paper.

On a macro level the policies implemented by the ministries do not only consider the directives and results published by the supranational entities mentioned above. Ministries must also consider the input of different stakeholders involved on a national level. These include the government and its ministries, local universities, teachers’ organisations, unions, and other local entities. It is through this level that, ‘state-mandated programs of study present authoritative statements about the social distribution of knowledge, attitudes, and competencies seen as appropriate to populations of students’ (Priestly et al, 2021:17). Once a policy is designed and agreed upon by the stakeholders, Education Departments, or broadly the mesosystem, ensure that these policies are implemented by directly supporting schools and their staff members. Usually, departments organise teacher training, post-implementation assessments and observations to monitor the effectiveness of a particular policy. In sum, ‘meso-curriculum making sits between the production of policy … and the curriculum making arenas in practice settings such as schools’ (Priestly et al, 2021:19).

Although these levels have been explained here in succession it is important to bear in mind that they collectively operate with one another and influence each other. In fact, these levels can be defined as sites of activity, metaphorically presented by a spider’s web. ‘Policy making may be informed in a particular context by both supra discourses and by diverse local imperatives [and] a variety of mediating factors’ (Priestly, 2021:12-14). This captures the complexity behind the transactions that happen between each of the levels described. Moreover, it is important for the reader to grasp how such contentious, interconnected, and multidimensional arenas, do not necessarily produce and implement policies successfully all the time (Honig, 2006:2). In fact, as identified in the previous section, policies can have a devastating impact on students, teachers and/or even a state’s education system.

Where does the teacher fit into all this?

However, if formulated and implemented inclusively, policy also has the capacity to bring about great positive changes with a focus on a more wholesome welfare for the targeted population. For example, when we bring back the discussion about Malala and how she was influenced by her father to brave against all odds and fight for a change in the education policy of Pakistan we witness the importance of the educator as an active agent, and the range of possibilities that opens because of it. Her story also proves the urgent need for an inclusive education in government education policies of all countries. This we believe will not only be able to challenge the established, often discriminatory status quo during policy formation, but if implemented properly, would also be able to address the various social evils of the respective countries-exactly like Malala (UN, 2017).

So, what is required here is focus on four key areas that has been promoted by UNICEF:

- Advocacy: that promotes inclusive education in discussions, high level events, and other forms of outreach geared towards policymakers and the general public.

- Awareness-raising: that shines a spotlight on the needs of children with special needs by conducting research and hosting roundtable workshops and other events for government partners.

- Capacity-building: that builds the capacity of education systems in participating countries by training teachers, administrators, and communities while also providing technical assistance to governments.

- Implementation support: to monitor and evaluate partner countries to close the implementation gap between policy and practise (UNICEF, 2005).

In addition to that, UNICEF has also published a checklist of actions that all participating governments must comply with to make inclusive education a reality. Known as ‘progressive realisation’ it includes: committing all government departments to work towards active inclusion, introducing laws and policies to end discrimination and guarantee the right to inclusive education, deciding the course of action, timetable and a curriculum for introducing inclusive education, ensuring that enough resources are available to enable the transition to inclusion, collecting data and measuring progress and growth, providing early childhood care and education, providing adequate teacher training for inclusive education, introducing inclusive testing and assessment and introducing complaint procedures (UNICEF, 2017). Now, although not everything might be possible straight away, there are certain things that States could act on immediately. It primarily includes compulsory, free primary education for all-much like the RTE Act in India, proper sensitisation programs for all so that children from all kinds of backgrounds feel welcomed, and transforming teachers/educators to be an active agent in both policy formulation and implementation (UNICEF, 2017).

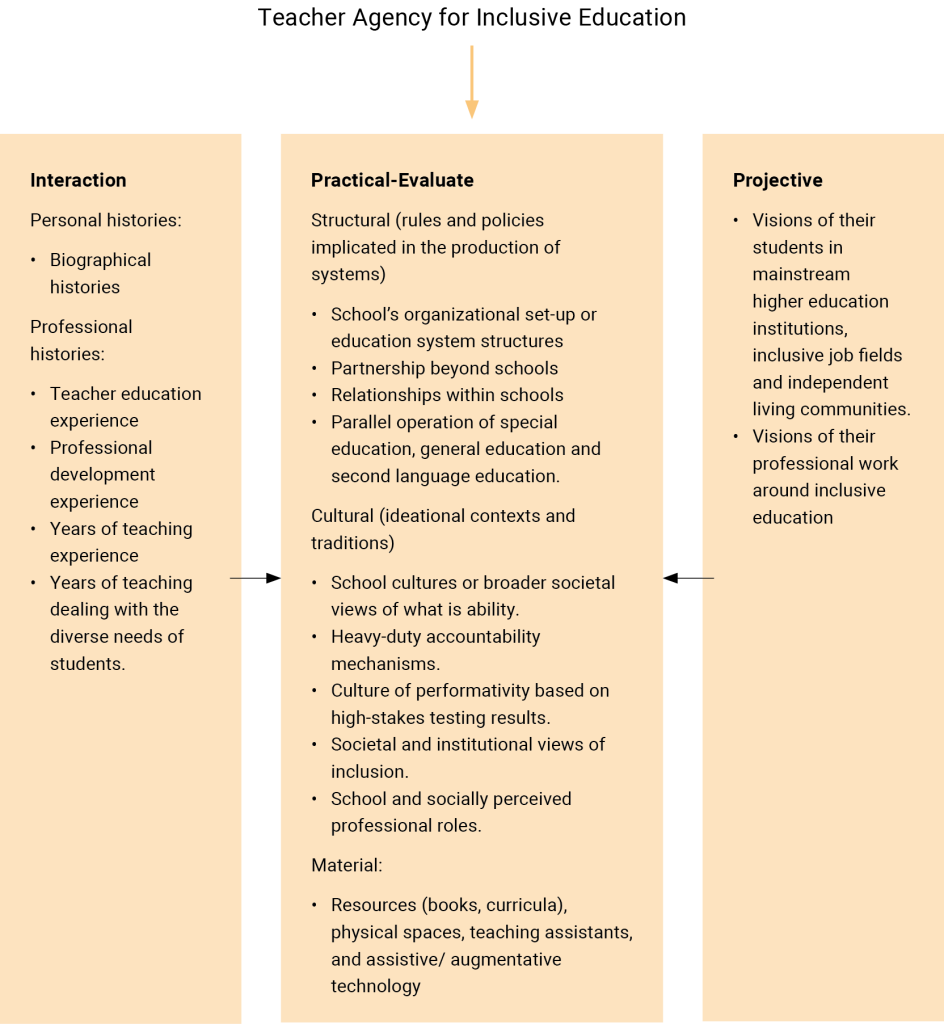

It is the third point that our proposed policy is focussing more on. Taking inspiration from Foucault’s very famous argument of ‘knowledge being power, wherein power is based on knowledge and makes use of it to create and recreate its own field of exercise’ (Hewett 2004:10). We argue that all educators need, can and should, play a powerful active role in promoting societal inclusion and equity for all kinds of learners (Li and Ruppar, 2021). The common responsibilities/expectations would include being included during policy formulation, possessing the power and recognition in amending existing education policy, being provided the space and autonomy to implement said policies in ways that fits the demography and needs of their children, and having a safe space and/or creating opportunities to familiarise themselves with the backgrounds and distinct needs of the children in their class. However, as teacher agency is considered under-theorised and variously constructed in the education reform literature, conceptual models of agency have been developed by drawing on broader theories of human and professional agencies. Drawing from Li and Ruppar’s (2021) work on attempting to map out the empirical significance of theorising teacher agency, we would like to chart out the factors that have a strong influence on how teacher agency is understood and practised:

Figure 2: Teacher Agency for Inclusive Education

The above figure provides an empirical framework that could be used to establish the practicality and relevance of the theory of teacher agency in inclusive education. Moreover, the adapted conceptual framework follows socio-cultural theory, which treats teacher agency as a result of the interplay among individual teacher’s capacity and environmental conditions, along with the interaction of the teacher’s past experiences, current practise and future orientations. We believe that an explicit way of theorising teacher agency for inclusive education can help future empirical studies treat teacher agency as ‘an analytical category in its own right’ and hence, crucial while discussing education policy. It would also assist in cementing the proposal of including teachers/educator’s opinions during policy formulation while providing flexible spaces in the curriculum for the policies to be implemented in what ever unique and creative ways the teachers/educators deem to be fit for its students (Li and Ruppar, 2021). Such an approach will be able to contribute towards a more sensitive and inclusive social education policy that is global (popularised by British sociologist Roland Robertson in the 1990s and later developed by Zygmunt Bauman) in its approach (Mambrol, 2017).

Why should a teacher want to know about and be involved in policymaking?

Before proceeding with this section, let’s take some time to revisit what has been established thus far in this paper. The example case mentioned in the first section refers to a policy for inclusion in education as established by UNESCO. We later learned that the latter is one of the many supra-national entities which, as established in part three, has the capacity to influence goals for education on a global scale. We saw this in practice through India’s Education Act of 2009, which was introduced to absorb some of these principles established by UNESCO. The second section sheds light on different types of structural disadvantages that students in our schools are still experiencing because of varying factors which policies have either failed to recognise or address in their implementation. We then took a closer look into the different stakeholders that exist and influence policy in education. These ranged from international entities with direct or indirect financial power over education, to also local ministries, institutions, and organisations. This large and complex web of different sites influencing education can often feel daunting and exclusive of the teachers’ experiences and needs in schools. It often feels that decisions and new directives come and go and teachers bearing the change and challenges in the classroom are not considered in the process of designing new policies and strategies. This is best summed by Robinson in saying that, historically, ‘the most consistent overarching theme which has dominated teacher education has been its relationship to the state. It has been externally controlled and shaped by governments and their agencies – and not by the teaching profession itself’ (UNESCO, 2017:16).

Therefore, educators should know about policy because, despite their potentially good intentions, such institutional documents, may not necessarily be as effective as intended. This could be a result of different factors ranging from inadequate funding, potential clashes between stakeholders involved, or expediently misguided strategies. The latter is alarming since it is more likely to be less effective for the institutionally disadvantaged groups mentioned above.Therefore, policies are in themselves, powerful and political tools which may not necessarily be used to ensure equal access to education. On the contrary, as Malala’s story very well portrays, policies and laws can be used to further solidify levels of structural disadvantages to ensure an individual or group’s dominance over another. This becomes ever more likely when the complex web of sites influencing policies becomes increasingly inundated with different forces acting on it, most of which coming from outside of the classroom.

On the other hand, despite their often-felt sense of external and authoritative force, policies can be instrumental in addressing these difficulties especially when teachers are not just implementors of their goals but also writers and thus, active agents in the decision making. In Malala and her father’s actions, we can witness the impact that praxis and active involvement can have in addressing structural disadvantages through education. This is why the previous section gradually shifted our focus to teachers as active agents and not just deliverers of content. Teaching, in its nature, gives educators the opportunity to interact with the structural disadvantages described above and understand the impact and challenges that students face. Freire (1970) sees both the students and the teachers as constructors of knowledge together through interaction. If it were not for human interactions, teaching would be lifeless and thus policies should reflect that same interaction.

Therefore, similar to the previous section, we have gradually shifted our perspective on policy to a critical one whereby the educator is encouraged to not only read and be aware of policy but to reflect on its point of being. We aspire to have the readers appreciate their potential not only as educators with students simply following established forms of knowledge and pedagogical practices, but as powerful professionals striving to improve the lives of others because they have lived and learned about others. ‘For the critic, the important thing is the continuing transformation of reality, in the continuing humaniaation of men’ (Freire, 1970:65). This is why the educator is here encouraged to question who is benefiting the most from the currently established systems designed over the years through curricula and policies as we know them and how these can be changed to benefit all through education. Thus, as we proceed to the coming sections, we aim for the reader to further equip themselves with strategies and tools they may use to become active agents in policymaking, to become critical readers of policies and frameworks, and consequently key contributors in this process.

How can a teacher become a reflective and critical agent in the decision-making process?

Understanding the complex web of the different stakeholders involved in writing up and implementing policies can be a daunting task. To critically do this may feel even more challenging for an educator who aspires to address the needs of their students but is too perplexed by a system which feels bigger and stronger than them. However, this does not need to be the case, because teachers can and have become active agentic individuals in changing the system and not just implementing it. Critically reading policy is far from an untapped field in academia and has over the last thirty years greatly expanded to investigate the ‘opaque as well as transparent structural relationships of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in [the] language’ contained within policy documents (Blommaert & Bulcaen, 2000:448).

The field is denoted by the term Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) and it is particularly appropriate for critical analysis of policies because it allows a detailed investigation of the relationship of language to other social processes, and of how language works within power relations’ (Taylor, 2004: 436). In practice, this means that words contained in policies are no longer just read but examined for their implications and the powers they establish. Through a CDA framework for a systematic analysis, [one] can go beyond speculation and demonstrate how policy texts work’ (Taylor, 2004: 437). Critical discourse is mainly two types: The first sees the analysis take place at a textual level where the words, pictures, and language used are analysed. For example, one may investigate the number of times words such as “inclusion” and “needs” are used in a document and reflect on how much importance is being given to these words. Otherwise, one may investigate the style of language being used in a policy; is it authoritative in its style of writing by using declarations such as, “teachers must” or is it emancipatory by including words such as, “we need” or “we should” (Simons, Olssen & Peters, 2009).

The second, broader critical analysis examines the social and historical context of the space in which the policy was implemented. In sum, this does not analyse the words themselves but the power that lies within them, those who wrote them, and the context in which they were made. Policies are here seen as ‘instruments and effects’ of discourse’ and therefore power. This approach takes a Foucauldian understanding of ‘language and concomitantly power relations which assumes that these are manifest[ed] in material and anthropological forms, that is, in policy objects (artefacts as we call them in the book), architectures, subjectivities and practices’ (Ball, 2015: 307). These two branches of CDA do not need to be mutually exclusive but have over the years been used together. Taylor (2004) encapsulates these two aspects of critical discourse analysis as tools to ‘explore the relationships between discursive practices (language), events, and texts, and wider social and cultural structures, relations, and processes’ (Taylor, 2004: 435). Hence, the use of CDA in policy is also instrumental when one is analysing policies and institutional structures pertaining to inclusion and inclusive strategies designed for schools. For example, it is not uncommon for such policies to fail at incorporating the voice of whom they are intended to cater for, thus retaining the discourse and the decision making in the hands of dominant groups. This is often observed through the use of CDA. Our first example case in the next section provides an example of this and proceeds to explain how it was mediated by a group of students and teachers together.

Although CDA is assumed to analyse what is written (visible discourse), it can also exert its critical nature by looking into potential silences which may be present in a policy. As established earlier, writing, and implementing policy are both in themselves political moves. Therefore, policymakers often try to choose the right words, while leaving out others, to achieve a desired goal, while simultaneously making sure that the language used does not disappoint or anger one or many stakeholders involved. This is often done using instances of silence which leave the policy open to interpretation by those implementing it. Moreover, such instances of silences can be indicative of policymakers failing to consider the experience of marginalised groups and the impact such policy could have on them.

Critical discourse analysis has been of great use when it comes to analysing policies which are established by supranational entities and ministries. Over the years such entities have become increasingly involved in determining the social role and purpose that education plays across different countries. With increasing power over education, the decisions taken by these entities have consolidated an ‘articulation and re-articulation of orders of discourse [which] is correspondingly one stake in a hegemonic struggle’ (Fairclough, 1992: 93). The latter implies that as education policy has over the years become increasingly guided by these entities, the latter have consolidated their power in determining the purpose of education. Simply put, such entities now have a great say in establishing what we, as educators, are teaching and why we need to teach it.

The latter may be briefly demonstrated through the impact that international studies such as PISA and PIRLS have had on teaching. As more countries participate in these studies, governments from countries performing below average became concerned and have borrowed policies from countries faring well with the hope of getting better scores in the next round of tests. This can certainly be said for Malta, which after its “worrying results” in such studies, saw a rapid change in its education policies to shift towards those present in Scandinavian countries such as Finland. Caruana (2020: 81) used CDA on policies to focus on this shift and noted that ‘there is no clear indication as to how the policies will affect teacher recruitment, and whether it will be necessary to have Continuing Development Programmes or re-training of teachers already in employment.’ A few years down the line, the implementation of these policies saw numerous challenges, especially for students, educators, and parents. This included increased paperwork and workload for teachers, teachers’ unions taking legal action by issuing directives to school staff, and parents not grasping the new system to help their children. Through this example, we can see how the silences pointed out by Caruana and left unaddressed by policymakers, led to a turbulent process of implementation which has greatly impacted school life in Malta (Caruana, 2020).

As Zaalouk (2011: 139) explains, through such entities, there has been a gradual shift towards managing education and defining its purpose to primarily ‘fit the capitalistic demands of the labour market.’ Policies often end up being hyper focused on fulfilling this need by devoting their attention to the production of a high-skilled future workforce. Having such a high skilled workforce is not something inherently problematic and can help individuals to flourish. However, in the process of establishing what is needed from education, such entities have had the power to narrow down what is to be considered as useful knowledge and the point of being in school. Over the years, this has continuously homogenised the purpose, and strategies for teaching this same knowledge whilst failing to recognise education as an act of liberation, humanisation, and emancipation. As the example of Malta suggests, educators have become hyper-focused on delivering the content established and limiting their space to understand and use the stories of the students in front of them as a form of education. Students are prepared to become small parts of a larger whole rather than holistically whole beings in themselves. This mostly impacts the students experiencing structural disadvantages. As Freire aptly puts it, ‘to glorify democracy and to silence the people is a farce; to discourse on humanism and then negate it is a lie’ (1970: 64).

Now that CDA has been established as a useful strategy which can be used by educators as they read policies and established curricula, we can look into how this together with other strategies can be used by educators so that they can become active contributors to the formulation of education policy. As authors of this paper, we believe that this can be exemplified through three individual case studies in which we ourselves have critically analysed policy to show how, through its practices or lack thereof, education was failing to address the needs of different structural disadvantages.

Case Studies

(i) Pedagogy of Coming Out, A Queer-Positive Policy

This pedagogy was recently designed to address the shortcoming of policies focusing on the safety and visibility of the LGBTIQ+ community in schools across the Maltese islands. Malta has in the last ten years recognised many rights pertaining to marriage equality, adoption, and also gender identity. Consequently, this has seen the country topping the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (ILGA) European index for several years. However, over the same decade, studies focusing on the experiences of the same community in school continued showing concerning results in terms of safety and visibility in Maltese schools. 61.9% of students still experienced derogatory language pertaining to the LGBTIQ+ community and 49.6% felt unsafe attending schools (Pizmony-Levy, 2019). The experiences of rainbow families have also shown instances of stigmatisation by different members of the school community (Schembri, 2020). So, what went wrong?

As many of these rights were being recognised, a framework containing several policies under the name Respect for All, was implemented in Maltese schools to mitigate various challenges experienced in schools by various disadvantaged groups (Ministry of Education and Employment, 2014). These also promised to address the learning to be and learning to live pillars of education as explained by UNESCO (2023) through the promotion of values of inclusion and respect for diversity. Applying a critical analysis of the discourse of the text, suggested that often these policies did not properly address the diverse needs of different disadvantaged groups. For example, while the first to locally recognise the LGBTIQ+ community as a group likely to experience bullying, it failed to elaborate on how this is to be proactively addressed by schools. Moreover, this silence on the matter was further exacerbated when the Minister for Education refused to include books containing LGBTIQ+ narratives in schools and ensuring the public that these will be kept at the ministry (Times of Malta, 2015). Therefore, these policies, as also shown by the data in the following years, failed to address the needs of specific disadvantaged groups such as the LGBTIQ+ community. To not cause too much of a stir over the inclusion of such topics in schools, the ministry’s policy left instances of silence which failed to properly address such instances of structural disadvantage.

Figure 3: Front Page of Pedagogy of Coming Out

A Pedagogy of Coming Out, was therefore designed together with local LGBTIQ+ students and teachers. The latter were recruited as participants to not only talk about their experiences in schools but to apply these to the design of a practical policy which can be easily implemented by schools (Grech, 2022). This was also presented to heads of schools to gather their insight on the challenges which can be met in implementing such a policy. The final document includes clear strategies for teachers and other stakeholders involved to ensure that these structural disadvantages are addressed. Moreover, the document leaves its implementation open to adaptation in order to allow schools to adopt practices which best work for their community, and to ensure continuous reflection and assessment of the policies’ implementation. This work was also then presented to various governmental and non-governmental organisations in Malta at a symposium.

Therefore, from this first example mentioned here, we can note how educators and students have become active agents in policy development and implementation to address structural disadvantages pertaining to the LGBTIQ+ community in schools. Using CDA, gathering insight and other experiences of educators and students, organising oneself and presenting the work to local entities, educators have designed a practical document which addresses these needs locally. However, analysis and critique of policymaking and implementation do not only need to take place in an academic arena. As educators and implementors of policies in schools, we must ensure that there is clear, bilateral, and continuous communication between those establishing policies and teachers delivering them.

(ii) Inclusion of Migrant Children through Curricula.

In response to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, numerous European nations have initiated policies aimed at integrating migrant children into their school curricula. Among these, the approach adopted by Ireland offers a noteworthy example.

The Irish Department of Education has issued guidelines to schools, advocating for the needs of the child to be central in decisions related to curriculum provision, programme access, and support. These decisions are also intended to incorporate students’ current and future needs, including their readiness for key transition stages in the Irish education system (DoE, 2022).

To facilitate this, the department has provided schools with information about the Ukrainian education system, aiming to help them recognise and validate the prior learning and educational experiences of these children. However, the practical implementation of this recognition and its impact on the students’ integration and progression in learning are yet to be determined.

For primary schools, the aims of this policy effort are to place the student in a class that best suits their age, with staff using observations and insights from the students and their families to determine the best way to meet the student’s immediate and emerging needs. For instance, in post-primary schools, the student should ideally be placed in a year group that aligns with their age, with engagement from the students and their parents to ascertain the student’s educational experience to date.

The role of teachers in this process is crucial. They are on the front lines of implementing these policies and are responsible for creating an inclusive and supportive learning environment for these migrant children. However, the effectiveness of these policies largely depends on the resources, training, and support provided to these teachers, which is an area that needs further exploration and evaluation.

(iii) Intersectionality at play: Is it possible for policy to be fully inclusive?

Absolutely not. It will be an extremely utopian expectation for one policy to be completely inclusive and address the complexity of intersectionality and marginalisation that any given individual might be facing at a given time. However, what we are trying to do here is attempt to include as many as possible and create a respectful methodology that is flexible enough to address the multiple identities, difficulties, and discussions, as they come. I would like to bring in the example of a 22-year-old social media influencer Gabe who was born in Brazil and has a severe form of Hanhart syndrome, a rare condition that caused her to be born without legs or arms, and was put up for adoption at 9 months old. She recently came out as transgender and was adopted by a family in Utah. She now has over 180,000 followers on Instagram and about 4 million followers on TikTok where she shares makeup tutorials, beauty challenges and ‘Get Ready With Me’ videos, along with offering her followers glimpses of her day-to-day life without limbs with a big smile on her face. She claims that her life changed when she came out as gay at 19 years of age to her parents. She also told her parents that she wasn’t going to change and if they wanted to be in her life, they would have to accept her as she is-and they did. This really motivated her to continue being herself with confidence and pursue her career as a beauty blogger (Hopkins, 2023).

She credits her adoptive family’s unconditional love and support for helping shape her into a confident, independent and capable person. She also thanks her school and her teachers for helping her shape her personality and pushing her towards achieving her dreams. This gave her the confidence to work as a motivational speaker, after finishing school and then touring schools and businesses to try and make a difference in her community (Hopkins, 2023). Her successful business, confident personality, and zeal to help others like herself is based on the support she received from both her adoptive parents and her educational institution. Moreover, she also would not have been able to develop a healthy emotional and mental personality if she was not motivated by her teachers and her peers. This is exactly what an inclusive education policy should do. By providing a safe flexible space for teacher agency and identifying the distinct needs of its students, it should have the capacity to nurture the true talents and persona of its students.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided an exploration of inclusive education, its significance and the unabating challenges it faces. It has underscored the role of teachers as active agents in implementing inclusive policies and the need for their involvement in the policymaking process. The chapter has also highlighted the structural disadvantages that certain groups of students face within the educational system, emphasising the need for a more equitable approach to education.

The chapter, through the case study of Malala Yousafzai and her father, underscores the transformative power of inclusive education and its potential to overcome societal barriers and promote equality, while also acknowledging the complexities and challenges that arise, particularly in contexts where social divisions and inequalities are deeply entrenched. It highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of educational policies and their impact on the everyday realities of teachers and students, advocating for a balanced approach in the development and implementation of these policies to ensure they are not only effective but also equitable.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

Finally, we would like to conclude the chapter by leaving the reader with questions for reflection as the issues discussed in this chapter certainly do not provide comprehensive answers to all the related questions. Furthermore, it’s important to note that the issues highlighted will present themselves differently in each teacher’s unique context:

- Reflecting on your current teacher training and knowledge base, in what ways do you feel prepared to enact inclusive teaching strategies in your classroom?

- Considering the structural disadvantages that your students in your classroom might face, what policies and services in your local context can help you to address these challenges?

- How do you plan to address the effects of structural disadvantages in your classroom to ensure an equitable learning environment for all students?