Conclusion: Looking Ahead—Inspiring Ideas for Schools of Tomorrow

Utopias – Where Do We Go from Here? Inspiring Ideas for Schools of Tomorrow

Aga M. Buckley; Georga Dowling; Kerstin Merz-Atalik; and Maryam Mohammadi

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Example Case

“Utopia as an ongoing process that embodies values and visions, rather than merely a final destination” (Maryam Mohammadi, Tehran, Iran)

The example below is a true story of how one family’s vision, with the support and help of their community, created a Participatory School in Tehran, Iran. A concern with Iran’s traditional system is its focus on a singular approach, leaving no room for diverse educational methods. The formation of the Participatory School was an effort to diversify approaches within Iran’s educational system and to make educators and teachers realise that not all students are meant to follow a single method, model, or approach to teaching and learning. Their Participatory school is their inspiring vision toward the creation of a Utopia. The content of the case example is inspired by Dr Nasser Yousefi’s [1]‘Humanistic Education’ book[2], coupled with an educational journey of co-creation of the Participatory School in Teheran. Maryam, an Art Teacher, Executive Director and Advocate for Children, shares her story to inspire thinking of Utopia:

I am proud to discuss our work on Utopia as a representative of the Participatory School founded by Dr. Nasser Yousefi approximately 18 years ago and rooted in a Humanistic Philosophy. A crucial question we must ask ourselves is: where does true education take place, and what constitutes the best educational environment? Most discussions focus on traditional educational centres—schools with specific buildings that adhere to certain standards, adequate lighting, classrooms with tables and chairs, or libraries. These discussions put emphasis on the physical structure of the classroom and the idea that all educational activities occur within the school, minimising the need for external engagement (Yousefi, 2022). In our school, however, we redefine what the school can be. We do not view it as a confined space with walls dominated by systems of control. Instead, we believe that the entire community serves as the school. Every aspect of our community, including museums, parks, sports clubs, shops, and even parents’ workplaces, is considered part of the educational environment. In our philosophy, a school is any place where a child can engage in diverse experiences. The entire local community becomes part of the learning journey, allowing children to learn from real-life contexts. We do not insist on concentrating all urban facilities within the confines of the school; instead, we believe it is essential to cultivate a sense of freedom in students. The resources and spaces within our community are integrated into the educational experience. In a diverse learning environment, children come to understand that not everyone thinks or lives in the same way. This awareness supports the freedom to express individuality while respecting others’ differences. At our school, listening to the voices of others and fostering an environment conducive to dialogue is of utmost importance. We recognise that each child is unique, and education must start from where they are. Considering children’s differences, one of the most rewarding aspects is the intrinsic connection between education and real life. When individuals are provided with opportunities to explore their interests, talents, abilities, self-esteem, empathy, and inner peace, these qualities naturally manifest in their personal and professional lives. Key concepts such as participation, commitment, choice, togetherness, and problem-solving within the life context are fundamental to our educational approach. These principles form the core of our identity, and we consistently integrate them into our curriculum and teaching methods.

Our school represents Utopia, not only for its founder and his family but also for many others. Dr. Yousefi’s personality, vision, and belief in human agency, with unwavering commitment and responsibility for education,have motivated me to continue working within this inspirational educational ethos.

The example from the Participatory School in Tehran (Iran) shows that a school community can follow its dreams and visions, even in the face of contexts not conducive to supporting their enduring educational values. At the selected school, it was initially the fundamental values and expectations of one family who had set themselves the goal of playing a decisive role in shaping the educational biography of their own daughter. This shows the power of individual key figures who, as pioneers, have influenced policy and practice of (inclusive) education worldwide (Boban & Hinz, 2008; Merz-Atalik, 2022). However, the fact that the ‘Participatory School’ exists today and represents these values within its’ educational ethos was only possible because the founder sought allies and fellow campaigners who shared his vision to develop their inclusive approach to education together.

Initial questions

The following questions have guided the chapter.

- What is a utopia?

- What significance do utopias have or could have concerning the transformation and development of educational institutions?

- How can visions (based on utopian designs of a ‘better school and education for tomorrow’) inspire educational transformation?

- What options and methods exist for using Utopias to develop transformative professionalism in teacher and educator training?

- What can we learn from individual schools and peoples’ Utopias to influence change that will have a lasting effect on a school or the education system?

Introduction to Topic

There are many definitions of Utopia. This chapter aims to aid reflection on Utopias and the ‘Schools of Tomorrow.’ It does not intend to give any final definitions nor commit to one theoretical framework. Instead, it invites the reader to embark on a journey of theorising and co-creating Utopia in educational spaces, within learning and teaching, reflecting on past, future and existing educational practice, philosophy and theory. Considering individual values, unique human perspectives and contexts, the chapter starts an exploration of the authors’ belief in inclusive education and, presents the authors’ idea that

There are as many Utopias as there are people in the World.

The word utopia is derived from the Greek où (not) ‘τόπος’ (tópos), translating to non-place. If the word ending is switched to eύ from oύ, the positive, optimistic side becomes visible in a ‘good’ eutopia, making its exceptional power better understood (Hennerfeind et al., 2020). Sir Thomas More first proposed the ideal, imaginary nature of utopia in his 1516 novel written in Latin and titled “De Optimo Republicae Statu deque Nova Insula Utopia”. Sir More’s search for justice led to a Utopian World where everyone’s needs are always met, with little to no hierarchy. His proposed ideal society does not experience a power struggle or greed, keeping morality, fairness and equality at its core. Hennerfeind et al. (2020) reflect on the difference between Thomas More’s historical, already-existing yet distant, perhaps difficult-to-reach Utopian entity (in a satirical sense) versus more current understandings of Utopia. These are explored in this chapter, tentatively suggesting “the positive development of something that does not yet exist (…)”; more so, seeing Utopia as a dynamic “vision of the future” (Hennerfeind et al., 2020: 92).

Utopianism brings mixed emotive responses in people, and there is controversy around its meaning and intention. Considering largely Western societies, Manuel and Manuel (1979) take utopia with Thomas More from the fifteen and sixteen century Renaissance through Rousseau and Kant in the Enlightenment Era. Nineteenth-century utopian socialism leads to Karl Marx and his counter-opposition via Engels or Comte, ending in the not-so-modern (anymore) times of Darwin and, later even Freud. Admired and criticised for not considering distinct disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, economy, or politics, in human societies, Manuel and Manuel’s ‘major utopian constellations’ (1979:13) explore meanings of utopia over time, albeit failing to explain why they existed (Kilminster, 2014). While education undeniably features as a distinct discipline, its evolution cannot be separated from the evolution of human societies and interdisciplinary influence. Hence, considering a wide variety of educational contexts worldwide, against (more current and specific to education) global neoliberal rhetoric that impacts most active attempts of change, utopia as a wordmay feel uncomfortable, archaic or purely naive (Busby, 2015).

Paradoxically, the thought of one person’s Utopia, understood as ideal, becoming another person’s Dystopia seems ever so possible in the reality of 21st-century society. Following the dystopian theme, Bauman (1976), as the ‘sociologist of misery’ (Dawson, 2012: 556), warns about the ‘corrosive nature’ of tomorrow. Still, in his notion of ‘active utopia’ Bauman’s sociology draws a line between the pessimistic and optimistic views of future morality. Focused largely on choice and fate in society least concerned with the morality of human action, Bauman makes historical links to the moral decisions of 20th-century humans, with numerous examples of turmoil, war and unrest, some of which resemble inconsolable differences and continuous conflicts so apparent in the reality of current times worldwide. The chapter’s opening example features a similar schism. Although it introduces what is understood by authors as a ‘realised utopia’ in the form of the existing Participatory School, its social and political context is characterised by a strong divide of opinions and controversy. Despite the powerful impact of religious beliefs impressing political autonomy with directives limiting educational freedom, utopian dreams become a reality and continuously inspire hope and possibility. Jacobsen and Poder (2008: 208) provide a helpful take on the nature of utopian thought:

“Utopianism has remained a continuous and conspicuous yet always ambivalent presence in social and political thought. It has been “praised and castigated, valourised and condemned, worshipped and ridiculed, and yet it has, in some form or other, survived and continued to inspire thinking, dreaming and action throughout most parts of human history.”

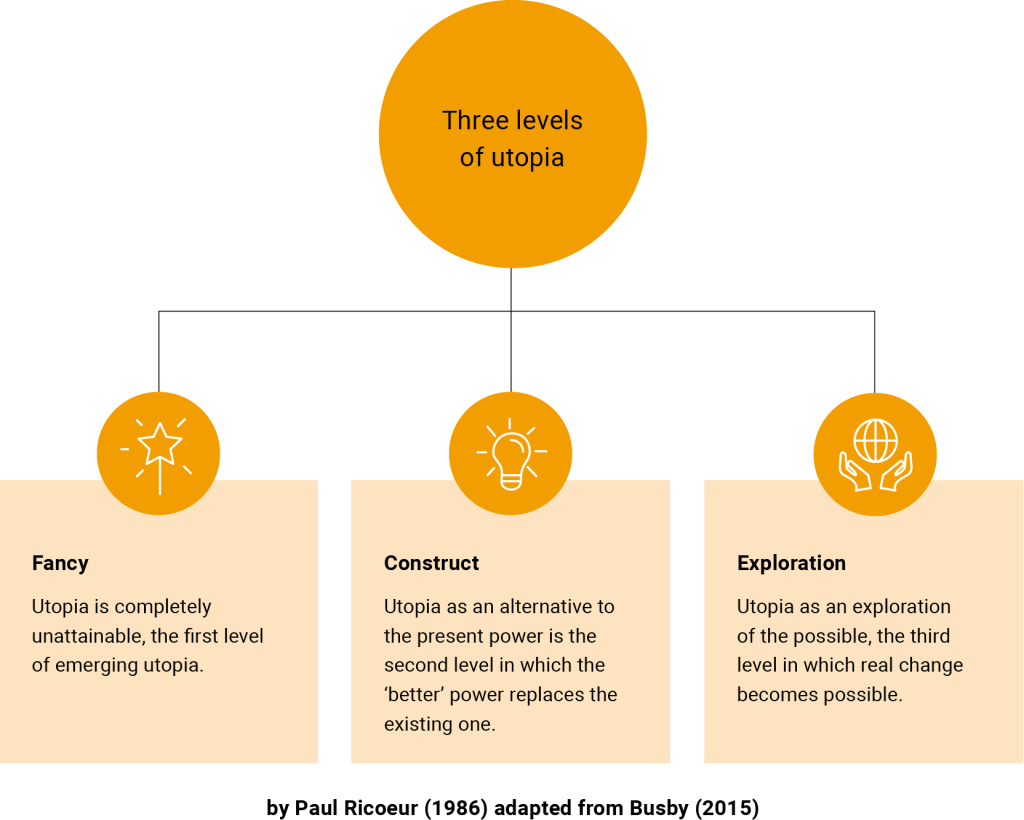

Busby (2015) explores tenets for the ‘pedagogy of utopia’ in her work, drawing on Paul Ricoeur’s thinking that proposes a critical recognition of the current reality, with an immense desire and a possibility to change it, where ‘the utopia is not only a dream, it is a dream that wants to be realised’ (Ricoeur, 1986: 289). There is a strong indication of change transformation in Busby’s account of Ricoeur’s original thought. She further parallels the philosophical tenets of bell hooks’s (2003) Pedagogy of Hope, supported by Henri Giroux (2004), highlighting their dynamic nature and anticipation, a promise of different possibilities (Busby, 2015: 414). Ricoeur (1986) attributes the same possibility to ‘social imagination’, arguing it is responsible for human critical exploration of the status quo (present) to develop an image of an alternative (future). He insists that utopia intends to change or disrupt, proposing three levels, illustrated in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1: Three Levels of Utopia by Paul Ricoeur (1986)

Ricoeur’s notion of Utopia may be formulating an ultimate goal or blueprint, but there is an argument that it can be conceptualised as a method (Levitas, 2013). Instead of an ideal destination, Utopia as a method provides a way to reconceptualise the present for an alternative future (Levitas, 2013; Van Dermijnsbrugge & Chatelier, 2022). Since utopia explores the contexts of human flourishing, the rationale for understanding it as a method provides an opportunity for dedicated, active work through the reconstruction of ‘doing’ and ‘being’ education, critically reflecting and questioning the dominant current status of education and the educational system (Van Dermijnsbrugge & Chatelier, 2022). Moreover, the notion of Utopia as a method can be seen as a crucial element in teacher education, as the concept reflects future teachers’ values and ideas about their ideal school and professionality. Considering how frequently inclusive education is left behind, students in teacher education today may translate it as a Utopian idea, challenging to anchor within the complex reality of everyday school education experiences (based on the contextual environment). It is expected to see inclusive education perspectives conceptualised as illusive, as a never-to-be-reached goal failing against the rigid complexity of educational systems that leave little to no room for inclusion. Störmer (2021:19) discusses this area of tension in his “Inclusion between Utopia and Reality,” suspecting that the concept of inclusion is frequently accompanied by an empty promise or, as some authors prefer to describe an “inclusion lie” or “false magic” moving towards a more dystopian picture. Part 3 of this chapter further explores ‘Utopia as a method’ while considering inclusive education and inclusion as an overarching aim.

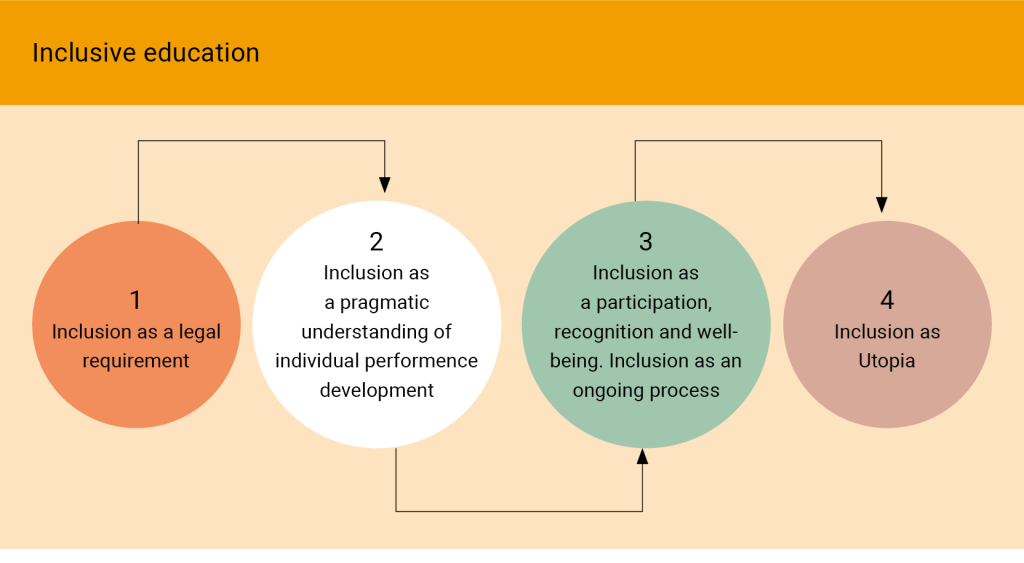

Piezunka et al. (2017: 208) described the postulation of four understandings of inclusive education in schools in German-speaking countries, further illustrated in Figure 2., below. Firstly, the reference to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) places inclusion near the legal footing, showing many countries’ commitment to confront discrimination, with still variable implementation into individual countries’ domestic laws, policies and educational practice. A pragmatic understanding of individual performance development, with a frequent focus on children with Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND), provides a second prism to grasp. Piezunka et al. (2017) further add that each child’s participation, recognition, and well-being are central to performance development and go beyond the performance principle, as inclusion is an ongoing process. The fourth understanding defines inclusion as a Utopia, an ideal of complete inclusion (Piezunka et al., 2017: 213, 216-217).

Figure 2: Four understandings of inclusive education, adapted from Piezunka’s (2017)

Barriers to a Utopian Educational Journey

Many barriers and different beliefs exist within the multiple layers of global educational systems. This causes tensions between different stakeholders and their perspectives, legal and political aspects frequently associated with resources and funding, and the mismatch in the value placed on inclusion, its meaning, and its place in education. While authors acknowledge a vast disparity among approaches to inclusive education worldwide, selected pressures are briefly explored here to encourage reflection on where these overlap with the same relevance globally and consider alternative pathways.

Key aspects

Hidden Politics and Neoliberal Rhetoric

The overwhelming weight of the current neoliberal ideology in education is frequently ‘tangled’ with the politics of funding and resources that fuel its performative culture. Such reality created by the dominant discourse in education makes Ricoeur’s (1986) ‘social imagination’ a vital starting point, inviting the possibility of utopia into the dominant ideology. Reflecting on what it is to be human, recognising one’s values and core beliefs that make us who we are when faced with the reality of now, provides the opportunity to imagine an alternative. Yet, back in the ‘real world,’ neoliberalism is undeniably an embedded feature of modern education. Many argue that its aspects are necessitated by progress, modernity, and growth and that profit-oriented focus is simply a pragmatic approach essential to organisational survival. In the meantime, the social and economic barriers become more visible, with education systems and their educators continuously seeking, integrating and fighting value approaches and principles that directly oppose each other (Ball, 2016).

The idea of the ‘Politics of Education’ is far from new, and any further considerations of methods, models or frameworks proposed in this chapter are likely to be at least inspired, if not well rooted, in Freire’s pedagogical thinking. Well theorised in his ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ (1968), critical pedagogy is undoubtedly a cornerstone of modern educational thought, continuously revisited, critiqued and reinvented throughout the second half of the twentieth century and prevails with much relevance in today’s reality. Freire (1968) understood education as largely political in its shape and form, seeing the banking model of education as a politically necessary way to retain societal power imbalance and oppression. The banking model of education remains visible across higher education institutions, certainly within Western-centric societies. Existing neoliberal ethos sees students as consumers purchasing specific services, where knowledge is expected to be ‘deposited,’ at the price of students’ own independence, skill development and critical thinking ability. Associated with Marxist thinking yet aligned more with radical liberal thought, Freire’s pedagogy seemingly has a less direct focus on inclusive education as it is understood today. Yet, his insistence on the role of education as “the practice of freedom” (Freire, 1968:62) and a vehicle to raise the critical consciousness of all learners through problem-posing education feeds directly into the modern vision of inclusive teaching and learning. Freire’s belief in the creative power of dialogue, underpinned by a profound love for the world and the people in it, remains a recurrent theme in negotiations of inclusion.

Despite all the reforms, interventions and proclamations for inclusive education, most school systems internationally do not change (significantly) (Kruschel & Merz-Atalik, 2022: 2). There are manifold reasons attributed to this, and three aspects are selected to explore their systemic nature. They can be seen as barriers to utopian thinking as well as barriers to the implementation of utopian visions. 1) the loose coupling of the systems; 2) the recontextualisation by the actors; and 3) the path dependency of developments (ibid.). The education system comprises many loosely coupled systems, institutions and organisations. Changes and reforms need to be considered in terms of their concrete effects on all the different levels and parts of the system. Therefore, it seems crucial that all actors actively participate in constructing the vision behind the process and the process itself. Path dependencies exist; all actors have contributed and invested in the system. The causes of these phenomena are to be found in historical developments and settings with which paths have been taken in the education system in terms of norms, structures, or cultures. These paths have led to firmly anchored rituals of action and arrangements at all levels of the system, which can now only be abandoned with great effort and solid impulses for change (Kruschel & Merz-Atalik, 2022). Institutional arrangements and institutionalised activities are complicated to change (Blanck et al., 2013: 270) in the long run. Government policies define education and offer guidance and support, but they can also constrain it. Some government policies are used to ‘measure’ the benefits of education (Goodson, 2003). Walsh (2006) claims that this measurement of performance has led to critical voices not being heard at policy level. Tensions further arise when the school’s ethos does not marry with the political agenda of government policies (Hayes, 2013).

Culture, Ethos and Professional Identity

Further pressures arise when teachers realise that the school’s ethos is not aligned with their individual, professional ethos (Hayes, 2024). Creating spaces where the teachers can grow, feel valued, connected, and empowered is imperative (Hagenah et al., 2022). The development of professional learning communities allows like-minded educators to follow their Utopian thinking by sharing experiences, collaborating, and offering solutions that further benefit the students in the classrooms. There is an acknowledged tension between the initial idealism or Utopias of new teachers embarking on their careers, and the realities experienced teachers face (Buxarrais, 2021). The development of teachers’ professional identities can get lost in the current testing and results-driven climate that has engulfed education (Furnera and McCulla, 2019). The bureaucratic nature of box-ticking and exam readiness has led to a focus on outcomes instead of learning, somewhat reminiscent of Freire’s (1968) concern with the nature of the banking model of education and, more importantly, its purpose. As ethos within schools succumbs to this global neoliberal trend, the value system, by default, alters.

The ethos of a school is defined as “those values and beliefs that the school officially supports” (Donnelly, 2002: 34). Therefore, as the school supports a value, it becomes ingrained into the school’s culture. Tensions arise when the ethos in the school does not marry with the political agenda of government policies (Hayes, 2013) or other ideological differences, as illustrated in the chapter’s example. This leads to a lack of educator agency (Robinson, 2012) with a primary focus on the constraints of paperwork related to complying with policies. The level of administrative burden increases as the system becomes more outcome-focused, leaving teachers burnt out and questioning their professional identities. The disparity between the ‘ideal’ and the ‘reality’ continues to widen when the ethos and culture of the educational institution are at odds with the teacher’s ethos (Robinson, 2012), leaving a limited scope for Utopian thinking. Such tensions break down the foundation of professional identities and moving forward to create a shared vision becomes harder to realise.

Following the case example earlier in the chapter, its second part expands on the importance of culture, ethos and teachers’ professional identity.

Example 2

According to the example of the Participatory School, it is essential to highlight that diversity in the educational environment makes a significant contribution and can play a crucial role in overcoming obstacles. In this system, there is a strong belief that diversity is critical in cultivating a vibrant and dynamic society.Embracing diverse perspectives and experiences fosters a culture of creativity and innovation.Individuals exposed to and accepting of diversity are more likely to develop enhanced creative thinking skills. Furthermore, diversity is instrumental in promoting peace by encouraging understanding and acceptance of different lifestyles, beliefs, and values. Recognising and respecting these differences is essential for nurturing harmonious coexistence. Embracing diversity enriches human relationships by fostering communication and mutual understanding, encouraging individuals to make deliberate efforts to understand one another and thereby strengthening social bonds. This educational model posits that classroom diversity enhances the learning experience for all students. By fostering an inclusive environment where differences are celebrated, and every student is given equal opportunities to participate, inclusive education promotes social cohesion and eliminates barriers to learning.

On the other hand, a critical factor in overcoming obstacles and tensions in the educational path through a humanistic approach is the participation of families in educational programs. We advocate for involvement in social programs that include travel, exploration, scientific inquiry, and knowledge creation. Educational programs should be culturally, socially, and environmentally aligned, ensuring they resonate with and enrich everyday life. Sustainable education thrives when it originates and evolves in harmony with life, shaping and being shaped by its continuous processes. Understanding the audience’s perspectives on human life, existence, and education is essential. Life and education are interconnected and filled with challenges, doubts, contradictions, and complexities. Emphasising interdisciplinary perspectives enriches the educational dialogue. The active involvement of families in educational programs helps integrate life-centred ideas into educational practices.

Another important and noteworthy point is that dreaming and a sense of wonder through ideas and imagination can be seen as forbidden or hindering factors in traditional educational paths. In conventional educational systems, children are often asked to follow a specific, linear path. However, we must recognise that this rigidity can be one of the obstacles to creating a utopia. This is where the humanistic approach fosters a sense of wonder and encourages students to approach every phenomenon with curiosity and exploration. Certainty can inhibit curiosity and limit students’ ability to perceive the world as a realm of possibilities. By nurturing curiosity and wonder, students are motivated to engage in discovery, creation, and experiences that continuously shape and evolve their understanding of reality through social interactions and life experiences. The goal is to develop an educational system that produces knowledgeable students and cultivates wise, capable, and compassionate individuals who are prepared to impact the future positively. Achieving this vision requires substantial changes in mindset, curriculum, teaching methods, and school culture. Nonetheless, this vision is worth pursuing, as it inspires and motivates both educators and students. In this educational context, there is a belief that personal dreams are crucial and significantly contribute to individuals’ learning and academic processes. The school and the school community provide opportunities for everyone to pursue their dreams to the fullest extent possible.

As a private institution, we operate independently of government approval, which sets us apart from the traditional educational system. Our school serves approximately 240 students, both boys and girls aged 6 to 18, a practice that diverges from the prevailing educational norms in our country. To further support our students and advance our educational objectives, we recently established a new branch of the school in Toronto, Canada, called “The Peace School.” This branch is a member of several international organisations, including the European Democratic Education Community, the Alternative Education Resource Organisation, and Humanist Kids (You can find out more about Toronto Peace School in the International Schools chapter).

Utopias as a method: Impact on transformative actions

Creating a Vision

Hennerfeind et al. (2020: 94) consider vision as more tangible than utopia, pointing out its limited reach over truly transferable change aspired for:

“Although the word is also used to describe something that has not yet happened, it is visible from afar. It is more likely to concede the possibility of coming true than utopia. It is closer to events and more comprehensible. What makes it possibly inferior to utopia is its reach. Due to its closer perception, it seems to be associated with less risk. This makes it more attractive in fast-moving times. So, when it comes to quick, short-term changes, people tend to think of visions rather than utopias. However, if far-reaching and sustainable change is required, the vision would be too short-sighted.”

The starting point for any change is a critical reflection on educational practices, their history, and the evolution of differential approaches and understandings of education and its purpose, role and meaning for learners (that includes teachers). Here again, Freire’s (1968) concept of critical consciousness relates to the development of the learner’s critical, questioning mindset, more importantly, however, the necessity to revisit educators’ own ‘conscientizacao’ (Freire, 1968: 55). Problem-posing education invites learners to consider their relationship with the world around them and transformative role of dialogue, enables educators learning, from and with the students they teach. Education becomes a transformative process, anchored in the learner’s reality, where education cannot take place unless all actively participate.

“True dialogue cannot exist unless the dialoguers engage in critical thinking -thinking which perceives reality as a process, as transformation, rather than as a static entity-thinking which does not separate itself from action, but constantly immerses itself in temporality without fear of the risks involved. (…) For the critic, the important thing is the continuing transformation of reality.” (Freire, 1973: 92)

This inquiry then leads to consultation with and consideration of all parties to reimagine alternative tomorrows, with a critical pedagogic lens inviting (if not challenging) student teachers to think critically about their practice and learning. Values, biases, and opinions of all participants are considered, and more importantly, how they are considered matters. Biesta’s (2012; 2013) framework for public education suggests three lenses: ‘for the public’, ‘of the public’, and ‘in the interests of the public’ (Biesta 2012; 2013). Education ‘for the public’ is an education aimed at the public, where the public is instructed on how to think and act. This erases plurality and ensures that all learners are equal. Education systems are assumed to know what is best for the public and will teach it to them (O’Toole, Dowling and McElheron, 2023). Education ‘of the public’ emphasises learning rather than instruction, moving towards a system based on citizenship, emancipation, and visibility. Consultation and incorporating the voices of educators, children, parents, and communities into pedagogy, policy, and planning are carried out. However, Biesta (2013) argues there is a flaw within this viewpoint that ‘everyone’s voice is equal’; some voices may not be fair or inclusive. ‘In the interest of the public’ allows us to question which voices are helpful to living together in unison and which are hindering (O’Toole et al., 2023). Using Biesta’s framework with national and international diversity, equality, and inclusion charters (UNCRC, 1989; UNESCO, 1994) supports the inclusivity of voices through an inclusive lens. O’Toole et al. (2023) argue that consultation is insufficient to ensure a fair and equitable narrative becomes visible. Instead, the ‘consideration’ of all parties should be reviewed. They further argue that these considerations are not discrete and must be understood in dynamic synergy. There are, of course, often tensions between different perspectives. Negotiating these tensions is part of a democratic society (O’Toole et al., 2023).

To ‘consider’ all parties, their voices must be accessed, heard and used to enact change. Lundy’s Model of Participation (2007) can be used to access students’ voices. This model conceptualises Article 12 of the UNCRC, which states, “I have the right to be listened to and taken seriously” (UNCRC, 1989) through the lens of accessing children’s voices. Lundy’s model (2007) requires four elements: Space, Voice, Audience and Influence. Space for children/students to feel safe to voice their opinions is essential to ensure meaningful engagement. Children and young people will express their voices in spaces where they feel safe and where the relationship is caring and nurturing. Creating a trusting and healthy relationship prior to utilising techniques to access voices will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. It is imperative to ensure the children/students have an audience that includes people who would and could take them seriously and support getting their opinions brought to decision-makers. The children/students should be seen as co-decision makers where appropriate. The final element is influence. This is where the children/student’s voice and opinions influence practice. Therefore, practices are altered to consider the views of children, students, and young people.

Creating a space to explore and co-create utopias for inspirational, inclusive practices of tomorrow

Koenig et al. (2022) speak of a teaching dilemma in teacher education – we are teaching for an inclusive education system that does not widely exist today. Even if a highly inclusive aspiration has been developed during studies or training, it is often almost impossible to put it into practice in insufficiently inclusive organisations in education today. Nick Peim has restated recently that “education has not been delivering on equality: inequality is precisely what it is for!” (Peim, 2023: 2).

Peim has long argued that it is the socially disadvantaged who are particularly ill-served by the so-called ‘gift that keeps on giving’. For many people, the offer they cannot refuse is often one they are not in a position to accept, partly because this is someone else’s aspiration. Although there are obvious parallels to Freire’s (1968) work in Peim’s account, bell hooks (1994) was more explicit in highlighting the point about meaningful sharing of education relevant to creating the space to explore and co-create. Her work was much inspired by Freire’s insistence on common, mutual human growth, with privileged and less privileged influencing each other to transform. Seeing ‘education as the practice of freedom’, bell hooks understood the flaws of education systems in their frequent omission of learners’ social reality (class, gender, sex, racialised positionalities and relevant experiences). Thanks to Freire, education opened up a possibility ‘to move beyond boundaries, to transgress,’ making a true, authentic difference in the world (hooks, 1994:207). This raises the question of educators’ understanding of the role they play in the dynamic nature of learning and teaching, seeking to transform their own practice and thinking, continuously learning from each other as much as their students.

“Inclusion [presupposes] a change of pattern […] – understood as an intentional process of turning away from a mode of optimising, which in a way would only mean a further affirmation of the status quo. Instead, a transformative understanding of inclusion requires actors (in organisations) to be both aware of the way current structures have become and to intentionally shape an active process of ‘future-forming’ (Gergen, 2015) and reflexive future work” (Koenig et al. 2022: 22).

Sharpe et al. (2016) consider that people can develop forms of future consciousness and, thus, of changing patterns. Teachers and all other participants of education systems should be empowered to continuously and proactively develop approaches, knowledge and skills that make it more likely for them to be able to:

- Orient themselves in the permanent – neither foreseeable nor linear – transformation process towards a more inclusive education system, in the sense of the vision in a self-reflective, networked and more targeted manner.

- Meet the challenges associated with the recognition of human diversity and diverse educational pathways in organisations and institutions with diversity-sensitive and inclusion-oriented attitudes and practices.

- Position themselves as a transformative actor for more equality and educational justice in the constantly changing education system and be able to simultaneously remove barriers to participation and learning for all (Booth & Ainscow 2017).

- Develop a willingness to further professionalise themselves by the changing demands posed by the diversity of learners and the living conditions in our society within the framework of their professional biography (Merz-Atalik, 2024).

Danforth (2017) says successful inclusive educators are characterised by a unique approach:

“They do not ignore the gap between their ethical beliefs and their daily work in schools. They intentionally toil in the gap. They enter into that uncomfortable space, explore their commitments and behaviour, and figure out how to better enact their most cherished ideals” (Danforth, 2017: 8).

Epistemic knowledge alone cannot facilitate the levels of change needed to address contemporary societal challenges, and according to Sharpe et al. (2016), other forms of practical knowledge are required. The adaptation options for the potentially adaptive human system can be based on the past and the future. Sharpe et al. (2016) claim that without such “reframings”, it is practically impossible to reconcile the “objective” world out there with people’s subjective perceptions of the future. Sustainable solutions are not only related to political will and action.

They “also require a collective ability to co-create and convene spaces for genuine transdisciplinary co-operation and participation across the full spectrum of human diversity and difference in order to address the question “what type of society [do] we want to live [in] and who [is] the ‘we’ […] answer[ing] that question (Abbott et al., 2017: 815)” (Koenig et al., 2022: 127; highlighted by the authors).

Utopias cannot be traced back to previous experiences from the past, either from the perspective of the individual or the system, as there is still no (organisational) memory for such experiences (Koenig & Strasser, 2022), for example, with inclusive education. Therefore, when embarking on co-creating Utopia, the authors want to bring people together to go on a journey that will be characterised as a collective intelligence creation process. Two critical points must be present for an authentic and meaningful shared vision to be created: it must be possible to reach all people and levels of the system (Whole-System-Approach), and all individuals involved must be able to contribute to the change (participation in the process). Koenig et al. (2018: 34) consider that “the potential for transformation lies in the flexibility to think about the future beyond the continuation of the past.”

When revisiting Ricoeur’s (1986) levels of utopia within classrooms, coupled with a whole system approach where all individuals can participate, the created space allows positive relationships to flourish (Lundy, 2007). Positive relationships are integral to children’s and young people’s education (Ebbeck & Yim, 2009). Supportive and warm interactions throughout the classroom, teacher and student, and peer interactions lead to a productive learning environment (Wubbles et al., 2012). When all opinions of the children, students, parents and educators/teachers are sought, the commonalities can be reviewed, and a shared vision can be created. This shared vision becomes how the classroom looks and feels.

Defining shared value

Considering value systems starts with a reflection of personal values. These values are individual to each person and frequently relate to how people construct their identities. Intrinsically, each person ‘knows’ what matters most to them…or at least they think they know until they are confronted with questions, situations or circumstances that challenge these deeply integrated ideals and are forced to reconstruct, change, or transform their thinking. This begins with a personal journey of discovery where each person uncovers which values are important to them. Deconstructing these personal assumptions and biases is an integral element of understanding one’s own personal value system (Brookfield, 1995).

Creating a space where students can discuss their values and co-create shared values allows essential questions to be answered. Establishing the importance of individual and personal values and how they may interact with the educational context supports the ability to reconcile, at times problematic, alignment of personal and professional lenses. A deeper level of reflection may support further understanding of how these individual values may be translated into inclusive educational practice.

Referring back to the authors’ starting proposal that there are as many Utopias asthere are People in the Worldhighlights that every person’s vision of their Utopia is different. Therefore, reflection on understanding one’s own values before inviting other people’s perspectives and values is necessary. Linking individual utopias within a group to create a shared vision often engages working with deeply personal values to co-create a space where Utopian visions can be realised. Common values associated with educational systems are community, democracy, love, relationships, uniqueness, play, identity and belonging, compassion, equity, empathy, advocacy, passion, agency, and autonomy. These shared values within a classroom can lead to the overall values of the school. Creating a cohesive vision from learners and educators and the wider community to principals and boards of management and leaders shows how these shared values can bring about considerable change.

Example 3

“Based on the values mentioned above, the vision for future education in a participatory school focuses on areas that benefit everyone, especially children, as outlined below.”

In this way, there is a desire that we plan in detail how to support an educational environment, especially for the benefit of children and adolescents, and it helps us move forward to co-create a path for the creation of children’s/student’s utopia.

One significant focus is on young children, particularly those up to two years of age. We aim to develop resources to identify their needs and create diverse experiences from birth to two years old. This involves organising continuous training courses for educators of young children, enabling them to address essential topics and shift their perspectives on child development and education. These programs are designed to be child friendly. We are also working to establish connections between organisations involved in child development, including government and non-governmental organisations, charities, schools, the private sector, and individuals interested in enhancing children’s lives. This initiative aims to create a collaborative network that promotes the well-being of children and fosters a cooperative environment among various stakeholders. Another goal is to emphasise diversity in educational approaches, encouraging families to advocate for schools to incorporate children’s voices and opinions into educational programs. Enhancing children’s health, safety, and care is another goal, particularly addressing the high incidence of accidents, from natural disasters to road and traffic accidents. There is a lack of official co-operation and commitment to developing child-friendly, safe urban environments. Despite our efforts in this area, progress has been limited, and we remain hopeful for future advancements in ensuring children’s health, safety, and care. In addition, promoting environmental sustainability is a priority. We advocate for planting trees and developing forests, leveraging the extensive potential of children and their families nationwide to contribute to forestry efforts. Another initiative we are considering is the prevention of malnutrition among children. This project aims to engage governmental and non-governmental organisations to determine their role in addressing this issue.

Supporting the family unit is also a crucial objective. While the definition of family forms may evolve, the core principles of co-operation, love, empathy, and care remain fundamental. We aim to promote and strengthen these principles within society. To this end, a Family Education Working Group was established years ago to conduct regular meetings, focusing on improving knowledge and awareness through group readings and critical thinking. Finally, we seek to deepen our understanding of the culture, art, and heritage of our land. This involves introducing teachers, coaches, families, and children to the cultural background of our region, fostering a greater appreciation and connection to their cultural roots. Understanding and promoting a culture of peace among children through Augmented Reality (AR) can be a significant objective of future educational programs. Teaching children to listen to and accept others is crucial for fostering an environment where peace, equality, and diversity coexist. Additionally, there is a critical need to focus on support and educational programs for children with special needs. This encompasses all children requiring special care, whether in the short or long term, including those in crisis, children from rural areas, immigrant children, minorities, and other vulnerable groups.

In alignment with the goals above, our efforts aim to broaden the educational horizons of children and teenagers. We assist them in moving toward their utopias, encouraging them to envision and articulate their dreams. Through workshops and programs, we foster collective dreaming, empowering them to travel fearlessly toward the utopian future that represents our aspirations today.

Models and methods of reflection

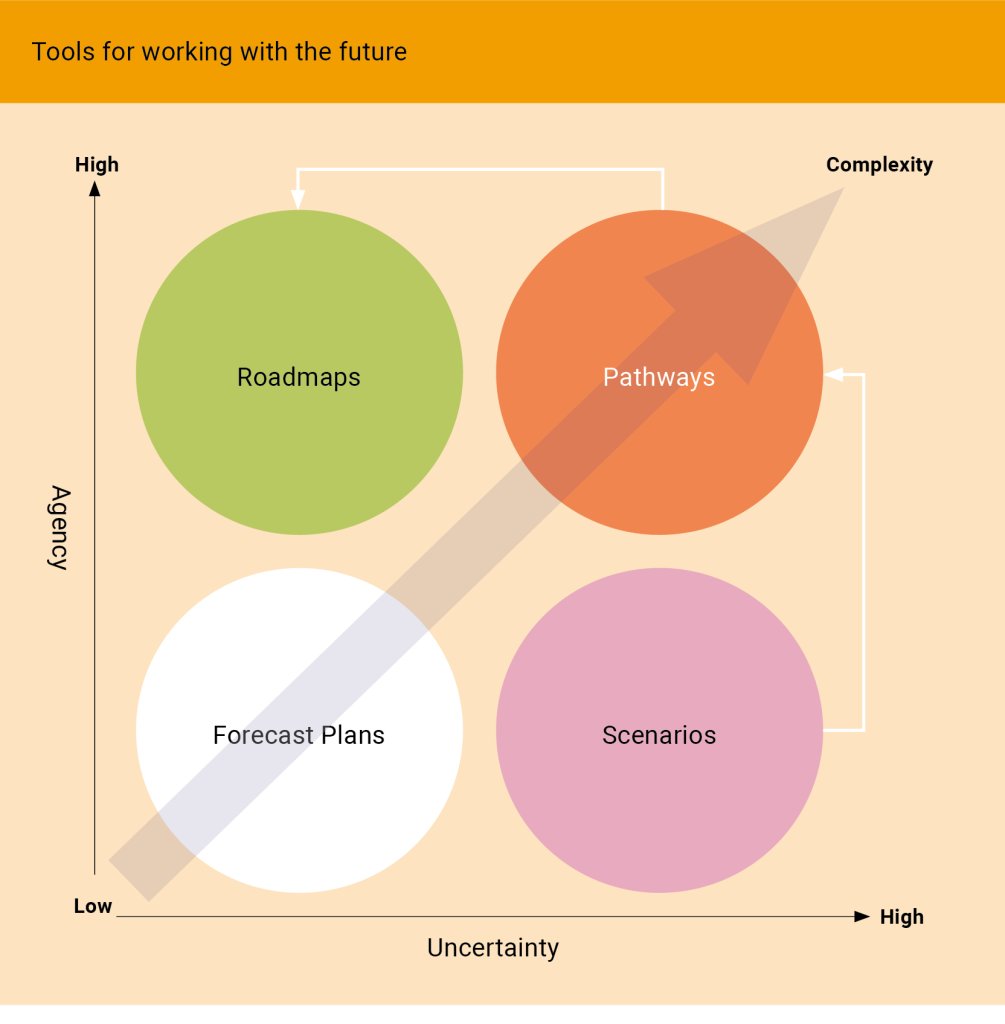

If we define Utopia “as a defining property of any educational experience that wishes to retain a genuinely contestatory power” (Lyotard, 1993; Readings, 1995), utopias could thus not be an anticipation in any ‘natural’ or logical sense. We can use different methods and follow different concepts or starting points to anticipate an ideal future. There are various tools for working with the future, so we would first like to stress some fundamental frameworks.

Figure 3: Tools for working with the future adapted from Sharpe et al. (2016)

Some tools for working with the future tend to focus on a clear goal (like a final destination or status), which brings a lower capacity of uncertainty, as the goal is clearly defined and shared in the contextual environment of the change process. For example, to just add new aspects into the curricula instead of changing its basic structures and values. In other change processes, like inclusive school reforms in the whole education system, we find a relatively high demand for agency and feelings of uncertainty because the reform itself is complex and has to include many different levels of the system, stakeholders and agents. The number of players involved in the transformation processes is almost unmanageable. Pathways approaches attempt to deal with complexity and raising agency, for example, PATH (Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope). The method has been developed as a strengths-based, person-centred planning process by John O’Brien, Marsha Forrest and Jack Pierpoint. The PATH process is designed to help a focused person establish their own vision for their life and imagine what support and connections will help them achieve this vision. PATH is also intended to be a community-building opportunity and is not limited to systems. Therefore, it focuses on an individual and their personal tomorrows and dreams. The process starts with creating a picture of the future (the North Star) and then going backwards, what should be developed three months before, six months before, and so on.

“Don’t be afraid of utopia and vision if you are not trapped in them; they are both helpful, strategic tools without which there would have been no significant further development of humanity” (Hennerfeind et al., 2020: 95).

Brookfield’s model of critical reflection:

Through critical reflection, a sense of one’s value system, beliefs, and assumptions are interrogated. Brookfield refers to these as “hunting assumptions” (Brookfield, 2021: 7). He argues that understanding one’s assumptions is highly challenging and often resisted. Further contesting that “assumptions frame our thinking and determine our actions” (Brookfield, 2021: 1). He reviews three types of assumptions: paradigmatic, prescriptive and causal assumptions:

Paradigmatic Assumptions: These assumptions are the hardest of all to uncover, and, when critically reviewed, they are the ones that have the most significant impact on our lives. These worldview assumptions relate to how we see and order the world. They are fundamental to how we live our lives, which is why they are so hard to uncover. An example of a paradigmatic assumption could be that children are independent learners who learn through taking risks and exploring their environment.

Prescriptive Assumptions: These are what we think should happen in different situations. These are grounded in our paradigmatic assumptions but are more accessible to uncover. To follow the paradigmatic assumption mentioned earlier, a prescriptive assumption could be that educators/teachers should provide challenging environments for children to show their independence and encourage them to take risks.

Causal Assumptions: These assumptions are the easiest to uncover and understand. They are assumptions about how things work and about the conditions under which these can be changed and how we can impact those processes. Our causal assumptions are also grounded in our paradigmatic and prescriptive assumptions. Following on from the paradigmatic and prescriptive assumption given above, a causal assumption could be: That children should take risks, although these risks may cause a minor injury, because this encourages their independence and understanding of the world around them. Throughout our lives we are making causal assumptions, be them conditional or retroactive (historical). If the assumption is conditional, then we assume that if we do one thing another will happen. If the assumption is retroactive, it means that we are assuming this because historically this is what happens (Brookfield, 2021). By unpacking these assumptions, we create opportunities and a willingness to understand them, which in turn creates an understanding of our value system and allows for critical reflection.

Embarking on a Utopian Journey

“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men and women to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea” (Saint-Exupéry, 1943).

The following framework is an easy-to-follow guide, where the elements are grounded in research that allows individuality for each group to establish their utopian journey. This is supposed to be a framework that utilises Understanding, Transformation, Opportunities, Perspectives, Inclusion and Advocacy.

A framework to support a Utopian journey

Figure 4: Framework to support a Utopian Journey in education.

U – ‘Understanding’: At the beginning of the journey, it should be ensured that mutual ‘understanding’ is recognised as an essential starting condition for the joint reflection process by all actors involved. The attitude and the activities should always be geared towards identifying the individual perspectives and histories of all persons and groups involved. To this end, guiding principles should be developed and recognised for the methodological approach, interactions and communication. Mutual understanding and trust are fundamental prerequisites for beginning to design and create shared visions for a school of the future. These ‘understandings’ involve building relationships within the group that are based on mutual trust and respect.

T – ‘Transformation’: Transformation is critical to embark on a journey to co-create utopia. Visions are the driving force behind “Transformations” in the sense of complex changes (for example, from a social norm-oriented, ableist to a subject-oriented, appreciative pedagogy) instead of purely adaptive changes. The willingness to change and transform a system to reflect the needs and desires of the group is essential. If there is no willingness to change, then alternatives for tomorrow will never be realised. This element involves deep reflection and transformation of practices and principles; therefore, the willingness and desire to change are essential.

O – ‘Opportunities’: Creating opportunities to ensure all actors feel safe and willing to participate, unpack, and share their opinions is an integral part of this framework. Fostering nurturing relationships and creating a safe and inclusive environment for the school community to openly and honestly feel they can share their opinions about what should change is challenging to achieve. Integrity, openness and a willingness to take on board people’s views to change shows professional integrity, but it also takes courage and strength. This is easier to achieve in a learning community with like-minded professionals but can be developed in any group or constellation with the right considerations.

P – ‘Perspectives’: The perspectives of all actors must be unpacked and understood as all perspectives are critical to hear to gain a deep understanding of other people’s value systems. However, not all perspectives are helpful, as discussed earlier in this chapter when reviewing Biesta’s framework (2012). Ensuring that all perspectives taken onboard are embedded in inclusive strategies and inclusive policies nationally and internationally is crucial. This provides the foundation of a shared vision with the integral elements of rights, inclusion, agency, and equality.

I – ‘Inclusion’: Inclusion of all those involved in the educational process is integral to the journey. Deciding who is involved and ensuring that all are included is imperative. This network of actors who should be included in the transformation process of the education system are families, children, students and other social caregivers; this consists of all school specialists, teachers and other people involved in the management and organisation of the education system. Inclusion is a ‘transformative task for the future’ (Koenig et al, 2022). Inclusion is the path, the process and the goal. Inclusive education systems need transformative professional self-images or identities from the professions involved (Merz-Atalik, 2024). Utilising methods to ensure the inclusion of everyone consists of reflecting on how to access all voices of the actors involved. Ensuring inclusion involves embedding practice in inclusive, reflective practices that support all actors involved.

A – ‘Advocacy’: This is an essential element involving much thought and reflection. Discovering what you advocate for involves deeply understanding your views, opinions, and biases. Using Brookfield’s model to uncover personal assumptions supports unpacking one’s value system and allows one to realise who and what one advocates for (Brookfield, 2021). Ensuring there are shared values is an integral element of the utopian journey for all actors involved.

An example of creating a shared vision and values towards a utopian approach in a classroom

“For any group of people to get an education of their own, the first need is to have a say and be listened to” (Griffiths, 2003: 34).

The following is an example from a Child Care Centre:

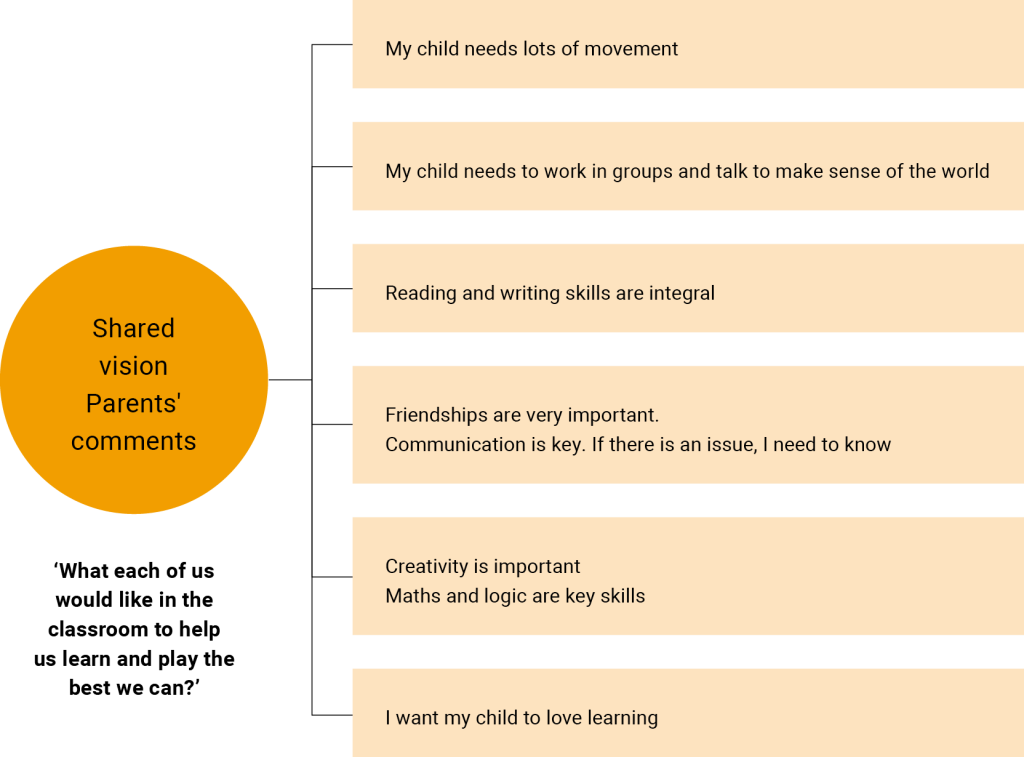

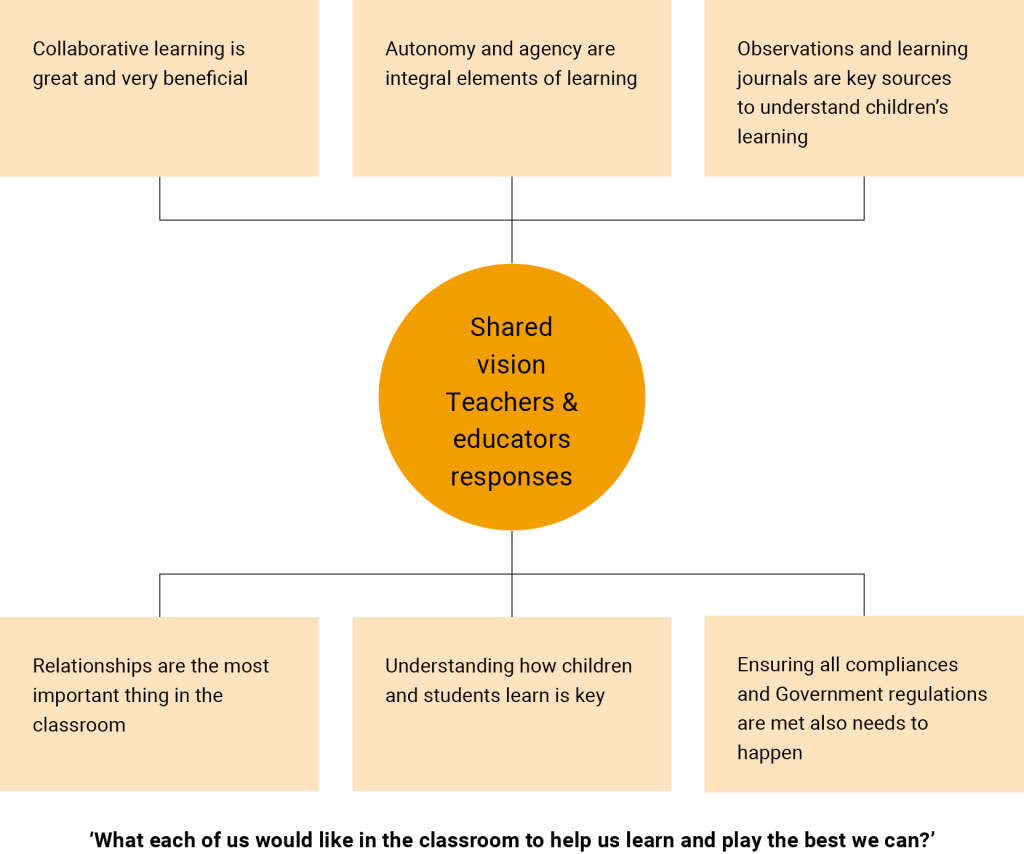

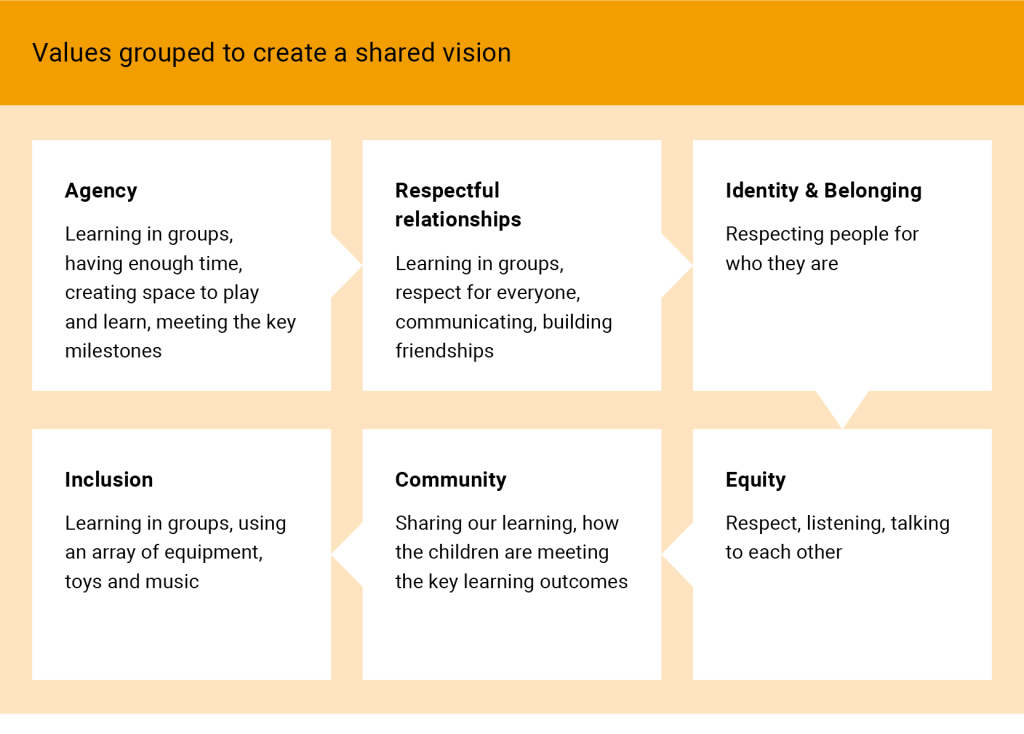

I would like to share some experiences from my work as a leader of two early childhood settings regarding using shared visioning methods to transform the educational environment and programme of our children, their parents, and our educators. Creating a shared vision and discussing our utopias was recently carried out in a class of mine with children aged 4 to 6 years. We began by talking about ‘What each of us would like in the classroom to help us learn and play to the best we can.’ Pseudo names are used throughout this example; the main comments from the children are shown in Figure 5. The parents’ responses are illustrated in Figure 6, and the teacher’s and educator’s responses are illustrated in Figure 7 below.

Figure 5: Shared Vision Example from Child Care Centre, Children’s Comments

Figure 6: Shared Vision Example from the Child Care Centre, Parents’ Comments

Figure 7: Shared Vision Example from the Child Care Centre, Teachers and Educators responses

Thematic analysis was used to ensure all contributions were captured effectively and the nuances of their answers understood (Hejil and Petersen, 2024). These elements were then grouped to form our values and our shared vision that led to collaborative agreement illustrated in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8: Shared Vision Example from the Child Care Centre

Figure 9: Child Care Centre, Classroom Agreement

In our classroom, we agreed:

When I reflected on my practice, I found that there were areas I needed to alter.

I reviewed how I could support the class to ensure I facilitated and created a space where they could best learn. The review of practice led to more project-based work with added time and flexibility, a universal design for teaching, and a review of the spaces we could utilise within the building and the community. I also reviewed how we could involve the community in sharing our learning, focusing on innovative ways to communicate our knowledge to others.

This scenario showed how a teacher/educator used the UTOPIA framework above within her classroom. Mutual ‘understanding’ was recognised as an essential starting point for the joint reflection process in this scenario. This ‘transformative’ approach by engaging in critical reflection took place through fostering positive relationships and creating ‘opportunities’ to gather information involves ensuring the environment is based on trust, respect and inclusion. This created an avenue to ensure that honest ‘perspectives’ were gathered that reflected the actual thoughts and feelings of the people involved. This ensured the ‘inclusion’ of all and the integrity of inclusive charters and policies visible within the ideas. An insight into what all the actors were ‘advocating’ for appeared, and a shared vision of alternative realities emerged. This example shows how teachers can quickly gather perspectives to create a vision and allow everyone to go on a utopian journey to better their learning.

Conclusion

The Participatory School in Tehran (Iran) example shows that a school community can follow its dreams and visions, even in conditions and contexts that may not be conducive or supportive. At the selected school, it was initially the fundamental values and expectations of one family who had set themselves the goal of playing a decisive role in shaping the educational biography of their daughter. This shows the power of individuals is key worldwide (Boban & Hinz, 2008; Merz-Atalik, 2022). The Participatory School (Teheran) exists today, representing these values in its educational approaches because it co-created a more powerful collective voice that made the dream a reality, like many other schools internationally that went on a Utopian Journey.

Reflecting on one of the opening concepts, ‘There are as many Utopias as there are people in the world,’ reinforces that utopia is different for everyone. This chapter highlights that it is not an elusive dream that cannot be achieved. Instead, it is a method and a journey that you, as a teacher, can choose to embark on with your students (on every level of education, including places of adult- or teacher-education). Beginning with conversations about what Utopia is to them and concretising that abstract into creating an environment in which they can see, hear, and feel. Defining shared values and creating shared goals allows these illusionary ideas to become an authentic environment where meaningful teaching and learning can occur. Then, the creation of alternative tomorrows becomes a reality.

Local contexts

The local contexts were contributed by authors from the respective countries and do not necessarily reflect the views of the chapter’s authors.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.

Interactive elements such as videos, podcasts, and expandable text boxes have been removed from this print version.To access the full interactive content, please scan the QR code to view the online version of this chapter.

Closing questions to discuss or tasks

- When creating a shared vision, who’s voice would you access?

- How would you access these voices?

- What models would you use to reflect on your practice?

- How would you try to understand your students’ UTOPIAS?

- Has the ethos and culture of your educational facility altered your professional identity?

- How would you bring your students on their utopian journey?