Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

“Please, don´t sit on my shoulder” – From Neo-liberal to Emancipatory Perspectives: Shifting Landscapes in the Roles of Teaching and Personal Assistants

Danielle Farrel; Marie McLoughlin; Eileen Schwarzenberg; and Melanie Eilert

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

My Desire for Independence and the Need for Support: Finding the Right Balance

“Don’t sit on my shoulder”

“I am a wheelchair user. Increasingly, I have found that I need to balance the support I receive from my Personal Assistant (PA) with the need to build friendship in my own right. For example, on a recent night out for a colleague’s retirement, I required support to attend this event from my PA. Of course my PA was involved in some of the social interactions during the evening, but it was important for me to mix and interact with colleagues on my own. This is my preference, and I always make it clear when recruiting staff. It is important for me that my PA is present but not ‘sitting on my shoulder’. However, from the point of view of the PA, this can be hard to manage, especially if they are used to working with a variety of people who may have complex needs or if they are used to working in a residential environment and move to supporting someone to live independently in their own home.”

Dr Danielle Farrel, Managing Director Your Options Understood (Y.O.U.), UK

Initial questions

This chapter sets out to provide an overview of Teaching Assistants and Personal Assistants. In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is a Personal Assistant and Teaching Assistant?

- What roles and tasks does a Personal Assistant and Teaching Assistant undertake?

- How are they employed?

- What qualifications, education and training do they have?

- How can they positively influence social integration?

- How is the relationship with other professionals or the person they assist characterised?

Introduction to Topic

The purpose of this chapter is to examine the role of Personal Assistants (PAs) and Teacher Assistants (TAs) in supporting people with disabilities in their daily lives. Since 1994, Maher and Vickerman (2018) refer to the Salamanca Statement which “expressly entreated national governments to ‘adopt as a matter of law or policy the principle of inclusive education, enrolling all children in regular schools” (UNESCO). Since then, inclusion principles have been reinforced by a number of global and European policies such as the Dakar Statement (Maher & Vickerman, 2018) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2009) through Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education. Significantly, this topic is enshrined within the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD) which provides a comprehensive framework to protect and promote the rights of people with disabilities and highlights several key rights. Article 9 stipulates that measures should be put in place to ensure accessibility by removing barriers that hinder full participation in society for persons with disabilities. Article 19 requires the provision of appropriate support services, including personal assistance, to enable individuals with disabilities to live a full life in the community and exercise their autonomy. Finally, Article 24 recognises a right of access to persons with disabilities to education on an equal basis with others. Hence, the provision of inclusive education, with reasonable accommodations and supports, is necessary to facilitate the effective education of persons with additional needs (United Nations, 2006).

This chapter begins by providing a brief overview of the context for employing TAs and PAs. We then proceed to examine the role of TAs and PAs in supporting persons with disabilities in their daily lives and in educational settings. Next, we endeavour to define the roles, discuss associated terminology and provide an overview of the respective responsibilities associated with both roles. Additionally, we explore how teachers and assistants engage and interact with each other in various settings. Further, we discuss supports that are in place to help Personal/Teacher Assistants (P/TAs) and their employers as well as the influence P/TAs can have on peer relations and social integration. Finally, recommendations for the future are discussed.

At times, the topic is discussed within the context of a few specific countries namely, the UK (Scotland in particular), Ireland and Germany. Beside scientific contents, you will find in the chapter several case studies which illustrate the contents and provide a deeper insight into the perspective of the self-advocates. Most case studies were written by one of the authors of the chapter, Danielle Farell.

Description of structural disadvantages and how to address or prevent them

While there are several structural disadvantages, we have chosen two very significant disadvantages on the recommendation of self-advocates, both of which have received little attention in research so far. Firstly, we discuss the influence of TAs and PAs on social integration, and secondly we focus on the relationship between TAs and PAs.

Structural disadvantage 1: The Influence of TAs/PAs on Social Integration

Social integration of people with disabilities is limited. Many suffer from social exclusion and discrimination, despite the UNCRPD’s existence in many countries which supports/emphasises? greater participation. On the one hand, TAs and PAs can positively support people/pupils with disabilities to participate in social life, however, they can also influence social integration negatively (see Case Study 1). The term social integration has no single definition. Indeed, social integration, social inclusion and social participation are often used interchangeably while social integration as a term is variously defined (Koster et al., 2009).

In this section, we employ the definition from Stinson and Antia (1999) discusses the importance of social integration in relation to peer acceptance and friendship, and view peer interaction as an essential factor in social integration.

Social integration of students with TAs in regular classroom

In general, studies indicate that the social position of students with special needs is particularly poor when educated in a regular classroom. Often, they are less accepted and less popular than their classmates without special needs, and consequently make fewer friends (Banks, McCoy and Frawley, 2018; Saddler, 2014). It is important to notice that pupils with SEN are a heterogenous group. Therefore, peer relations can differ according to the type of special needs (Koster et al., 2009). Nevertheless, it is important to examine how social integration of students can be improved if a TA is involved.

Influence of a TA on social integration

We will now explore the influence of teaching assistants on social interaction. There is a paucity of research in this area and outcomes also vary across studies. Furthermore, previous research has primarily focused on the influence of TAs on academic achievement which generally suggests that TAs have a positive influence on students’ learning achievement (Farrell et al., 2010; Saddler, 2014). Research on increased social integration of students in Germany occurred through the promotion of social skills, peer contact and peer interaction (Jerosenko, 2019). Additionally, supporting social behaviour was seen to contribute to more social contacts (Schindler, 2019).

In contrast, however, Webster and de Boer (2021) contend that facilitating the inclusion of pupils with learning difficulties can reduce interactions with teachers and peers and create dependencies on TAs. Zauner and Zwosta (2014) studied the stigmatising effect of TAs on students in Germany and found that most teachers did not recognise such effects (62%) and failed to acknowledge the disturbance of other pupils by the presence of the TAs in the classroom (72%). However, a significant proportion still see some stigmatising effects or disturbances.

In terms of students with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities (PIMD), high-quality interactions are crucial for their quality of life (Haakma et al., 2021). Due to their profound special needs in terms of physical condition, mobility, health problems, sensory impairments and non-verbal language, one-to-one teaching assistance is increasingly important. Many PIMD students use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) and therefore their interaction with peers differ. In a single case study, Schwarzenberg, Melzer and Penczek (2016) found that peers often use several communication strategies to interact with the PIMD student who uses AAC. They accepted the student, and some made friends with the student. Additionally, Haakma et al. (2021) revealed that TAs tried to facilitate interactions between peers and PIMD students. For example, some TAs adjusted the student’s position by taking a student out of their wheelchair and placing them on the ground among a group of playing students. However, even if the TAs attempted to facilitate interactions between students with PIMD and peers, these interactions were often unsuccessful. This represents how difficult it is for TAs to initiate and influence peer interaction positively.

Negative Effects linked to Social Integration of Students with SEN and a TA

Several studies point to the negative effects linked to social integration of students with SEN. Giangreco et al. (2005) outline five negative effects: firstly, students with a TA are often seated apart from peers in a corner of a classroom; secondly, students become dependent on support from the TA and are unable to participate without the TA. Thirdly, TAs disturb peer interactions by establishing a physical or symbolic barrier for peers. Fourthly, the TA and the student have a very close relationship by virtue of doing everything together, hence other teachers and peers may be excluded. Finally, students feel stigmatised due to the continuous presence of the TA. Similar findings were identified by Sharma and Salend (2016) which found that TAs often taught SEN pupils separately in individual and small groups, thus spending less time in the classroom with fewer peer interactions. Furthermore, the constant presence of TAs and the delivery of separate instruction also limited student interactions. Students with a TA can be perceived by their peers as different and dependent, which can lead to stigmatisation. For example, Jerosenkos (2019) stated that the presence of TAs was increasing students’ dependence and impeding the child’s interactions with classmates.

How can TAs positively influence social integration?

In light of these findings, how can TAs positively influence peer interaction and social integration? Firstly, awareness of the roles and responsibilities of TAs in schools should be improved. This includes reflections on roles and responsibilities of TAs which may lead to shifts in responsibilities. Teams should reflect on whether a TA is needed in each situation and the benefit of TAs in specific situations (Giangreco et al., 2005). For instance, Highton (2017) interviewed six TAs and found that the frequency and intensity of peer interactions depended on how the assistants fulfilled their role and how they interacted with the students. If they act in a very dominant, instructive and regulatory way, interactions were prevented. If they acted as so-called “coaches” and offered support to help students in solving their conflicts themselves, peer interaction and friendships can develop over the long term.

In terms of participation, it is important to activate and strengthen the child’s voice. In other words, students themselves should be more involved in deciding what support they need. In the majority of the studies, teachers and assistants were interviewed whilst the student’s perspective was not considered. Schools need to establish a culture of collaboration within classrooms. Hence, strengthening collaboration between general and special educators, building capacity in general education, and increasing reliance on natural supports is recommended (Giangreco et al., 2005). In addition, natural support should be considered whereby peers can be more involved in supporting the disabled peer with a TA as peer supporters.

Finally, parental perspectives are examined in terms of how TAs may be best deployed for their children and if their views are consistent with the effective use of TAs in inclusive classrooms (Sharma and Salend, 2016). Parents should be asked why they want support for their child, and how best this support can be offered. These perspectives can then be considered in the deployment of TAs.

The Influence of Personal Assistants on Social Integration

A PA can support people with disabilities to participate in everyday life. However, this can lead to people with disabilities becoming dependent on the PA. and thereby precluding them from making friends and being part of a group (see Case 5). For example, Wadensten and Ahlström (2009) found that PAs can enable the establishment of close relationships, social interaction, company, and a community spirit through activities in, and outside, of the home. Some participants reported that their PAs have a social function where they felt they had new people to interact with and therefore felt less lonely. That said, PAs described “difficulties of being in a subordinate position” (Ahlström and Wadensten, 2012, p. 112) even if they expressed satisfaction with their work. Some reported feeling lonely and missed the work community. They also felt that they have a lack of control in unstructured work and experienced stress with too much responsibility. The majority reported a need for more education (Ahlström and Wadensten, 2012).

How can the balance between support and independence be strengthened? Toward cooperative models of living and working together

When a person with disabilities relies on support from a PA to assist them with social interactions, it is crucial that the PA enables the disabled person to develop their own identity and build their own relationships. The PA’s role is fundamental in this instance, particularly if the disabled person has a high level of support needs. Nevertheless, the PA’s role must be balanced by enabling the supported person to spend time with their peers, family members and colleagues, and allowing others to build a relationship with the person who requires support, as opposed to building a relationship with them and their PA.

Maskos (2014) criticises that in today’s discourse of self-determination, an emancipatory perspective is missing, in which disability, illness and dying are an integral part of life. People are dependent on each other, in varying degrees, including people with disabilities. Therefore, it is necessary to consider how life can be shaped with, and in, these dependencies, rather than requiring that all dependencies be overcome. More cooperative models of living and working together are needed.

Structural disadvantage 2: Relationships between teachers and TAs and between a self-employer and a PA

Relationships play an important role in dealing with the support of people/students with disabilities through PAs or TAs. Relationships, even if professional in nature, are rarely conflict-free, and various factors, such as different roles and responsibilities, influence relationships. In the field of education, there are several professional relationships, such as the relationship between teachers and TAs. The central question is how to work together in a team? The same question can be applied to the relationship between a person with a disability and a PA.

Team Relationships between Teachers and TAs

Many professionals, such as social workers, therapeutic professionals (e.g., speech therapists, learning therapists), as well as TAs are increasingly working in tandem with teachers in schools (Serke and Streese, 2022). The research indicates there is a need for teachers to improve their work with TAs (Jackson et al., 2021). In an international systematic review of 26 studies, Jackson (2021) examines the teachers’ perspective of their work with TAs and identified four key themes including; roles and responsibilities, planning and pedagogy, leadership, and interpersonal relationships.

Firstly, the role of a TA, and the expectations associated with the role, cause tensions in TA-teacher relationships. According to Butt and Lowe (2012), teachers and TAs perceive the role differently, and in some instances, teachers are not certain about what level of responsibility TAs should be given.

A second issue, related to the respective roles, concerns the nature of the working relationship between SNAs and teachers. This has been described in terms of collaboration, partnership and teamwork which implies joint planning and problem solving (Logan, 2006). Yet, there seems to be a lack of awareness around the real benefits associated with collaborative planning and indeed in most jurisdictions, time for such planning is often limited (Jackson et al., 2021). Interestingly, Logan’s research found that 70% of SNAs perceived that teachers did in fact involve them in planning, whilst by comparison, only 53% of teachers felt they involved the SNA in planning. That said, 85% of teachers felt it was appropriate to do so. Relatedly, teachers are often challenged in understanding whether or not a TA has the capability to assume a pedagogical role, which is often associated with the level of qualification the TA holds. In sum, it could be construed that the provision of time, and awareness building around how and why to engage in planning, may support the development of enhanced collaborative partnership towards better overall provision for the children in their care.

A third theme associated with relationships is that of teacher leadership. Teachers need to assume a leadership role but often lack the requisite knowledge and skill. Jackson et al. (2021) concludes that: “Teachers need to view themselves as leaders of TAs. They should be involved in recruitment, supervision, and training of TAs yet they need time and supervisory training themselves to learn and hone this skill” (p. 83).

Finally, it has been found that interpersonal relationships between TAs and teachers have been influenced by differences in status, working conditions (Jardi et al., 2022), and school type (Blatchford et al., 2009). Degrees of co-operation are also associated with certainty about one’s own role, which in turn affects levels of job satisfaction for TAs (Blatchford et al., 2009).

How can the relationship between a TA and teachers be supported?

Jardí et al. (2022) examined how effective interpersonal partnerships are built. Findings show that having a close affinity with each other, open communication, a sense of belonging, professional compatibility, interpersonal treatment, and trust are equally important. Contextual factors, such as employment conditions, supervision, and administrative support, were less important. They concluded that: “Building a partnership is reported to be a long-term pathway, it is a process that should be purposefully fostered and adjusted through time” (Jardi et al., 2022, p. 8). TAs and teachers need time to get to know and understand each other to ensure collaborative and supportive attitudes. A sense of belonging and the perception of being welcomed are more important for TAs than for teachers. Above all, TAs want to feel respected and valued by teachers.

A recurring theme in the literature is the promotion of effective teamwork. Three specific models have been developed around this (Vincett, Cremin and Thomas, 2005). The Room Management Model (RMM) requires that all adults in the room are given a clear role; the Zoning Model refers to a system of classroom management where adults take responsibility for different zones in the classroom. In the Reflective Teamwork Model (RTM), the participants receive training in skills based on teamwork, with a particular emphasis on effective communication. Additionally, the teacher and the TA are asked to plan and review their teaching sessions in equal collaboration daily (Vincett et al., 2005). According to O’Brien (2010), the RTMl was favoured by participants as it improved communication, developed more positive working relationships, and supported role clarification.

Jackson et al. (2021) concluded that “teachers who are aware of the delineation between their roles and responsibilities and those of TAs may be more likely to implement more equitable and inclusive models of student support” (p. 76). Clearly, all of these point to the need for a redefinition of tasks, roles and responsibilities in addition to a strengthening of structures towards the enhancement of cooperation and collaboration (Serke and Streese, 2022).

Potential challenges of changing roles

A potential challenge for students leaving school is the transition from teaching assistant to personal assistant. Here, it is important to consider how students can be accompanied during the role change and, if necessary, how this can be prepared for in the long term at school by consciously addressing the process and gradually giving the student more responsibility for guiding the assistant. A gradual transition from assisting the teacher to assisting the pupil can help prepare young people with disabilities for their role as employers.

Relationship between PAs and self-employed / Person with disability – towards more awareness

Despite the fact that PAs play an important role in the lives of people with disabilities, the relationship between PAs and self-employed persons with disabilities is delicate. “There exists, therefore, a disjunction between the ideal image of PA as a commercial relationship free from emotional dilemmas, and a disparate literature charting moral dilemmas and interpersonal conflict within PA relationships” (Porter et al., 2022, p. 632). Porter et al. (2022) reported challenges that PAs faced under three different headings: 1) practical trouble, for example in working conditions and management style; 2) personal trouble, for instance, conflicts because of different personalities or different values; and 3) proximal trouble, for example socio-spatial proximity of a PA. A major area of tension is where the person with a disability is both an employer and an expert in his or her own life, whilst at the same time, is existentially dependent on his or her employees. For example, it can be difficult for the person with disabilities to criticise their PA if, at the same time, they are existentially dependent on the PA. The PA has an intimate insight into the life of the person giving the work, while at the same time being an employee. This tension between the employer’s dependence on the employee must always be reflected upon and dealt with professionally (Kasper and Zuber, 2023).

PAs must be aware that their place of work is often within a private home. People with disabilities and their families may feel uncomfortable with having strangers in their home (Porter et al., 2022). Conflicts can arise due to different attitudes and perceptions. In this context, PAs need, among other things, a high degree of attentiveness and considerable practice in expressing their own opinion but only when requested and in a restrained manner. In addition, they should always critically reflect on their own behaviour with regard to possible tendencies to influence the person receiving assistance. Furthermore, PAs should always clarify and become aware of their current role (friend, assistant, advisor, ambassador, bridge builder) (Kasper and Zuber, 2023).

Key aspects

Historical Context for the Establishment of Personal Assistants and Teaching Assistants

Personal Assistants – Independent Living Movement

The establishment of the PA role can be traced back to the so-called “Independent Living Movement” in the 1960s and 1970s. In the USA and the UK, many people advocated for people with disabilities to live independent lives within the community and not in institutions. Experts and organisations in the field of special education and rehabilitation have been partially replaced by a new paradigm, which was developed by people with disabilities themselves (Barnes, 2014). The movement started in the early 1980s in Germany with the slogan of “Selbstbestimmt-Leben-Bewegung” (self-determined living movement) (Maskos, 2014). In many countries, this movement changed views on people with disabilities from a medical or individual model to one of a social model of disability (Barnes, 2014). In contrast to the medical model, where disability is seen as an individual phenomenon, which is addressed with medical measures (Waldschmidt, 2005), the social model of disability is seen as a ‘social problem’ (Barnes, 2014). Hence, disability is understood as a social construct, created through discrimination and oppression. This shifts the focus to society, rather than the individual (Degener, 2016).

Another model which emerged following the establishment of the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is the human rights model of disability (Degener, 2016). In this model, human rights cannot be invalidated by disability, but are taken for granted. This contrasts with the social model, in that human rights could be partially denied through attribution (Degener 2016). Personal assistance is well linked to the human rights model of disability underpinned by the UNCRPD as it empowers people with disabilities to live independently and receive community-based support. One primary goal of the Independent Living Movement was deinstitutionalisation, i.e., the dissolution of institutions for people with disabilities and the provision of assistance to enable people with disabilities to exercise more control over their own lives, and live life to the fullest. PAs, which emerged from this campaign, are perceived as a necessity to support people with disabilities, affording them the same choices and control in their everyday lives that people without disabilities take for granted (Maskos, 2014).

With this movement, there has been an undeniable shift in the landscape of social care resulting in an upsurge in demand for PAs as more people with disabilities now live in their own homes. Notwithstanding this trend, significant work has still to be done as many people with disabilities still live in institutions (Maskos, 2014). To compound matters, the UK and many other countries experienced a recruitment crisis (following the Covid-19 pandemic) across all areas of social care. This has precipitated the need for closer examination of the current provision of services. Consequently, in recent years, the UK reviewed adult social care services. In England, this review was conducted under the Social Care Reform (Migration Advisory Committee, 2022) whilst the Scotland Government conducted the independent Adult Social Care review (Feely, 2021) aimed at the implementation of a National Care Service. Within this, there are plans for better working conditions for employees in Social Care, including PAs, which in turn may address the increasing demand for skilled people to fulfil these roles. In Ireland, a slower uptake with ‘personalisation’ is evident – this umbrella term is used to refer to people living with disability who now have choice and control around their support. In implementing this strategy, a similar approach is adopted in Scotland, whereby disabled individuals and families living with disability are afforded options on how to allocate and spend their budget. As a result, there has been an increase in demand for PAs. The same increase in demand for PAs emerged in Germany in 2016 when the so-called Bundesteilhabegesetz (BTHG) came into force. Up to 2023, four reform stages were implemented, which will fundamentally change the law for people with disabilities. The aim is to implement the UNCRPD to help people with disabilities to have more participation and individual self-determination. To this end, services are no longer institution-centred but person-centred (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2016).

Before proceeding, it is important to distinguish between special educational needs (SEN) and special education needs and disability. As the authors of this chapter are from Ireland, the UK and Germany, both terms are used. The former – SEN – is defined within Irish legislation to mean:

a person [who has]…, a restriction in the capacity […] to participate in and benefit from education on account of an enduring physical, sensory, mental health or learning disability, or any other condition which results in a person learning differently from a person without that condition and cognate words shall be construed accordingly; (Government of Ireland, 2004, p. 5)

In documentation from the UK, young people who have SEN may have a disability under the Equality Act 2010:

…a physical or mental impairment which has a long-term and substantial adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities’…[]…This definition includes sensory impairments such as those affecting sight or hearing, and long-term health conditions such as asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, and cancer. Children and young people with such conditions do not necessarily have SEN, but there is a significant overlap between disabled children and young people and those with SEN. Where a disabled child or young person requires special educational provision they will also be covered by the SEN definition” (DofE & DofH, 2015, p. 16).

In the UK, the term Special Educational Needs and Disability is typically used as an umbrella term, however, SEN usually applies to children with a specific learning difficulty while a child with SEND may also have a diagnosed disability.

The Emergence of Teaching/Special Needs Assistants in Education

In recent years, the increase in numbers of Special Needs Assistants (SNAs) coupled with the provision of greater training opportunities, demonstrates the importance attached to the development of this role. Between 1992 and 1996, there was a 56% increase in the number of staff working in primary schools in England (Groom & Rose, 2005). Concurrently, a commitment to inclusive policies in England resulted in an increase in the number of pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) or Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) attending mainstream schools (Maher & Vikerman, 2018). A similar development can also be observed in Germany. Since Germany signed up to the UNCRPD in 2009, inclusive education has been established in many federal states. Pupils with special needs attend the mainstream school and, within this context, require support. This support is offered by an increasing number of TAs (Sansour & Bernhard, 2018). However, in Germany, the number of hours of special education teachers per student has decreased over the last 30 years, while the number of hours provided by teaching assistants has increased dramatically. Previously the education authority traditionally financed teaching hours, whereas teaching assistants are now financed through the social welfare budget.

The role of the TAs has been identified as critical in the promotion of inclusive schooling. Many students may not have been effectively managed in educational settings without the support of these essential professionals. Indeed, Zhao, Rose and Shevlin (2021) found that in Ireland, SNAs were considered crucial in delivering more inclusive learning environments. However, whilst studies related to the German context highlight the importance of teaching assistants, focus was placed predominantly on the characteristics of and structures for Teaching Assistants within individual federal states, as opposed to examining the topic across states (Lübeck & Demmer, 2022).

Terminology and Definition: Personal Assistant and Teaching Assistant

In the field of disability, the term ‘assistance’ has become a contested term in recent years. However, most are not aware of what assistance actually means in the context of people with disabilities (Leuenberger, 2023). Across Europe, the terminology used to describe individuals who assist people with additional needs varies from country to country, and sometimes from state to state. Broadly speaking, there are two distinct terms, that is a PA and a TA.

Defining Personal Assistance

A PA is a clearly defined term. The UN Committee (2017) clarifies this: “Personal assistance means person-directed/user-directed human support for a person with disabilities and is an instrument for self-determined living” (UNCRPD, 2017, p. ?). Personal assistance is not simply another word in the multitude of terms used to describe assistance services, but is closely linked to the enabling of a self-determined life (Leuenberger, 2023). Therefore, personal assistance has been defined by members of the independent living movement as “a tool which allows for independent living” (Mladenov, 2020, p. 2). In Germany and other German speaking countries, the terms “Assistenz” (Assistance) and “Persönliche Assistenz” (Personal Assistant) are used (Leuenberger, 2023). In line with Irish policy, a personal assistant is someone “employed by the person with a disability to enable them to live an independent life. The personal assistant provides assistance, at the discretion and direction of the person with the disability, thus promoting choice and control for the person with the disability to live independently” (Buchanan, 2014, p. 12). These services are generally provided to persons with physical and sensory disabilities. In contrast, persons with disabilities over the age of 65 access the Home Support Service which provides home-based supports, such as cleaning, cooking and sometimes personal care.

Defining Teacher Assistants

TA is generally used to describe support staff who assist pupils in schools. This may also include higher-level teaching assistants (Saddler, 2014), while further afield, in Australia and USA, TAs are also referred to as paraprofessionals, teacher aides, and paraeducators (Sharma & Salend, 2016).

In the United Kingdom, TAs in educational settings can also be referred to as Learning Support Assistants (LSAs) (Groom & Rose, 2005). In Ireland, TAs are known as SNAs and provide schools with extra staff to support children who have additional and significant care needs. Such assistance facilitates pupils’ attendance at school, fosters the development of independent living skills and reduces disruption to teaching time for all pupils (DES, 2014). In a comprehensive review of the role of SNAs, the National Council for Special Education (NCSE) in Ireland recommended that SNAs “be re-named as Inclusion Support Assistants to reflect their role in promoting independence and inclusion” (NCSE, 2018, p.7). This indicates a shift from special needs terminology which some students find difficult. Zhao, Rose and Shevlin (2021) confirm this redesignation in the terminology, and highlight their specific care role which differs to the role and duties of the teacher.

It is important to note that these terms may vary from country to country and indeed across regions, depending on local practices and policies. For example, in Germany, terms differ across federal states. Defining a job title is still problematic today, as there are no precise legal regulations on their roles. In addition to the term Schulbegleiter* (school companion), terms such as “Schulassistenz” (school assistance), “Integrationshelfer*in” (integration aide), and “Schulbegleiter*in” (school aide) are used. These terms refer to individuals who support students with disabilities or additional needs in inclusive classrooms (Dworschak, 2010). Progressive states (such as Bremen) are currently testing solutions in which school assistants are not assigned to individual children, but rather are available to the class as a pool offer (Vanier, 2024) and subsequently support different children as required.

Responsibilities Carried out by Personal Assistants

PAs are individuals who support a person with a disability to live an independent life (Self-Directed Support Scotland, 2021). The role of the PA emerged from the Independent Living Movement (see Chapter 4.1.1 and 5.1). The person with disabilities directs how tasks should be completed by the PA. A PA does not generally assist with making decisions or choices but rather assists the person with a disability in meeting identified outcomes. The key difference between a PA and a paid carer/support worker is that the PA is accountable to their person with disability who is their employer, who, in turn, is responsible for the welfare and safety of the PA, as well as their conditions of employment (Self-Directed Support Scotland, 2021). The case below provides an insight into the role of a PA:

Case Study 1: My Role as a Personal Assistant

“It’s a job that is as varied and interesting as the human experience can be”

I’ve worked as a PA for a few different people over several years, and each job is as individual as that person is. Essentially my job is to support a person with disabilities to live independently. I support them with whatever they might need, anything from attending birthday parties to after-school clubs, holidays or work trips, support to run a business, to perform in theatres, do homework, write an article, or just to get on with their daily lives at home. The job can involve varying degrees of personal assistance, for example, assistance with mobility aids, communication aids or feeding devices, and it requires a high level of trust and respect. It’s a job that is as varied and interesting as the human experience can be, and I feel very lucky to be able to do it.

Maria Herbert-Liew, Personal Assistant, Scotland

Responsibilities Carried out by Teacher Assistants

The introduction of additional in-class support has been hailed as the single most important factor in enabling pupils with SEN to be integrated and maintained in mainstream classrooms (Groom and Rose, 2005). Zhao, Rose and Shevlin (2021) explored the role of SNAs within Irish schools and found that SNAs were highly valued in the education system. They contend that SNAs availability has greatly enabled schools to create flexible, inclusive learning environments for children. However, the authors also stress the complex and multi-dimensional nature of the role. More generally, they describe the multitude of responsibilities comprising physical caretaking, organisational support, managing behaviour, promoting independence, collaboration between SNAs, teachers and other school professionals. In Ireland, the Department of Education (DES) lists the primary care needs provided by a SNA which comprise: assistance with severe communication difficulties; assistive technology, feeding, toileting, general hygiene, mobility, orientation, moving and lifting of children; supervision; administration of medicine; care needs associated with specific medical conditions or requiring frequent interventions or withdrawal from the classroom (DES, 2014). Secondary care tasks carried out by SNAs include: assistance with the preparation and tidying of workspaces; the development and review of plans; monitoring pupils attendance and care needs; enabling access to therapy or psycho-educational programmes; preparation of school files and materials, liaising with class teachers and other teachers; attending meetings and attendance at out-of-school activities (DES, 2014). Blatchford et al. (2009) also identified tasks related to TAs or SNAs, which include: support for teachers and/or the curriculum; direct learning support for pupils; direct pastoral support for pupils; indirect support for pupils and support for school administration, communication and environmental (p. 76). Similarly, Giangreco et al., (2005) refer to the variety of valued roles carried out by TAs, for example, “clerical tasks; follow-up instruction or homework assistance; supervision in group settings (e.g., cafeteria, playground, bus boarding); assisting learners with personal care needs (e.g., bathroom use, eating, dressing and facilitating social skills, peer interactions, and positive behaviour support plans” (p. 29). Whilst educational instruction should be the responsibility of trained teachers, TAs often assume primary instructional roles which can foster improved academic, behavioural and social outcomes for students when they are appropriately trained and supervised. It is evident that the TA role is broad, varied and dependent on the needs of the specific needs of the pupil. The example below is a testimony from a TA:

Case Study 2: My Role as a Teacher Assistant

“He is now able to cope with everyday school life independently”

My name is Simone Manger, I am a nursery teacher and I worked for four years as a Teaching Assistant for a student with special educational needs (SEN). The company I applied for is a GmbH (limited liability company). Beside Teaching Assistants, they employ personal assistants but they offer teaching assistant positions, family support and inclusive holiday support. My student was nine years old when we met first and he went to the fourth class of a regular, mainstream school. My tasks were to offer the student structures, safety and individual support to get more independent. Together with the class teacher I planned my tasks and responsibilities collaboratively. To avoid stigmatisation by his fellow students, we figured out that I can support other students as well if he doesn’t need my support. Another important aspect of my work was the cooperation with the student’s parents. They had high expectations for their son’s learning. So, I had to clearly distinguish myself and repeatedly demand understanding for their son’s individual development. As the close relationship with my student was an essential part of my pedagogical work, it was always a challenge for my student when I was replaced by colleagues he did not know in case of my illness. He often refused to cooperate on such days and conflict with his classmates increased. During the COVID-19 pandemic, my student was supported by another colleague, as I had to homeschool my own children. This colleague spent five hours a day at my student’s home, accompanied him during the video conferences and supported him with the subsequent tasks. After the lockdown my student went back to school and I then took over again. I observed that the intensive home schooling had led to a significant improvement in his grades on the one hand, but on the other hand he was less independent in solving tasks and problems on his own. Central aspects of my work were then to support him in regaining his independence at school and the social integration into the class after the pandemic. Within the four years as a school support teacher, I was able to support my student in (further) developing his academic and social skills to the extent that he is now able to cope with everyday school life independently.

Simone Manger, Teaching Assistant, Germany

Employment

Employment of TAs and PAs is organised according to the specific country and differs regarding work situation, qualifications and payment. In this section we focus first on the employment of PAs and then describe employment of TAs.

Employment of Personal Assistants

There are two ways PAs in Germany are employed. Firstly, the PA is employed by a care service/company (see Case 3). The care service/company organises and pays the assistant. Secondly, PAs are employed on the basis of ‘direct payments’. People with disabilities become ‘employers’ or ‘contractors’ who either directly recruit, hire and manage their personal assistants, or do so through the mediation of independent service providers (Mladenov, 2020). The employment is possible due to the so-called “Persönliches Budget” (“Personal budget”). This concept of assistance is intended to express a different understanding of professional help, and the relationship between beneficiaries and service providers is thus redefined (Konrad, 2019). Which service provider pays depends on the personal situation and on the specific assistance required. For example, if you need work assistance, the Federal Employment Agency (BA) or the Integration Office can pay the costs. As in many professions, the salary depends on the respective employer (Konrad, 2019).

In the UK, if an individual requiring support decides to employ PAs directly, this is usually undertaken through Direct Payment. This is one of four options of Self-Directed Support in Scotland, and is also an option in the south of the UK. Although opting for a Direct Payment gives disabled people and families more choice and control around their support, it also brings with it all the responsibilities of an employer, such as recruitment, ongoing training and managing staff. Payroll companies are also set up across the majority of the local authorities in Scotland to assist PA employers with payroll. Some of these organisations may also be able to assist with the training and recruitment of PAs, however, the supported person is still the employer. The phrase ‘employed by’ in the Irish context, means that the service user has full control over the PA. Typically, however, service users avail of allocated funding to employ a PA through service providers (Carroll & McCoy, 2022).

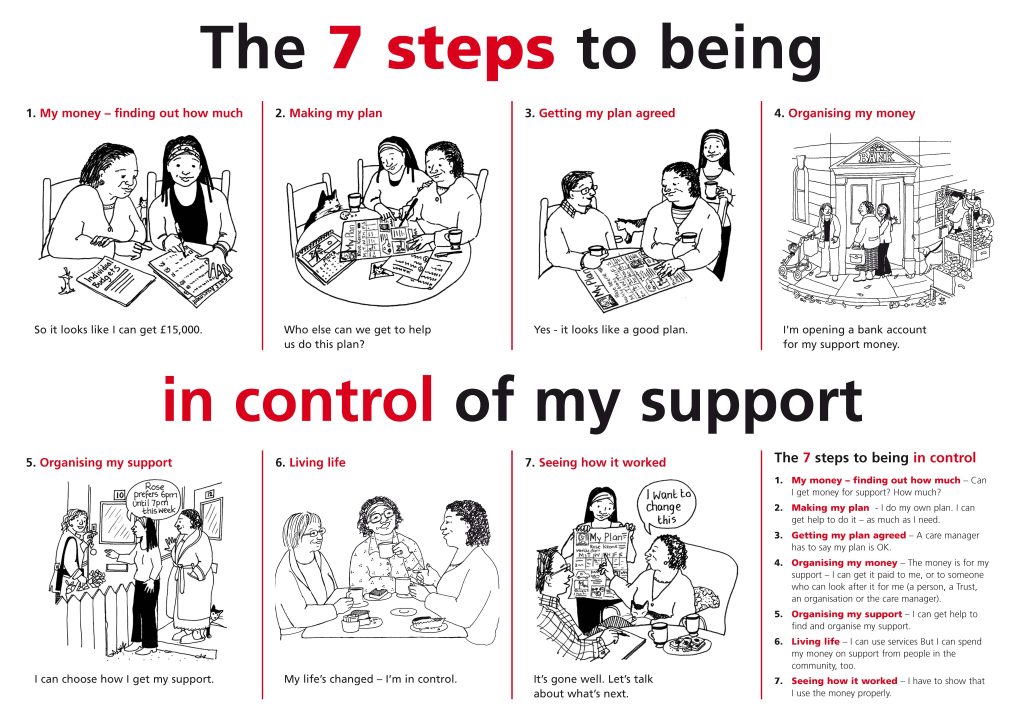

The figure below illustrates how support is organised via Direct Payment in seven steps (in Control, 2020).

Figure 1: Information about self-directed support

Danielle and Maria outline seven steps in building cooperation towards support (see Case 3 below).

Case Study 3: How I am Employed as a PA

“She still has all the choice and control around her support and how it’s provided”

My name is Maria and I am employed by Enable to support Danielle. Enable is one of a small number of provider organisations that work within a PA structure. The beauty of being supported by an organisation working within a PA structure is that they recruit a team specifically around each person and their support needs. Danielle is involved in the interview process and in deciding whether staff are successful in gaining a post in her team. She still has all the choice and control around her support and how it’s provided but she doesn’t have the responsibility of being an employer and managing her PA team. Most provider organisations across the UK, who deliver Social Care services do not have this structure and instead simply send staff where and when they are needed. As a result of this approach, it is often the case that the supported person does not receive continuity of care.

Danielle Farrel, Managing Director Your Options Understood (Y.O.U.) and Maria Herbert-Liew, Personal Assistant, Scotland

Employment of Teaching Assistants

In Germany, the employment of TAs varies across federal states. In a study from 2022, Idel and Korff found that TAs in the federal state of Bremen were employed by different private providers/agencies (such as private providers, foundations, and welfare associations) who all compete for business. There is no legal regulation for the control of these providers consequently costs vary. TAs view their employment situation as precarious, nevertheless, they hold high intrinsic motivation, as extrinsic motivation factors, such as better payment and promotion opportunities, do not exist (Kißgen et al., 2016).

In Ireland, the NCSE “is responsible, through its network of local Special Educational Needs Officers (SENOs) for allocating SNAs to schools to support children with special educational needs” (DES, 2014, p. 13). An SNA’s contract of employment is with the managerial authority of the school in which they are employed. An SNA’s salary is paid directly by the DES, and prior to the appointment of an SNA, applications are made by the school to the NCSE. Allocations are considered on the basis of an assessment made by a relevant professional who reports that a pupil has a significant medical, physical or sensory impairment. Under certain circumstances, SNA support may be allocated where the care needs relate to behaviour. SNAs are allocated to schools and not individual pupils, and are therefore a school-based resource. Schools manage their allocation by targeting the children in greatest need and exercise autonomy and flexibility in order to provide for the care needs of identified children as, and when, those needs arise. SNA allocations are also time bound and specifically linked to the Personal Pupil Plan (PPP). The allocation may be made initially for a maximum period of three years, but is subject to annual review and a full reassessment of their care needs at the end of this period. As the care needs in schools change, SNA positions may avail of a redundancy scheme operated by the DES (DES, 2021).

In the UK, TAs are employed directly by the school, the local authority, or academy trusts. The average salary for a TA starts at £14,000 per annum and more experienced TAs may earn up to £21,000 (National Careers Service UK). TAs are not generally assigned to a specific child, rather they may provide support fluidly across groups of pupils or only for particular lessons. Models of deployment reported were whole-class support; targeted in-class learning support; or targeted intervention delivery (Skipp and Hopwood, 2019).

Educational Training and Qualifications

As described previously, one major concern in the field of employment is educational training and qualifications of TAs and PAs. In this section we will describe education and training in different countries.

Education and Training of Teaching Assistants

It seems that a very heterogeneous group of people work as TAs. While some TAs have basic qualifications, others have little specialist training or qualifications. Sharma and Salend (2016) contend that TAs rarely receive adequate training and supervision. In Ireland, the minimum qualifications required for appointment to the post of SNA is either a FETAC Level 3 qualification on the National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ) or a minimum of three grade Ds in the Junior Certificate or equivalent (DES, 2021). Despite this, the NCSE states that training opportunities available to SNAs are insufficient. Additionally, although training for SNAs was deemed the responsibility of the Board of Management in schools, funding is not provided. The review concluded that whilst many undertook training at their own expense and in their own time, a generic programme should be available for all SNAs to address topics relevant to the role, along with customised programmes specific to the needs of certain children (NCSE, 2018).

Likewise no regional or national standards exist for TAs in Germany, despite evidence suggesting that high-quality education for children with special educational needs can only be implemented if professionals are appropriately qualified (Billerbeck, 2022). The granting of a TA is subject to varied pedagogical qualifications / or varies according to contexts? For example, if a child gets a TA in accordance with the SGB VII (Social Code Book VIII) of the Child and Youth Welfare Services, a qualification is necessary. However, this is not the case for a child or young person with a mental, physical or multiple disability according to SCB XII (Social Code Book XII) of the Social Welfare Services (Billerbeck, 2022). TAs with qualifications have, in general, a pedagogical, medical or nursing professional background whereas TAs with no qualifications may have experience in a range of working areas (Kißgen et al., 2016). The training rate in some federal states, such as Bavaria, Thuringia, as well as in the Lower Saxony/Hannover region is over 50%, even if no qualification is required. Dworschak and Markowetz (2010) emphasise the professionalisation of TAs and recommend further education and training.

In the UK, schools and local authorities set their own entry requirements. However, entrants into relevant courses usually require 2 or more General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSE) at Grades 9 to 3 or 4, or 5 GCSEs at Grades 9 to 4 or equivalent (National Careers Service, 2023). College qualifications at certificate level such as Supporting Teaching and Learning in Schools are available where persons interested may enter the role with a qualification in childcare or early years education. An alternative route is via a Teaching Assistant Advanced Apprenticeship.

Education and Training of Personal Assistants

In the UK, PAs and Support Workers who work for support providers differ in the level of formal qualifications required to fulfil the role. In the UK, staff working for a provider organisation are usually required to have at least a SVQ (Scottish Vocational Qualification) 2 or equivalent in Social Care. PAs are unlikely to be employed full-time and often work under zero-hour contracts. Furthermore, they are less likely to hold formal care qualifications – yet tend to earn more than their care worker counterparts Interestingly, some people with disabilities deliberately choose not to have assistants trained as care workers because they want assistants who act on the instructions of the person with disabilities and not on the basis of previous work experience in the healthcare sector.

Case Study 4: How I organise self-directed support and Personalised Budgets

“Promote my independence and my identity.”

My name is Dr Danielle Farrel and I am a Personal Assistant (PA) employer in Scotland. In order to assist with the recruitment of personal assistants, I receive financial support from the local authority based on an individual needs’ assessment. I have opted to use a mixed approach to budgeting for the support services I need. On the one hand, I can have a self-directed budget and on the other, I can access funding which is managed by the local authority (Scottish Government, 2013) to assist with the employment of personal assistants. In my personal and professional experience, a number of issues have become apparent to me when employing a PA. Firstly, I believe that qualities such as person-centredness, listening skills and respect for the need to assist me in living my life in the way I want to, are critical. My PAs need to have the ability to promote my independence and individual identity. In addition, my PA should help me in a positive manner to help me to reflect on and address my own identity without “sitting on my shoulder”. I continuously strive to advise my PA team of what support/s I require. In this regard, mutual respect is key and both parties should have a clear understanding of the expectations associated with the role. Formal qualifications aren’t necessarily a must. These qualities outweigh any formal qualification.

Dr Danielle Farrel, Managing Director Your Options Understood (Y.O.U.), Scotland

Conclusion and recommendations

Over the last few decades, views of disability have encompassed medical, social and, more recently, human rights approaches/perspectives? The human rights model has led to greater empowerment of people with disabilities encouraging a more independent and autonomous way of living. Relatedly, there has been an increase in demand for TAs and PAs and the corresponding rise in terms and labels suggests a need to re-define these roles to ones which accurately reflect their roles and responsibilities??

Similarly, with respect to responsibilities carried out by both TAs and PAs, evidence points to the challenge of balancing adequate support along with fostering independence, choice and autonomy. With regard to teacher and TA responsibilities, other concerns remain. Most notable of which is the regular blurring of responsibilities, which requires careful navigation and most importantly, the need for professional dialogue between all parties. Moreover, there needs to be an awareness of collaborative teamwork. Teachers and TAs should discuss, and clearly define, their roles and responsibilities, respect each other as experts and take time for teamwork. When relationships are collaborative, TAs are likely to feel more valued and appreciated. This equally applies to the relationship between PAs and the person with disabilities as self-employed. to work in a collaborative manner.

Clearly, all of the above point to the need for a redefinition of tasks, roles and responsibilities, in addition to a strengthening of structures towards the enhancement of cooperation and collaboration. The RTM could be adopted to enhance positive working relationships which, in turn, can positively influence peer interaction and social integration. Team reflection on the benefits of having a TA and/or PA in specific situations necessitates the activation and strengthening of the voice of the person with disabilities. They themselves can be more involved in deciding what support they really need. Moreover, natural support is a potential solution, whereby peers or friends are more involved in supporting the person with a disability. Finally, further consultation with parents or relatives about the preferred support for the person with disabilities and how such support can be offered could cast light on the emerging roles of TAs and PAs.

Overall, raising awareness about the existence and roles played by PAs and TAs would be beneficial. TAs support students with SEN to attend mainstream schools and PAs offer people with disabilities to live an independent life. Learning to effectively work with an assistant while in school is essential for students with disabilities. This dynamic empowers the student, positioning them as the decision-maker, thereby fostering their independence and self-advocacy skills. Unlike teaching assistants who operate within the framework set by the teacher, personal assistants work directly under the student’s guidance. This distinction is vital in recognising the different support approaches: teaching assistants support educational goals collaboratively with teachers, while personal assistants follow the directives of the student, ensuring their personal needs and preferences are prioritised. Reflecting on these approaches is essential for creating inclusive environments that respect the autonomy and unique requirements of students with disabilities.

TAs and PAs play a significant role in implementing the rights of persons with disabilities to participate fully in society as decreed by the UNCRPD. Given the importance of this role, training and education varies considerably and is often ad-hoc and non-standardised across countries. Further discussion on baseline qualifications and skills could help to formalise the TA and PA roles? In addition, while employment conditions of TAs and PAs differ from country to country, precarious employment is more common among PAs, who are often employed privately by an agency or directly by a person with a disability. Thus, the terms and conditions associated with this role require greater development and refinement?

Considering the issues highlighted in this chapter, there is a need for a radical shift of the roles for TAs and PAs in the disability sector. Societal perspectives require a shift from the neo-liberal perspective towards an emancipatory approach. Persons with disabilities themselves should decide on what support they need and how best this is organised. While current legislation espouses the right for a person with disabilities to live a fully independent life, barriers exist which prevent the manifestation of this vision. One such barrier is attitudes and perceptions towards people with disabilities who often experience social exclusion and are regularly victims of discrimination. The unequivocal endorsement of empowerment, self-determination and participation as rights is paramount. For this to be realised, heightened awareness in society is the first step, followed swiftly by newly imagined models of co-operative living and working.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Reflect on the balance between providing necessary support and promoting independence. How can TAs and PAs ensure they are not hindering the social integration of those they assist? How can you, as a teacher, make sure they are as inclusive as possible?

- Discuss the potential conflicts that might arise between TAs and teachers or PAs and their employers. How can these relationships be managed effectively?

- Consider the qualifications and training for TAs and PAs in your country. What improvements could be made to better prepare them for their roles?

- How can the perspectives of the individuals receiving support be more effectively integrated into the planning and provision of assistance (especially in schools)?