Section 1: Developing Inclusive Educators

Teacher Agency and Inclusion

Sara Baroni; Rhianna Murphy; Madhusudhan Ramesh; Günalp Turan; and Tamara van Woezik

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“In a primary school classroom, a teacher reviewed her scheme of work for the upcoming unit: Inspirational People. The curriculum featured well-known historical figures such as Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin, undoubtedly significant, but with a noticeable lack of diversity. As she looked around at her students, most of them girls and many from different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds, she wondered whether they would see themselves reflected in these examples.

Wanting to make the lesson more inclusive while staying within the learning objectives, she decided to expand the range of figures covered. Alongside Newton and Darwin, she introduced Mae Jemison, the first African American woman in space, and Martin Luther King Jr., a key figure in the Civil Rights Movement. As the lessons progressed, she noticed a shift the students: they showed greater engagement as they started to ask more questions.

By making these changes, she aimed to provide her students with a broader and more diverse set of role models opening their future perspectives.”

(Observation in a primary school conducted in the UK).

This example illustrates how teacher agency can play a crucial role in creating a more inclusive education for all learners. As discussed in this chapter, teacher agency is a multidimensional and complex concept that encompasses individual capabilities, contextual factors, and the everyday decisions teachers make in their practice. Understanding teacher agency – and learning how to become an “agent of change” both within and beyond the school environment – can have a meaningful impact, shaping more equitable learning environments for all.

Initial questions

- What is teacher agency?

- Why does teacher agency matter for inclusion?

- What are the elements of teacher agency?

- How can teacher agency be supported in a professional context?

- How can teacher agency be achieved?

Introduction to Topic

With continuous social changes and increased globalization, the education system is experiencing pressure to adapt and prepare children and students to face related challenges. Teachers around the world are called upon to drive this transformation, and become? “agents of change”. Yet to study the concept effectively, it is crucial to clarify the objectives and scope of this change (Pantić, 2015; Pantić & Florian, 2015). Furthermore, there is a need for a better understanding of what this role involves and thus, what teacher agency means.

In this chapter, teachers are seen as crucial actors capable of making significant strides towards inclusion and social justice (Pantić & Florian, 2015). Recalling the legacy of the Education for All Movement (UNESCO, 1990; 2005), the Salamanca Declaration(UNESCO, 1994), the SDG4-Education 2030 and the Incheon Declaration agreed at the World Forum on Education in May 2015 (UNESCO, 2015) that inclusion and equity should be considered the essential foundation for quality education (Ainscow, 2020). Within this framework every learner matters and therefore it is necessary to recognise the disparities and barriers that some learners may encounter in the access to a good quality education, enhancing their possibilities of learning and participation (ibidem). Equityrefers to the principle of fairness that every educational system should encompass, developing strategies and plans for promoting lifelong opportunities for all (UNESCO, 2015; Ainscow, 2020), and going beyond merely achieving high measurable standardised performance (Seitz et al., 2023). Accordingly, adopting a social justice approach means ensuring everyone has the conditions necessary to develop their capabilities and participate as equal citizens within society (Nussbaum, 2006). Policies should therefore aim to create environments that support the growth of each person’s capabilities and promote inclusivity, reflecting a commitment to participatory justice and equal citizenship.

In some countries inclusive education is generally associated with integrating children with disability into general school settings, however, a more broader perspective of inclusion is adopted here. Conceptual difficulties exist when defining inclusive education, particularly since the meaning is often highly contextual. Ainscow and Booth (2002) describe inclusive education as the process of increasing participation and decreasing exclusion. On this basis, it is important that teachers learn how to recognise exclusion and actively intervene – in other words, being agentic – in order to “mitigate the external causes of educational inequality” (Pantić & Florian, 2015, p. 334). Hence teachers themselves cannot remove structural inequalities, but instead, through their awareness, act by preventing their reinforcement? High quality teacher training that develops “reflective practitioners” (Schön, 1993) who can recognise and implement inclusive practice that values participation, can thus help every learner to foster his/her potential (Seitz, 2024).

For this reason, we will explore, in this chapter, the individual and contextual factors relating to teacher agency, and specifically adopt an ecological perspective. Initially we must define teacher agency (Section 1), and why teacher agency matters for inclusion (Section 2). We the describe elements of teacher agency using a case study example from the research experience of one of the authors (Section 3). In paragraph 4, we describe how professional development can support teacher agency, and finally, in Section 5, we provide a more practice-oriented section in attempting to explain how teachers can achieve their agency.

Key aspects

What is teacher agency?

Teacher agency can be a challenging concept to define and may be interpreted differently in various contexts. For instance, agency might refer to a company, or in some countries, a supply teacher. A common understanding, especially amongst sociologists, is that agency is an innate human capacity or capability (Giddens, 1984; Bandura, 2001; Bandura, 2006; Barker & Jane, 2005; Emirbayer & Mische, 1998): something which the individual either possesses or not. A potential difficulty with these approaches is that agency is viewed as individual responsibility. This may disregard social or organisational pressures that an individual has little control over.

Recently, there has been a move towards a more ecological approach to agency (Priestley et al., 2015; Li & Ruppar, 2020). This perspective views agency as the capacity of teachers to make choices and take purposeful action in their professional contexts. It emphasises that agency is not a fixed trait or a personal attribute, but instead is situational, emerging from the interplay between individuals and their environments (Priestley et al. 2015). One reason why teacher agency can be hard to define is that it is not always visible. For example, when a teacher decides to teach about Ancient Egypt, this choice may be a result of their intention to relate to their students’ backgrounds and needs, or it may be a result of working within a restrictive method that prescribes this topic. Therefore, what we see the teacher do might be a result of teacher agency, but it is not the agency itself. In other words, the process behind how teachers make these decisions is often not apparent.

Teacher agency refers to “action with intentionality, the capacity to formulate possibilities for action, active consideration of such possibilities and exercise of choice” (Priestley 2016, p. 23). Rather than focusing on whether a teacher has or doesn’t have agency, the focus is on “how teachers may achieve agency in their everyday settings and what might help or hinder in this” (ibidem, p.14). This perspective places teacher agency as something emergent, something achieved by individuals in their present contexts (Emirbayer & Mische, 1988). In other words, teacher agency is not only the capacity for an individual to act, but also the interplay of the environment the individual is in, their background, knowledge and experiences, the resources and relationships, and aspirations for their future self and their learners (Priestley, 2016).

Why does teacher agency matter for inclusion?

The social justice agenda of inclusive education is a response to the segregation of children based on their ability and disability. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994) were among the key developments which shifted the focus from special education to inclusive education in terms of the education of children with disabilities. Today, the concept of inclusive education has expanded to incorporate all forms of marginalisation.

The work of inclusion (in a school) may be classified as access, participation, engagement and achievement of all students where process, roles and structures are developed towards the intention of inclusion. Within this agenda, teachers are called upon to highlight the process of inclusion and are often referred to as agents of change (Fullan, 1993 ; Pantić, 2015). Teachers play a vital role in realising inclusion since access or entry into a ‘regular’ school does not guarantee inclusion into the classroom.

As classrooms across the world become more diverse (due to geo-political reasons and as we embrace a more disability-inclusive policy) teachers will need to reflect on their practices and ensure every learner feels included (Florian & Spratt, 2014). When teachers deepen their understanding of their context (students’ backgrounds), they are more likely to feel equipped to create an inclusive environment. However, an important prerequisite to enable this is to create an environment that encourages teacher agency to thrive.

If teachers are best placed to raise awareness about social justice, we must consider how best they can be supported. It is widely recognised that motivation for work depends on whether people feel that they can act on their values and competencies (Ryan & Deci, 2000). They also need to feel supported and competent in their endeavours, which therefore requires a supportive network to help them achieve agency (Chirkov et al., 2003). The achievement of agency can also lead to greater job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is important because teachers are under increased pressure due to multiple teaching demands. For instance, teachers face a range of issues such as ongoing staff shortages, high turnover rates, and an increasingly diverse student population. Consequently, the workload of teachers has increased while their well-being is declining (Sandmeier et al., 2022). Teachers may feel overwhelmed, nevertheless tapping into agency might help to regain a sense of control and thus promote well-being (Burger et al., 2021). In this sense, agency is also related to the concept of resilience (see Box A). When supporting teachers, it is important to understand that agency is not viewed as another teacher activity, but rather as a way to empower teachers.

Resilience and agency

Resilience and agency are often used interchangeably? and even though they are interconnected they should be defined separately. Defining resilience is not an easy task, given the growing recent number of studies and research paradigms. The psychological definition understands resilience as the process and the outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences (APA, 2018). However, this perspective carries the risk of reducing teacher resilience to an individual’s behavioural adjustment to external and internal demands, overlooking the critical roles of contextual factors and the potential for “being agents of change”. In contrast, we adopt an ecological perspective, as articulated by Ungar (2012). In this regard, when people face significant challenges, resilience refers to their ability to find and use resources that support their well-being, working individually or together to ensure these resources are used according to their culture (Ungar, 2012). This broader perspective highlights the interplay between individual and environmental factors in fostering resilience.

Despite the limited research on teacher resilience within inclusive learning environments, a recent sociological structural model sheds light on the complexity of this phenomenon. This model, developed by Mu et al. (2024), frames resilience as a dynamic process encompassing individual capacities, structural constraints, and teacher agency. Notably, even under the pressures of emotional exhaustion, neoliberal challenges, and the risk of teacher de-professionalisation, teacher agency plays a pivotal role. By harnessing agency, teachers can foster positive outcomes, mitigate negative consequences, and sustain their resilience over time (ibidem).

We understand this model to imply that teacher agency, as well as resilience, are best understood from an ecological perspective. Hence, this short reflection highlights the importance of looking for definitions of concepts that do not reduce complexity but show the multidimensional character of the terms used.

Box A. Relationship with the concept of resilience.

In conclusion, teacher agency plays a critical role in creating an inclusive classroom, particularly as teachers are in the best position to identify the needs of the students and raise awareness about diversity issues. It is also crucial for job satisfaction and well-being, in order that teachers feel competent in addressing inclusivity issues. Changes towards a more inclusive educational approach is a way to both engage in professional development and shape teacher agency. Florian and Pantić (2017) highlight the importance of teacher education in fostering critical thinking and situating professional autonomy (see Box B) within the broader work context. This perspective underscores the need for systems and structures that enable individuals to recognise and act upon the possibilities for making a difference. In the next section, the discussion will explore the elements of teacher agency, emphasising how they are shaped by and interact with the ecological context, including institutional, cultural, and policy-related factors.

Autonomy

Box B. Difference between autonomy and agency.

What are the elements of teacher agency?

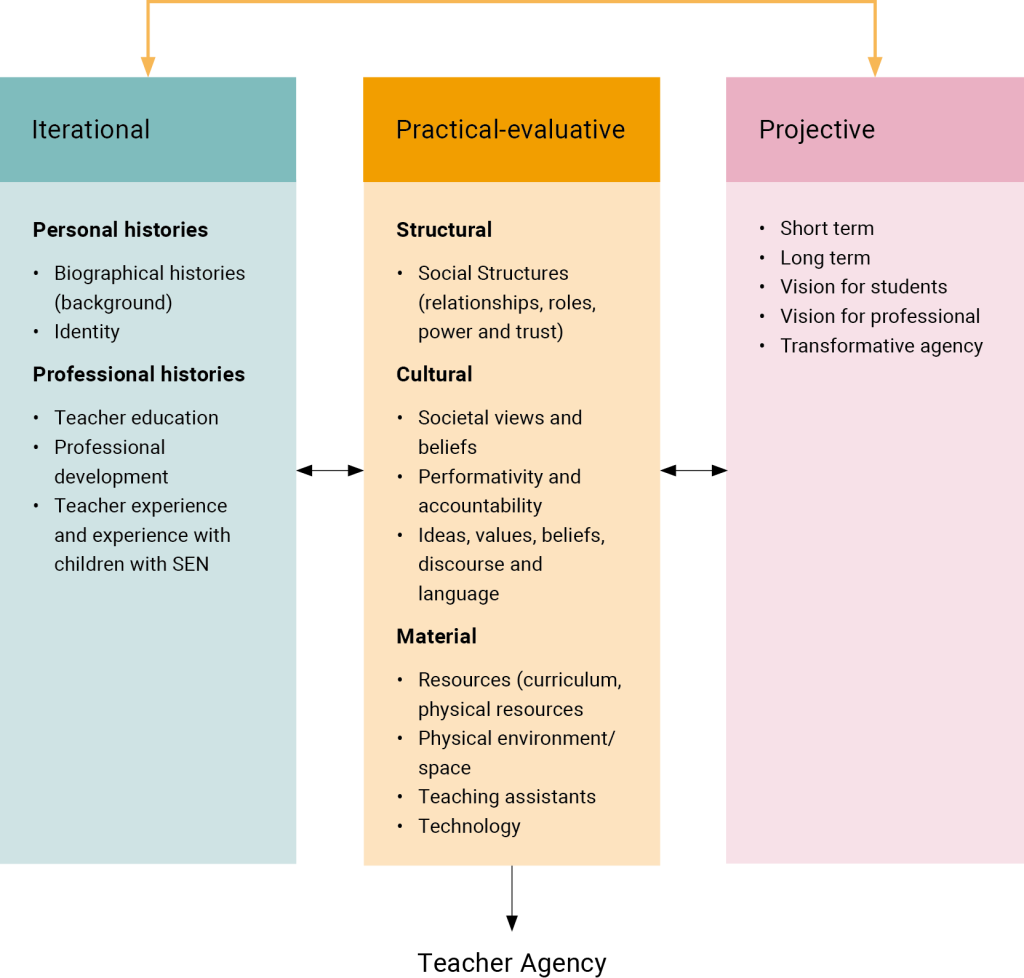

Teacher agency can be conceptualised in multiple ways. This chapter adapted an ecological model of teacher agency first introduced by Priestley, Biesta and Robinson (2016). This model claims that teacher agency is built up of three elements: iterational, practical-evaluative and projective. Whilst this model splits agency into three elements, an interplay exists between the three elements (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Model of elements in achieving teacher agency

The figure shows three boxes next to each other, the first ‘iterational’, the second ‘practical evaluative’ and the third ‘projective’. The boxes have arrows between them to show that they interact with each other. The arrow underneath the three boxes points towards ‘teacher agency’.

Initially, the model is briefly explained. Subsequently, an example is used to dive deeper into the different factors within the model.

The iterative dimension of agency is the element of teacher agency which has a past orientation. For example, this would include a person’s experiences, both professional and personal, and their knowledge and skills as well as professional learning and childhood educational experiences.

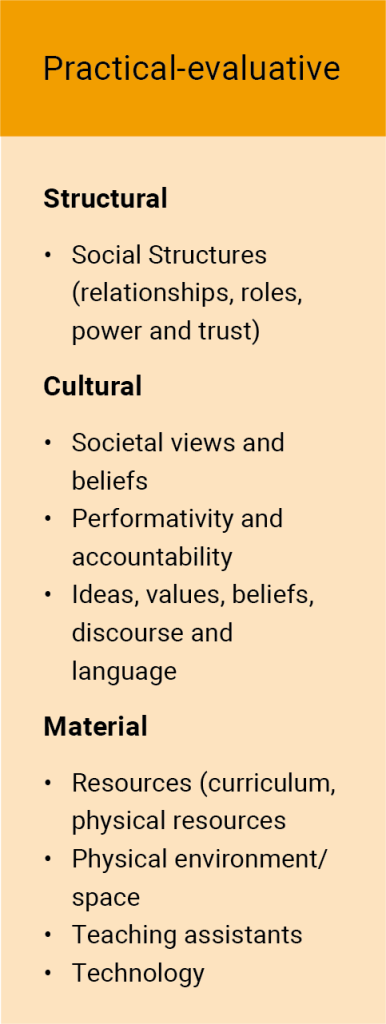

The practical-evaluative element has a present orientation and is the only element where agency can be acted out. This element focuses on the context within which a teacher works such as materials (resources and physical environment), social structures (relationships with staff and children, and school level and national policy) and culture (school and societal views).

Finally, there is the projective element which has a future orientation. This includes long-term and short-term goals. In other words, it focuses on visions and aspirations that a teacher has for themselves and also for their learners.

Building upon Priestley and colleagues model, our understanding of agency, and the elements shaping it, underscores the interconnectedness and interactions between factors. By using Freire’s definition of praxis, it can be argued that action and reflection employed by educators may have an intention to change the world (Freire, 1970). Therefore action can contribute to projective visions and as an iterative process, reflection can further improve teaching practices (Kemmis & Smith, 2008). Therefore, we identify bidirectional interactions between the factors, each affecting the other. The ecological model allows us to conceptualise the different elements that constitute teacher agency, whilst at the same time viewing the interplay across other elements. For example, if a teacher has past experiences of feeling excluded in their classroom as a child (iterational), this has the potential to influence their aspirations for the future (projective). For instance, ensuring that her own learners do not feel this way and aspire to achieve an inclusive classroom. This then could influence the decisions she makes today in the classroom (practical-evaluative). In the next section, a case study example is shown, which is used to further illustrate the terms of this ecological model of agency.

Rebecca’s story of inclusion and agency – a case study

Rebecca* works as a teacher within a special needs department at St. Augustine High School* in India, a school that has a hundred-year-old legacy. The school, like many private schools in India, segregates students in three ways: the ‘average’ and ‘above average’ achieving students who go to the mainstream school, the ‘low’ achieving students (many of whom may have learning difficulties) who go to a separate section at the same school. This section has more flexibility in the curriculum, learning processes and a different school-board called National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). The third section, known as the special unit, is for children with disabilities. Before Rebecca took on the role of a teacher within the special unit, she worked as parent-volunteer in the school for three years, during which time she also gained a diploma in inclusive education. She says: “I would have preferred to work in a role which acts as a bridge between the different [segregated] sections… but I was given this role”. Within two years of taking up the role, Rebecca has enacted inclusion in three distinct ways.

First, she ensures her classroom activities engage every child (no one must be left behind). There are alternatives for every task as well as alternatives to how it can be done. There is room for children to sit together at a community table or sit separately if they want to work independently. Rebecca sometimes finds that it difficult to reach children with her instructions, so she also uses visual aids and drawings to communicate. She invites her colleagues from other departments of the school to visit her classroom to seek their feedback.

Second, she uses her time on the school bus to ask her peers about their methods of working with children with disabilities or difficulties in their classrooms. She enjoys this daily commute with her peers as it allows them to talk freely about various school issues and she finds her colleagues more receptive to her ideas while on the bus. Though teachers are not open to a system where children with disabilities are integrated into the ‘mainstream’ classroom, they are still curious about how Rebecca works with children with disabilities.

Third, she nudges the school management to consider making the school more inclusive. Through her diploma, Rebecca learnt to look at her school from a theoretical lens and was able to analyse the different functions of the school. During her diploma, she also developed a few long-term goals and her own vision for her school. With the support of the management, she recently conducted a school-wide survey about teachers’ awareness of inclusive education which led to important discussions in the staff rooms and faculty meetings and further resulted in the management seeking guest lectures on the subject of inclusive education. Rebecca now has her eyes set on making school events (such as sports day) inclusive. She hopes to continue to take such steps to make gradual shifts in the school culture and practice.

Figure 2: Description of Rebecca’s agency in terms of the model of teacher agency.

In the middle of this figure stands a black-and-white woman, representing Rebecca. Around her are small boxes in three different shapes and colours, referring to the different elements of teacher agency. Blue circles refer to Iterative, orange hexagons to Practical-Evaluative and purple squares refer to Projective.

Implications of the teacher agency model for Rebecca’s case

Iterational

Personal Histories

Rebecca’s personal experiences include being a parent of a child with a disability. This role provides her with first-hand experience in understanding and working with children with disabilities. This could also enable her to empathise with other parents who have children with disabilities. These personal experiences equip her with valuable insights and knowledge that can shape her agency fostering inclusivity.

Professional Histories

Rebecca’s professional experiences are equally significant. She has spent several years working as a teacher with children with disabilities, during which time she has interacted with a diverse range of students. Her role as a teacher gives her a comprehensive understanding of the existing structures within her school. Additionally, Rebecca has pursued professional development in inclusive education, enhancing her knowledge and leading to greater competence in this area. These professional experiences contribute to her overall ability to support and implement inclusive practices in her classroom and school. In the case study of Rebecca, both her professional and personal experiences may impact the achievement of agency when it comes to developing an inclusive classroom and school environment.

In sum, the model highlights that the achievement of agency is always informed by past experience, and in this particular case, this concerns both professional and personal experience (Priestley, Biesta and Robinson, 2016).

Projective

The projective element encompasses both long-term and short-term aspirations and visions. In the case study, Rebecca’s proactive efforts to promote inclusion are closely tied to her long-term vision of creating a more inclusive school system. This alignment between her day-to-day practices and her broader goals helps explain her strong commitment to inclusion. Supporting this perspective, wider literature also illustrates how long-term goals can shape a teacher’s agency. For instance, Gu, Liang, and Wang (2020) conducted research on English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in China, revealing that these educators had long-term goals focused on ensuring student progress. These ambitions motivated them to take actions aimed at elevating the status of English in their local communities, thereby supporting the achievement of their long-term goals. Whilst the iterational element is discussed separately in this chapter, it is important to recognise its interconnectedness with other dimensions. For instance, Rebecca’s personal experience as a mother of a child with a disability and experience as a teacher may partly explain and motivate her vision to create a more inclusive educational environment. In other words, her personal journey could be providing the foundation for her aspirations (projective).

Practical-evaluative

Considering the practical-evaluative element of teacher agency, which encompasses structural, cultural, and material factors, we can analyse the factors affecting Rebecca’s agency.

Structural

In Rebecca’s case, certain policies and school structures might be hindering her agency. For example, school policy segregates children according to those with, and without, disabilities. This may restrict Rebecca’s agency as she is unable to make the decision to mix the classes.

The second structure which possibly could hinder Rebecca’s agency is that the prescribed, compulsory curriculum requires her special needs unit to take a more vocational approach to education, providing children with practical skills over disciplinary knowledge – resulting in restrictions on the curriculum content. According to Leijen, Pedaste and Lepp (2020) “educational policies that emphasise testing, accountability and efficiency have been heavily criticised for restricting teacher agency” (p. 296).

The case study also indicates that Rebecca’s agency could be influenced by teachers and senior management in her setting. For example, she exchanges ideas with other teachers and feels able to discuss inclusive education with them. This could positively influence the achievement of agency in the school and classroom environment as she may feel supported by others.

Cultural

Rebecca’s school, having a hundred-year-old legacy of serving the community it resides in, is moderate in making progressive decisions even when national policies encourage certain changes such as adopting inclusive education. It relies on the consensus among parents and staff opinion when considering changes. For instance, Rebecca’s approach to gently persuade the school management and her peers towards inclusive practices is based on her deep understanding of the school and its beliefs. Her agency comes from the cultural knowledge she possesses of the school from having been a parent, a parent volunteer, and now a teacher at the same school. Rebecca belongs to a city (societal context) where there are only a handful of ‘mainstream’ schools that include children with disabilities. Those who do include children with disabilities follow a similar model of segregation as her school. This is unsurprising, as noted by Singal (2019), teachers in India feel unprepared to teach children with disabilities alongside children without disabilities.

Rebecca’s school, which is built on Christian values, feels obligated to serve the community and all children (including those with disabilities). It also views children with disabilities in a charitable manner, which, in the short term, has aided Rebecca’s goal of inclusion and has given her agency to be a disability advocate, and to mobilise her peers towards inclusive practices.

Resources

Access to resources can significantly impact a teacher’s agency. For instance, Priestley, and colleagues (2016) claim that agency is partly shaped by the availability of physical resources and the nature of physical constraints. In Rebecca’s case, her classroom is spacious and specifically designed for children with disabilities. It includes numerous visual resources and calm areas for the children to use, setting it apart from traditional classrooms. These resources, and the ample physical space, allow Rebecca to select from a variety of visual materials and activities, creating options which may enable her to tailor her teaching to the needs of her students, and ultimately therefore creating the potential to lead to a more inclusive classroom.

To conclude, the analysis of Rebecca’s case identifies that there are many elements which hinder, and support, the goal of agency in her setting. Whilst this section has discussed the iterative, practical-evaluative and projective examples from Rebecca’s case study, it is important to note that there may be many more relevant examples and factors influencing the achievement of agency.

How can teacher agency be supported in a professional context?

To move towards more inclusive education, changes in the way of working in the school and in the classroom are required. To ensure that such transformations are successful, teachers must feel that changes are in line with their beliefs, and that they have the competencies or resources to contribute to this change (Palmer et al., 2017). This alignment can be shaped by reflection and discussion. School reform also relies on the professionalism of the teachers. During this process, teachers may have opportunities to explore their values and learn new professional skills (Imants & van der Wal, 2020). Such an exploration can help to further shape their values and competencies. As a professional (in training) it is important to recognise how your professional context can support you to achieve teacher agency.

In this paragraph, different professional contexts and how they can shape teacher agency will be further discussed, through the contexts of teacher education, early career teaching, and communities of practice. Finally, the role of reflexivity, as an overarching premise for professional development, is highlighted in the last section of this paragraph.

Teacher education

In teacher education, teachers can practise the achievement of agency in their settings. An overlap with student agency may also exist, as the student teacher may identify themselves as both a student and a teacher, depending on the programme. In some programmes, teacher education will include internships[1] in which student teachers have increasing responsibility over a class.

The teacher education context can be very valuable in developing teacher agency, by allowing sufficient time to learn by experimenting, and reflecting on, the curriculum (Korthagen, 2016). While still in teacher education, it may be difficult to achieve agency due to the hierarchical dependencies on a supervisor or teacher educator, in addition to balancing high workload with feelings of incompetence (Squires et al., 2022). However, there are ways in which student teachers can develop agency. They can reflect on how their personal goals relate to the course work or internship experiences, thereby increasing feelings of personal responsibility (Stockdale & Brockett, 2011). Within the limits of assignments, there may also be space to express one’s own views. While reading and discussing theory or literature, it can be helpful to ask how the readings relate to your own perspective. Such exercises can help to shape both the iterational and projective elements of teacher agency.

Within the context of a university or education institute, teacher educators can make sure there is room for exploration of the student teachers’ own values and related actions. This can be achieved by focusing on the student-teachers’ learning process, through self-directed learning methods for example (van Woezik, 2020) or by considering democratic or transformative learning methods (Freire, 1970; Vianna & Stetsenko, 2011; Stetsenko, 2019). These educational methods help students to set their own goals, while considering one’s own values and making room to discuss these values. By setting personal goals, even if they are bound by a curriculum, a sense of agency can be developed.

With regard to internships, the student teachers’ perspective is also valuable, particularly as new teachers can bring a fresh perspective to both the school and teacher education curriculum (März & Kelchtermans, 2020). Such ways of enacting agency are more informal and individual (Snoek et al., 2019). One could also think about more formal ways of enacting agency. For instance, by taking part in a student council or a council in the school in case of an internship. Moreover, one can achieve agency as co-agency (see Box C), meaning one could find like-minded peers or colleagues with whom they could voice any concerns or work on a project.

Co-agency

Co-agency refers to both individual and collective action to forge new possibilities in the institutional, political and societal power structures that frame the environment. Co-agency emphasises interactions, relations, networks and alliances as the building blocks for agency in guidance practice (Toiviainen, 2022).

The principle of co-agency understands that improving learning requires a joint effort between teachers and students. It highlights that teachers need to align their influence with the students’ own power to make a meaningful impact on their development. By applying co-agency in their decisions, teachers focus on enhancing the learning environment and opportunities, aiming to empower students to use their own agency effectively. This principle guides teachers to continuously consider how their actions can encourage and support students in taking charge of their own learning (Hart et al., 2014).

Box C. Defining the concept of co-agency.

Example

A student teacher created a chart of all the learners in their classroom, including the learning preferences and the type and quantity of contact they needed from the teacher. Based on this, the student teacher made a new seating plan where children with higher levels of distractibility would be in the front and centre of the classroom to have as little sensory input as possible, and children with social anxiety would be further in the back having less eye contact with the teacher. The student teacher also mapped children who need encouragement in the walking routes, and those who work well in teams were placed further in the back so they can talk without disturbing others. They discussed the initiative with peers and teacher educators. In this way, the student teacher took advantage of the space in the teacher education curriculum to experiment with this way of seat planning.

In-Service Teacher Education

The role of in-service teacher education is to address challenges and dilemmas that teachers are likely to face at different stages of their careers and to also introduce new ways of teaching and learning to improve school processes and culture. In-service teacher education has the potential to not only improve the professional knowledge and skills of a teacher, but also to facilitate teacher agency. Indeed, research has shown that teacher agency includes directing one’s own professional growth and that of colleagues (Calvert, 2016; Imants & van der Wal, 2020). Fullan (1993) argues that a key ingredient for teacher agency is ‘mastery’, where sufficient expertise is required for educators to bring sustained changes to their context. He further states that “mastery involves strong initial teacher education and career-long staff development, but when we place it in the perspective of comprehensive change, it is much more than this. Beyond exposure to new ideas, we have to know where they fit, and we have to become skilled in them, not just like them” (Fullan, 1993, p. 4). If, for instance, any new ideas refer to an inclusive classroom practice, teachers will need to rely on their expertise and agency to make decisions on how, or when, they would implement the particular practice. Florian (2014) supports that same view by pointing out that inclusive practice requires teachers to continually develop their practice in order to identify improved ways to reach children. She makes the case for this by stating that the “difficulties students experience in learning can be considered as dilemmas for teaching rather than problems within students” (Florian, 2014, p. 291).

In-service teacher education is important for teacher agency as the projective element of teacher agency calls for teachers to have a vision upon which they can act. In-service teacher education therefore provides an opportunity or a platform where they develop skills that can help them achieve their vision. Fullan also claims that “People behave their way into new visions and ideas, not just think their way into them […] New mind-sets arise from mastery as much as the reverse” (Fullan, 1993, p.4).

In-service teacher education programmes often bring together teachers with varying degrees of experience and backgrounds and in doing so, creates room for collaboration and learning where teachers can share similar experiences which, in turn, may inspire greater teacher agency.

Example

Inspired by a course on autonomy-supportive teaching, a teacher decides to make more space for the children allowing them to choose where they want to work and how quickly they will go through the assignments. Children can also walk in and out of the classroom. The teacher wants to show colleagues this change in the classroom, and invites colleagues to come and observe how the children and the teacher themselves are working. After a short observation, the teacher and a colleague sit together. They discussed what was going well and identified areas for improvement, such as checking in on the children that are outside the classroom. The observation also led to a discussion about the role of the teacher, the core values (e.g., autonomy for the children versus transfer of knowledge), and how the teachers feel agency to enact such changes in their classroom.

Early career

As an early career teacher, one may feel like there is still a lot to learn. Early career teachers tend to have less experience, which previous research indicates may play a key role in the achievement of agency (Burkhauser & Lesaux 2017; Dampson, 2019). Some early career teachers can feel overwhelmed in the first period as a teacher, having responsibilities for their own classroom and getting accustomed to a new environment. However, it is also worth bearing in mind that teachers will have a lot to learn. As an early career teacher, one might bring a fresh perspective on the school and the classroom, thereby enabling them to identify practices that could be changed or addressed. Early career teachers also bring new ideas and insights that can be valuable for the school. This is called innovative professional potential (van Leeuwen, 2024). Innovative professional potential has been found even during stressful times of teachers’ careers, indicating that even though it is influenced by external factors, it is not always constrained by them. Oolbekkink et al. (2022) describe early career teacher’s agency across different categories ranging from restricted to extended. For example, teachers who experience restricted forms of agency can only enact agency within strict limitations relating to methods used in the classroom or school regulations. Teachers who experience extended agency often notice that they are invited by their school leaders and colleagues to experiment or expand their influence.

Example

I teach a year 3 class (7-8 year olds) in England. Our school uses a pre-packaged scheme of work which provides prescriptive topics, termly plans and descriptive lesson plans. The topics tend to be interdisciplinary meaning a range of subjects are integrated. This term, the topic has been Prehistoric Britain. This scheme of work is very restrictive as “what” I am teaching and sometimes “how” I am to teach are prescribed. For example, this week our objective in topic (history) was “to understand what Stonehenge looks like”. Stonehenge is believed to be a religious monument built in the prehistoric period. The scheme of work provided a PowerPoint presentation which identified facts and different parts of Stonehenge and a follow-up activity sheet for the children to complete labelling different parts of Stonehenge. However, I knew my class liked to build and do practical tasks. I asked senior management if I could get the children to make models of Stonehenge using materials in school, such as Lego, building blocks and cardboard, instead of using the worksheet. With the support of senior management, I was able to achieve agency within my classroom.

However, as a newly qualified teacher, the scheme of work has been beneficial (in some cases). For example, it supports my curriculum coverage and, by having pre-made resources, it saves me time as I do not need to create my own. Without having this scheme of work this year, I would not have known where to start planning my history lessons. I believe confidence with curriculum content and coverage will come with time and I hope to diverge further away from the scheme of work.

Picture A. Reconstruction of Stonehenge, photography of the author. The picture shows several wooden squares positioned upright and put in a circle, with sticks on top and smaller blocks in the middle of that circle.

Picture B. Photography of Stonehenge by Uliana Sova from Unsplash. The picture shows several stones positioned upright and put in a circle, with stones on top and smaller stones in the middle of that circle.

As a teacher, one can achieve agency in an informal way, meaning that one takes action in the classroom or in the school based on their initiative. This can be seen in the example above. Such an initiative might resonate with school leaders, and lead to a formal position. This means that whilst coming from personal effort, one might move to having an allocated role and time to work on these issues. Individual initiatives may also spark the interest of colleagues and lead to forming a group of colleagues with a shared vision or goal resulting in a collective way of working. Working in a collective is helpful to find support and more traction for one’s cause. Communities of practice are a specific form of this.

Communities of Practice

Although there are multiples terms used for the groups of professionals who work on an issue or just collaborate on a daily basis, (i.e., professional learning communities or learning communities), we can define them as groups formed by individuals who share a concern, a problem, an intention, or a passion about a topic that collaborates and interacts on a regular and consistent basis (Wenger, 1998). In this chapter, we will use the term “Communities of Practice” (CoPs) to refer to such groups, to highlight the notion of practice and reflexivity inherent in these groups.

However, it’s also important to make the distinction between other familiar structures in order to create a better understanding of how CoPs may interact with teacher agency. These familiar groups that may be mistaken for a CoP and are often identified as “teams”, “task forces”, “training groups”, and “networks” (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2023). While a team, task force, training group, or a network may have a focus on developing a product, solve an issue, follow premade curriculum in a time-bound process in which hierarchical relations may be present, a CoP focuses on collective learning and reasoning where the practitioners have the lead and share common values and a group identity (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2023). With this comparison in mind, let’s look at how teacher agency in the context of inclusion may benefit from engaging in CoPs. It is safe to say that there are multiple ways in which a CoP can foster agency and inclusion. Possible benefits can be categorised as follows:

- Shared Leadership: The inherent horizontal relationships between community members fosters individuals’ capacity to take action. This way of forming relationships also encourages people of the community to share the leadership role in addition to collaborative decision-making practices (Harris, 2003; Campbell et al., 2019). As a result, they provide a space for teacher agency to foster and nurture individual’s capacity to act on their visions.

- Collaboration & Reflective Practice: CoPs create a highly conductive and interactive environment for establishing effective collaboration among teachers by creating space for professional solidarity (Ayan, 2020). Therefore, the members share competences, skill sets, strategies, etc. In this collaborative environment, individuals also find a space to engage in collective reflection where they can critically analyse their practices and make more informed decisions (Schon, 1983). Moreover, the nature of collaborative practice also provides teachers with new resources which they may otherwise not be able to reach. It can also provide the teachers with privileged access to resources extending from personal experiences to documents and tools (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2023).

- Professional Development: CoPs provide ongoing, relevant professional development that supports teacher growth and responsiveness to new educational challenges (Desimone, 2009). CoPs also build knowledge capital involving human, social, tangible, reputational, learning capital (Wenger et al., 2011).

- Fostering Inclusion: CoPs promote understanding and respect for cultural diversity, enhancing teachers’ abilities to create inclusive classrooms (Gay, 2010). In CoPs, through teachers’ interaction, members can address diverse student needs, developing inclusive strategies and practices (Ainscow et al., 2006). As diversity is inherent in the CoPs, members can acquire different perspectives on issues. In addition, problem-solving activities within CoPs allows members to tackle complex educational issues, enhancing their critical thinking abilities (Jonassen, 2000). Engaging in collaborative inquiry and dialogue within CoPs also encourages the questioning of assumptions, exploration of diverse perspectives, and development of critical thinking skills (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009).

As school populations become increasingly diverse, teachers need to consider how to make schools more equitable and inclusive for all learners. CoPs provide opportunities to employ agency by allowing shared leadership, promote collaboration and reflection, support professional development, and at the same time foster inclusion. To summarise, it can be argued that a community of practice which fosters diversity has the potential to produce solutions that will meet the diverse needs of all learners. As previously mentioned, this stems from the fact that communities that encompass different perspectives and different modes of existence will generate a variety of solutions to problems, which will, in turn, pave the way for the creation of more inclusive solutions via classrooms (Ayan, 2020).

Reflexivity

Research has shown that reflexivity of teachers is crucial for agency, inclusion and social justice, as well as for professional development in general. In daily practice, teachers often report lacking the time to reflect on their professionalism, identity, beliefs, and values, nor having time to consider structural, cultural and material dimensions. Indeed, these are often taken for granted. In some school contexts, it is common to hear statements like “I’m doing it because we are used to doing so,” which indicates a lack of critical reflection on potential inequalities and the solutions needed to address them. The problem with unexamined presumptions within institutional contexts is that they can sustain unequal educational outcomes for certain students. Pantić (2017) discovered that even inclusive educators who believe in their crucial role in advancing social justice and removing barriers to education often perceive students and their families as vulnerable, and instead focus on helping them conform to existing standards. Without questioning their underlying beliefs about schools as politically neutral and equal-opportunity environments, these educators might view special schools or self-contained classrooms as more suitable for students’ well-being and safety, while also seeing disability as inherent and unchangeable (Broderick & Lalvani, 2017; cf. Li & Ruppar, 2020). In the literature, reflection has been inquired since the 1980s but there is not always consensus on its conceptualisation. In order to better clarify some key terms, this next section distinguishes between reflexivity, reflexive posture and reflective practice.

Reflexivity refers to an explicitly knowledge-oriented process that is based on a “complex network of relationships aimed at giving meaning to actions and stimulating new ones, and aimed at interpreting the experience through which we understand the reasons why we act in a certain way” (Nuzzaci, 2011, p. 11). In this definition, the role played by experience clearly emerges, which, paraphrasing Dewey (1986), can be understood as the interaction between subject and object, between organism and environment, and which manifests itself in problematic situations in which the individual tries to overcome a problem to respond to his or her own need or necessity. This process is similar to that described by Mezirow who conceptualises the transformative learning process as a series of stages through which an individual, starting from a challenging situation (which he calls disorienting dilemma), tries to revise its own schemes of meaning, reworking them and making them more appropriate to the situation, until coming to a new, more adequate conceptual perspective (Mezirow, 2003; 2016; crf. Baroni, 2021). Reflexivity is thus configured as a deep learning process, which also involves the emotional dimension of the subject, as well as the behavioural one (Nuzzaci, 2018). Alternatively, when one speaks of reflexive posture, one refers to an attitude “that is episodic and spontaneous in character and leads one to reflect discontinuously on a certain practice without an assumption of awareness or change in action” (ibid., p.11).

The third one, reflexive practice, is understood as integrally part of the teacher’s professional identity, since it consists in being able to operate a constant reflexive process to guide action, regardless of the obstacles or difficulties encountered (Altet, 2008; Perrenoud, 2001). Moreover, in this practice, the professional can recall possible functional strategies to carry out a given task. This shares commonalities with reflexivity in that it presupposes a habitus (Bourdieu, 1972), i.e. a way of acting in practice, constituted as much by actions, as by languages, rules, objectives and implicit strategies (Nuzzaci, 2011). Thus, it is the case that the practitioner in question is constantly engaged in a reflexive operation that leads him/her to become more and more aware and thus sustain his/her resilience (La Marca & Longo, 2016).

Engaging in reflective practice is not always easy, especially as an early career teacher or when you work in structures that do not foster such practices. Still, it may be worthwhile to look for possibilities. You can think about finding like-minded colleagues, with whom you can reflect during a coffee or lunch break. Perhaps there are opportunities within the school to find a mentor or other form of professionalisation that will help you find time for reflection. Or you might even address the issue with school management, perhaps together with other colleagues.

Underlining the role of reflexivity, and of being a reflective practitioner (Schön, 1993) is crucial while working towards the implementation of inclusive school practices. In particular, it is necessary to find space and time in which the individuals and the groups (crf. community of practice) can create opportunities to step back, recognise and assess situations of inequality, find solutions to leave behind routinised mechanistic practices, and act positively (Pantić, 2015).

We could understand reflexivity as a “superpower” that empowers teachers in monitoring both self and the society, enabling them to accomplish their purposes. Research has shown that educators that are able to reflect on their practice could positively enact change through agency, such as “reflecting on their own practices and environments in seeking to accommodate all learners; constantly monitoring their own actions with respect to their commitments (…); articulating practical professional knowledge and justifying actions; making sense of the structures and cultures in their schools as sites for social transformation” (Li & Ruppar, 2020, p. 48).

Example

In the “Action Research Teacher” programme facilitated by Teachers Network, a dynamic community of educators was established through ongoing discussions focused on inclusive classroom practices. Supported by the organisation, this community collaborated closely with experts from an inclusive education centre, engaging in a continuous cycle of observation, discussion, design, implementation, and reflection. As part of this process, teachers maintained observation diaries where they reflected daily on their own practices and classroom environments within the context of inclusion. These diaries often revealed exclusionary practices, discourses, and identified vulnerable groups and identities. Group reflections on these observations led to broader discussions and a sense of empowerment, enriched by the diverse experiences of the community members (Yurtseven et al., 2021).

How can teacher agency be achieved?

As teacher agency is understood more as an ecological concept instead of an individual capacity, our answers on how to achieve teacher agency should also adopt an ecological approach. As discussed in this chapter, teacher agency should not be defined as another task or a skill that teachers need to complete or achieve on their own. In order to understand how to develop agency inside the ecosystem shaping agency, the system itself and its actors need to be highlighted. Priestley and colleagues (2021) identify five distinct sites of activity including; nano, micro, meso, macro, and supra, that interact in the context of teachers’ classroom practices. Although they offer a model for reframing the curriculum making process, the same ecological model can be applied to teacher agency, as the actors and the sites of activities do not change.

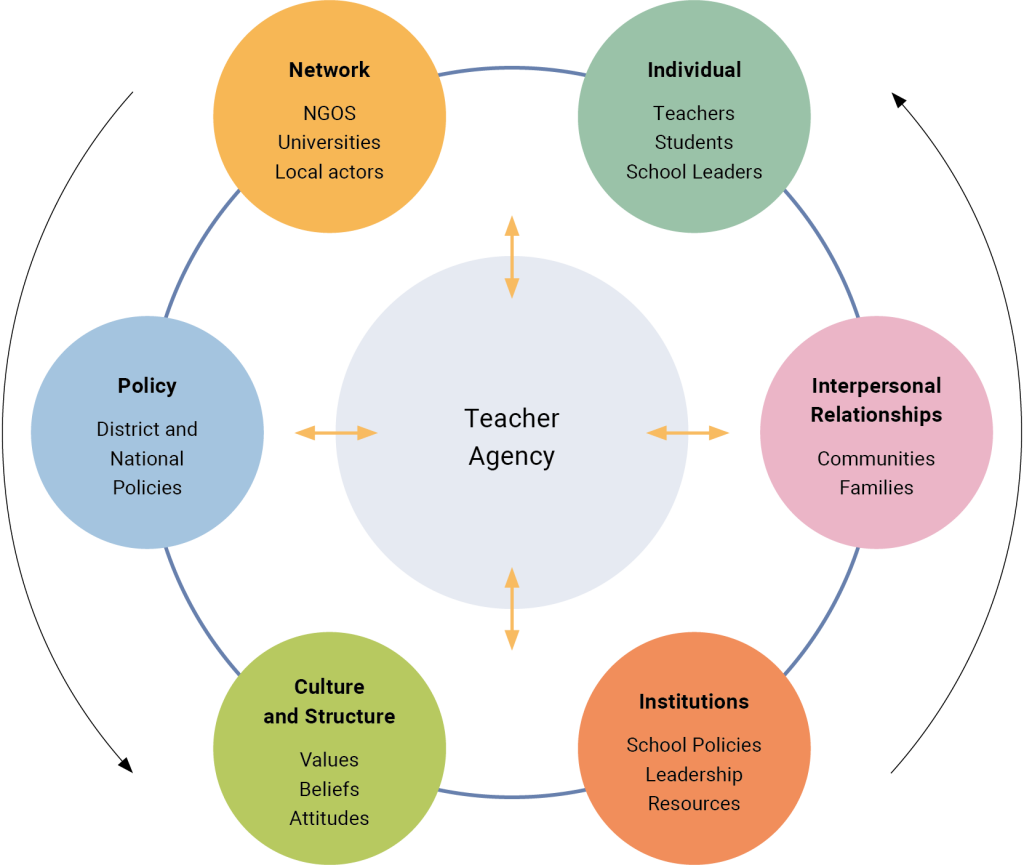

Building upon the established ecological models of education and agency (Bronfrenbrenner, 1994; Biesta & Tedder, 2007; Priestley et al., 2016), a revised framework is proposed, in order to reframe the model and diagram to better fit the context of teacher agency. Refraining from repeating a hierarchical structure, the current model illustrates the system in a nonlinear/non-hierarchical way, to account for the constant interaction between the actors in the system and the sites of action in various directions.

To achieve teacher agency, teachers remain the core actors, and their engagement with the whole system drives teacher agency. In addition to their systematically constructed capacity of agency, their impact on the ecosystem itself (through forming relations, groups, as advocates for more inclusive policies, and challenging the prejudices inherent in the culture), can reshape the whole system. However, teachers are not the only actors in our model that function in the individual domain. Students and school leaders can also be taken into consideration in the individual domain whose iterational, practical-evaluative and projective elements of agency shapes teacher agency in the ecosystem. For example, a school leader’s projective value on inclusive classrooms may enable teachers’ understanding of inclusion and consequently may build autonomy in the school system which directly contributes to teacher agency. On the other hand, students’ various personal histories, identities, values, and discourse may also foster teachers’ vision for an inclusive classroom and may cause teachers to reflect on their own values and identities. Therefore, the individual site of agency as not being restricted to teachers’ themselves, is the core of teacher agency. Importantly, the ripple effects of individual agency has similar repercussions on other actors within the ecosystem?

Figure 3: An illustration of the ecological model of teacher agency developed by the authors.

The illustration shows the words ‘Teacher Agency’, with a circle around, divided into six parts which say ‘Individual’, ‘Interpersonal Relationships’, ‘Institutions’, ‘Culture and Structure’, ‘Policy’ and ‘Network’. There are arrows around the circle to indicate movement, and there are arrows inside the circle pointing towards the words ‘Teacher Agency’.

Interpersonal Relationships

Aside from the individual, interpersonal relationships are defined as another actor which shapes agency. The web of relationships and engagement between the actors in the individual level (such as colleagues, students, school leaders, and support staff) acts as another sociocultural factor reframing, enabling or hindering teacher agency. Beyond this site, there is the institutional domain where school policies, leadership and resources available may shape how agency is perceived and practised. This site also links to the practical-evaluative elements of agency heavily by fostering or hindering the teachers capability to act.

Institutions

As a teacher, it is important to engage in conversation with your school leader or department head. School leaders are an important asset for teacher agency as they can provide the autonomy teachers need to enact their agency. Sometimes, school leaders are not aware of the needs of teachers, so it is important to advise them if there are areas which could benefit from improvement or change? This may also help to frame your ambitions in line with the school vision or societal needs. School leaders might look upon student teachers and early career teachers as people who still have a lot to learn. While this is true, early career teachers are also assets who may bring new perspectives and ideas to the school. Knowledge of the organisation culture, beliefs and structure to navigate their environment is also important. Kelchtermans (2019) labels this micropolitical literacy as it allows teachers a degree of freedom for actions and decision making which may impact on their learners. The organisation structure, restrictive as it may be, is not a one-way interaction. Therefore, it helps to dive into the organisational structure of your school and find out how it might be possible to make changes.

Network

Taking one step into the larger social structures, in areas Bronfenbrenner (1994) refers to as exosystem and macrosystem, we see sites of network, policy, and culture and structure. In our model, we identify the site of the network where NGOs, local organisations, universities that interact with the school and the teachers themselves, play an important role in achieving teacher agency. An NGO working on teacher empowerment or a university project, may help teachers to act upon their visions, and inspire and develop more inclusive approaches can greatly affect teacher agency. In this site, through interactions and experiences , teachers may even transform their understanding of agency and inclusion, and influence their teaching practices.

Policies

Beyond the network domain, there are educational policies at the district, state, and national levels that also have a profound impact on teacher agency and inclusion which may also shape the level of interaction inside the network around the school ecosystem. For example, a ministry of education may enforce prescriptive practices, form centralistic and rigid hierarchical interactions; therefore limiting the area of network, institutions, relationships, and individuals.

At the outermost layer, the culture of the society involves the values, beliefs, and attitudes within the school and the broader society. A culture promoting values such as inclusivity and autonomy is essential for enhancing teacher agency. So let’s start with what can be done. How can we achieve and nurture teacher agency in this complex web of relationships and interactions? We can start by talking a little about the core, the individual, the teachers themselves and what they can do to support their own agency?

Culture and Structure

The cultural and structural aspect of teacher agency concerns societal beliefs about teachers and the importance placed on them in policy. If policies are too hierarchical and seek to control the role of teachers, this would limit one’s agency. As some scholars have stated , teachers should not be role-takers, they should be role-makers. Teachers’ roles need to be viewed beyond that of implementers of policies. To be agentic here would mean teachers need to critically think about how a particular policy affects the inclusion of children. Teacher agency needs to be seen as an integral part of the profession, and structures need to ensure teachers are not working in isolation and instead make room for collective agency (as seen in CoP).

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Think about a recent situation in which you experienced teacher agency. Try to analyse it through the teacher agency model (iterational, practical-evaluative, projective).

- Think about your school’s structural, cultural, material dimensions. How can you achieve agency within this context?

- How does collaboration with peers and/or colleagues support teacher agency and promote inclusion? Make concrete examples.

- Can you think about situations that may limit or inhibit the achievement of agency? What can you do?

- Do you believe that you can always have agency, or can you think of a situation where you would have no agency? Discuss in groups.

- How can you be an agent of change for inclusion in your own practice?

Literature

- The word internship is used in this chapter to indicate that student teachers are involved in schools during the teacher education program. Depending on the (national) context, these internships can be highly integrated into the regular curriculum of teacher education or stand alone. Internships may also be known as placements. ↵

About the authors

name: Sara Baroni

Sara Baroni is Doctor of Research in Pedagogy and Didactics and primary school teacher. She is interested in wellbeing and equity at school, education in emergency situations, teacher reflective practices and inclusive education. She is part of different research groups in Italy and abroad.

name: Rhianna Murphy

Rhianna is a former primary school teacher with international teaching experience. She has a background in educational research, with a focus on curriculum-making and teacher agency. She has also worked on a range of small scale research projects with British Educational Research Association (BERA) and has experience lecturing on a range of teacher education courses.

name: Madhusudhan Ramesh

Madhusudhan Ramesh is an assistant professor in inclusive education. He heads a PG diploma programme in Inclusive Education designed for mid-career educators. His research interests include teacher agency, inclusive pedagogy, teacher professional development, and children’s experiences of difference and disability.

name: Günalp Turan

Günalp Turan is an NGO professional and an educator with a focus on communities of practice and teacher empowerment. He has a BA in language education and has taken graduate studies in cultural studies. He has been managing and advising national and international projects and organizations on inclusive education, critical thinking, community building, and andragogy.

name: Tamara van Woezik

Dr. Tamara van Woezik is assistant professor in teacher education with a focus on affective learning processes. She coordinates and teaches courses about pedagogy and teacher professionalisation. Her research focuses on sense of belonging, inclusion and autonomy-support using qualitative and arts-based methods.