Section 4: Fostering Student Well-Being and Emotional Health

Breaking the Silence – Empowering Schools in the Practice of Trauma Informed Education

Julia Bialek; Evrim Çetinkaya Yıldız; Cynthy K. Haihambo; and Ramona Thümmler

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“We would like to start with a case study from the school that illustrates the difference between trauma-sensitive interventions and standard intervention practice.

It is about a 6 year old boy who attended the 1st grade. He had many conflicts with his teachers because he kept climbing on tables and trampling over everything that was on them, such as notebooks, books, etc. The teachers tried to stop this behaviour with different interventions, the boy was even suspended from school several times for some days, but the interventions did not show any effects.

During the observation of this boy, it became clear that this behaviour was triggered by different situations. The main triggers were moments when he did not know exactly what was going to happen next.

After traumatic experiences, anything that cannot be fully predicted and influenced feels dangerous and threatening to the person affected. His body reacted to these situations with massive stress, which forced the boy to remove the danger. He found a very effective strategy: by climbing on the tables he took control of the situation that he experienced as dangerous. Wat would happen next became predictable and controllable for him, and he could feel safe again.

Once we understood this, we worked with him to find alternative ways of dealing with situations where he felt threatened. He was asked what he needed when he felt uncomfortable in class and he said that he needed a place to hide in class. He was allowed to build a small safe place in a corner of the class. Great care was also taken to ensure that the structure of the class was very transparent and predictable for him. And additional procedures were agreed with him for difficult situations by agreeing on emergency signals he could use to indicate the need for support.

With this support, the boy was able to participate in the class in a relatively stable way without having to control it through his behaviour. This was possible because he had been given alternative ways of acting which gave him a sense of security, predictability and control. The previous “if…. then” interventions had only taken away his ability to feel safe without offering him an alternative. With these interventions the boy could not change his behaviour.”

Initial questions

- What is trauma? What are the effects of trauma on children, on the classroom, and on the school climate? How to break the silence about these questions?

- What are the responsibilities of educational staff and education institutions when working with children who have had traumatic experiences?

- What are the options to support learners who have had traumatic experiences?

- What are the responsibilities of school for trauma awareness and trauma prevention?

- How does society take responsibility for empowering individuals, peers and teachers?

- How can silence be broken?

Introduction to Topic

The number of children and young people in the world who are exposed to traumatic events on a daily basis due to neglect and abuse, violence against them, deprivation of basic needs, exclusion and discrimination is increasing (Mew, Koenen, & Lowe, 2022; UNHCR, 2023). In addition to these micro- and meso systemic factors, many children around the world are exposed to man-made macro- and ecosystemic factors, such as wars, natural disasters including floods, severe droughts and earthquakes, and structural inequalities, leading to migration and multiple factors of vulnerability. It is therefore necessary for teachers to have trauma-sensitive knowledge and to use this knowledge to develop trauma-informed interventions (Carello & Butler 2014).

Trauma is defined as the events experienced or witnessed by the individual when death, threat of death, serious injury, or a threat to the integrity of the body occurs in human life (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013, pp. 265, 266). Children and adolescents around the world experience high rates of traumatic experiences. These include physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; neglect; exposure to community violence; bullying; natural disasters; poverty; homelessness; immigration; and parental problems such as domestic violence, incarceration, death, mental illness, involvement in substance abuse, and military deployment. Traumatic experiences undermine students’ ability to learn, to form relationships, and to regulate their emotions and behaviour, putting them at increased risk for trauma and a range of negative academic, social, emotional, and vocational outcomes (Schäfer, Gast, Hofmann, et. al, 2019; Vibhakar, Allen, Gee & Meister-Stedmann, 2019). For many children and young people, the school environment is the best option for accessing support services, particularly during periods of trauma that are inevitable in their developmental stages. The school, as a place of inclusion, education and socialisation, has a responsibility to positively identify and respond to the needs of learners who have experienced trauma in their lives. WithIn trauma-informed schools or places of education, all adults who come into contact with children, including teachers, school counsellors, school administrators and parents, should be informed about the effects of trauma on the nervous system and the psychosocial impact of trauma on children. Teachers and other role players in the school should therefore be empowered to practice embedded trauma-informed education.

In this chapter we explain the meaning of trauma-informed education, the types of trauma and possible school responses. We focus on the professionalisation of teachers for trauma-informed education and on the well-being of teachers in this work.

Key aspects

What is trauma?

The term ‘trauma’ is derived from the Greek word ‘trauma’, which translates literally as ‘wound’ or ‘injury’. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines trauma as “a delayed or protracted response to a stressful event or situation (either short or long-lasting) of an exceptionally threatening or long-lasting nature, which is likely to cause pervasive distress in almost anyone” (WHO, 2010). Several key characteristics of trauma can be identified.

- Such an event can be overwhelming. The individual lacks the capacity to cope with the circumstances and experiences a sense of vulnerability and exposure. The potential for resolution is severely constrained or absent. The extent to which an individual is affected by a traumatic event is dependent on their personal circumstances and the potential for coping mechanisms to be exercised.

- Such occurrences are typically unanticipated. It is not possible to predict the occurrence of such an event, nor can one assume that another individual will perpetuate such an act against them.

- It engenders feelings of fear and helplessness. The occurrence is so pervasive that it causes significant anxiety and feelings of helplessness.

- It is life-threatening. The occurrence is so devastating that it alters subsequent lives and is remembered for an extended period.

The definition of a traumatic event is contingent upon the individual’s experience and perception of the event, rather than the specifics of the event itself. The person’s available options are of paramount importance for assessing and coping with the trauma.Childhood trauma can be defined as an event experienced by a child that evokes fear and is commonly violent, dangerous, or life-threatening. The experience of physical or emotional neglect or abuse can have a traumatic effect on children. Similarly, one-off occurrences such as road traffic accidents, natural disasters (e.g. hurricanes), the death of a loved one or a significant medical event can also have a profound psychological impact on children. The global pandemic of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and the associated public health measures, including prolonged school closures, were experienced as traumatic by many children, particularly those whose educational institutions remained inaccessible for extended periods.

It is a common misconception that childhood trauma is exclusively characterised by direct experiences of the child in question. Observing a loved one undergoing a significant health challenge can be profoundly distressing for children for example. It is erroneous to assume that all intense experiences are traumatic. Trauma is not a final, life-determining fate. It can be dealt with and healed. Furthermore, in light of the growing multicultural and diverse nature of schools, it is imperative for educators to recognise that certain experiences may be perceived as traumatic by children from one cultural background, while being less so by those from another. It is therefore incumbent upon teachers to ascertain from their pupils’ behaviours and responses (which may be observed, reflected upon, undertaken, illustrated or conveyed in narrative form) whether or not they have been traumatised by a specific event in their lives. Cultural identity is not the only determining factor in the experience of trauma. A number of factors contribute to an individual’s vulnerability, including membership of a disadvantaged group. Such groups may include people with a migration background, persons with disabilities and special needs, those living below the income threshold, and those enduring bullying, stigmatisation and exclusion. Such circumstances can render individuals more vulnerable to traumatic experiences, and to a greater extent than might otherwise be the case. One illustrative example is that of natural disasters such as floods. In the event of such occurrences, those who are impoverished and reside in regions with inadequate infrastructure are the most severely affected. They are at an elevated risk of losing their lives and possessions, and may require a longer period to rebuild their lives. In addition to their vulnerabilities, they also do not have back-up resources like insurance or savings to rebuild their lives.

Similar circumstances have been documented in cases where individuals have been exposed to armed conflict, torture, and forced displacement. In 2022 over 108 million people worldwide were forced to flee their homes due to a range of factors, including war, torture, natural disasters, and political persecution. These individuals often lose not only their homeland but also their loved ones and social support systems (UNHCR, 2023). Furthermore, they frequently encounter additional trauma in their new surroundings due to stigma, discrimination, and rejection. Trauma-informed education equips educators with the knowledge and skills to provide sensitive and supportive learning environments for children with migration histories, thereby reducing the risk of secondary trauma.

What are the types of trauma?

In the literature, there are several different classifications of trauma. Some classify it according to the number and duration of the traumatic event. Others classify it according to the source of trauma.

Different types of trauma can be distinguished according to the type and length of exposure. Single-event trauma, sometimes referred to as Type I trauma, describes abrupt, unplanned events that pose a serious risk. Serious accidents, natural disasters, and violent attacks are a few examples. These traumas usually have a distinct beginning and might result in disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder (ASD) (Terr, 1991). On the other hand, Type II trauma is the result of persistent or recurrent exposure to stressful events. This category, which encompasses ongoing events like persistent emotional or physical abuse, marital violence, or extended exposure to conflict, is frequently predicted. Complex psychological effects, such as challenges with emotional regulation and interpersonal interactions, might result from the cumulative impact of Type II trauma (Courtois & Ford, 2016).

Apart from Type I and Type II trauma, the differentiation between “Big T” and “Small T” traumas is also a helpful classification. “Big T” traumas are those intense or overpowering incidents that are usually connected to severe and unmistakably traumatic situations, such as rape, serious accidents, child abuse, and war. Because of their severity and lasting effects, these incidents are typically acknowledged as major traumatic experiences (van der Kolk, 2015). Even though they have the capacity to be extremely overwhelming, “Small T” traumas are frequently more subdued and may not be identified as such right away. A few instances are losing a job, moving to a new house, or losing a loved one or pet. “Small T” traumas may not seem as dramatic, but if they are not properly addressed, they can have a major and long-lasting effect on a person’s mental health.

Acute, chronic, and complicated trauma are other categories of trauma (DeThierry, 2015). A single incident causes acute trauma. It is a psychological trauma brought on by an extremely stressful incident, including going through a violent or natural disaster, seeing a major car accident, or being in a car accident. Trauma of this kind might result in acute stress disorder (ASD), a mental illness that usually manifests three days after the incident and can last for up to a month (American Psychological Association, 2020). Long-term mental health problems might arise from acute trauma if it is not appropriately treated (Herman, 2015). The result of recurrent and extended stressful encounters is chronic trauma. It may be the consequence of chronic conditions such as poverty, marital violence, or abuse on a physical, sexual, or emotional level. More severe psychological consequences, like anxiety, sadness, and complicated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), are frequently brought on by this kind of trauma (van der Kolk, 20015). When a person experiences several ongoing or protracted traumatic events—often starting in childhood—they develop complex trauma. This can result from events such as childhood abuse or neglect, domestic violence, sexual assault, or war-related trauma and is tightly linked to generational trauma (Courtois & Ford, 2016). Emotional control, self-perception, and the capacity to establish and sustain healthy relationships can all be significantly impacted by complex trauma. Complex trauma’s long-term impacts can cause serious problems with one’s physical and mental health (DeThierry, 2015).

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN, 2023) categorises trauma based on the occurrence that led to it. Trauma occurs when a youngster experiences or sees an event that makes them feel extremely threatened. Children and teenagers may be exposed to a variety of traumatic events or trauma types. Children may be subjected to a variety of traumas, including bullying, complex trauma, disasters, intimate partner violence, early childhood trauma, medical trauma, physical abuse, trauma from refugees, sexual abuse, sex trafficking, terrorism and violence, and traumatic grief.

Putting traumatic occurrences into categories such as those generated by nature and those purposefully brought on by human hands is another popular way to group traumatising experiences. Yet inadvertent, human-caused accidents can also occasionally have traumatic effects. Human carelessness frequently results in the transformation of natural occurrences into traumatic ones. An earthquake, for instance, is a natural occurrence, but it causes destruction because structures built in an unsafe location get damaged. Experiences that could be considered natural disasters that do not cause damage or casualties could turn into painful experiences if earthquake-resistant structures are developed. Lastly, it should be mentioned that traumatic incidents can occur in large or small groups. A single person or a small group of people may be impacted by an event, but in other situations, like forced migration and war, it may have a mass effect on a significant number of people. Comprehending distinct forms of trauma is essential to customising efficient interventions and therapies that cater to the individual requirements of individuals impacted (Courtois & Ford, 2016).

The prevalence of trauma: A few global and national statistics from our countries

Worldwide statistics: Regretfully, across the globe, children are exposed to various forms of trauma at a very high rate. This is amply supported by the findings of extensive research projects on the topic. According to projections from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), 1 billion children between the ages of 2 and 17 may have been victims of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse or neglect in the previous year. Approximately 420 million children are estimated to be living in conflict zones by UNICEF (2019). There is a greater chance of trauma from violence, displacement, and war for children in these locations. More than 35 million children have been forcefully relocated due to conflict according to the UNHCR (UN Refugee Agency), which greatly contributes to trauma experiences. Sexual abuse before the age of eighteen is estimated by the World Health Organization (2018) to affect about 18% of girls and 8% of boys worldwide. Over 100 million children are impacted by natural disasters and humanitarian crises annually according to UNICEF (2020), which causes severe psychological damage. Felitti et al.’s (1998) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study investigated the long-term effects of maltreatment, neglect, and dysfunctional households on the health and behaviour of adults. According to the study, more than two thirds of the individuals said they had had at least one ACE, and over 12.5% said they had had four or more.

Turkey: The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Social Services and Child Protection Agency released a study on domestic violence and child abuse in Türkiye in 2010. The study’s findings show that 51% of Turkish children aged 7 to 18 experienced both physical and emotional abuse, 43% experienced physical neglect, 25% experienced emotional neglect, and 3% experienced sexual abuse. As per UNICEF (2010, p 17-37) the survey found that 56% of children had witnessed physical abuse, 49% had witnessed mental abuse, and 10% had witnessed sexual abuse.

Şirin & Rogers-Şirin (2015) did research with 311 children (mean age 12) at a refugee camp in Türkiye in 2012. They conducted a study on the traumatic experiences and psychological problems of children that are under temporary protection status in Turkey. Results revealed that compared to their Turkish peers, they are in a higher risk group for survival. These children had experienced very high levels of trauma:

- 79% of children witnessed the deaths of family members

- 60% of children witnessed physical injury or shooting of a family member

- 30% of children were exposed to violence (injury, shooting)

- almost half of the children had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), ten times more often than other children

- 44% of the children showed symptoms of depression

- almost a quarter of these children experiences daily psychosomatic pains in their arms and legs

- about one in five children experiences headaches on a daily basis

In February 2023, Unicef reported that 4.6 million Turkish children and 2.5 million Syrian children were affected by the earthquake in Turkey and Syria. One year after the earthquake, according to the data announced by Unicef (2024), psychological support was provided to 1.5 million children and caregivers in Turkey.

Germany: In Germany in over the the last number of years, several discussions about child abuse, neglect and emotional and physical maltreatment of children and also of sexual abuse were held.

Research on respondents from the general population (n = 2504) aged 14 and over shows the presence of severe emotional maltreatment in 1.6% of respondents, severe physical maltreatment was reported by 2.8% of respondents and severe sexual maltreatment by 1.9%. Severe emotional neglect was reported by 6.6% of respondents and severe physical neglect by 10.8%. In the most recent study on the prevalence of sexual violence in Germany, a representative sample of 2513 persons over 14 years of age was interviewed. It showed that 0.6% of the male respondents and 1.2% of the female respondents reported having been victims of sexualised violence within the last 12 months (Witt, Glaesmer, Jud et al., 2018).

Namibia: In a study about post-traumatic stress disorder amongst children aged 8–18 affected by the 2011 northern-Namibia floods (Taukeni S. G., Chitiyo,G., Chitiyo, M. Asino, and G. Shipena, G.) the results show that 55.2% of learners aged 12 and below and 72.8% of learners aged 13 and above reported experiencing symptoms of trauma following the floods in Northern Namibia, 2 years after the event.

Descendants of the genocide that was committed by the German Truppe in Namibia against the Herero and Nama people of Namibia in 1904 -1908 have revealed signs of transgenerational trauma.

Many children and adults continue to battle the persisting trauma caused by the COVID 19 pandemic between 2020 – 2023 (deaths of loved ones, isolation from friends, falling behind with education targets, online learning) (UNESCO, 2022).

In a study on children’s use of online platforms and vulnerabilities in the online space in Namibia, 81% of children aged 12–17 were found to be internet users during the time of the research. In the past year alone, 9% of internet users aged 12–17 in Namibia were subjected to clear examples of online sexual exploitation and abuse that included blackmailing children to engage in sexual activities, sharing their sexual images without permission, or coercing them to engage in sexual activities through promises of money or gifts (ECPAT, INTERPOL, and UNICEF (2022). There are continuous cases reported of childhood trauma emanating from abuse in the online space.

A child abuse survey conducted in Namibia revealed that nearly two out of five females (39.6%) and males (45.0%) aged 18-24 years experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence in childhood (Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Child Welfare, Republic of Namibia, 2020).

Possible Effects of Trauma

Exposure to different types of traumatic events may have different consequences. Not everyone who experiences a traumatic event develops post-traumatic stress disorder, as the experience of a potentially traumatic event and the way in which an individual processes it can vary greatly from person to person. Therefore, it should not be assumed that the experience of one or more potentially traumatic events will automatically lead to traumatisation, or that a person is not affected by traumatisation simply because they have not developed clear symptoms. Crucially, trauma is subjective; what one person may consider to be a severe trauma may not be regarded as such by another (Courtois & Ford, 2016). Some situations such as the magnitude of the traumatic event, the way it occurred, its duration and how many people were affected by this event, as well as the person’s own coping mechanisms and previous experiences determine how traumatic this event can be for this person.

Effects on the nervous system and the brain

Traumatic events can change both psychological and physical processes, as the body remains in a state of defence that is no longer present but is still experienced as persistently threatening. Trauma-induced changes affect the nervous system, which is limited in its ability to regulate. Traumatisation can only be processed when the permanent stress reaction has come to an end and the entire organism can operate again from a safe state (van der Kolk, 2023, p. 90).

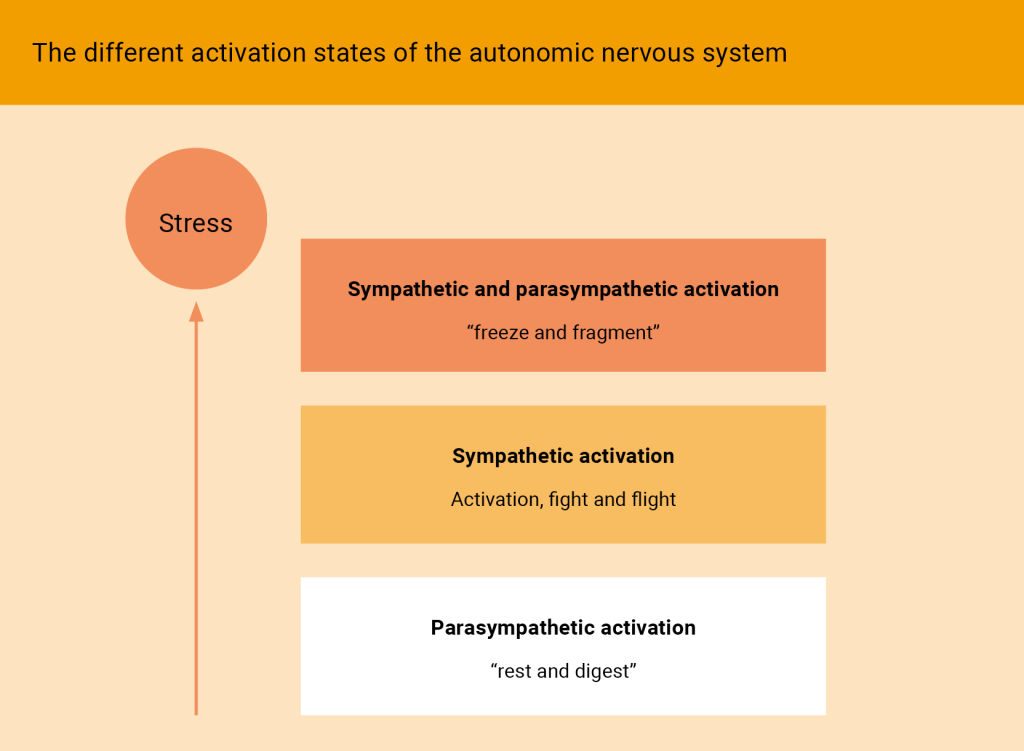

In threatening situations, the stress level arises to enable a person to defend himself. The sympathetic nervous system is activated and stress-related hormones are released in the body. If there is no way out of the threatening situation, the stress level rises further. In the brain control activity is directed to the brainstem and the fight and/or flight response is initiated. This is an automatic response that the person cannot control.

If the danger still cannot be averted, the organism switches to survival mode. In addition to the sympathetic nervous system, part of the parasympathetic nervous system is activated. This puts the body into a state of reduced energy so that the danger can be survived. With the sympathetic system still activated it is as if one were trying to simultaneously accelerate fully and brake fully. This puts the body into a state of “freezing” where reactions are no longer possible and information cannot be processed (Van der Kolk, 2023, S. 135). “In a state of shock, the images disintegrate into fragmentary fragments that concentrate exclusively on the threatening aspects that stand out most” (Levine, 2011, S. 152).

Figure 1: The different activation states of the autonomic nervous system

To be traumatised means to have had one’s boundaries violated. This violation is primarily physical rather than psychological. The nervous system loses its ability to regulate and to adapt. It remains in a state of hyperarousal or hypoarousal and can no longer adapt appropriately to a situation (Levine/Kline in: Jäckle et al., 2017, S. 695). As a result, rapid shifts between states occur and emergency responses such as fight, flight or freeze are sometimes triggered even by minor demands. There is also a risk of using substitute strategies for regulation, such as medication, drugs, alcohol, risky behaviour, overeating or self-harm. Thus a really important and helpful aspect of supporting traumatised people is to help them to regulate their nervous system.

A variety of possible effects of traumatic life experiences on the brain, the body and especially on learning and developmental processes have been identified. All these processes take place very quickly and automatically in the brain. An important part of this is that memory plays an important role in these processes, which is particularly affected by trauma.

In comprehending trauma an examination of the brain and autobiographical memory is essential. This memory can be delineated into two distinct categories: cold memory and hot memory. Cold memory encompasses factual recollections of life-time periods and specific events, typically stored as objective information. For instance, one might recall being in the workshop of the project “All Means All” in June 2023, engaged in discussions about trauma (Huber, 2020). Conversely, hot memory encompasses emotional and sensory recollections, incorporating subjective experiences such as feelings and thoughts, alongside physiological responses like increased heart rate, respiration, or perspiration. Through the amalgamation of these hot memories, a fear network is constructed within the brain. The functionality and even the structural composition of the brain undergo alterations when individuals encounter life-threatening situations, as stress induces changes within the brain’s dynamics.During a situation where flight is unattainable and fighting appears futile, individuals may experience a state of freezing. This triggers an alert within our systems, leading to a disconnection between hot and cold memory networks. Consequently, data regarding the situation may be inadequately stored.

Subsequently, when such individuals encounter stimuli reminiscent of the traumatic event, the fear network is reactivated, plunging them into a state of disorientation commonly known as flashbacks. In these instances, individuals may perceive themselves as being once again in the midst of warfare, experiencing torture, or enduring instances of past bullying by peers.

The symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder can be divided into three groups: symptoms of hyperarousal, caused by the changes in the nervous system described above; symptoms of re-experiencing, caused by the altered storage of the experience in the memory; and, thirdly, avoidance behaviours and withdrawal, so that stress triggers and symptoms of re-experiencing are avoided as far as possible.

According to the currently valid DSM-5, these include the following possible symptoms and behaviours:

| Criterion | Symptom description |

|---|---|

| Intrusion Symptoms (B) |

|

| Avoidance and Negative Alterations in Cognition and Mood |

|

| Marked Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity |

|

by American Psychiatric Association, 2013, S.271f

This is only a rough overview of symptoms; a wide range of other forms of expression of traumatisation can develop, which can then be assigned to these subgroups in terms of their origin. What all forms of expression of traumatisation have in common is that they make subjective sense in the context of the individual’s life experience and, more specifically, the traumatic experience, or at least made sense for survival in an earlier period.

Effects on physical and mental health

Children and adolescents who have experienced traumatic events often exhibit a series of other types of social-emotional and behavioural problems. Although not all children who experience challenging situations develop symptoms of trauma, the majority often have problems with fear, anxiety, depression, anger and hostility, aggression, self-destructive behaviour, feelings of isolation and stigma, poor self-esteem, difficulty in trusting others, substance abuse, and sexual maladjustment among many other emotional and behavioural difficulties. Children who have experienced traumas also often have relationship problems with peers and family members as well as problems with acting out, which leads to difficulty with academic performance.

There are a number of psychiatric disorders that are associated with traumatic experiences. These may include anxiety disorders such as separation anxiety, panic disorder, and generalised anxiety disorder; and externalising disorders such as attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorders (Frieze, 2016).

Trauma can have physical and mental impacts:

In addition to the emotional and psychological difficulties explained above, trauma can have physical and mental impacts. When a child experiences a traumatic event, it can negatively affect their physical development. The stress related to the trauma can impair the development of their immune and central nervous systems, making it harder to achieve their full potential. Because of poor health and poor general well-being, they may experience lack of sleep, lack of appetite or binge eating and poor self-esteem. The children can experience concentration and memory difficulties and struggle to complete learning tasks. These are impacts of trauma and should not be confused with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), or learning disabilities. The child may undergo learning and social-emotional difficulties as a result of the trauma, as their bodies are drained by the traumatic experience (Maercker & Hecker, 2016). These are complex psychological and psychiatric conditions which require the interventions of professional psychologists.

Activity: Think of a big problem you or a friend experienced as a child.

In one paragraph, describe the event. What happened and what caused the problem? How did you or your friend respond/ react? How did it affect your life / the life of your friend? Go back to the list above and select any five impacts you think could have been your or your friend’s reactions to the trauma. Create a table where you write down the term and what it means for example:

| Term/ Impact

Behaviour / Thoughts |

Meaning

Symptoms or Effects of Trauma |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Effects on the educational process

Traumatic experiences undermine students’ ability to learn, form relationships, and manage their feelings and behaviour and place them at increased risk for trauma and a range of negative academic, social, emotional, and occupational outcomes (Rossen & Hull, 2013). If not managed properly, this makes the learning environment unsuitable for all children. Children affected might start to underperform in learning situations, even if they did not present with learning difficulties before. Teachers should refrain from blaming or labelling them. Instead, teachers could conference with the learner and where possible with parents and guardians of the learner showing the above signs to try and understand the issues they are facing. They should try to work on achievable targets with the learner.

Exposure to trauma can “impact learning, behaviour, and social, emotional, and psychological functioning” (Kuban & Steele, 2011, p. 41). Maslow’s hierarchy of eeds suggests that children whose basic needs – such as physiological needs, a sense of security, and emotional needs are not met, are more likely to be unable to concentrate and achieve in school. These children will have difficulties with concentration, memory, application of knowledge and focus. These learners will develop emotional and behavioural problems, which will in turn manifest poor academic performance, with poor attendance and low reading and numeracy levels (https://khironclinics.com/blog/trauma-and-education).

Learners who have experienced trauma may struggle with reading and writing skills, participation in debate and discussion, and solving mathematical and other cognitive problems. The development of each of these skills relies on the brain’s ability to organise, comprehend, remember, learn, trust, and produce work. A big part of cognitive functioning is emotional self-regulation, attention, and optimism demonstrated in a belief in oneself. The ability to control one’s emotions, retain attention, and behaviours are crucial for healthy brain development and personal growth through education (https://khironclinics.com/blog/trauma-and-education). Unfortunately, traumatic experiences disrupt these brain processes and concerted efforts are needed to restore and normalise emotions and functions needed for learning and socialisation.

Here are some examples of how trauma interferes with the brain functions:

- Hindered development of brain areas associated with language and communication

- Jeopardised sense of self

- Compromised ability to pay attention in class

- Reduced memory – difficulty following instructions

- Poor organisation skills

- Difficulty grasping ’cause and effect’ relationships (https://khironclinics.com/blog/trauma-and-education).

Case study

Suppose that you have a 13-year-old boy in your class who recently lost both his parents as a result of COVID-19. Your learner is the eldest of the siblings and has since taken over a parental role over his younger brother (12 years old) and a younger sister (7 years old). These children have no problem accessing food and other basic necessities because their parents left enough resources for them to survive on. However, this eldest child finds it difficult to supervise all the activities at home, including the sibling’s school work. By the time he sits down to focus on his own academic work, he is tired. He comes to class with incomplete homework and sometimes he writes his work in the wrong book.

- Would you say that this boy and his siblings had a traumatic experience? Explain your answer.

- From the list above, what do you think is the specific area of this boy’s brain that is affected by the new role of caring for his siblings?

- Make three suggestions on how you would support this boy in class.

Importance of Trauma-Informed Education

Children and adolescents are the ones who become the victims of traumatic events the most. They are usually school aged children, and if they are lucky, they can attend a school. For instance, the majority of refugees fleeing the Syrian war are children, and the schools they attend are often forced to meet the psychological, social, and educational needs of these children who are victims of war (Sullivan & Simonson, 2016).

Schools are places where students can learn, explore, and grow as individuals. However, a crisis or traumatic incident that occurs within the school community jeopardises the mental well-being and academic progress of pupils (Finelli & Zeanah, 2019). These crises can manifest in many different ways, such as a natural disaster, a war, or the death of a pupil. Crisis situations in schools can be acutely traumatic, but they can also have long-lasting effects on students’ well-being. For instance, psychological vulnerabilities such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are linked to natural catastrophes (Makwana, 2019). Finally, by interfering with students’ metacognitive learning processes, the psychological impacts of trauma can hinder academic achievement (Panlilio et al., 2019). At the same time, stress reactions experienced by children and adolescents in trauma situations make learning almost impossible and also cause behavioural problems at school (Dyregrov, 2004). Therefore, attending to kids’ post-crisis mental health needs may help to lessen the effects of long-term trauma. However, research revealed that many schools lack comprehensive plans for responding to crisis situations (Sokol et al., 2021).

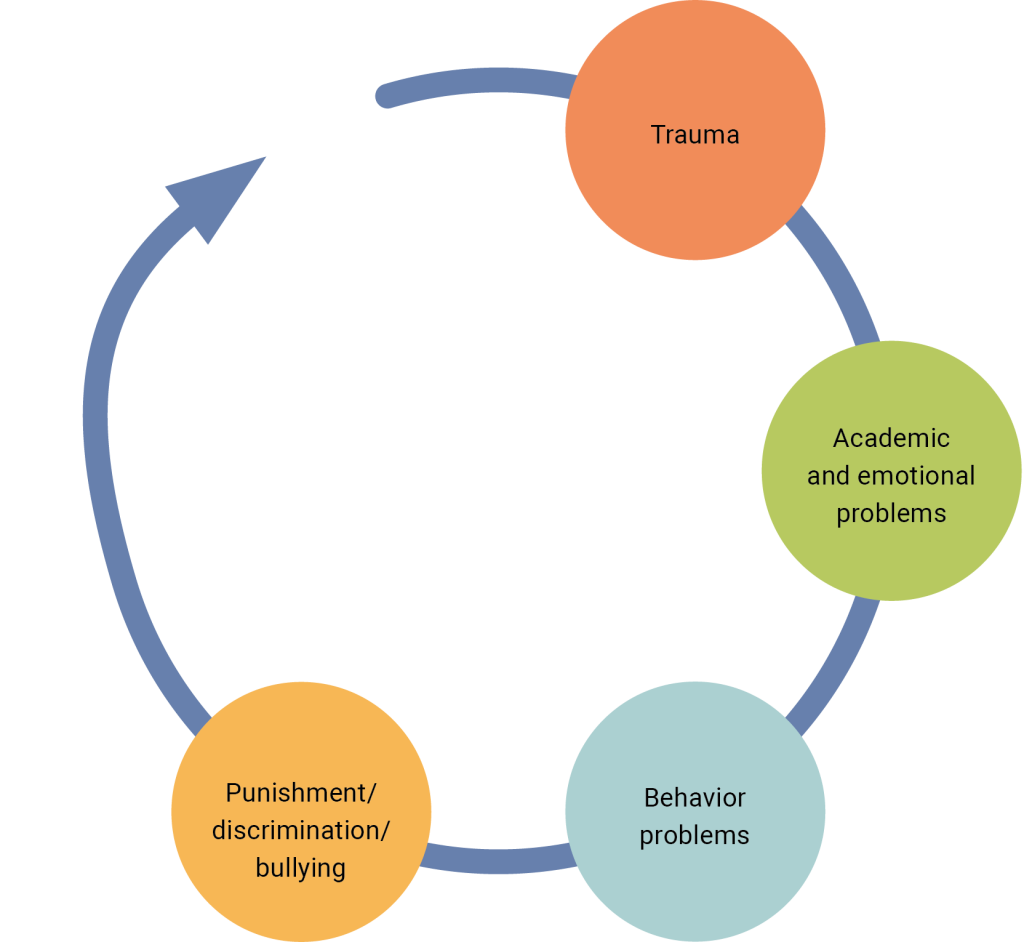

Figure 1 demonstrates the trauma cycle in an educational setting. Children affected by trauma might start to underperform in learning situations, even if they did not have learning difficulties before. They might also demonstrate behavioural problems. If not handled properly by the educators, the trauma cycle continues, and new traumas due to punishments, failure, or bullying may be added to the original trauma. We can say that if not focused/handled properly, trauma can make the learning environment unsuitable for all children. Instead schools should try to work on achievable targets with the learner. Teachers can also confer with the learner showing the above signs to try and understand the issues they are facing. By observing students during lessons and other activities at school, it may be advisable to adjust the educational environment and/or homework according to the specific needs of the learner. The timely involvement of teachers or a child mental health professional, depending on their academic, social or psychological needs, may help to resolve the child’s problem before it progresses further.

Figure 2: Trauma cycle in an educational setting

Schools are critically important settings to intervene and foster trauma-affected children’s resilience. As Weist, Paternite, and Adelsheim (2005) stated, schools play an important role in community-based mental health. Because many children and families can be reached easily, it is a very practical place to implement change. Therefore, considering the effects of trauma on children’s well-being and the role of schools in the community, we can say that teachers and other school personnel should be informed about the trauma.

Trauma-informed education means teaching with the awareness that children go through serious, challenging events, and those experiences can affect learning. has the following characteristics:

- It is a strength-based approach

- It emphasises safety in all aspects for both educators and students

- It creates opportunities for people who have survived trauma to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment (Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, 2010, p. 82).

Trauma informed Interventions

“Trauma-informed approaches in schools must be implemented at all levels, from classroom practices to school policies, in order to create a consistent and supportive environment for students.” (Luthar & Mendes, 2020, p. 148)

In order to establish educational institutions as environments that are responsive to social circumstances which have the potential to cause psychological trauma, it is essential to consider a multi-faceted approach that ensures the safety and well-being of young learners, even in the aftermath of traumatic life experiences. Firstly, educators require trauma-specific knowledge to facilitate individualised relationships and lessons. Given that teachers typically work with groups rather than individuals, there is also a need for opportunities to work with groups in a trauma-sensitive way. Secondly, social awareness and recognition of the factors that cause trauma and the need to take responsibility for this as a task for society as a whole is essential.

Individual-based interventions – Experiencing school as a safe space

After harrowing and potentially traumatising experiences, people also need to feel safe in everyday life. In a trauma-sensitive context, we talk about creating safe spaces. This means not only making the environment in which the person lives safe, it also includes the willingness of the environment to be there in situations of stress, to help with stress regulation, to reorient in crisis situations and to develop a high level of sensitivity to the person’s need for safety. “Schools must create trauma-sensitive environments where students can feel safe and supported, which in turn fosters their capacity for learning.” (Luthar & Mendes, 2020, p. 148).

In order to achieve this, educational establishments must first be prepared to address the consequences and requirements of traumatic experiences. It is also essential to cultivate a trauma-sensitive approach throughout the institution, enabling the identification of trauma-specific indicators and the implementation of trauma-sensitive strategies. “In trauma-informed schools, adults are trained to understand that disruptive behaviours are often not intentional but are rooted in a child’s emotional pain.” (Luthar & Mendes, 2020, p. 148).

There are some general principles and methodological considerations that should be taken into account in schools and in teaching, which will be discussed in the following section:

a) Experiencing a Secure Relationship

Both brain research and therapy research have shown that the main condition for successful trauma processing is the corrective experience of a relationship that provides security. “According to previous empirical knowledge, it can be assumed that the correction of the loss of trust through new, positive experiences about the reliability of relationships is perhaps the most important starting point for dealing with traumatic experiences” (Hüther, 2002, w.p..; translated b.t. authors).

This is not simply about being in the company of other people, but about experiencing reciprocity with at least one person in the sense of being truly heard, seen and responded to (Van der Kolk, 2023, p.132). It is not necessary for this supportive person to be always available; resilience research shows impressively that the willingness to see and support a person is more important than a permanent presence.

Kline (2020, p.120) offers very good guidance on how to create secure relationships and support secure attachment experiences with 8 points:

- Safety, containment and warmth, transmitted through the adults own well-regulated nervous system

- Soft mutual eye gazing

- Shared attention, intention and focus – this is called “attunement” and is experienced as a sincere desire to discover the needs, intentions, and energetic rhythms of the other and to be in synchrony

- Appropriate touch or appropriate proximity, which does not have to involve physical contact

- Soothing voice, rhythmic movement programmes

- Harmonious movements, synchronised movements and facial gestures

- Having pleasure: smile, play and laugh together

- Alteration between quiet an arousing /stimulating activities

When teachers include these aspects in their teaching, new, corrective experiences of security in relationships can be experienced.

b) Support through co-regulation

As described in Chapter 2, traumatic life experiences alter the ability of the stress system to regulate itself appropriately to a given situation. It remains in hyperarousal or hypoarousal or switches between these states. In such heightened states, learning and emotional regulation become difficult. Educators must create an atmosphere where students feel physically and emotionally safe. This includes using a calm tone of voice, controlling body language, and maintaining patience, especially during moments of heightened stress by being regulated of their own emotional states. “Co-regulation, where adults help children manage their emotional states through calm and supportive interactions, is critical in helping trauma-affected children develop the ability to self-regulate over time” (Walkley & Cox, 2013, p. 124).

c) Being sensitive to students’ signals

It is frequently the case that trauma is not conveyed through verbal communication, but rather through vegetative responses that give rise to behavioural patterns, specific requirements or barriers. This refers to the importance of educators being keenly aware of students’ nonverbal cues, such as body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Educators must learn to read these nonverbal signals to gauge how much stimulation or learning a child can handle at any given time. This attunement allows teachers to adjust their approach, providing individualised support that meets the child where they are emotionally. A very helpful question to ask yourself or the young learners is: “Are you doing this/showing this behaviour, because of……?” (Weiß, 2016, p.122f).

d) Being present

Being present means giving attention to students in the moment, ensuring they feel seen and understood. Educators who are mentally and emotionally present with their students help to create a sense of security, which is crucial for building strong, supportive relationships. This mindfulness not only fosters emotional safety but also models healthy relational patterns, which can have a profound healing effect for children who may have experienced inconsistent or harmful relationships in the past.

e) Transparency, predictability, routines and structures

People who have experienced trauma often view the world as unpredictable and unsafe. Establishing predictability in their daily routines can help mitigate this sense of chaos. The principle of predictability emphasises the importance of routine, structure, and repeated positive experiences. When students can anticipate what will happen next, they are more likely to feel secure and less likely to act out due to anxiety or fear (Garner et al., 2012). Predictability also reinforces a sense of control, which trauma-affected children often lack in other areas of their lives. Educators can implement predictability by maintaining consistent schedules, providing clear expectations, and offering regular feedback to help students feel grounded in their school environment.

f) Participation and opportunities for choice and control

If a person has experienced situations in which they have felt completely helpless and out of control in the face of an extreme threat, they need to feel in control at all times. Demands or unclear situations, which are usually difficult or impossible for the learner to influence in a school, can therefore have a triggering effect. For this reason, it is necessary for learners to have the opportunity to shape things that affect them. For example, they need to be able to choose the order in which they start tasks. They also need agreed alternative strategies and emergency signals for situations in which they have no direct choice (Kline, 2020, p. 108).

g) Trauma-sensitive crisis interventions

Trauma-affected children may have difficulty regulating their emotions, which can lead to outbursts or extreme reactions when they feel threatened or overwhelmed. In addition, trauma-related triggers or feelings of insecurity can lead to rapid, uncontrollable increases in stress, resulting in emergency responses such as fight or flight. In such situations, it is crucial for educators not to let their own emotions intensify the situation. “This means that teachers are themselves well-regulated and poised to contain conflict rather than feed the fire of a scared student” (Kline, 2020, p. 147). Instead, staying calm and controlled, even in the face of emotional distress, helps de-escalate the situation and provides a model of emotional regulation for the student.

One crisis intervention that is often necessary is reorientation from flashbacks and dissociation. In addition to the ability to recognise them, this requires methods of reorientation. This means taking the person out of the stressful experience and bringing them back to the sensory reality of the here and now. This can be done by talking to them, by focusing their attention on what they can see, hear and feel, or by using pre-arranged skills.

An example for a step-by-step plan for reorientation:

- Making contact: make contact from a distance (so as not to frighten the other person) by briefly introducing yourself to the person: ‘I am …’.

- Orientation: Briefly inform the person where they are: ‘You are safe here. Today is 23 October 2011 and we are in the living room of the flat at Amselstraße 5.’

- Activation: You can then try to activate the person by giving easily understandable prompts (‘Try as best you can to open your eyes, move your hands …’).

- Further activation: If the first activation is successful, it is helpful to ask the person to look around the room and, for example, to name a given number of objects.

- Self-reorientation: For self-reorientation, the person can now be asked again what their name is, how old they are and whether they know where they are.

- Clarification: The other person is then briefly informed that they have just had a flashback and were in an old film.

- Maintain contact: Then ask if it is possible to make eye contact and maintain contact with the person (Scherwath & Friedrich, 2016, p. 167).

Group interventions

For children or youth who have experienced trauma, there are many group interventions available in addition to individual ones. Group interventions enable the delivery of the intervention to more kids at once. This method of delivery is seen as especially helpful in lower-and middle-income nations, where resources can be especially scarce after widespread traumas like natural disasters or conflict. Even the health systems of developed countries may find it difficult to respond to the needs after mass traumas.When compared to individual evidence-based interventions such as Trauma Focussed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (tf -CBT), group treatments frequently require less training for facilitators (or on-the-job training through the role of co-facilitator), and can be provided by non-mental health professionals. This allows a greater number of children to access support (Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; UNICEF, 2021).

The effectiveness of group-based therapies was examined in a recent meta-analysis (Davis et al., 2023). A total of 42 studies involving about 5998 kids (aged between 6 to 18 years) were included. In comparison to no treatment, the study indicated that such interventions, particularly those based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), were effective in reducing trauma symptoms and depression. There was proof of effectiveness when given to a variety of trauma-exposed groups, including those exposed to war or conflict, natural disasters, and abuse, in extremely complex and resource-limited contexts. The authors of this study also concluded that the results of the study have important implications for contexts in which group programmes may be the most or only viable option, including communities exposed to conflict or natural disasters and poorly resourced services. While individual tf-CBT remains the best-evidenced treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) in children, our meta-analysis demonstrates that group programmes are also a valuable therapeutic resource.

Some of these CBT based trauma-focused group interventions are translated and adapted to different cultures. Tf-CBT in group format usually 12 sessions, Deblinger, Pollio, & Dorsey, 2016), Teaching Recovery Techniques (TRT, usually 5 sessions, Children and War Foundation, 2002-2018), and Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS, usually 10 sessions, Jaycox et al., 2012) are the most commonly used programmes. These programmes also include parent/caregiver sessions.

In order to give an example, the outline of the TRT intervention that was developed by Children and War Foundation will be briefly presented here. The Children and War Foundation develops and disseminates effective psychological procedures for helping large numbers of traumatised children by teaching techniques to recover from trauma. They have developed five manuals to help children cope with their reactions to war, disasters, and violence. The names of the manuals are, Children and War Manual, Children and Disasters Manual, Children and Grief Manual, Writing for Recovery Manual, and Manual for Children Between 4 and 8 Years. The Teaching Recovery Techniques (TRT) manual is based on the A-B-C model (Thoughts and memories, Feelings, and Behaviours) of CBT and includes five group sessions for children and adolescents and two parent sessions. The main goal of the program is to show the children that their reactions are normal for their situation and that they are not going crazy. Specifically the goal is to give children skills to regain control over their thoughts and feelings and be able to remember without being overwhelmed. There are several studies that prove the effectiveness of TRT. For instance, Barron et al. (2013; 2016) and Qouta et al. (2012) implemented it after war in Palestine; Chen et al. (2014) used it for traumatic bereavement in China, Ooi et al. (2016) implemented it after war in Australia, Pityaratstian et al. (2015) used it after natural disasters in Thailand.

Community-Based Interventions

Statistical evidence indicates that a significant proportion of individuals experience traumatic events throughout their lifespan. The social implications of trauma, traumatisation and the ways in which these can be addressed are therefore also worthy of consideration. In this context, it is pertinent to examine how society can enhance awareness of these issues, how it can facilitate effective responses and what options are available.

It is imperative to begin by establishing a culture of openness and communication. It is essential that within a society, there is an understanding of the emergence and consequences of trauma. In order to make grievances visible, it is necessary to create spaces in which trauma can be addressed. It is very important that those who have suffered are afforded the opportunity to articulate their experiences. The following section will examine the issue of sexual violence in Germany in closer detail.

In Germany, following the revelation of numerous scandals concerning the sexual abuse of children and young people in educational institutions, a commission was established to investigate these incidents. The Federal Ministry of Education and Research allocated funding for research into sexual violence, with the aim of facilitating further investigation and reappraisal of the issue. The commission provides a forum for those affected to articulate or document their experiences. Furthermore, it serves as a representative of the affected parties within society. The objective is to elucidate the structural conditions that facilitated the occurrence of the abuse. It would be beneficial for contemporary social sectors to adopt a similar approach. One consequence of these endeavours in recent times is discernible in the Child and Youth Welfare Act (KJSG), which mandates that institutions engaged in the care of children and young people must possess a binding violence prevention strategy.

It is of the utmost importance for societies to establish structures that render the occurrence of man-made trauma an improbable outcome. Conversely, it is imperative that instances of trauma are brought to the fore within society, and that those affected are provided with the requisite assistance and backing.

Empowering Teachers with Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Why should teachers and other educational personnel be empowered in trauma-informed education?

Trauma-informed education provides teachers with the tools to effectively manage traumatic stress, facilitates the provision of comprehensive support to other members of the school and education community, and enables the delivery of targeted training and skills development. A school-wide trauma-informed education approach has been demonstrated to enhance students’ sense of comfort (de Stigter et al., 2024).

It is incumbent upon educators to be conversant with the following areas:

The objective is to provide guidance on how to respond to the needs of students who have experienced trauma. The regulation of stress levels is a crucial aspect of maintaining mental health and well-being in educational settings. This can be achieved through a combination of school- and classroom-based methods. The first objective is to establish school as a secure environment. The second objective is to determine the most appropriate course of action to take when a student is experiencing a crisis or a stressful situation.

Furthermore, the curriculum encompasses a range of additional methodologies, including stress management, classroom management, anti-discrimination activities, peer bullying prevention, and numerous other subjects.

The remaining contents include the definition of trauma, its various types (such as those resulting from war and migration, child abuse and neglect, natural disasters, loss and mourning), the causes of trauma, the symptoms of trauma, the short- and long-term effects of trauma, and the effects of trauma on the learning process. Additionally, the course addresses how to respond to trauma. The training will equip teachers and school administrators with the knowledge and skills to identify and respond to the needs of children exhibiting symptomatic behaviours in the educational environment. This will include guidance on positive discipline, classroom management, in-class psycho-social support activities, peer bullying and anti-discrimination activities.

Why teachers’ well-being is important?

Being a teacher is already a stressful role and there is always a risk of burnout. So many things are going on in school and teachers usually receive little or sometimes no support at all. Teachers are usually the ones who do the heavy emotional work and this leads to stress and burnout. As teachers are charged with constantly balancing multiple responsibilities, there is generally little deliberate attention to their own emotional well-being, thus threatening abilities to withstand the continuing stressors that come with their demanding work lives (Richards, Levesque-Bristol, Templin, & Graber, 2016).

In the literature, it is stated that people involved in the education and rehabilitation process of traumatised children are affected by this experience, both positively and negatively. Positive effects are mostly related to post-traumatic growth, resilience, and satisfaction, and they are called vicarious post-traumatic growth, vicarious resilience, and compassion satisfaction. However, there are some other effects that are negative, such as secondary trauma and burnout. These negative effects not only affect the individual person (teacher or helper) but also other systems (education, organisation, NGO, etc.) and individuals (other students and family members of the teachers and helpers). Neglecting teachers’ psychological health is problematic because this can greatly affect their students (Schonert-Reichl, 2017). It should be something like wearing the mask yourself first and then helping your children in a flight.

The literature also provides some information that people who contribute to helping processes neglect their own self-care (Figley, 1995; Stamm, 2010). In many countries, teachers delivering trauma-informed education (life skills teachers, teacher counsellors, school counsellors, etc.) lack facilities where their emotional well-being can be restored. It is also important to note that dysregulated teachers cannot support dysregulated children. It is advisable for educators to seek therapeutic support when triggered by behaviour or trauma responses within the classroom. Thus, it is very important for those who provide services to traumatised people to be informed about the importance of self-care and to use self-care skills in their lives in order to maintain their well-being.

Self-care encompasses all the actions that individuals take to protect their well-being and to cope with stress effectively. Professional self-care of therapists or people who provide support to traumatised people can be defined by Wise and Barnett’s (2016) definition. Self-care is the routine behaviours that individuals consciously perform in order to protect or improve their physical, emotional, social and spiritual well-being in their professional life.

Showalter (2020) listed the activities that need to be done in order to improve the level of self-care as follows. Staying calm, being aware of feelings, thoughts and behaviours and experiencing them in the present moment, meditating, exercising, eating regularly, spending time with loved ones, sleeping regularly, taking time to rest, appreciating oneself and what they are doing, accepting the difficulty of providing assistance. Sholter (2010) also shared a list of what not to do. This list includes: working harder than usual, giving up on leisure activities and personal needs and interests, ignoring the problem, complaining, blaming coworkers, quitting to look for another job or looking for surface solutions.

Lastly, educational staff or people who provide help are also human beings and must accept this and continue to work according to their own well-being. Especially after traumatic events which affect so many people at the same time, such as earthquakes, legally and ethically, it is not appropriate for people to offer help by neglecting their own well-being. In the same line, legal authorities should not expect them to help others or continue their work while they are not feeling well.

Conclusion and Questions

This chapter provided insights into the situations that lead to trauma among children across the globe. We further unpacked the concept of trauma, the types of trauma and its effects on the brain and aspects such as physical and mental health on individuals and their significant others. We provided examples of trauma affecting children from the perspective of four different countries. We mainly focused on trauma-informed education and its application in inclusive and democratic schools. We explained the concept in terms of its meaning, both subjectively and objectively and provided guidelines to teachers on how to use trauma-informed education. We also provided information on the importance of teacher-wellbeing in the process of providing psycho-social care and support to their learners.

We concluded that trauma among children is a widespread phenomenon and should be treated with sensitivity. Learners from diverse cultural backgrounds perceive trauma differently. Teachers should observe their learners carefully and be aware of their own biases. It is important to note that there is silence around issues contributing to trauma amongst children, especially the man-made and environmentally created traumas. Learners might not disclose, and therefore, teachers must be attuned to notice inner-suffering of learners and attempt to support them through the process by using culturally relevant and inclusive trauma-informed approaches. Some learners develop PTSD and they would need further support from schools and communities. Such support can only be provided if schools and communities can work together in the minimisation of the trauma effects and the prevention of primary and secondary trauma.

While teachers have a responsibility to respond to the needs of their learners who experience trauma, they should be conscious of their own emotional well-being and seek support they may need to continue with their demanding responsibilities toward learners who undergo traumatic experiences. The chapter ends with recommendations to increase awareness on trauma-informed education and to enhance teachers’ capacity to deal with traumatisation emanating from changing societies.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- Which aspects of trauma-informed education are already being implemented in your school?

- What changes does your school need to make to become a trauma-informed institution?

- Is there anything you would like to change in order to work in a more trauma-sensitive way?

- What social necessities do you see to break the silence about trauma in society and in institutions?