Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) and the Potential to Transform Young Lives

Zeynep Karaosman; Sevcan Karataş; Cynthy K. Haihambo; and Suzanne O'Keeffe

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“When I was a student at a STEM-focused school, comprehensive sexuality education was noticeably absent. In grade 8, our female biology teacher, faced with a classroom of mostly boys, chose to skip the topic altogether. The discomfort surrounding the subject meant that we never received any structured information on sexuality.

By grade 10, the gap became even more apparent. Our new biology teacher, realizing that the subject had been entirely overlooked, decided to address the issue in an unconventional way—by screening Woody Allen’s film Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask). Although this film provided some information, it was more of a brief and superficial foray into the topic. Consequently, much of our understanding of sexuality came from external sources such as the youth magazine Bravo, with its Dr. Sommer-Team answering questions, and a few neglected pages in our biology textbook.

Years later, reflecting on these experiences as I began my own journey in teaching, I was determined to do things differently. I recognized the importance of not only providing factual information but also teaching students how to navigate discussions about sex in various contexts. In my classes, I made it a point to include sessions on “how to speak about sex” appropriately. I engaged students by collecting vocabulary related to sexuality and collaboratively deciding which terms were suitable for different settings and which should remain within more private discussions (and what words maybe better stay in the DIY section).

This personal journey from receiving incomplete and piecemeal information to developing a classroom that embraced open, contextual, and inclusive conversations about sexuality has shaped my approach to teaching comprehensive sexuality education today.”

Frank J. Müller, University of Bremen, Germany

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) and how does it differ from traditional or faith-based approaches to sexuality education?

- What are the key components of CSE, and how do they address the cognitive, emotional, physical, and social aspects of sexuality?

- How does a rights-based approach underpin CSE and contribute to empowering young people to make informed decisions?

- In what ways does CSE cater to diverse learners, including those with different cultural backgrounds, gender identities, and special educational needs?

- What common myths about sexuality education does CSE challenge, and how does it foster a safe and inclusive learning environment?

Introduction to Topic

Teaching sexuality education can take different approaches. These approaches include faith- and culture-based, public health, and rights-based approaches. Faith- and culture-based approaches to sexuality education take “moralistic” views on sexuality. Public health approaches are concerned with health-related matters such as sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs), using contraception, communication skills and unintended pregnancies. The rights-based approach emphasises the principles of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) with content taught beyond pregnancy and disease prevention (for more, see Wangamati, 2020). Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) takes a rights-based approach to teaching sexuality education. CSE is understood as a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about aspects of sexuality. It is concerned with learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical, and social aspects of sexuality (WHO, 2010). CSE was first introduced in Europe by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) in 2006. It became more widely used when adopted by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA, 2014, 2015) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2015, 2018). Good quality sexuality education is grounded in internationally accepted human rights, including the right to appropriate health-related information (European Expert Group on Sexuality Education, 2016). International agencies such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2009) are consistent in the belief that sexuality education reduces sexual risk-taking behaviour, protects against sexual abuse and that a child’s access to sexuality education is crucial for building competency, as well as understanding one’s own sexual subjectivity (Robinson, 2012). CSE is an approach that offers breath and depth across knowledge, skills and attitudes to sexuality education. This will be explored more in the following section.

What do you mean by comprehensive sexuality education?

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality (WHO, 2010). Depending on the country or region, CSE may go by other names. It may be referred to as ‘life skills’, family life’, or ‘HIV’ education (UNESCO. 2017). It is sometimes called ‘holistic sexuality education’. CSE seeks to empower children and young people by equipping them with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will inspire them to realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives (UNESCO 2017). Traditional models of sexuality education, as described above, took a risk-based approach focusing on biology and reproduction and are often informed by religious values and standards. Comprehensive sexuality education extends beyond those areas to include eight key concepts: relationships; values; rights; culture and sexuality; understanding gender; violence and staying safe; skills for health and well-being; the human body and development; sexuality and sexual behaviour; sexual and reproductive health (UNESCO, 2017). These key concepts aim to equip children and young people with age-appropriate and accurate information about sexuality such as information that dispels myths; about sexual and reproductive rights/health; references to useful resources and services, and information about sexually transmitted infections-STIs. They also develop skills such as decision-making and theability to take responsibility and create positive attitudes and values. This results in a broader set of outcomes, which include caution against of homophobic bullying, intimate partner violence, and child abuse; understanding of sexual orientation and gender diversity; and promotion of healthy relationships, social emotional learning, and media literacy (for more, see Goldfarb and Lieberman, 2021).

Why do we need comprehensive sexuality education in our classroom?

Comprehensive sexuality education is needed in our classrooms for numerous key reasons. First, it is a central consideration of global education agendas. CSE is directly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), in particular the SDG 3: Health; SDG 4: Education, and SDG 5: Gender Equality. It is also a key recommendation in HIV and health agendas. In a 2010 report on sexuality education, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education stressed that sexual education should be considered a right in itself and should be linked with other rights. The need for comprehensive sexuality education is also acknowledged in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of the United Nations and in the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (UNESCO 2017), which states that CSE is needed so that children and young people can access reliable and scientific information appropriate to their age, become individually stronger, and ensure social peace. However, many sexuality education programs delivered in schools are from a risk-based perspective that are underpinned by biology and the traditional view of sex for reproduction. Large-scale international reports suggest that the emotional, social and health needs of young people are not being fully met from this vantage point (IPPF, 2010; UNESCO, 2021; WHO, 2021). Youth mental health is a growing concern across Europe with the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) reporting that depression, anxiety and behavioural disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability among adolescents and suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among 15-19 year-olds. UNESCO (2021) details important gender differences in youth mental health such as girls reporting a higher prevalence of sexual violence and eating disorders. Restrictive gender norms increase psychosocial vulnerability amongst all adolescents involved in the study across the globe. CSE plays a critical role in school-based sexuality and gender education and is essential to build a safer society for everyone. It can combat and help prevent sexual violence and exploitation, gender-based violence and discrimination by providing factual, non-stigmatizing information on sexuality and gender identity, promoting non-stereotyped gender roles, and educating children and young people about mutual respect, consent and non-violent conflict resolution in interpersonal relationships.

What should we teach in CSE?

Knowledge, skills, attitudes and values underpin CSE teaching. The content in this section represents what we should teach in CSE. This section draws from the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (2018) and is also informed by literature review of several other resources that are significant in delivering CSE content to the referred ages globally. This section outlines the first three key concepts, topics and learning objectives: relationships; values, rights, culture and sexuality, and understanding gender.

Key Concept 1: Relationships

We understand ourselves better through our families It allows us to locate our own family within a broader context of personal experiences, cultural values and societal trends. When combined, these factors promote greater personal understanding. Teaching young people about families brings many educational benefits. It introduces young people to difference, which challenges assumptions and beliefs, and promotes greater respect and inclusion.

Friendship, Love and Romantic Relationships

Friendships and relationships are fundamental to a young person’s growth and development. While it may appear that friendships and love evolve naturally, teaching young people about friendship, love, and romantic relationships is an important opportunity for young people to learn social skills. It facilitates young people in developing good communication skills and boundary setting and helps children understand what healthy and unhealthy relationships look like and how to report concerns.

Tolerance, Inclusion and Respect

Introducing young people to issues of tolerance, inclusion and respect has been shown to increase creativity, open-mindedness and encourages a life-long appreciation of respect for difference. This topic promotes a better understanding for young people of self-knowledge and encourages prosocial attitudes and practices crucial for accepting and respecting others for who they are.

Long-term Commitments and Parenting

Introducing young people to positive parenting practices promotes safety, well-being, and a sense of permanency. UNESCO (2018) provides comprehensive guidance on the themes as well as the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are important under the categories of long-term commitment and parenting. The themes relevant to long-term commitments and parenting include:

- There are many different families that exist around the world.

- Different family members have different needs and roles.

- Gender inequalities are often reflected in the roles and responsibilities of family members.

- Love, cooperation, gender equality, mutual caring and mutual respect are important for healthy family functioning and relationships.

- Conflict and misunderstandings between parents/guardians and children are common, especially during adolescence, and are usually resolvable.

Key Concept 2: Values, Rights, Culture and Sexuality

Values and Sexuality

Values are strong beliefs that are learned in society/family and that are effective in shaping emotions and behaviours (UNFPA 2018). Different individuals, families and cultures have different values. Values can be influenced by many things such as religion, tradition, mass media, political and social situations. Children can learn their values by sharing with their parents/primary caregivers or other family members, religious teachings, teachers and friends. Values play an important role in children’s attitudes/behaviours that they will develop throughout their lives, their reactions to events/persons, and social relationships (UNFPA 2018). Sharing similar values within the family or in social environments is effective in developing stronger relationships; therefore, values can sometimes be accepted as they are and without reflection. Values are also effective in children’s development of positive or negative attitudes about sexuality. Positive values taught at an early age will help young people think about their own sexuality, respect others’ sexuality, and make positive decisions. They may change over time, but it is necessary to have access to accurate and accessible resources and materials.

Human Rights and Sexuality

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human throughout life and encompasses gender, gender identities, sexual orientations, relationships and reproduction (WAS 2014). Sexuality is an integral part of every person’s personality. The full development of sexuality depends on meeting basic human needs such as privacy, emotional expression, and compassion. The healthy continuation of sexuality is affected by the quality of the interaction between the individual and the social structures. Sexual rights are universal human rights based on fundamental rights such as freedom, human dignity and equality for all people. Sexual rights should also be one of the basic human rights such as health, education and housing. To develop the sexual health of individuals and communities, sexual rights must be recognised, encouraged, respected and defended by all societies.

Culture, Society and Sexuality

Every culture has norms about sexuality. In some societies, sexuality continues to be perceived as complex, mysterious and a source of fear. Sexuality has mental and behavioural aspects as well as biological and physical characteristics (UNFPA 2018). The most important factor in the development and change of young people about sexuality is the perspective of the culture in which they grew up. Cultural and societal perspectives on sexuality may differ from each other, and even regional differences within the same culture affect the view on sexuality.

Children receive messages from family, friends, the media and the environment about how to behave, which encourage children to conform to existing patterns and practices of sexuality. Young people ought to be encouraged to discuss sexuality in schools, social areas, with their partners and families because of different sexual values and beliefs. Many young people do not consciously choose their gender-related social roles. They have already gained their roles in the socialisation process that begins in childhood.

Key Concept 3: Understanding Gender

The Social Construction of Gender and Gender Norms

The social construction of gender comes from the theory of social constructionism which states that meaning and knowledge are socially created. According to the social constructionism theory, the things that are acknowledged as natural or normal in society, such as understanding of gender, race, class, and disability, are the result of social interaction and the rules imposed by the dominant groups in society. Until the last couple of decades, the word gender was used interchangeably with sex and therefore, gender roles are the roles that are assigned to people based on their sex. For example, men were – in some societies, still are- viewed as breadwinners and women as housewives and homemakers. This meant the public sphere of life, which includes involvement in political matters, paid labour and civil society, was/is associated with men. The private sphere, on the other hand, including family issues, household and unpaid labour was associated with women. These socially created gender roles not only put people in the category of man and woman but also decide how one must behave, present and perform publicly and privately.

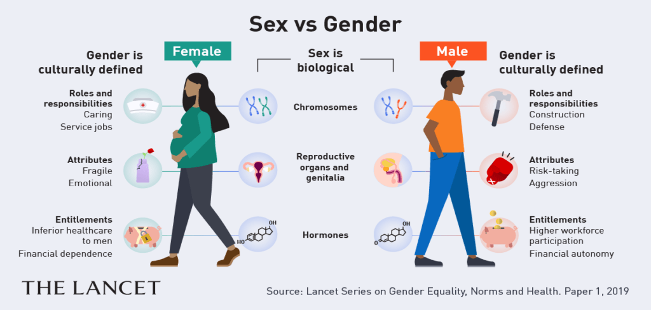

Figure 1: Sex vs Gender

Unlike the traditional definition, sex is a label assigned at birth based on the genitalia, chromosomes, and hormones one is born with (e.g., male, female, intersex), while gender is about the perception, understanding, and experience of a person about what they are meant to be and how they want to interact with the world (e.g., cisgender, transgender, non-binary, gender non-conforming, genderqueer, woman, man). Therefore, assuming someone’s gender identity or sexual orientation based on how they look and thinking that people are only attracted to the “opposite” gender, teaching that people are either men or women based on their body parts (cisnormativity) and ignoring non-binary and gender non-conforming people are all part of socially constructed gender norms.

Gender Equality, Stereotypes and Bias

Gender stereotypes are over-generalised assumptions and beliefs about individuals, and they reflect the perceptions and expectations about people that are solely based on their gender. The content of stereotypes and biases generally includes behaviours, physical and characteristic features, roles, preferences, attitudes, interests, and skills among others. They serve as a lens through which people view their social world and are constructed in minds as early as childhood. They influence the toys children play, the way they dress, the way they speak, the relationships they build, the school subjects they study, their entire experience of education, and their future careers and lives. These ideas come from all sorts of sources – families, schools, media, workplaces and so on. In order to ensure that every child is given the opportunity to reach their full potential, it is critical to challenge gender stereotypes and biases and teach kids about gender equality starting from a very young age. Children need to understand what gender bias is and how it shapes the society they live in. This can be achieved through non-gendered play activities, gender-neutral toys, books and stories that challenge stereotypes, and positive role models. Our role as educators is to challenge these gender norms, deconstruct gender stereotypes and promote gender equality in and out of the school. Children should unlearn and question these false and limiting beliefs about themselves and others and for that, we should prepare them to think outside of the “gender box”.

Figure 2: The Gender Unicorn

![A cartoon “Gender Unicorn” character stands on the left, colored purple with a rainbow thought bubble over its head. Five dotted arrows extend to the right, each labeled with a category and possible options: Gender Identity (e.g., Female/Woman/Girl, Male/Man/Boy, Other Gender[s]) Gender Expression (e.g., Feminine, Masculine, Other) Sex Assigned at Birth (Female, Male, or Other/Intersex) Physically Attracted To (Women, Men, Other Gender[s]) Emotionally Attracted To (Women, Men, Other Gender[s]) Text at the top reads “The Gender Unicorn,” and the graphic is credited to TSER (Trans Student Educational Resources). A small DNA strand on the unicorn’s side hints at the concept of biological sex. At the bottom, design credits mention Landyn Pan and Anna Moore, along with a link to learn more at transstudent.org.](https://book.all-means-all.education/app/uploads/sites/2/2024/01/neu.jpg)

Gender-based Violence

Gender-based violence is defined as acts or threats of physical, sexual or psychological violence directed against a person based on their gender or sex and enforced by unequal power dynamics. Gender-based violence is among the most common violence that exist in all societies and all cultures because of gender norms and stereotypes. Such violence can appear in many different forms:

Table 1: Types of gender-based violence

| Types of gender-based violence |

| Sexual violence: Includes actual, attempted, or threatened rape, including marital rape; sexual abuse and exploitation; forced prostitution; transactional/survival sex; and sexual harassment, intimidation, and humiliation. |

| Physical violence: Includes actual, attempted, or threatened physical assault or battery; slavery and slave-like practices; and trafficking. |

| Emotional and psychological violence: Includes abuse and humiliation, such as insults; cruel and degrading treatment; compelling a person to engage in humiliating acts; and placing restrictions on liberty and freedom of movement. |

| Harmful traditional practices: Include female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C); forced marriage; child marriage; honour or dowry killings or maiming; infanticide, sex-selective abortion practices; sex-selective neglect and abuse; and denial of education and economic opportunities for women and girls. |

| Socio-economic violence: Includes discrimination and denial of opportunities or services on the basis of sex, gender, or sexual orientation; social exclusion; obstructive legal practices, such as denial of the exercise and enjoyment of civil, social, economic, cultural and political rights, mainly to women and girls. For more, please refer to: https://www.unhcr.org/ |

What should we keep in mind when preparing CSE materials?

While teaching CSE, it is important to consider the needs of target groups/learners within the social and cultural contexts of their lives and to use variety of methods:

- Storytelling

Storytelling can be a very powerful tool when they are relevant and the learners can relate to them. - Brainstorming and making Flip charts

Brainstorming is a great method when introducing a new topic or solving a specific problem. The topic to brainstorm should be formulated into a question that has many answers. Write the question on a flip chart and ask learners to contribute with their ideas. The answers should be written as words or short phrases. At the end of brainstorming, the group can discuss the ideas. - Role-play

Role-play can be a key method especially when we want to encourage learners to empathise with others. Through imagining themselves in an unfamiliar situation, learners can realize how social stereotypes can be reproduced even when they are theoretically against them. Before asking learners to act out in a role play, it is useful to explain the objects and outcomes of the activity. It is also important to make sure no one feels excluded or marginalized. - Discussions

Discussions in small or large groups are vital to stimulate critical thinking and understanding important points of the topics. This method can be combined with the others by asking open questions such as; “What do you see here? Why do you think it happens? What can we do in order to prevent it?”. It is necessary to summarize the major ideas and to write them down at the end of the discussion. Otherwise, it can be hard for the learners to grasp the most important points and to understand their significance. - Using Media

Sources such as film clips, videos, songs or articles can be used as effective active learning materials. They can help especially young children learn complex subjects better. Learners can also be asked to create their own media like videos, writing and recording songs or articles about the topics they have learned.

In order to fulfill this comprehensive mandate of comprehensive sexuality education, the developers of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) material should consider these principles:

- CSE starts from birth and progresses in a way that is developmentally appropriate through childhood and adolescence into adulthood.

- It covers a comprehensive range of topics beyond biological aspects of reproduction and sexual behaviour, including (but not limited to) sexuality, gender, different forms of sexual expression and orientation; gender-based violence (GBV); feelings, intimacy and pleasure; contraception, pregnancy and childbirth; and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Human Papillomavirus.

- CSE is an evidence- and curriculum-based process of teaching about the cognitive, emotional, social, interactive and physical aspects of sexuality.

- CSE provide current, accurate information on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) that is publicly available and accessible to all, and incorporated into educational curricula, and in all spaces used by children and young people.

- It strengthens children’s and young people’s ability to exercise their sexual and reproductive rights to make conscious, satisfying and healthy choices regarding relationships, sexuality and their physical and emotional health while considering their lives at the current moment and for the future.

- It is based on respect for universal human rights, gender equality and diversity that underpins individual and community well-being.

- It helps young people to reflect on, understand and challenge harmful social and gender-based norms and the impact these have on relationships with peers, parents, teachers, other adults and their communities.

CSE is an integral part of the human right to health and support services; in particular, the right to access appropriate, adolescent-friendly sexual reproductive health and rights information and support-services. In addition, the content of and design of CSE material should be:

- Age- and developmentally-appropriate

- responsive to the changing needs

What role does diversity play in CSE?

For a long time, comprehensive sexuality education materials have targeted the “average” child or young person, irrespective of the diversity of humanity. We are referring here to diversity in terms of physical, cognitive, socio-cultural, emotional, socio-economic, political and any other characteristics. In the past, comprehensive sexuality education programmes have excluded, although unintentionally, children and young people with non-normative sexual and gender identities, disabilities and other special educational needs; from remote, rural and underserved communities, wreligious and traditional beliefs and other forms of diversities. In this chapter, we want to undo this form of exclusion by using the phrase: “All Means All” and arguing for inclusive, comprehensive sexuality education.

Why does LGBTQI+ inclusion in CSE matter?

Adolescence is a period when friends and social circle become very important. Many LGBTQI+ students hide themselves for fear of being ostracized and ridiculed by their friends and teachers. While invisibility and being ignored alleviates a severe aspect of violence and oppression, feeling restricted and unable to be authentic paves the way for discrimination to take place. In such cases, it is possible to talk about the existence of traumatic events, especially during adolescence, when sexuality is at the forefront. Adding LGBTIQ+ to CSE is essential important as it removes the veil of silence surrounding issues of inclusivity and diversity and gives students and teachers the confidence and competence in this area. This will help shine a spotlight on LGBTQI+ issues and concerns, promote an inclusive school and address homophobic and biphobic bullying.

How can we as educators create a safer space for everyone?

CSE programmes should be designed to ensure a safe and enabling environment for students, one that engenders a sense of comfort, openness, and safety. In the classroom, a facilitator can create a protective and enabling environment, also known as ‘climate setting’, by establishing ground rules, such as keeping confidentiality and avoiding making generalizations about any groups of individuals; demonstrating active listening by paraphrasing questions and contributions from learners; building trust, as demonstrated by a willingness to respond to all questions without shame or minimization; reducing showing your own bias by expressions of shock or judgment to what the young people share; encouraging contributions from learners in participatory ways, which communicates the value of the students and enables them to personalize and integrate the information and skills being taught. (UNESCO. 2015: 24).

How can we use language to open communication to open communication?

For effective and successful CSE classes it is important to set a number of agreed expectations beforehand to ensure that a safe learning space is created. The participants should be involved in generating these rules. This will make them feel more comfortable and safer. Some expectations might include:

- The personal stories shared and discussed here will not be shared with someone outside of this group.

- Everyone has the right to share and not to share their personal stories.

- We have no right to share stories or experiences of others.

- No question is stupid or not worth asking.

- We will take responsibility for challenging harmful prejudice and oppression and reflecting our own prejudice.

What are the challenges we might face during CSE?

UNESCO (2019) acknowledge resistance to CSE in some communities. The barriers to CSE implementation include social opposition, which may negatively affect other areas such as policy-makers; the availability of and teacher access to appropriate curricula and training resources covering a comprehensive range of key CSE topics; teachers’ attitudes and readiness to deliver a curriculum and create the right classroom conditions for effective teaching and learning; students’ motivation; and parental concerns and lack of cooperation. High teacher attrition rates, or high-turnover, is also noted as a barrier to CSE as are changes in educational administration such as a change in minister impacts on CSE implementation strategies and their momentum.

Exploring common myths and facts is an effective strategy in addressing underlying assumptions and biases that might prevent effective CSE implementation.

Table 2: Myths and Facts

| Myths❌ | Facts✅ |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive sexuality education encourages children and young people to engage in sexual contact and desensitizes them to sexuality

|

Comprehensive sexuality education program helps young people to fully understand sexuality, delays sex, and use condoms or other contraception effectively

|

| Comprehensive sexuality education programs teach young people to consent at all times about sexuality and undermine parent/family authority

|

Comprehensive sexuality education is much higher quality and inclusive than the sexuality education that families will give to their children. These education programs define the role of parents in sexuality education and create a supportive environment

|

| Comprehensive sexuality education disregards values and promotes homosexual/bisexual behaviour.

|

Comprehensive sexuality education supports a rights-based approach that includes values. It gives young people the opportunity to discover and define themselves. Moreover, it includes respect, acceptance, tolerance, equality and empathy for other individuals, cultures and societies

|

| Comprehensive sexuality education teaches teens the mechanics of sex | Comprehensive sexuality education is planned according to the needs of age groups. Information such as family structure, body parts/structure/names, consent, changes in puberty, infectious diseases, making decisions about relationships, contraception methods and pregnancy are included in the education content according to age groups. How to have sex is not included in comprehensive sexuality education

|

| Comprehensive sexuality education highlights inappropriate condom use and provides inaccurate information about condom effectiveness.

|

Condom use is very effective in preventing HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies. Comprehensive sexuality education programs are not used as a tool to control population growth. Comprehensive sexuality education emphasizes the importance of using condoms, but not by using sexually explicit and/or sexually entertaining methods.

|

Adapted from Sulava D. Gautam-Adhikary (2011) Myths and Facts About

Comprehensive Sex Education Research Contradicts Misinformation and Distortions. Advocates for Youth.

https://www.advocatesforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/storage/advfy/documents/cse-myths-and-facts.pdf

How can we be more inclusive of children from different cultural backgrounds?

In order for teachers to effectively deliver barrier-free, inclusive CSE to all children and young people in their care, they need to develop attitudes, skills and materials that speak to the wide range of diversity of their learners. It is advisable to conduct an index of the students to get an understanding of their backgrounds, belief systems and traditional practices in their communities. This sounds like a mammoth task which no one should attempt to do in one week and tick off. It is a long-term process that requires an open mind and introspection of one’s own value system and biases. A value -audit will help teachers to determine their own opportunities and irritations to teach CSE and seek support. This process should prepare teachers to develop material that is bias-free, barrier-free and non-judgmental. In different parts of the world, Comprehensive Sexuality Education is delivered in different ways as deemed appropriate to that particular setting. The following includes guidance and questions to ask when considering diversity and inclusivity in teaching: does the programme represent the cultural backgrounds of those you are teaching? Is the programme respectful of different languages, cultures and social structures represented in those you are teaching? Are there materials suitable for children with neuro-diverse, sensory and cognitive conditions? Do the textbooks and worksheets include representations of race, gender, religions or other forms of diversity? Does the material refer learners to a counseling support group or adolescent-friendly reproductive health clinic, yet it does not exist in the school or community? If some of the answers to the questions above are NO, what adaptations will need to be made?

Conclusion

Sexuality education is an important part of human development and starts from, through all developmental stages such as early childhood, late childhood, puberty, adolescence, adulthood and old age. It is intended to support and protect children and young children sexual development. It aims at providing tools to empower children and young people with factual knowledge, skills and positive values to understand and enjoy their sexuality, while maintaining safe and fulfilling relationships. Furthermore, comprehensive sexuality education capacitates children and young people to take meaningful decisions for their lives and take responsibility for their own and other people’s sexual health and well-being. It provides them with tools to negotiate their rights and values amidst cultural and structural barriers.

Comprehensive Sexuality Education was traditionally approached from a medical, disease prevention perspective, the international trend is to prescribe to a more holistic approach including areas of positive relationships and individual as well as group wellbeing. The move from the medical perspective is also accompanied by a balance between the focus on the anatomy and the socio-cultural aspects of wellbeing.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Reflect on your own journey as a young person in their puberty and early adolescence years. How did you access information related to your changing body, emotions, and feelings? Who/ What helped you cope with these changes? What do you wish you were told before you experienced it? Now ask your students to do the same and discuss the issues that come from this exercise with your learners.

- Ask learners to place questions they want to ask about the topic of comprehensive sexuality education or worries they have in a box. Also ask them how they prefer you to respond to those questions. Consult with your colleagues (be selective of whom you include) and develop a strategy for responding to those issues. Where you need to refer learners for further help beyond your scope, please do so while following the relevant referral steps.