Section 1: Developing Inclusive Educators

The Role of Values in Inclusive Education

Lydia Murphy; Mahvand Sahranavard Espily; Petra Auer; and Tommaso Santilli

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Now I know that it is very important to me to make friends and to care for nature. Having friends is what counts in life. It is not important to me at all to be rich and powerful or to be like the others. If we are all equal, what kind of life would that be?” I stand about three metres in front of him trying to suppress the reflex to rub my eyes as well as the urgent need to ask the person next to me for a quick pinch. Instead, I just stand there, grinning from ear to ear and cannot believe it. The person next to me is an experienced middle-aged primary school teacher, also smiling broadly, perhaps not quite as exaggeratedly broadly as I do. Him – that is a nine-year-old fourth grader talking about what is important to him in life (cf. Auer, 2021, p. 1). And when we talk or think about what is important to us in life, we talk and think about values (cf. Schwartz, 2012).

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What are values?

- Why do values play a role in inclusion/inclusive education?

- Where do I find values in the school context?

- How can I work with values to foster inclusion?

Introduction to Topic

As the example case above illustrates, values reflect what matters to us, what we find important, and can also help answer the question of who we are. In this case, the fourth grader seems to place high value on friendship, caring for nature, and appreciating diversity. Based on this information, and drawing from a broad definition, (Ainscow, 1991; 1997; Ainscow et al., 2013; UNESCO, 1990, 1994) we could argue that inclusion is his cup of tea[1]. When it comes to inclusion and, more precisely, inclusive education, scholars have written more specifically about the concept of inclusive values (e.g., Ainscow et al., 2006; EADSNE, 2012; Booth & Ainscow, 2016; Väyrynen & Paksuniemi, 2018; Ianes et al., 2024). These scholars contend that values provide the foundation for developing inclusive education systems, and for successfully implementing inclusion from theory to practice. However, it is evident that, despite discussing values, these scholars often refer to different interpretations of the term. Therefore, in this chapter, we will explore in more detail why and how values play (and should play) a role in inclusive education, where they appear, and how we can work with them on a practical level. We will initially define what values are and propose a theoretical model, currently the most frequently cited across different research disciplines, but having its origin in social psychology. So, make yourself a cup of tea (or coffee) and let us venture into this topic …

Key aspects

What are values?

Values, as a central concept of social science, play an important role in many different disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, anthropology) (Schwartz, 2006). However, since different academic fields have employed the concept of values, numerous understandings of the construct have co-existed over the last few decades. An agreement on what these values are, what constitutes them, what they contain and how they are structured, has been absent for some time (Schwartz, 2012). What do we mean when we talk about values? What do we refer to?

The Basic Human Values Theory

In 1992, the sociopsychologist and cross-cultural researcher Shalom H. Schwartz published an article introducing a theory of basic human values by identifying the common features from previous definitions and approaches (Davidov et al., 2008). In addition to other scholars, his theory was predominately based on the work of Milton Rokeach, whose work has mostly been shaped by the understanding of values in empirical science (Frey, 2016). Within his theory Schwartz (1992, 1994) defines values as “[…] trans-situational criteria or goals […], ordered by importance as guiding principles in life” (Schwartz, 1999, p. 25). To put it more simply, values give an answer to the questions “What is important to me? What goals do I strive for? What are the guiding principles of my life?” (Döring & Cieciuch, 2018, p. 17). As such, values are therefore part of the self-concept (Hitlin, 2003; Vecchione et al., 2016), in response to? who I am (Döring & Cieciuch, 2018).

Part of Schwartz’s work consisted of the categorisation of values. But what did he do exactly? He collected countless words that people around the world, and in different languages, that were used to refer to values (i.e., specific values) and summarised them into 10 types of values based on their underlying motivational goals (see Table 1). These 10 value types are common to every human being all over the world, in other words, they are universal. Nevertheless, persons or groups of persons (i.e., cultures, societal groups, school classes) can prioritise them differently, which leads to contrasting value priorities or hierarchies (Schwartz, 2012). Hence, individuals share the same set of values within? a universal structure, but individuals or groups differ according to which values are more important to them and which ones are not.

Table 1: Value types, their underlying motivational goal and examples of specific values

| Value type | Motivational goal | Specific value |

|---|---|---|

| Power (PO) | Social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and resources | Social power, authority, wealth |

| Achievement (AC) | Personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards | Successful, capable, ambitious |

| Hedonism (HE) | Pleasure and sensuous gratification for oneself | Pleasure, enjoying life |

| Stimulation (ST) | Excitement, novelty, and challenge in life | Daring, varied life, exciting life |

| Self-direction (SD) | Independent thought and action—choosing, creating, exploring | Creativity, curious, freedom |

| Universalism (UN) | Understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature | Broad-minded, social justice, equality, protecting the environment |

| Benevolence (BE) | Preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact | Helpful, honest, forgiving |

| Tradition (TR) | Respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide for the self | Humble, devout, accepting my portion in life |

| Conformity (CO) | Restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms | Politeness, obedient, honoring parents and elders |

| Security (SE) | Safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and, of the self | National security, social order, clean |

Adapted from Schwartz, 1994, p. 22

Brief digression

The Circular Structure of Values

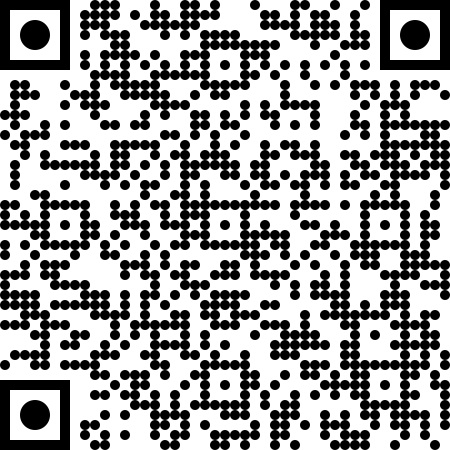

The ten value types are related to one another in that they can harmonise or conflict with each other (Davidov et al., 2008). That is, the value of benevolence, for example, conflicts with the achievement of power values like social power, however, it is incompatible with universalism values like social justice. The dynamic relationships between all of the value types are portrayed graphically in the circular structure of Schwartz’s value system (Schmidt et al., 2007) as shown in Figure 1. Values lying next to each other are in harmony, e.g., actions motivated by them are compatible with each other, whereas those on the opposite side are in conflict, e.g., actions based on these values are rarely combined.

Figure 1: Theoretical circular model of dynamic relations among the 10 value types

Example

This situation is one of the rare occasions when the impact of values on decision taking becomes conscious: in other words, there is a need to decide between two cherished, but equally, conflicting, values (Schwartz, 2012). For many, values unconsciously direct our everyday decisions and actions. The example above also reveals the importance of conflicting values. For instance, I can value benevolence, and at the same time, I can cherish achievement, i.e., being successful and ambitious. Furthermore, within a group, people may prioritise differing values, as the case above represents. Nevertheless, having different value priorities that guide us can be fruitful, and must not be a cause for conflict. A group can be more successful when there are explorers (self-direction), those who help others (benevolence) and also leaders (power) and those who take care of nature (universalism; cf. Döring & Noam-Knafo, 2019). As Schwartz (2012) argues, the pursuit of certain values can have negative consequences, such as when power values may be important for some, or when social relationships are harmed or someone is taken advantage of. On the other hand, inherent in power values is the motivation to work for the interest of a group. Consequently, values alone cannot be defined as “good” or “bad”, but their meaning and value is crucial for the functioning of societies (cf. Döring & Noam-Knafo, 2019).

Adding complexity:

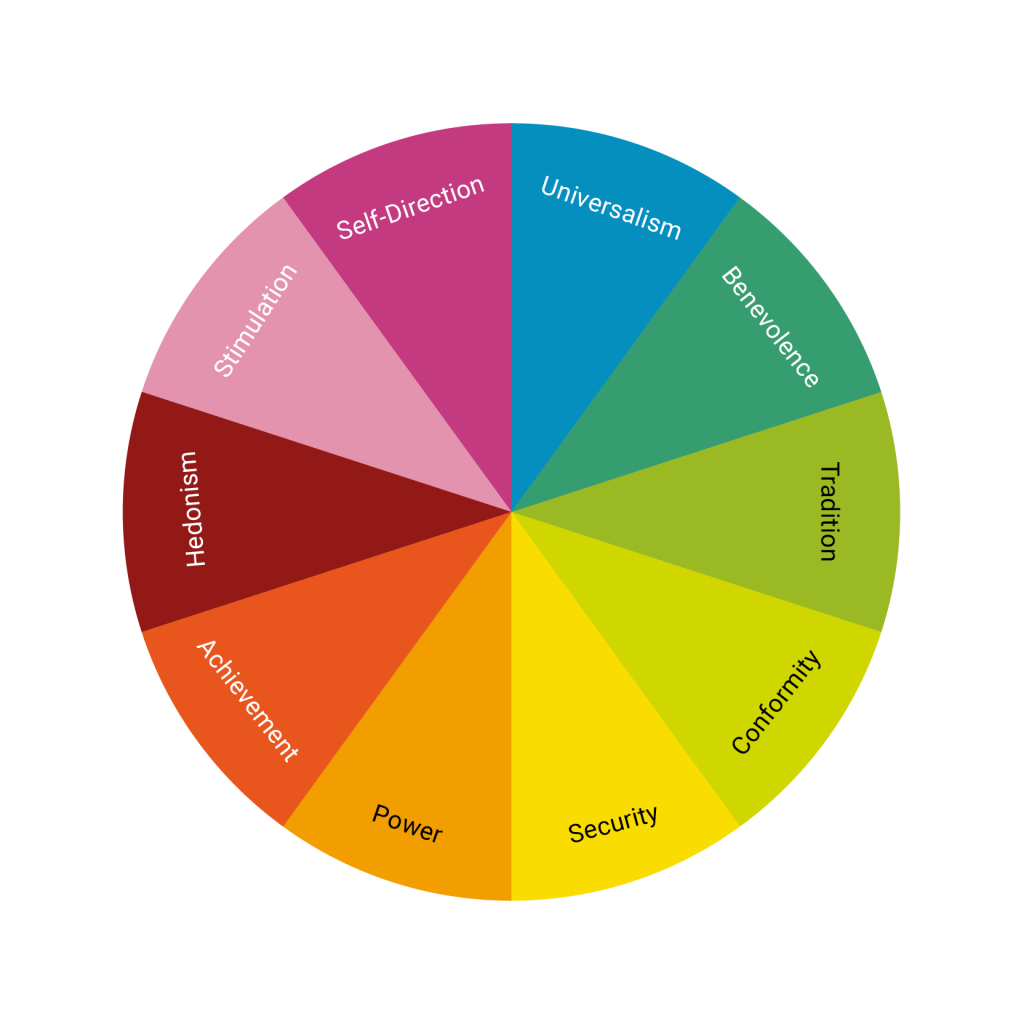

Figure 1 shows a simplified version of the circular model. According to Schwartz (2012), values form a continuum of related motivations which gives rise to a circular structure. The ten value types (according to their competing nature) can be combined to four higher order values by organising them into two bipolar dimensions (see Figure 2). The value type hedonism cannot be related explicitly to one higher order value, but is attributed to two of them. The value types can further be classified based on the interest of attaining values (i.e., some value types focus on personal interests while others focus on social interests) or are dependent on the role of anxiety (i.e., some values are based on anxiety and others are free of anxiety) opening up a further two bipolar dimensions. All of these possible classifications are dynamic principles leading to the dynamic structure of value relations.

Figure 2: Dynamic principles of the structure of values

In summary, values play an important role in our lives and motivate our actions. Depending on their underlying motivation, values can be summarised into value types which interrelate dynamically with each other either through harmony or conflict. In light of this value theory, the importance of values in everyday life seems almost logical. But how can this be used in inclusive education …

Why are values important when it comes to inclusion?

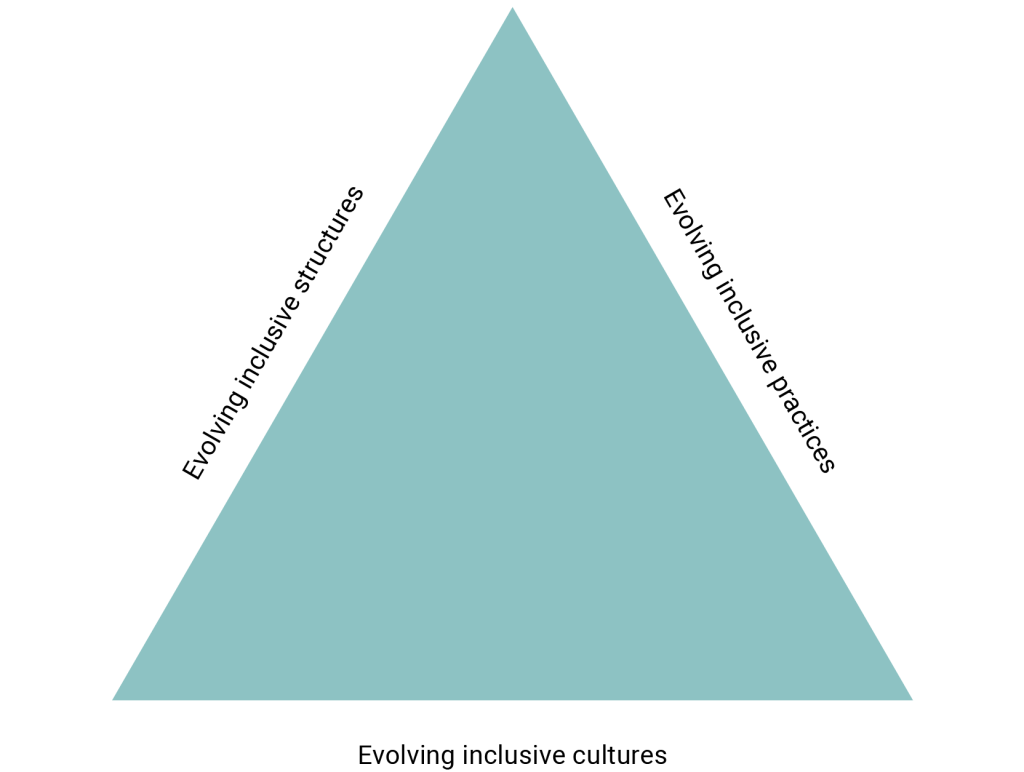

Figure 3: Three dimensions of inclusive school development

Even though all three dimensions highlighted in Figure 3 are essential for an institution or society to become inclusive, if there is a lack of shared values it might be that changes in the other two dimensions risk a mere formal action (Demo, 2013) . It is only through the activities of individuals that effective change can be sustained? Indeed, Booth and Ainscow (2016) also propose a set of inclusive values that schools can work with in a variety of ways (i.e., the Index for Inclusion is an instrument that can be used to work on the community level, the school level, the class level, or on the individual level). On the other hand, they also present a set of exclusive values, which might hinder schools in developing towards inclusion.

Brief digression

Example

Where do I find values for Inclusive Education?

Considering how values can be defined in terms of content and features, it is important to understand the dimensions in which values lie (i.e., where) in order to work with them, and orient them, towards the promotion of inclusion across educational contexts. In this sense, values operate within multiple levels of human life particularly as they are maintained, negotiated or transformed across contexts and social groups. When it comes to education, learning environments constitute one of the most impactful dimensions in which values can be transmitted (Ristevska et al., 2019), as schooling encompasses socialisation and personal development.

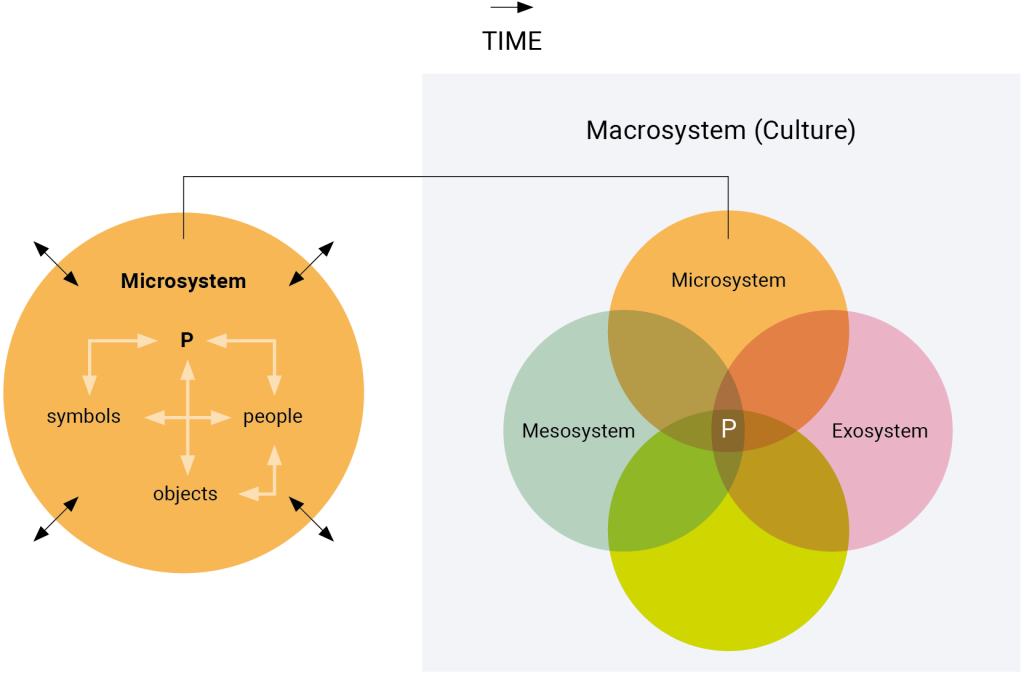

The ‘Where’ section moves through deeply reflective and nuanced practical applications of case studies from both a national and international perspective. Other chapters have highlighted Bronfenbrenner’s first edition of the Ecological Model (1979, see chapter → Neuroinclusion: A school community approach ). However, this chapter on inclusive educational contexts is discussed using an adaption of the Ecological Model, which describes movement within the Microsystem as linkage through the Mesosystem (Hayes et al., 2023; Sheldon, 2019). This movement brings with it possible conforming and conflicting values. Young children and adults are viewed as active participants with individual values, wants, needs and desires in their world (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). This occurs in an inclusive bi-directional way within families (Microsystem) and within communities (Exo- and Macro- Systems). Finally, this section points to the difficulties and successful application of individuals living close to their values in education and society.

The Process-Person-Context-Time Model

The next sections will frame the importance of values in education using Bronfenbrenner’s and Morris’ (2005) most up to date model Process, Person, Context over Time (PPCT) which highlights the potency of values in inclusive communities. Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) provided a detailed description of bi-directional actions using the PPCT model, which they defined as proximal processes. This model illustrates the relational engagement with others (including inanimate objects and symbols) in context over time. Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) called these engagements the engines of development. A person’s engagement with their environment becomes more complex, causing the development to progress in a particular direction. Merçon‐Vargas et al. (2020) considered Bronfenbrenner’s perspective on the engines of development as slightly narrow as it only theorised child development from a positive perspective. Instead, they suggested that inverse proximal processes also produced dysfunction (either positive or negative), which are constantly evolving over time.

Figure 4: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT model

The active Person (P) is engaging in Proximal Processes with people, symbols and objects within a microsystem, interacting with other contexts, and involving both continuity and change over time (Tudge, 2008, p. 69). Bronfenbrenner maintained that the person is the active participant in their worlds; and includes a person’s values and beliefs (Hayes et al., 2023). Relocating human development internally in relations and externally with the environment. Values and beliefs lay the foundation on which education is occurring. Bronfenbrenner’s thoughts progressed from the previous dichotomous focus on the body separate from the mind or what had become nature versus nurture debate of attachment, to a more harmonious inclusive perspective of child development. Subsequently, Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2005) stressed the importance of reciprocal relationships within the social context on the development of the body? rather than just the brain (Bronfenbrenner, 2005; Osher et al., 2018). Nestled in these inclusive relational processes are the significance of both conscious and unconscious values, beliefs, traditions and cultures. Bronfenbrenner relied on the work of Kurt Lewin to position his thoughts on values. He viewed values as fundamental in the processes of human behaviour (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Cartright, 1951). Lewin (1951) highlighted that the values among groups were likely to drive group engagements in both positive and possibly negative ways. Crucially, values, tradition and norms are culturally and contextually loaded.

Processes of Values

To begin applying the PPCT model, we will start by focusing on the first P for processes of inclusive relationships in education. A process is at the core of human engagement. Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2005) called these Proximal Processes, relations that are dynamic, active and consistent engagements with the environment. Previously, values were not prioritised as positive or negative but rather as beliefs driving behaviour. However, Wilkowski (2022) suggests that vices also need a voice within this framework. Vices can be understood as the counterpart of virtues, which, as stated earlier (see brief digression above), are guided by underlying values, as are vices. The vignette below highlights how an educator strives to uphold her values while addressing the contrasting values of the educational system.

Example – The Processes of Values in Educational Inequity

Chris was a teacher in a German school. She was fascinated by how every classroom she walked into would have a list of the classroom rules supported by their teacher training. These sets of rules included her own classroom. The children all have rules to follow, still, she wondered about the inability of the rules to be followed. Chris taught her students to always question everything they were told, no matter how powerful or experienced the person they seemed with the information. Nonetheless, Chris began to reflect on this nested paradox from her teacher training instilling conformity whilst also trying to instil the children’s wonder and curiosity. Upon reflection Chris thought ‘how are these rules developing my children into flourishing human beings?’ Chris brought her reflections to her class and after a discussion she realised the disparity between rules with intent to conform and values of universalism and social justice.

Shortly after this reflection one of her children notified her of their deportation. Against the advice of the school Chris explained to the children what was happening. However, she prompted the idea there was nothing they could do to help their friend; this was German law and could not be changed. Chris then set an instruction and said, ‘Rules cannot be changed we have to continue on with our work’. Yet the children’s values of benevolence and universalism floated in the air. Chris heard the children whispering how they could get their friend back. Upon hearing this Chris reflected on her unconscious values. I am asking the children to question power but instilling conformity. I have emphasised the importance of these values I have to follow through. Chris enlisted the advice of a lawyer to see if the child and family could come back to Germany. She fought hard for the children’s values to be upheld. Chris followed the lawyer’s advice and made a plan against the school’s wishes. Before proceeding, was there anything he wanted from Germany? The boy replied, ‘my friend’. There were more hurdles for Chris to overcome but she did, and the teacher and the boy’s friend travelled together to the child’s hometown. On this 10hr journey Chris nurtured the children in Germany’s sense of security and broadened the children’s learning geographically, demographically, socially and culturally by bringing with them a little toy fox to tell the story of their trip. Chris brought their worlds closer together with letters from the children back in Germany awaiting his return. On return with the family a presentation was held for the family. Politicians were asked to join the celebration. Chris taught the children about the value of conformity from a different perspective of the community, noting if they tried to deport the family again everyone would know the family and they would have the backing of the community.

Vignette from Chris Carstens (All means All participant)

Throughout this journey, Chris navigated the fear of losing her job while striving to improve her school system. From a values perspective, it is evident close connections between values, vices, rules and laws as well as emotions exist. Whilst both rule-led and values-led pedagogies are underpinned by values, perspective is often nuanced. This real-life complex scenario started with the children’s values becoming more visible and Chris advocating against her own teacher training, forcing her to question her own limitations regardless of a person’s or system’s status or power.

Next, we move from the process to the individual, the second P (Person) of Bronfenbrenner’s and Morris’s (2006) PPCT model. There is continuous overlap in the model, linkages are consistently made between P, P, C, T between the individuals and the processes over time.

Where are individual values framed inclusive educational practice?

Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2005) stressed the power of the individual acting? within a bi-directional education system (both young children and adults). Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) also viewed? individual traits as personal and resource characteristics which drive personal behaviour to either positive or negative interactions (Hayes et al., 2023). Crucially, we need to critically reflect upon the implications for labelling positive and negative characteristics, particularly as all behaviour is values-laden? Bronfenbrenner and Morris theorised how an individual perspective (or behaviour) had an effect on relational engagements, habits and norms. Simply stated, values can be guiding principles for individual or educational settings. In addition, habits also reinforce values, possibly by developing an evolving disposition that influences the acceptance or rejection of certain ethos. All values have their value (Sheldon, 2019), yet within these overarching categories, they are often driven by individual processes and complex relational values.

Explicitly stated, espoused values are claims of actions. The implications of individual behaviour patterns could result in? people seeking espoused values and values in use. Practices and norms that are possibly hierarchical and are prioritised to be upheld. Experiential work may result in an imbalance between the values-in-use narrative compared to the applied? practice to the espoused values and missions of the educational setting? These disparities can occur for several reasons. The case study below emphasises an individual’s espoused values to the behaviour of the values-in-use. The actions, practices and virtues can include or exclude a person. Values can be viewed from the perspective of? conflicting or espoused values within the educational setting.

Example – What’s my Cup of Tea?

My own individual values lie heavily in relational pedagogy; they are focused on personalised care and education. I support the need for relational agency from birth. As educators we are a safe person the babies could trust and be free to explore also in times of need, they could seek comfort and responsive caregiving. Babies have the opportunity to make decisions about their learning and development to instil in them the right to decide and problem-solve. This did not come without challenges when we had to slow down and move at the baby’s pace rather than outcome led agendas. Trying to enact my values in my day-to-day practice could be a real struggle. My values are conflicting with apparent inclusive child-led policies and regulations. Depending on the educator’s temperament, values and dispositions, trying to work relationally in the presence of outcome-led processes can essentially de-skill the professional graduates’ practices.

Vignette from authors practice: Lydia Murphy

This vignette highlights the importance of instilling an ethical balance between espoused values and the values in use in individual student teacher training. It is crucial to manage the balance of social power for voices which are often overlooked and unheard. Values can be a fruitful conversation, which can be linked with individual identity (Espedal, 2022). Bronfenbrenner (1979) advocated that all the human and nonhuman objects and symbols have agency in reciprocal relationships. From here it is fitting to transition to the third section of the PPCT model: the context.

Values in Context

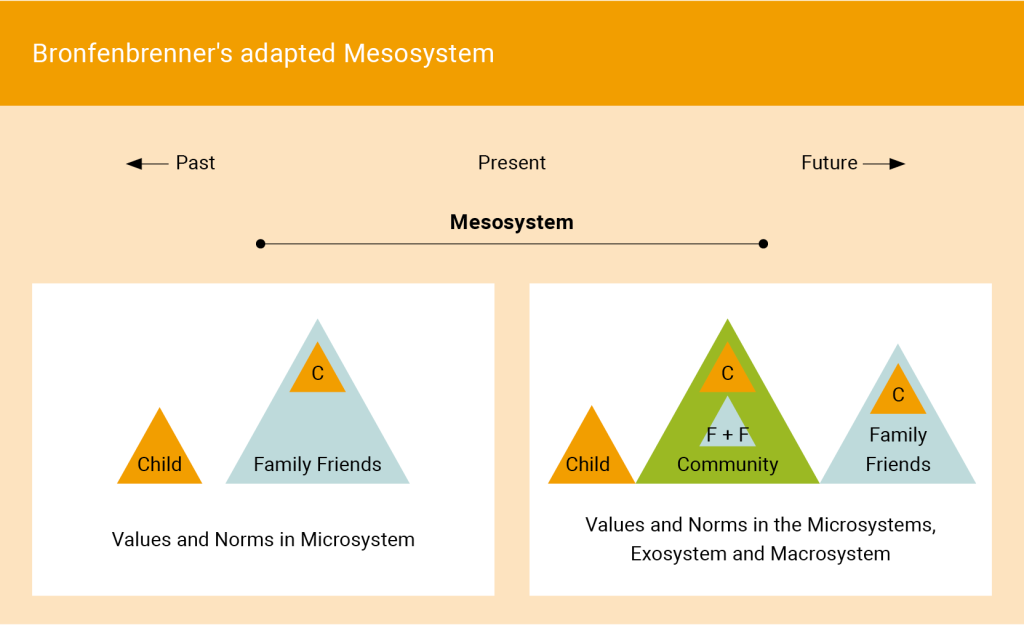

Bronfenbrenner (1979) stated that social strengths and social struggles are not created in a vacuum. Indeed, humans do not evolve in isolation (O’Toole & Hayes, 2019). Bronfenbrenner (1979) advocated for the importance of context in neighbourhoods and communities, and how the environment shapes individuals’ learning and development. This next section focuses on the additional influences of context adding to the analysis in the PPCT model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2005). The chapter → Neuroinclusion: A school community approach displays the full impact of the Ecological Model in communities. This chapter will use the mesosystem to highlight the importance of linking, relating, or unravelling of values that shape contexts in communities. To ensure clarity of the mesosystem, Figure 5 below has adapted Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological System.

The Mesosystem is defined as the communications or interactions in contexts that happen between the microsystems (Hayes et al., 2023). This section focuses holistically on the child as an active participant moving forward and back through the Mesosystem. The orange triangle below represents the child connecting and relating within their home and community over time. The child’s direct and indirect engagements, connections and influences with different community contexts are also said to impact and shape learning and development. Bronfenbrenner developed the term “linkages” for this process of movement.

Figure 5: Bronfenbrenner’s model of ecological system

The flourishing of the child is more likely to occur when the adults in the environment value the voices of the children, and communicate effectively with the linkages across microsystems in the form of a whole community approach (Hayes et al., 2023). An effective communication approach is to prioritise the child’s? voice as a way of being in our relationships. Both arrows represent reciprocal relationships over time between the systems. When we support the plurality of values, this can be viewed as the beginning stages of love and care (Kaur, 2020). The vignette below represents Lilly’ community context. Lilly is a capable, competent little learner. At one and a half years old, she carries her learning across context into a different environment. However, the difficulty arises when Lilly’s competencies at home are valued but her knowledge is questioned within her community context, and viewed through the lens of a whole systems approach..

Example – Learning across Contexts

Lilly is a one-and-a-half-year-old toddler, and values traditions possibly influenced by her family. The tradition she knows well is birthday parties that include having a cake and lighting candles on top of it. Lilly is competent that she knows that when candles are lighting, they usually get blown out. However, when Lilly and her family go to another traditional ceremony the customs change. Lilly is being christened in a church and during the ceremony the priest lights a candle. Lilly brings her learning and competencies across the Microsystem into a different context. However, in this environment candles do not get blown out. The behaviour that stems from the same value can sometimes vary depending on the context. Behaviour associated with the value type tradition, as shown in Table 1, is motivated by the commitment and the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide for the self. However, in the microsystem of her family, Lilly had learned behaviour that did not align with the customs of the new context of the church.

Vignette from research relationship

These diverse value linkages between contexts possibly reshaped Lilly’s self-assurance. Yet, Lilly did not do anything wrong because the candle will be eventually blown out. If customs and rules were prioritised over values in this situation, one could argue that she did not show the right behaviour. However, seeing it from a value perspective, at both times Lilly valued tradition. Finally, the chapter moves to the last section of the PPCT model: the influence of values, patterns and norms over Time.

Values over time

This section is the final in Bronfenbrenner’s and Morris’s Model (2006) which explores Time; past, present, and future. The important addition of time was later added to the ecological system and named the Chronosystem. Bronfenbrenner noted the significance of time and over time on all the layers of the ecological system micro-time, meso-time, exo-time and marco-time. Our values, actions and norms are ever evolving in the present time. Value research suggests that even though values are relatively stable, they often change over the life span, and during periods of transitions and major live events (Bardi & Goodwin, 2011; Döring et al., 2016). For instance, during COVID-19 in 2020, security was a value given high importance. People engaged with family and friends very differently to what we do now. However, some practices and learning could persist from this time. The lifespan can also prioritise different values (Döring et al., 2016). Individual value change over time can be and particularly at an organisational level?

This section develops a political agenda espousing values of universalism and security in organisational agendas over time at a macro level. However, espoused political values in practice highlight values of power and conformity. For example, Equal Start is a government funding model that supports early years services over time to support disadvantaged children’s learning and development.

‘Strand 2 of Equal Start will provide child-targeted measures – measures that are available in all settings and that will focus additional supports on children from disadvantaged backgrounds and priority groups, including: Children living in a small area assigned as deprived under the Pobal HP Deprivation Index. Children from a Traveller or Roma ethnic background. Children availing of the National Childcare Scheme through a sponsor referral, children living in homeless accommodation, and children living in an International Protection Accommodation Centre or Emergency Orientation and Reception Centre’ (DCEDIY, 2024).

Early start is premised on the United Nations Convention for the Rights of the Child (1989) which states that every child has a right to an education. Despite this, the gap in education for children in the most vulnerable areas is widening due to lack of funding and resources. In Ireland, early childhood care and education settings in deprived areas have been running at a loss for over half a decade, leading to carers and families filling the gap. Consequently, many children are unable to attend the setting for required number of hours, as families could not afford the fees. This situation threatens inclusive education, as children are denied access if their family cannot afford the fees. In 2024, early childhood settings continue to see many children experiencing inequality as babies, toddlers and young children remain under-served in their communities. Bronfenbrenner’s and Morris (2006) PPCT model supports the idea of the complex threading of shaping environments and human behaviour. This section presented Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s (2006) PPCT model which emphasised the importance of values where reciprocal relationships are being created in environments and communities. We will now focus on physical environments ?

When designing values …

When investigating the different embodiments of values, we can distinguish many dimensions within which they are regularly shared, negotiated, reproduced or transformed. In educational systems, for instance, we can assess the presence of values within the international and national educational policies, institutional levels and the micro dimension of each teacher’s professionalism (Prichard et al., 2018). As a consequence, values within educational systems could be viewed as the result of complex interactions between multiple agents of different natures and at different levels. This is particularly the case if we consider education as an “open system in which elements are interacting with themselves and their environment in emergent, adaptive, and self-reflexive ways” (Schuelka & Engsig, 2020, p. 6).

However, identifying the dynamics underlying this multitude of spaces in which values dwell, and are exchanged, can be complicated. On closer inspection, we might see how we can consider those levels as specific (but interconnected) contexts. The common thread that links? different contexts would be represented by human agency, which plays a primary role in defining them. In other words, people, through their actions and interactions, in their roles and positions, contribute to the shaping of the environments they inhabit. This act of defining or shaping could be considered – quite interestingly – as an act of design.

We can interpret designing as an activity of reflective and creative thinking that leads one to imagine what does not yet exist, whether we are talking about tools and products, services and processes, symbols or whole systems (Nelson & Stolterman, 2003). As we define design as an activity of envisioning and ideating something for a specific purpose (Redström, 2017), it also inevitably represents a device through which values are communicated and spread between people (Buchanan, 1985). Indeed, design could not unfold in a totally neutral way (Van Gorp & Adams, 2012; Norman, 2004), as “people engage in design in order to devise and implement a new system, based on their vision of what that system should be” (Banathy, 1992, p.41). In this sense, design represents a powerful channel through which we can communicate and spread specific values. We might notice how design does not only refer to domains such as architecture or engineering, as “almost everyone is designing most of the time – whether they are conscious of it, or not” (Nelson & Stolterman, 2003, p.1).

When establishing the rules of a community, sketching the layout of a physical space and planning how to conduct a lesson we are designing, and we are infusing our personal values into concrete actions and fixed structures, offering them for other people to experience in a variety of ways. Design, as an art of thought, would involve the vivid expression of values and ideas about social life (Buchanan, 1985).

Consequently, our actions as professionals of education can potentially contribute to the maintenance (or revolution) of a specific educational system, through the promotion of values and visions. In this regard, if education is crucial for social continuity and the transmission of ideals, hopes and standards for social life (Dewey, 1916), designing education means offering contexts in which knowledge, skills and experiences can be negotiated, renewed and co-created with learners for our future society. This is especially significant when considering that, in specific contexts, promoting inclusion requires contrasting social injustice through transformative processes. In these cases, designing education means co-creating opportunities for liberation and social change (Freire, 1970).

Given that humans can shape contexts through design, how can such designs communicate values that promote inclusion? Understanding design principles and practices is crucial to identify the relationship between each individual’s values and the promotion of inclusion within the different contexts which we take part in, including the educational ones.

Design, values and frameworks

On a broader level, values can be found within the structural frameworks and policies that regulate specific systems. Indeed, values and laws are reciprocally connected, especially as juridical norms descend and draw inspiration from social norms and social values. Such values would be shared between members of a community, constituting their heritage of ideal references and orienting their behaviour. Consequently, social values, which are culture-related, determine social norms and, lastly, juridical norms (Pocar, 2010; Gulotta, 2002). The frameworks that regulate educational systems vary across societies, and are strictly connected to students? rights, designing how education is functional and to be promoted, and carried out, within each specific context and embodying values of different nature.

Enshrining the right to education in international laws and normative tools ensures the adoption of a shared vision on values that are functional, as a means to orient educational policies and practices across communities. From an international perspective, inclusion in education has been interpreted through a human rights-based approach, which is centred around the need to ensure basic human rights and fundamental freedoms to all people (Gordon, 2013). Article 26 of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) outlines a number of primary values that should underline educational practices, such as equality in access, and promoting each student’s personal development and potential. UNESCO’s Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) was designed to guide the right to education, whilst also identifying standard-setting instruments in education (Gros-Espiell, 2005). Similarly, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015) aims at removing barriers to participation, ensuring quality education and learning opportunities for all people. The Index for Inclusion itself (Booth & Ainscow, 2016), as outlined earlier in this chapter, also proposes a set of values to support the promotion of inclusive processes within schools.

The aforementioned sources are just a few examples of how values, rights and regulations are intertwined and describe specific lines of action for the achievement of inclusion within educational contexts. However, it is important to note that, beyond universal and international values, countries and communities adopt specific norms, oriented towards the protection of individual and collective rights, and reflecting a specific set of values which are considered important. Accordingly, the idea of inclusion itself can be interpreted through specific rights and values, leading to a variety of ways which societies can advocate for. As educators, it is crucial to navigate the diversity of these scenarios and understand how intercultural dialogue is needed to reach a deeper understanding of inclusive values. In this way, international cooperation can foster empowerment, dignity and reciprocity among actors, identifying shared languages and envisioning shared advancements with the sensitivity of ensuring a true dialogue and not a subtle continuation of western dominance (Taddei, 2017).

Bigger picture frameworks act as boundaries within which smaller agents act. Accordingly, identifying the values which an educational system intends to promote, allows it to strengthen its cohesion through the contribution of all those concerned (for instance, aligning the actions of teachers and families). Conversely, it can also give space to change, and in doing so, overcome structural injustices and renew the societal purpose and meaning of its lines of action. These possibilities become feasible only when the values at the heart of system are recognised. What are these values and do they protect diversity and promote inclusion?

Such actions assume paramount importance when assessing the presence of multiple agents that, intentionally or unintentionally, communicate and spread a multitude of values based on specific interests and reasons. When considering contemporary scenarios, the plurality of non-formal educational agents and contexts (i.e., social media) may result in communities being exposed to conflicting or discriminative messages (Frabboni & Minerva, 2001). To ensure the development of more inclusive societies, formal educational agents should take part in a shared design based on an integrated educational system both on at an institutional and cultural level, thereby forming a “pedagogical alliance (…) practising neutral, ideal and democratic educational models” (Frabboni & Minerva, 2001, pp. 508–509). It is important to note that such actions, interpreted as “north stars” perspectives, might not be fully realisable, but do act as guidance for the promotion of virtuous processes. Once again, the definition and sharing of values lies at the core of the maintenance or transformation of educational systems, through the design of policies and practices that should regularly be interrogated in order to assess their contribution to the promotion of inclusive education. As outlined at the beginning of this chapter, a dynamic, flexible, and continuous reflection on values is essential.

Design, values and practices

If educators’ agency is guided by the trajectories drawn by bigger frameworks of values and regulations, individual responsibility in promoting values is still prominent at the school or classroom level. The creation of more inclusive learning environments emphasises the role of design as a practice that intervenes in the everyday life of people as an experiential mediator (Norman, 2013; Verbeek, 2008). If design is a reflective process of analysing a situation and defining solutions through continuous improvements and iterations (Schön, 1983), the profession of teaching cannot exclude it from its approach and everyday practices.

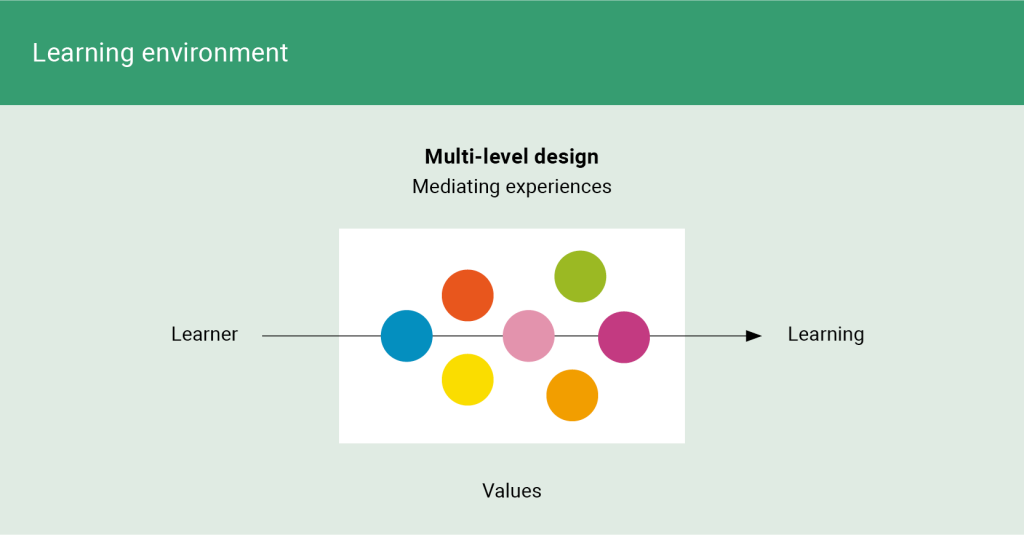

Design in learning means setting, defining or transforming the educational context, and influencing (but not determining) how learners will learn by providing opportunities, facilitators and barriers. At this level, design means structuring the learning environment and setting a variety of environmental factors that can facilitate or hinder learning, and embodying and conveying values. As the focus is centred around the role of educators in designing inclusive contexts, it is important to acknowledge how values within contexts are negotiated by all actors involved. In this sense, learners’ values will be dynamically interacting among each other and also with the values promoted (consciously and unconsciously) by educators and institutions. Figure 6 illustrates the dynamic intersections that emerge when considering values in learning environments, highlighting the role of design in mediating learning experiences.

Figure 6: Relationship between design practices, values and learning  When recognising the power of design in shaping contexts and potentially increasing or decreasing their level of inclusivity, it is essential that any approaches incorporate inclusive values, and embrace inclusive learning environments. In this sense, Universal Design (UD) represents a framework of action that aims to extend the inclusivity of products, services and contexts to all people beyond differences based on personal characteristics (with an intersectional understanding of inclusion) (Maisel & Steinfeld, 2012; Connell et al., 1997; Mace, 1985). As an extension of such an approach in the educational dimension, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) will be later presented as a context-specific approach. To further show the connection between design and values, UD itself is based on a set of principles that aims at ensuring its operability across multiple contexts, such as equity and flexibility in use, or simplicity and intuitiveness in use (Connell et al., 1997). Such principles can guide educators in promoting inclusion from the design of didactic materials or settings to the choice of which activities to be carried out can be offered during a lesson.

When recognising the power of design in shaping contexts and potentially increasing or decreasing their level of inclusivity, it is essential that any approaches incorporate inclusive values, and embrace inclusive learning environments. In this sense, Universal Design (UD) represents a framework of action that aims to extend the inclusivity of products, services and contexts to all people beyond differences based on personal characteristics (with an intersectional understanding of inclusion) (Maisel & Steinfeld, 2012; Connell et al., 1997; Mace, 1985). As an extension of such an approach in the educational dimension, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) will be later presented as a context-specific approach. To further show the connection between design and values, UD itself is based on a set of principles that aims at ensuring its operability across multiple contexts, such as equity and flexibility in use, or simplicity and intuitiveness in use (Connell et al., 1997). Such principles can guide educators in promoting inclusion from the design of didactic materials or settings to the choice of which activities to be carried out can be offered during a lesson.

As contexts play a primary role in influencing our functioning (WHO, 2007, 2001), defining values as contextual factors is crucial in determining the Quality of Life of learners and their level of participation (Del Bianco, 2019; Giaconi, 2015; Schalock & Verdugo Alonso, 2012, 2002) and the meaningfulness of their experience in education (Ghirotto, 2018). Additionally, Universal Design approaches can play a significant role in contrasting discrimination and exclusion phenomena (Sanford, 2012; Imrie, 2000; Connell & Sanford, 1999). The dynamic relationship between design and values is even more central in learning when considering school as a multi-faceted place combining the provision of opportunities for learning transmission of knowledge as well as the provision of opportunities for social interaction, self-expression and growth (Corona & De Giuseppe, 2015) (see chapter “Participation of children and youth). Designing the learning environment requires an understanding of the multitude of variables that can contribute to inclusion (Cottini, 2019; Sibilio & Aiello, 2015).

Managing values in the design of educational contexts necessitates that equal opportunities and the protection of rights within the framework of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), embodies UD in education in order to support such actions (Rose et al., 2014; Izzo, 2012; Rose & Meyer, 2002). As the construct of inclusive education includes the affirmation of core principles as well as the organisation of contexts and procedures to promote inclusion, (Cottini, 2017), UDL can constitute a theoretical reference to orient such activities. As a construct, Universal Design for Learning encompasses three main trajectories (CAST, 2011):

- Offering multiple means of representation;

- Offering multiple means of expression;

- Offering multiple means of engagement.

When considering the design of multiple means of representation, educators should recognise how the knowledge that is shared and co-created with learners can also be communicated through different sensory channels as a means to promote accessibility, personal significance and understanding. In the design of multiple means of expression, students can decide how to share what they learned and the knowledge they built, following their preferred approach. Lastly, the design of multiple means of engagement can increase learner’s motivation (Cottini, 2019). Indeed, such strategies can embrace learners’ diversity in participating in the learning environment (Meyer et al., 2014).

The design of the learning environment is further embedded in values which have a direct influence on active participation and protection of rights. In this sense, design principles and practices can represent key resources to implement inclusion-oriented values, which are essential to ensure meaningful learning and participation opportunities for all. Such a renewed sensitivity to values, agencies and contexts constitutes a conceptual and practical way to foster the promotion and renewal of inclusion.

In other words, if “we were created by the world we live in” (Gibson, 1979/1986, p.130), we may as well reflect upon what kind of world created us, and what kind of worlds we wish to co-create with our learners. The next section delves into the practical applications of such perspectives for our present and future worlds.

How can I work with values to foster inclusion?

Inclusive education means creating equitable opportunities for all students (DEI, 2016). The role of values is at the heart of this process (Espedal et al., 2022). Values as guiding principles underlying inclusive cultures (Booth & Ainscow, 2016) can ensure that the progress of this path is sustainable and ensures inclusive education is empowered and expanded at various levels. A recent study by Döring and her colleagues (2024) highlighted how teachers and educators instilled values using diverse methods across different aspects of the school environment. They further argued that the role of teachers extends beyond education to fostering democratic values, attitudes, and beliefs, contributing to a more inclusive and sustainable society. Values education is increasingly emphasised globally in Europe. For instance, some Teaching Standards focus on promoting respect, honesty and trust in children, aligning with professional ethics and integrity. Even without formal guidelines, schools are never devoid of values, and spaces exist where learning and experiences are shaped by a clear mandate, with every teacher, consciously or unconsciously, representing certain values (Schubarth, 2019).

Educating children is not just about values or teaching them values, but it also concerns our own values and how teaching and learning embodies values? as has been stated above (Schulz von Thun, 2015; Wocken, 2013). How can we, as teachers, work with and on values in our classrooms on a daily basis? Within the following section we argue that four trajectories might be key value-based ways to foster inclusive education; reflection, resolution, negotiation and reinvention. These separate components are divided into individual threads for knowledge application. However, in practice these trajectories are completely embedded in and braided through each other.

Reflection

One of the fundamental trajectories to supporting values is reflection, as this enables us as teachers and educators to continuously examine our own professional work and experiences, and to discern which perspectives are central, and which are peripheral, as well as clarifying and identifying the core values (Brookfield, 2018). By being more aware of our personal values and beliefs, and what is important to us, we can understand how values can help us to achieve reflection? (Schön,1983). Regular reflection can reveal how well we align with our values, but can also identify where potential conflict arises. We must also consider the extent to which these values are influenced by our experiences, background, and cultural context. As outlined at the beginning of this chapter, values are mostly unconscious but guide our behaviour (Schwartz, 2012). Therefore, it is crucial to reflect on what is important to us as part of our profession, both separately and when combining educational and political agendas (O’Toole & Hayes, 2019). The challenge lies in how we align our personal values with the values of the educational environment. We should review our reflections as messy, unorderly and if necessary, adjust again. Throughout this process, it is essential to seek feedback from our colleagues as critical friends, and assess how they observe us and our values in actions. The key point is that contemplation becomes constant practice (Brookfield, 2018).

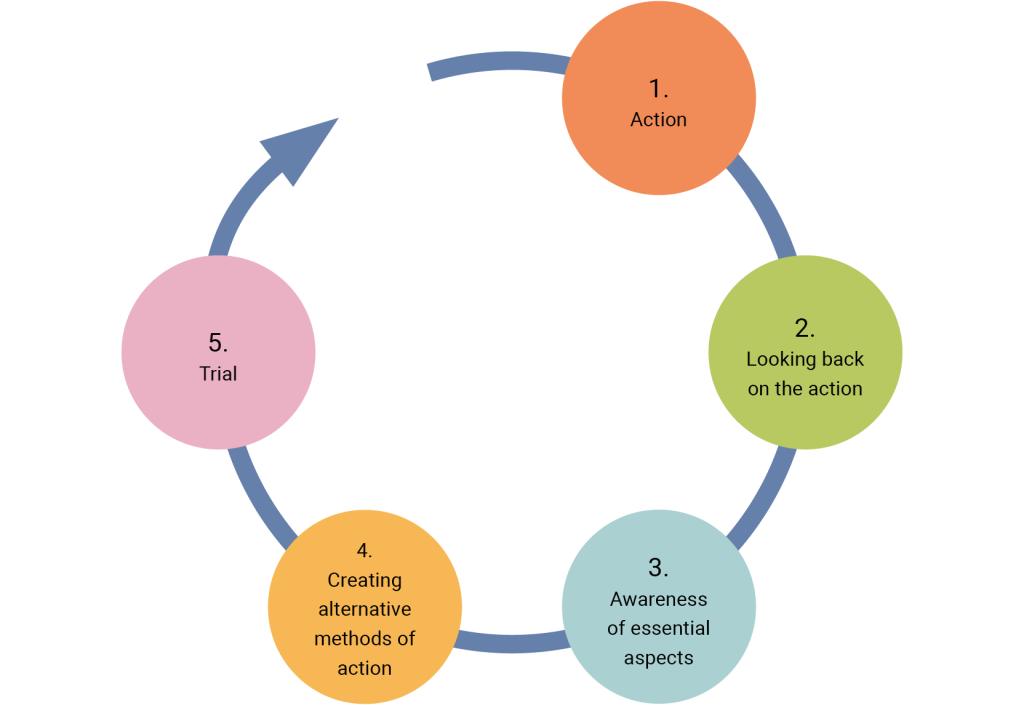

In the early 1980s, teachers and educators recognised the difficulties arising between theory and practice, and reflection was identified as the missing link. Fred Korthagen (1985) , a researcher in professional development of teachers and the pedagogy of teacher education, and the promotion of reflection in teacher education, defines reflection as “the mental process of structuring or restructuring an experience, a problem or existing knowledge or insights” (Korthagen, 1999). He elaborated a model, which describes the process of reflection which he described as ALACT (elaborated in Figure 7 below) (Korthagen, 2001).

Figure 7: The ALACT model of reflection

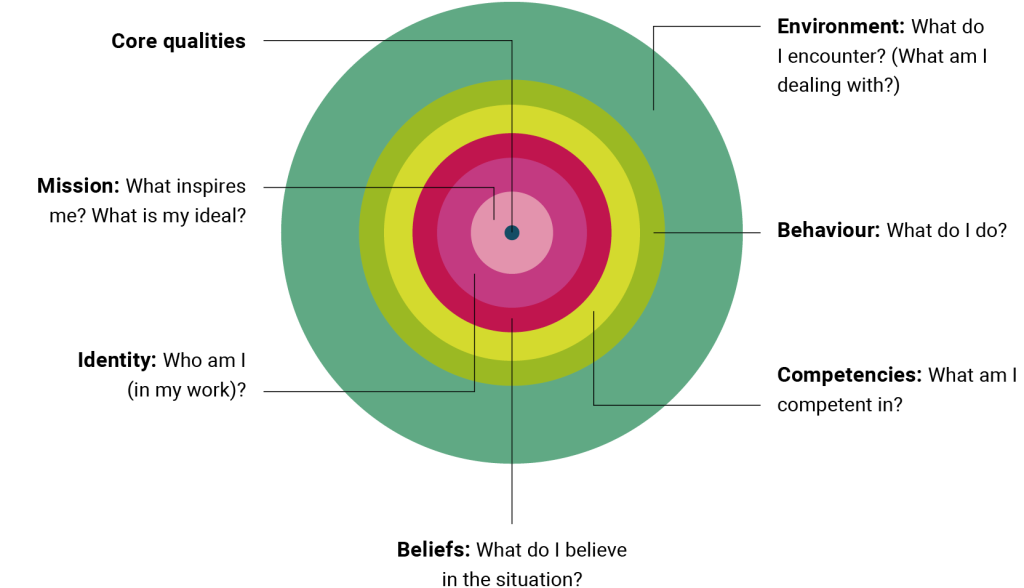

ALACT is still regarded as lacking in profound knowledge and missing empirical evidence. A second model exists which suggests that different levels of reflection, the so-called Onion-model Korthagen, 2004; see Figure 8), provides content related information to ALACT. According to Korthagen & Nuijten (2022), this model differentiates various layers of an individual’s identity resulting in (student) teachers engaging in deeper reflective processes. The process makes it possible to develop a more conscious understanding of personal qualities, and further involves identifying and addressing internal obstacles. The use of this onion model for critical reflection can help to uncover, and challenge, any personal biases related to different aspects of diversity. Therefore, as the authors argue, the approach can be a step towards reducing inequality, combating discrimination, and promoting social justice. Additionally, it may also become a more inclusive method when the student’s voice is captured in the reflection process, Why not also reflecting together with the students (see also the chapter → Person Centred Planning)? Both the ALACT model and the onion model can be a starting point for the reflection of values in the classroom.

Figure 8: The onion model

Some other practical suggestions are also recommended. Holding regular and ongoing teacher meetings are valuable for ensuring the sustainability of the process. These meetings should address the challenges in applying values, practice and feedback from colleagues, parents and children to improve the implementation of values, and, if necessary, to review them. When we reflect on the vignette of Chris’ experience, the critical reflection approach in addition to the dialogue and dialectical method, could assist in finding a solution. How values are incorporated into student interactions, teaching methods, and curricula should be also discussed. New and more effective ways of applying values in inclusive education should also be explored (Palmer, 2017).

Teachers should also provide opportunities with students to discuss perspectives, values, experiences and needs. The classroom environment should be one where students feel secure and confident and where they will be heard without judgement. Giving voice, and influence, to students is vital as participatory action research with children has shown previously (Jörgensdóttir Rauterberg & Hinz, 2024). In this study, children collaborated with teachers? and spoke of their experiences of school and future development school services? Using such a democratic approach would be similarly beneficial for the values approach? (see also the chapter → Democratic schools). Such an environment would also create a space for interaction for students who are introverted, ensuring they feel comfortable and have the courage to express their opinions. When students feel that their voice is heard and that they are valued, the reflective process becomes more meaningful. Students express their values, identity, assumptions, and experiences, and share their perspectives, not only as a standalone activity but also as part of? the curriculum. As a result, we find that the active role of students leads to the creation and invention of new activities (Brookfield, 2018; Noddings, 2003). By instilling values, teachers create a more inclusive learning environment and foster the flourishing of students. Such a transformation, and approach, requires commitment, trust, creativity, and continuity, and lead to the fulfilment of the diverse needs of students.

Resolution

As you read at the very beginning of this chapter, values sometimes can also conflict with each other, in other words, you cannot combine actions motivated by two specific values such as benevolence and power (Schwartz, 2006). However, you can become aware of this competing nature when decisions must be made between both values which are equally important to you. It can also be the case that your values, and the values in the school system, come into conflict as illustrated in the vignette with Chris. Additionally, there may be students who value different values in daily situations of learning in your classroom. Common to all of these situations is the need to find a solution that involves both the teacher and students working together, often in the face of conflict. Resolution involves resolving disputes, achieving consensus, or solving challenges and problems in personal, social, or professional settings (Esptien, 2014). As outlined at the beginning of the Chapter, when it comes to values and inclusion, a dialectic approach such as that proposed by Wocken (2013), could do justice to the complexity of values and their dynamic relationships and help to find a solution on a higher level.

Problem-solving also involves translating ideas into actions. There are numerous ways to achieve a resolution in relation to values. Firstly, identifying core values by reflecting on the topic is a crucial first step. Focusing on our own values is more beneficial rather than expecting others to meet our standards of values, where the latter can result in a more dissatisfactory achievement. Instead of concentrating only on solving problems, teachers can make decisions to set some goals which improve some aspects of their students’ lives (Kennelly & Oke, 2024). Teachers need to be aware that values are not easily changed. Hence teachers should concentrate on the long-term relationships in parallel with possible short-term goals. By focusing on resolution, they make a meaningful approach for growth and change (Kennelly & Oke, 2024).

Problem-solving also requires a commitment and responsibility to equity. This process involves placing values at the forefront of all partnerships. Through the process of persistence, respect and continuity, it can strengthen relationships and the determination of the teachers and students (Epstein, 2014). This process also involves identifying the conflict between personal values and the values of others, and finding possible solutions to these dilemmas. Recognising and understanding different perspectives and exploring common ground are among the solutions. Listening is a basic but profound way to direct those to alternative and creative solutions, whilst also respecting individual’s core values and paying attention to different perspectives.

Negotiation

Since dialogue and negotiation are important pillars of a participatory process in inclusive education, the existence of a dialogue space between students, teachers, administrators, and families is vital. Dialogues that are focused on finding a solution, listening to different perspectives and values of others and clarifying their opinions and experiences, leads to dialectical and peaceful negotiations and helps to identify alternative solutions for possible value conflict situations on a higher level. Strengthening dialogue requires the teacher to be open and receptive to creative ideas in expressing values, avoiding a win-lose approach, and seeking solutions that consider the diversity within classrooms and schools. The necessary skill of active and empathetic listening is useful and accelerates the path to finding a common ground (Espedal, 2022). In a safe environment, dialogue fosters and strengthens self-confidence in the educational environment and increases the transparency of perspectives and values (O’Toole & Hayes, 2019).

Reinvention

Maintaining an innovative spirit in the educational system is a key foundation for inclusive education. Teacher professional development is an ongoing process that benefits from remaining informed about current research findings and techniques on inclusive education. It also involves continuously adapting teaching methods to support students’ development and recognising the diversity present in the classroom. An innovative mindset leads to the elimination of approaches that are no longer effective, which drives growth and improvement in the educational environment, thereby discarding perspectives which are no longer practical and do not advance the educational system (Palmer, 2017). The same approach applies to values. Although this approach may seem challenging and complex at times, it is ultimately an ethical and timely educational imperative that empowers teachers to develop inclusive learning environments. It is crucial to remain open to a changing environment, and to re-examine and re-construct teachers’ responsibilities in inclusive education (Espedal et al., 2019). Consequently, the evolution of knowledge necessitates evolution and innovation. It is important to keep in mind that working with values is a constant process that requires self-awareness, flexibility, discussion skills, active listening, and innovation. An innovative mindset encourages a more flexible approach towards children and adolescents’ diverse life stories, experiences and values, and opens up new perspectives for them.

This approach involving the four trajectories of reflection, resolution, negotiation and reinvention, can facilitate an engagement with values in a continuous and adaptable manner, ultimately promoting inclusive education.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- What is your cup of tea? What is important to you?

- What is important to you as a (future) teacher or professional?

- Does the educational setting reflect its stated values, mission, or ethical practices?

- Do you recall a specific situation where values played a significant role?

- How do values, or how might they, influence your (future) classroom?

- What tools do you have to design the educational environment you work in and how do you use them?

- Are values in your (future) classroom discussed, negotiated, or reviewed over time?

- Imagine a concrete way to reflect on values together with your students.

- How might your practice adapt to accommodate diverse values?

- Could you apply what you’ve learned in this chapter to a university context?

Literature

- The idiom "(not) my cup of tea" means something that a person likes or dislikes. In its positive form it is often used to describe personal preferences, especially for activities, hobbies, or topics someone finds appealing. In its negative form it is a casual way to say something isn’t to one’s liking or interest, often used to politely show a lack of enthusiasm or to decline. ↵

- As you found out in the first digression, behind the same word you can find different understandings, meanings, definitions. Behind the value square you will not find values in exactly the same way as in the Schwartz model. ↵