Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

Teamwork in the Classroom

Outi Kyrö-Ämmälä; Becky Ward; and Silver Cappello

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“A few years ago, I was involved in an Erasmus+ funded project called THRIECE: Teaching for Holistic, Relational and Inclusive Early Childhood Education. Some of the work we did in the Irish part of the project was looking at relationships in the classroom. What was very special about this piece of work was it involved the whole school community. So, everybody was involved: teachers, special needs assistants, the librarian, the secretary, the caretaker; everybody in the whole school community came together, both in terms of teamwork and collaboration in the classroom. What was interesting was that through this project, the barriers across staff roles started to break down. So, for example, previously, if a teacher had a professional question that they weren’t sure about, they might ask a colleague, another teacher. However, when we were evaluating this project and having conversations with the people involved, they said one of the biggest benefits of this kind of relational approach across the whole school was that they started to recognise the expertise in other groups of staff. It might not have occurred to a teacher before to ask a special needs assistant for their opinion, and yet there was a huge bank of expertise there, and they were missing out on this expertise by not engaging with special needs assistants. Once those barriers began to break down, it meant that different groups of staff could really collaborate. Or let’s say the secretary might have been the first person to see the child on the way in the door and see an angry face on a child and think, “OK, I need to let the teacher know to be gentle here.” It made a big, big difference to the staff team as a whole to be able to rely on each other and draw on the expertise that was there.”

Dr. Leah O’Toole, Maynooth University, Ireland

Initial questions

Consider your experience in the classroom:

- Think of one good example of teamwork that you have observed or participated in. What characteristics made it successful?

- Think of a situation you have been in when the team did not work well together. What stopped the team functioning effectively?

- What kind of teamwork have you experienced in school or another pedagogical context? Who was working together? What did it look like?

Introduction to Topic

In inclusive classrooms, it should be possible for all students to learn in their own local neighbourhood (Slee, 2014), with education that enables them to reach their full learning potential (Booth & Ainscow, 2011), and feeling a sense of belonging to their school community (Qvortrup and Qvortrup, 2018). However, this is not without its challenges, and a teacher can face many difficulties, such as lack of time, material, learning spaces and personnel (Lingard & Mills, 2007). A teacher may also find it challenging to consider students’ individual needs (Joseph et al., 2013) and students may be left without appropriate support (Lumby & Coleman, 2016).

In this chapter, we focus on teamwork in the classroom. It is one solution to the challenges that a teacher may confront in everyday school life when working with diverse students. The core of our chapter is to describe what kinds of professional competencies teachers need when they are working in teams.

Teamwork and collaboration are at the heart of inclusive education; collaboration among adults, professionals and parents/carers and, above all, collaboration with and appreciation of the pupils. Inclusive education is values-led. The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2012:11) identifies the values which form the foundation for all teachers in inclusive education.

“These four core values are:

- Valuing learner diversity – learner difference is considered as a resource and an asset to education.

- Supporting all learners – teachers have high expectations for all learners’ achievements.

- Working with others – collaboration and teamwork are essential approaches for all teachers.

- Continuing personal professional development – teaching is a learning activity and teachers take responsibility for their own lifelong learning.”

In this chapter we focus on value 3 Working with others and how collaboration and teamwork are vital for teachers. However, teamwork also overlaps with the other core values, especially valuing learner diversity and developing personal skills in continuing personal professional development.

In order to value learner diversity and support all learners, multiple methods and perspectives are needed (Diana Jr., 2014). In this way, the benefits of teamwork become apparent. It is also important to recognise that teachers are lifelong learners and continuing personal professional development is important to improve our attitude and ability to work in teams and to learn skills for effective teamwork (Lindsay, Proulx, Scott, and Thomson, 2014).

The definition of teamwork in the classroom

Just putting people together does not make them a team. It has been stated that teams need “clarity of purpose, accountability, team structure, and trust” (Sparks, 2013: 29). Teamwork happens when a group of people work together to reach a common goal. Although each person brings their individual contribution, they influence the others in the team and in the same way, are influenced by their co-workers. At each step of the project, the team works to make a joint decision, and then moves on to the next step. When there are disagreements and different ideas, the team must work together to find a common solution. Finally, the common goal is reached with each person having contributed to the outcome (Radiæ-Šestic et al., 2013).

In a classroom, teamwork is describing, for example, how educational professionals can work together to prepare and deliver teaching, evaluate the learning, and plan future projects. Well-functioning teaching teams are essential to continuous improvement of teaching and learning, providing mentoring and support for new staff, benefiting students, teacher-teacher peer mentoring, and problem-solving with different perspectives (Sparks, 2013). Through collaboration, a system of flexible support can be built for the social communities of children (Lakkala & Kyrö-Ämmälä, 2017).

There are many different people who influence what happens in the classroom. There may be different kinds of teachers in the school, support staff, student teachers, therapists, the principal and senior leadership team, social workers, educational psychologists, the pupils themselves, and the families of the pupils. In this chapter we use the terms ‘student’ and ‘pupil’ interchangeably to describe the learners in the school. This reflects the language used in different school systems. We use the term ‘student teacher’ to describe those training to be teachers. Focusing on the classroom, on a day-to-day basis, teachers, student teachers, support staff, pupils and therapists are the people most likely to be in the classroom during the school day. Teamwork can be challenging because it relies on trust within these → relationships, valuing different people’s contributions, and finding ways to overcome differences of opinion (Whatley, 2009).

Key aspects

Dimension 1: Competence of the Teacher

In this section, the focus is on teachers’ competencies based on a document published by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2012). A combination of professional knowledge, both in terms of content and pedagogy, along with values and motivation aligned to learning, and self-regulation comprise the model of professional teacher competence (Baumert & Kunter, 2013). When characterising teacher competencies, it is crucial to distinguish between two elements: firstly, the concrete and visible actions seen when teachers engage in professional responsibilities, such as teaching; and secondly, the knowledge, skills and processes of perception, interpretation and decision making (including cognitive and non-cognitive competencies) that are critical for implementation but may not be observed by outsiders (richardWeinert, 2001). According to Koster and Dengerink (2008), the competence of a teacher includes a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and personal characteristics that allow the teacher to act professionally and effectively in specific teaching and learning situations.

In the Profile of Inclusive Teachers (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2012) teachers’ competencies are made up of three elements: teachers’ attitude, knowledge, and skills. A certain attitude or belief demands certain knowledge or level of understanding, it also demands skills in order to implement this knowledge in a practical situation. All the elements should be seen as the foundation for specialist professional development routes and the starting point for discussions at all levels on the context specific areas of competence needed by teachers working in different country situations. As identified earlier, the core value of ‘working with others’ highlights collaboration and teamwork as essential approaches for all teachers.

Teamwork in the classroom is also related to two other spheres: → teachers’ working with parents and families; and teachers’ working with other educational professionals. In this chapter, we focus on teachers’ collaboration with a range of educational professionals.

Teachers’ attitudes

Teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and values are connected to their practical decisions and strategies in the classroom (Buehl & Alexander, 2009). These background factors may come from previous experiences of schooling, or they may be concepts that are commonly agreed in the school community (Richardson, 1996). They are subjective, something a person holds to be true, and so may be resistant to change even in the face of conflicting evidence (Buehl & Alexander, 2009).

Attitudes, beliefs, and values behind teamwork in the classroom include some essential ideas, which are introduced in the Profile of Inclusive Teacher (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2012). Firstly, it is obvious that inclusive education requires all teachers to work in teams. Diverse classes present different challenges for teachers, as they try to be sure everyone is being challenged and learning the material. To do this alone, can be a huge task for one teacher and there are great benefits to teachers working with colleagues in a team. Traditionally, the teaching profession has been seen as an individual profession (Canaran & Mirici, 2020), but now it should be seen more as a team profession. Student teachers should also adopt this way of thinking during their studies. Collaboration, partnerships, and teamwork are essential approaches for all teachers and should be welcomed in all schools and classrooms. Moreover, collaborative teamwork supports professional learning with and from other professionals. In this way, the classroom is a learning organisation where each member learns from everyone and teaches everyone (Kools & Stoll, 2016).

Sometimes tensions arise in teamwork, for example, between teachers and support staff because there is insufficient time to co-plan and reflect (Dixon, 2003). Also, confusion on training and the unclear role of support staff may complicate teaching practices. Sometimes, for example, teaching assistants may not be included in staff meetings, and their work may be ignored in briefings and policy documents (Wilson & Bedford, 2008). The culture of inclusion and teamwork in the school needs to be broad, including all staff, and led by the senior leaders in the school (Wilson & Bedford, 2008). Teamwork needs effective communication, with the benefits resulting in a consistent approach for children in the school (Ward et al., 2021). Teachers act as reflective practitioners (Jay & Johnson, 2002). They analyse their work and develop their practice by assessing and then acting on their own learning.

Teachers’ knowledge and understanding

According to the Profile of Inclusive Teachers (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2012), teamwork in the classroom requires some essential knowledge and understanding including an idea of the value and benefits of collaborative work with other teachers and educational professionals.

Teacher education should develop student teachers’ theoretical understanding and provide opportunities for real life experiences about multi-professional work. There is a need to become acquainted with support systems and structures available for further help, input and advice and multi-agency working models where teachers cooperate with other experts and staff from a range of different disciplines. Also, understanding collaborative teaching approaches is important, where a team approach involves teachers, learners themselves, parents, peers, other school teachers, support staff, and finally, multi-disciplinary team members, for example therapists and teachers should also be addressed in teacher education. A common understanding of the language/terminology and basic working concepts and perspectives of other professionals involved in education are crucial for teachers: they need to have a common language when talking to each other about student issues. Additionally, the power relations between different stakeholders should be recognised and dealt with effectively in teacher education. In some situations, non-teaching staff, for example, support teachers and teaching assistants, are not given a voice and have less opportunities to contribute their knowledge to the classroom; but they may have a lot of experience and a different and valuable perspective in contrast to teachers (Mackenzie, 2011; O’Brien & Garner, 2001). Different types of knowledge exist and are useful for improving learning (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Explicit knowledge stems from training courses, reading, and qualifications, whereas tacit knowledge comes from experience, school systems, and the environment or culture. A joined-up team approach draws on each person’s knowledge, sharing power, creating space, and opportunity for voices that often go unheard (Nind, 2014; Parsons, 2021).

Teachers’ skills and abilities

Teamwork relies on teachers developing social skills, including relational skills, emotional competency, diversity competency, intercultural competency and interaction (Metsäpelto et al., 2021). Furthermore, generic competencies (for example information-processing abilities), and affective and motivational competences (for example abilities to regulate emotions) are fundamental teacher’s skills (Blömeke & Kaiser, 2017).

In the Profile of Inclusive Teachers (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2012), essential skills and abilities related to teamwork in the classroom to be developed during initial teacher education are introduced. The initial teacher education should include implementing classroom leadership and management skills that facilitate effective multiagency and team working. Student teachers need to be equipped for co-teaching and working in flexible teaching teams. For teachers it is also necessary to learn how to work as part of a school community and draw on the support of internal and external resources. In the classroom they need preparation on how to build a class community that is part of a wider school community. When thinking about the development processes of schools, student teachers should have skills to contribute to whole school evaluations, review and development processes and collaborative problem solving with other professionals. Schools do not act alone, and therefore teachers are contributing to wider school partnerships with other schools, community organisations and other educational organisations. Moreover, they need to be drawing on a range of verbal and non-verbal communication skills to facilitate working cooperatively with other professionals.

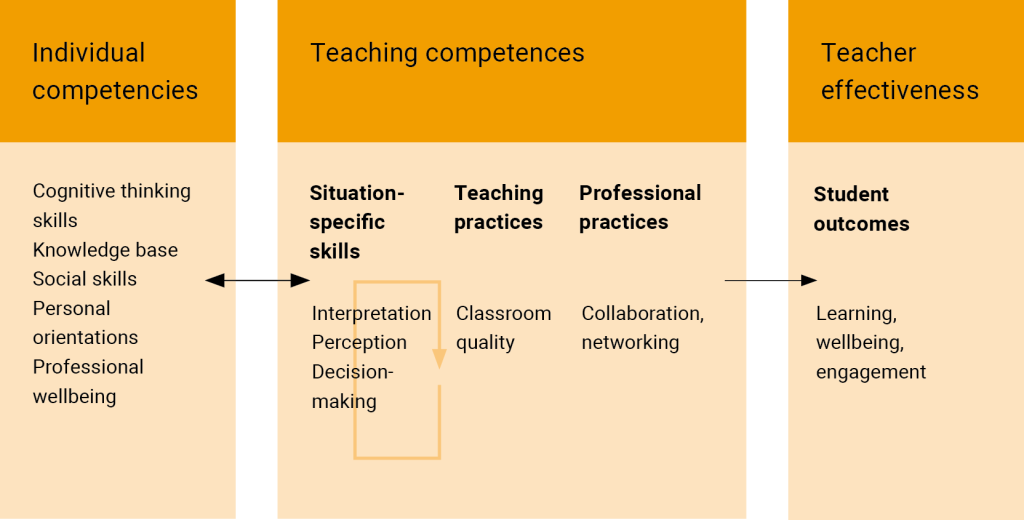

In teacher education around the world, efforts have been made to define the key skills of the teaching profession for many years. Teaching is a multidimensional and challenging profession that demands expertise which is developed and renewed throughout initial teacher education and the professional’s career. According to Desimone (2009), a teacher’s development is a continuous process and includes changes in the teacher’s cognitive and affective skills, used in teaching tasks and in adapting classroom practices. Ideally, the core of teacher education includes skills that make a difference in the classroom and promote student achievement (Hattie, 2009). The Multidimensional Adapted Process model of teaching (MAP) (Figure 1) describes the key competence domains perceived to be critical for the teaching profession and depicts them as a comprehensive teacher competence model (Metsäpelto et al., 2021).

Figure 1: The Multidimensional Adapted Process model of teaching (MAP)

The MAP model is based on Blömeke and colleagues’ (2015) model, which divides (1) the competence related to the efficient performance of the teacher’s work, (2) the individual knowledge and skills underlying and enabling effective teaching, and (3) the situational skills to perceive, interpret and make decisions in teaching and learning situations. The MAP model outlines a teacher’s successful work performance (competence) and the critical knowledge and skills that enable and promote it (competencies) and thus aims towards a more comprehensive understanding of the key skills of teachers’ work and their development at different career stages. In the MAP model, there are five core competencies of teachers: cognitive thinking skills, knowledge base of teaching and learning, social skills, personal orientations, and professional wellbeing (Metsäpelto et al., 2021). In the model, the ultimate goal of teacher activity is teacher effectiveness at the students’ level, in students’ learning, motivation and well-being. As Berliner (2001; see also Klassen & Kim, 2018) has stated, some attributes thought to be included in teacher competence, are specific to the educational environment and to the cultural, social, and task-specific context, while some other attributes are universal.

Dimension 2: The Meaning of Context

Teamwork is shaped by the context in which teachers work.

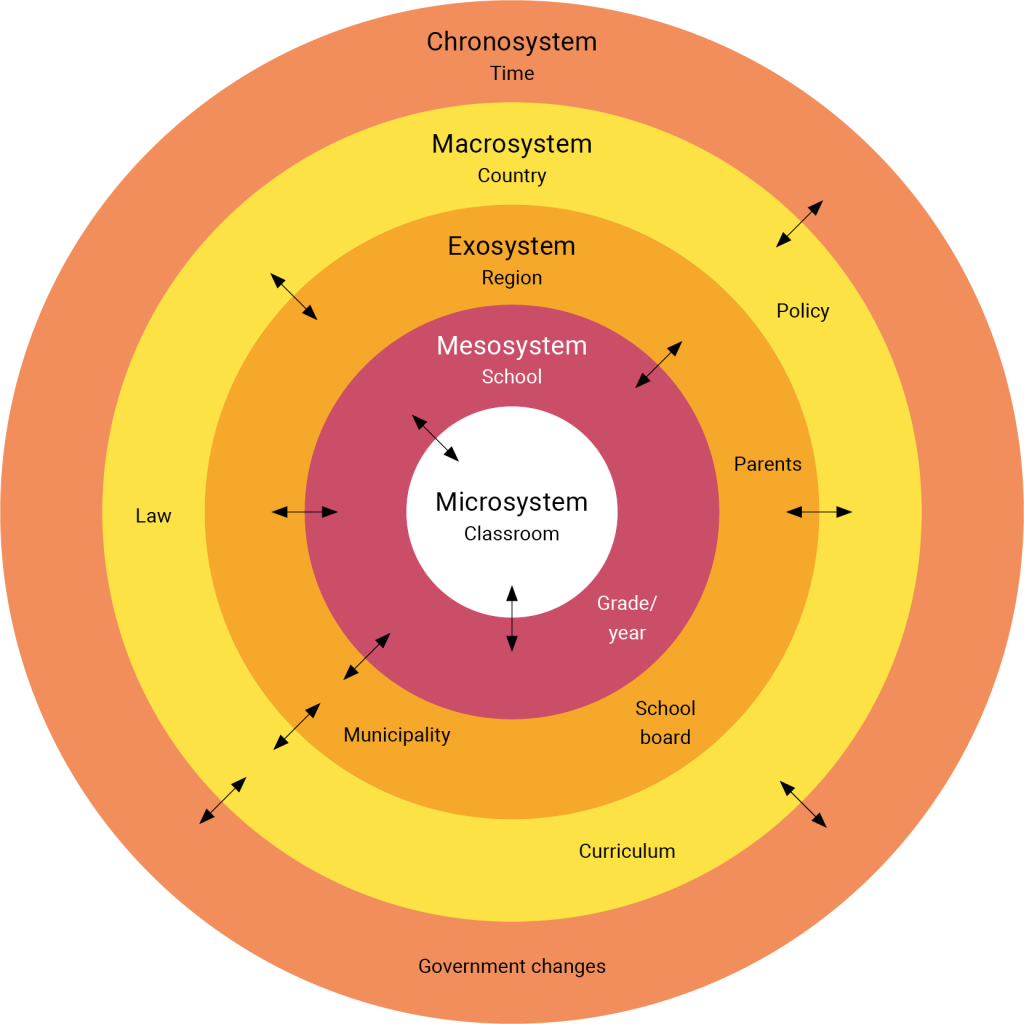

Like bioecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), the classroom teacher is situated in a classroom. This classroom is situated in a school and the school is situated in a regional and national context. At every level, the context influences what happens in the classroom. The chronosystem describes those changes that happen over time. Additionally, the bidirectional interaction between different levels, i.e. the relationship between classroom and whole school or whole school and region, also influences the way in which teachers work in their own classrooms.

Figure 2: Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Systems Theory in the Educational Context

The classroom can be thought of as the microsystem. The teacher plans, delivers and evaluates each lesson. They can potentially work as a team with other teachers, student teachers, teaching assistants or external therapists who come into the classroom.

The classroom is situated in the school, the mesosystem. Within the wider school, there may be requirements to ensure each teacher communicates with other teachers in the same year group or education phase.

The regional or local school board can be considered the exosystem. Schools may be grouped together in local areas, or regional school boards/municipalities may provide guidance or regulations for local schools. This could also include parents and families, and external professionals working with the school.

The regional school board or municipality sits within the national system of education, which can be thought of as the macrosystem. The macrosystem includes national education policies, including the curriculum and staffing structures which will influence how teamwork can happen in your school. There may be a shortage of types of school staff; for example, specialist subject teachers, special education teachers, support staff, or healthcare professionals who work in the classroom.

This macrosystem is situated in the chronosystem as changes in policies and procedures happen over time; for example, when a new government is elected.

Some national education policies are very broad, and others narrow. For example, a broad national curriculum provides an overview of each subject area and flexibility and autonomy for individual schools or teachers to plan, deliver and assess their schemes of work and lessons. However, in other countries, the national curriculum is prescriptive with specific textbooks identified for areas of the curriculum and standardised assessments for all pupils. Similarly, staffing structures vary from country to country. For example, in one country a classroom could have one teacher and three assistants for 30 children. Whereas in other countries, a classroom may only have one teacher for 30 children.

At each contextual level, there are several factors to address. Table 1 provides some practical examples from different school systems and contexts considering the members of the team and the way in which this level might influence teamwork in the classroom.

Table 1:

| Bioecological system | Education level | Authority/ responsibility | Considerations | Practical examples from different school systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsystem | Classroom | Lesson plans, delivery of lessons, evaluation and assessment | Potential/actual members of the team in the classroom | A teacher and a special education teaching assistant (TA) work in the same classroom. The teacher asks the TA how to differentiate the learning for a group of children with special educational needs. They then plan the lesson together as a team. |

| Mesosystem | School | Schemes of work, phases of education | Other classrooms in the year group or education stage | In a school, there are three classes in grade 5. Each class has one teacher and no additional staff. The class teachers want to work as a team but are not able to do this in each classroom. So, they meet outside the classrooms and plan a series of lessons on a topic. Each teacher then delivers the lessons independently in their own classroom. After the series of lessons is finished, the teachers meet again to evaluate the scheme of work. |

| Exosystem | School board/regional education body | Regional variations on national policy | Partnerships between schools within a region | Although the national education policy allows solo teaching or co-teaching, a regional school board wants to promote co-teaching and introduces a policy that all schools in their area must incorporate co-teaching in the school. Each school then organises the classrooms to enable co-teaching to happen. |

| Macrosystem | National education policy | Curriculum, standardised assessments, staffing policies, initial teacher training requirements | Required qualifications/professional standards for education professionals or external professionals e.g. therapists | The national policy for children with special educational needs requires a child with an IEP to receive individual support within the classroom. The class teacher has 5 children with IEPs within the classroom who are supported by two classroom assistants. There are now three staff members in the classroom who can work as a team. |

| Chronosystem | Changes over time | New governments, education minister | Introduction and management of new policies and curricula | A new government is elected and changes the education policy which increases or decreases the number of staff in each school and each classroom. |

There are many ways in which teamwork can operate in the classroom, depending on the context and the members of the team. Three examples follow, exploring co-teaching, pupils’ voice, and collaborations.

Co-teaching methods and forms of collaboration

One important example about teamwork in the classroom in a practical way could be co-teaching, which is a practice where two or more teachers (class and/or support teachers) plan, teach and assess together for a group of students. According to Friend and Cook (2007), there are six types of co-teaching methods for working in teams, where big triangles are teachers and small triangles are students (Figures 3-8 created by authors), but it is important to use the approach that most effectively meets the needs of the students in a specific context:

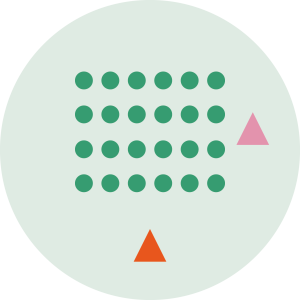

Figure 3: One teaches, one observes.

One teaches, one observes: one teacher conducts the lesson, while the other simply observes students’ learning processes and collects different kinds of data which have been determined in advance.

Figure 4: One teaches, one assists.

One teaches, one assists: one teacher teaches a full group lesson, while the other teacher roams and helps individual students, often providing additional support for learning or behaviour management.

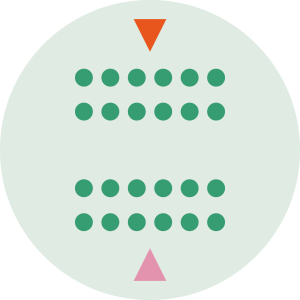

Figure 5: Parallel teaching

Parallel teaching: the team splits the class into two groups and each teacher teaches the same information at the same time to a smaller group.

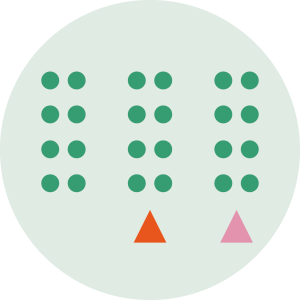

Figure 6: Alternative teaching

Alternative teaching: one teacher instructs most of the class and the other teacher teaches an alternate or modified version of the lesson to a smaller group of students.

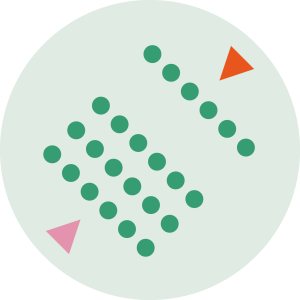

Figure 7: Station teaching

Station teaching: the class is divided into three or more groups, where students rotate through the stations, while the teachers teach the same material in different ways to each group; if there are more stations than teachers, at least one will focus on independent work or practice opportunities, while the others may be managed by students.

Figure 8: Team teaching

Team teaching: both teachers are in the room at the same time but take turns teaching the whole class, like co-presenters.

Co-planning for positive collaboration

Co-planning is one of the three co-teaching phases. It is really important because it represents the starting point of the process. Teachers have to plan collaboratively (co-plan) because co-teaching is not possible if one teacher handles the planning alone (Shumway et al., 2011). Initially it is not easy, because the collaboration could be influenced by the number of students in the class, pupils individualised or personalised needs, the additional work and time needed, teachers’ flexibility, their relationships and their interpersonal communication skills (Cramerotti & Cattoni, 2015).

There are some important aspects for co-planning to be considered. Firstly, the roles and responsibilities for teachers before, during and after each lesson need to be discussed. These would include who does what, when, where and with whom. Secondly, expectations about the lesson structure and the rules for the class need to be agreed to ensure consistency in the classroom. Thirdly, teaching skills, tools, and methods to apply in the classroom need to be agreed. Finally, important documents, such as reports, tables, and tools for working together, need to be prepared and completed. Teachers should co-plan with short, regular meetings, in order to have a common approach to the delivery of the teaching and learning process. The team need to agree on the goals, the learning process and individual needs of students, the teaching methods and lesson structures, the different activities for a variety of groups and single students, and the evaluation methods (Cramerotti & Cattoni, 2015).

Co-planning introduces diversity into the planning and delivery of teaching, as staff members share best knowledge and practice, and increases representation of people from different cultures, backgrounds, and perspectives. This reflects the wide range of students with different needs and backgrounds. A more inclusive classroom is developed as co-planning between teachers, and of course between teachers and other specialists, enables a multi-disciplinary view of pupils’ needs and helps to develop effective interventions. Each staff member brings a diversity of skills and resources ensuring that each student receives the support they need. In addition to this, collaboration between teachers can serve as an example to students of cooperation, empathy, and appreciation of diversity, fostering inclusive thinking.

Co-assessment for teamwork.

Co-assessment covers two different concepts. On the one hand, the teachers need to evaluate their lessons, actively discussing and sharing their ideas and practices (Conderman & Hedin, 2012). This might include self-evaluating the teaching and then revising some of the activities. On the other hand, teachers also need to assess the learning of pupils, including their engagement in the lesson and their completion of the learning outcomes.

Assessment might involve collecting multiple sources of information in which each teacher shares data providing different types of information about students’ progress (multidimensionality) (Ghedin, Aquario & Di Masi, 2013). It could also be done using a participative approach to assessment with students themselves (self-evaluation).

Deidda and Silvestro (2015) provide some sample questions for self-evaluation in teams:

- How were the time schedules for planning respected?

- How did pupils react to the proposed activities?

- What effective forms of communication were used?

- List any social skills needing to be reinforced or taught.

- Describe how co-teaching is effective.

- How were the goals achieved?

- Identify any problems that occurred during the lesson. How were they managed?

The inclusion of students’ and pupils’ voice

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNESCO, 1989) introduced Article 12 in 1989: the right for children and youth to take part in decision-making processes that affect them. As a consequence, starting from the 1990s, educational research has given a central role to students’ voice. One particular aspect that has been considered and discussed in educational research is strictly connected with the idea of having a voice and of expressing it as a right, since school and education highly affects children and youth. In this conceptualisation, the word ‘voice’ goes beyond the understanding of voice in terms of sound and information; it stands for presence, participation and the power of the individual being (Cook-Sather, 2006). The Student Voice approach in educational research simply means listening to students and taking into account their opinions in order to consider their point of view in research and in changes for education policies. In the field of inclusive education this issue is particularly relevant as it makes research methods more participative and inclusive. It is also very demanding because it requires data collection instruments that can give voice to all students, including disabled students, in a reliable way. Pupil voice has become increasingly important in educational research at an international level, but it can only be authentic if pupils feel free to express their opinions and point of view. The reliability of student voice is also connected with a participatory culture that creates a positive context for expression. Students should be encouraged to participate in debates and to explain their opinions (Fielding, 2004). There is also the issue that students may have something to say, and their contribution is useful for the whole teaching–learning process, but they do not know how to proceed and their opinions remains excluded (Rudduck & Fielding, 2006). For this reason, work has to be done within the school context so that it is seen as a supportive environment for participation, enhancing the quality of research based on students’ voices. The Lundy Model of Participation provides a framework for best practice guiding the participation of children and young people in decision-making (Lundy, 2007). The key principles include Space (providing a safe space in which children can speak up and share their views), Voice (facilitating the sharing of views by children), Audience (ensuring that children’s views are heard by decision-makers), and Influence (ensuring that children’s views are acted on where appropriate). The Lundy Model can be used by any educational setting to guide the development of pupils’ voices.

The Montessori approach is an important and concrete example of giving voice to students. This consists of inclusive teaching that respects the individual in their learning, with an environment organised in such a way that the individual pupil can direct their learning, based on their interests, preferred methods, and the time needed to complete the tasks. The Montessori approach provides pupils with the space to take an active role in their learning. For the first six years of age, the materials are mainly sensory, i.e. they allow children to gain appropriate knowledge by actively experiencing phenomena (touching, moving, interlocking, classifying, etc.), while for the following six years, an attempt is made to offer a school environment that responds to the curiosity of boys and girls, to their desire to understand the world, encouraging social participation and opportunities for individual and collective commitments aimed at empowerment (Caprara, 2022). The educational context makes it possible for the pupil to choose a task on which to concentrate and to choose the method of learning; either independently or by collaborating with small groups of classmates. The teacher then devotes their time to observing the class, facilitating the learning for each pupil, providing an educational context characterised by movement, freedom of choice, collaborative work, and self-determination of each pupils’ learning goals (Caprara, 2022).

Teachers’ collaboration with other educational professionals

One of the teacher’s most natural co-workers is the support teacher or teaching assistant. The teacher and the teaching assistant can plan, implement, and evaluate the teaching together and share the responsibilities of the teaching process. Of course, the main responsibility for teaching is always with the teacher, but the teaching assistant is an essential part of teaching a diverse group, as they can be responsible for certain pupils or groups (Groom, 2006). The teacher must recognise the assistant’s tacit knowledge: they often have a lot of experience with pupils and know their strengths and challenges very well and so are a real expert in teaching and learning situations (Greenway & Edwards, 2020). Additionally, when teachers and assistants work together in a team, they bring multiple views and attitudes, which might positively challenge those currently holding negative perspectives (Greenway & Edwards, 2020).

Teachers also emphasise the importance of multidisciplinary teams in the classroom (Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2011). To support children with particular special educational needs, classroom teams may also include therapists; for example, physiotherapists, speech therapists and occupational therapists (Lindsay et al., 2014). The benefits of these multidisciplinary teams are that both educational and health-related perspectives can inform the teaching and learning activities in the classroom. A range of strategies and advice can be considered from these different perspectives. Additionally, each professional has their own relationship with the child and can consider how best to support a child in a variety of activities (Lindsay et al., 2014). Therapists can participate in lessons, lead individual tasks, or contribute to joint training with the pupil they support. Equally, the therapist does not always have to work one-to-one with the pupil; seeing the pupil with their peers can broaden the therapist’s perspective in the learning process (Richardson, 2002).

The challenges of teamwork in the classroom

One of the challenges for teamwork is finding the time and space to meet, particularly if you have a busy teaching schedule, considering that teamwork will almost certainly involve an increase in additional work at the beginning (Hestenes et al., 2009). Finding space could also be problematic if classrooms are small in the school where co-teaching-methods could be implemented. Having a regular planning session, even an hour each week with your co-teacher, will help teachers to get started in co-teaching. Co-teaching may initially require more time than planning and teaching alone, but over time, as experience is gained and teachers get to know each other better, the need for planning is likely to decrease. No one can be forced to co-teach, and each teacher must be able to do their job in the way that suits them best. However, positive, and effective models of co-teaching can encourage even the most sceptical teacher to give it a try (Cramerotti & Cattoni, 2015).

There might also be challenges to do with your context; whether colleagues in your classroom, school or system want to work in teams, what attitudes your colleagues have towards each other, or what skills each person has. One particular issue might be teachers’ fear of losing autonomy and responsibility in the classroom (York et al., 2007). Additionally, teachers may feel under scrutiny by their peers and anxious about other teachers’ perceptions of their approach or competence (York et al., 2007). In order to overcome this challenge, initially, the important thing is to understand why a colleague may not want to co-teach. Rather than making assumptions, ask them what they think the positives and negatives are with co-teaching. If they can only see problems, prompt them to think of any benefits, or suggest some yourself, for example, diversity of approaches. You may even start by explaining that you want to develop your own teaching and so are keen to work with others. You may be able to use examples of how a colleague seems to have very positive lessons with a certain student that you find more difficult to teach, and vice versa.

Resolving differences could present obstacles if teams have very different ideas and practices to share. Conflicts between teachers might be difficult to resolve and if there is confusion about the roles of each team member, it may hinder decision-making (Canaran & Mirici, 2020). This is where it can be helpful to clearly identify each person’s role in the planning, delivery, and assessment of the learning. Additionally, it is good to identify practices that both teachers use and incorporate those to start with, before adding in more individual practices once trust has been established.

The benefits and importance of teamwork in the classroom

However, one of the benefits of teamwork is that it brings together different perspectives and different experiences taken from everyday practice. Teachers can then reflect on and evaluate their own practice (Boud & Hagar, 2012; Doppenberg et al., 2012) and build capacity, which tends to show longer-term results (Stoll et al., 2006; Vrieling et al., 2016; Wenger, 1998). There is evidence to show that teamwork for teachers can enable them to develop innovative teaching pedagogies, for example working in small groups, and improve teachers’ job satisfaction and self-efficacy (European Commission, 2013).

Another benefit is that pupils see and hear different types of teaching – different explanations, different activities – which can help their learning, meet their different learning styles, and enhance their social development (Murawski & Swanson, 2001; Sapon-Shevin, 2003). Over time, teamwork can also help teachers to share the workload, for example, creating resources and developing lesson plans, and reduce the time that each teacher spends on preparation.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- What attitudes, knowledge or skills do you need to develop for teamwork?

- Thinking about your context, what are the challenges for you in participating in teamwork in the classroom? How could you overcome the challenges?

- What do you see as the three greatest benefits for inclusive education from working in a team?