Section 3: Creating Inclusive Learning Environments and Participation

Self-Determination in Learning

Karen Buttigieg; Zeynep Karaosman; and Ludovica Rizzo

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Riverside Primary School prides itself on its long-standing teaching traditions, emphasising discipline and good grades in the national standardised exams. Isaac is an eight-year old student at Riverside, who is on the autism spectrum[1]. He is a bright and curious child, full of potential. However, his unique abilities are not recognised or nurtured. The classroom is filled with rows of desks, and the teacher stands at the front, while students listen passively. For Isaac, this rigid structure poses numerous challenges, including issues with his need for movement. The lack of opportunities for independent decision-making leaves him feeling frustrated and disengaged. He desires to explore his unique interests, but the curriculum offers little flexibility or choice. Isaac’s love for dinosaurs, for instance, is never acknowledged or incorporated into his learning experience. Such frustration is often translated into behaviour that is often labelled as problematic and disruptive.“

If you put yourself in Isaac’s shoes how does this affect the way you feel about school and how it is preparing you for your future?

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is self-determination in learning?

- What are the three basic psychological needs that support self-determination in learning?

- How can educators promote self-determination in their students?

- How can educators facilitate more autonomous forms of motivation at schools?

- What are the effects of rewards, feedback and other external events on intrinsic motivation?

- How can we use rewards to support students` autonomy rather than undermining it?

- Why is it important to provide our students the opportunity to make choices that enable them to partially determine their learning path?

- What teaching and learning methods (or strategies) are best able to nurture the autonomy, competence and relatedness needs of a wide spectrum of human differences?

- How can the conditions placed within the context enhance or hinder the self-determination process of our students? And how can they affect their well-being?

Introduction to Topic

Wehmeyer (1992) proposed that self-determination revolves around “the attitudes and abilities required to act as the primary causal agent in one’s life and to make choices regarding one’s actions free from undue external influence or interference” (p. 305). Exercising autonomy in decision-making is an important aspect of typical human development, fostering mutual benefits for both the individual and society at large. Ryan and Deci’s (2017) Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that individuals possess an inherent inclination for personal development, the establishment of connections within their communities, making meaningful contributions to these communities, as well as overcoming obstacles within their surroundings.

Self-determination in learning regards learning as a personal journey for each individual. It recognises the learner as an active participant in their own learning process, driven by intrinsic motivation to actively engage in the learning experience. When self-determination is present, learners have the autonomy and capability to make choices regarding their learning and set their own learning objectives. They take initiative in acquiring the new knowledge and skills necessary to achieve their goals, and they possess the ability to self-assess their progress in relation to their set objectives.

In essence, self-determination in learning entails an individual’s capacity to control and regulate their own learning process. This involves taking ownership of their learning goals, making informed decisions about learning strategies, and persevering in the face of challenges that may arise along the way. By embracing self-determination, learners become active agents in their own educational journeys, empowering themselves to shape their learning experiences and ultimately achieve their desired outcomes.

According to SDT, there are three basic psychological needs that support self-determination in learning and facilitate growth and include; autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These needs are termed basic because they are universal to human nature and transcend all cultures, age groups, and abilities.

The Three Basic Psychological Needs for Self-Determination

The need for autonomy

Autonomy as defined in SDT refers to voluntary behaviours, and the need for control and choice in the actions and decisions that individuals take in their lives, including the ability to take direct action in one’s learning process (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Of the three basic psychological needs, the concept of autonomy is often the one that is most easily misinterpreted. It is important to clarify that autonomy does not imply a need to act independently and not rely on others for assistance or guidance. On the contrary, it emphasises the ability to willingly and autonomously seek help from others and engage in collaborative efforts (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

It is also important to acknowledge that being autonomous does not imply an absence of demands or rules. Rather, autonomy involves adhering to rules when they are personally endorsed and congruent with one’s values and beliefs (Deci & Ryan, 2000). For example, in the context of physical education classes, students willingly wear training shoes because they understand the meaningful explanation behind the requirement – training shoes help to prevent injuries during sports activities.

Lastly, SDT argues that simply removing external constraints does not automatically grant individuals autonomy. In classroom settings, merely eliminating constraints without providing students with meaningful goals or missions would result in chaos. Therefore, being autonomous in SDT is about the legitimacy of the rules and the restraints as well as the internalisation of the values involved.

The need for competence

Competence refers to the need for mastery and achievement in learning tasks (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Humans are driven by a fundamental psychological need to seek effectiveness and capability in the activities that they are engaged in. However, the level of challenge presented by tasks plays a crucial role in determining one’s sense of competence. When tasks are overly challenging, to the point where the student feels a sense of failure right from the beginning, their perception of competence decreases (Deci & Ryan, 2000). On the other hand, students can be disinclined to complete a task if this is too easy or lacks sufficient challenge.

SDT emphasises that competence is not just about achieving a desired outcome but also about experiencing growth and progress. Therefore, the feeling of competence is enhanced when the tasks are optimally challenging for students and match their existing skills (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

The need for relatedness

Relatedness refers to the need for social connectedness and support from others (Ryan & Deci, 2017). It refers to the deep-seated desire to establish meaningful connections and relationships with others. Humans thrive on a sense of belonging, a sense of being part of something bigger, of a community. One aspect of relatedness stems from the experience of being cared for and supported by others (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In the educational context, when students perceive genuine care and concern from their teachers about their well-being and academic progress, it fosters a sense of connection and trust. Such nurturing environments make students feel valued and appreciated, leading to enhanced motivation and engagement in their learning journey (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Thus, teachers who demonstrate empathy, understanding, and responsiveness to their students’ needs create a conducive atmosphere where relatedness flourishes.

Relatedness is also fostered through opportunities for students to contribute and collaborate within a group setting. Actively engaging in group tasks allows students to benefit from the diverse perspectives and expertise of their peers, and gain mutual support, promoting a sense of shared goals and cooperation. It is important to emphasise that relatedness is not solely limited to students. The extent to which teachers experience a sense of relatedness themselves is dependent upon the quality of relationships they cultivate with their students (Klassen et al., 2012).

Key aspects

The importance of self-determination in learning

Self-determination in learning is important for all students as it empowers them to take greater responsibility and control over their educational journey, leading to increased engagement and motivation. When students are actively involved in shaping their learning experiences, they invest more effort and persist more in the face of obstacles. The skills that they develop such as goal setting, problem-solving and decision making, enable students to be more independent and active in their learning (Agran et al., 2008). A number of studies in this field have highlighted various positive outcomes of fostering self-determination in learning such as enhanced self-esteem (Deci et al., 1981), improved student well-being (Cheon et al., 2014) and better academic performance (Van Lange et al., 2012).

In educational contexts with standardised curricula and high-stakes exams, teachers often perceive efforts to cultivate self-determination as a waste of time (Parrish et al., 2024). However, investing time in promoting students’ autonomy pays off significantly. It leads to students setting more ambitious goals, demonstrating perseverance in the face of challenges, and acquiring essential self-regulation skills like time management. This increased self-directedness and autonomy in learning, results in a deeper understanding of the content, as learners start connecting new knowledge that they are acquiring at school with their prior experiences (Garrison, 1997). Thus, there is a shift in responsibility from the teacher to the learner, with regard to learning, where the teacher becomes more of a mentor who can support and guide the learner to improve academic performance.

Regrettably, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities often encounter limited opportunities for exercising personal choice and decision-making and may have limited control over the circumstances that significantly impact their day-to-day existence (Cottini, 2016; Wehmeyer, 1996). Nevertheless, various studies provide evidence of the importance of self-determination skills for such individuals. Such studies include, but are not limited to the following:

- When students with autism are provided with opportunities for choice-making, problem behaviours are reduced whilst adaptive behaviours increase (Reinhartsen et al., 2002).

- Teaching a self-regulated problem-solving process to students with severe disabilities enables them to achieve various educationally relevant goals (Palmer et al., 2004).

- Students with learning disabilities but high self-determination were twice as likely to be employed than those with low self-determination (Wehmeyer & Schwartz, 1997).

- Students with cognitive disabilities and high self-determination were significantly more likely to live independently (Wehmeyer & Palmer, 2003).

- Providing choice opportunities as an intervention to reduce problem behaviour in students, resulted in significant reductions in such behaviour (Shogren et al., 2004).

Additionally, there is a positive correlation between self-determination and IQ, but IQ is not a predictive factor of the level of self-determination that a student can reach, particularly for students with disabilities (Wehmeyer & Garner, 2003).

Teaching which promotes self-determination can also benefit teachers. Educators who engage in workshops specifically designed to enhance their skills in promoting autonomy support (compared to teachers in a control group) not only demonstrate a higher level of autonomy-supportive teaching, but also report a greater sense of satisfaction in their teaching, a stronger passion for teaching, increased teaching efficacy, and reduced emotional and physical exhaustion after teaching (Cheon et al., 2014). This reinforces how teachers can experience significant professional advantages by embracing self-determination in learning.

Motivation in Self-Determination Theory

SDT defines motivation as the driving force behind human actions and the reasons why a person engages in specific behaviours. It also suggests that motivation can take different forms, depending on the level of self-determination involved (Deci & Ryan 2008). One of these forms is intrinsic motivation which arises from a genuine interest, or alignment with one’s internal values. Conversely, extrinsic motivation represents a different type of motivation, one driven by external forces such as rewards and punishments.

When individuals with authentic or intrinsic motivation (self-authored or endorsed) are compared to those who are merely externally controlled, the former typically display more interest, excitement, and confidence. These qualities in turn manifest both as enhanced performance, persistence, and creativity (Deci & Ryan, 1991; Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne & Ilardi, 1997), as well as heightened vitality (Nix, Ryan, Manly & Deci, 1999), self-esteem (Deci & Ryan, 1995), and overall well-being (Ryan, Deci & Grolnick, 1995). Remarkably, these positive effects persist even when individuals have the same level of perceived competence or self-efficacy for the particular activity (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

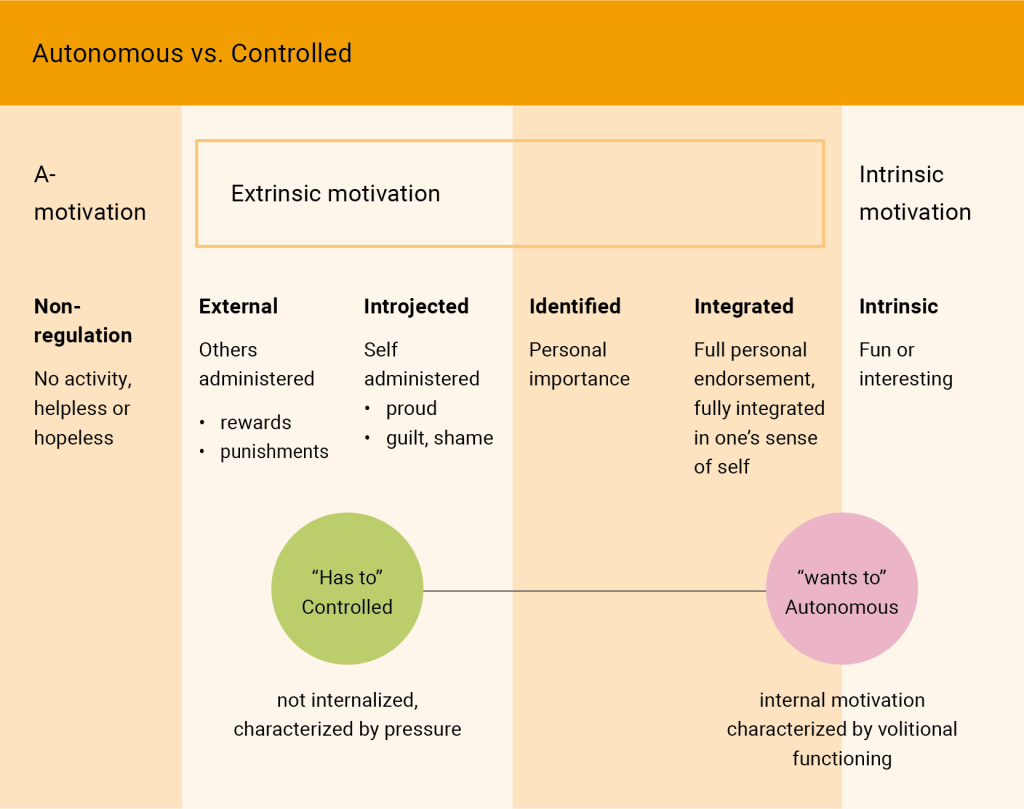

In SDT, intrinsic motivation represents the most self-determined form of motivation. When an activity is intrinsically motivating, students engage in it willingly, driven by genuine interest and enjoyment, rather than engaging to receive some external reward or avoid punishment. While intrinsic and extrinsic motivation might seem diametrically opposed, there is another important distinction within these types of motivation. SDT differentiates, therefore, between autonomous and controlled motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

Autonomous motivation stems from internal sources and can be subdivided into identified, integrated and intrinsic motivation. In this case, individuals are driven by a sense of personal relevance or integration of the activity with their core values and identity. On the other hand, controlled motivation, which can be subdivided into external and introjected motivation, is derived from feelings of pressure either from within oneself or the external environment. In controlled motivation, individuals engage in actions not because they genuinely want to, but because they feel obliged or coerced.

Figure 1: Autonomous vs. Controlled

Figure 1 illustrates the taxonomy of different forms of motivation in SDT. Ryan and Deci (2008) created the Self-Determination Continuum by dividing motivation into six categories of regulatory styles – from the least motivational to the most motivational. At the far left of the self-determination continuum is A-motivation which means not having the intention to act. According to SDT, a-motivation results from not valuing an activity (Ryan, 1995), not feeling competent to do it (Bandura, 1986), or not expecting it to yield a desired outcome (Seligman, 1975). In a learning environment, therefore, we can assume that our students would be a-motivated to engage in an activity or a task when they are not convinced of the outcome of the activity/task or when it is too hard for them to achieve it.

Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, covers the continuum between a-motivation and intrinsic motivation, varying in autonomous level. External regulation refers to the least autonomous form of extrinsic motivation and includes behaviours performed to meet and satisfy an external demand. A typical example would be a student who does their homework regularly to avoid punishment or studies hard to get good grades to get rewarded by their parents. Although the behaviour is intentional, it is still controlled and regulated by an external source. A second type of extrinsic motivation is introjected regulation which refers to taking in the cause of the action but not fully accepting it. This involves behaviours that are performed to avoid guilt and anxiety or to get recognition from others and maintain feelings of worth. A student who spends lots of time working on their classroom presentation in order to feel more respected, or avoid the risk of being laughed at by their classmates, could be an example of introjected motivation. Although it includes relative self-control and it is internally driven, introjected regulation is still considered as controlled by external sources and therefore is not autonomous. Thus, in some studies, external regulation (being interpersonally controlled) and introjected regulation (being intrapersonally controlled) have been combined to form a controlled motivation composite (e.g., Williams, Grow, Freedman, Ryan & Deci, 1996) (as cited in Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Identified regulation refers to the more autonomous and less controlling form of extrinsic motivation. Identification means when the person performs a behaviour because they consciously and personally value the goal of the action rather than doing it because they feel obliged to. For instance, a student studies hard for the SAT exam because gaining access to college is important to this student. In this example, gaining access to college is a personal and self-selected goal and is therefore relatively autonomous although the behaviour is extrinsically motivated. Alternatively, this differs to the student believing that their parents would be disappointed by not getting into a college (i.e., introjected regulation) or as a personal choice if their parents were pressuring them (i.e., external regulation). The most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation, which refers to the congruence of behaviour with one’s own values and needs. In other words, it is a form of motivation when a person has fully embraced the reason for action after examining the cause and necessity of it. While the behaviour is not performed because it is interesting or fun, integrated regulation is valued and experienced as autonomously motivating.

Lastly, at the far right of the continuum, intrinsic motivation is the act of doing something out of interest and is therefore considered to be highly autonomous. In some studies, identified, integrated, and intrinsic forms of regulation have been combined to form an autonomous motivation composite (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Ryan and Connell (1989) tested the formulation that these different types of motivation, with their distinct properties, lie along a continuum of relative autonomy. They investigated achievement behaviours among school children and found that external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic regulatory styles were intercorrelated according to a quasi-simplex pattern, thus providing evidence for an underlying continuum. Furthermore, differences in the type of extrinsic motivation were associated with different experiences and outcomes. For example, the more students were externally regulated, the less they showed interest, value, and effort towards achievement and the more they tended to disown responsibility for negative outcomes, by blaming others such as the teacher. Introjected regulation was positively related to expending more effort, but it was also related to feeling more anxiety and coping more poorly with failures. In contrast, identified regulation was associated with more interest and enjoyment of school and with more positive coping styles, as well as with expending more effort (as cited in Ryan & Deci, 2000).

The attitudes and skills needed for self-determination in learning

Mithaug and colleagues (1998) describe self-determination as a set of abilities that empower individuals to:

- know and express their interests, needs and abilities;

- set their own expectations and goals in order to meet these interests and needs;

- make choices, decisions and plans;

- act to realise their projects;

- evaluate the consequences of their actions;

- modify their actions and plans in order to achieve their desired goals.

The cultivation of self-determined behaviour relies on personal skills – such as the capacity to make informed choices, set goals, and self-monitor one’s actions. Additionally, the environment plays a crucial role in facilitating the implementation of these behaviours (Cottini, 2016). Therefore, a lack of self-determination may result from inadequate capacities to perform self-determination skills, either from inappropriate opportunities to develop, acquire or employ these skills, or both (Mithaug et al. 1998). This implies the need to address the causes of low levels of self-determination, attaining to define appropriate interventions to improve them. Taking this into account, the development of skills and attitudes for self-determination begins before children enter the school system and continues into adulthood (Sands & Doll, 1996), and it is essential to foster and enhance this process by creating a supportive school context.

To nurture self-determination, schools must devote attention and effort to the development of intrapersonal, metacognitive and social skills among students. By doing so, students can gain a deep mastery of these skills, ensuring that they have the tools to shape their own paths successfully. This investment in students’ self-determination skills will empower them to make meaningful choices, set purposeful goals and take charge of their own educational journey, and ultimately, their lives beyond the classroom.

Intrapersonal Skills

Intrapersonal skills play an important role in fostering and enhancing the self-determination of every student. In order to make informed and responsible decisions, and to navigate a self-directed learning journey, it is essential to develop a deeper understanding of oneself. This understanding encompasses knowing your true aspirations, identifying meaningful goals, recognising the strategies and resources at your disposal, and mastering the art of using them effectively. Self-awareness and self-management become the compass that guides students in building a harmonious relationship with the environment, and in turn, unlocks the full potential within each individual (Rose, 2016).

Accepting and valuing the self

Accepting and valuing the self is one of the basic components that provide a foundation for acting in a self-determined way. It involves acquiring awareness of one’s internal states, preferences and resources, and recognising their value on a personal and community level. It is not limited to “I see myself and I like what I see”, but also encompasses the feeling of possessing a “unique worth”. Students’ experiences in school have a strong impact on the image they possess of themselves, and the significance they attach to different aspects of themselves. Effective methods to foster self-acceptance may include discussing with pupils the meaning of the term, providing examples of how self-accepting self-talk can be applied in difficult situations, and designing activities that enable students to become more aware and appreciative of their own positive qualities (Bernard et al., 2013).

Awareness of personal learning strengths, weaknesses, preferences and needs

Evaluation of the self is another important competence that enables self-directed learning (Patterson et al., 2002). Students who develop self-awareness recognise their strengths and weaknesses, and use this understanding to effectively shape and direct their own learning journey, making informed choices. Students acquire this knowledge by interacting with the school environment (Jonassen and Land, 2012), therefore it is essential to provide them with the opportunity to discover different aspects of themselves, to explore several ways of learning and fields of interest, and to develop the ability to proactively act accordingly. It is essential to enable them to communicate their preferences and prioritise their needs, whilst also evaluating their current status in relation to learning goals.

Knowing options, supports and expectations

Individuals differ in the extent to which they act according to personal beliefs, values, interests and abilities (McClelland, 1985). The degree to which learners act in behaviours that align with the perceived self depends on several factors. In addition to acquiring self-awareness, it is necessary to develop the abilities to read the context and identify available choices and opportunities for personal growth, as well as difficulties that may be encountered and sources from which one may seek support in times of uncertainty (Snowden, 2002).

Teachers, in addition to peers, play an important role in fostering resilience, supporting students on social and emotional issues for learning, helping them proactively manage the discomfort inherent in risky tasks, being reflective and moving forward in self-determined learning.

Knowing what is important on a personal level

Since self-determination is also defined as the process through which individuals manage and direct their lives towards meaningful goals for their existence, being aware of what is important on a personal level is one of the preliminary steps that enable them to pursue these goals (Deci & Ryan, 2012). This knowledge derives from an acquired deep awareness of one’s potential, resources and aspirations – ascribed to a personal level – and from an analysis of the interaction with contextual factors, which can decline further paths of development based on how they hinder or facilitate the pursuing of the person’s intentions and needs.

Risk-taking

Being willing to take risks plays an essential role in theories of motivation, and is a fundamental competence for actualising the process of self-determination. Risk-taking can be defined as engaging in adaptive learning behaviours (sharing tentative ideas, asking questions, trying to do and learn new things) that put the learner at risk of making mistakes or appearing less competent than others (Beghetto, 2009). Learning, like other areas of life, involves uncertainty and, therefore, a degree of risk (Byrnes, 1998). Students are often reluctant to jump into the learning process because they fear failure, a bad grade, negative teacher judgement, or devaluation by peers.

In a school system based on the one-size-fits-all approach, students generally tend to converge on one right way to complete a task or master a skill, thereby reducing overall achievement (Magableh & Abdullah, 2020). However, taking risks and accepting challenges, especially when these arise from personal inclinations and aspirations, motivates the student to not only engage more in the learning process, but also to perform better. A continuous recalibration of learning goals is necessary to overcome any knowledge gaps, acquire new thinking tools, define what is important to the individual, and develop metacognitive skills that will also serve well to self-direct one’s own education (Bembenutty et al., 2013).

Persistence

One of the competencies closely related to self-determination is perseverance, defined as the ability to maintain commitment to a goal despite challenges. This skill represents a fundamental component in the development of adequate resources aimed at ensuring the achievement of long-term educational and formative goals.

Like resilience, perseverance depends on both internal and external resources and emerges through a dynamic interaction between the individual and their environment (Malaguti, 2016; Swanson et al., 2013). Consequently, analysing environmental contexts is crucial to identifying and addressing factors that can either foster or hinder the development of this skill. This reflection is particularly significant within the framework of self-determination. Contexts that satisfy the three basic psychological needs proposed by the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) — autonomy, competence, and relatedness — exert a substantial positive influence on perseverance (Vansteenkiste et al., 2004).

The pursuit of intrinsic rather than extrinsic goals in learning facilitates a deeper understanding of content, stronger concept acquisition, and greater long-term persistence (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). Conversely, the introduction of rewards for activities that are already intrinsically motivating, such as the use of controlling language, or the presence of external factors such as rigid deadlines or surveillance, can undermine the need for autonomy, leading to reduced persistence and enjoyment of the activity (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006).

Self-determination and perseverance are deeply interconnected. When students are empowered to act in alignment with their authentic selves, pursue their own interests, values, and goals, and feel competent, they are more likely to overcome academic challenges and exhibit greater perseverance in achieving their objectives.

Emotional control

Emotional control and self-determination are also closely interconnected. Firstly, emotional control represents an essential metacognitive skill that plays a crucial role in the self-determination process. The ability to manage one’s emotions and regulate behavior allows students to effectively channel the available resources towards achieving their set goals.

In parallel, self-determination enables an autonomous path of emotional self-regulation, particularly when individuals freely choose goals that align with their personal values. Unlike controlled situations, this approach enhances positive outcomes, including personal growth, the fulfillment of psychological needs, well-being, healthy relationships, and prosocial behaviours (Benita, 2020). Moreover, providing students with opportunities for choice enhances dopamine release, which not only encourages positive emotional responses but also boosts focus, memory, and motivation (Sousa, 2010).

Planning and metacognition

One crucial aspect of self-determination is effective planning and metacognition, which involves setting educational goals based on personal interests, abilities, and needs, as well as effectively monitoring progress. This section explores the key abilities and skills needed for successful planning and metacognition in the pursuit of self-determination.

Setting and modifying educational goals

To begin the process of setting educational goals, individuals need to embark on a two-step journey. Firstly, it is essential to engage in self-reflection, recognising personal interests, passions, strengths and talents as outlined in the previous section. This self-reflection helps in identifying specific educational needs and areas for growth (Travers, et al., 2015). Secondly, armed with this self-awareness, individuals can translate their interests, abilities, and needs into concrete and achievable educational goals. These goals should be measurable, realistic, and aligned with long-term aspirations. By following this process, individuals can effectively set educational goals that are meaningful and conducive to their personal development. Moreover, individuals need to eventually be able to demonstrate dedication and ownership towards their chosen educational goals, understanding the importance of personal investment in goal attainment. Cultivating a sense of responsibility for one’s own learning journey further empowers individuals to take control of their education and shape their own educational path (Baxter, 2007).

Flexibility in goal setting is also an important aspect of self-determination. Individuals must recognise that goals need to be reassessed as circumstances change. Personal growth, shifting interests and unforeseen challenges may necessitate the modification or refinement of goals to align with the new reality. Seeking feedback from mentors or educators can provide valuable guidance in the process of goal modification, ensuring that adjustments are made in a strategic and informed manner. Embracing flexibility in goal setting, allows individuals to adapt to evolving circumstances and maintain relevance in their pursuits (Wrosch, et al., 2003).

Breaking down goals into small steps, tracking progress and modifying action plans

Breaking down goals into manageable small steps is a fundamental strategy for achieving self-determination. This approach helps individuals avoid feeling overwhelmed and enables them to maintain focus on making consistent progress. Prioritising tasks and setting timelines for completion further aids in effective goal management. Utilising tools such as to-do lists, planners, or digital apps provides a structured approach to organise and track progress, fostering a sense of accomplishment and motivation throughout the journey.

Engaging in self-reflection, self-assessment and tracking progress are important for pursuing self-determination as it allows for identification of areas for improvement and the necessary adjustments to strategies and actions (Loman, et al., 2010). Additionally, celebrating achievements along the way serves as positive reinforcement, fuelling motivation to continue striving towards set goals (Geller, 2016). Identifying areas for further growth empowers individuals to set new goals and continuously challenge themselves. Proactively revising action plans in response to unexpected deviations ensures that learners maintain focus, stay motivated, and confidently navigate through challenges, ultimately propelling them closer to their goals and fostering self-determination.

Active participation in decision-making and accessing resources and support

Active involvement in decision-making related to educational goals and advocating for personal preferences and needs is a fundamental aspect of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 2012). Identifying and accessing resources such as textbooks and online materials to enhance the learning experience is equally crucial for fostering self-determination. Moreover, seeking guidance and support from teachers, mentors, family members or peers becomes essential when facing important decisions or challenges. Developing effective communication skills plays a vital role in expressing needs and seeking assistance effectively. By actively engaging with resources and seeking support, individuals can maximise their opportunities for learning, growth and success (Barron, 2006).

Knowledge and adaptation of learning strategies

Possessing knowledge of various learning strategies not only enhances understanding and retention of information, but is also a key driver of self-determination. This is due to the ability to make use of different strategies based on the specific task at hand and allows individuals to optimise their approach for better learning outcomes (Schmeck, 2013). Reflecting on the effectiveness of these strategies and being open to making adjustments when necessary fosters continuous improvement and skill development. By possessing a repertoire of learning strategies and actively evaluating their efficacy, individuals can become more efficient and effective learners (Hattie & Donoghue, 2016).

Willingness to attempt challenging tasks

The willingness to attempt challenging tasks involves embracing a growth mindset by recognising that taking on difficult tasks can lead to personal and skill development (Dweck, et al., 2014). Such a mindset allows the learner to adopt a positive attitude towards learning and overcome the fear of failure. By stepping out of their comfort zones and pushing their boundaries, individuals cultivate resilience, perseverance, and a sense of achievement. This willingness to embrace challenges ultimately empowers them to expand their capabilities and enhance their self-determination (Ryan & Niemiec, 2009).

Interpersonal skills

Interpersonal skills are ways of interacting with others which make it easier to communicate effectively, both verbally and non-verbally. Interpersonal skills are essential for self-determination. They help learners cooperate and work with other learners while engaging in goal-directed and autonomous behaviour (McCornack, 2019). These skills include but are not limited to:

- Establishing and maintaining relationships with others involves building connections with peers, teachers, and others in the learning environment. It requires effective communication, active listening, empathy, and understanding of different perspectives.

- Seeking or offering support and help when necessary involves recognising when assistance is needed and being willing to seek or offer help. It fosters a culture of support and collaboration.

- Conveying information and expressing oneself clearly and effectively involves communicating thoughts, ideas, and information clearly and concisely by using appropriate language, tone, and non-verbal cues.

- Working collaboratively with other learners toward a common goal involves effectively working as part of a team, contributing ideas, listening to others, and collaborating towards a shared objective.

- Being able to negotiate to reach an agreement or compromise with others involves engaging in constructive dialogue and negotiation to find common ground and reach agreements or compromises.

- Actively listening to others and understanding their perspectives involves giving full attention to others, focusing on understanding their message, and demonstrating empathy.

- Resolving conflicts constructively involves addressing conflicts or disagreements in a positive and constructive manner. It includes active listening, empathy, and finding mutually agreeable solutions.

- Identifying social cues (both verbal and nonverbal) to understand how others feel involves recognising and interpreting social cues to understand others’ emotions. It requires empathy and sensitivity.

- Demonstrating empathy and compassion involves understanding and sharing the feelings of others, and showing care and support.

Promotion of self-determination in learning in the classroom

Teachers, as the primary adults who interact with learners in school settings, play a significant role in fostering self-determined motivation. Teachers who support autonomy can foster self-determined motivation in their students (Reeve, 2006). This conclusion has been reached across various educational levels, including primary school (Ryan & Grolnick, 1986), high school (Trouilloud et al., 2006), and university (Williams & Deci, 1996). This equally applies to students with severe behavioural problems (Savard et al., 2013). Regardless of the level of education or the difficulties students encounter, teachers adopting an autonomy-supportive teaching style significantly contribute to cultivating greater self-determined motivation in their students. Furthermore, these benefits appear to be consistent across cultures, as similar findings have been observed in non-Western cultures such as Russia (Chirkov & Ryan, 2001) and China (Hardré et al., 2006).

Educators can promote self-determination in their students by fostering an environment that supports autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This can be achieved through various strategies as will be shown in the following subsections. These include, but are not limited to, offering choices and flexibility in learning tasks, providing opportunities for students to engage in self-reflection and goal-setting, and creating a supportive and collaborative learning community. Additionally, educators can also provide feedback and praise that supports students’ sense of competence and progress towards their learning goals. All of this requires the provision of space and time for the teacher to engage in continuous self-reflection.

Wehmeyer et al. (2012) provided evidence that using the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction over two years significantly improved the self-determination of high school students with cognitive disabilities when compared to a one-year intervention. This highlights the importance of more sustained efforts to promote self-determination as opposed to time-limited interventions.

Autonomy

Autonomy refers to the need to feel that one is acting out of a sense of volition and self-endorsement (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). As we have discussed above, autonomy in SDT does not mean that there are no rules, constraints or requirements for students in their learning environment. Chaos will be inevitable in such a classroom setting where all the constraints and rules are taken away. Students need legitimate commands and restraints that they can internalise. Involving our students in the process and allowing them to take ownership of their learning environment can be a way to create a set of rules that students will autonomously and willingly follow.

SDT argues that the way teachers engage with their students (autonomy-supportive vs. controlling) is one of the most decisive factors affecting the classroom climate. In classrooms, where autonomy is supported, teachers provide students with opportunities, choices and options to encourage them to take initiative and responsibility for directing aspects of their own learning. It is important to underline that these opportunities should align with, and be relevant to, students´ needs, interests and assignments. On the other hand, controlling teachers tend to monopolise learning materials, and pressure students to think and behave in a particular way without considering the needs of the students (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, & Ryan, 1991).

Table 1:Teacher Behaviours Shown Empirically to Be Autonomy-Supportive, and Those Shown to Be Controlling

| Teacher behaviors that promote autonomous motivation | Teacher behaviors that promote controlled motivation |

|---|---|

|

|

Based on Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006) Self Determination Theory, Basic Psychological Needs, in Motivation, Development, and Wellness (Ryan & Deci, 2017)

According to SDT, students with disabilities have the same basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness) as all other students. Therefore, teacher involvement in learning or behaviour change, although it might be well intended, must respect and foster students’ autonomy. Focusing merely on the outcome and putting on more pressure can be especially strong when it comes to students with disabilities. This can lead to a risk of disengagement. Instead, promoting autonomy and self-determination rather than training and management based on external control, ultimately brings more adaptive developmental outcomes.

It is also important to mention that when teachers are autonomy-supportive, they understand students’ needs and perspectives. In this way, teachers can realise when their students need relational and competence support. Therefore, autonomy-supportive teachers typically support the other two basic psychological needs.

Providing choice

To effectively instil choice-making skills, it is necessary to integrate systematic and structured opportunities for students to select options that align with their individual preferences in their daily routines (Lohrmann-O’Rourke & Gomez, 2001).

Lohrmann-O’Rourke and Browder (1998) provided recommendations for conducting preference assessments for students with disabilities, which include the following elements:

- Offering repeated opportunities for students to make choices.

- Conducting trial assessments in the actual environment where the choices are available, combined with careful observation of the students.

- Administering repeated assessments over multiple days to gauge consistency in preferences.

- Periodically assessing preferences over time to capture any potential changes.

- Presenting choice stimuli in a format that students can easily understand, such as using pictures or actual items.

- Allowing students to directly select their choices by touching, picking up, or pointing to the desired option.

- Presenting choices in a paired format, limiting the options available for selection.

In their article on choice-making, Shevin and Klein (1984) emphasised the importance of integrating choice-making opportunities throughout the school day. They identified five key factors for maintaining a balance between student choice and professional responsibility:

- Integrating student choices as an initial step in the instructional process.

- Increasing the number of decisions the student can make within a given activity.

- Expanding the range of domains in which students can make decisions.

- Increasing the significance of the choices made by students in terms of risk and long-term consequences.

- Maintaining clear communication with students about areas where choices can be made and the boundaries within which those choices can be exercised.

According to Kohn (1993), schools have the potential to offer students meaningful choices in academic areas, such as involving them in decisions regarding what, how, and why they learn. Although offering students choices in learning demands additional commitment and effort from teachers, it is justifiable to do so, such as allowing students to work individually, in small groups, or as a whole class, and providing alternatives for seating arrangements during their work (Kohn, 1993).

Using appropriate language and demonstrating patience

The language used to promote autonomous choice-making should be informative, non-pressuring, and supportive. Threats, rewards, or punishment should not be used to motivate self-determining behaviour.

Demonstrating patience is a vital aspect of fostering student autonomy. It involves maintaining a calm demeanour while waiting for students’ input, initiative, and willingness to participate in learning activities. Patience allows students the necessary time and freedom to overcome any initial barriers, explore and manipulate learning materials, ask questions, retrieve information, set goals, evaluate feedback, formulate and test hypotheses, monitor and revise their work, recognise the need to start afresh, adjust problem-solving strategies, revise their thinking, monitor progress, pursue their own direction, reflect on their learning and progress, and work at their own pace and natural rhythm (Reeve, 2016).

It is understandable why teachers may find it challenging to maintain patience due to factors such as time limitations and high-stakes testing. However, the importance of patience from a motivational standpoint stems from a genuine appreciation for student autonomy and an acknowledgement that cognitive engagement and learning processes require time to unfold effectively.

Providing rationales for tasks

Engaging students in a dialogue about the purpose of their learning and the rationales behind certain tasks is often overlooked when implementing choice in the classroom. Simply telling students that they must learn something for their own benefit or for reasons centred around the teacher is likely to restrict student self-determination. According to Deci and Chandler (1986), offering learners a rationale for their activities enhances motivation and engagement.

Responding to students’ needs and interests

It may seem evident, but it is often observed that teachers deliver the curriculum content in a way that lacks stimulation and thus fails to nurture children’s innate curiosity. This includes an overreliance on rote learning instead of engaging in enriching educational tasks. Consequently, teachers are encouraged to design educational activities that are authentic and meaningful to children, fostering their natural desire to learn. It thus becomes important to inquire more about students’ interests and preferences.

Considering the students’ perspective is crucial for self-determination in learning. By engaging in perspective-taking, teachers develop increased empathy and a deeper understanding of students’ motivational strengths, leading to classroom environments where students’ internal motivations guide their engagement. When lesson planning overlooks students’ perspectives, educational outcomes become less optimal.

Teachers can start lessons with a conversation that fosters perspective-taking, demonstrating openness and a genuine willingness to invite, seek, and incorporate students’ input and suggestions into the lesson plan and its execution. Naturally, the teacher’s responsiveness to students’ input and suggestions is crucial. Therefore, the teacher should be prepared to integrate their ideas, provided they align with the learning objectives.

Fostering curiosity and intrinsic motivation

Curiosity emerges when students encounter an unexpected gap in their knowledge (Silvia, 2008). It is fulfilled when students engage in exploratory behaviour to acquire the necessary information to bridge that knowledge gap. This process of exploration, often referred to as engagement, leads to knowledge expansion, learning, and increased expertise. In the classroom, teachers can nurture students’ curiosity through various approaches, such as posing thought-provoking questions, creating suspense regarding upcoming content (Abuhamdeh et al., 2015), and encouraging students to explore new activities (Proyer et al., 2013). In addition, teachers can foster students’ intrinsic motivation by presenting the learning activity as a chance for personal growth, skill enhancement, building closer relationships with others, or making constructive contributions to their community (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006).

Dealing with barriers and negative emotions

It is important for teachers to be attentive when they sense something is amiss with a student, keeping an eye out for the various internal and external barriers to motivation. When negative feelings arise, they should be acknowledged, and when the right moment arises, teachers should enquire about the student’s experiences in a supportive and non-judgmental manner so that the student does not feel defensive. By actively listening, teachers can gain a deep understanding of the challenges the student may be facing and more effective collaboration.

While the significance of learning and organisational skills is widely recognised, teachers often overlook the potential impact of emotion-management skills. Failures, particularly those perceived as unjust, often trigger intense emotions such as anger, envy, sadness, or anxiety. In their attempt to cope with these emotions, students may employ strategies that provide temporary relief but are detrimental in the long run, such as devaluing the importance of the subject they failed in, denying the failure and its implications, unjustly blaming others for their failure, or disregard helpful feedback from teachers (Skinner & Wellborn, 1997).

In such situations, teachers can help students develop more constructive coping strategies by drawing from cognitive-behavioural approaches like acceptance and commitment and mindfulness training (Greenberg & Harris, 2012). These approaches can help students cultivate resilience, acceptance of failure, and a mindful awareness of their emotions, leading to healthier and more productive responses to setbacks.

Addressing negative emotions in the classroom, especially anger and resentment, can be a challenging task. However, teachers who recognise and validate students’ negative emotions have a better chance of diffusing them (Reeve, 2016). This approach not only helps in achieving the immediate goal of alleviating negative emotions but also contributes to the long-term goal of establishing a stronger connection with students.

Competence

Providing appropriately challenging activities and ongoing scaffolding

Teachers can enhance students’ need for competence by presenting them with appropriate challenges to pursue within a supportive and accepting environment that allows for mistakes and failures (Keller & Bless, 2008).

Scaffolding, which refers to the support and guidance provided by teachers to help students in the learning process, is also powerful. Through clear and explicit instructions, modelling desired behaviours and skills, and gradually reducing support, teachers enable students to gain competence and confidence in independent learning. This gradual release of responsibility fosters a sense of mastery and self-efficacy.

Providing informative feedback

To further promote students’ sense of competence and autonomous motivation, it is essential to provide them with frequent informational feedback as they work towards their objectives. According to Hattie and Timperley (2007), the primary objective of feedback is to minimise the gap between students’ current performance and their expected performance. Tangible information about their current performance, coupled with guidance towards achieving their goals, can bridge this gap effectively. Research suggests that such feedback should be specific, non-comparative, focusing primarily on positive aspects, and aligned with a constructive success theory (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). It is preferable for some of this feedback to be informal and verbal, rather than formal or written, occurring naturally as the teacher moves around the classroom or briefly checks in with students (Assor, 2016).

Relatedness and Collaborative Learning

Teachers play a pivotal role in addressing students’ need for relatedness by providing them with opportunities to engage in communal social interactions. They can provide the space for learning within groups and for planning, implementing, and evaluating collective actions. In such groups, students engage in socially responsible forms of regulation as the other members of the group model various learning strategies and provide motivational support.

Peer support

Peer support is an essential aspect of creating a supportive learning environment. Teachers can teach students how to provide and receive feedback effectively, recognise appropriate moments to seek feedback, and understand how to offer feedback that supports and enhances the learning process without diminishing the recipient’s self-esteem or social status (Assor, 2016).

Relatedness between students and teacher

Establishing positive relationships between students and teachers is equally important. One effective approach is scheduling individual meetings with students, which becomes feasible during cooperative work since teachers are not required to divide their attention among other students. During these meetings, the teacher can dedicate time to discussing students’ values, needs, and interests. In this context, students feel a strong connection with their teacher because the focus is on their preferences and emotional well-being, rather than solely on their grades.

Interestingly, teachers who report higher levels of relatedness with students are more likely to experience positive outcomes, such as improved emotional well-being, compared to those whose connections are primarily with their colleagues (Klassen et al., 2012). This highlights the importance of establishing positive relationships with students and the significant impact they can have on both teachers and students. There is a chapter on Relationships in inclusive education in this book for those seeking further information on this topic.

Factors beyond teaching that influence self-determination

School curricula or materials are often not prepared to be intrinsically motivating or made to be particularly meaningful or relevant to students’ daily lives or purposes. Many educational systems and schools have become extremely focused on a very narrow set of cognitive goals that neglect students’ different interests, talents, and psychological and intellectual needs.

Student motivation is also closely linked to teacher motivation and well-being. When teachers face limited professional autonomy and pressure to achieve specific outcomes, they may resort to more controlling motivational strategies. Teachers worldwide often face considerable pressure within school systems, which can restrict their ability to foster self-determination in the classroom. When teachers themselves lack the necessary autonomy, competence, and sense of relatedness in their profession, their capacity to promote student autonomy and effective learning is diminished. Through a combination of research findings, Brenner (2022) revealed that by fulfilling teachers’ autonomy needs they are more likely to be more motivated, provide meaningful reasons for tasks, use less controlling methods in the classroom, involve students more, provide opportunities for student choice, and offer support. This highlights the significance of supporting teachers’ autonomy to encourage practices that enhance students’ self-determined motivation.

Additionally, it is also important to always keep in mind that schools are not isolated and that children come to school already with a baggage of experiences and factors that are affecting them. One key factor relates to the family and home setting. If families embrace values of self-determination, such as openness and discussion, students are more likely to be receptive to self-determination in the classroom. On the other hand, if home life and parenting are controlling, students may struggle when encountering opposing beliefs and values at school (Grolnick et al., 1997). Families also exist within the larger context of culture and society, and sometimes also microcultures. These shape their belief systems and values, particularly regarding the roles of specific groups of people. For example in many societies, children are seen as having a much lower expertise than adults, leading to their voices being perceived as less important.

Example case revisited

Riverside Primary School has undergone a remarkable transformation in its approach to education, placing a profound emphasis on fostering self-determination in learning. Among the thriving students in this new environment is eight-year-old Isaac, who is on the autism spectrum. This forward-thinking school has veered away from traditional teaching methods that focused solely on discipline and standardised exam scores.

The classroom at Riverside has been completely redesigned to promote active engagement and individualised learning. Isaac now finds himself in a vibrant and flexible learning space that accommodates his need for movement, enabling him to fully participate in classroom activities. This small but crucial adjustment has made an immense difference in Isaac’s learning experience.

One of the pivotal changes at Riverside is the integration of student autonomy and choice. Isaac is now empowered to make decisions about his learning journey, allowing him to delve deeply into his passionate interest in dinosaurs while also learning core subjects like mathematics. This autonomy has sparked a newfound enthusiasm in Isaac, and his eagerness to learn and explore is now understood and appreciated.

Previously, Isaac’s behaviour was often labelled as problematic and disruptive. However, with the shift in approach at Riverside, it has become evident that his behaviour was merely a sign of his intense curiosity and yearning for knowledge. The school now recognises and nurtures his unique abilities, celebrating his individuality rather than suppressing it.

If you put yourself in Isaac’s shoes how does this affect the way you feel about school and how it is preparing you for your future?

Conclusion

This chapter has delved into the concept of self-determination in learning, exploring the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The attitudes and skills needed for fostering autonomy and motivation in students’ learning journey have also been uncovered, whilst also acknowledging that factors beyond teaching, such as students’ home environment and cultural influences, can impact self-determination.

Self-determination in learning considers learning as a personal journey and argues that learners should take ownership of their own learning process and take initiative in shaping their learning experiences. This involves being an active participant in setting their learning goals, making informed decisions about their own learning strategies and being determined to achieve their desired outcomes despite the challenges that may occur during the learning process.

Incorporating the principles and strategies discussed in this section can lead to transformative experiences for students, igniting their intrinsic motivation and passion for learning. Empowering students to take ownership of their learning journey ultimately prepares them to navigate challenges and thrive in their educational pursuits and beyond. Isaac’s experience at Riverside Primary School, for instance, is a good example highlighting the transformative power of fostering self-determination in learning. By creating an environment that values autonomy, competence, and relatedness, Riverside has enabled Isaac to thrive and embrace his unique interests and abilities. The school’s emphasis on student choice, flexible learning spaces, and supportive relationships has empowered Isaac to take ownership of his education and shape his own learning journey. This shift in approach has not only improved Isaac’s engagement and motivation but has also challenged traditional notions of teaching and learning. The example case serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of self-determination in education and its potential to unlock the full potential of every student.

In conclusion, self-determination in learning is a crucial aspect of education that empowers learners to take control of their own learning process. It involves the fulfilment of three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. By promoting self-determination in the classroom, educators can create an environment that nurtures students’ intrinsic motivation, engagement, and overall well-being. It is important for teachers to provide opportunities for students to make choices, set goals, and engage in self-reflection. This fosters students’ intrapersonal, metacognitive, and interpersonal skills, enabling them to make meaningful choices, set purposeful goals, and take charge of their own education. Ultimately, self-determination in learning benefits both students and teachers, leading to increased engagement, motivation, and satisfaction in the educational journey.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Think about a time when you were highly motivated to learn something. What factors contributed to your motivation?

- What do you think self-determination means in the context of learning, and why might it be important for students to have control over their learning process?

- In what ways do you think providing choices to students can impact their learning and engagement?

- How do you think different learning needs (e.g., those of students with autism) should be accommodated to promote self-determination in the classroom?

Pick three to four of the following tasks:

Reflecting on the Example Case:

- If you were a teacher at Riverside Primary School, what strategies would you implement to further support Isaac’s self-determination in learning?

- How would you handle a situation where a student’s interests, like Isaac’s passion for dinosaurs, are not part of the standard curriculum?

Personal Application:

- Reflect on a recent learning experience. How did autonomy, competence, and relatedness play a role in your engagement and success?

- Identify one area in your learning or teaching where you can apply the principles of self-determination. What specific actions will you take to enhance autonomy, competence, or relatedness?

Strategies for Teachers:

- What are some practical ways teachers can provide meaningful choices to students in their daily routines?

- Discuss how you can use positive and informative feedback to boost students’ sense of competence and motivation.

Overcoming Barriers:

- Think about potential barriers to promoting self-determination in the classroom. What strategies can you use to address these barriers?

- How can teachers manage and respond to students’ negative emotions effectively to support their self-determination?

Evaluating Impact:

- How do you think fostering self-determination in learning impacts long-term student outcomes, such as their career choices and personal development?

- Discuss how self-determination theory can be applied beyond the classroom, in real-world situations and lifelong learning.

Literature

- It is worth noting that discussions around language and terminology related to disability can be complex and at times controversial. One key aspect of this debate is the distinction between disability-first language and person-first language. Disability-first language refers to using terminology that places the disability or condition as the primary identifier, e.g. ‘autistic boy’. Advocates of disability-first language argue that it acknowledges and embraces disability as an integral part of a person's identity and promotes a sense of pride and empowerment within the disabled community. On the other hand, person-first language emphasises the individual before the disability e.g. ‘boy with autism’ or ‘boy on the autism spectrum’, as is being used in this case study. Proponents of person-first language believe that it recognises the person beyond their disability, emphasising their humanity and individuality. It is essential to acknowledge that preferences regarding language and terminology can vary among individuals and communities. Some individuals and disability advocacy groups may strongly advocate for one approach over the other, while others may have different perspectives based on their personal experiences and cultural backgrounds. There is a growing recognition of the importance of centering the voices and perspectives of disabled individuals themselves in shaping the language used to describe and discuss disability. It is crucial to listen and respect their preferences and choices regarding how they wish to be referred to, as they are the experts of their own experiences. Ultimately, the goal should be to promote inclusivity, respect, and dignity when discussing disability-related topics. Engaging in ongoing dialogue, being receptive to diverse perspectives, and staying informed about evolving language norms can contribute to creating an inclusive and respectful environment for all individuals. ↵