Section 5: Inclusive Teaching Methods and Assessment

Universal Design for Learning

Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; and María Pilar Gray Carlos

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

This practical example provides a possible template that teachers can follow to plan their learning and teaching. Column 1 represents a learning activity designed for a Science class adopting a rather traditional approach. Column 2 describes the same activity but planned according to Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles and guidelines. Column 3 specifies which aspects of the UDL-framework are tackled by the changes made in the UDL-plan.

Table 1: Template for Planning Teaching Activities Using Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

| Non-UDL | UDL | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Objective(s) | ||

| The students will write the name and the correct functions of each cell part. | The students will be able to correctly identify each cell part and describe its functions. | The goal is written as to provide flexibility so that students will have choices for how the goal is to be achieved. |

| Learning Activity | ||

| The teacher introduces the information about the cell parts and functions using a PowerPoint with text (frontal lecture). Afterwards students are asked to create cell models with cookies and decorations.*Materials available: cookies, icing, decorations.*Physical space: students sit in their assigned seats. |

The teacher introduces the information about the cell parts and functions using a PowerPoint with text, pictures, video clips (frontal lecture). After that, students examine and discuss in pairs 3D cell models. The teacher then asks the students to name cell parts and describe their functions. To carry out the activity, students can choose to work individually, with a partner, or in a small group. Moreover, they can choose among what “product” to create: a cookie model, a poster, 3D models, a song, a video, an interactive web-based program on cells, other (get teacher approval).Materials available: cookies, icing, decorations, poster boards, writing utensils, computers, and iPads with needed software/apps.Physical space: tables, desks, computer stations, open spaces. |

Provide options for perception. Foster collaboration and community.Foster collaboration and community. Optimise individual choice and autonomy. Use multiple media for communication. Use multiple tools for construction and composition. |

| Evaluation | ||

| Given a worksheet, students will fill in the blanks by writing names of cell parts and their functions. |

Students will have the following options:

|

Optimise individual choice and autonomy. Use multiple media for communication. |

Adapted from Murawski & Scott, 2019, pp. 176-177

Initial questions

In this chapter you will find the answers to the following questions:

- What is UDL’s framework?

- What is variability and neurodiversity?

- How does UDL support my Planning, Teaching and Learning, Feedback and Assessment?

Introduction to Topic

What is UDL?

This introduction to Universal Design for learning (UDL) describes the concept of UDL and its three principles of Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression. It talks about variability, a key concept underpinning UDL, and how neurodiversity is defined within the context of UDL.

The UDL Guidelines were first introduced by CAST in 2008 as a framework to improve and optimise teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. The guidelines have evolved through several iterations, with the latest being UDL Guidelines 3.0, released in July 202412. UDL Guidelines 3.0 emphasises creating inclusive and flexible learning environments by addressing barriers rooted in biases and systems of exclusion. It integrates asset-based approaches and theoretical frameworks, focusing on learners’ multiple and intersecting identities. This version shifts from educator-centred to learner-centred language, promoting interdependence and collective learning. Since its inception, the UDL framework has been dynamic, continuously developed based on new research and feedback from practitioners. Each update has aimed to better honour and value every learner, ensuring that all can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities. Universal Design for Learning is a change in mindset and a framework for inclusion. UDL is a proactive approach to learning, teaching, and assessment design that supports the varied identities, competencies, learning strengths, and needs of every learner in our classroom and school community. The UDL Guidelines are the tool to support inclusive practices in our learning environments. They do this by providing opportunities to offer a variety of pathways (choice and flexibility) to learners to ensure that:

- Learners understand the lesson content

- Goals are clear and specific to the expected outcome

- Assessment is flexibly designed to facilitate every learner to communicate and demonstrate their learning, knowledge, values, and skills through a variety of formats (Meyer et al., 2014).

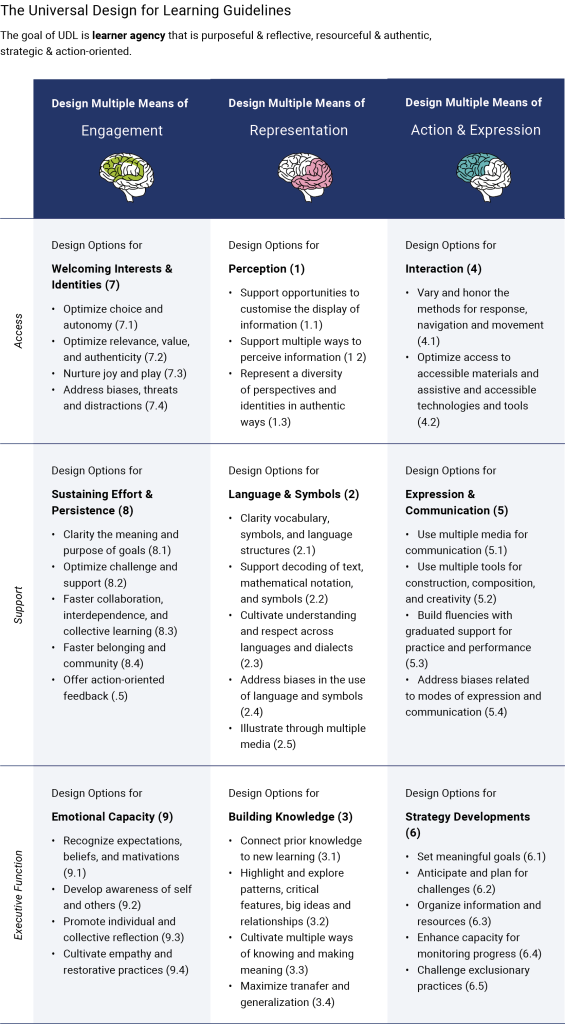

UDL highlights three design principles that provide a map for teachers: Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression. The UDL Guidelines offer recommendations, or checkpoints, for enacting each UDL principle (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: UDL Guidelines by CAST.

Multiple means of engagement

Learners differ greatly in the ways they can be engaged or motivated, and that external factors can impact on this. Thus, teachers need to ask: How can, and will, our learners engage? In order to facilitate learner engagement, variability needs to be considered. A variety of elements can influence how learners engage, including neurology, culture, personal relevance, subjectivity, and background knowledge. The diverse needs of learners requires that numerous engagement strategies are employed to support every learner in every context. For example, some students may not be interested or ready to participate straight away. Some will tire easily because of the physical or cognitive effort involved in achieving the learning goal whereas others will look forward to the practical elements. If teachers provide multiple, intentionally designed options for engagement, then each learner is offered a way into their learning (CAST, 2024).

Multiple means of representation

Learners perceive and comprehend information presented to them differently. Thus, teachers need to ask; how will learners perceive the content presented to them and how can the content be best presented in a way that provides access for each learner to engage with learning? Like engagement, there is not a one-size-fits-all means of representation. Some will not have sufficient access through text and will process information better through visual or auditory means. Others will enjoy independently exploring the content. Some will work better if they can access instructions in stages as they work through the content or task (CAST, 2024, Flood & Banks 2021).

Multiple means of action and expression

Every learner navigates their learning environment and expresses what they know differently. Thus, teachers need to ask; how can learners best act on their learning and demonstrate their knowledge, learning, values, and skills? Are learners given the opportunity to show their best selves? There is no one means of action and expression. Rather, it is about being clear on the goal of the task and providing those intentional options to learners that enable them to achieve. Some will not know how to start a task or how to express themselves clearly, or they may be unable to plan their actions. Others will have a system for planning their actions and will easily craft an essay, project, or presentation to display their knowledge. Some may be able to express themselves well in writing but not speech, and vice versa. Thus, if only one act of expression is offered to learners, they may feel they will not accomplish the task well. (Cast, 2024; Flood & Banks 2021).

Designing for Variability

For teachers, there may be a fear around inclusive practices and how to design for the inclusion of every learner in class sizes of up to 30 learners. UDL encourages moving away from a learning approach which focuses on? lesson design, in terms of ability and disability, to one which promotes? variability. Through this UDL mindset, learners are not labelled by their disability, social background, gender, race, and so on, instead the approach involves all learners? Variability recognises not only the diversity in a group of learners but also the variability within each learner. It considers the ‘jagged profile’ (Rose, 2016) as a more comprehensive way of identifying a holistic view of our learners’ strengths and areas for support. This jagged-profile approach to variability pays attention to context and the environment that facilitates intentional design to remove barriers to learning.

Neurodiversity

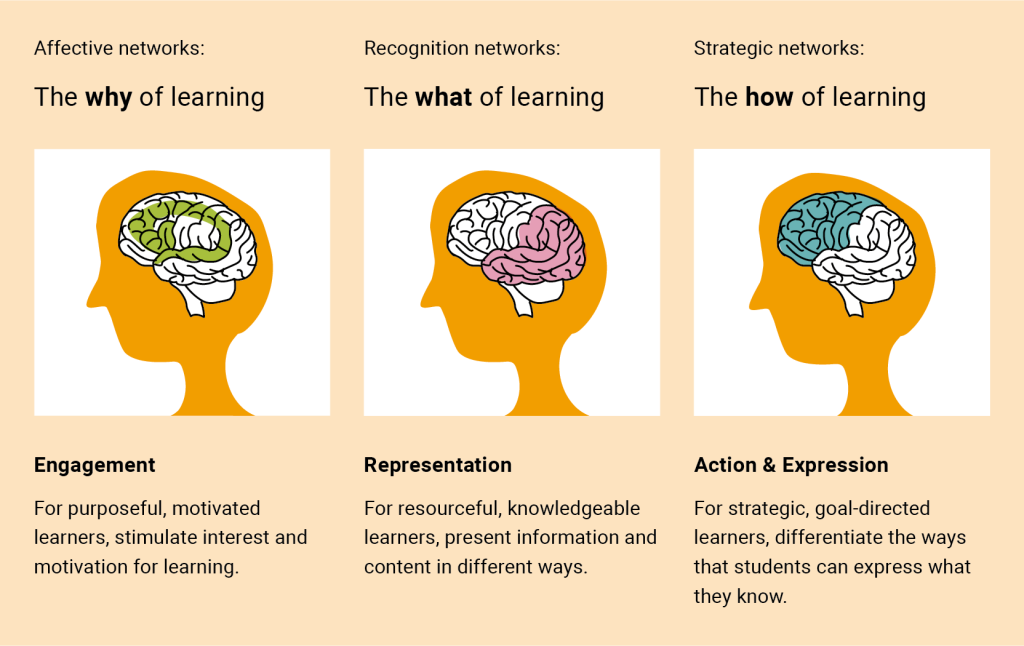

Variability is a dominant feature of UDL because it is the dominant feature of the nervous system (Meyer, Rose & Gordon, 2014). Neurodiversity in UDL recognises that there is no single way that a brain will respond to the learning environment. Because there is no ‘average’ brain and therefore no ‘average’ learner, teachers need to stop planning, teaching, and assessing based on that idea. UDL recognises that there are goals which drive the nervous system. Thus, the brain is divided into three strategic networks (see Fig. 3) that the UDL principles were designed around:

- The Affective Networks (Engagement), which is the how of learning

- The Recognition Networks (Representation), which is the what of learning

- The Strategic Networks (Action and Expression), which is the why of learning.

Figure 3: The three UDL strategic networks by CAST.

The UDL Guidelines, and associated checkpoints, correspond to the nervous system and brain structure in order to help teachers address the predictable variability in learning that will be present in any environment (CAST, 2018; Meyer et al., 2014).

Key aspects

The following three main sections – Planning, Teaching and Learning, and Assessment and Feedback – provide a general overview of how UDL supports inclusive teacher practices. Each section follows the same structure. Initially, we briefly outline how these key aspects are conceptualised within the UDL-framework. Options are then considered in order to deepen understanding of each topic with relevant examples on how to enact the three UDL principles for both in-person and digital learning environments. For modelling UDL-principles, two alternative tables (A and B) will be provided for the two settings (in presence and online/hybrid) respectively, from which the readers can choose according to their own needs and/or interests.

Planning

A key priority is to understand that UDL is goal driven. Teachers need to focus on the learning outcome of a particular lesson or indeed a unit of lessons. Only once the goal is clear and specific to the learning outcome, can the teacher identify barriers to learners achieving this outcome. In other words? once these barriers are identified, teachers can then design their lessons to remove them. This may appear as an onerous task involving planning for each individual learner separately, however, this is not the case. As UDL is designed around the connection between the three learning networks of the brain, variability can be predicted, hence learning can be intentionally designed for (Myer et al, 2014). A practical example of this is planning a lesson to debate the pros and cons of the plastic bottle. The teacher knows the goal is to debate/form an argument. However, writing a paragraph on the topic is the required goal. Consequently, students now face a barrier as the lesson plan has not considered the variability of the learners. There are barriers for students who may find writing a challenge, might have dyslexia, may be slow writers, or for whom English is not their first language. In this case, the teacher can create specific choices or pathways for students (e.g., an oral or poster presentation or a written presentation) which is designed to offer them a variety of means to meet the goal of debating.

It is also important to note that to support variability in learners’ options for Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression must be integrated at the planning stage so that they can be put into practice at the later stages.

Table 1a: UDL-Planning for in-person learning contexts.

| UDL-Planning for in-person learning contexts |

| UDL planning is goal-driven. That is, once the intended learning outcome for a unit of lessons is defined, teachers will then need to consider how to address their learners’ variability to remove eventual barriers to its achieving (Meyer et al., 2014). To do that, teachers must guarantee accessibility of teaching and learning and design different options for their learners to choose from. This includes methods, materials and assessments used to teach the lesson. In-person situations allow for a variety of solutions, given that learners can interact both with their classmates and with the physical environment surrounding them. In the following, we will see how teachers can apply UDL to their planning for in-person learning contexts in relation to its three underpinning principles.

Remember that planning is about anticipating variability and removing barriers. It is about naming and sourcing the strategies and choices for the lesson to be prepared and applying them to teaching, learning, assessment and feedback. A helpful resource for planning with UDL in mind is this step-by-step lesson planner (Posey, no date). |

EngagementPractical approaches to engagement in lesson design include:

|

RepresentationPractical examples for Representation include:

|

Action and ExpressionPractical examples for Action and Expression include:

|

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Table 1b: UDL-Planning for digital learning environments.

| UDL-Planning for digital environments |

| To properly implement UDL, teachers must guarantee accessibility of teaching and learning and design different options for their learners to choose from. This includes the methods, assessments and materials used to teach the lesson. Technology provides wide support for teaching and learning situations that can take place both in hybrid or blended contexts (in-person and online) and in asynchronous and synchronous contexts.

Digital technologies can support, enhance, and facilitate in each stage of the three UDL principles. UDL provides a frame of work to help teachers in their planning, enabling them to include digital resources to support students in achieving the intended learning goals. It is important to note that the application and use of UDL principles do not require a mastery of all technologies and digital resources available in the market. Purposeful, user-friendly digital tools are widely available. The aim is to choose one at a time, and work with essential tools that best support the access to the content, the delivery method, appropriate and timely feedback, and student engagement as well as the opportunity for students to show what they have learnt through mediums that best support their expression. Planning is about anticipating variability and removing barriers. It is about naming and sourcing the strategies and choices for the lesson to be prepared and applying them to teaching, learning, assessment and feedback. A helpful resource for planning with UDL in mind is this step-by-step lesson planner (Posey, no date). |

EngagementPractical approaches to engagement in lesson design includes:

|

RepresentationIt is important to make content-related input comprehensible.

|

Action and ExpressionDigital tools are the perfect medium to give students varied ways to express what they have learnt.

|

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Teaching and Learning

Firstly, teaching and learning must take into consideration the student, environment, curriculum, context, cognition and emotions. When planning for choice and flexibility, teachers need to ensure that the options planned will work in practice. Thus, teaching and learning follows on from intentional planning with the intentionality continuing into practice. Teachers will have a range of choices they can include in their lesson. Nevertheless, the teacher must clarify the goal and then intentionally choose the options that will work best in a specific lesson and context.

Think about this in terms of a GPS on phones. When we enter the destination, GPS provides an option that allows flexible routes to reach the destination. Firstly, it offers modes of transport. Then, it offers a variety of route options and highlights barriers or challenges – such as delays along the route. Once the preferred route is chosen there are options to preview the route in advance, use the written steps, visual map, audio directions, or a combination of options. Once enroute, GPS will adapt the journey. For example, if there is an unforeseen barrier e.g., a traffic jam, GPS will offer the choice of staying on the planned route or taking an alternative one. Regardless of the means, routes, and detours taken you still arrive at your destination. This method can be similarly applied to UDL in terms of teaching and learning. Furthermore, remember that the ‘current location’ or ‘starting point’ will be different for every traveller, as are the travel choices made. However, the destination goal remains the same, reinforcing the intentionality of choice?

Table 2a: UDL-Teaching and learning in in-person learning contexts.

| UDL-Teaching and learning in in-person learning contexts |

| UDL teaching and learning reflects, and puts into practice, the intentionality of planning envisioned in the framework to address learners’ variability and create barrier-free learning environments. As shown in the previous section, this intentionality translates into the design of multiple options for Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression. Teaching and learning is about implementing these options in class and making sure they actually work. This involves facilitating the lesson, monitoring, and feedback on learners’ progress (Posey, no date). |

EngagementPractical approaches to support learners’ interest, effort, and self-regulation are:

|

RepresentationTeachers should present the information in varied formats (e.g., when introducing a new concept, unit, etc.) which resonate with learners’ different strengths and preferences for processing information – such as a lecture, activity-based exploration, or demonstration (Jackson & Harper, 2006). Practical examples for presenting lesson content in class include:

Additionally, teachers should always ensure to provide alternatives for perception (visual, auditory, and written) and to support students’ understanding and decoding of language, symbols, etc.

|

Action and ExpressionTeachers need to provide their learners with a range of different assignments/tasks and tools to ensure flexibility in the ways in which they can demonstrate their skills, understanding and knowledge. Practical examples for this include:

o individual charts to follow the activity flow o guide sheets explaining procedures o subdividing the topic area into subtopics o access to a peer expert

o spell and/or grammar checkers o word prediction software o text-to-speech o speech-to-text software and apps (e.g., Voice Note) o note-taking apps (e.g., SoundNote, Notability) o concept mapping tools (e.g., Popplet). |

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Table 2b: UDL-Teaching and Learning in digital learning environments.

| UDL-Teaching and learning in digital environments |

| UDL teaching and learning puts into practice the intentionality of planning envisioned in the framework to address learners’ variability and create barrier-free learning environments. As shown in the previous section, this intentionality results in the design of multiple options for Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression. Teaching and learning is about implementing these options and making sure they actually work. Technology enables people to meet and connect together synchronously (Zoom, Google Hangouts, Skype, Google Docs) and also allows students to work in their own time and place independently with asynchronous tools (Google Classroom, Seesaw, Edmodo, Canvas) and support hybrid and blended situations as well. |

EngagementPractical approaches to support learners’ interest, effort, and self-regulation include:

|

RepresentationTeachers should present the information in varied formats (e.g., when introducing a new concept, unit, etc.) which resonate with learners’ different strengths and preferences for processing information – such as in the case of a lecture, activity-based exploration, or demonstration (Jackson & Harper, 2006). Practical examples for presenting lesson content in class include:

|

Action and ExpressionTo ensure flexibility in the ways in which learners can demonstrate skills, understanding and knowledge, teachers need to provide them with a range of different assignments/tasks and tools they can choose from. Practical examples for this include:

|

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Assessment and Feedback

When the teacher is clear about the lesson? goal, and has facilitated flexibility and choice of how to learn, providing choice and flexibility in how to communicate this learning is a natural step. Assessment from a UDL lens means that teachers need to think about assessment and feedback from the students’ perspective. They need to ask how learners can best communicate through language or actions, and facilitate their understanding, knowledge, skills, and values around the learning experience. The objective of an assessment is often a written exam. However, if the goal is not necessarily written?, then a written exam can be a barrier for many learners, with the result that teachers do not fully capture the learners’ capability. By offering learners more choice such as writing or presenting an oral presentation, creating a movie or podcast, role play, learners can present their work in a way that best suits their needs and ability. An example of this is assessing a lesson on character development. The default mode of assessment would be to ask learners to write a paragraph or essay outlining how the character has developed throughout the play. However, if the teacher is clear about the learning outcome – understanding character development – then it becomes clear that just writing alone can be a barrier. Thus, the teacher intentionally offers other assessment choices; the learner can choose to write, role play, or create a poster. What if a learner approaches and asks for a fourth option, to do a comic strip. While it wasn’t an intended choice it supports achieving the specific learning objectives. The outcome is that the learner can express their knowledge and learning according to what suits them. The teacher then learns the competency level of the learner and can readjust expectations or offer support based on this new understanding, rather than what they previously demonstrated/attempted?. Additionally, the teacher may learn of a talent or interest of the learner that can be used to engage them in further learning experiences.

This example also highlights the value of feedback, particularly from students / and the importance of student input? When students feedback to teachers and the teacher acts on this feedback, it communicates to the learners that they have a voice in and responsibility for their own learning. It is important that feedback, like assessment, is formative which can be teacher or student led. Finally, it is important that feedback is constructed to support and challenge learners in a learning process, and not label their general learning competency based on a specific moment in time.

Table 3a: UDL-Assessment and Feedback in in-person learning contexts.

| UDL-Assessment and feedback in in-person learning contexts |

| CAST (ref) highlights that methods and materials used in assessments often require skills and understanding that are not relevant to measure learners’ knowledge, skills, and abilities, but which may also pose barriers. As such, they should be minimised by providing learners different supports and options on how to demonstrate what they have learned. Once the learning objectives – and thus the focus/construct for the assessment – are clear, then there can be flexibility in the assessment options insofar as they align to and measure the intended goals/constructs.

Thus, applying the three UDL principles to assessment means offering flexible options in how the assessment is represented, how learners can show what they know, and how they engage in the assessment process (CAST, 2015). This applies both to formative and summative assessments. However, UDL puts particular emphasis on the importance of formative assessment as an essential part of the learning process, insofar as it is intended to monitor learners’ progress and to inform and adjust instruction during its course (Meyer et al., 2014). This kind of assessment is not only is useful for teachers to collect evidence about their students’ progress, but importantly, allows students themselves to learn about their own performance and that of their peers. In this way, they become a proactive part in monitoring their progress and are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning. Feedback plays a crucial role in this respect and constitutes a key feature of UDL for addressing learners’ variability. By being goal-oriented, relevant, timely and specific it is indeed meant both to guide each learner towards mastery and to inform teachers’ instructional practice. |

EngagementIncreasing learners’ engagement in assessment can enhance their performance. Practical strategies to do this include:

To engage learners in the learning process, ongoing, relevant and mastery-oriented feedback is also essential. Opportunities for feedback are:

|

RepresentationApplying the principle of Representation to assessment means considering how the information and content of the assessment task are presented. Options for presenting assessment items and instructions include:

Alternatives for perception (visual, auditory, and written) and support for understanding and decoding of language, symbols, etc. should be offered in assessment too. Strategies for this include:

|

Action and ExpressionTo get accurate data regarding students’ knowledge and capability, teachers should provide multiple means of response and multiple opportunities in varied media for them to demonstrate their skills, understanding and knowledge. For example, written assessments may allow different question/answer formats, such as:

However, if written production is not the measured construct, then alternatives should be offered to complete the assignment. These may include:

UDL assessment also provides support on construct-irrelevant dimensions. Examples of different support tools and scaffolds are:

|

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Table 3b: UDL Assessment and Feedback in digital learning environments.

| UDL-Assessment and feedback in digital learning contexts |

| CAST highlights that methods and materials used in assessments often require skills and understanding that are not relevant to measure learners’ knowledge, skills, and abilities, and which may also pose barriers to learning. As such, they should be minimised by providing learners different means and a variety of options to demonstrate what they have learned. Once constructive alignment (Biggs 1996) and working through content provides a clear idea on how students can be assessed, the assessment is measured and the means of assessment production are supporting expression and individual needs. Thus, applying the three UDL principles to assessment means offering flexible options (and therefore choice) in how the assessment is represented, how learners can show what they know, and how they engage in the assessment process (CAST, 2015).

Feedback constitutes another key feature of UDL for addressing learners’ variability. By being goal-oriented, relevant, timely and specific it is indeed meant to guide each learner towards mastery. |

EngagementIncreasing learners’ engagement in assessment can enhance their performance. Practical strategies to do this include:

Feedback is very important at every step of the course and in any lesson, in particular in online environments where physical presence of the teacher is reduced, mechanisms for following up, checking and supporting progress are needed. |

RepresentationApplying the principle of Representation to assessment means considering how the information and content of the assessment task are presented. Options for presenting assessment items include:

|

Action and ExpressionProvide different options to complete the assignment:

Written tests may allow different question/answer formats (Google Forms, Moodle and Blackboard assessment tools), such as:

Both in-person and online (blended, hybrid, asynchronous or synchronous) teachers should always plan for different support tools to reduce the measurement of construct-irrelevant factors. |

by Margaret Flood; Anna Frizzarin; María Pilar Gray Carlos

Closing

We began this chapter introducing UDL as a ‘shift in mindset’ which proposes the proactive and intentional design of learning environments which are responsive to learners’ differences. Inclusion and participation in learning is thus enhanced in this framework via the design of methods, materials and assessments used to teach the lesson that are flexible and accessible for all learners. The focus on the accessibility of teaching and learning constitutes indeed a key feature of the UDL approach and reflects a shift of perspective from what students can/cannot do (with respect to the “average”) to the contextual barriers that may prevent them from succeeding in learning. This marks a pivotal change, insofar as it implies the recognition of the role of the environment in hindering learning progress and learners’ active engagement in it, moving beyond labels and categories (and thus overcoming a medical/deficit-oriented perspective on disability and difference; Meyer et al., 2014). Moreover, the emphasis on flexibility and choice enables the implementation of a differentiated instruction – and thus individual learning paths – for all, avoiding the risk for some children of being stigmatised for their need of special accommodations.

In this sense, the UDL framework can be seen as a driver of inclusion and equity. The inherent flexibility and choice allows a more equitable education by acknowledging, embracing and celebrating students’ unique identities (with all their intersections) and providing them with all they need to succeed in their learning (Chardin & Novak, 2020).

At the beginning of this chapter, we set out three questions to answer for teachers. The next step is for you to ask and answer this question in relation to your practice: ‘How can I use UDL to support and challenge the learning of every student in my classroom?’

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- How does viewing UDL as a “shift in mindset” from deficit-based approaches to removing contextual barriers change the way you design and implement lessons?

- Looking at the example case provided, which specific UDL modifications (e.g., choice boards, alternative formats, varied assessment methods) do you believe most effectively bridge the gap between traditional and UDL-informed teaching?

- Considering the emphasis on formative feedback in the chapter, how can you use both student and peer feedback to refine and adapt your UDL practices over time?

- Reflect on a previous teaching experience where student engagement was lacking. Using the UDL framework, analyze what might have caused the engagement gap and propose concrete strategies or adjustments to overcome these barriers.

- Develop a plan for incorporating ongoing formative feedback into your teaching practice. Outline how you will collect, analyze, and act on this feedback to continually improve accessibility and inclusion in your classroom.