Section 2: Supporting Inclusion in the Classroom and Beyond

Navigating Inclusive Educational Transitions for All

Silver Cappello; Danielle Farrel; Paty Paliokosta; and Irati Sagardia-Iturria

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“I started attending a local mainstream primary school at the age of 4 ½.

Prior to my first day at school, my parents had to challenge the Education Department in order for me to obtain a place at the local mainstream Primary. At this point it was the Education Department’s belief that my disability would be disruptive for the rest of the class. However, this was not the case. I excelled academically and reached the same milestones as my non-disabled peers.

By the time I was ready to transition to secondary school, the opinion of the Education Department had completely changed. They had previously questioned whether I could achieve academically. Having proved that I could, the Education Department was keen for me to remain in mainstream education. However, due to access barriers at the local mainstream secondary school, I decided with the support of my parents to move to the Special Education school which at the time was the only school of its kind to follow the mainstream curriculum, and this was where I obtained my qualifications.

From here I was supported to attend mainstream college for one day a week to assist me in deciding whether I felt this was the next step for me. I decided that it was, and after returning to mainstream education I went on to obtain a Higher National Diploma in Media Studies, before progressing to university, graduating with my Bachelor of Arts Honours degree in the same discipline.

Despite challenges in finding employment, after graduating I successfully transitioned into employment with the role as a Research Assistant at the university where I studied. During this time, I was presented with the opportunity to return to education and study for my PhD. I chose to do this and completed this chapter of my life in 2015 when I graduated with my PhD. Since then, I have established my own business and now successfully use my lived experience of disability to provide a range of services for individuals and families living with disabilities, businesses and employers seeking to be fully inclusive.

On reflection, I have achieved what I have due to my self-determination and resilience. However, if I did have Person-Centred Planning support sooner that focused on my dreams and aspirations and what support I needed to achieve this, I feel strongly that my educational transitions to date would have been far smoother. However, with the knowledge I now have around this I feel that this will be the case for my future transitions.”

Dr Danielle Farrel, Managing Director, Your Options Understood (Y.O.U.)

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find information on the following topics:

- Transition process and laying the groundwork for meaningful engagement among the team, families, and children.

- Initial Meetings a couple of months before the academic year and enrolment: Families may get familiar with the school through events such as familiarisation days and pre-enrolment. These activities are part of the initial meetings that help families understand and feel at ease in the school setting. During this time, families can also enrol in school.

- First Group Meeting and individual meetings with the family the first days of the academic year: The first meeting allows families to come together as a group and strengthen their ties to the school. Families gain insight into their child’s daily experiences at school, including activities and interactions, during this meeting. It provides an opportunity to address any concerns or questions that families may have. On the other hand, the first individual meeting between families and educators is crucial. This meeting establishes a climate for communication and collaboration while emphasising the significance of the transition. It addresses issues such as physical school environment setup, maintaining a respectful distance, understanding the child’s space and activities, and sharing critical information.

- Preparing for the First Days of School: Careful planning is required for the first days of school. Teachers and educators must make sure they have the resources that they need to meet the needs of both children and families. Exchanging information during drop-off and pick-up times, leaving notes, and making regular phone calls all contribute to creating a good and comfortable environment for both children and families.

- Creating Individualised Connections: To ensure that everything goes smoothly and effectively, it is essential to establish a strong emotional connection between the child and their reference caregiver, which should be as solid as the connection they have with their mother or father but adapted for the school environment. In order to create a secure and supportive school experience, thorough attention must be given to the child and their family. This involves careful planning and organisation of spaces and materials that can assist us in providing what they need. It is crucial to select play materials that cater to the pupils’ interests and needs, ensuring that they are well-engaged. Similarly, the physical space should be arranged in a way that allows for a small space to be allocated for families.

- Respecting Developmental Stages: Recognising children’s developmental stages is critical. Some pupils may still require their baby bottle, while others may have transitioned or never used a bottle. It is critical to recognise, respect, and incorporate these differences into the transition process.

- Providing a variety of areas: It is preferable to provide more than one space, allowing children who do not wish to remain in the classroom to move outside. This can also be a great opportunity for new families to meet in a relaxed and cheerful atmosphere, as well as for pupils who prefer to stay inside the room to do so. Furthermore, a special area can be created to make families feel at ease in school. Placing a sofa, for example, can allow families to take a break from activities while remaining close to their children. This way, during transitions, children can stay in a familiar spot, and families can rest assured that they will find their child in that familiar spot, bringing a sense of calm and spreading a positive influence on the school environment.

- Reflection and adaptation: The transition process is not a one-size-fits-all approach. It requires conviction to interpret how each child and their family feel about the school environment. Finding signs of comfort and security, showcasing initiatives, remaining open to change, and addressing fears and needs without judgement are all part of it. As a result, assessing the transition process should be qualitative rather than quantitative. Understanding how the process unfolds, embracing moments of stillness and progress, and allowing for flexibility and adaptation are all part of the process.

Introduction to Topic

Transition etymologically refers to a change from one state or context to another. One generic definition could be the following:“Transitions are key events and/or processes occurring at specific periods or turning points during the life course” (Vogler et al., 2008: 1).

Key aspects

Overall, as the authors argue, the transition to school is a complex process that involves building connections, understanding each child’s uniqueness, and fostering emotional security. It is a journey that requires careful planning, ongoing communication, and a deep respect for the emotional well-being of both children and families.

On the other hand, the educational organisation Penn State Extension (2020), related to horizontal transitions, explained how the process of transitioning from one activity to another within the early childhood classroom setting can present difficulties. Many toddlers struggle to switch activities as some children can be frustrated when they have to leave something they are enjoying or feel they are almost done. Other children may be confused or worried by transitions. This is usually due to a lack of structure. Other children may not understand why they are being asked to do something else, view the situation as unfair, or be unsure of what to do next. Children handle uncertainty differently. When transitions are unexpected or unclear, they may have frustrated anger, increased anxiety, and this may affect their day.

In this regard, these are some of the strategies that they provide in order to smooth activity transitions and avoid unexpected changes:

- Make a schedule: It is easier to deal with expected transitions than unexpected ones. Explaining the day’s plans and providing reminders about what comes next could be beneficial. As the development of each child will be unique, visual schedules will also be helpful.

- Stick to the schedule but build in transition times: Following your schedule will help children develop routines and expectations. However, flexibility is also necessary in order to respond to children appropriately.

- Let people know when to switch: To reduce schedule confusion and surprises, use verbal and non-verbal cues to indicate when to move to a different activity. Provide warnings, incorporate instruments to signal the next activity, incorporate transition songs and so on.

- Pairs transition: Planning partner activities or asking a child who transitions well to help another child get ready could be another strategy. This should be framed as supporting rather than as a punishment for the child that is struggling with the transition.

- Think positive: Transitions are challenging, especially for young children who might struggle to understand your expectations. Experiencing frustration during transitions makes it more difficult for your children. Children often mirror your emotions. During transitions, children will pick up on your composure and appropriate behaviour and attitudes.

From early childhood to primary school

The Transition: A Positive Start to School Resource Kit (DET, 2017) was designed by the Victorian Educational department to provide current, research-based, and practical advice. This guidance is intended for early childhood professionals who work with children and families during the critical school transition period. This Kit comprises of six sections. The first section offers an overview of the significance of a positive transition to school, covering transition contexts and effective practices. Sections 2 through to 5 detail vital elements of successful transition strategies, such as fostering relationships, addressing equity and diversity, ensuring learning continuity, and planning for transitions. The final section, Section 6, outlines practical tools for supporting effective transitions, including the Transition Learning and Development Statement, alongside various assessment, and planning methods. These are some of the strategies that are provided for smooth school transitions:

- Foster respectful, trusting, and helpful relationships with children and their families.

- Establish mutually beneficial connections that actively encourage the exchange of pertinent information and its value.

- Create professional roles and collaborations that promote ongoing reflective practice.

- Recognise the agency of children and their role in transitions.

- Respect the cultural histories and heritage of all individuals involved in the transition process.

- Recognise the assets and abilities of all participants in transitions by setting high expectations and committing to fairness.

- Utilise approaches that are adaptable and flexible to the diverse family contexts within local communities.

- Provide appropriate and ongoing support to educators, teachers, children, and families.

In terms of relationships, Dockett and Perry (2005) participated in a special project, called ‘buddy programs’, in two schools in Sydney, Australia. 25 students studying to become teachers and 130 children in Year 5 took part. These programmes pair older students who are familiar with the school with new students who are just starting. It helps new students adjust and lets older students show they care about their school. They all attended special training days to develop communication skills, reflection, and community building skills. Through interviews, the researchers find out what concerns the new kids had and how they could help. These provided the basis for the development of ‘training’ experiences by the teacher education students and also the evaluation of the program.

Following with the same authors, they developed an instrument over a 20-year period, and it has been utilised in multiple ways in both research and practise in a number of regions. The Peridot Education Transition Reflection Instrument serves as an instrument for documenting and leveraging the findings of a school program evaluation, facilitating reflection on existing programs and the formulation of future ones (Dockett & Perry, 2022: 177-180). It relies on the four components outlined in the position statement: opportunities, aspirations, expectations, and entitlements. Each position statement comprises four tables illustrating four levels of achievement for each of the four key stakeholders: children, families, educators, and communities. This set of tables empowers partners to make informed assessments based on evidence for each of the constructs (see table 1, 2, 3, and 4 in appendix).

From primary to secondary education

An English research project explored the practice of a Transition Club with a sample of 38 students (Humphrey & Ainscow, 2006). It was a pilot project for a group of students who had underachieved in maths and literacy at the end of primary school. Data was collected through participant observations, questionnaires, and a focus group interview. Transition Club took place over a six-week period towards the end of the summer term (at the end of the last year of primary school). In each week students spent 3 days at the secondary school and 2 days at their primary school. This exploratory project was successful in providing students with a sense of belonging, helping them to understand the secondary school structure, and making learning fun. This practice revealed interesting results highlighting what vulnerable student groups are concerned about. The study showed that new expressions of inclusive practice typically emerge in a collaborative situation rather than working alone. Furthermore, innovative educational practices can help in facilitating students’ social and psychological adjustment to the new school with a sense of belonging, orientation, and enjoyment.

The ‘STARS’ research study, conducted at UCL and Cardiff University, aimed to understand how to facilitate a successful transition for children from primary to secondary school. Over the course of the study, approximately 2000 pupils from South-East England, UK were tracked during this transition. Information from pupils, parents, and teachers was collected to assess well-being, academic progress, and their experiences with school and relationships. The study established two key aspects of a successful transition: academic and behavioural engagement in school, and a sense of belonging. These were measured using the ‘START’ questionnaire completed by primary school teachers. Most children had initial concerns about moving to secondary school, which gradually lessened after starting. However, worries related to friendships, discipline, and homework took more time to subside. Friendships underwent significant changes during the transition. Parents were found to have insight into their children’s transitional needs. Vulnerability to a poor transition was not linked to a single group of children; rather, various risk and protective factors influenced the outcome. Therefore, an effective approach to support pupils during transition might involve general strategies to address common concerns, with additional, personalised strategies for vulnerable individuals based on their specific needs. Primary and secondary schools employed different strategies to support children during the transition. Systemic strategies, like building connections between the two school levels, were effective at reducing school anxiety. Several secondary school practices promoted academic progress in Year 7. These strategies were well-received by teachers, suggesting their high acceptability. Furthermore, secondary schools implemented various practices to aid pupils in forming friendships, as this remained a persistent concern. The questionnaires, resources and the report of the research can be seen here.

From secondary education to further and higher education

In Spain, the Red SAPDU (2020) highlights a concerning trend where many students with SEN do not progress to higher education beyond compulsory schooling. Limited statistical data availability makes it challenging to compare various SEN student groups between non-university and university settings. Recent data indicates a significant drop in SEN students transitioning to university compared to those who enter high school, potentially due to the demanding educational journey they face. This gap emphasises the need for a transition guide to facilitate higher education access for SEN students. The Red SAPDU (2020) created a practical guide to aid departments, support teams, university services, and various stakeholders in enhancing SEN students’ access to higher education. The guide serves as a dynamic tool and should be regularly updated within the SAPDU Network.

The guide encompasses the following aspects:

- Support Structures in Universities: Nine out of ten services offer personalised guidance to SEN students, bridging communication gaps between students and faculty. They uphold legal rights, advise on best practices, and suggest improvements. Disability-specific recommendation guides are also available.

- SAPDU Network: Created in 2009, this network unites technical staff from disability support services in around 60 Spanish universities. It operates under Crue-Asuntos Estudiantiles, a sectoral commission of Spanish Universities. Working groups focus on topics like curricular adaptations, employment, mobility, communication, and ICT. The network fosters information exchange, best practices sharing, and collective decision-making.

- Transition, Access, and Welcome (TAA) Model: This model ensures smooth NEAE student transition to university. It involves support programs from pre-exam phase to successful university integration. Key elements include vocational pathway guidance, collaboration between support services and secondary schools, stakeholder involvement, and collaborative adaptation implementation during university entrance exams.

- University Entrance Exams: Adaptations for SEN students during entrance exams are determined with input from educational guidance departments and education administrations. These adaptations build on previous curriculum adjustments, ensuring fairness and accessibility.

- Welcome Process at the University: Before the start of the academic year, accommodations are made for physical accessibility and communication. Personal support, resource acquisition, academic support requests, and more are addressed.

- Support Services in the University: These services provide information, guidance, and advice on rights and resources. They collaborate with exam committees and process support requests. They offer advice on curriculum and assessment adaptations, provide individual tutoring, and promote inclusion through activities and awareness initiatives.

- Non-academic Tutoring Action Plan: Tutors offer support and guidance for the holistic development of students. They provide information, monitor academic progress, offer solutions, and facilitate transitions.

- Technical and Material Resources for Accessibility: These resources include an assistive products bank, virtual platforms, universal accessibility tools, and communication tools to ensure equitable education.

- Scholarships and Grants: Financial assistance is available for SEN students to facilitate their higher education journey.

- National and International Mobility: Universities offer resources for mobility, enhancing students’ educational experience.

- Internship and Employability: Efforts are made to provide SEN students with opportunities for internships and enhance their employability prospects.

Involving family and ensuring effective coordination between administrative structures and services are essential for SEN student success. Overall, the guide aims to empower SEN students in their journey toward higher education, offering a roadmap for inclusivity and accessibility.

From secondary school and university to the employment sector

As the OECD (2022) states, the transition from education to the workforce is influenced by various factors, including the duration and quality of schooling, labour market conditions, economic environments, and cultural contexts. While some countries adhere to a traditional sequence where individuals complete their education before seeking employment, others have concurrent systems where education and employment occur simultaneously. Gender disparities in this transition are evident across different nations, with significant proportions of young women facing challenges in entering the labour force.

During periods of unfavourable labour market conditions, such as high unemployment rates, there is often an incentive for young people to prolong their education to acquire additional skills. This extended investment in education can serve as a strategic response to unemployment, contributing to future economic growth by aligning individuals with the skills demanded by the labour market. Moreover, providing support to employers through incentives to hire young people can facilitate smoother transitions from education to employment.

The absence of employment can have enduring consequences, particularly for individuals experiencing prolonged periods of unemployment or inactivity, leading to discouragement. Notably, young people not in employment, education, or training are a significant policy concern due to the negative impact on their labour market prospects and long-term social outcomes. For this reason, it is considered important to identify social and economic inequalities that sometimes are overlooked. Some of the policies or incentives that are carried out prioritise the need of employers over the well-being of the workers. Advocating for policies that prioritise equitable access to education and employment opportunities may address structural barriers. By embracing a more inclusive and socially conscious approach, we can create a fairer and more resilient economy that benefits everyone, not just some privileged ones.

An example of creating inclusive social economy business, as it is stated in GUREAK (2024): “GUREAK is a Basque group of companies which generate and manage steady work opportunities, suitably adapted, for persons with disabilities, with priority for people with intellectual disability in Gipuzkoa. It is a diversified group, mainly active in the industry, services, and marketing domains”. Throughout their commitment to social responsibility and inclusive practices, they strive to make a positive impact on both the economy and society.

➔ From mainstream school to special settings and vice versa

Parents and educators should consider several parameters when planning such transitions, including:

● Individualised support to the specific needs and abilities of the child. This support might involve specialised teaching methods, individual education plans, emotional support, such as therapy, or counselling.

● Open, consistent, and constructive communication between parents, teachers, and the child is crucial. Regular meetings and updates can help address concerns and adapt the transition plan as needed with support from a transition support team.

Strategies should be in place to facilitate the child’s social interactions. This may involve:

● peer support

● social skills training

● extracurricular activities.

Modifications and reasonable adjustments (Equality Act, 2010) may be necessary in mainstream or specialised settings to ensure that the curriculum is appropriate and aligned with the child’s abilities and learning style.

The research that is currently being presented is situated within the research project ‘Promoting a Culture of Participation in order to make both the Community and School for all.’ It was carried out by the Zehar and Hazitegi research groups from Mondragon Unibertsitatea between the years 2020 and 2022. The aim was to encourage everyone in the centre to get involved and collaborate as a community. This also involved empowering children and young people to participate more actively in making decisions about the future and the community, creating a stronger sense of togetherness, and ensuring that nobody was feeling excluded. To help students move smoothly from one school level to another (from Infant Education to Primary Education; from Primary Education to Secondary education and between the three cycles of Primary Education), we looked closely at these transitions. We did this by talking to students (through participatory and engaging techniques), families (through questionnaires), and teachers (through semi-structured interviews), to understand what problems they face and how things can be made better. It was discovered that making an action plan for these changes could help reduce worries, adjust expectations, improve relationships between new students and teachers, give helpful guidance and information for families, and ensure good coordination throughout phases. Voluntary teachers, families, and researchers created a transition plan considering all children, family, and teachers’ ideas. After the plan was put into action, the evaluation was made again asking all children, their parents and their teachers about the actions that were carried out, their experiences, suggestions, and areas that needed improvement.

On the other hand, the Armenian study report (Bridge of Hope, 2015) examines the country’s educational transition difficulties and potential practices from the viewpoints of teachers, parents, children and young people, specialised personnel, and other important stakeholders. It examines learners as they go from kindergarten through primary school, then to secondary and higher/vocational school, as well as additional learning options and jobs. It emphasised the crucial support needed for children, particularly those with disabilities and suggested strategies like:

● Appointing transition staff or ‘liaison workers’ in both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ schools to facilitate information exchange and ease the transition process.

● Identifying emotional, behavioural, developmental, or academic challenges by existing staff and conveying this information through an Individual Education Plan (IEP) or relevant documents.

● Completing and sharing IEPs before the transition.

● Organising meetings between upcoming students with disabilities, their guardians, and teachers who will be involved, potentially including home visits.

● Recommending trial/transition days for students to visit the new school, along with friends and family, for getting acquainted with the environment. Acknowledging the necessity for staff training, especially when the new school’s staff requires support for specific identified issues.

Although various strategies and examples are provided for different and specific transition stages, given that transitions are continuous and are an ongoing process, it is believed that all strategies can be applied to each of the transitions, tailoring them to each specific one.

General approaches to facilitate educational transitions

It is important to explore various approaches that support transitions for children and young people across different age groups and stages. Bridging programs can be valuable in assisting students, young learners, and individuals as they navigate significant milestones in their educational journey or broader life experiences. However, when considering these programs and approaches, it is crucial to acknowledge and address the systemic barriers that may impede successful transitions, particularly for those at risk of marginalisation.

When examining individuals in transition, such as young children transitioning from early years to primary education or from home to early years settings, it is essential to adopt a holistic perspective. This entails considering socio-emotional interventions, academic support, effective utilisation of community resources, and multidisciplinary collaboration (Fabian & Dunlop, 2007; Pianta, Cox & Snow, 2007). For example, when working with individuals, it is vital for teachers and educators to establish meaningful connections with relevant stakeholders, ask pertinent questions, and ensure the inclusion of diverse voices.

The concept of “voice” is particularly significant, recognising that very young children may not express themselves in conventional ways, but their needs are valid and must be attended to. Involving families and being mindful of linguistic, social, cultural, and heritage factors is crucial in promoting inclusive practices that involve co-production. Furthermore, in contexts where individuals may experience oppression or marginalisation, employing a relational pedagogy approach is vital (Doane, Hartrick-Doane & Varcoe, 2020; Woodrow & Staples, 2019). This involves equipping teachers and educators with the necessary tools to establish meaningful relationships, which in turn facilitate active listening, genuine co-production, and purposeful planning. These are inclusive practices that empower individuals who may otherwise be marginalised or oppressed.

Student and family voice

Understanding that participation is a key element in terms of inclusion, it is essential to place the voices of children and their families at the centre of the school community. Especially, during transition processes, listening, understanding, and taking into account their experiences, perspectives and identified improvement aspects will be crucial in order to design appropriate contexts for them.

Children and young people are active participants in their educational journeys. By incorporating the child’s voice and perspective, the transition process becomes more child-centred. A method that acknowledges that children have unique and diverse ways of expressing their perspectives and experiences is the Mosaic approach. It is aptly described as “a mosaic- an image made up of many small pieces, which need to be brought together in order to make sense of the whole.” Essentially, the Mosaic approach provides young children with various avenues to express their viewpoints, allowing them to communicate their thoughts using what has been aptly referred to as their “hundred languages” (Clark & Moss, 2005).

This approach aligns seamlessly with the concept of a “pedagogy of listening.” A pedagogy of listening emphasises the importance of actively listening to children’s thoughts and perspectives. It treats knowledge as something that is constructed, and provisional. In other words, it recognises that knowledge is not merely the transmission of a fixed body of information from adults to children but rather a dynamic and context-dependent process (Paliokosta and Kindness, 2011).

A key aspect of this pedagogy of listening is that it respects the individuality and uniqueness of each child’s perspective. It does not seek to make all children the same or impose a uniform set of ideas. Instead, it recognises the diversity of experiences and viewpoints that children bring to the table. It is a way of understanding and valuing the individual voices and perspectives of children, acknowledging that these voices contribute to the rich tapestry of experiences and knowledge. This approach not only ensures that the child’s views are considered but also empowers the child to take an active role in their own transition (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005). The use of the Mosaic approach (Clark & Moss, 2005; Dahlberg & Moss, 2005) and a pedagogy of listening can significantly enhance effective educational transitions for children, young people and their families in the following ways:

- Understanding Individual Needs (Ade, A. R., and Da Ros-Voseles, 2010): The Mosaic approach, with its emphasis on valuing each child’s unique perspective, allows educators and professionals to gain a deeper understanding of the individual needs, preferences, and strengths of each child. This insight is invaluable during transitions because it helps them tailor the transition process to the specific requirements of each child.

- Emphasising Continuity: Effective transitions often involve creating a sense of continuity and familiarity for children as they move from one setting to another. The pedagogy of listening ensures that the child’s voice is heard and respected throughout the transition process. This continuity can reduce anxiety and provide a sense of security during the transition.

- Reducing Anxiety and Resistance: By actively involving children and their families in the transition process, potential anxiety and resistance associated with change can be reduced. When children feel that their voices are heard and their concerns are addressed, they are more likely to approach transitions with a positive and open mindset.

- Building Positive Relationships: Effective transitions are often facilitated by strong relationships between educators, professionals, and families. The pedagogy of listening promotes open and respectful communication. It encourages them to listen to parents’ and children’s concerns, ideas, and expectations. This collaborative approach builds trust and fosters positive relationships, which are essential for successful transitions (Clark & Moss, 2005).

- Supporting Special Needs and Disabilities: For children with special educational needs or disabilities, understanding their unique perspectives and needs is even more critical during transitions. The Mosaic approach allows educators to create targeted and individualised plans for such children, ensuring that they receive the necessary support and accommodations as they move into new educational settings.

- Ensuring Smooth Information Flow: The pedagogy of listening encourages a culture of open communication and information sharing among all stakeholders. This is crucial during transitions because it ensures that relevant information about the child’s needs, preferences, and progress is effectively transferred between settings, preventing disruptions in the child’s education.

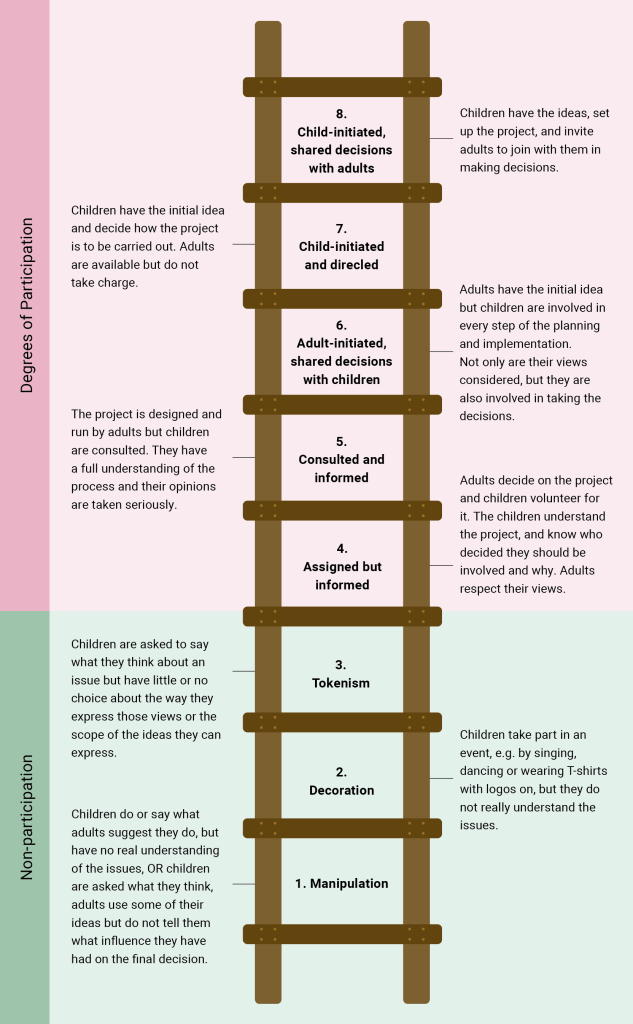

The term student voice that is used above can also be illustrated through Hart´s (1992) ladder of participation that illustrates the different ways in which children and young people can participate.

Figure 1: Ladder of Participation

This view and participation can be ensured verbally and non-verbally as it recognises that not all individuals may express themselves in conventional ways. Nevertheless, all needs are valid and must be attended to. Various methods, such as visual representations in Social Stories (Gray & Garand, 1993) or alternative and augmentative means of communication for transition plans, can be used to understand and incorporate individuals’ needs, desires, and aspirations during transitions. Moreover, to ensure the participation of both primary and secondary students in academic and social experiences, various participatory techniques are illustrated by Messiou (2012). These techniques can be effective in encouraging conversation with children.

The importance of acknowledging the student voice has been supported by practitioners, academics, and policy documents. Moreover, over the last decades it has gained attention due to the UN convention on the rights of Children (1989). The convention is the basis of the most complete statement of children’s rights ever produced and is the most widely ratified international human rights treaty in history. As it is highlighted in this convention, every child has rights “without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status” (Article 2). All this work reinforces the rights of children to be heard and taken into account through Articles 12 and 13, which is a fundamental part of a child’s transition journey.

Addressing transition challenges requires deploying strategies that consider the intersecting nature of various factors. Parental involvement also emerges as a key element in many interventions and should be integrated as an integral part of the process. Although international terminology may differ, the underlying principle remains the same: valuing the voices of individuals, embracing involvement, and promoting meaningful co-production, even for those who may be nonverbal (Egert et al., 2020). Involving families and being mindful of linguistic, social, cultural, and heritage factors is crucial in promoting inclusive practices that involve co-production.

Person-Centred Planning

For all young people the transition from childhood to adulthood involves consolidating identity, becoming more independent, establishing adult relationships, and living a fulfilled life which may include employment, further education, or any other aspiration that an individual may have. However, for young disabled people and their families, transition can often become more challenging, as a result of disability, than for others.

→ Person-Centred Planning is a process of “continual listening, and learning, focussed on the person.” Planning can support educational transition. For example, as a result of this process of removing barriers, focusing first on the dream and working back from a positive and possible future a Person-Centred Plan can help. Although there are different types of Person-Centred Planning a path is the most commonly used method when working with young people. A Person-Centred Planning path is a way of mapping out the actions required along the way. It is also very good for refocusing an existing team who perhaps support a young disabled person or a young person from another marginalised group who are encountering problems or feeling stuck, and mapping out a change in direction. With this in mind O’Brien (1998) describes the Person-Centred path process as one that “celebrates, relies on, and finds its sober hope in people’s interdependence” (O’Brien, 1998: 10). O’Brien continues by stating that “at its core, it is a vehicle for people to make worthwhile, and sometimes life changing, promises to one another” (O’Brien, 1998: 10).

It may be the case that an individual’s Person-Centred Planning journey highlights that they may not be able to achieve every part of their dream. However, even if this is the case, the Person-Centred Planning process explores ways in which the individual’s dream can be broken down to identify which aspects can be achieved.

An example which is often given in Person-Centred Planning training is if a young person had the aspiration of becoming an Airline Pilot. If this is not a realistic dream that can be achieved, then the Person-Centred Planning process can help to explore what it is about being a pilot that appeals to the young person. In exploring this further it might highlight that the person potentially associates the idea of being a pilot with wearing a uniform and helping people. Therefore, a positive outcome for the young person might not end up with them becoming a pilot but instead still working in the airport in a role that requires them to wear a uniform and to help people.

Person-Centred Planning also allows for questions to be asked in different ways, for example, “what is important to you and for you?” are often asked as the one question, when in reality they are two very different questions. Person-Centred Planning tools developed by Helen Sanderson can also be used to aid this process such as one-page profiles. These tools assist in gathering different perceptions of the individuals (Sanderson, 2023).

Self-determination in Person-Centred Planning

→ Self-determination in Person-Centred Planning regularly goes hand-in-hand as often when an individual begins the Person-Centred Planning journey it becomes apparent that they have lost their identity and with it their self-determination. This could be due to external factors such as, but not exclusive to, a negative experience in education or negative interactions with their peers (Legault, 2017)

The Self-Determination theory (SDT) is “a broad theory of human personality and motivation concerned with how the individual interacts with and depends on the social environment” (Legault, 2017: 1). It is thought of as a metatheory in the sense that it is made up of several “mini-theories” which fuse together to offer a comprehensive understanding of human motivation and functioning. SDT is based on the fundamental humanistic assumption that individuals naturally and actively orient themselves toward growth and self-organisation. In other words, people strive to expand and understand themselves by integrating new experiences; by cultivating their needs, desires, and interests; and by connecting with others and the outside world (Legault, 2017).

However, SDT also asserts that this natural growth tendency should not be assumed, and that people can become controlled, fragmented, and alienated if their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are undermined by a deficient social environment (Legault, 2017). Considering this theory, self-determination works on the basis of individuals being continuously involved in social interaction that gives them purpose and is part of them leading a fulfilled life.

Relating this notion back to Person-Centred Planning and educational transitions, it could be argued that one of the reasons Person-Centred Planning exists is because the reality is that individuals from marginalised groups are often not involved with continuous social interaction and being connected with others in the outside world. The reality is that for a lot of people who are regarded to be in marginalised groups of society, Person-Centred Planning aims to change that by removing the barriers that being marginalised often brings, enabling the person to dream big and as a result of doing so often this means that the individual slowly gains their self-determination back. By doing so Person-Centred Planning can help individuals aspire to be all they can be. This in turn should be apparent in their educational transition.

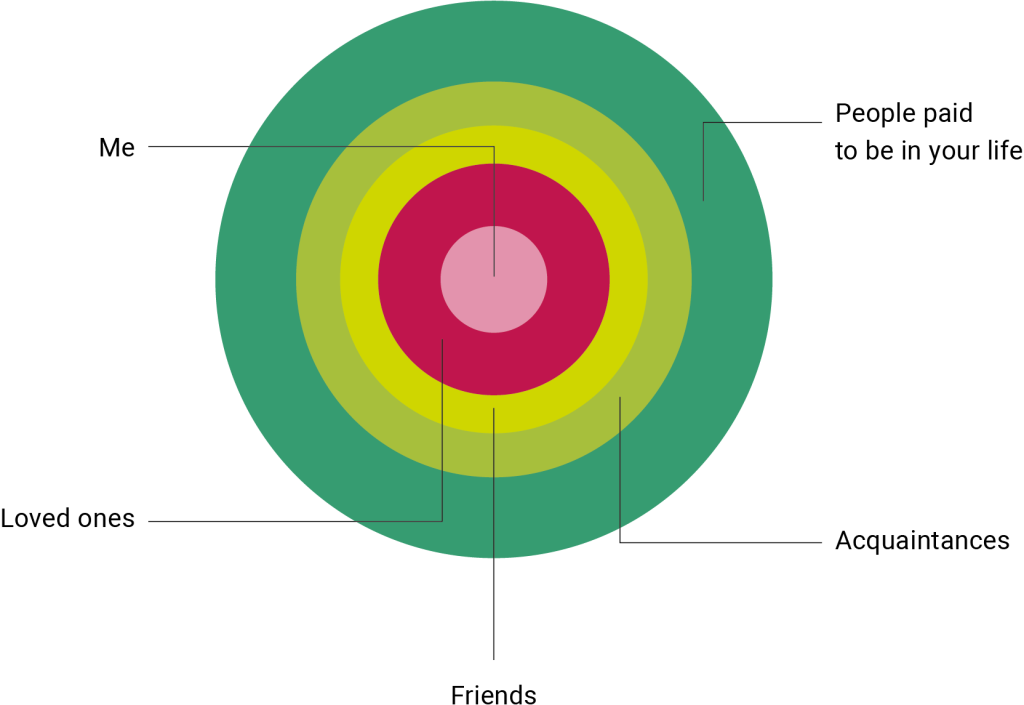

There are various tools that can be used prior and in the early stages of Person-Centred Planning. These various tools are aimed at enabling the individual at the heart of the plan and those closest to them to think differently about their dreams and aspirations, who they have around them, how they build on that, what needs to change and many other factors. One of the tools that is often used to support an individual in thinking about who they have around to support them is a Circle of Support (see Figure 1). This tool enables people to start making connections and perhaps realise what connections they already have but had perhaps overlooked. Connections are important for everyone regardless of ability. One viewpoint of this importance is “When we seek for connection, we restore the world to wholeness. Our seemingly separate lives become meaningful.”

- What does transition mean?

- What are the key aspects of successful transitions?

- How and why do educational transitions impact all aspects of our lives?

- Why are educational transitions important in order to address inclusion?

- Are there particular groups at risk of ineffective transitions?

- What are the barriers to successful educational transitions?

- How can school structures and practical activities tackle systemic inequalities?

- Are there theories that can explain the barriers to successful educational transitions?

- What might be some factors that would support teachers and educators in not being overwhelmed by this process?

- How does Person-Centred Planning, self-determination, and co-production relate to school transition?

- What are practical ways to support effective educational transitions?

“Transitions are generally linked to changes in a person’s appearance, activity, status, roles and relationships, as well as associated changes in the use of physical and social space, and/or changing contact with cultural beliefs, discourses and practices, especially where these are linked to changes of setting and in some cases dominant language. They often involve significant psychosocial and cultural adjustments with cognitive, social and emotional dimensions, depending on the nature and causes of the transition, the vulnerability or resilience of those affected and the degrees of change and continuity of experiences involved’’ (Vogler et al., 2008: 1).

Considering this definition as a starting point, it is acknowledged that transition processes have been studied in various disciplines, namely, anthropology, psychology, sociology, and education.

Nevertheless, in education, many authors have analysed educational transitions from different perspectives. Transition concepts are frequently used in specific ways, such as in terms of vertical and horizontal ‘passages’ (Kagan & Neuman, 1998). Vertical transitions refer to significant changes from one state or status to another and are frequently associated with ‘upward’ shifts such as from kindergarten to primary school, from primary to secondary and even, from one grade to another one. Horizontal transitions are less visible than vertical transitions and occur frequently. They refer to the everyday moves that children (or any person) make between different parts of their lives, such as going from home to school or from one care setting to another. These influence children’s movement across space and time, as well as their entry and exit from institutions that affect their well-being (Vogler et al., 2008).

There was a time when it was thought that the child had to be ready to make the transition. This meant they had to gain some knowledge and skills before moving to the next level of education. The characteristics of child readiness were introduced by Piaget’s theory of development (1936). Levels of cognitive development, maturity, and growth were used to determine what the child had learned. Later, research revealed that a kid’s abilities were greatly underestimated, as they were not measured in different ways. This weakened his hypothesis in several ways. However, numerous teachers and educators still employ his idea to acquire a greater understanding of their students’ cognition. This understanding of child readiness can be experienced as a barrier to ensuring successful transitions from an inclusive perspective, as each child and individual will have a unique developmental and learning process. Indeed, the context, which can be adjusted to better accommodate all children and situations, underscores the importance of discussing school and community readiness (Dockett & Perry, 2022).

Without change, there is no need for transition. This is why, during the transition processes, external and internal changes are experienced (Dockett & Perry, 2014). External refers to context-related changes. These may be new people, peers and teachers, new ways of interacting, the types of activities they are engaged in and new physical surroundings. Nevertheless, these contextual changes also bring internal changes that refer to new roles, responsibilities, and identities to the individual that is experiencing the transition. Major life events can cause us to reconsider who we are and where we fit in the world. In this regard, transitions may be seen as an opportunity for growth, to build new relationships, develop skills and not as something negative. However, appropriate and supportive contexts must be created to enable such opportunities. They can be interesting processes for personal growth, building new relationships and developing skills, but as it was mentioned before, it will be crucial to build appropriate context and provide support to ensure positive transition experiences, as negative ones, can have a negative impact on social, emotional, and academic spheres.

In this regard, the terms continuity and discontinuity are key concepts in relation to change and transition. Continuity has become a major focus for transition policy, with calls to promote continuity and reduce discontinuity, advocate for strategies that encourage children’s learning to continue, promoting lessons and experiences that build on what has come before (Dockett & Perry, 2022) and to avoid a dip in academic attainment (Jindal‐Snape & Cantali, 2019).

Even if transitions can be understood as an ongoing process throughout our lives this chapter will focus on the vertical transitions as we have considered that these are key in every individual academic career. The importance of the horizontal transitions in each of them, although not specified, is recognised, and will be addressed in more detail in a separate chapter.

Description of a structural disadvantage

In the education system, a risk of exclusion is directly related to the transition from one academic year to another, because educational transitions represent a critical phase for many learners, especially for those who receive specific support, such as those with Special Educational Needs (SEN). Through the lens of inclusion, transitions represent sensitive phases in the school career in which more vulnerable groups of students seem to experience a higher risk of marginalisation (Humphrey & Ainscow, 2006), losing opportunities for participation and learning they experience in the passage from one school grade to the next.

By understanding that it is the context that creates these systemic barriers for learning and participation it is crucial to recognise they can lead to these unsuccessful transitions within the educational sector. Such barriers stem from inequalities in educational opportunities, such as limited access to inclusive classrooms depending on locality, lack of individualised support through education plans, and appropriate accommodations. International and local laws in various countries often mandate the provision of these supports to ensure that individuals are included within their school environments and not just physically integrated (Lindsay, Wedell & Dockrell, 2020). These systemic factors significantly impact the smooth transition of individuals within educational settings, and it is important to address these factors understanding that every person has unique needs and approaches to learning. This necessitates a focus on equal opportunities and equity, prompting the need for changes and the development of provisions that enable individuals to access their entitlements.

For instance, a lack of appropriate curriculum and reasonable adjustments in primary schools can make the transition to secondary school challenging (Equality Act, 2010; 2014). Failure to identify and address individuals’ needs, such as communication difficulties, early on can result in an unfulfilling educational experience and subsequent identification of emotional and behavioural difficulties during the transition to secondary education (Evangelou et al., 2003; Mandy et al., 2016). Limited support networks and lack of relationships with educators, families, other professionals and facilitators further compound these challenges (Coffey, 2013; McLeod, 2023). Thus, the establishment of multidisciplinary networks and support systems is essential in facilitating successful transitions. Teachers and educators cannot be expected to navigate these moments alone, as it is a systemic issue that requires sustainable practices to support both learners and stakeholders. In some contexts, access to expert input and use of technology is vital to ensure the creation of an inclusive learning experience. This involves enabling teachers and educators to implement augmentative support software, screen readers, and communication devices, promoting accessibility for children with diverse needs (Hersh, 2020). Additionally, equal distribution of services within geographical spaces and readiness of families to enter the educational system, including those from rural areas, must be taken into consideration. On the other hand, in some cases, the choice for the appropriate school placement is not always available. For example, some research data revealed that the way certain school systems operate undermine a variety of possibilities for young learners. For instance, the transition from lower to upper secondary school in Italy is connected with the first differentiation in different types of schools, some of them with a more academic-orientation and others with a more vocational orientation. The choice of the type of school at that stage can be a decisive moment in which more vulnerable groups experience marginalisation, in the sense that they enrol to a school which leads to underachievement or that reduces their expectation early on in their school career (Barban & White, 2011; Romito, 2014).

Discrimination, bias, and a lack of inclusive culture and understanding of diversity contribute to exclusionary practices and limit resource allocation. Unconscious biases, combined with limited resources, can lead to discriminatory practices that exclude individuals from meaningful educational experiences and transitions (Council for Disabled Children, 2015). It is important to challenge assumptions about learners’ needs, the purpose of schooling and prior experiences to foster inclusivity. These considerations extend beyond early years (Connolly & Gersch, 2016; Fontil et al., 2020) and primary education and apply to transitions from secondary education to higher education as mentioned above. Unconscious biases and inequalities related to financial status or opportunities continue to impact how decisions are made and how students’ work is assessed, as well as decisions about their future.

For example, difficulties in transition can occur due to different backgrounds. An Italian study about immigrant children’s transition to upper secondary school has shown that the final evaluations attributed by teachers to students at the end of lower secondary school were predictors of secondary school choice: the enrolment in gymnasium rather than in technical or vocational institute depended on the previous outcome (parental education level of education influenced the choice of school not of previous achievements). Immigrants had a significantly lower probability of enrolling in technical institutes and gymnasium compared with natives and second-generation students. Two possible explanations could be that 1) immigrants and their families had different ideas in terms of investing in education and 2) the choice of a type of upper secondary school was affected by poor and potentially biased counselling received by teachers during the last year of lower secondary school, who suggested the enrolment in a vocational or technical institute even if they had the same results as natives (Barban & White, 2011). Furthermore, another study conducted in two lower secondary schools in Milan has shown that teachers tend to suggest to the family with a low socio-cultural status a lower level for upper secondary school, justifying their reflections with the social background and students’ life conditions. In the frequent cases where students’ outcomes were not clearly located on one level, but between two levels, teachers’ discussions focused on the cultural and economic resources of the families and not about peoples’ skills (Romito, 2014). Some statistical data from Italian educational institutions clearly showed that pupils with lower results at lower secondary schools and disabled learners were over-represented in some types of job-oriented schools. For instance, data about disabled students showed a preference towards vocational institutes (6.9%) than technical institutes (2.3%) and gymnasium (1.4%). This means that the majority of them attend a vocational institute (47.2%), instead of a technical institute (32.7%) or a gymnasium (24.9%), even if at the end of the lower secondary school they can choose whatever type of upper secondary school (MI, 2020).

Campus readiness, including physical, emotional, and social accessibility, is crucial for individuals with intersectional needs who require accommodations and support to navigate the system. Higher education has a noticeable lack of representation for disabled students in this setting who tend to experience less favourable outcomes compared to their non-disabled peers. Disabled students are more prone to discontinuing their courses, and those who do complete their degrees often achieve lower academic results. For instance, in the 2016/17 academic year, a smaller percentage of disabled learners in the UK received a first or upper second-class degree compared to those without reported disabilities (Office for National Statistics: 2019). These disparities go beyond disability and to a wider area of potentially marginalised groups; for example, the disparity in degree attainment between White UK-domiciled students and UK-domiciled ethnic minority (students at the first-degree level is commonly referred to as the ‘ethnicity awarding gap.’ This gap represents the difference in the percentage of White students receiving first or upper second-class degrees and the percentage of ethnic minority learners achieving degrees of the same calibre (UUK & NUS, 2019). Representation in learning experiences and curricula is vital for students to feel a sense of belonging and experience smoother transitions.

Employment transitions also pose challenges, as prospective employers may harbour negative judgments towards individuals who belong to marginalised groups (Bonaccio et al., 2022). Cultural and linguistic barriers further compound these challenges, particularly in diverse and turbulent times. These barriers can include ethnocentrism, stereotyping, psychological, language, geographical distance, and conflicting values. Bilingual learners’ performance is influenced by their prior knowledge, and culturally sensitive questions should align with their familiarity with the subject matter. Culturally sensitive interaction and management strategies are crucial as cross-cultural transitions pose challenges, requiring individuals to learn new skills, resolve cultural tensions, and manage stress (Ward & Szabó, 2019). Children and their families from diverse backgrounds may face additional stressors, including normative and non-normative educational transitions, discrimination, financial vulnerability, and practical problems (Bradley, 2000; Hanassab, 2006; Lee & Rice, 2007; Li & Kaye, 1998; Lun et al., 2010; McGhie, 2017; Sawir et al., 2008; Sawir et al., 2012).

Considering these factors is essential throughout the educational journey, from early years to university and beyond.

We also need to think about when the transition journey should start. In Scotland there is often a debate around what age transition should be expected to begin, especially from secondary school.

Theoretical Frameworks and PPCT model (process, person, context, time)

Given the various systemic inequalities operating during transitions, teachers and educators may easily feel overwhelmed and think they have no control over external factors. These factors include government policies on inclusion or the treatment of underserved communities and populations at risk of marginalisation such as migrants, learners with diverse learning styles to give some examples. This could lead to disengagement and a belief that they cannot make a difference. Theoretical perspectives can help teachers and educators navigate this complexity, make sense of the factors involved, and maintain a sense of coherence. The process of educational transitions involves multiple theories and factors due to its complex nature.

In psychology, the ecological system (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) has been useful in understanding transitions and their significance for children. Children’s development and learning are viewed in relation to factors and circumstances covering the micro to the macro level in this model. This theory defines a transition as changes in activities, relationships, identities, and roles (Ballam et al., 2017). Bronfenbrenner stated that “an ecological transition occurs whenever a person’s position in the ecological environment is altered as a result of a change in role, setting, or both” (1979: 26). This definition can be applied to educational transition as meaning that it describes the change experienced by individuals in the moment they enter or leave school or pass from one school grade into the next. It affects the learners’ position in their ecological environment in the sense that by crossing social, academic, and procedural issues (Hargreaves, 1990) transition influences their psychological, social and intellectual wellbeing. In some cases, such transitions represent new possibilities, a time to grow academically, socially, and emotionally (Roeser, Eccles & Freedman-Doan, 1999). At the same time, the transition might be characterised by discontinuity in physical location, difficulties in relationships with teachers and alienation from peer groups (Ashton, 2008).

Whereas in sociology, one of the key concepts relating to transitions is considered Bourdieu’s “social capital”. The goal is to uncover the most deeply buried structures of different social worlds, as well as the mechanisms that tend to ensure either their reproduction or transformation over time (Bourdieu, 1973). Related to a bio-ecological framework, his work is particularly interesting in clarifying how events in the macro-system (societal and cultural norms that shape the development) and chrono-system (the role of the time affecting people’s growth and change, including life and historical events) may impact individuals (O’Toole, 2014). This means that for example, some parents will have greater or less access to resources, opportunities, knowledge, and skills inside and outside their family to provide needed experiences to their children.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979) is a prominent one emphasising on the influence of various systems and stages on individuals during transitions. This is in line with the previous realisation that barriers or indeed facilitators to inclusive transitions which are systemic and intersectional (Fontil et al., 2020). Social constructivist theory highlights the importance of understanding learners within their sociocultural context (Bourdieu, 1973), emphasising the role of cultural responsiveness in creating successful transitions (Vogler et al., 2008). Limited social interactions and collaboration opportunities can hinder learners’ understanding and adjustment during transitions. Creating a supportive and collaborative classroom environment that encourages peer interactions and scaffolding (Morcom, 2016) can help mitigate this barrier.

When considering educational transitions, it is essential to acknowledge other diverse theories at play. For instance, trauma response theory could also be considered, especially when learners have experienced difficult or traumatic situations that impact their journey (Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities, 2023). Taking these factors into account allows teachers and educators to create appropriate accommodations that support students effectively. Implementing trauma-informed practices, such as creating safe and predictable environments and establishing trusting relationships, can support their adjustment and well-being during transitions.

Notwithstanding the above, in this chapter we are drawing heavily on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory with cultural responsiveness theory. By understanding the multiple systems that shape a person’s development, such as the microsystem (including individual needs and family), the mesosystem (interactions between different environments), the exosystem (indirect influences through discourses and language), and the macrosystem (cultural and societal influences), we can provide a comprehensive approach to educational transitions.

Cultural and social factors, including limited representation of students’ cultural identities, can affect their sense of belonging and engagement. Culturally responsive teaching practices can address these factors and facilitate successful transitions.

By incorporating a sociocultural perspective and cultural responsiveness, we ensure that peoples’ cultural backgrounds, experiences, and identities are valued and integrated into the transition process (Lam, 2014). Recognising the impact of various interventions and connecting the different systems through relational pedagogy fosters a supportive and inclusive environment for individuals during transitions and throughout their educational journey.

Some practical strategies and insights to navigate the complexities of educational transitions will be provided below to equip teachers and educators to better support learners in their transition experiences, fostering their holistic development and creating a positive and inclusive educational environment.

Particularly in the context of Bronfenbrenner’s work, his framework on process, person, context, and time in facilitating positive transitions, is mostly found in his later work (Hayes, O’Toole & Halpenny, 2023). The most crucial aspect emphasised by Bronfenbrenner is the process, particularly the relationships involved. Strong relationships between stakeholders, students, and families are vital for successful transitions. The care, empathy, and understanding shown by adults towards children significantly impact their development. While various strategies and approaches exist, it is essential to remember that relationships underpin them all. Kindness and genuine concern for the well-being of learners creates a positive environment for successful transitions. Then, the person element recognises how factors like culture, disability, and socioeconomics can affect the transition experience (Aikens and Barbarin, 2008). For example, an autistic child starting in a new environment may find it particularly challenging (Stoner et al., 2007). Language differences between home and school can also complicate transitions. However, what is significant about Bronfenbrenner’s work is that he does not solely attribute responsibility for support to the individual; it also lies within the context.

Considering the context is crucial. Building links between different systems, such as ensuring consistent support for an autistic child or embracing the linguistic and cultural diversity of students, can facilitate smoother transitions. It is important to create an environment where individuals feel visible and represented, with resources and materials that reflect their identities and experiences. According to a key worker approach the same person should be meeting them at the door. Is this happening? Or in a primary setting, are linkages formed for the child who comes into an educational session with a different language than the one that is spoken and knows what to expect? Is this seen in a deficit way, that she does not speak English, for example, or is it seen in a far more culturally attuned way? Maybe the child does not speak English, but they do speak Russian and Romanian and other languages. Does the child see themselves when they come to the educational setting if they are visible? Are there dolls who look like them in the early childhood setting? Are there books in the primary setting or the secondary setting that talk about people who are like me and my family? Arguably, context is hugely important. Do we create linkages for people in their transition? Or do our structures erect disjuncture and difficulties for people to make those transitions?

Time is another factor to consider, and that can be your personal time, or it can be the more social historical piece. Personal time, such as a pupil’s developmental stage, can influence the ease of transition. Younger children, for example, may find it harder to transition to primary school. Social-historical factors, such as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education, also play a role. Recognising the timing and adapting accordingly can help mitigate difficulties.

Continuity in relationships and strategies is important across educational stages, from early years to primary, secondary, and higher education. Using data-informed materials and providing early tutor support can be beneficial, especially for marginalised groups. Establishing and nurturing relationships can help address oppression and cater to individual needs, as advocated by Paulo Freire (1993).

Lastly, recognising that children do not exist in isolation but within families, communities, and cultures is crucial. Educational settings need to value and prioritise these wider relationships. Inclusive strategies for building connections with families should focus on fostering positive encounters rather than relying on specific methods or tools, it is important to someone now, and for the future. “It is not simply a collection of new techniques for planning to replace individual Programme Planning” (van Dam et al., 2008: 3). It is based on a completely different way of seeing and working. The journey of Person-Centred Planning is fundamentally about sharing power and community inclusion.

Key transition moments

As mentioned above, in this chapter we will focus on the following vertical transitions: from home to early childhood education; from early childhood education to primary education; from primary education to secondary education: from secondary education to further and higher education; from secondary school and university to the employment sector; and from mainstream school to special settings and vice versa.

➔ From home to early childhood education

This is a key transition because it is the separation of the children from their families. According to Bowlby’s attachment theory (1969), which is supported by Peter Elfer’s key person approach, cooperation between families and carers or educators is required to ensure secure contexts and facilitate settling (Elfer et al., 2012). Attachment theory supports the value of strong attachment/bond with a primary caregiver and later with the educators who care for them; this is critical to a child’s transition and the need to feel secure in order to explore, learn and engage with their surroundings. Ensuring the individual needs of each child are responded to and that the child is supported in establishing a positive relationship with themselves should be prioritised. When children form a strong bond with educators, they are much more likely to feel safe, confident, included, and happy. Many scholars agree that adaptation is a process with a variable duration. It concludes when a child effectively copes with the separation from their primary attachment figures, which may include their mother, father, or grandparents. During this process, the child also takes on their new role as an early childhood student and becomes accustomed to their new physical, emotional, educational, and school environments (Fernández, 2016).

➔ From early childhood education to primary school

This change comes at a crucial juncture as it may contribute to future transitions and the child’s socio-emotional development. It is a moment in which the discontinuity process is experienced because of various circumstances of personal, social, and academic growth. Children and their families experience feelings of loss of familiarity, concern, nervousness, or uncertainty related to new requirements as a primary student and their new role, not only for children but also for parents. However, it also represents personal, social, and academic stimulation (Niesel & Griebel, 2007). This is related to the differences between the two stages and the volume of changes that are faced in terms of discontinuities in new reference teachers, unfamiliar spaces, different time distribution and new teaching-learning approaches. A positive experience at this stage may affect their ability to reach their full potential and deal with future transitions (OECD, 2017a). In primary education, the learning process begins to be considered as a formal activity. There is evidence that a positive start to school is important for later social and educational outcomes (Davies & Troy, 2020). Children who start positively, may be better prepared to take advantage of the educational opportunities that come their way and develop successful friendships and social networks. In contrast, children who experience academic and social difficulties at the beginning of school are likely to continue to struggle throughout their school careers, and frequently into adulthood (Demirtaş-Zorbaz & Ergene, 2019).

➔ From primary to secondary education

According to research, for many pupils, the transition from primary to secondary education is an overwhelming process that requires adequate support (Bloyce & Frederickson, 2012). Adolescents, because of puberty, go through a variety of physical and emotional changes and challenges during this stage. Making the transition for many pupils involves not only adjusting to a new and larger physical environment, but also adapting to different school expectations, new ways of thinking, different teachers, learning in a variety of subject areas, and interacting with a larger number of peers. The ability of a learner to cope with these changes has a significant impact on how they feel about school and progress through secondary education (Hopwood et al., 2016). This can bring the emergence of anxiety processes affecting their self-esteem and academic motivation (Jindal-Snape et al., 2023).

➔ From secondary education to further and higher education

All educational transitions are important because they are times of change and potential uncertainty but the transition to post-compulsory education has an added risk and value because it is the first time when learners may decide not to continue their studies. When it comes to promoting equity in education systems and equal opportunities for all students, educational transitions from compulsory to post-compulsory education are crucial points and key components (Egido & Martínez-Novillo, 2020). Moreover, they can present a challenging time for young people with emerging expectations and conflict in terms of perceived independence both at home and in education. This is also a period of exploration when young individuals are shaping their identities, developing personal values, and contemplating future aspirations, often requiring support and guidance (Morris & Atkinson, 2018).

Educational pathways have changed and become more diverse and plural because of recent social changes such as school year extension, lifestyle diversification, and increased labour market flexibility. This “de-standardisation” does not, however, imply that institutional patterns and cultural values do not shape what is perceived as normal in each context and influence students’ decisions. In terms of the construction and perpetuation of inequalities, this stage may mark the setting out of various paths based on different social values, resulting in a variety of life experiences and opportunities (Tarabini & Ingram, 2018).

Most education systems continue to differentiate between an academic stream that prepares people for university admission and a vocational route designated for students’ training for the labour market once compulsory schooling is completed. Research has shown that this institutional divergence is associated with a class bias since family socioeconomic background may determine the course selected after completing compulsory schooling (Santos, 2023).

Transitioning to university education is seen as a significant challenge for them, involving changes in environment, instructors, and systems. This shift is both anticipated and feared. For learners, moving from having familiar academic accommodations to the uncertainty of their use in university can be daunting. Lack of knowledge about the new educational system and its resources adds to concerns. The absence of transition measures can lead to difficulties and even dropouts for disabled students. Proper guidance during this stage is crucial, acting as a bridge between secondary and university education. It helps people develop adaptability skills, ensuring a successful integration into university studies and preventing potential failures and dropouts (CERMI, 2020).

➔ From secondary school and university to the employment sector

Transitioning from school to work can be challenging and result in unemployment. Early school dropouts are considered to have an impact on lower skills and educational attainment, making them more difficult to employ than their peers who stayed in school longer. In OECD countries, most people leave school between the ages of 20 and 24, but 13% of 15 to 19-year-olds have already dropped out. To ensure successful entry into the labour market, individuals must complete at least upper secondary education. Staying in school not only improves educational attainment but also develops skills necessary for a smoother transition into the workforce. As a result, identifying and supporting students who are at risk of dropping out will be necessary (OECD, 2017b).