Section 1: Developing Inclusive Educators

Understanding Yourself as an Inclusive Teacher – Teacher Professional Identity Development

Ann-Kathrin Arndt; Beausetha Juhetha Bruwer; Sarah Volknant; and Zhicheng Huang

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“I am a teacher who, as a learner, experienced difficulties in school. I left primary school unable to read and write properly due to dyslexia and my disadvantaged background. In secondary school, I was placed in intervention groups, which restricted my access to the mainstream curriculum. To pass my exams, I had to study at the local library because I did not have internet access at home. I chose to become a teacher to gain a better understanding of the decisions my teachers made about my educational path.”

Rhianna Murphy

Initial questions

In this chapter, you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is Teacher Professional Identity Development (TPID)?

- Why do we need it to promote more inclusive education?

- How to develop and support TPID in times of change?

- How can intersectional perspectives contribute to TPID?

Introduction to Topic

Teacher Professional Identity Development (TPID) is a multifaceted concept that varies across countries and subject areas. To discuss TPID, it is essential to clarify several key terms. Teacher Professional Identity (TPI) refers to the recognition of teachers as professionals, similar to other fields such as medicine or engineering. Teacher Professional Development (TPD) involves continuously enhancing a teacher’s subject knowledge and teaching skills. Going beyond TPD, TPID focuses on the broader development of a teacher’s identity including their roles, values, and social influence.

TPID involves the ongoing construction of a teacher’s professional self-image and role within the educational environment (Pishghadam et al., 2022). This process includes continuous learning, research, and collaboration, emphasising the teacher’s potential for growth and development. It requires teachers to be lifelong learners, researchers, and collaborators who are deeply invested in maintaining their professional image (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2012). TPID enhances a teacher’s professional knowledge and skills and fosters an understanding of educational philosophies, pedagogical approaches, and societal expectations. Through ongoing practice and reflection, teachers refine their professional identities, roles, and educational philosophies.

While TPD focuses on the enhancement of professional knowledge and skills, TPID is centred on the development of professional identity and self-awareness. Both concepts are interconnected, complementing each other to support a teacher’s professional growth. TPD typically follows a series of stages, from novice to expert, as teachers gain experience and expertise. TPID, however, is a continuous and dynamic process, influenced by personal experiences, educational backgrounds, and social contexts. Teachers can develop their professional identity through reflective practice, participation in professional learning communities, and mentorship. In relation to being an inclusive teacher, TPID plays a vital role in fostering a deep sense of self-awareness, empathy, and commitment to diversity, which enhances a teacher’s ability to create an inclusive and supportive learning environment for all learners.

This chapter will explore TPID by providing key theoretical concepts and offering multiple opportunities for reflection on your own journey, your personal educational and national context, and your identity as a teacher. It will delve into questions such as: What influences our perception of a good teacher and why? How is TPID shaped during times of change, and how does it vary across countries due to cultural, social, and historical factors? By looking at the educational approaches of China, Namibia, and Germany, the chapter will provide insights into how each of these countries addresses inclusion. Additionally, the chapter will encourage reflection on how privileges and disadvantages impact educational journeys and teacher identities. Finally, it will examine how we can cultivate sensitivity to the intersectional experiences of learners, fostering a more inclusive and equitable approach to teaching.

Key aspects

Teacher Professional Identity Development as a Constant Process and Multidimensional Concept

Teacher professional identity is regarded “as dynamic, multifaceted, negotiated, and co-constructed, the processes of identity negotiation being highly individual, but also shaped by teachers’ socio-professional institutional environments” (Edwards & Burns, 2016: 735). The professional identity is of key importance for teaching (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). According to Sachs (2005) teacher professional identity provides a framework for teachers to help them formulate ideas on how to be, act and understand their work, as well as construct their own ideas on their place in society.

When focusing on the development of teacher professional identity, you can either look at the individual level or refer to the collective (‘teachers’). Based on previous research and ongoing discussions, both developing individual and collective teacher professional identity is considered as relevant (Suarez & McGrath, 2022). Collective teacher identity refers to a “shared understanding of professional communities” (Suarez & McGarth, 2022: 10) and encompasses a feeling of belonging (Davey, 2013). Teacher professional identity (development) has received increased attention in the last decades. Nevertheless, important questions, especially on collective teacher professional identity (development), remain (Suarez & McGrath, 2022: 10). Regarding the individual and collective level, teacher professional identity (development) is of great importance for pre-service and in-service teacher education (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019).

How can we understand individual and collective teacher professional identity development? Looking at professional standards or education policy documents might suggest that there is only one way to develop teacher professional identity. However, Mockler (2020: 323f.) emphasises that there are multiple ways to develop teacher professional identity. How can we define the development of teacher professional identity to capture this? According to Mockler (2020: 324), developing teacher professional identity is “in a nutshell, (…) about understanding your own orientation to education, to schooling, to your learners, and to your subject area, and connecting and aligning these to your practice.” Therefore, “a robust teacher professional identity can help you align ‘who I am’ with ‘what I do’” (ibid.).

Let us pause and reflect.

Think about Mockler’s (2020) ‘in a nutshell’ definition: What is important for your understanding of education, schooling, your (future) learners, and your subject area? If you have already had practical experiences within schools: How did this understanding align to your teaching practice?

Take some time to reflect on aligning ‘who I am’ with ‘what I do’ from your perspective: What comes to your mind? You could create a MindMap or visualisation of your choice to further reflect on this.

Earlier notions, for example, by Huberman (1989), referred to several consecutive “stages of the ‘life cycle’ of the teacher” (Mockler, 2020: 324). However, Mockler (2011: 324) emphasises that teacher professional identity development is “less linear and more complex” (Mockler, 2011: 324). At the same time, different understandings based on different theoretical frameworks of teacher professional identity (development) prevail. In this context, Akkerman and Meijer (2011: 308) draw on the theory of dialogical self in psychology to understand teacher professional identity “as both unitary and multiple, both continuous and discontinuous, and both individual and social.”

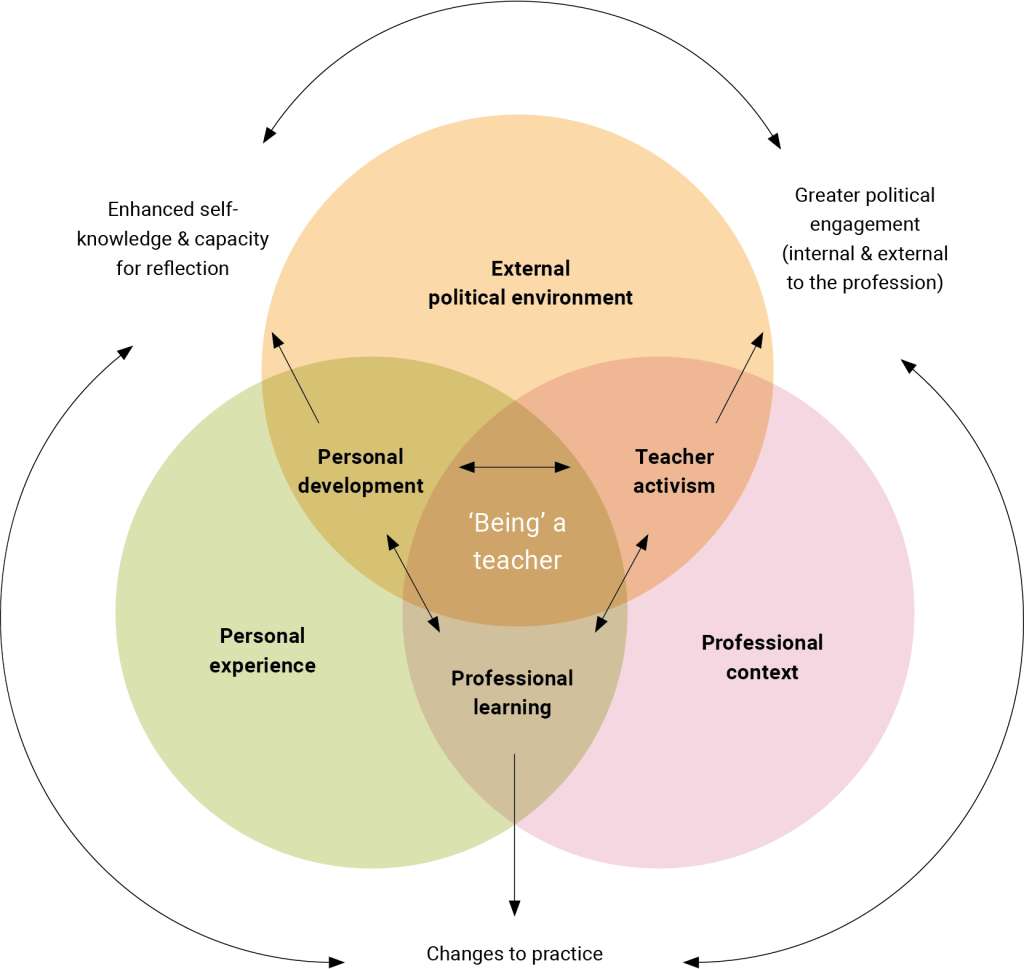

While, by way of example, this gives you a glimpse into ongoing discussions on how to understand and conceptualise teacher professional identity, different understandings and models converge in the understanding of teacher professional identity as a multifaceted or multidimensional concept. Based on previous work (Mockler, 2011), Mockler (2020: 325) refers to the “confluence of personal, professional and political dimensions.”

Figure 1: “Becoming and ‘being’ a teacher”

As Reeves (2018: 98) highlights with regard to teacher identity work in neoliberal contexts, (re)negotiating teacher professional identity is situated within the “multiple, differentially-powered voices that conflict and converge around what makes for ‘good’ teaching and teachers.” Looking at teacher professional identity in the era of accountability, Buchanan (2014: 700) notes that “20 years of standardisation, tight coupling, and ubiquitous testing practices have begun reshaping the nature of many teachers’ professional identities.” This is of particular importance as tensions between inclusive education and standardisation and accountability may arise, for instance concerning the understanding of student achievement. At the same time, Ainscow et al. (2006) indicate that, on school level, the standards agenda and inclusive education are intertwined. Based on their research, they underline the need to “support teachers to take greater control over their own development” (Ainscow et al., 2006: 306).

Let us pause and reflect.

What are – conflicting as well as converging – ideas about ‘good’ teaching and teachers? How could these ideas, as well as the broader political situation, influence teacher professional identity? What tensions may arise regarding understanding yourself as an inclusive teacher?

Overall, it becomes clear that teacher professional identity is not a static concept. This is of particular importance when looking at teacher professional identity development in times of change.

Teacher Professional Identity Development in Times of Change

The professional profile of teachers has always been dynamic, adapting to meet the needs of educational systems influenced by societal shifts and advancements in learning processes (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). Given teachers’ significant impact on learner outcomes, society and educational systems place high and varied expectations on their roles, particularly during periods of transformation. In a world marked by instability and uncertainty, the complexities within educational systems are amplified, necessitating strategic and policy approaches that emphasise innovation and flexibility over traditional methods (Suarez & McGrath, 2022).

Teachers are responsible for fostering children’s intellectual development and preparing future generations to face new challenges (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). In this capacity they play a pivotal role in the modernisation of society. Therefore, the goals and outcomes of education must align with societal changes. School and system reforms, whether focused on national or global objectives, must adapt to these shifts by redefining teachers’ roles and competencies. This requires ongoing professional development (see chapter on → Professional Development) and lifelong learning programs, allowing teachers to keep their knowledge and skills up to date in response to evolving societal demands, demands integral to the development and sustainability of teacher identity (Thomas, 2019).

As the professional landscape for teachers continues to evolve, a strong professional identity becomes increasingly important. This identity, which includes teachers’ beliefs and perceptions of their roles, is vital for navigating these rising expectations and ensuring the delivery of high-quality education (Suarez & McGrath, 2022). To gain a clearer understanding of the contextual shifts that can challenge the role of a teacher and influence the development of their professional identity, this chapter will explore examples of changes that may be unexpected within the teaching profession.

The implementation of Inclusive Education

The role of teachers is dynamic in that it constantly adapts to the changing demands of education systems as it responds to societal shifts and developments in learning methods (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). A pivotal transformation in educational science occurred in the 1970’s when the focus moved from a segregated education system to one that promotes inclusive education, welcoming every child. The importance of inclusive education for all learners, both with and without special needs, has been well established. It represents a worldview where fundamental education is accessible to everyone, ensuring full participation, membership, and civic rights. Integrating learners with diverse abilities and cultural backgrounds into the same classrooms symbolises societal cohesion and integration, highlighting the broader societal value of heterogeneity in education beyond just academic outcomes (Galkienė, 2014).

UNESCO (2005) defines inclusive education by highlighting four key principles: Inclusion is an ongoing process aimed at continuously improving responses to diversity within the learning environment, it involves the continuous identification and removal of barriers to learning, it focuses on the participation and achievement of all learners in educational settings, and it places particular emphasis on groups of learners who may be at risk of marginalisation, exclusion, or underachievement. These principles highlight that educational systems constantly change, necessitating ongoing efforts to provide effective education for every learner (Zimba, Möwes & Victor, 2018).

A study done by Galkienė (2014) exploring the socio-educational characteristics that define the professional identity of teachers in the context of inclusive education shows that both learners and teachers highlight the significance of establishing a supportive and individualised learning environment that encourages participation from all learners. Learners appreciate teachers who exhibit empathy, understanding, and the ability to connect personally, valuing those who maintain a balance between being both demanding and caring (Galkienė, 2014). Teachers reflect on the need to build strong personal relationships with learners, recognising the importance of understanding each learner’s uniqueness and interpersonal differences. They also highlight the necessity of continuous professional development, creativity in organising the educational process, and the ability to motivate and support learners to achieve success (Galkienė, 2014). Thus, developing a teacher’s professional identity in the context of inclusive education requires ongoing adaptation to the multiplicity of learners, shaped by the teacher’s capacity to understand and embrace these differences. Teachers cultivate their professional identity through continuous reflection on their practices and by striving to enhance their skills and knowledge to ensure the success of every learner in an inclusive environment.

Unforeseen social change

As the teaching profession continues to evolve, marked by significant disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of cultivating a strong professional identity has become increasingly apparent (Suarez & McGrath, 2022). The pandemic posed unprecedented challenges, requiring teachers to rapidly adapt to new demands and environments. This adaptation included developing innovative teaching methods and utilisingnew online communication strategies with learners and colleagues. Balancing the pastoral care of their learners with their own professional and personal challenges profoundly impacted teachers’ self-perception, emotions, and overall performance (Bacova & Turner, 2023).

The sudden closure of schools worldwide due to COVID-19 forced teachers to swiftly transition to virtual instruction to meet the needs of learners and families. Teachers adapted to new teaching modalities overnight, often working harder than before while managing their own children’s education at home. They faced difficulties in ensuring learner engagement, particularly for those without reliable internet access. The pandemic underscored the essential role of teachers and their significant impact on learners’ lives (Jones & Kessler, 2020). Before the pandemic, there was already a strong emphasis on the crucial role of teachers in supporting the academic, social, and emotional well-being of learners. Teachers build their professional identities around these discourses, which emphasise care and impact as central to their roles (Jones & Kessler, 2020).

Bacova and Turner (2023) emphasise the importance of open vulnerability in shaping teachers’ professional identity. During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers navigated an emotional journey from anxiety and self-doubt to a reaffirmation of their roles as caring professionals, often driven by positive feedback from learners, colleagues, and communities. Despite sometimes opposing institutional rules, teachers found pride in their autonomous decisions, reinforcing their self-image as compassionate educators (Bacova & Turner, 2023). Their vulnerability encompassed empathy, accountability, and a commitment to helping learners through the social and economic challenges. This approach also extended to supporting colleagues’ well-being and professional growth. Reflecting on these experiences was found to be cathartic, helping teachers gain a deeper understanding of themselves and the future challenges they may face.

The Era of Technology

In the digital age, the role of teachers has expanded significantly, with their responsibilities constantly changing. Teachers are no longer just sources of information, they also serve as role models and mentors, shaping a society that is in constant flux (Avidov-Ungar & Forkosh-Baruch, 2018; Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). Traditionally, teacher identity was defined by the necessary competencies and knowledge, such as pedagogical skills and subject expertise. This traditional view underscores the importance of evaluation and ongoing professional development (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019). As educational needs and scientific advancements have progressed, teachers’ roles have shifted from simply delivering knowledge to facilitating learning, providing guidance, support, and values education. This evolution calls for training that covers not just teaching skills but also interpersonal, communicative, and Information Communication Technology (ICT) competencies. Thus, teachers’ professional identity involves understanding changing roles and acquiring relevant skills and knowledge (Martínez-de-la-Hidalga & Villardón-Gallego, 2019).

Such a role change occurred with the COVID-19 outbreak that forced educational institutions to implement extensive changes within weeks, shifting teaching to various online platforms that were unfamiliar to many teachers. Online teaching that goes beyond merely supplementing traditional methods requires teachers to re-evaluate their core beliefs about teaching and learning, as well as their roles. Many teachers were left unsupported and untrained to manage the transition to a fully technology-mediated environment, where policies and practices differ significantly from face-to-face settings. Consequently, teachers’ professional identities can be impacted, as teachers can feel vulnerable when long-standing principles and practices are challenged by new policies or expectations (El-Soussi, 2022).

The COVID-19 outbreak enforced giant steps to adapting education to the 21st-century requirements, essential for adopting innovative pedagogy. This involves implementing new educational approaches to prepare learners better for modern challenges. Innovative pedagogy consists of planned educational activities, introducing new ideas to enhance learning through interaction, ideally using project-based learning focused on real-life problems (Avidov-Ungar & Forkosh-Baruch, 2018). Curricula then needs to be developed by teachers who have 21st-century skills, focusing on learners’ interests and future skills. This includes integrating ICT to support knowledge-based teaching, active learning, and diverse resources. The concept of “quality pedagogy in an innovative environment” according to Avidov-Ungar and Forkosh-Baruch (2018), highlights the dynamic relationship between pedagogy and evolving learning contexts. Innovation in pedagogy may not always involve radical changes but can be seen as a gradual and relative process.

According to Steel (2009), as cited by El-Soussi (2022), teacher beliefs are often implicit and complex, potentially serving as either an obstacle to change or facilitator of effective practices. Integrating technology into daily teaching is challenging, as even technologically proficient teachers may not recognise its pedagogical value. Teachers whose pedagogical beliefs do not align with technology use are likely to avoid it or use it in ways that do not fit their teaching philosophy. Conversely, teachers whose beliefs align with technology tend to be more successful in adopting it in their teaching (El-Soussi, 2022). Thus, positive attitudes and beliefs about the value and utility of technology, with proficiency in ICT, encourage the acceptance and use of innovative technology-based teaching methods. Consequently, how teachers develop their professional identity effects the advancement of pedagogical changes and reforms (Avidov-Ungar & Forkosh-Baruch, 2018).

Teacher Professional Identity Development in Times of Change involves teachers adapting and evolving their professional selves in response to shifts in the educational landscape. This process includes reflecting on their roles, values, and practices, particularly during significant changes like introducing new inclusive practices, adopting new technologies, adjusting to educational policy shifts, or facing unexpected challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers continually redefine their professional identity to meet new demands and to ensure they can effectively support their learners’ learning and well-being.

Let us pause and reflect.

Changing teacher professional identity within inclusive education in different international contexts

Inclusive education is a global priority, but its implementation varies widely across countries and is influenced by cultural, social, and historical contexts. By examining the approaches of China, Namibia, and Germany, you can develop a deeper understanding of how diverse systems address inclusion. This highlights the successes, challenges, and opportunities in creating educational environments that cater to all learners, particularly those with special needs. The goal is for you to critically reflect on how professional development, teacher preparation, and societal attitudes shape inclusive practices. Grasping these dynamics can be significant for Teacher Professional Identity Development, as it enables educators to consider and adapt strategies from different contexts to effectively address local challenges.

Let us pause and reflect.

By exploring the strategies employed in China, Namibia, and Germany, you can ask yourself the following questions:

- What are the key challenges and successes in implementing inclusive education in each context?

- How does professional development differ across these countries?

- What elements do you recognise in your own country or context, and how do those elements help or hinder inclusive education?

- How do cultural and societal contexts influence the perception and practice of inclusion?

Inclusive Education in China

In China, there is a strong tradition of emphasising Teacher Professional Development (TPD) in teacher education, with future teachers studying their main subject for four years, encompassing both educational theory and practical teaching experience. After graduation, subject specialisation is a key part of a teacher’s identity, particularly in primary and secondary schools, where teachers focus on a single subject such as mathematics, Chinese, or English. This contrasts with some other countries, where primary school teachers may handle multiple subjects.

TPD in China is an ongoing process that helps new teachers quickly develop their subject-specific teaching skills. Various strategies support this growth, including mentoring by experienced teachers, participation in instructional and research groups, observing other teachers, and receiving feedback on teaching effectiveness. Teacher promotion in China follows a structured hierarchy linked to both professional development and salary increases, ranging from new teachers to expert master teachers.

However, when it comes to inclusive education, TPD alone is not enough. Teachers also need to engage in Teacher Professional Identity Development (TPID) to fully understand and implement inclusive education. While inclusive education is still in its early stages in many parts of China, cities like Shanghai have begun integrating learners with special needs into mainstream classrooms. Despite these efforts, challenges remain as learners with special needs are often exempt from academic exams, leading to a focus on learners without special needs due to teacher evaluations being based on learner performance.

Inclusive education in China is deeply connected to the reform of special education, which for over a century has segregated learners with special needs into special schools. By the late 1980’s, China began transitioning to a more integrated system, moving learners with special needs from special schools into regular classrooms. By 2003, the majority of special education learners were learning in regular schools, though this shift has been met with mixed success. Many regular school teachers lack the training to effectively manage classrooms that include learners with special needs, and some reforms have been superficial, without a true change in mindset.

In recent years, the Chinese government has shown a commitment to inclusive education. Following the 2015 UNESCO Education Forum and the Education 2030 agenda, China has introduced policies to promote inclusive and equitable quality education. Scholars and experts in China have been instrumental in advancing research and practices in inclusive education, establishing centres for studies, and developing experimental projects in several provinces.

While progress has been made, significant challenges remain, particularly in fostering an inclusive culture within schools and society, reforming curricula, and adequately preparing teachers. Despite the Chinese definition of inclusive education emphasising the inclusion of all learners and opposing discrimination (Huang Zhicheng, 2004), many teachers continue to overlook the needs of learners with disabilities. As the country moves forward in both TPD and TPID, achieving true inclusive education remains a long-term goal, though the path towards it is becoming clearer.

Inclusive Education in Namibia

Inclusive education in Namibia continues to evolve. After ratifying key commitments that support the inclusion of learners with special needs in general education and, ultimately, their integration into society (such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2006, the Salamanca Declaration of 1994, and the National Policy on Disability Revised Draft of 2011), Namibia has made significant strides by establishing an Education Sector Policy for Inclusive Education in 2013 (Chitiyo et al., 2016).

With this policy, teachers have received in-service training to better support learners with special needs in inclusive classrooms. Existing special schools, now referred to as resource schools under the Sector Policy on Inclusive Education, continue to play a vital role in equipping other teachers with specific strategies for teaching and supporting learners with special needs. However, more efforts are required to effectively address needs and allocate resources (Chitiyo et al., 2016).

Inclusive teaching requires teachers to recognise and value the diverse experiences and abilities of all learners, understanding that every learner’s potential is unlimited and embracing diversity. Although teachers generally show a commitment to inclusive education, their attitudes are often influenced by concerns about their readiness and the adequacy of the education system’s support. Effective inclusive teaching necessitates thorough training, adequate support, suitable working conditions, and the freedom to adapt teaching methods. Teachers must be responsible for offering diverse learning opportunities to all learners and continuously reflect on their practices to combat social biases and stereotypes (UNESCO, 2020).

High-quality training is crucial for inclusive teaching, addressing gaps in teachers’ knowledge about inclusive pedagogies, instructional techniques, classroom management, and multi-professional collaboration. This training must be practical, comprehensive, and include follow-up support to help teachers integrate new skills into their classroom practices. The challenge lies in moving beyond the traditional approach of preparing different teachers for different types of learners that can suppress diversity issues in teacher education and hinder effective inclusive teaching (UNESCO, 2020).

In Namibia, the Ministry of Education has raised concerns about the adequacy of pre-service training for inclusive and special education. According to Chitiyo et al. (2016), a 2013 educational needs assessment report identified a shortage of skilled professionals, particularly in special education, where specific training is lacking. While some inclusive education training is provided, it is insufficient to meet the needs of learners with special needs. Therefore, specialised training and ongoing professional development are essential to better equip teachers and enhance education quality for these learners.

A study by Mokaleng and Möwes (2020) indicates that teachers in a particular region in Namibia view supportive leadership as crucial for the success of inclusive education, emphasising the vital role school leaders play in providing necessary support. Without this support, inclusive policies are at risk of failing. The study further highlights the need for inclusive leadership to implement effective educational policies and programs. Many teachers feel unsupported, leading to negative attitudes towards inclusive education, often linked to insufficient knowledge, skills, training, and support. In addition, the study points out that large class sizes are perceived as a significant challenge to inclusive education in Namibia, with many teachers feeling overwhelmed and unable to meet the needs of all learners effectively. Teachers acknowledge that their attitudes are critical to the success of inclusive education, and negative attitudes are often associated with inadequate training and skills. Many also believe that inclusive education places excessive demands on them, likely due to a lack of knowledge and support, contributing to feelings of being overwhelmed. Thus, negative attitudes that often arise from a lack of support are identified as a major barrier to successfully implementing inclusive education (Mokaleng & Möwes, 2020).

The majority of teachers in a study by Chitiyo et al. (2016) emphasised the importance of professional development for teaching learners with special needs. This indicates that teachers in Namibia see the need for further training, suggesting that current pre-service education, which includes only a few courses on inclusive education, may not be enough to prepare them for supporting learners with special needs. However, the positive attitude toward professional development presents a valuable opportunity for Namibia to develop and implement robust special education training programs (Chitiyo et al., 2016). Research highlights a strong link between teacher professional development and overall education quality, particularly in relation to teachers’ beliefs, practices, and learner education. Effective professional development includes workshops, in-class coaching, team planning, action research, peer observation, and study groups. Namibia’s teacher development programs incorporate many of these elements, aligning with international best practices to enhance education quality (USAID/EQUIP1, 2006). However, significant work remains to be done in Namibia to ensure positive outcomes for all individuals with special needs.

Inclusive Education in Germany

In Germany, developments of inclusive education vary highly between the different federal states (Steinmetz et al., 2021), also regarding the persistence of special schools. As Powell et al. (2016: 244) conclude: “The German case, despite the legitimacy crisis of special schooling since ratification of the UN-CRPD, also reveals the remarkable path-dependent persistence of segregated and stratified schooling.” With great variance between the federal states, the extensive network of special schools largely remains (Bildungsbericht, 2024). This parallel system of special schooling limits learners’ opportunities for educational success by obtaining higher education qualifications (Bildungsbericht, 2024), as Goldan and Kemper (2020) have shown regarding learners with special educational needs in the field of learning difficulties.

In the last years, there have been increased links between inclusion and diversity in the German speaking discourses (Resch et al., 2020) and an increased emphasis on intersectional perspectives (Haas & Penkwitt, 2023). However, notions of inclusive education that focus on special educational needs or disabilities prevail (Löser & Werning, 2015). This leads to a missing link to migration pedagogy (Paraschou & Soremski, 2022) and disregards, for instance, intersections of language and disability (Mecheril & Natarajan, 2022). A narrow understanding of inclusive education as focused on special educational needs is reflected in a study on pre-service teachers’ understandings by Schaumburg et al. (2019).

With regard to the ways in which inclusive education is embedded in German teacher education programs, Blasse et al. (2023) emphasise that teacher education should enable pre-service teachers to perceive relations of power and domination and reflect on their own positioning within them. This would entail questioning their own beliefs, learning about the deconstruction of normative images and concepts of education as a core component of teacher education, and fostering critical reflection on power dynamics, differences, and inequalities as an essential part of developing a professional identity as a teacher. Paraschou and Soremski (2022) call for a broader understanding of inclusive education within educational science to ensure participation for everyone. The joint recommendations by the German Rectors’ Conference and the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the States in the Federal Republic of Germany (2015) on “Educating teachers to embrace diversity” state: “degree programs which lead to a teaching position in any type of school and at any level of schooling should prepare prospective teachers cooperatively to take a constructive and professional approach to diversity” (HRK & KMK, 2015: 2).

However, several challenges for teachers’ professional development and teacher education remain. The prevalence of a narrow understanding of inclusive education remains challenging regarding broader notions of diversity. For instance, Schreiter’s (2021: 72) analysis of module descriptions in initial teacher education for primary education indicates a lack of reference to sexual and gender diversity in teacher education programs. Furthermore, the strong tradition of special schooling in Germany is also reflected in teacher education programs, which mostly rely on a distinct model with separate programs for general and special education (Heinrich et al., 2013). At the same time, there are differences concerning the federal states and their respective guidelines and frameworks for teacher education. Hence, there are also examples for more integrated approaches to teacher education on the university level (Bielefeld University: Kottmann & Miller, 2022) or there have been changes on the federal state level following the UN-CRPD, for instance in the federal state of Berlin. Within separate tracks for special education, Junge’s (2020: 6) study on pre-service special education teachers reflects insecurities in the contexts of different situations in inclusive or special schools as well as the “need for students to be recognised as a ‘real’ teacher.” By way of example, this reflects the crucial role of teacher professional identity development in the context of changes as well as persistence in schools.

In recent years, professionalisation and teacher professional development regarding inclusive education and diversity have been the focus of several initiatives on both the federal and state level. Especially within the Quality Initiative for Teacher Education (Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) together with the federal states between 2015-2023. This initiative had the overall aim to improve the quality of teacher education, one major focus was placed on heterogeneity and inclusion. The projects included cross-sectional topics that considered curricula, methods, and teaching and learning arrangements in teacher education for all programs (BMBF, 2024). However, the end of funding places several challenges, for instance with regard to focusing on multidisciplinary collaboration as one important aspect for inclusive education (→ cross ref All means all chapters “Working within multidisciplinary teams” and “teacher agency”here) within teacher education programs (BMBF, 2023: 25).

By way of example, we reviewed teacher professional identity development in three contexts. At the same time, it is also important to engage with intersectional perspectives on teacher professional identity development, which will be addressed in the following section.

Teacher Professional Identity Development and Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a framework that examines how various aspects of social identities – for example, race, gender, disability, language, religious beliefs, or socioeconomic background – interconnect to create unique life experiences and overlapping systems of discrimination and disadvantage. In educational practice, an intersectional perspective raises awareness about the diverse realities and discriminations faced by individuals, highlighting the impact of power dynamics (for example, racism, ableism, sexism, etc.) in schools. The framework of intersectionality helps to analyse how different social categories and power structures interact, focusing on their inclusive and exclusive effects as well as the reproduction of inequalities (Budde 2018, Riegel 2016). The goal of intersectionality is to deconstruct power hierarchies and promote social justice by examining and challenging relations of difference and dominance, thus holding significant transformative potential (Lawrence and Nagashima 2020; Riegel 2016).

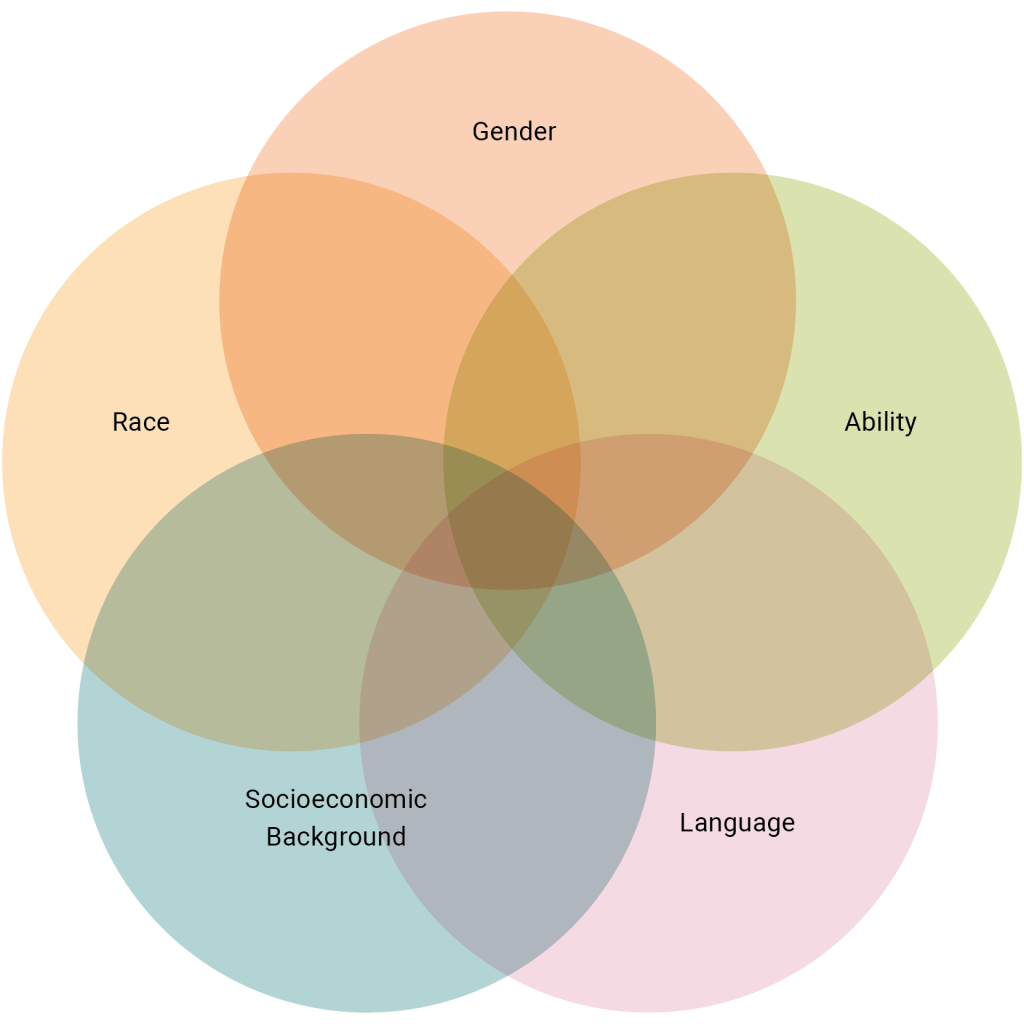

Figure 2: Intersecting Aspects of Identity

Figure 2 demonstrates how a selection of aspects of social identity might intersect with each other. It should be noted that this graphic includes only a selection; there are numerous other aspects that influence identity, such as religion, sexual identity, immigration status, and many more.

For pre-service and for in-service teachers, understanding intersectionality is crucial not only for appreciating the diverse identities of learners but also for recognising the importance of their own identities as educators (Pugach et al., 2019). An intersectional perspective allows pre-service teachers to reflect on their social positioning and on how it influences their teaching. It further helps to address and tackle inequalities that occur in every classroom (Boveda & Aronson, 2019). Pugach et al. (2019) undermine the need for an intersectional perspective on identity in teacher education:

“Probing the complexity of multiple identities not only can help [teacher] candidates understand how risk is amplified based on multiple jeopardies; doing so can also surface the multiple assets students bring – across identity markers – that can be marshalled toward learning” (Pugach et al., 2019: 214).

By adopting an intersectional perspective, an asset-based approach can be taken, which is central to inclusive teaching as it focuses on the strengths and potentials of learners rather than on their assumed deficits. Another aspect that underscores the need for an intersectional perspective when addressing teacher professional identity development is the often-encountered demographic mismatch between teachers and learners’ backgrounds. This mismatch can lead to problems in understanding learners, as well as prejudices and potential biases against them, which can hinder their educational experiences (Gershenson et al., 2016).

This section will closely examine these aspects, aiming to encourage self-reflection on intersectionality and the development of one’s identity as a teacher. After providing a brief historical context of intersectionality, we will explore the meaning of disadvantages and privileges in education as they relate to intersectionality. The section will also offer examples of intersecting teacher identities and include biographical insights.

Historic context of intersectionality

Disadvantages and Privileges in Education

When applying an intersectional perspective to TPID, it is crucial to consider issues of power and oppression, as they are inseparably linked to different aspects of identity. Questions of privilege and disadvantage are particularly useful when reflecting on both teacher and learner identities. While the term “privilege” may carry different meanings depending on the context, many people have an intuitive understanding of it as a common term. Black & Stone (2005) define privilege in relation to oppression, introducing the concept of social privilege. In this understanding, privilege is a special advantage that is context-dependent rather than universal. It is typically unearned and tied to a preferred social status or rank, benefiting those who possess it, often at the expense of others. Many times, individuals or groups holding privileges are unaware of them (ibid.). Since identities are shaped by multiple factors that intersect with privilege and disadvantage in different ways, it is essential to examine them through an intersectional lens. Black & Stone (2005) highlight this by discussing privilege within the context of socially constructed categories such as sexual orientation, socioeconomic status (SES), age, differing degrees of ability, and religious affiliation (ibid.). This list is not exhaustive; however, it underscores how multiple variables influence privilege. The challenges or possibilities that learners encounter due to being (de)privileged significantly shape their educational experiences.

For instance, Antoninis et al. (2020) took a closer look at the UNESCO 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report with a focus on inclusion and pointed out how disadvantages often intersect. It was observed that those most at risk of being excluded from education frequently face intersecting disadvantages related to “language, geographic location, gender, and ethnicity” (Antoninis et al., 2020: 105). Specifically, in at least 20 countries with available data, very few rural young women that live in poverty finish upper secondary school (ibid.). This example demonstrates the intersectional interaction of multiple factors, showing how limited access to resources – because of living in a rural area, having a low socioeconomic background, or living in poverty – interacts with linguistic background, age, and gender. In this way, an individual’s educational participation is hindered by multiple structural disadvantages, which can be traced back to various relations of power and domination, such as linguicism, adultism and sexism, as well as patriarchal and capitalist structures.

Another example of how privilege influences educational opportunities becomes evident when examining learners’ socioeconomic backgrounds. In Germany, only 32% of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families receive recommendation for higher-level academic tracks, compared to 78% of children from privileged families (Autor:innengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2024). Even when learners have the same academic performance and grades, still 59% of children from privileged families and only 51% of children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds receive such a recommendation (Autor:innengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2024).

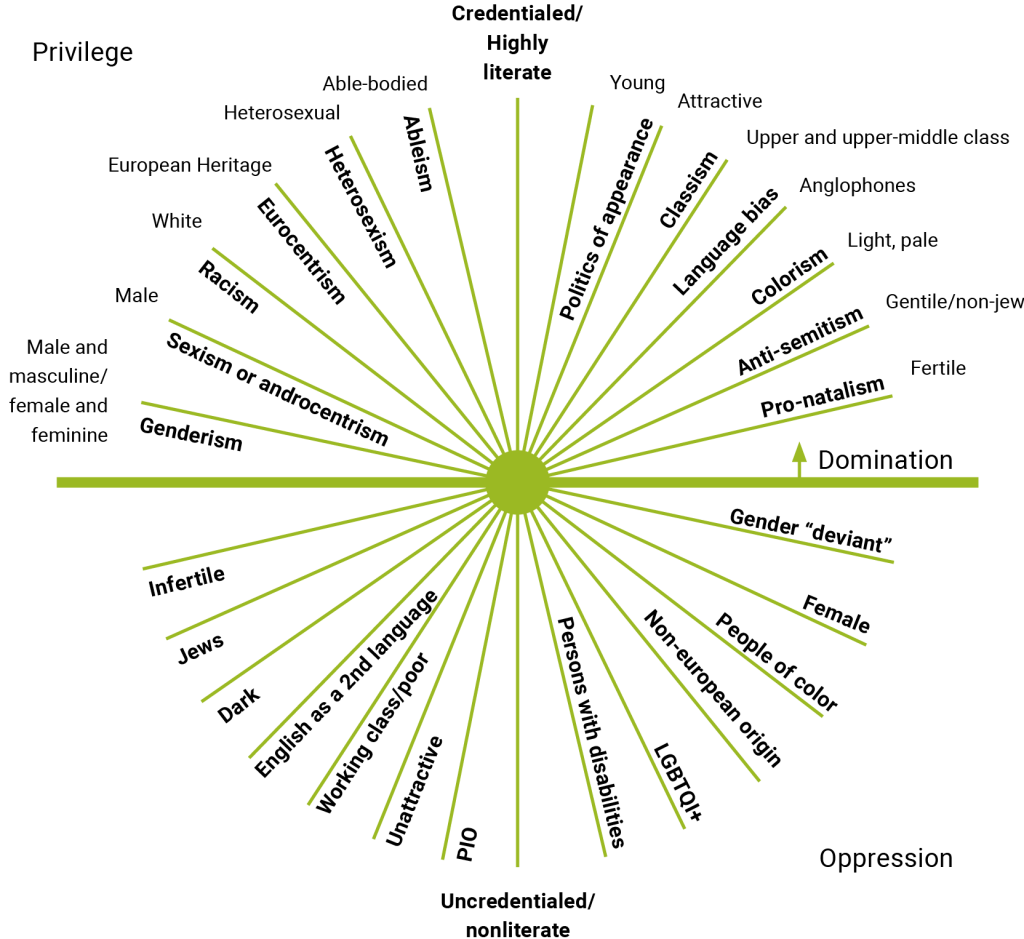

Figure 3: Intersecting axes of privilege, domination, and oppression

Figure 3 above illustrates how different social categories can be linked to privilege, oppression, and disadvantages. Each line represents a social category or aspect of identity, with one end associated with privilege and the other with oppression or domination. This representation wants to highlight how various aspects of identity can place individuals at different points on the privilege-oppression spectrum. It includes the concept of intersectionality by showing that these categories are interconnected and collectively shape a person’s overall experience in society. For example, a Black woman with disabilities experiences life not just as a woman, a Black person, or a person with disabilities, but as a combination of all these aspects, creating a unique experience that may simultaneously be influenced by power dynamics such as sexism, racism, and ableism (AWIS, 2018). However, it should be noted that aspects of privilege and oppression are context dependent. For example, Figure 3 views speakers of English as a second language as disadvantaged because it focuses on a U.S. context; however, the (de)privileging of languages depends on the specific context in which it occurs.

Let us pause and reflect.

Take a closer look at Figure 3. Try to think of three aspects of your identity that are especially important to you. Those aspects may or may not be represented in the figure. Write them down and reflect on how they have been connected to privileges, disadvantages, and oppression that you have experienced in your life.

Intersectional Teacher Identity

A teacher’s identity is essential not only for their development as educators but also in how they address inequalities and differences in educational settings. “Teacher identity can be broadly defined by how teachers make sense of themselves as professionals, by how they present themselves to others, and by the roles that they play in response to their disciplinary, social, cultural, and political contexts” (Maddamsetti, 2023: 2540). This implies that in the process of developing their professional teacher identity, teachers should be reflecting on the interplay between their self-concept and the external expectations and societal contexts they navigate.

An example of how experiences with self-concepts and external expectations may play out in a classroom is provided by Lawrence & Nagashima (2020). The authors explored the connections between identity, teaching practice, and university classroom interactions from an intersectional perspective by analysing personal written narratives through duo ethnography. They found that the intersection of gender, sexuality, race, and native-speaker status significantly impacted their professional identities as language teachers. For instance, one author reported that, as a bisexual Japanese woman living and working in the U.S., she experienced both sexualisation and fetishisation. While already facing fetishisation as an Asian woman, she chose to conceal her bisexuality to avoid further hyper sexualisation, given the false perceptions of sexuality often associated with bisexual women. The author further expresses that despite her desire to incorporate LGBTQ+ topics into her classroom, she hesitates because she fears learners might react with homophobia or indifference, which could negatively affect her personally (Lawrence & Nagashima, 2020). This example highlights how heteronormativity, sexism, and racism influence teachers’ decisions, in this particular case leading to the exclusion of certain topics from the curriculum.

Let us pause and reflect.

Can you think of a moment in your teaching practice where you felt a conflict between your self-concept as a teacher and the external expectations of your teaching environment? How did you navigate this tension, and what insights did you gain about your evolving professional identity?

Reflecting on one’s personal history is essential for understanding how individual experiences form professional identity. A teacher’s biography profoundly influences their beliefs and practices as an educator, with early experiences profoundly shaping their perception of what it means to be a teacher (Pajrares, 1992). Such reflection helps teachers link their personal histories to their teaching practices, offering valuable insights into their professional development. For example, Leckie & De Buser (2020) conducted a study that explored teachers’ autobiographies to investigate how intersectionality can act as a framework for professional growth. Their findings indicated that, through an intersectional perspective on their autobiographies, the participants were able to connect critical content with their own experiences in society and education. The study also revealed that even within a seemingly homogeneous group, teachers have encountered a variety of privileges and disadvantages in their biographies. By applying an intersectional lens to their own lives, teachers were able to better understand the experiences of diverse learners, despite differences in identity or social categories.

Let us pause and reflect.

Referring back to our example case, we can see that Rhianna’s self-understanding is deeply connected to and motivated by her own experiences at school. Reflecting on this from an intersectional perspective, considering the effective power structures and the privileged or deprived aspects of identity, we observe that her personal background resulted in hindrances on multiple levels. Her dyslexia, socioeconomic background, and limited access to resources intersected to shape her educational journey and created unique barriers and challenges. These challenges included being placed in intervention groups, which restricted Rhianna’s access to the mainstream curriculum and, consequently, to education in the same way as her peers. The decision to place her in a separate program was likely made by educators and administrators, significantly impacting her educational path and highlighting how power dynamics can influence the quality and direction of a learner’s education. These experiences inspired her to become a teacher, equipping her with the ability to empathise with learners facing similar challenges and informing her approach to teaching.

Let us pause and reflect.

Reflect on your own educational experiences and how they might have shaped your professional identity as a teacher.

- What aspects of your identity have led to advantages or disadvantages during your time at school?

- What barriers did you encounter (or not encounter) in your educational journey?

- Have these experiences influenced how you want to be as a teacher? If so, how?

Developing Intersectional Sensitivity

As demonstrated by Leckie & De Buser (2020), identifying and exploring various aspects of privilege and oppression and their interconnectedness can profoundly influence teaching practices. The authors further argue that reflecting on one’s own experiences is essential for understanding and shaping one’s role as a teacher (ibid.). Additionally, the adoption of an intersectional framework reveals that everyone, often unconsciously, internalises traits from oppressive ideologies. This realisation underscores the importance of understanding how oppression shapes our society and therefore influences institutions, including schools and other educational facilities. To effectively incorporate these insights into teaching, the concept of “intersectional sensitivity” can serve as a reference point. According to Volknant et al. (in press), intersectional sensitivity in pedagogical practice encompasses several key aspects. Primarily, it involves teachers developing the ability to identify the individual circumstances their learners are in and also to recognise the privileges and disadvantages accompanying them. This approach requires more than just knowledge and diagnostic skills; it demands a mindset and practical approach that prioritises an empathetic understanding of the challenges that learners face in their everyday lives. Furthermore, it calls for responsive actions that address these challenges, considering each learner’s individual biographical experiences (ibid.). To develop an identity as an intersectional sensitive teacher, the following points should be considered:

Knowing: Understanding the history and mechanisms of power and dominance, as well as inclusion and exclusion, particularly within the relevant context (for example, national, cultural, political, etc.).

Identifying: The ability to identify learners’ individual needs in relation to their intersecting aspects of identity, as well as the power structures, privileges, and disadvantages at play and how they manifest in the classroom. An intersectional framework (Boveda & Aronson 2019; Leckie & De Buser, 2020; Riegel, 2016) can assist in this identification process.

Acting: Taking responsive actions that address learners’ individual needs, continuously reflecting on one’s practices, beliefs, methods, and materials. This involves addressing critical or discriminatory actions that occur within the classroom, among staff, or in school organisational structures. It also encompasses engaging in ongoing professional development, for instance, by continuously participating in teacher education.

Intersectional sensitivity is central when considering TPID because it emphasises the ongoing reflective process educators must undergo to understand their roles and responsibilities within a diverse and complex society, thereby enabling meaningful inclusive teaching.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Reflect on the context of teacher professional identity in your country or context. What is the role of a teacher?

- What role do cultural and structural differences play in shaping teacher attitudes and professional development towards inclusive education, and how can these insights help create more effective training programs?

- Think about how you want to be as a teacher. Reflect on why including intersectional perspectives is crucial for your professional identity as a teacher and how it connects to your own identity, your learners’ identities, and societal power structures. Try to visualise those connections through a drawing, diagram, or a written reflection that helps you express these relationships.